Abstract

Background

The hepatitis E virus (HEV) has a global distribution and is known to have caused large waterborne epidemics of icteric hepatitis. Transmission is generally via the fecal-oral route. Some reports have suggested parenteral transmission of HEV. Anti-HEV prevalence data among chronic hemodialysis (HD) patients are few and give conflicting results.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in August of 2004. We tested 324 chronic HD patients attending three different units in the city of Tabriz, northwestern part of Iran, for anti-HEV antibody. A specific solid- phase enzyme-linked immunoassay (Diapro, Italy) was used.

Results

The overall seroprevalence of hepatitis E was 7.4 %(95% CI: 4.6%–10.6%). The prevalence rate of HBV and HCV infection were 4.6% (95% CI: 2.3%–6.9%) and 20.4% (95% CI: 16%–24.8%), respectively. No significant association was found between anti-HEV positivity and age, sex, duration of hemodialysis, positivity for hepatitis B or C virus infection markers and history of transfusion.

Conclusion

We observed high anti-HEV antibody prevalence; there was no association between HEV and blood borne infections (HBV, HCV, and HIV) in our HD patients. This is the first report concerning seroepidemiology of HEV infection in a large group of chronic HD individuals in Iran.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The causative agent of hepatitis E, hepatitis E virus (HEV) had provisionally been classified into the caliciviridae family, but in the most recent ICTV (International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses) classification, HEV has been placed in its own taxonomic group within the class IV (+) sense RNA viruses, "Hepatitis E-like viruses" [1, 2].

Hepatitis E is an important public health concern in many developing countries of Southeast and Central Asia, the Middle East, northern and western parts of Africa, and Mexico, where the occurrence of outbreaks have been reported [3–7]. Although the overall mortality rate associated with HEV infection is low, it is reportedly as high as 20% in infected pregnant women [8, 9].

Transmission of HEV occurs primarily by the fecal-oral route through contaminated water supplies in developing countries. Recent studies have indicated that zoonosis is involved in the transmission of HEV, especially in industrialized countries where hepatitis E had been believed to be non-endemic [10, 11]. Further, vertical transmission of HEV from infected mothers to their children has been observed [12]. Also dental treatments were suspected as risk factors for HEV contamination [13]. It has been reported that a substantial proportion of blood donors (3/200 or 1.5%) were positive for HEV RNA and viremic blood donors are potentially able to cause transfusion-associated hepatitis E in areas of high endemicity [14, 15]. Patients on chronic hemodialysis have an increased risk of exposure to nosocomially-transmitted agents, and the possibility of transmission of HEV in this group of patients had been raised. Reports on the prevalence and possible nosocomial transmission of HEV in patients on hemodialysis (HD) are scant. Some authors observed a high prevalence of anti-HEV antibody in their hemodialysis patients and hypothesized that the fecal-oral route may not be the only route of transmission of HEV among their patients [16]. Other investigators, in contrast, found few anti-HEV-positive patients in their HD populations [17, 18]. Moreover, in most of these reports a small number of patients were studied.

To our knowledge, the seroprevalence rate of anti- HEV among HD patients in Iran has not been examined. Iran is a country with few suspected outbreaks of HEV [19]. These findings prompted the present study to establish the prevalence of anti-HEV antibody among HD patients in the city of Tabriz in the northwestern part of Iran.

Methods

Patients

This study was carried out in Tabriz, northwestern part of Iran with about 3.5 million residents. We studied all patients (n = 324) on chronic hemodialysis treatment at three different dialysis units in Tabriz in August 2004. Routine HD techniques were performed with 3 or 4-hours treatments three times a week. Blood samples were obtained from all the patients for serological testing. Information was obtained from the medical records of the patients on the duration of hemodialysis and etiology of renal failure. In addition, a questionnaire was completed for each subject detailing the age, sex, and history of blood transfusion.

Laboratory assay

Blood samples were taken from each patient before the hemodialysis session, and the serum was separated without delay. Sera were stored at -20°C, coded and further tested at the laboratory of Research Center for Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases (Taleghani Hospital, Tehran) for anti-HEV IgG by enzyme immunometric assay (Diapro, Italy HEV EIA) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Cut-off was defined with positive and negative control sera that were included in each assay, according to manufacturer's instruction. Samples were considered positive if the optical density (OD) value was above the cut-off value and all positive samples were retested in duplicate with the same EIA assay to confirm the initial results. All patients were previously tested for HBs Ag (Diasorin, USA), anti-HCV (Third generation assay, Diasorin, USA) and anti-HIV (Biotest, Germany) by EIA assay.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS (version 11) statistical software (Scientific Package for Social Sciences, Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics were reported. Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± SD, and comparisons were performed with use of t-test for unpaired samples. The chi-square test, Fisher's exact test and Mann-Whitney test were used to compare the proportions between groups. The level of significance was set at a P value of <0.05. The study was endorsed by the responsible ethics committee.

Results

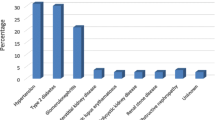

Three hundred and twenty four patients were tested. There were 190 (59%) males, and 134 (41%) females; the mean age (± SD) was 53.5 ± 15.1 years. The median duration of HD treatment was 27 months (range1–261 months). The chronic renal failure of the patients was due to glomerulonephritis (n = 113), diabetic nephropathy (n = 73), nephroangiosclerosis (n = 28), polycystic kidney disease (n = 22), chronic interstitial nephritis (n = 5) and other etiologies (n = 83). No patient admitted a history of intravenous drug use.

There were twenty-four of 324 chronic hemodialysis patients showing anti-HEV antibody, the anti-HEV prevalence in our population was 7.4% (95%CI: 4.6%–10.6%). There were 15/324(4.6%) patients with persistent HBV infection (HBs Ag positive) and 66/324 (20.4%) patients were anti-HCV antibody positive. All the patients were seronegative for anti-HIV antibody. Table 1 shows the patient characteristics in relation to the presence of HEV coinfection. No statistically significant difference was seen between anti-HEV positive and negative patients with respect to age, sex, incidence of blood transfusion and other blood borne infections (HBV, HCV, and HIV).

The duration of hemodialysis ranged between1 and 121 months (median 26) for anti-HEV positive patients and between 1 and 261 months (median 27) for the anti-HEV negative one with no significant difference (Mann-Whitney P = 0.73).

Discussion

Studies concerning HEV epidemiology among chronic HD patients are few and give conflicting results. Difference of HEV prevalence in the general population, the criteria for inclusion of patients, and the routes of HEV transmission could partially explain the diverse results found.

HEV is usually associated with the fecal-oral route, and blood is not considered an important cause of HEV transmission as the virus dose not produces a chronic carrier state [3]. However, experimental transmission of HEV to man showed a transient phase of viremia proceeding the onset of clinical symptoms and prolonged viremia has been observed in some patients [20–22]. Therefore, a theoretical possibility of HEV transmission in endemic areas via a parenteral route has been suggested. Such a possibility is supported by the observation that anti-HEV antibody is more frequent in transfusion recipients than in the same number of non-transfused controls [23].

We found that the prevalence of anti-HEV IgG was 7.4 % in chronic HD patients attending three different units in the city of Tabriz, northwestern part of Iran. There were few reports on suspected outbreaks of HEV in Iran [19] and a population-based study indicated that the prevalence rate of IgG anti-HEV among healthy population was 9.6% [24]. The observation that anti-HEV prevalence rate in HD patients in our study (7.4%) is lower than in the previous general population-based study (9.6%)might be due to differences in the population, the size of the sample studied or situation of public health services. In Iran, large cities have better public health services, such as clinics, municipal water and sewage systems, possibly explaining the reduced risk of infection. These factors need to be further evaluated.

The detection of IgG anti-HEV in 7.4% of chronic HD provides additional evidence that HEV is endemic in Iran. Similar findings have been reported from Saudi Arabia [25], where 7.2% of HD patients were detected for IgG anti- HEV. In contrast, the prevalence of IgG anti-HEV in patients at the hemodialysis unit of non- endemic countries was significantly low [26–28]. The prevalence of HEV vary in different hemodialysis units, relatively independent of the prevalence in the general population and probably reflect the difference in the epidemiological characteristics of HEV in areas of low and high endemicity [27, 29]. Apart from socioeconomic and environmental factors, intra-unit factors that may be associated with HEV transmission in some hemodialysis units needs to be evaluated further [29].

No statistically significant association was observed between HEV seropositivity and blood-borne viruses (HBV, HCV and HIV). One study has shown a striking association between hepatitis C and HEV, pointing to similar or overlapping routes of transmission [30]. Such an observation is in contrast with our finding. HEV infection, as detected by anti-HEV antibody, was associated with no risk factor in most patients.

Conclusion

This cross-sectional study showed a high prevalence of anti-HEV antibody in our HD Patients; we didn't find association between HEV and blood-borne viruses.

A careful surveillance in the general population is required and further appropriate investigations are needed to identify the exact mode of transmission and risk groups for this infection in Iran.

References

Pringle CR: Virus taxonomy-1999. The universal system of virus taxonomy, updated to include the new proposals ratified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses during 1998. Arch Virol. 1999, 144 (8): 421-429. 10.1007/s007050050515.

Virus Taxonomy: VIIIth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. [http://www-micro.msb.le.ac.uk/3035/HEV.html/]

Viswanathan R: A review of the literature on the epidemiology of infectious hepatitis. Indian J Med Res. 1957, 45 (Suppl): 145-155.

Khuroo MS: Study of an epidemic of non-A, non-B hepatitis. Possibility of another human hepatitis virus distinct from post-transfusion non-A, non-B type. Am J Med. 1980, 68: 818-824. 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90200-4.

Arora NK, Panda SK, Nanda SK, Ansari IH, Joshi S, Dixit R, Bathla R: Hepatitis E infection in children: study of an outbreak. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999, 14 (6): 572-577. 10.1046/j.1440-1746.1999.01916.x.

Naik SR, Aggarwal R, Salunke PN, Mehrotra NN: A large waterborne viral hepatitis E epidemic in Kanpur, India. Bull World Health Organ. 1992, 70 (5): 597-604.

Velazquez O, Stetler HC, Avila C, Ornelas G, Alvarez C, Hadler SC, Bradley DW, Sepulveda J: Epidemic transmission of enterically transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis in Mexico, 1986–1987. JAMA. 1990, 263: 3281-3285. 10.1001/jama.263.24.3281.

Balayan MS: Epidemiology of hepatitis E virus infection. J Viral Hepat. 1997, 4: 155-165. 10.1046/j.1365-2893.1997.00145.x.

Hussaini SH., Skidmore SJ, Richardson P, Sherratt LM, Cooper BT, O'Grady JG: Severe hepatitis E infection during pregnancy. J Viral Hepat. 1997, 4: 51-54. 10.1046/j.1365-2893.1997.00123.x.

Meng XJ: Novel strains of hepatitis E virus identified from humans and other animal species: is hepatitis E a zoonosis?. J Hepatol. 2000, 33: 842-845. 10.1016/S0168-8278(00)80319-0.

Halbur PG, Kasorndorkbua C, Gilbert C, Guenette D, Potters MB, Purcell RH, Emerson SU, Toth TE, Meng XJ: Comparative pathogenesis of infection of pigs with hepatitis E viruses recovered from a pig and a human. J Clin Microbiol. 2001, 39: 918-923. 10.1128/JCM.39.3.918-923.2001.

Khuroo MS, Kamili S, Jameel S: Vertical transmission of hepatitis E virus. Lancet. 1995, 345: 1025-1026. 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)90761-0.

Tassopoulos NC, Krawczynski K, Hatzakis A, Katsoulidou A, Delladetsima I, Koutelou MG, Trichopoulos D: Case report: role of hepatitis E virus in the etiology of community-acquired non-A, non-B hepatitis in Greece. J Med Virol. 1994, 42: 124-128.

Arankalle VA, Chobe LP: Hepatitis E virus: can it be transmitted parenterally?. J Viral Hepat. 1999, 6 (2): 161-164. 10.1046/j.1365-2893.1999.00141.x.

Arankalle VA, Chobe LP: Retrospective analysis of blood transfusion recipients: evidence for post-transfusion hepatitis E. Vox Sang. 2000, 79: 72-74. 10.1159/000031215.

Halfon P, Ouzan D, Chanas M, Khiri H, Feryn JM, Mangin L, Masseyef MF, Salvadori JM: High prevalence of hepatitis E virus antibody in haemodialysis patients (letter). Lancet. 1994, 344: 746-10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92232-2.

Courtney MG, O'Mahoney M, Albloushi S, Sachithanandan S, Walshe J, Carmody M, Donoghue J, Parfrey N, Shattock AG, Fielding J: Hepatitis E virus antibody prevalence (letter). Lancet. 1994, 344: 1166-10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90678-5.

Psichogiou M, Vaindirli E, Tzala E, Voudiclari S, Boletis J, Vosnidis G, Moutafis S, Skoutelis G, Hadjiconstantinou V, Troonen H, Hatzakis A: Hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection in hemodialysis patients. The Multicentre Hemodialysis Cohort Study on Viral Hepatitis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996, 11: 1093-1095.

Ariyegan M, Amini S: Hepatitis E epidemic in IRAN. J Med Council I.R.Irn. 1998, 15: 139-143.

Chauhan A, Jameel S, Dilawari JB, Chawla YK, Kaur U, Ganguly NK: Hepatitis E virus transmission to a volunteer. Lancet. 1993, 341: 149-150. 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90008-5.

Nanda SK, Ansari IH, Acharya SK, Jameel S, Panda SK: Protracted viremia during acute sporadic hepatitis E virus infection. Gastroenterology. 1995, 108: 225-230.

Schlauder GG, Dawson GJ, Mushahwar IK, Ritter A, Sutherland R, Moaness A, Kamel MA: Viremia in Egyptian children with hepatitis E virus infection. (Letter). Lancet. 1993, 341: 78-10.1016/0140-6736(93)90187-L.

Mannucci PM, Gringeri A, Santagostino E, Romano L, Zanetti A: Low risk of transmission of hepatitis E virus by large-pool coagulation factor concentrates. (Letter). Lancet. 1994, 343: 597-598. 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)91548-2.

Zali MR, Taremi M, Arabi SMM, Ardalan A, Alizadeh AHM, Ansari SH: Seroprevalence of Hepatitis E in Nahavand, Iran: A population-based study. proceeding of the Digestive Diseases week, 15–19. 2004, May ; New Orleans, USA

Ayoola EA, Want MA, Gadour MOEH, Al-Hazmi MH, Hamza MKM: Hepatitis E Virus Infection in Hemodialysis Patients: A Case-Control Study in Saudi Arabia. J Med Virol. 2002, 66: 329-334. 10.1002/jmv.2149.

Fabrizi F, Lunghi G, Bacchini G, Corti M, Pagano A, Locatelli F: Hepatitis E virus infection in hemodialysis patients: a seroepidemiological survey. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997, 12: 133-136. 10.1093/ndt/12.1.133.

Staffan PES, Stefan HJ, Brith C: Prevalence of Antibodies to Hepatitis E Virus Among Hemodialysis Patients in Sweden. J Med Virol. 1998, 54: 38-43. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199801)54:1<38::AID-JMV6>3.0.CO;2-Q.

Trinta KS, Liberto MI, Paula VS, Yoshida CF, Gaspar AM: Hepatitis E virus infection in selected Brazilian populations. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001, 96: 25-29. 10.1590/S0074-02762001000100004.

Dalekos GN, Zervou E, Elisaf M, Germanos N, Galanakis E, Bourantas K, Siamopoulos KC, Tsianos EV: Antibodies to hepatitis E virus among several population in Greece: increased prevalence in an hemodialysis unit. Transfusion. 1998, 38: 589-595. 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1998.38698326339.x.

Pisanti FA, Coppola A, Galli C: Association between hepatitis C and hepatitis E viruses in southern Italy. Lancet. 1994, 344: 746-747. 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92233-0.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/5/36/prepub

Acknowledgements

This study was funded in part by the Drug Applied Research Center (DARC), Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. We wish to express our gratitude and thanks to Dr. T. Shahnazi, Dr. M. M. Arabi and Mr. K. Zolfagharian for their excellent technical assistance, Dr. S. Abediazar and Dr. H. Argani, Department of Nephrology, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for supplying the patients' sera.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MT raised the original idea and design of the study and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. MK conceived the study, and participated in its design and coordination.

LG participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. MJE and MRZ revised the draft manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Taremi, M., Khoshbaten, M., Gachkar, L. et al. Hepatitis E virus infection in hemodialysis patients: A seroepidemiological survey in Iran. BMC Infect Dis 5, 36 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-5-36

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-5-36