Abstract

Background

Micrococcus species may cause intracranial abscesses, meningitis, pneumonia, and septic arthritis in immunosuppressed or immunocompetent hosts. In addition, strains identified as Micrococcus spp. have been reported recently in infections associated with indwelling intravenous lines, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis fluids, ventricular shunts and prosthetic valves.

Case presentation

We report on the first case of a catheter-related bacteremia caused by Kocuria rosea, a gram-positive microorganism belonging to the family Micrococcaceae, in a 39-year-old man undergoing peripheral blood stem cell transplantation due to relapsed Hodgkin disease. This uncommon pathogen may cause opportunistic infections in immunocompromised patients.

Conclusions

This report presents a case of Kocuria rosea catheter related bacteremia after stem cell transplantation successfully treated with vancomycin and by catheter removal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Long-term indwelling central venous access devices are indispensable to the supportive care of cancer patients. Infection remains a major complication of Hickman type catheters [1]. Intravascular catheter-related infections can be the cause of morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation (PBSCT). Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci, aerobic gram-negative bacilli and Candida albicans are the most frequent causes of catheter related bloodstream infection [2]. Kocuria rosea, is gram-positive, strictly aerobic microorganisms belonging to the family Micrococcaceae that usually grow on simple media and generally considered as non-pathogenic commensals that colonize the oropharynx, skin and mucosa. However, it can be opportunistic pathogen in the immunocompromised patient [3, 4].

We describe the first case of central venous catheter (CVC) related infection associated with Kocuria rosea in a patient undergoing autologous PBSCT. He had a chills, high fever, tachycardia and increased respiratory rate. Persistent bacteremia, which was unresponsive to vancomycin, was successfully treated by catheter removal.

Case presentation

A 39-year-old man with relapsed Hodgkin disease was admitted to Erciyes University Hospital for autologous PBSCT. A Hickman-type central venous catheter was implanted and the patient received a conditioning regimen consisting ifosfamide, carboplatin and etoposide. On day 3 after PBSCT, he was acutely ill with a chills, high fever (temperature 38.5°C), tachycardia (heart rate 108 beats/min) and increased respiratory rate (26 breaths/min). Clinical, radiological and microbiological diagnostic procedures were performed, and at three blood cultures were obtained from peripheral veins and catheter half an hour apart. The patient was empirically treated with intravenous imipenem/cilastatin, 2 g/day; and amikacin, 1 g/day. On day six after PBSCT, he had a persistent fever and the temperature spiked to 39.5°C. There was no sign of a catheter exit-site infection. Chest radiography was normal. Serial blood cultures taken from the catheter (two cultures) and a peripheral vein (four cultures) were positive for Micrococcus spp., which were identified as Kocuria rosea. An antibiogram showed that the pathogen was sensitive to ampicillin/sulbactam, erythromycin and vancomycin. Imipenem and amikacin were discontinued, and intravenous vancomycin, 2 g/day was begun. The patient did not respond satisfactorily to vancomycin therapy for five consecutive days. The catheter was removed and a catheter tip culture was obtained. The cultures demonstrated a massive growth of Kocuria rosea. Blood cultures were thereafter negative. The patient was discharged from the hospital after 14 days of intravenous vancomycin. He was followed for six months; the patient is alive and well and is in complete remission of the primary disease.

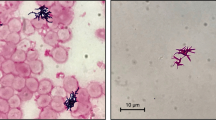

Microbiological diagnosis

Cultures of blood from the peripheral veins and the CVC were performed with a BACTEC system (BACTEC 9210; Becton Dickinson). The CVC tip was cultured by using the Maki roll technique. A growth of more than 15 cfu on the blood agar plate was considered positive. It was identified as Kocuria rosea on the basis of Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology [5]. This identification was confirmed with the commercially available tests (ID32 Staph ATB system, and mini-API, Biomerieux).

Discussion

Micrococcus spp. are usually regarded as non-pathogenic skin commensals and their clinical relevance is questionable. However, Micrococcus spp. can be opportunistic pathogens in immunocompromised patients such as PBSCT. It has been reported that Micrococcus luteus has been implicated as the causative agent in cases of intracranial abscesses, meningitis, pneumonia and septic arthritis in immunosuppressed or immunocompetent hosts [6–12]. In addition, strains identified as Micrococcus spp. have been reported recently in infections associated with indwelling intravenous lines, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis fluids, ventricular shunts and prosthetic valves [13–18].

We performed a Medline search using the terms "Micrococcus" and/or "Kocuria rosea" and/or "Kocuria". However, we were unable to find published studies on catheter infections caused by Kocuria rosea in patients undergoing HSCT in febrile neutropenic period.

In this patient, the repeated isolation of Kocuria rosea from different blood cultures in the absence of other microorganisms, together with isolation of the same organism from the catheter were primarily responsible for the episodes of febrile neutropenia. The catheter was then removed and cultures demonstrated a massive growth of Kocuria rosea.

The clinician should not underestimate the importance of the repeated isolation of a Kocuria rosea from blood cultures. Although uncommon, the possibility that a central venous line may be the portal of entry should be evaluated. Adherence of bacteria to the silastic tube would possibly explain the failure of treatment by antibiotics alone.

Conclusions

This report emphasizes that Kocuria rosea should be considered as a nosocomial pathogen, which may cause of catheter infections in febrile neutropenic patients. In these patients, persistent Kocuria rosea bacteremia unresponsive to medical management should be treated by catheter removal.

References

Mermel LA, Farr BM, Sherertz RJ, Raad II, O'Grady N, Harris JS: Guidelines for the management of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2001, 32: 1249-1272. 10.1086/320001.

Maki DG, Mermel LA: Infections due to infusion theraphy. In Hospital infections. Edited by: Bennett JV, Brachman PS. 1988, Philedelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 689-724.

Adang RP, Schouten HC, van Tiel FH, Blijham GH: Pneumonia due to Micrococcus spp. in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 1992, 6: 224-226.

Magee JT, Burnett IA, Hindmarch JM, Spencer RC: Micrococcus and Stomacoccus spp. from human infections. J Hosp Infect. 1990, 16: 67-73. 10.1016/0195-6701(90)90050-X.

Schleifer KH: Gram-positive cocci. In Bergey' manual of systematic bacteriology. Edited by: Sneath PHA, Mair NS, Sharpe ME, Holt JG. 1986, Baltimore: The Williams & Wilkins Co, 2: 999-1103.

Selladurai B, Sivakumaran S, Subramanian A, Mohamad AR: Intracranial suppuration caused by Micrococcus luteus. Br J Neurosurg. 1993, 7: 205-208.

Fosse T, Peloux Y, Granthil C, Toga B, Bertrando J, Sethian M: Meningitis due to Micrococcus luteus. Infection. 1985, 13: 280-281.

Wharton M, Rice JR, McCallum R, Gallis HA: Septic arthritis due to Micrococcus luteus. J Rheumatol. 1986, 13: 659-660.

Peces R, Gago E, Tejada F, Laures AS, Alvarez-Grande J: Relapsing bacteraemia due to Micrococcus luteus in a haemodialysis patient with a Perm-Cath cathether. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997, 12: 2428-2429. 10.1093/ndt/12.11.2428.

Souhami L, Feld R, TuVnell PG, Fellner T: Micrococcus luteus pneumonia: a case report and review of the literature. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1979, 7: 309-314.

Adang RP, Schouten HC, van Tiel FH, Blijham GH: Pneumonia due to Micrococcus spp. in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 1992, 6: 224-226.

von Eiff C, Kuhn N, Herrman M, Weber S, Peters G: Micrococcus luteus as a cause of recurrent bacteremia. Pediatr J Infect Dis. 1996, 15: 711-713. 10.1097/00006454-199608000-00019.

Shapiro S, Boaz J, Kleiman M, Kalsbeek J, Mealy J: Origin of organisms infecting ventricular shunts. Neurosurgery. 1988, 22: 868-872.

Kiehn TE, Armstrong D: Changes in the spectrum of organisms causing bacteraemia and fungemia in immunocompromised patients due to venous access devices. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990, 9: 869-872.

Pople IK, Bayston R, Hayward RD: Infection of cerebrospinal fluid shunts in infants: a study of etiological factors. J Neurosurg. 1992, 77: 29-36.

Spencer RC: Infections in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1988, 27: 1-9.

Ambler MW, Homans AC, O'Shea PA: An unusual central nervous system infection in a young immunocompromised host. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986, 110: 497-501.

Richardson JF, Marples RR, de Saxe MJ: Characters of coagulase-negative staphylococci and micrococci from cases of endocarditis. J Hosp Infect. 1984, 5: 164-171. 10.1016/0195-6701(84)90120-8.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/4/62/prepub

Acknowledgements

Written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

FA, OY and KG carried out the clinical study of the patient. BS carried out the culture and specific identification of the bacterium. BE and MC drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Altuntas, F., Yildiz, O., Eser, B. et al. Catheter-related bacteremia due to Kocuria rosea in a patient undergoing peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. BMC Infect Dis 4, 62 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-4-62

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-4-62