Abstract

Background

Few data are available on antiretroviral therapy (ART) response among HIV-2 infected patients. We conducted a systematic review on treatment outcomes among HIV-2 infected patients on ART, focusing on the immunological and virological responses in adults.

Methods

Data were extracted from articles that were selected after screening of PubMed/MEDLINE up to November 2012 and abstracts of the 1996–2012 international conferences. Observational cohorts, clinical trials and program reports were eligible as long as they reported data on ART response (clinical, immunological or virological) among HIV-2 infected patients. The determinants investigated included patients’ demographic characteristics, CD4 cell count at baseline and ART received.

Results

Seventeen reports (involving 976 HIV-2 only and 454 HIV1&2 dually reactive patients) were included in the final review, and the analysis presented in this report are related to HIV-2 infected patients only. There was no randomized controlled trial and only two cohorts had enrolled more than 100 HIV-2 only infected patients. The median CD4 count at ART initiation was 165 cells/mm3, [IQR; 137–201] and the median age at ART initiation was 44 years (IQR: 42–48 years). Ten studies included 103 patients treated with three nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI). Protease inhibitor (PI) based regimens were reported by 16 studies. Before 2009, the most frequent PIs used were Nelfinavir and Indinavir, whereas it was Lopinavir/ritonavir thereafter. The immunological response at month-12 was reported in six studies and the mean CD4 cell count increase was +118 cells/μL (min-max: 45–200 cells/μL).

Conclusion

Overall, clinical and immuno-virologic outcomes in HIV-2 infected individuals treated with ART are suboptimal. There is a need of randomized controlled trials to improve the management and outcomes of people living with HIV-2 infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection is responsible for most of the global AIDS pandemic, HIV type 2 (HIV-2) is not infrequent in West Africa and is an additional and important cause of burden of disease with a limited spread to other regions of the world [1–3]. Overall in West Africa, between 10 and 20% of HIV infections include HIV-2 with a significant proportion of dually infected or reactive HIV-1 + 2 individuals [4, 5]. Interestingly, the prevalence of HIV-2 infections seems to be declining in West Africa, although the reasons remain unclear [1, 6–9]. Compared to HIV-1, HIV-2 infection is characterized by a longer clinical asymptomatic latency period [10], a slower T lymphocyte CD4 (CD4) depletion [11, 12] and a lower plasma viral load (VL) [13, 14]. Nevertheless, HIV-2 infection can lead to clinical AIDS [15, 16] and death [17–19] and such patients may clearly benefit from antiretroviral therapy (ART).

The 2013 World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines recommended the combined use of either three nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) or two NRTIs plus one protease inhibitor (PI) as the initial ART regimen for HIV-2 infection in a public health approach, [20]. These guidelines were based on observational studies with limited data. Their application could lead to the unavailability of effective second-line agents for HIV-2 infected patients in areas with limited access to ART, since phenotypic cross-resistance with PIs as well as NRTIs is a significant issue for HIV-2 [21–25].

No randomized clinical trial has assessed the efficacy of specific ART regimens in treatment-naïve HIV-2–infected patients [26, 27]. However, observational cohort studies in developed countries [15, 28, 29] have reported different and generally poorer treatment responses in HIV-2 patients compared to HIV-1 patients. Similar results were reported in a larger cohort collaboration in West Africa [30]. Additionally, data from few cohort studies conducted in resource-limited settings, such as Senegal [23–25], Gambia [18, 31–33], Cote-d’Ivoire [34] are focused generally on treatment outcomes or genotyping resistance mutation in HIV-2 infected patients.

Data comparing different ARV regimens among HIV-2 patients are even scarcer. Only one European cohort study has reported better immunological and virological responses to ritonavir-boosted PI-containing ART in antiretroviral-naïve HIV-2–infected patients compared to three NRTIs [15]. Overall, there has been minimal evidence-based recommendation regarding the best use of ART for HIV-2 infection [20, 33, 35–37]. We initiated this systematic review on ART response among HIV-2 and HIV-1/HIV-2 dually infected patients, to describe the different ART options that have been used and the different outcomes of these treatments.

Methods

We conducted this systematic review according to the criteria set forth by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) group [38].

Eligibility criteria

All studies, without design, place or language restrictions, were considered if they met the following four selection criteria: 1) data on clinical response (death or worsening of WHO stage), 2) data on immunological or virological response or both, sorted by ART regimen, 3) at least five patients receiving each drug regimen, 4) an available abstract, an article or an oral poster presentation. We included retrospective and prospective studies that reported responses to ART among HIV-2 and HIV-1/HIV-2 dually infected patients whatever the first-line regimen received. We excluded the case series with less than five patients. We also excluded studies that only reported data on genotypic analysis or only the prevalence of HIV-2 infection, or natural history.

Search strategy and study selection

We developed a sensitive search strategy that combined terms for HIV-2 and ART (HAART or antiretroviral therapy or highly active or antiretroviral or therapy or highly active antiretroviral therapy, drug resistance, viral drug resistance).

(“hiv-2”[MeSH Terms] OR “hiv-2”[All Fields] OR “hiv 2”[All Fields]) AND (“drug resistance, viral”[MeSH Terms] OR (“drug”[All Fields] AND “resistance”[All Fields] AND “viral”[All Fields]) OR “viral drug resistance”[All Fields] OR (“drug“[All Fields] AND “resistance“[All Fields] AND “viral“[All Fields]) OR “drug resistance, viral“[All Fields]) AND (“1996“[PDAT]: “2012“[PDAT]):

(“hiv-2“[MeSH Terms] OR “hiv-2“[All Fields] OR “hiv 2“[All Fields]) AND (“antiretroviral therapy, highly active”[MeSH Terms] OR (“antiretroviral”[All Fields] AND “therapy”[All Fields] AND “highly”[All Fields] AND “active”[All Fields]) OR “highly active antiretroviral therapy”[All Fields] OR “haart“[All Fields]) AND (“1996“[PDAT]: “2012“[PDAT])

Initial searches were developed (DKE) for the following databases (from 1996 to November 1st, 2012): MEDLINE via PubMed, EMBASE, LILACS, Web of Science, Current Controlled Trials (http://www.controlled-trials.com), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. MEDLINE search was subsequently updated to November 1st, 2012. We also searched the data available on websites of International AIDS Society (IAS) conferences and of the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) and International Conference for AIDS in Africa (ICASA). We particularly searched for abstracts from conferences held between July 2009 and July 2012 in order to identify studies that were recently completed but were possibly not yet published as full text articles. Bibliographies of relevant review articles and other papers were also screened. One of the authors (DKE) did a preliminary search, scanning all titles for eligibility according to the predefined inclusion criteria. The full abstracts of potentially eligible studies were then scanned by additional two reviewers (PC, JT) who worked independently to select potentially relevant full-text articles. Once all relevant full-text articles were reviewed, final agreement on study inclusion was determined through consensus (PC, DKE, JT and SPE).

Data extraction and quality assessment

To decide whether or not the eligible studies met the inclusion criteria, each report was assessed by two independent reviewers (DKE, PC) using a standardized selection form developed for this purpose. Disagreements between observers were resolved by discussion. Data extraction was also conducted by the same reviewers using a standardized data extraction form created for this study and with the collaboration of external experts, when needed (JT, SPE). The following information was obtained from each study: first author’s name, journal and year of publication/presentation, design of the study, patient characteristic at baseline, location of the study, ART details, baseline median plasma HIV-2 VL, baseline CD4 count and length of follow-up. Each cohort was divided into categories according to ART used: PI-based regimen vs three NRTIs or other.

Outcome measures

The outcomes of interest were the immunological response at 6, 12, 24 and 36 months (or equivalent time in weeks), the virological response at 12 and 24 months (as proportions at each time point) and the clinical progression including morbidity, ART discontinuation and mortality. The immunological and virological responses were considered when at least two measures of CD4 count or viral load at different moment were provided (one measure at baseline and at least one measure during follow up).

Data analysis

A wide variation in definitions, outcomes, and specific components of ART response evaluated in the studies was observed. This did not allow us to aggregate statistical analysis of findings beyond a basic descriptive level. We therefore began by describing each study, identifying the ART regimens initiated. We also described the different outcomes reported in each study. Where possible, we used the reported data to compute a 95% confidence interval (CI) for mortality, immunological response (increase of CD4 cell count) and virological response (proportion of patients with VL below the detectable threshold). We were not able to summarize the viral resistance mutations into one main result by lack of standardization. We used STATA® software to estimate the median with the inter-quartile range (IQR) for the quantitative variables.

Ethics statement

This systematic review was based on the data extraction of the articles published and was not therefore submitted to any ethic committee for a clearance.

Results

Study characteristics

Our search identified 915 papers and abstracts after removing duplicates. Of these, 835 were excluded on the basis of title and 39 others were excluded on the basis of content of the abstracts. Finally, after a full text screen, 25 reports were excluded because of insufficient information or target population only made up of HIV-1&2 dually reactive patients. One additional report from CROI web site was added. Altogether, 17 reports were included in the final review according to our eligibility criteria (Figure 1). There were no randomized trials, 15 cohort studies and two case series. Although the epicentre of HIV-2 is West Africa, it contributed only 8 studies, one was conducted in India, another in the USA, six in Europe and one study failed to adequately report the location. Ten studies involved HIV-2 infected patients only and the remaining included at least two or three sub-groups (HIV-2, HIV-1 and/or HIV-1&2 dually reactive) (Table 1).

Table 1 describes the characteristics of these 17 studies. Only two cohorts had enrolled more than 100 HIV-2 infected patients: one from Europe that recruited in six countries and enrolled 170 HIV-2 infected patients [15], and the other one from West Africa with the participation of sites in five countries and the enrolment of 270 HIV-2 infected patients [30]. For the remaining 15 studies, the sample size ranged from 5 to 91 HIV-2 infected patients.

The 17 reports contributed 1 430 patients, but only 976 were infected with HIV-2 only and constitute the core sample for this report. Their median age was 44 years (IQR: 42–48 years). All the studies selected provided a CD4 cell count at baseline except one from the Netherlands and the median CD4 cell count at ART initiation was 165 cells/mm3 (IQR: 138–203). Only six cohort studies reported a median CD4 cell count ≥200 cells/mm3 at baseline. The HIV-2 VL at baseline was reported in 10 studies (59%) and among them the median HIV-2 VL at ART initiation was 3.7 log10 copies/ml, IQR [2.9 - 4.5].

Table 2 describes the antiretroviral drug combinations used for the HIV-2 infected patients. Ten studies reported using three NRTIs for a total of 102 patients. Before 2009, the most frequently used PIs were Nelfinavir or Indinavir and Lopinavir/ritonavir-based regimens were used thereafter as heat-stable FDC tablets became widely available in West Africa..

Study outcomes

In our review, 14 studies (82%) reported immunological response, eight (47%) reported virological response, eight studies (47%) reported clinical events, and six (35%) reported data on loss to follow-up.

-

Mortality and loss to follow-up

A crude mortality rate was reported in eight cohorts without stratification by drug regimen (Table 3). The pooled crude mortality rate was 4.8% (37/771). Benard et al. in a French cohort study reported two deaths (6.9%) out of 29 HIV-2 infected patients followed up in median 26 months and treated with Lopinavir-ritonavir: one from a bladder cancer and another one from a lung cancer [28]. In the European cohort, no death was reported during the first 12 months of follow-up among 170 HIV-2 infected patients (126 initiated a PI-based regimen and 44 started with three NRTIs [15]). Studies from three developing countries reported mortality. Peterson in the Gambia reported six deaths among 51 HIV-2 infected patients (11.8%) followed up in median 20 months. In this latter study, the survival rate was 96% at 12 months and 80% at 36 months [18]. Smith in Senegal reported seven deaths among 74 HIV-2 infected patients (9.5%) followed up in median 13 months [43] and in Burkina Faso, Harries reported 14 deaths among 91 HIV-2 infected patients (15.4%) followed up in median 23 months [17]. Loss to follow-up was reported in six studies and varied between 0% in India [44] to 7.5% in Burkina-faso [17].

Table 3 Death and AIDS Progression among HIV-2 –infected patients in 17 studies -

AIDS progression

In the French cohort, none of the 18 HIV-2 patients with CDC stage A at baseline and treated with a PI-based regimen progressed to AIDS during follow-up. In the European Cohort, among the 170 HIV-2 infected patients enrolled (44 on three NRTIs), one patient (2%) receiving a triple NRTI regimen experienced progression to AIDS (tuberculosis) five months after treatment initiation. Among patients treated with PI/r, nine (7%) progressed to AIDS (cytomegalovirus infections [2], recurrent bacterial pneumonia [1], candidiasis [1], toxoplasmosis [1], cryptococcosis [1], pneumocystosis [1], HIV wasting syndrome [1], and unknown [1]) within a median delay of two months (min-max: 0.5–7.5 months) after treatment initiation [15].

-

CD4 response

The CD4 response was reported in 14 studies (Table 4). The median CD4 cell count increased at month-6 after ART initiation was +72 cells/μL (min-max: +41-140) cells/μL) based on four studies. In the French cohort [40], the median CD4 cell count did not differ between patients treated with a PI-containing regimen and those with three NRTIs at month-6 (P = 0.47) after treatment initiation. Always at month-6, in the group of patients without PI (n = 10), the median CD4 cell count increased was +57 (min-max: +37; +100) cells/μL whereas it was +52 (min-max: +8; +81) cells/μL among the 40 HIV-2 infected patients who had initiated a PI-containing regimen.

Table 4 Immunological responses* among HIV-2 –infected patients in 17 studies -

Overall, the median CD4 cell count increase at month 12 after ART initiation was +118 cells/μL (min-max: +45-200) cells/μL based on six studies. In France, at month 12 in the group of patients without PI (n = 9), the median CD4 cell count increase was +71 (min-max: +0; +90) cells/μL whereas it was +58 (min-max +11; +130) cells/μL among the 29 patients who had initiated a PI-containing regimen [40].

-

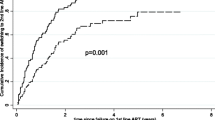

Only one study reported the immunological response at month-12 per drug regimen [15]. After three months of treatment, the estimated CD4 cell count decreased in patients treated with three NRTIs and increased in those treated with PI/r (-60 vs 176 cells/mm3/year in median; p = 0.002). These changes resulted in estimated CD4 cell counts at month 12 being lower in patients treated with three NRTIs than in patients treated with PI/r (191 vs 327 cells/mm3 in median; p = .001). The difference in estimated median CD4 cell counts at month 12 between patients treated with three NRTIs and those treated with a boosted PI-containing regimen remained statistically significant after adjustment for geographical origin (p = 0.0009) or for baseline HIV-2 RNA level (p = 0.05) [15].

-

Virological response

The virological response was reported in 11 studies (Table 5). The threshold of detection of HIV-2 VL varied from one study to another (min-max: 1.4-2.7 log10) (Table 5). Overall, among HIV-2 infected patients who initiated ART and had VL data available, 10% to 39% had an undetectable VL at baseline. In the Gambia, 81% of patients enrolled had their VL <400 copies/mL [18]. Ruelle et al. [42] in Belgium and Luxembourg reported that eight out of 13 HIV-2 infected patients (62%) had undetectable VL among patients who initiated a PI-based regimen. On the other hand, among patients who initiated a regimen without PI, one out of six (17%) had an undetectable VL at baseline. Three studies reported virological response data in patients who initiated a PI-based regimen or another regimen. Matheron et al. [40] reported a median change of VL of -1.0 (IQR -1.0; 00) log10 copies/ml among patients without PI whereas it was -0.6 (-1.7, 00) log10 copies/ml among patients who initiated a PI-based regimen. A similar report in the European cohort indicated a change of -1.8 log10 copies/ml among patients initiating a PI-based regimen and 0 log10 among patients who initiated ART with three NRTIs [15]. The proportion of patients with undetectable VL at 36 months was 81.4% in the Gambian study [18].

Table 5 Virological responses* among HIV-2 –infected patients in 17 studies

Discussion

This systematic review illustrates the heterogeneity of the reports of treatment outcomes of HIV-2 infected patients initiating ART, especially in resource-limited settings. Therefore, the global response on ART among HIV-2 infected patients remains difficult to synthesize. By the end of 2012, 17 publications reported usable information and only one study reported outcomes stratified by baseline CD4 cells count [15]. Our study highlights the need for standardized reporting of ART outcomes among HIV-2 infected patients akin those living with HIV-1.

To date, the use of VL for ART monitoring and initiation in HIV-2 infected patients has been a challenge for two reasons. First, there is no US or European-approved plasma VL test for HIV-2 infection, although assays are becoming increasingly available [47, 48], second, many HIV-2 infected patients eligible for ART have an undetectable VL. For example, in the European cohort, 39% of HIV-2 infected patients had an undetectable VL, though the median CD4 cell count at baseline was 191 cells/mm3 [IQR: 90–275]. Moreover, based on our recent experience in West Africa among patients with CD4 counts <500 cells/mm3, 76% and 47% of patients had an undetectable VL when considering thresholds of 50 copies/ml and 10 copies/ml, respectively [47]. Hence, it is more appropriate at this stage to use patients’ CD4 cell count and clinical stage for decision on ART initiation, as it has originally been the standard for HIV-1. However, there is no consensus on the level of CD4 cells count at which to start treatment for HIV-2. The US [37] and British ART guidelines [35] do not provide specific recommendations on the level of CD4 cells count at which ART should be initiated among asymptomatic HIV-2 infected patients. The 2010 French guidelines were the first ones to recommend ART initiation when the CD4 cell count was below 500 cells/mm3[46]. The WHO recommended the same threshold for HIV-2 and HIV-1 infected patients (CD4 < 350cells/ mm3) in the 2010 version [49] and now the same threshold for HIV-2 and HIV-1 (CD4 < 500 cells/mm3) in the recent 2013 recommendation as there was no evidence showing the benefit to start earlier in HIV-2 infected patients [20].

However in most of the reports reviewed, there seems to be a poorer CD4 cell count recovery after treatment initiation in HIV-2 infected patients compared to the HIV-1 infected ones [12]. This systematic review reveals that the median CD4 cell count at ART initiation was 165 cells/mm3 (IQR; 137–202), which is very close to the median CD4 count among HIV-1 infected patients in the same settings [12, 30]. Furthermore, the median age at ART initiation in this report was 44 years for HIV-2 infected patients (IQR; 42–46 years) and 37 years for the HIV-1 infected ones (Table 1) [30]. In older HIV-1-infected patient on ART, a poorer immunological response has previously been reported compared to younger ones in the same part of the world [50]. It can thus be assumed that poor immunological responses could also be expected among older HIV-2 infected patients. All the aforementioned argue in favor of early ART initiation among HIV-2 infected patients.

PI-based regimens (usually LPV/r) remains the first-line therapy most prescribed among HIV-2 infected patients in accordance with the different guidelines available [33, 35–37]. Data on three NRTI-based regimens, an alternative for lower-income countries in the context of the high prevalence of tuberculosis, are limited. The lack of large observational or randomized treatment studies in HIV-2 infected patients makes it difficult to decide at this stage when and which therapy should be started [26, 27]. Hence, there is an urgent need for randomized controlled trials to define the best sequencing of ART among HIV-2 infected patients, specifically in areas with limited access to second-line therapy based on alternative HIV-2 active PIs (Darunavir/r or Saquinavir/r) or integrase inhibitor-based regimens. In addition, optimizing the NRTI backbone in patients failing first-line regimens is an area that needs to be explored as data suggest a low barrier to class-wide NRTI resistance [51]. There is also no report on the switch of first-line regimens among HIV-2 infected patients. This could be explained by a lack of clear definition of treatment failure among HIV-2 infected patients [20, 35–37]. In HIV-2 infected patients with virological failure of first-line or subsequent regimens, genotypic resistance testing may be beneficial but interpretation algorithms are not well validated for most ARVs [52]. With this respect, introduction of new drugs and drug classes in countries with limited resources should be seriously considered.

This is to our knowledge the first systematic review on ART responses among HIV-2 infected patients including data from Europe, India and Africa. This review provides an overview of the different therapeutic strategies that have been used for HIV-2 infected patients so far, and their main outcomes, often documented in resource-limited settings but with limited evidence-based conclusions. Nonetheless, our review of available data should help to guide future studies and preferably clinical trials among HIV-2 infected patients.

We found substantial variations of ART responses reported over time and we were thus unable to identify any preferred ART regimen for HIV-2 infected patients. Only one study compared two different treatment regimens (PI-based vs. three NRTIs) [15]. In addition, the substantial heterogeneity in results observed between studies made it more difficult to determine the magnitude of the relative influence of individuals’ characteristics on treatment response. The main limitation of this review is the use of several patient populations probably overlapping each other, such as ANRS studies [12, 28, 53] and the Senegalese studies [25, 39] and the two international collaborative studies ACHIEV2E in Europe [15] and IeDEA West Africa [30, 54] Moreover, it was also challenging to analyze data in this review because each study reported the main outcomes in different manner. For example the CD4 count response was presented as an absolute difference delta or as a slope of CD4 count at different time points. It is therefore advisable to harmonize data presentation for future reports on ART response among HIV-2 infected patients. For example, CD4 slopes should be systematically reported as performed by the European and West Africa Collaborations [12, 15, 30]. For all the above, we were unable to pool the data extracted with different outcomes reported at different times and the overlapped study populations; hence we could not perform a meta-analysis.

Conclusion

In summary, our review did not find clear evidence on the response to different ART regimens used for HIV-2 infection mainly based on CD4 counts. This observation provides further justification to conduct randomized controlled trials among HIV-2 infected patients.

References

da Silva ZJ, Oliveira I, Andersen A, Dias F, Rodrigues A, Holmgren B, Anderssond S, Aaby P: Changes in prevalence and incidence of HIV-1, HIV-2 and dual infections in urban areas of Bissau, Guinea-Bissau: is HIV-2 disappearing?. AIDS. 2008, 22 (10): 1195-1202.

Gianelli E, Riva A, Rankin Bravo FA, Da Silva TD, Mariani E, Casazza G, Scalamogna C, Bosisio O, Adorni F, Rusconi S, Galli M: Prevalence and risk determinants of HIV-1 and HIV-2 infections in pregnant women in Bissau. J Infect. 2010, 61 (5): 391-398.

Mansson F, Camara C, Biai A, Monteiro M, da Silva ZJ, Dias F, Alves A, Andersson S, Fenyö EM, Norrgren H, Unemo M: High prevalence of HIV-1, HIV-2 and other sexually transmitted infections among women attending two sexual health clinics in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. Int J STD AIDS. 2010, 21 (9): 631-635.

Chang LW, Osei-Kwasi M, Boakye D, Aidoo S, Hagy A, Curran JW, Vermund SH: HIV-1 and HIV-2 seroprevalence and risk factors among hospital outpatients in the Eastern Region of Ghana, West Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002, 29 (5): 511-516.

Rouet F, Ekouevi DK, Inwoley A, Chaix ML, Burgard M, Bequet L, Viho I, Leroy V, Simon F, Dabis F, Rouzioux C: Field evaluation of a rapid human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serial serologic testing algorithm for diagnosis and differentiation of HIV type 1 (HIV-1), HIV-2, and dual HIV-1-HIV-2 infections in West African pregnant women. J Clin Microbiol. 2004, 42 (9): 4147-4153.

Eholie S, Anglaret X: Commentary: decline of HIV-2 prevalence in West Africa: good news or bad news?. Int J Epidemiol. 2006, 35 (5): 1329-1330.

Schmidt WP, Van Der Loeff MS, Aaby P, Whittle H, Bakker R, Buckner M, Dias F, White RG: Behaviour change and competitive exclusion can explain the diverging HIV-1 and HIV-2 prevalence trends in Guinea-Bissau. Epidemiol Infect. 2008, 136 (4): 551-561.

Tienen C, van der Loeff MS, Zaman SM, Vincent T, Sarge-Njie R, Peterson I, Leligdowicz A, Jaye A, Rowland-Jones S, Aaby P, Whittle H: Two distinct epidemics: the rise of HIV-1 and decline of HIV-2 infection between 1990 and 2007 in rural Guinea-Bissau. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010, 53 (5): 640-647.

van der Loeff MF, Awasana AA, Sarge-Njie R, van der Sande M, Jaye A, Sabally S, Corrah T, McConkey SJ, Whittle HC: Sixteen years of HIV surveillance in a West African research clinic reveals divergent epidemic trends of HIV-1 and HIV-2. Int J Epidemiol. 2006, 35 (5): 1322-1328.

Marlink R, Kanki P, Thior I, Travers K, Eisen G, Siby T, Traore I, Hsieh CC, Dia MC, Gueye EH: Reduced rate of disease development after HIV-2 infection as compared to HIV-1. Science. 1994, 265 (5178): 1587-1590.

Jaffar S, Wilkins A, Ngom PT, Sabally S, Corrah T, Bangali JE, Rolfe M, Whittle HC: Rate of decline of percentage CD4+ cells is faster in HIV-1 than in HIV-2 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997, 16 (5): 327-332.

Drylewicz J, Matheron S, Lazaro E, Damond F, Bonnet F, Simon F, Dabis F, Brun-Vezinet F, Chêne G, Thiébaut R: Comparison of viro-immunological marker changes between HIV-1 and HIV-2-infected patients in France. AIDS. 2008, 22 (4): 457-468.

Berry N, Ariyoshi K, Jaffar S, Sabally S, Corrah T, Tedder R, Whittle H: Low peripheral blood viral HIV-2 RNA in individuals with high CD4 percentage differentiates HIV-2 from HIV-1 infection. J Hum Virol. 1998, 1 (7): 457-468.

MacNeil A, Sarr AD, Sankale JL, Meloni ST, Mboup S, Kanki P: Direct evidence of lower viral replication rates in vivo in human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) infection than in HIV-1 infection. J Virol. 2007, 81 (10): 5325-5330.

Benard A, van Sighem A, Taieb A, Valadas E, Ruelle J, Soriano V, Calmy A, Balotta C, Damond F, Brun-Vezinet F, Chene G, Matheron S: Immunovirological response to triple nucleotide reverse-transcriptase inhibitors and ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors in treatment-naive HIV-2-infected patients: the ACHI(E)V(2E) collaboration study group. Clin Infect Dis. 2011, 52 (10): 1257-1266.

Martinez-Steele E, Awasana AA, Corrah T, Sabally S, van der Sande M, Jaye A, Togun T, Sarge-Njie R, McConkey SJ, Whittle H, van der Loeff MF S: Is HIV-2- induced AIDS different from HIV-1-associated AIDS? Data from a West African clinic. AIDS. 2007, 21 (3): 317-324.

Harries K, Zachariah R, Manzi M, Firmenich P, Mathela R, Drabo J, Onadja G, Arnould L, Harries A: Baseline characteristics, response to and outcome of antiretroviral therapy among patients with HIV-1, HIV-2 and dual infection in Burkina Faso. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010, 104 (2): 154-161.

Peterson I, Togun O, de Silva T, Oko F, Rowland-Jones S, Jaye A, Peterson K: Mortality and immunovirological outcomes on antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 and HIV-2-infected individuals in the Gambia. AIDS. 2011, 25 (17): 2167-2175.

Toure S, Kouadio B, Seyler C, Traore M, Dakoury-Dogbo N, Duvignac J, Diakite N, Karcher S, Grundmann C, Marlink R, Dabis F, Anglaret X, Aconda Study Group: Rapid scaling-up of antiretroviral therapy in 10,000 adults in Cote d’Ivoire: 2-year outcomes and determinants. AIDS. 2008, 22 (7): 873-882.

WHO: Consolidated Guidelines On The Use Of Antiretroviral Drugs For Treating And Preventing Hiv Infection. Recommendations For A Public Health Approach. 2013, Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/download/en/index.html. Accessed date 13 February 2014

Mouroux M, Descamps D, Izopet J, Yvon A, Delaugerre C, Matheron S, Coutellier A, Valantin MA, Bonmarchand M, Agut H, Massip P, Costagliola D, Katlama C, Brun-Vezinet F, Calvez V: Low-rate emergence of thymidine analogue mutations and multi-drug resistance mutations in the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase gene in therapy-naive patients receiving stavudine plus lamivudine combination therapy. Antivir Ther. 2001, 6 (3): 179-183.

Rodes B, Toro C, Sheldon JA, Jimenez V, Mansinho K, Soriano V: High rate of proV47A selection in HIV-2 patients failing lopinavir-based HAART. AIDS. 2006, 20 (1): 127-129.

Gottlieb GS, Badiane NM, Hawes SE, Fortes L, Toure M, Ndour CT, Starling AK, Traore F, Sall F, Wong KG, Cherne SL, Anderson DJ, Dye SA, Smith RA, Mullins JI, Kiviat NB, Sow PS, University of Washington-Dakar HIV-2 Study Group: Emergence of multiclass drug-resistance in HIV-2 in antiretroviral-treated individuals in Senegal: implications for HIV-2 treatment in resouce-limited West Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2009, 48 (4): 476-483.

Gottlieb GS, Hawes SE, Wong KG, Raugi DN, Agne HD, Critchlow CW, Kiviat NB, Sow PS: HIV type 2 protease, reverse transcriptase, and envelope viral variation in the PBMC and genital tract of ARV-naive women in Senegal. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008, 24 (6): 857-864.

Gottlieb GS, Smith RA, Dia Badiane NM, Ba S, Hawes SE, Toure M, Starling AK, Traore F, Sall F, Cherne SL, Stern J, Wong KG, Lu P, Kim M, Raugi DN, Lam A, Mullins JI, Kiviat NB, Sow PS for the UW-Dakar HIV-2 Study Group: HIV-2 integrase variation in integrase inhibitor-naive adults in Senegal, West Africa. PLoS One. 2011, 6 (7): e22204-

Gottlieb GS, Eholie SP, Nkengasong JN, Jallow S, Rowland-Jones S, Whittle HC, Sow PS: A call for randomized controlled trials of antiretroviral therapy for HIV-2 infection in West Africa. AIDS. 2008, 22 (16): 2069-2072. discussion 73–4

Matheron S: HIV-2 infection: a call for controlled trials. AIDS. 2008, 22 (16): 2073-2074.

Benard A, Damond F, Campa P, Peytavin G, Descamps D, Lascoux-Combes C, Taieb A, Simon F, Autran B, Brun-Vézinet F, Chêne G, Matheron S: Good response to lopinavir/ritonavir-containing antiretroviral regimens in antiretroviral-naive HIV-2-infected patients. AIDS. 2009, 23 (9): 1171-1173.

van der Ende ME, Prins JM, Brinkman K, Keuter M, Veenstra J, Danner SA, Niesters HG, Osterhaus AD, Schutten M: Clinical, immunological and virological response to different antiretroviral regimens in a cohort of HIV-2-infected patients. AIDS. 2003, 17 (Suppl 3): S55-S61.

Drylewicz J, Eholie S, Maiga M, Zannou DM, Sow PS, Ekouevi DK, Peterson K, Bissagnene E, Dabis F, Thiébaut R, International epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) West Africa Collaboration: First-year lymphocyte T CD4+ response to antiretroviral therapy according to the HIV type in the IeDEA West Africa collaboration. AIDS. 2010, 24 (7): 1043-1050.

Jallow S, Alabi A, Sarge-Njie R, Peterson K, Whittle H, Corrah T, Cotten M, Vanham G, McConkey SJ, Rowland-Jones S, Janssens W: Virological response to highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) and in patients dually infected with HIV-1 and HIV-2 in the Gambia and emergence of drug-resistant variants. J Clin Microbiol. 2009, 47 (7): 2200-2208.

Jallow S, Kaye S, Alabi A, Aveika A, Sarge-Njie R, Sabally S, Corrah T, Whittle H, Vanham G, Rowland-Jones S, Janssens W, McConkey SJ: Virological and immunological response to Combivir and emergence of drug resistance mutations in a cohort of HIV-2 patients in The Gambia. AIDS. 2006, 20 (10): 1455-1458.

Peterson K, Jallow S, Rowland-Jones SL, de Silva TI: Antiretroviral therapy for HIV-2 infection: recommendations for management in low-resource settings. AIDS Res Treat. 2011, 2011: 463704-

Adje-Toure CA, Cheingsong R, Garcia-Lerma JG, Eholie S, Borget MY, Bouchez JM, Otten RA, Maurice C, Sassan-Morokro M, Ekpini RE, Nolan M, Chorba T, Nkengasong JN HW: Antiretroviral therapy in HIV-2-infected patients: changes in plasma viral load, CD4+ cell counts, and drug resistance profiles of patients treated in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. AIDS. 2003, 17 (Suppl 3): S49-S54.

Gilleece Y, Chadwick DR, Breuer J, Hawkins D, Smit E, McCrae LX, Pillay D, Smith N, Anderson J, BHIVA Guidelines Subcommittee: British HIV Association guidelines for antiretroviral treatment of HIV-2-positive individuals 2010. HIV Med. 2010, 11 (10): 611-619.

Morlat P: Prise en Charge Medicale Des Personnes Vivant Avec Le VIH. Recommandations Du Groupe D’experts. Rapport. 2013, Available from: http://www.sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Rapport_Morlat_2013_Mise_en_ligne.pdf. Accesed date 13 February 2014, . Sous la direction du Pr. Philippe Morlat et sous l’égide du CNS et de l’ANRS. 2013

New York State HIV Guidelines- NEW: Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 2 (HIV-2). Available from: http://www.natap.org/2012/newsUpdates/041712_03.htm. Accesed date 13 February 2014

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6 (7): e1000097-doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Mullins C, Eisen G, Popper S, Dieng Sarr A, Sankale JL, Berger JJ, Wright SB, Chang HR, Coste G, Cooley TP, Rice P, Skolnik PR, Sullivan M, Kanki PJ: Highly active antiretroviral therapy and viral response in HIV type 2 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2004, 38 (12): 1771-1779.

Matheron S, Damond F, Benard A, Taieb A, Campa P, Peytavin G, Pueyo S, Brun-Vezinet F, Chene G, ANRS CO5 HIV2 Cohort Study Group: CD4 cell recovery in treated HIV-2-infected adults is lower than expected: results from the French ANRS CO5 HIV-2 cohort. AIDS. 2006, 20 (3): 459-462.

Ndour CT, Batista G, Manga NM, Gueye NF, Badiane NM, Fortez L, Sow PS: Efficacy and tolerance of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-2 infected patients in Dakar: preliminary study. Med Mal Infect. 2006, 36 (2): 111-114.

Ruelle J, Roman F, Vandenbroucke AT, Lambert C, Fransen K, Echahidi F, Piérard D, Verhofstede C, Van Laethem K, Delforge ML, Vaira D, Schmit JC, Goubau P: Transmitted drug resistance, selection of resistance mutations and moderate antiretroviral efficacy in HIV-2: analysis of the HIV-2 Belgium and Luxembourg database. BMC Infect Dis. 2008, 8: 21-

Smith CJ: Toward Optimal ART for HIV-2 Infection: Can Genotypic and Phenotypic Drug Resistance Testing Help Guide Therapy in HIV-2? (Paper # 579). 2010, San-Francisco, USA: 17th Conference on Retoviruses and Opportunistic Infections

Chiara M, Rony Z, Homa M, Bhanumati V, Ladomirska J, Manzi M, Wilson N, Harries AD AD: Characteristics, immunological response & treatment outcomes of HIV-2 compared with HIV-1 & dual infections (HIV 1/2) in Mumbai. Indian J Med Res. 2010, 132: 683-689.

Peterson K, Ruelle J, Vekemans M, Siegal FP, Deayton JR, Colebunders R: The role of raltegravir in the treatment of HIV-2 infections: evidence from a case series. Antivir Ther. 2012, 17 (6): 1097-1100.

Yeni P: Prise en charge médicale des personnes infectées par le VIH. Recommandations du groupe d’experts. Rapport. 2010, Available from: http://www.sante.gouv.fr/rapports,54.html. Accesed date 13 February 2014, . Sous la direction du Pr. Patrick Yeni 2010

Ekouevi DK, Anglaret X, Coffie PA, Eugène M, Minga A, Eholie SP, Avettand-Fénoël V, Plantier JC, Damond F, Dabis F, Rouzioux C, for the IeDEA West Africa collaboration: Plasma HIV-2 RNA According to CD4 Count Strata Among Untreated HIV-2-Infected Adults in Côte d’Ivoire: The IeDEA West Africa Collaboration. 7th International Aids Society Conference. 30 June-3July 2013 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (abstract TUPE267)

Chang M, Gottlieb GS, Dragavon JA, Cherne SL, Kenney DL, Hawes SE, Smith RA, Kiviat NB, Sow PS, Coombs RW: Validation for clinical use of a novel HIV-2 plasma RNA viral load assay using the Abbott m2000 platform. J Clin Virol. 2012, 55 (2): 128-133.

WHO: Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents. Recommendations for a Public Health Approach: 2010 Revision. 2010, Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/arv/adult2010/en/index.html. Accesed date 13 February 2014

Balestre E, Eholie SP, Lokossue A, Sow PS, Charurat M, Minga A, Drabo J, Dabis F, Ekouevi DK, Thiébaut R, International epidemiological Database to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) West Africa Collaboration: Effect of age on immunological response in the first year of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1-infected adults in West Africa. AIDS. 2012, 26 (8): 951-957.

Smith RA, Anderson DJ, Pyrak CL, Preston BD, Gottlieb GS: Antiretroviral drug resistance in HIV-2: three amino acid changes are sufficient for classwide nucleoside analogue resistance. J Infect Dis. 2009, 199 (9): 1323-1326.

Charpentier C, Eholié S, Anglaret X, Bertine M, Rouzioux C, Avettand-Fenoël V, Messou E, Minga A, Damond F, Plantier JC, Dabis F, Peytavin G, Brun-Vézinet F, Ekouevi DK, IeDEA West Africa Collaboration:: Genotypic resistance profiles of HIV-2-treated patients in West Africa. AIDS. 2014, 28 (8): 1161-1169. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000244

Matheron S, Descamps D, Boue F, Livrozet JM, Lafeuillade A, Aquilina C, Troisvallets D, Goetschel A, Brun-Vezinet F, Mamet JP, Thiaux C, CNA3007 Study Group: Triple nucleoside combination zidovudine/lamivudine/abacavir versus zidovudine/lamivudine/nelfinavir as first-line therapy in HIV-1-infected adults: a randomized trial. Antivir Ther. 2003, 8 (2): 163-171.

Ekouevi DK, Balestre E, Coffie PA, Minta D, Messou E, Sawadogo A, Minga A, Sow PS, Bissagnene E, Eholie SP, Gottlieb GS, Dabis F, IeDEA West Africa collaboration: Characteristics of HIV-2 and HIV-1/HIV-2 dually seropositive adults in West Africa presenting for care and antiretroviral therapy: the IeDEA-West Africa HIV-2 cohort study. PLoS One. 2013, 8 (6): e66135-

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/14/461/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all our colleagues on the IeDEA West Africa collaboration for their insights. We acknowledge Evelyne Mouillet (ISPED) for her assistance in the conduct of bibliographic research.

Funding

This systematic review was supported by funds from the HIV Department of the World Health Organization with additional support from the IeDEA West Africa consortium (The National Cancer Institute, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, support the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS [IeDEA] West Africa under Award Number U01AI069919. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions

DKE conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. BT participated in the design of the study, performed the statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. PC participated in the design of the study, performed the statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. JT participated in the design of the study and extracted data from the articles. AMA participated in the design of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. MV participated in the design of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. GSG participated in the design of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. FD participated in the design of the study analysis and helped to draft and revise the manuscript. SPE conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ekouevi, D.K., Tchounga, B.K., Coffie, P.A. et al. Antiretroviral therapy response among HIV-2 infected patients: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis 14, 461 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-461

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-461