Abstract

Background

The increasing occurrence of multidrug resistant (MDR) bacteria arises at a time when there is a lack of antibiotics active against these pathogens and few new antimicrobials are in the pipelines of the pharmaceutical industry. Treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) caused especially by MDR Gram-negative bacilli (GNB) represents a real challenge due to the dearth of treatment options.

Methods

We searched the medical literature relevant about management of ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by multi-drug resistant pathogens including GNB and methicillin-resistant S. aureus.

Results

Empirical therapy should be prescribed based on the local pattern of susceptibilities. Colistin and tigecycline are in many cases the unique options for the treatment of many episodes of VAP caused by MDR-GNB. Tigecyline (not licensed for treatment of pneumonia) should be used with an initial bolus of 200 mg followed by 100 mg every 12 h. The need for a loading dose and the administration of high doses of colistin (9 million IU/day in two or three doses) is currently accepted. Vancomycin has been considered the treatment of choice for pneumonia due to MRSA although linezolid may provide higher rate of clinical cure for MRSA VAP with a good safety profile. The initial antibiotic treatment must be reassessed and simplify in accordance of culture results.

Conclusions

Empirical treatment of VAP due to MDR pathogens should be based on knowledge of local ecology. A strategy combining early high doses of effective agents with subsequent simplification in the light of microbiologic information is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

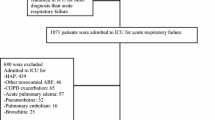

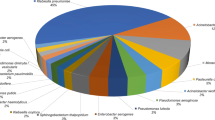

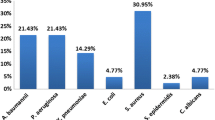

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is one of the most dreaded nosocomial infection. VAP appears to have a low attributable mortality although episodes caused by multi-drug resistant (MDR) pathogens is associated with a significant attributable mortality [1, 2]. Potential MDR pathogens include: P. aeruginosa, Acinetobacter spp, extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae, Klebsiella-producing carbapanamase strains, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).

In critically ill patients, the susceptibility of the bacteria isolated in a VAP depends on the duration of stay in the ICU and on mechanical ventilation as well as the previous use of antibiotics [3]. VAP has been conventionally classified into early and late onset. Early-onset VAP occurs within less than 96 hours of ICU admission and is generally due to antimicrobial-sensitive bacteria. Late-onset VAP occurs after 96 hours of ICU admission and may be caused by MDR pathogens. Other risk factors of MDR pathogens include prior antibiotic use within the preceding 90 days, frequency of antibiotic resistance in the community or hospital, and the immunocompromised state [4]. However, different studies have described a high rate of VAP due to MDR pathogens in episodes occurring in the first days of mechanical ventilation highlighting the importance of local ecology [5–7].

Diagnosing of VAP is difficult because it requires a thorough assessment of clinical data, radiological findings, and microbiological results. There are no foolproof tools to determine whether the patient has a VAP. When the clinical suspicion of VAP is high, empirical antimicrobial therapy must be initiated promptly because both delayed and inadequate treatments have been associated with increased rate of morbidity and mortality [4]. Nevertheless, one third of the patients with VAP only exhibit clinical criteria of sepsis [8]. In patients with no signs of severe sepsis or septic shock and no organisms present on Gram’s staining, antimicrobial therapy can be withheld pending culture results [9, 10].

Current guidelines recommend empirical coverage of Gram-negative bacilli (GNB) with a third or forth generation cephalosporin, piperacillin-tazobactam or a carbapenem in combination with a fluoroquinolone or an aminoglycoside [11]. However, the problem arises when a high proportion of the GNB are resistant to these antibiotics. One of the consequences of a greater prevalence of antimicrobial resistance is an increased recognition of inadequate antimicrobial treatment of infection. Few alternatives are available for treatment of these multi-drug resistant GNB.

Antibiotics for MDR-GNB

Carbapenems

Carbapenems have constituted the mainstay of VAP for many years. Imipenem, meropenem and doripenem have similar spectrum although doripenem is the most active carbapenem against P aeruginosa[12]. No carbapenem seems to be superior to another in clinical trials that have evaluated these agents in late-onset VAP [13, 14] or in VAP caused by P aeruginosa[15]. Optimization of carbapenem dosages (extended infusion of meropenem or doripenem) achieves improved pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic target attainments and is associated with higher rate of clinical cure in VAP [16, 17]. Dual-carbapenem therapy (ertapenem plus meropenem or doripenem) against KPC-producing K. pneumoniae has been evaluated in animal models [18]. The beneficial effect may be related to the KPC enzyme’s preferential affinity for ertapenem hindering doripenem or meropenem degradation and allowing the action of this carbapenem. A successful recovery with the use of this combination in a patient with bacteremic VAP due to pan-resistant KPC-producing K. pneumoniae has been recently reported [19].

Colistin

Polymyxins are a group of polypeptide cationic antibiotics. Only polymyxin B and polymyxin E (colistin) are used in clinical practice. Colistin acts in a way that does not promote cross-resistance and is unlikely to be associated with swift selection of resistant strains. Nowadays, colistin is the antimicrobial with the greatest level of in vitro activity against multi-drug resistant GNB including A baumannii, P aeruginosa, extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae or Klebsiella-producing carbapanamase strains. However, some GNB such as Proteus spp, Providencia spp, Morganella morganii and Serratia marcescens are resistant [20].

Over the last decade, our knowledge on the clinical pharmacokinetic of colistin has increased considerably. Several studies have pointed out that intravenous administration of colistimethate sodium (CMS) may lead to suboptimal plasma concentrations and is associated with higher mortality. Thus, low daily dosage of i.v. colistin has been identified as an independent predictor of mortality (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.68-0.96) in patients with VAP [21]. In 13 critically ill patients with VAP caused by GNB, colistin was undetectable in BAL performed at 2 h after the start of the CMS infusion (2 million IU 8-hourly) [22].

The need for a loading dose and the administration of high doses of colistin has been recently demonstrated. Plachouras et al [23] described in 18 critically ill patients receiving 3 million IU of CMS 8-hourly that plasma colistin concentrations were sub-optimal for 2-3 days before reaching steady state. The authors recommended a loading dose of 9 million IU and 4.5 million IU 12-hourly because colistin displayed a half-life that was significantly long in relation to the dosing interval. The clinical efficacy and the lack of toxicity of this regimen have been confirmed in a series of critically ill patients with bacteremia or VAP caused by MDR-GNB [24]. In contrast, a loading dose of 6 MU may be adequate [25], and our preliminary results indicate that a loading dose of 4.5 UI of colistin may be sufficient to reach therapeutic levels in non-obese critically ill patients with MDR-VAP [26].

The efficacy of colistin in VAP caused by MDR-GNB has been demonstrated in several retrospective and prospective series [27–30]. These studies have evaluated colistin mostly in the directed therapy being scarce the information about the use of this antibiotic empirically. A multicenter randomized clinical trial (RCT) that is currently ongoing has been designed to assess the efficacy and safety of colistin compared to meropenem in the empirical therapy of VAP with high suspicion of MDR-GNB [31]. While awaiting the results of this RCT, the empirical use of colistin may justify in institutions where there is a high rate of infections due to MDR-GNB [32].

Synergistic activity of colistin and rifampicin combination against different GNB has been documented in experimental models [33, 34]. Nevertheless, a recent RCT failed to demonstrate clinical superiority of the combination of colistin plus rifampicin over monotherapy with colistin in patients with severe infections (two-thirds with VAP) caused by extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii[35]. The results were identical in another clinical trial that compared colistin plus rifampicin with colistin in patients with VAP caused by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii[36].

Different in vitro studies have documented the existence of a potent synergism of the combination of colistin with a glycopeptide against carbapenem-resistant A baumannii[37, 38]. In a retrospective series, we did not find clinical benefit of this combination in patients with A baumannii VAP and observed a higher rate of renal failure in comparison with monotherapy with colistin [39]. Conversely, a multicenter study that included a heterogeneous group of infections caused by different GNBs concluded that therapy with colistin plus a glycopeptide ≥ 5 days was a protective factor for 30-day mortality [40].

Tigecycline

Tigecycline is a broad spectrum antibiotic with potent in vitro activity against anaerobic and aerobic Gram-positive bacteria and Gram-negative pathogens with the exceptions of P aeruginosa and Proteus ssp. Tigecycline is active against A. baumannii, including some colistin-resistant strains [41].

Notwithstanding, tigecycline is not licensed for treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia, including VAP. In a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, study that compared 50 mg every 12 h (loading dose 100 mg) with imipenem, tigecycline was inferior to the imipenem/cilastatin regimen for the clinically evaluable population. This difference appeared to have been caused by results in VAP patients in whom there was a higher mortality in the tigecycline group that did not reach statistical significance [42]. Nevertheless, small series and observational studies have reported acceptable results with the use of tigecycline for MDR-VAP [43, 44]. Very recently, in a matched cohort analysis adjusted for propensity score, episodes of A baumannii VAP treated with tigecycline had a statistically significant excess of mortality in comparison to patients treated with colistin. The excess mortality of tigecycline was significant only among those with MIC >2 μg/mL, but not for those with MIC ≦ 2 μg/mL. All isolates were susceptible to colistin [45].

Dose of tigeclycline approved for intra-abdominal and skin and soft tissue infections (50 mg every 12 h with a loading dose of 100 mg) does not achieve adequate concentrations for pulmonary infections [46]. A recent randomized phase 2 trial has evaluated the clinical efficacy of two high-dosage tigecycline regimens versus imipenem-cilastatin for treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Although the number of patients included is too low to draw conclusions in terms of mortality, 200 mg followed by 100 mg every 12 h achieved the greatest rate of clinical cure [47]. Therefore, it seems necessary to administer, in an episode with suspicion of extremely resistant GNB, this high dose in order to avoid insufficient levels in lung tissue and, at least empirically, always in combination therapy (a carbapenem or colistin are probably the best options).

Fosfomycin

Fosfomycin is an “old” antimicrobial that shows potent bactericidal action against many Gram-negative and Gram-positive pathogens. The drug shows little toxicity. Regrettably, resistance develops rapidly when fosfomycin is used as monotherapy. Since fosfomycin shows synergistic action with other antimicrobials it is an interesting option to treat a wide range of infections, including VAP caused by MDR pathogens [48].

This antibiotic has gained recently relevance for the treatment of extensively resistant GNB especially K pneumonia or P aeruginosa due to the lack of valid alternatives. A recent series has reported an acceptable response in patients with VAP treated with high doses (24 g/day) of fosfomycin always in combination with other antimicrobials [49].

Antibiotics for resistant Gram-positive cocci

Empirical coverage of MRSA is less troublesome. Vancomycin has been considered the treatment of choice for pneumonia due to MRSA [4]. Almost all MRSA isolates are susceptible to vancomycin and only anecdotal cases of MRSA resistant to this glycopeptide have been reported. However, an interesting issue to keep in mind is the MIC of MRSA to vancomycin. Several studies in patients with MRSA pneumonia or bacteremia (mainly from lung source) have observed a higher rate of treatment failure and mortality in episodes with MIC ≥ 1.5 mg/L treated with vancomycin [50, 51]. Lung infection has been identified as an independent predictor of treatment failure in MRSA bacteremia treated with vancomycin and not explained by MIC [52], perhaps reflecting the poor penetration of this antibiotic into the lung tissue [53].

Current guidelines recommend a loading dose of 25-30 mg/kg followed by vancomycin dosages of 15-20 mg/kg given every 8-12 hours for patients with normal renal function [54]. Monitoring of trough concentrations is necessary after the forth dose to maintain serum trough concentrations of 15-20 mg/L increase efficacy and improve clinical outcomes. An AUC to MIC ratio ≥400 has been shown to predict more favorable microbiological and clinical outcomes in cases of S. aureus pneumonia [55].

Teicoplanin might be an acceptable alternative to treat pneumonia caused by MRSA. However, the administration of high teicoplanin doses (12 mg/kg teicoplanin every 12 h the first 2 days followed by 12 mg/kg once daily) is needed to reach sufficient antibiotic concentrations in lung tissues at steady state [56]. We do not recommend teicoplanin for VAP due to the uncertainties about the correct doses, impossibility of level measurements, and the availability of alternatives such as vancomycin or linezolid.

Linezolid has been shown to have a better pharmacokinetic profile than vancomycin [57]. The post hoc analysis of two randomized, double-blind studies concluded that linezolid therapy was associated with significantly better clinical cure and survival rates than therapy with vancomycin in the subgroup of patients with MRSA VAP [58]. In a recent double-blind, controlled trial, linezolid, compared with vancomycin, achieved a higher clinical and microbiological response rate (the latter was not statistically significant) despite vancomycin dose optimization, together with a lower incidence of all types of renal adverse effects in patients with MRSA pneumonia. However, mortality was unaffected [59]. Limitations of this study include imbalanced distribution of medical comorbidities and the number of patients excluded to reach the per-protocol group.

Although tigecycline is active against MRSA, clinical cure of cases of MRSA was lower with tigecycline than with the comparator in the clinical trial that evaluated this antibiotic in hospital-acquired pneumonia [42]. Therefore, we do not advocate the use of tigecycline for MRSA pneumonia and a specific antibiotic against this Gram-positive bacterium is necessary.

Ceftaroline is a cephalosporin with broad gram-positive activity, including MRSA. Its gram-negative activity includes common respiratory pathogens and members of the Enterobacteriaceae. However, ceftaroline is currently only approved for acute bacterial skin infections and community-acquired pneumonia. This new cephalosporin has a promising role in the treatment of VAP but clinical data are not currently available. It should be used in combination with another antimicrobial to cover GNB such as P aeruginosa or ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae.

Nebulized antibiotics

The administration of nebulized antibiotics has been proposed to provide high levels of the drug in the lung and to reduce the systemic toxicity associated with intravenous antibiotics. The concentration in the respiratory secretion of the nebulized antibiotic may be 20 to 100 fold greater than the in-vitro MIC of the organisms being treated [60]. Large randomized trials are needed to define the impact on clinical outcomes of nebulized antibiotics as adjunctive therapy in MDR-VAP.

Although diverse antibiotics have been nebulized, the most extensive experience exists with aminoglycosides and colistin. The use of appropriate devices is essential to assure clinical and microbiological utility of nebulized antibiotics. During mechanical ventilation, high amounts of the particles dispersed by conventional nebulizers remain in the ventilatory circuits and the tracheobronchial tree and, therefore, less drug is available in the alveolar compartment.

The use of aerosolized colistin for multi-drug resistant GNB pneumonia increases cure rates and may be reasonably efficacious and safe [61]. The use of inhaled colistin was independently associated with clinical cure in a retrospective study (OR 2.53, 95% CI 1.11-5.76) although mortality was unaffected. Nevertheless, other studies have concluded that the use of aerosolized colistin in conjunction with intravenous colistin did not provide additional therapeutic benefit to patients with MDR VAP due to gram-negative bacteria [62]. Moreover, a randomized controlled trial of nebulized CMS as adjunctive therapy of ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by GNB failed to demonstrate beneficial effect on clinical outcome [63]. Regarding aminoglycosides, several studies have evaluated tobramycin or amikacin with promising results [64, 65].

Duration of treatment

There is no consensus regarding the duration of antibiotic treatment for patients with VAP due to MDR. In a randomized clinical trial that included patients with VAP and adequate empirical antimicrobial therapy, short-course (8 days) treatment of VAP has no difference in terms of mortality compared to long-course (15 days) treatment. In VAP caused by non-fermenting gram-negative bacilli including P aeruginosa, rate of recurrence was significantly higher (40.6% vs 25.4%) in patients receiving 8 days of treatment [66]. A recent meta-analysis of four RCTs also concluded that a short-course of antibiotic may be enough to treat VAP although the issue of length of therapy in MDR VAP has not been specifically evaluated [67]. A prospective study showed that a procalcitonin-based strategy (recommending that physicians stop antibiotics when the procalcitonin concentration was <0.5 ng/mL, or had decreased by ≥80%) did not negatively influence outcomes although the subgroup of patients with MDR-VAP was not specifically assessed [68].

Conclusions

Empirical treatment of a VAP with a high probability of a MDR pathogen is one of the major challenges facing an intensivist. Similarly, it is complex the directed therapy especially when a very-difficult-to-treat MDR-GNB (i.e. carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae, extremely drug-resistant A baumannii or P aeruginosa) is confirmed as the etiology of the pneumonia. Our personal point of view for the treatment of VAP caused by MDR pathogens is summarized as a Decalogue in Table 1. Doses of antibiotics recommended for these infections are depicted in Table 2.

References

Bercault N, Boulain T: Mortality rate attributable to ventilator-associated nosocomial pneumonia in an adult intensive care unit: a prospective case-control study. Crit Care Med. 2001, 29: 2303-2309.

Vallés J, Pobo A, García-Esquirol O, Mariscal D, Real J, Fernández R: Excess ICU mortality attributable to ventilator-associated pneumonia: the role of early vs late onset. Intensive Care Med. 2007, 33: 1363-1368.

Trouillet JL, Chastre J, Vuagnat A, Joly-Guillou ML, Combaux D, Dombert MC, Gibert C: Ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by potentially drug-resistant bacteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998, 157: 531-539.

Chastre J, Fagon JY: Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002, 165: 867-903.

Garnacho-Montero J, Ortiz-Leyba C, Fernández-Hinojosa E, Aldabó-Pallás T, Cayuela A, Marquez-Vácaro JA, Garcia-Curiel A, Jiménez-Jiménez FJ: Acinetobacter baumannii ventilator-associated pneumonia: epidemiological and clinical findings. Intensive Care Med. 2005, 31: 649-655.

Giantsou E, Liratzopoulos N, Efraimidou E, Panopoulou M, Alepopoulou E, Kartali-Ktenidou S, Minopoulos GI, Zakynthinos S, Manolas KI: Both early-onset and late-onset ventilator-associated pneumonia are caused mainly by potentially multiresistant bacteria. Intensive Care Med. 2005, 31: 1488-1494.

Martin-Loeches I, Deja M, Koulenti D, Dimopoulos G, Marsh B, Torres A, Niederman MS, Rello J, EU-VAP Study Investigators: Potentially resistant microorganisms in intubated patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia: the interaction of ecology, shock and risk factors. Intensive Care Med. 2013, 39: 672-681.

Koulenti D, Lisboa T, Brun-Buisson C, Krueger W, Macor A, Sole-Violan J, Diaz E, Topeli A, DeWaele J, Carneiro A, Martin-Loeches I, Armaganidis A, Rello J, EU-VAP/CAP Study Group: Spectrum of practice in the diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia in patients requiring mechanical ventilation in European intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2009, 37: 2360-2368.

Canadian Critical Care Trials Group: A randomized trial of diagnostic techniques for ventilator-associated pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2006, 355: 2619-2630.

Chastre J: Conference summary: ventilator-associated pneumonia. Respir Care. 2005, 50: 975-983.

American Thoracic Society: Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005, 171: 388-416.

Papp-Wallace KM, Endimiani A, Taracila MA, Bonomo RA: Carbapenems: past, present, and future. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011, 55: 4943-4960.

Chastre J, Wunderink R, Prokocimer P, Lee M, Kaniga K, Friedland I: Efficacy and safety of intravenous infusion of doripenem versus imipenem in ventilator-associated pneumonia: a multicenter, randomized study. Crit Care Med. 2008, 36: 1089-1096.

Kollef MH, Chastre J, Clavel M, Restrepo MI, Michiels B, Kaniga K, Cirillo I, Kimko H, Redman R: A randomized trial of 7-day doripenem versus 10-day imipenem-cilastatin for ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care. 2012, 16 (6): R218-

Luyt CE, Aubry A, Lu Q, Micaelo M, Bréchot N, Brossier F, Brisson H, Rouby JJ, Trouillet JL, Combes A, Jarlier V, Chastre J: Imipenem, meropenem or doripenem to treat patients with pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014, 58: 1372-1380.

Roberts JA, Kirkpatrick CM, Roberts MS, Robertson TA, Dalley AJ, Lipman J: Meropenem dosing in critically ill patients with sepsis and without renal dysfunction: intermittent bolus versus continuous administration? Monte Carlo dosing simulations and subcutaneous tissue distribution. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009, 64: 142-150.

Lorente L, Lorenzo L, Martín MM, Jiménez A, Mora ML: Meropenem by continuous versus intermittent infusion in ventilator-associated pneumonia due to gram-negative bacilli. Ann Pharmacother. 2006, 40: 219-223.

Bulik CC, Nicolau DP: Double-carbapenem therapy for carbapenemase- producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011, 55: 3002-3004.

Ceccarelli G, Falcone M, Giordano A, Mezzatesta ML, Caio C, Stefani S, Venditti M: Successful ertapenem-doripenem combination treatment of bacteremic ventilator-associated pneumonia due to colistin-resistant KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013, 57: 2900-2901.

Li J, Nation RL, Milne RW, Turnidge JD, Coulthard K: Evaluation of colistin as an agent against multi-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2005, 25: 11-25.

Korbila IP, Michalopoulos A, Rafailidis PI, Nikita D, Samonis G, Falagas ME: Inhaled colistin as adjunctive therapy to intravenous colistin for the treatment of microbiologically documented ventilator-associated pneumonia: a comparative cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010, 16: 1230-1236.

Imberti R, Cusato M, Villani P, Carnevale L, Iotti GA, Langer M, Regazzi M: Steady-state pharmacokinetics and bronchoalveolar lavage concentration of colistin in critically ill patients after intravenous colistin methanesulfonate administration. Chest. 2010, 138: 1333-1339.

Plachouras D, Karvanen M, Friberg LE, Papadomichelakis E, Antoniadou A, Tsangaris I, Karaiskos I, Poulakou G, Kontopidou F, Armaganidis A, Cars O, Giamarellou H: Population pharmacokinetic analysis of colistin methanesulphonate and colistin after intravenous administration in critically ill patients with Gram-negative bacterial infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009, 53: 3430-3436.

Dalfino L, Puntillo F, Mosca A, Monno R, Spada ML, Coppolecchia S, Miragliotta G, Bruno F, Brienza N: High-dose, extended-interval colistin administration in critically ill patients: is this the right dosing strategy? A preliminary study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012, 54: 1720-1726.

Mohamed AF, Karaiskos I, Plachouras D, Karvanen M, Pontikis K, Jansson B, Papadomichelakis E, Antoniadou A, Giamarellou H, Armaganidis A, Cars O, Friberg LE: Application of a loading dose of colistin methanesulfonate in critically ill patients: population pharmacokinetics, protein binding, and prediction of bacterial kill. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012, 56: 4241-4249.

Pachón-Ibañez , Doboco F, Gutiérrez-Valencia A, Puppo-Moreno A, Gutiérrez-Pizarraya A, Ruiz-Valderas R, Fernández-Hinojosa E, Milara C, Leal-Noval SR, Moreno-Martínez P, Amaya R, Rosso C, López-Cortes L, Cisneros JM, Garnacho-Montero J: Pharmacokinetics of colistin after the administration of a loading dose of 4.5 mu of colistin methanesulfonate (CMS) in obese critically ill patients versus regular weight critically ill patients. Intensive care Med. 2013, 39 (suppl 2): S433-

Levin AS, Barone AA, Penço J, Santos MV, Marinho IS, Arruda EA, Manrique EI, Costa SF: Intravenous colistin as therapy for nosocomial infections caused by multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin Infect Dis. 1999, 28: 1008-1111.

Garnacho-Montero J, Ortiz-Leyba C, Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, Barrero-Almodóvar AE, García-Garmendia JL, Bernabeu-WittelI M, Gallego-Lara SL, Madrazo-Osuna J: Treatment of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) with intravenous colistin: a comparison with imipenem-susceptible VAP. Clin Infect Dis. 2003, 36: 1111-1118.

Reina R, Estenssoro E, Sáenz G, Canales HS, Gonzalvo R, Vidal G, Martins G, Das Neves A, Santander O, Ramos C: Safety and efficacy of colistin in Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas infections: a prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2005, 31: 1058-1065.

Kallel H, Hergafi L, Bahloul M, Hakim A, Dammak H, Chelly H, Hamida CB, Chaari A, Rekik N, Bouaziz M: Safety and efficacy of colistin compared with imipenem in the treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a matched case-control study. Intensive Care Med. 2007, 33: 1162-1167.

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01292031?term=colistin+and+VAP&rank=2. Accessed 20 March 2014

Kollef MH: An empirical approach to the treatment of multidrug-resistant ventilator-associated pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2003, 36: 1119-1121.

Pachón-Ibáñez ME, Docobo-Pérez F, López-Rojas R, Domínguez-Herrera J, Jiménez-Mejias ME, García-Curiel A, Pichardo C, Jiménez L, Pachón J: Efficacy of rifampin and its combinations with imipenem, sulbactam, and colistin in experimental models of infection caused by imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010, 54: 1165-1172.

Tascini C, Tagliaferri E, Giani T, Leonildi A, Flammini S, Casini B, Lewis R, Ferranti S, Rossolini GM, Menichetti F: Synergistic activity of colistin plus rifampin against colistin-resistant KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013, 57: 3990-3993.

Durante-Mangoni E, Signoriello G, Andini R, Mattei A, De Cristoforo M, Murino P, Bassetti M, Malacarne P, Petrosillo N, Galdieri N, Mocavero P, Corcione A, Viscoli C, Zarrilli R, Gallo C, Utili R: Colistin and rifampicin compared with colistin alone for the treatment of serious infections due to extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: a multicenter, randomized clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2013, 57: 349-358.

Aydemir H, Akduman D, Piskin N, Comert F, Horuz E, Terzi A, Kokturk F, Ornek T, Celebi G: Colistin vs. the combination of colistin and rifampicin for the treatment of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ventilator-associated pneumonia. Epidemiol Infect. 2013, 141: 1214-1222.

Gordon NC, Png K, Wareham DW: Potent synergy and sustained bactericidal activity of a vancomycin-colistin combination versus multidrug-resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010, 54: 5316-5322.

Wareham DW, Gordon NC, Hornsey M: In vitro activity of teicoplanin combined with colistin versus multidrug-resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011, 66: 1047-1051.

Garnacho-Montero J, Amaya-Villar R, Gutiérrez-Pizarraya A, Espejo-Gutiérrez de Tena E, Artero-González ML, Corcia-Palomo Y, Bautista-Paloma J: Clinical efficacy and safety of the combination of colistin plus vancomycin for the treatment of severe infections caused by carbapenem-resistant. A baumannii Chemotherapy. 2013, 59: 225-231.

Petrosillo N, Giannella M, Antonelli M, Antonini M, Barsic B, Belancic L, Inkaya AC, De Pascale G, Grilli E, Tumbarello M, Akova M: Colistin-glycopeptide combination in critically ill patients with Gram negative infection: the clinical experience. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014, 58: 851-858.

Arroyo LA, Mateos I, González V, Aznar J: In vitro activities of tigecycline, minocycline, and colistin-tigecycline combination against multi- and pandrug-resistant clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii group. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009, 53: 1295-1296.

Freire AT, Melnyk V, Kim MJ, Datsenko O, Dzyublik O, Glumcher F, Chuang YC, Maroko RT, Dukart G, Cooper CA, Korth-Bradley JM, Dartois N, Gandjini H, 311 Study Group: Comparison of tigecycline with imipenem/cilastatin for the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010, 68: 140-151.

Curcio D, Fernández F, Vergara J, Vazquez W, Luna CM: Late onset ventilator-associated pneumonia due to multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter spp.: experience with tigecycline. J Chemother. 2009, 21: 58-62.

Conde-Estévez D, Grau S, Horcajada JP, Luque S: Off-label prescription of tigecycline: clinical and microbiological characteristics and outcomes. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010, 36: 471-472.

Chuang YC, Cheng CY, Sheng WH, Sun HY, Wang JT, Chen YC, Chang SC: Effectiveness of tigecycline-based versus colistin- based therapy for treatment of pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant acinetobacter baumannii in a critical setting: a matched cohort analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2014, 14: 102-

Burkhardt O, Rauch K, Kaever V, Hadem J, Kielstein JT, Welte T: Tigecycline possibly underdosed for the treatment of pneumonia: a pharmacokinetic viewpoint. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009, 34: 101-102.

Ramirez J, Dartois N, Gandjini H, Yan JL, Korth-Bradley J, McGovern PC: Randomized phase 2 trial to evaluate the clinical efficacy of two high-dosage tigecycline regimens versus imipenem-cilastatin for treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013, 57: 1756-1762.

Falagas ME, Kastoris AC, Kapaskelis AM, Karageorgopoulos DE: Fosfomycin for the treatment of multidrug-resistant, including extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing, enterobacteriaceae infections: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010, 10: 43-50.

Pontikis K, Karaiskos I, Bastani S, Dimopoulos G, Kalogirou M, Katsiari M, Oikonomou A, Poulakou G, Roilides E, Giamarellou H: Outcomes of critically ill intensive care unit patients treated with fosfomycin for infections due to pandrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014, 43: 52-59.

Choi EY, Huh JW, Lim CM, Koh Y, Kim SH, Choi SH, Kim YS, Kim MN, Hong SB: Relationship between the MIC of vancomycin and clinical outcome in patients with MRSA nosocomial pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2011, 37: 639-647.

Haque NZ, Zuniga LC, Peyrani P, Reyes K, Lamerato L, Moore CL, Patel S, Allen M, Peterson E, Wiemken T, Cano E, Mangino JE, Kett DH, Ramirez JA, Zervos MJ: Relationship of vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration to mortality in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, or health-care-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2010, 138: 1356-1362.

Walraven CJ, North MS, Marr-Lyon L, Deming P, Sakoulas G, Mercier RC: Site of infection rather than vancomycin MIC predicts vancomycin treatment failure in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011, 66: 2386-2392.

Lodise TP, Drusano GL, Butterfield JM, Scoville J, Gotfried M, Rodvold KA: Penetration of vancomycin into epithelial lining fluid in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011, 55: 5507-5511.

Rybak M, Lomaestro B, Rotschafer JC, Moellering R, Craig W, Billeter M, Dalovisio JR, Levine DP: Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin in adult patients: a consensus review of the American society of health-system pharmacists, the infectious diseases society of America, and the society of infectious diseases pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009, 66: 82-98.

Moise-Broder PA, Forrest A, Birmingham MC, Schentag JJ: Pharmacodynamics of vancomycin and other antimicrobials in patients with Staphylococcus aureus lower respiratory tract infections. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004, 43: 925-942.

Mimoz O, Rolland D, Adoun M, Marchand S, Breilh D, Brumpt I, Debaene B, Couet W: Steady-state trough serum and epithelial lining fluid concentrations of teicoplanin 12 mg/kg per day in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2006, 32: 775-779.

Boselli E, Breilh D, Rimmelé T, Djabarouti S, Toutain J, Chassard D, Saux MC, Allaouchiche B: Pharmacokinetics and intrapulmonary concentrations of linezolid administered to critically ill patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2005, 33: 1529-1533.

Kollef MH, Rello J, Cammarata SK, Croos-Dabrera RV, Wunderink RG: Clinical cure and survival in Gram-positive ventilator-associated pneumonia: retrospective analysis of two double-blind studies comparing linezolid with vancomycin. Intensive Care Med. 2004, 30: 388-394.

Wunderink RG, Niederman MS, Kollef MH, Shorr AF, Kunkel MJ, Baruch A, McGee WT, Reisman A, Chastre J: Linezolid in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia: a randomized, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012, 54: 621-629.

Palmer LB: Aerosolized antibiotics in critically ill ventilated patients. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009, 15: 413-418.

Michalopoulos A, Fotakis D, Virtzili S, Vletsas C, Raftopoulou S, Mastora Z, Falagas ME: Aerosolized colistin as adjunctive treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia due to multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: a prospective study. Respir Med. 2008, 102: 407-412.

Kofteridis DP, Alexopoulou C, Valachis A, Maraki S, Dimopoulou D, Georgopoulos D, Samonis G: Aerosolized plus intravenous colistin versus intravenous colistin alone for the treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a matched case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2010, 51: 1238-1244.

Rattanaumpawan P, Lorsutthitham J, Ungprasert P, Angkasekwinai N, Thamlikitkul V: Randomized controlled trial of nebulized colistimethate sodium as adjunctive therapy of ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by Gram-negative bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010, 65: 2645-2649.

Hallal A, Cohn SM, Namias N, Habib F, Baracco G, Manning RJ, Crookes B, Schulman CI: Aerosolized tobramycin in the treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a pilot study. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2007, 8: 73-82.

Niederman MS, Chastre J, Corkery K, Fink JB, Luyt CE, García MS: BAY41-6551 achieves bactericidal tracheal aspirate amikacin concentrations in mechanically ventilated patients with Gram-negative pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2012, 38: 263-271.

Chastre J, Wolff M, Fagon JY, Chevret S, Thomas F, Wermert D, Clementi E, Gonzalez J, Jusserand D, Asfar P, Perrin D, Fieux F, Aubas S: Comparison of 8 vs 15 days of antibiotic therapy for ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003, 290: 2588-2598.

Dimopoulos G, Poulakou G, Pneumatikos IA, Armaganidis A, Kollef MH, Matthaiou DK: Short- vs long-duration antibiotic regimens for ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2013, 144: 1759-1767.

Stolz D, Smyrnios N, Eggimann P, Pargger H, Thakkar N, Siegemund M, Marsch S, Azzola A, Rakic J, Mueller B, Tamm M: Procalcitonin for reduced antibiotic exposure in ventilator-associated pneumonia: a randomised study. Eur Respir J. 2009, 34: 1364-1375.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/14/135/prepub

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

JGM has received speaking fee from Pfizer. The rest of the authors do not report potential conflicts of interests.

Authors’ contributions

YCP, RAV, and LMV performed the literature search. JGM wrote the first draft. All the authors discussed this draft and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Garnacho-Montero, J., Corcia-Palomo, Y., Amaya-Villar, R. et al. How to treat VAP due to MDR pathogens in ICU patients. BMC Infect Dis 14, 135 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-135

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-135