Abstract

Background

Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) are the current complement to microscopy for ensuring prompt malaria treatment. We determined the performance of three candidate RDTs (Paracheck™-Pf, SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf and SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf/pan) for rapid diagnosis of malaria in the Central African Republic.

Methods

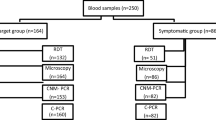

Blood samples from consecutive febrile patients who attended for laboratory analysis of malaria at the three main health centres of Bangui were screened by microscopy and the RDTs. Two reference standards were used to assess the performance of the RDTs: microscopy and, a combination of microscopy plus nested PCR for slides reported as negative, on the assumption that negative results by microscopy were due to sub-patent parasitaemia.

Results

We analysed 436 samples. Using the combined reference standard of microscopy + PCR, the sensitivity of Paracheck™-Pf was 85.7% (95% CI, 80.8–89.8%), that of SD Bioline Ag-Pf was 85.4% (95% CI, 80.5–90.7%), and that of SD Bioline Ag-Pf/pan was 88.2% (95% CI, 83.2–92.0%). The tests performed less well in cases of low parasitaemia; however, the sensitivity was > 95% at > 500 parasites/μl.

Conclusions

Overall, SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf and SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf/pan performed slightly better than Paracheck™-Pf. Use of RDTs with reinforced microscopy practice and laboratory quality assurance should improve malaria treatment in the Central African Republic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In countries in sub-Saharan Africa, malaria management is frequently based on clinical criteria, leading to overuse of antimalarial agents [1, 2]. After the 1990s, a rapid increase in resistance to first-line therapy was observed, with a consequent decrease in the efficacy of chloroquine [3] and its replacement by sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine [4, 5]. Subsequently, effective but more expensive artemisinin combination treatments were introduced for first-line treatment [6]. These new therapies should be targeted in order to avoid overuse of antimalarial drugs, which can lead to the selection of drug-resistant parasites [7].

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends parasitological confirmation for all patients suspected of having malaria before starting treatment. This recommendation includes high-quality microscopy or, when that is not available, use of easy-to-use rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) [8]. Panel studies have been conducted to compare the performance of commercially available RDTs [9]. Although these studies provide selection criteria, field evaluations are essential to obtain operational data [10–15], as the heterogeneous performance of these tests depends on local factors, such as deletions or mutations in the PfHRP-2 gene [16–21], the prozone effect [22], cross-reactivity with human autoantibodies [23, 24] and the presence of other infectious diseases [25]. Local data are therefore required to select suitable RDTs before they are used [16, 26–28].

A recent multi-centre study assessing global sequence variation in PfHRP-2 and −3 found wide variation in PfHRP-2 sequences in samples from the Central African Republic. The authors speculated that this might reduce the sensitivity of RDTs for detecting malaria in people with very low parasite density [29]. In this country, the quality of microscopy in the public health sector is poor, and presumptive treatment of malaria is still widespread [30]. The Ministry of Health has selected the RDTs Paracheck™-Pf, SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf and SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf/pan as candidates on the basis of panel studies [9]. The objective of the study reported here was to evaluate the performance of these tests in the field.

Methods

Study area and design

This cross-sectional study was conducted in August 2011 in Bangui, capital of the Central African Republic, in the Hospital de l’Amitié, the Complexe Pediatrique and the Institut Pasteur of Bangui. Bangui is located beside the Oubangui River, north of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (geographical coordinates 7.00 N, 21.00 E). The climate is tropical, and rainfall peaks between April and November. The average temperature varies from 19°C to 32°C. The main malaria parasite is Plasmodium falciparum, and malaria transmission occurs throughout the year, with peaks at the beginning and the end of the rainy season, although no data are available on the intensity of transmission. Malaria accounts for more than 40% of morbidity in the country (Central African Republic Ministry of Health, 2010 annual report, unpublished data).

The Hospital de l’Amitié and the Complexe Pédiatrique are tertiary referral public health centres equipped with laboratories where thin and thick smears are analysed. The Institut Pasteur of Bangui is a private centre (International Network of Instituts Pasteur) for biomedical research, in which laboratory diagnosis for malaria is performed for patients referred by clinicians at health centres where this test is not available.

We analysed the performance of three RDTs: Paracheck™-Pf, SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf and SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf and /pan (Standard Diagnostics Ref 05FK60, Inc; Suwon City, Republic of Korea). SD Bioline Malaria Ag Pf and Paracheck™-Pf contain antibodies against P. falciparum-specific histidine-rich protein type 2 (PfHRP2), while Bioline Malaria Ag Pf/Pan contains antibodies targeting both PfHRP2 and lactate dehydrogenase specific to P. falciparum and other Plasmodium species (P. vivax, P. ovale and P. malariae). Blood samples from people attending each study centre for laboratory analysis were tested for the presence or absence of malaria parasites by microscopy and the RDTs. Samples from patients with negative microscopy (regardless of RDT result) were tested P. falciparum by nested PCR, on the assumption that false-positive results with RDTs are due to sub-patent parasitaemia [31].

Patient recruitment

Consecutive patients of all ages presenting at each study site were approached by the study technician for recruitment. Each patient’s medical card was checked, and those with a request for smear analysis were considered eligible if they were febrile (axillary temperature ≥ 37.5°C) or had a history of fever in the previous 24 h. They were included in the study if they gave written consent; for patients aged ≤ 18 years, informed consent was provided by a parent or guardian.

Ethical approval

This project was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of the University of Bangui. The Central African Republic Health Ministry also gave approval for this study.

Sample size estimation

For an estimated annual malaria rate in Bangui of 40% (Central African Republic Ministry of Health, 2010 annual report, unpublished data), an expected sensitivity of Bioline RDTs of 95% [26] and a sensitivity set at ± 2.5%, a sample size of 421 patients was estimated.

Selection of technicians

In each study centre, the laboratory team consisted of three technicians with university training, all of whom had been re-trained for diagnosing malaria in the laboratory by standard operational procedures [32]. The technicians were also trained to perform and read the Paracheck™-Pf, SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf and SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf and /pan tests. At the Institut Pasteur, a fourth laboratory technician was designated to analyse all discrepant slides and to perform PCR.

Malaria diagnosis

Finger-prick blood samples were obtained for slides and for testing with the RDTs. Blood smears were air-dried, stained with 4% Giemsa and analysed under a light microscope (× 100 oil immersion) to detect asexual forms of P. falciparum. Parasite density was determined as the number of parasites per 200 leukocytes on the assumption of an average leukocyte count of 8000/μl of blood. A result was considered negative if no parasites were detected per 200 leukocytes. Each slide was read independently by two study technicians. In the case of a discrepant qualitative result (negative or positive), a third reading was done by the designated technician at the Institut Pasteur. All the laboratory technicians were blinded to the RDT results. The results of both microscopy and the RDTs were reported to the clinicians, who were advised to treat the patient for malaria if the results of these two analyses were discrepant.

The RDTs were performed by the third technician at the study centre following the manufacturer’s instructions.

For patients with negative microscopy, three drops of blood were collected on a piece of filter paper (Whatman®). The blood spots were air-dried and stored at 4°C in individual sterile plastic bags for PCR analysis.

Parasite DNA extraction and PCR assays were performed at the Institut Pasteur. The blood-impregnated filter paper piece was washed with distilled water and placed directly in a PCR tube containing the PCR reaction components. Genomic DNA was determined in an assay based on nested PCR for Plasmodium DNA [33].

Statistical analysis

Data were entered onto Excel spreadsheets and analysed with MedCalc®software (MedCalc Software, Acacialaan 22, B-8400 Ostend, Belgium).

The first step of our analysis was to determine the performance of the RDTs according to the falciparum density in samples found positive by microscopy. Density was categorized as ≤ 100, 101–200, 201–500, 501–1000, 1001–5000, 5001–50 000 and > 50 000 parasites/μl. RDT results were compared (paired proportions) with the McNemar test, at a level of significance (P) of 0.05.

The second step was to estimate the performance of the RDTs against the combined results of microscopy and nested PCR, expressed as true-positive (TP), true-negative (TN), false-positive (FP) or false negative (FN). The formulas used to calculate performance were TP/TP + FN for sensitivity, TN/TN + FP for specificity, TP/TP + FP for positive predictive value (PPV) and TN/TN + FN for negative predictive value (NPV). The results were interpreted with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). At baseline, the results of the comparison between the RDTs and microscopy were expressed as TP1, TN1, FP1 or FN1. Then, the analysis took onto account the results of PCR performed on samples that were negative by microscopy (classified as FP1 or TN1 in the RDTs). According to the PCR results, the results of the RDTs were designated as TP2 if PCR was positive in FP1, FP2 if PCR was negative in FP1, FN2 if PCR was positive in TN1 and TN2 if PCR was negative in TN1. Combination of the results of the RDTs for samples positive by microscopy and of PCR for samples negative by microscopy gave the values TP = TP1 + TP2, TN = TN2, FP = FP2 and FN = FN1 + FN2, which were used to calculate the performance of the RDTs.

Results

A total of 437 patients were recruited for this study between 8 and 22 August 2011. Microscopic analysis showed that 53.8% (235/437) of the blood slides were positive for P. falciparum. In 234/235 (99.6%) cases of infection, P. falciparum was the only parasite species identified. One infected individual had a P. ovale mono-infection (detected by SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf/pan and confirmed by nested PCR) and was hence excluded from the study, which was confined to detection of falciparum malaria.

The RDTs gave positive results in 52.3% (228/436) of cases with Paracheck™-Pf, 57.8% (252/436) with SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf and 58.0% (253/436) with SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf/pan.

Comparison of the results of the RDTs with those of microscopy showed concordant positive results in 85.9% (201/234) of cases with Paracheck™-Pf, 92.3% (216/234) with SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf and 92.3% (216/234) with SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf/pan. Of the samples that were negative by microscopy, 13.4% (27/202) were found to be positive with Paracheck™-Pf, 17.8% (36/202) with SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf and 18.8% (38/202) with SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf/pan.

The proportion of positive results with each of the RDTs increased with parasitaemia. For a parasitaemia ≤ 100 parasites/μl, the proportions were 56.5% with Paracheck™-Pf and 69.6% with SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf and SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf/pan. For a parasitaemia < 501 parasites/μl, the proportion of positive results with Paracheck™-Pf was significantly lower than with the Bioline kits (p = 0.04) (Figure 1). The sensitivity of the RDTs correlated positively with parasitaemia, with values < 70% when the parasitaemia was < 100 parasites/μl. The sensitivity of the SD Bioline devices increased to > 80% when the parasitaemia was 101–200 parasites/μl, whereas the sensitivity of Paracheck™-Pf remained at 63.4%. The sensitivity of all three tests increased substantially (> 95%) at parasite counts > 500 parasites/μl (Table 1). Negative results were found with all three RDTs in 18 blood samples with parasitaemia ranging from 40 to 400 parasites/μl.

PCR assays detected 11 false-negative results (11/202 or 5.4%) by microscopy and 7 false-negative results (7/202 or 4.2%) by both microscopy and the RDTs. Overall, the combined results of microscopy and PCR showed a sensitivity of 85.7% for Paracheck™-Pf, 85.4% for SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf and 88.2% for SD Bioline Ag-Pf/Pan. The specificity was 86.0% for Paracheck™-Pf, 86.3% for SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf and 80.4% for SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf/pan.

The overall sensitivities, specificities, NPV and PPV for the three RDTs, evaluated against microscopy and microscopy and PCR are detailed in Table 2.

Discussion

The sensitivity and specificity of the tested RDTs found in this study appear to fall within the ranges quoted in other studies, which reported a sensitivity of Paracheck™-Pf of 82.9–100% and a specificity of 56.0–96.4% [34–42] and a sensitivity of the SD Bioline tests of 83.3–100% and a specificity of 86.8–98.9% [43–45]. WHO standards for RDT procurement for high-transmission areas include a recommendation that the panel detection scores against P. falciparum samples be at least 75% at 200 parasites/μl, although discrepancies between these scores and clinical sensitivity are limitations of these tests [46, 47].

In this study, some blood samples that were negative by microscopic examination gave negative results in all three RDTs, while some gave positive results in all RDTs. Factors that affect the sensitivity and specificity of RDTs, such as low parasitaemia, are particular challenges for malaria diagnosis with these new devices. We found that a parasitaemia between 40 and 400 parasites/μl in blood samples with positive results by microscopy gave negative results in all three RDTs. This finding corroborates those of other studies [48–52], which reported false-negative results with RDTs at a parasitaemia < 500 parasites/μl. It has been suggested that lower levels of HRP2 during a malaria episode with low parasitaemia might not be detected by RDTs [53] because malaria antigenaemia depends on the parasite biomass in the patient’s body during an acute episode [54].

Furthermore, deletions or mutations in the HRP 2 gene may reduce the sensitivity of these RDTs [16–21]. It has also been speculated that the variation in PfHRP2 sequences in samples from the Central African Republic might reduced the sensitivity of RDTs for detecting malaria at very low parasite density [29]. Other factors, such as the ‘prozone effect’ for Paracheck™-Pf at high parasite densities [55] and the presence of anti-HRP 2 in humans [22], might explain why some tests give negative results despite significant parasitaemia.

Cases incorrectly identified as positive by the RDTs might be due to the persistence of PfHRP2 from previous malaria infections [56], cross-reactivity with human autoantibodies [23, 24] or other infectious diseases [25].

This study has some limitations. First, PCR was performed only on samples found negative by microscopy. It might be considered incorrect to use a different “gold standard” for slides found to be positive and those found to be negative by microscopy, by using PCR only for slides found negative by microscopy. However, the risk for false-positive microscopy results was considered low, as the slides were read independently by two experienced technicians. The fact that the microscopists counted only 200 negative leukocytes before declaring a slide as negative might have decreased the sensitivity of microscopic detection in this study. PCR is a useful gold standard because it is highly sensitive, can detect cases with low parasitaemia that are missed by other techniques and is easily reproducible [57]. Nevertheless, it is very expensive and time- and labour-consuming and is therefore used only to confirm the accuracy of microscopy in cases of sub-patent parasitaemia [58] and to evaluate the performance of the RDTs or microscopy in determining malaria prevalence [59].

Conclusions

This study showed that the performance of SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf and SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf/pan was better than that of Paracheck™-Pf. SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf/pan is the most useful test because it detects other species of Plasmodium, even if they are less prevalent in the Central African Republic. Moreover, introduction of these tests will indisputably help to identify malaria cases in this area, where microscopy is still of poor quality. Microscopy should nevertheless complement RDTs for determining parasite density, and therefore reinforcement of microscopy skills by ongoing training of technicians and quality assurance of both RDTs and microscopy should be considered priorities in national malaria programmes. The results of this study also indicate that RDTs should be evaluated in each new setting before they are deployed, in view of possible variations in performance in different populations.

References

Juma E, Zurovac D: Changes in health workers’ malaria diagnosis and treatment practices in Kenya. Malar J. 2011, 10: 1-

Bardaji A, Sigauque B, Bruni L, Romagosa C, Sanz S, Mabunda S, Mandomando I, Aponte J, Sevene E, Alonso PL, Menendez C: Clinical malaria in African pregnant women. Malar J. 2008, 7: 27-

Talisuna AO, Bloland P, D’Alessandro U: History, dynamics, and public health importance of malaria parasite resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004, 17: 235-254.

Myint HY, Tipmanee P, Nosten F, Day NP, Pukrittayakamee S, Looareesuwan S, White NJ: A systematic overview of published antimalarial drug trials. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2004, 98: 73-81.

Watkins WM, Mosobo M: Treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria with pyrimethamine-sulfadoxine: selective pressure for resistance is a function of long elimination half-life. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993, 87: 75-78.

WHO: Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. WHO/HTM/MAL/2006.1108: Accessed on June 20th, 2007; at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2006/9241546948_eng.pdf

White NJ, Olliaro PL: Strategies for the prevention of antimalarial drug resistance: rationale for combination chemotherapy for malaria. Parasitol Today. 1996, 12: 399-401.

WHO: Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. 2010, Geneva: WHO, accessed on February 20th 2013 at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241547925_eng.pdf, 2

WHO: RDT evaluation programme. accessed on February 20th 2013 at http://www.wpro.who.int/malaria/sites/rdt/who_rdt_evaluation/ 2013

Wongsrichanalai C, Barcus MJ, Muth S, Sutamihardja A, Wernsdorfer WH: A review of malaria diagnostic tools: microscopy and rapid diagnostic test (RDT). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007, 77: 119-127.

de Oliveira AM, Skarbinski J, Ouma PO, Kariuki S, Barnwell JW, Otieno K, Onyona P, Causer LM, Laserson KF, Akhwale WS, Slutsker L, Hamel M: Performance of malaria rapid diagnostic tests as part of routine malaria case management in Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009, 80: 470-474.

Murray CK, Gasser RA, Magill AJ, Miller RS: Update on rapid diagnostic testing for malaria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008, 21: 97-110.

Hopkins H, Bebell L, Kambale W, Dokomajilar C, Rosenthal PJ, Dorsey G: Rapid diagnostic tests for malaria at sites of varying transmission intensity in Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2008, 197: 510-518.

Proux S, Hkirijareon L, Ngamngonkiri C, McConnell S, Nosten F: Paracheck-Pf: a new, inexpensive and reliable rapid test for P. falciparum malaria. TM & IH. 2001, 6: 99-101.

Sayang C, Soula G, Tahar R, Basco LK, Gazin P, Moyou-Somo R, Delmont J: Use of a histidine-rich protein 2-based rapid diagnostic test for malaria by health personnel during routine consultation of febrile outpatients in a peripheral health facility in Yaounde, Cameroon. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009, 81: 343-347.

Kumar N, Pande V, Bhatt RM, Shah NK, Mishra N, Srivastava B, Valecha N, Anvikar AR: Genetic deletion of HRP2 and HRP3 in Indian Plasmodium falciparum population and false negative malaria rapid diagnostic test. Acta Trop. 2013, 125: 119-121.

Wurtz N, Fall B, Bui K, Pascual A, Fall M, Camara C, Diatta B, Fall KB, Mbaye PS, Dieme Y, Bercion R, Wade B, Briolant S, Pradines B: Pfhrp2 and pfhrp3 polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Dakar, Senegal: impact on rapid malaria diagnostic tests. Malar J. 2013, 12: 34-

Maltha J, Gamboa D, Bendezu J, Sanchez L, Cnops L, Gillet P, Jacobs J: Rapid diagnostic tests for malaria diagnosis in the Peruvian Amazon: impact of pfhrp2 gene deletions and cross-reactions. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e43094-

Koita OA, Doumbo OK, Ouattara A, Tall LK, Konare A, Diakite M, Diallo M, Sagara I, Masinde GL, Doumbo SN, Dolo A, Tounkara A, Traoré I, Krogstad DJ: False-negative rapid diagnostic tests for malaria and deletion of the histidine-rich repeat region of the hrp2 gene. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012, 86: 194-198.

Houze S, Hubert V, Le Pessec G, Le Bras J, Clain J: Combined deletions of pfhrp2 and pfhrp3 genes result in Plasmodium falciparum malaria false-negative rapid diagnostic test. J Clin Microbiol. 2011, 49: 2694-2696.

Baker J, McCarthy J, Gatton M, Kyle DE, Belizario V, Luchavez J, Bell D, Cheng Q: Genetic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein 2 (PfHRP2) and its effect on the performance of PfHRP2-based rapid diagnostic tests. J Infect Dis. 2005, 192: 870-877.

Biswas S, Tomar D, Rao DN: Investigation of the kinetics of histidine-rich protein 2 and of the antibody responses to this antigen, in a group of malaria patients from India. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2005, 99: 553-562.

Bartoloni A, Sabatinelli G, Benucci M: Performance of two rapid tests for Plasmodium falciparum malaria in patients with rheumatoid factors. N Engl J Med. 1998, 338: 1075-

Iqbal J, Sher A, Rab A: Plasmodium falciparum Histidine-Rich Protein 2-Based Immunocapture Diagnostic Assay for Malaria: Cross-Reactivity with Rheumatoid Factors. J Clin Microbiol. 2000, 38: 1184-1186.

Gillet P, MumbaNgoyi D, Lukuka A, Kande V, Atua B, van Griensven J, Muyembe JJ, Jacobs J, Lejon V: False positivity of non-targeted infections in malaria rapid diagnostic tests: the case of human african trypanosomiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013, 7 (4): e2180-

Chinkhumba J, Skarbinski J, Chilima B, Campbell C, Ewing V, San Joaquin M, Sande J, Ali D, Mathanga D: Comparative field performance and adherence to test results of four malaria rapid diagnostic tests among febrile patients more than five years of age in Blantyre, Malawi. Malar J. 2010, 9: 209-

Kumar N, Singh JP, Pande V, Mishra N, Srivastava B, Kapoor R, Valecha N, Anvikar AR: Genetic variation in histidine rich proteins among Indian Plasmodium falciparum population: possible cause of variable sensitivity of malaria rapid diagnostic tests. Malar J. 2012, 11: 298-

Abba K, Deeks JJ, Olliaro P, Naing CM, Jackson SM, Takwoingi Y, Donegan S, Garner P: Rapid diagnostic tests for diagnosing uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in endemic countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011, 7: CD008122-

Baker J, Ho MF, Pelecanos A, Gatton M, Chen N, Abdullah S, Albertini A, Ariey F, Barnwell J, Bell D, Cunningham J, Djalle D, Echeverry DF, Gamboa D, Hii J, Kyaw MP, Luchavez J, Membi C, Menard D, Murillo C, Nhem S, Ogutu B, Onyor P, Oyibo W, Wang SQ, McCarthy J, Cheng Q: Global sequence variation in the histidine-rich proteins 2 and 3 of Plasmodium falciparum: implications for the performance of malaria rapid diagnostic tests. Malaria journal. 2010, 9: 129-

Manirakiza A, Soula G, Laganier R, Klement E, Djalle D, Methode M, Madji N, Heredeibona LS, Le Faou A, Delmont J: Pattern of the antimalarials prescription during pregnancy in Bangui, Central African Republic. Malaria Research and Treatment. 2011, 2011: 414510-

Laurent A, Schellenberg J, Shirima K, Ketende SC, Alonso PL, Mshinda H, Tanner M, Schellenberg D: Performance of HRP-2 based rapid diagnostic test for malaria and its variation with age in an area of intense malaria transmission in southern Tanzania. Malar J. 2010, 9: 294-

WHO: Basic Laboratory Methods in Medical Parasitology. 1991, Geneva: WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Zhu XP, Jarra W, Pinheiro L, do Rosario VE, Thaithong S, Brown KN: High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993, 61: 315-320.

Guthmann JP, Ruiz A, Priotto G, Kiguli J, Bonte L, Legros D: Validity, reliability and ease of use in the field of five rapid tests for the diagnosis of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Uganda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002, 96: 254-257.

Nigussie D, Legesse M, Animut A, H/Mariam A, Mulu A: Evaluation of Paracheck pf o and Parascreen pan/pf o tests for the diagnosis of malaria in an endemic area, South Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2008, 46: 375-381.

Sharew B, Legesse M, Animut A, Jima D, Medhin G, Erko B: Evaluation of the performance of CareStart malaria Pf/Pv combo and paracheck Pf tests for the diagnosis of malaria in Wondo Genet, Southern Ethiopia. Acta Trop. 2009, 111: 321-324.

Abeku TA, Kristan M, Jones C, Beard J, Mueller DH, Okia M, Rapuoda B, Greenwood B, Cox J: Determinants of the accuracy of rapid diagnostic tests in malaria case management: evidence from low and moderate transmission settings in the East African highlands. Malar J. 2008, 7: 202-

Willcox ML, Sanogo F, Graz B, Forster M, Dakouo F, Sidibe O, Falquet J, Giani S, Diakite C, Diallo D: Rapid diagnostic tests for the home-based management of malaria, in a high-transmission area. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2009, 103: 3-16.

Swarthout TD, Counihan H, Senga RK, van den Broek I: Paracheck-Pf accuracy and recently treated Plasmodium falciparum infections: is there a risk of over-diagnosis?. Malar J. 2007, 6: 58-

Gerstl S, Dunkley S, Mukhtar A, De Smet M, Baker S, Maikere J: Assessment of two malaria rapid diagnostic tests in children under five years of age, with follow-up of false-positive pLDH test results, in a hyperendemic falciparum malaria area, Sierra Leone. Malaria journal. 2010, 9: 28-

Mboera LE, Fanello CI, Malima RC, Talbert A, Fogliati P, Bobbio F, Molteni F: Comparison of the Paracheck-Pf test with microscopy, for the confirmation of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Tanzania. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2006, 100: 115-122.

Kamugisha ML, Msangeni H, Beale E, Malecela EK, Akida J, Ishengoma DR, Lemnge MM: Paracheck Pf® compared with microscopy for diagnosis of Plasmodium falciparum malaria among children in Tanga City, North-Eastern Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2008, 10: 14-19.

Ogouyemi-Hounto A, Kinde-Gazard D, Keke C, Goncalves E, Alapini N, Adjovi F, Adisso L, Bossou C, Denon YV, Massougbodji A: [Assessment of a rapid diagnostic test and portable fluorescent microscopy for malaria diagnosis in Cotonou (Benin)]. Bulletin de la Societe de pathologie exotique. 2013, 106: 27-31.

Kosack CS, Naing WT, Piriou E, Shanks L: Routine parallel diagnosis of malaria using microscopy and the malaria rapid diagnostic test SD 05FK60: the experience of medecins Sans Frontieres in Myanmar. Malar J. 2013, 12: 167-

Kim JY, Ji SY, Goo YK, Na BK, Pyo HJ, Lee HN, Lee J, Kim NH, von Seidlein L, Cheng Q, Cho SH, Lee WJ: Comparison of rapid diagnostic tests for the detection of Plasmodium vivax malaria in South Korea. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e64353-

WHO Global Malaria Programme. Information note on recommended selection criteria for procurement of malaria rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs). Accessed on September 20th, 2013; at http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/rdt_selection_criteria/en/

WHO: Good practices for selecting and procuring rapid diagnostic tests for malaria. Accessed on September 20th, 2013; at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241501125_eng.pdf

Forney JR, Magill AJ, Wongsrichanalai C, Sirichaisinthop J, Bautista CT, Heppner DG, Miller RS, Ockenhouse CF, Gubanov A, Shafer R, DeWitt CC, Quino-Ascurra HA, Kester KE, Kain KC, Walsh DS, Ballou WR, Gasser RA: Malaria rapid diagnostic devices: performance characteristics of the ParaSight F device determined in a multisite field study. J Clin Microbiol. 2001, 39: 2884-2890.

Iqbal J, Khalid N, Hira PR: Comparison of two commercial assays with expert microscopy for confirmation of symptomatically diagnosed malaria. J Clin Microbiol. 2002, 40: 4675-4678.

Pattanasin S, Proux S, Chompasuk D, Luwiradaj K, Jacquier P, Looareesuwan S, Nosten F: Evaluation of a new Plasmodium lactate dehydrogenase assay (OptiMAL-IT) for the detection of malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2003, 97: 672-674.

Ratsimbasoa A, Fanazava L, Radrianjafy R, Ramilijaona J, Rafanomezantsoa H, Menard D: Evaluation of two new immunochromatographic assays for diagnosis of malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008, 79: 670-672.

Shakya G, Gupta R, Pant SD, Poudel P, Upadhaya B, Sapkota A, Kc K, Ojha CR: Comparative study of sensitivity of rapid diagnostic (hexagon) test with calculated malarial parasitic density in peripheral blood. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2012, 10: 16-19.

Desakorn V, Dondorp AM, Silamut K, Pongtavornpinyo W, Sahassananda D, Chotivanich K, Pitisuttithum P, Smithyman AM, Day NP, White NJ: Stage-dependent production and release of histidine-rich protein 2 by Plasmodium falciparum. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005, 99: 517-524.

Dondorp AM, Desakorn V, Pongtavornpinyo W, Sahassananda D, Silamut K, Chotivanich K, Newton PN, Pitisuttithum P, Smithyman AM, White NJ, Day NP: Estimation of the total parasite biomass in acute falciparum malaria from plasma PfHRP2. PLoS Med. 2005, 2: e204-

Gillet P, Mori M, Van Esbroeck M, Van den Ende J, Jacobs J: Assessment of the prozone effect in malaria rapid diagnostic tests. Malar J. 2009, 8: 271-

Mayxay M, Pukrittayakamee S, Chotivanich K, Looareesuwan S, White NJ: Persistence of Plasmodium falciparum HRP-2 in successfully treated acute falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001, 95: 179-182.

Johnston SP, Pieniazek NJ, Xayavong MV, Slemenda SB, Wilkins PP, DaSilva AJ: PCR as a confirmatory technique for laboratory diagnosis of malaria. J Clin Microbiol. 2006, 44: 1087-1089.

Coleman RE, Sattabongkot J, Promstaporm S, Maneechai N, Tippayachai B, Kengluecha A, Rachapaew N, Zollner G, Miller RS, Vaughan JA, Thimasarn K, Khuntirat B: Comparison of PCR and microscopy for the detection of asymptomatic malaria in a Plasmodium falciparum/vivax endemic area in Thailand. Malar J. 2006, 5: 121-

Fançony C, Sebastião YV, Pires JE, Gamboa D, Nery SV: Performance of microscopy and RDTs in the context of a malaria prevalence survey in Angola: a comparison using PCR as the gold standard. Malar J. 2013, 12: 284-

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/14/109/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Mirdad Kazanji, Director of the Pasteur Institut of Bangui, and Professor Elisabeth Heseltine for critically reading the manuscript and for comments and suggestions. This study was funded by the Standard Diagnostics Ref 05FK60 Laboratory Inc., Suwon City, Republic of Korea and the Central African Republic Malaria Programme Division. The authors are grateful to all the patients who participated in this study. They also thank the technicians who performed the laboratory analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

DD and JMM conceived the study, with substantial contributions from AM and NM. DD, JI, JCG and GT participated in field data collection and laboratory analysis. AM, DD and SB interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final version.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Djallé, D., Gody, J.C., Moyen, J.M. et al. Performance of Paracheck™-Pf, SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf and SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf/pan for diagnosis of falciparum malaria in the Central African Republic. BMC Infect Dis 14, 109 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-109

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-109