Abstract

Background

Realization of the public health benefits of mass drug administration (MDA) for the control of schistosomiasis depends on achieving and maintaining high annual treatment coverage. In Uganda, the uptake of preventive treatment for schistosomiasis among school-age children in 2011 was only 28%. Strategies are needed to increase uptake.

Methods

Serial cross-sectional surveys were conducted at baseline (after MDA in 2011) and at follow-up MDA in 2012 where teacher motivation was provided and supervision strengthened in Jinja district of Uganda. Uptake of praziquantel was assessed in 1,010 randomly selected children from 12 primary schools during the baseline survey and in another set of 1,020 randomly selected children from the same primary schools during the follow-up survey.

Results

Self-reported uptake of praziquantel increased from 28.2% (95% CI 25.4%-30.9%) at baseline to 48.9% (95% CI 45.8%-52.0%) (p < 0.001) at follow-up. Prevalence and intensity of Schistosoma mansoni infection were unchanged and moderate on both occasions; 35.0% (95% CI: 25.4%-37.9%) and 32.6% (95% CI: 29.6%-35.5%) (p = 0.25) and 156.7 eggs per gram of stool (epg) (95% CI: 116.9-196.5) and 133.1 epg (95% CI: 99.0-167.2) (p = 0.38), respectively. There was no change in the proportion of children reporting side effects attributable to praziquantel at baseline (49.8%, 95% CI 43.8%-55.8%) and at follow-up (46.6%, 95% CI 42%.1-51.2%) (p = 0.50) as well as in the proportion of children with correct knowledge of schistosomiasis transmission and control between the baseline (45.9%, 95% CI 42.7%-73.7%) and follow-up (44.1%, 95% CI 41.0%- 47.2%) (p = 0.42).

Conclusion

Although teacher motivation and supervision to distribute treatment increased the uptake of praziquantel among school-age children, the realized uptake is still lower than is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) and apparently too low to affect the prevalence and intensity of schistosomiasis among the children. Additional measures are needed to increase uptake of praziquantel if school-based MDA is to achieve the objective of preventive chemotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends treatment programs for schistosomiasis to target school-age children who could be reached through the primary school system, in collaboration with the education sector [1]. This method is considered affordable and cost-effective [2, 3]. The goal is to provide regular treatment to at least 75% of school-age children at risk of morbidity [4, 5]. Successful schistosomiasis control programs have been implemented in many countries [4–9]. Varying levels of success have been reported in many developing countries where regular chemotherapy with praziquantel is implemented as the main strategy for schistosomiasis control [9–13].

In Uganda, the national program for the control of schistosomiasis adopted the WHO recommendations in 2003 and has since implemented school-based MDA with praziquantel in high burden communities [14]. Realization of the public health benefits of MDA, such as reduction in prevalence, intensity of infection and morbidity attributable to schistosomiasis, will depend on achieving and maintaining high annual treatment coverage. However, previous studies in Uganda have reported a very low uptake of praziquantel in some areas [11, 15, 16]. A baseline of the present study conducted in primary schools of Jinja district showed that less than 30% of school children took praziquantel during the 2011 MDA [11]. Thus, measures are needed to increase uptake of MDA in Uganda. Following the very low uptake in 2011, the Ugandan national program attempted to remedy the situation by adopting new strategies for distribution of praziquantel. This paper reports the effects of the new strategy implemented in 2012 on levels of uptake, children’s knowledge on schistosomiasis prevention and prevalence and intensity of schistosomiasis before and after implementation.

Methods

Study design

Serial cross-sectional surveys were carried out in 2011 and 2012 in Jinja district. A survey before the 2011 MDA (hereafter referred to as the baseline) was conducted in September 2011, six months after the 2010 MDA. Another survey was conducted in July 2012, three weeks after the 2012 MDA (hereafter referred to as the follow-up survey). Both surveys employed similar methods of data collection.

Study setting

The surveys were carried out in the 12 primary schools of Walukuba division, Jinja district of south-eastern Uganda, where schistosomiasis is highly endemic. This setting has been described elsewhere [11].

Implementation of MDA in the primary schools during the 2011 MDA

During the 2011 MDA, praziquantel was distributed to children on a grade basis, whereby, each grade (year of study) was invited at a time, to receive treatment that was distributed from one pre-arranged central place in each school. The teachers distributed the drug to the children using a standard dose pole and recorded the treatment in the registers. The fear of treatment, lack of teacher support to distribute treatment, and lack of knowledge about schistosomiasis transmission and prevention were some of the major reasons for the low uptake of praziquantel during the 2011 MDA [11]. Lack of funds to conduct trainings, cover teachers’ allowances and to facilitate support supervision were deemed responsible for this state of affairs.

Strategies to improve uptake of praziquantel in 2012 MDA

Prior to the MDA in 2012, all teachers responsible for distributing and recording treatment in the respective schools received a one days’ refresher training in drug distribution and recording and a small allowance of 2 US $ per teacher. In addition, all the school teachers received T-shirts with inscriptions “NTD control program” on the front and “Get rid of neglected diseases for better health” at the back. Based on the assumption that there are about 12 teachers in each primary school, a total of 12 T-shirts were distributed to each school. In addition, all members of the district health team and the health inspectorate staff also received T-shirts. Furthermore, supervision of MDA by the district health staff was strengthened through provision of transport allowances to facilitate the staff to visit the schools and provide technical support to the teachers during drug distribution. This facilitation was provided by the vector control division, Ministry of Health with support from USAID. It was anticipated that the re-training, strengthened supervision and provision of such incentives to the teachers would uplift their enthusiasm to distribute the drugs to the children and increase uptake.

Sample size

The uptake of praziquantel used to estimate the sample size for this study was derived from the baseline study [11]. It was assumed that after increasing teacher motivation and strengthening supervision, the uptake would increase by 10%. At 90% power and 95% confidence interval (CI), the sample size required to detect this increase for cross sectional studies is 483 in the follow-up survey according to STATA 10.0 (TX, USA). This sample size was adjusted by 5% non-response to 507. A design effect of 2 was applied to obtain a minimum sample size of 1,014. In this study, 1,020 children were randomly selected from the 12 primary schools to participate in the follow-up survey.

Sampling and data collection

The study employed similar sampling and data collection methods as those used in the baseline study. The children were randomly selected from grade (year) 4–6 in the 12 primary schools. The number of children to participate in the study from each school and grade was determined by probability proportional to size of the school and grade population. The grade registers, where the names of the children are arranged in alphabetical order, were used as the sampling frame. Systematic sampling was used to select the number of children from each grade to participate in the face to face interviews using a structured questionnaire and undergo a stool examination for S. mansoni infection.

Measures

Children were questioned about their socio-demographic characteristics, whether they took praziquantel at the last MDA and whether they experienced any problems after swallowing the drug. Uptake of praziquantel was measured through self-report and was defined as having received and swallowed praziquantel tablets at the last MDA. In addition, knowledge of schistosomiasis transmission and prevention was measured on a score scale of 1–3. The children were asked to mention the different ways through which the infection can be acquired and prevented, including taking preventive treatment. Various correct options of the disease transmission and prevention methods were listed on the questionnaire and for each of the correct responses, a score of 1 was awarded. Children who mentioned at least one correct method of transmission and two correct methods of prevention scored an aggregate of 3 and were regarded as having correct knowledge of schistosomiasis transmission and control. The prevalence and intensity of S. mansoni infection was determined by examining one stool sample on two consecutive days from each child using the Kato-Katz faecal thick smear technique [17].

Statistical analysis

Analysis was done at the school level to obtain school-specific uptake of praziquantel, prevalence and intensity of S. mansoni infection. Mean and standard deviation (S.D) were used to describe continuous data. Within-school clustering was adjusted for using the cluster robust option and robust standard errors were used. 95% CI was used for all the analyses. Chi-square test was used to compare uptake levels, prevalence of infection, knowledge of schistosomiasis transmission and prevention and occurrence of side effects between the baseline and follow-up surveys. Kruskal Wallis test was used to compare intensity of infection between the two surveys. STATA 10.0 (TX, USA) was used for analysis.

Quality control

We pre-visited the study primary schools to obtain updated sampling frames. Experienced research assistants conducted the interviews. These were trained in data collection methods. Data was checked for completeness and accuracy before leaving the school premises. The principal investigator closely supervised the research assistants during data collection.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from Makerere University College of Health Sciences Higher Degrees, Research and Ethics Committee and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology. Permission to conduct the study in the schools was obtained from the school management. Informed consent was obtained from parents of the children selected to participate in the study. Assent was obtained from the children. Children identified with S. mansoni and/or soil-transmitted helminth (STH) infections were treated with praziquantel and/or albendazole. Confidentiality was maintained by using a coding system.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Overall, a total of 2,030 children were interviewed and their stool examined for S. mansoni infection: 1,010 during the baseline survey and another 1,020 during the follow-up survey. The mean age was 11.6 years (S.D 1.8) and 11.5 years (S.D 1.7) (p = 0.92) at the baseline and follow-up surveys, respectively. The proportion of females was 55.0% and 53.2% during the baseline and follow-up surveys, respectively (p = 0.55). Table 1 shows that the baseline and follow-up samples were comparable in terms of sex, age, and prevalence and intensity of infection with schistosomiasis.

Self-reported uptake of praziquantel

A significant increase was observed in the proportion of children who reported to have taken praziquantel from 28.2% (95% CI 25.4%-30.9%) at baseline to 48.9% (95% CI 45.8%-52.0%) at the follow-up survey (p < 0.001). Uptake at baseline and follow-up survey ranged from 11.2% to 69.0% and from 13.3% to 60.9%, respectively (Table 2). Uptake among schools that reported moderate uptake at baseline (≥ 50%) did not increase. In schools 4 and 5, uptake decreased from 69.0% to 39.4% and from 64.5% to 41.4%, respectively. In school 9, uptake did not change. In the rest of the schools with an uptake of less than 50% at baseline, uptake increased in 7 (77.8%) of the schools at follow-up.

Prevalence and intensity of S. mansoniinfection

Prevalence and intensity of S. mansoni infection was unchanged between the baseline and follow-up surveys with 35.0% (95% CI: 25.4%-37.9%) and 32.6% (95% CI: 29.6%-35.5%) (p = 0.25) and 156.7 epg (95% CI: 116.9-196.5) and 133.1 epg (95% CI: 99.0-167.2) (p = 0.38), respectively. Substantial variations in prevalence (and intensity) of S. mansoni infection across the 12 schools were observed at baseline and follow-up surveys and ranged from 16.3% (10.1 epg) to 96.8% (1,419.1 epg) and from 20.7% (18.3 epg) to 78.9% (778.5 epg), respectively (Tables 3 and 4). Significant decrease in prevalence of infection was observed in schools 4, 5 and 6 between the two surveys. Intensity of infection significantly reduced in school 5 but increased in schools 11 and 12 between the two surveys (Table 4).

Occurrence of side effects and knowledge of schistosomiasis transmission and control

Comparison of other parameters at baseline and follow-up included the occurrence of side effects attributable to praziquantel and knowledge of schistosomiasis transmission and prevention. There was no change in the proportion of children who reported to have experienced side effects after swallowing the drugs at follow-up (46.6%, 95% CI: 42.1%-51.2%) from the baseline (49.8%, 95% CI: 43.8%-55.8%) (p = 0.55). Similarly, there was no change in the proportion of children who had correct knowledge of schistosomiasis transmission and control at follow-up (44.1%, 95% CI: 41.0%-47.2%) from the baseline (45.9%, 95% CI: 42.7%-48.9%) (p = 0.42).

Discussion

The self-reported uptake of praziquantel among school-age children increased from 28.2% to 48.9% between the two surveys. There was no change in prevalence and intensity of S. mansoni infection as well as in levels of knowledge on schistosomiasis transmission and control and occurrence of side effects attributable to uptake of praziquantel.

Although the increase in uptake of praziquantel was statistically significant, it is unlikely to have public health impact as observed by the persistent high prevalence and intensity of infection with schistosomiasis in the schools. The observed increase in self-reported uptake may be attributable to the high level of engagement between the district health team and the teachers during MDA as well as the provision of incentives including facilitation allowances and T-shirts to the school teachers prior to MDA. Such incentives have been found useful in motivating drug distributors [18]. In addition, improvement in self-reported uptake could have been as a result of a more intensive follow-up by the district health team and the presence of researchers in the schools during the pre-visits and drug distribution. Such measured improvements in an aspect of behaviour due to the subjects’ awareness that they are being studied, the so-called “Hawthorne effect”, have been reported in other studies [19, 20]. It is worrying that schools with moderate uptake at baseline did not improve and even declined at follow-up. A possible explanation is that concerted efforts to improve uptake, such as the supervision of teachers by the district health team during MDA, were concentrated on schools with very low uptake at baseline. This observation suggests that modification of the conventional school-based MDA programs may possibly improve drug uptake and further studies are needed to test this hypothesis.

The efficacy of praziquantel against S. mansoni infection is indisputable [3, 8, 21–23]. With improved uptake, one would expect a reduction in prevalence and intensity of the infection. Indeed, significant reductions in prevalence were observed in schools (4, 5 and 6) with high uptake levels. It is important to note that this is not a cohort study which follows the same children from baseline to follow-up. In the present study, the two study populations in the two different time-points are not completely identical. The persistent high infections despite the increased uptake of praziquantel could be attributable to the fact that the realized level of uptake is lower than is recommended by the WHO and apparently too low to affect the prevalence and intensity of schistosomiasis among the children. Another factor that could have contributed to the sustained high prevalence and intensities of infection despite the increase in uptake level is that praziquantel is not effective against juvenile schistosomes [24]. The observed eggs may have been a result of immature schistosomes developing into egg laying adult worms during the follow-up period. In this study, 67% of the schools are located within a 5 km radius from lake victoria. Children from schools located closer to the lake frequently visit the lake to fetch water, bathe, to wash, and to swim [25] and therefore get infected with schistosomiasis when they get into contact with contaminated water. This explains the variations in prevalence and geometric mean intensity across the different schools.

The fear of side effects of praziquantel, lack of knowledge about schistosomiasis transmission and prevention and lack of teacher support to take preventive treatment were highlighted as some of the major factors associated with the low uptake among school-age children as reported in the ealier paper from this study [11]. In the follow-up of this study, approximately 50% of the children who received treatment reported to have developed side effects and as such, resistance to swallow the treatment is perhaps inevitable as majority indicated that they would not swallow the drug during the subsequent MDA. Praziquantel causes transient side-effects of the gastro-intestinal and central nervous system including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache and dizziness, especially when the drug is taken on an empty stomach [23, 26, 27]. To mitigate the side-effects, the drug should be taken with food [26]. However, most children in rural areas do not take any meals while at school [28] and some take treatment on empty stomachs and experience the side-effects [2, 22, 29]. Considerable reduction in occurrence of side-effects has been reported in countries where praziquantel was administered with food [2, 10]. Therefore, implementing measures for mitigating the side effects attributable to praziquantel, such as providing food during MDA, may improve uptake of the drug among school children. High coverage of praziquantel treatment among school children was achieved by the national control program in Sierra Leone, where a special feeding program for the children to mitigate the side effects was provided [10].

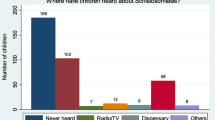

Knowledge of schistosomiasis transmission and control was evidently lacking in more than 50% of the children interviewed, a manifestation of the insufficient health education provided prior to and during MDA. During MDA, distribution of praziquantel takes precedence with diminutive, if any, health education on the infection transmission and control. In the absence of this knowledge and with lack of a clear understanding of the rationale of preventive treatment, there is a risk that the targeted populations may resist the treatment [16, 30]. Improved compliance to treatment for schistosomiasis has been reported among school children with adequate knowledge of schistosomiasis transmission and prevention [11, 30–32]. In this study, there was a considerable variation in levels of knowledge of schistosomiasis transmission and prevention across the primary schools that ranged from 12.8% to 73.2% at baseline and from 27% to 69% at follow-up. This variation in levels of knowledge of schistosomiasis transmission and prevention could explain the differences in uptake levels of treatment, and prevalence and intensity of infection across the primary schools in the two different time-points. Health education programs for providing school children with information about transmission and prevention are required if sustained drop in prevalence and intensity of S. mansoni infection among school children is to be achieved. It is urged that with chemotherapy, prevalence and intensity of decrease when health education is concurrently implemented [30, 33].

Study limitations

The lack of a comparison group makes it difficult to attribute the observed increase in uptake to strengthened supervision and teacher motivation strategy. Moreover, because data on self-reported uptake were derived from interviews, it is possible that the children could have provided desirable answers. However, the comparison of our findings with those of previous studies in other settings lend credibility to our observations and suggest that the observed increase in uptake could have ensued from the strengthened supervision by the district health team and teacher motivation to distribute the drugs [32, 33]. The second limitation is the relatively low intrinsic capacity of the Kato-Katz technique to recover parasite eggs from specimens of low infection intensities compared to other parasitological methods [34, 35]. To increase its sensitivity during the study, two samples were taken from each child and two slides were prepared per fecal sample.

Conclusions

Strengthening supervision and increasing teacher motivation to distribute treatment is an important but not sufficient strategy for improving uptake of praziquantel. Uptake must be further increased to significantly reduce levels of transmission of infection. The strategies for improving uptake could be health education and/or measures to mitigate the side effects of the drug, such as provision of a snack during MDA. Randomized controlled trial studies should be undertaken to evaluate such interventions.

References

Engels D, Chitsulo L, Montresor A, Savioli L: The global epidemiological situation of schistosomiasis and new approaches to control and research. Acta Trop. 2002, 82 (2): 139-146. 10.1016/S0001-706X(02)00045-1.

Brooker S, Marriot H, Hall A, Adjei S, Allan E, Maier C, Bundy DA, Drake LJ, Coombes MD, Azene G, et al: Community perception of school-based delivery of anthelmintics in Ghana and Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 2001, 6 (12): 1075-1083. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00806.x.

Magnussen P, Ndawi B, Sheshe AK, Byskov J, Mbwana K, Christensen NO: The impact of a school health programme on the prevalence and morbidity of urinary schistosomiasis in Mwera Division, Pangani District, Tanzania. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001, 95 (1): 58-64. 10.1016/S0035-9203(01)90333-5.

Savioli L, Gabrielli AF, Montresor A, Chitsulo L, Engels D: Schistosomiasis control in Africa: 8 years after World Health Assembly Resolution 54.19. Parasitology. 2009, 136 (13): 1677-1681. 10.1017/S0031182009991181.

WHO: Prevention and control of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis: report of a WHO expert committee. WHO Tech Rep Ser. 2002, Geneva: WHO

Chitsulo L, Engels D, Montresor A, Savioli L: The global status of schistosomiasis and its control. Acta Trop. 2000, 77 (1): 41-51. 10.1016/S0001-706X(00)00122-4.

El Khoby T, Galal N, Fenwick A: The USAID/Government of Egypt’s Schistosomiasis Research Project (SRP). Parasitol Today. 1998, 14 (3): 92-96. 10.1016/S0169-4758(97)01206-4.

Kabatereine NB, Brooker S, Koukounari A, Kazibwe F, Tukahebwa EM, Fleming FM, Zhang Y, Webster JP, Stothard JR, Fenwick A: Impact of a national helminth control programme on infection and morbidity in Ugandan schoolchildren. Bull World Health Organ. 2007, 85 (2): 91-99. 10.2471/BLT.06.030353.

Montresor A, Cong DT, Sinuon M, Tsuyuoka R, Chanthavisouk C, Strandgaard H, Velayudhan R, Capuano CM, Le Anh T, Tee Dato AS: Large-scale preventive chemotherapy for the control of helminth infection in Western Pacific countries: six years later. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008, 2 (8): e278-10.1371/journal.pntd.0000278.

Hodges MH, Dada N, Warmsley A, Paye J, Bangura MM, Nyorkor E, Sonnie M, Zhang Y: Mass drug administration significantly reduces infection of Schistosoma mansoni and hookworm in school children in the national control program in Sierra Leone. BMC Infect Dis. 2012, 12: 16-10.1186/1471-2334-12-16.

Muhumuza S, Olsen A, Katahoire A, Nuwaha F: Uptake of preventive treatment for intestinal schistosomiasis among school children in Jinja district, Uganda: a cross sectional study. PLoS One. 2013, 8 (5): e63438-10.1371/journal.pone.0063438.

Mwinzi PN, Montgomery SP, Owaga CO, Mwanje M, Muok EM, Ayisi JG, Laserson KF, Muchiri EM, Secor WE, Karanja DM: Integrated community-directed intervention for schistosomiasis and soil transmitted helminths in western Kenya - a pilot study. Parasit Vectors. 2012, 5: 182-10.1186/1756-3305-5-182.

Zhang Y, Koukounari A, Kabatereine N, Fleming F, Kazibwe F, Tukahebwa E, Stothard JR, Webster JP, Fenwick A: Parasitological impact of 2-year preventive chemotherapy on schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in Uganda. BMC Med. 2007, 5: 27-10.1186/1741-7015-5-27.

Kabatereine NB, Brooker S, Tukahebwa EM, Kazibwe F, Onapa AW: Epidemiology and geography of Schistosomiaisis mansoni in Uganda: implications for planning control. Trop Med Int Health. 2004, 9: 372-380. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01176.x.

Parker M, Allen T: Does mass drug administration for the integrated treatment of neglected tropical diseases really work? Assessing evidence for the control of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths in Uganda. Health Res Policy Syst. 2011, 9: 3-10.1186/1478-4505-9-3.

Parker M, Allen T, Hastings J: Resisting control of neglected tropical diseases: dilemmas in the mass treatment of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths in north-west Uganda. J Biosoc Sci. 2008, 40 (2): 161-181.

Katz N, Chaves A, Pellegrino J: A simple device for quantitative stool thick-smear technique in Schistosomiasis mansoni. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1972, 14 (6): 397-400.

Nuwaha F, Okware J, Ndyomugyenyi R: Predictors of compliance with community-directed ivermectin treatment in Uganda: quantitative results. Trop Med Int Health. 2005, 10 (7): 659-667. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01436.x.

Fox NS, Brennan JS, Chasen ST: Clinical estimation of fetal weight and the Hawthorne effect. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008, 141 (2): 111-114. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.07.023.

McCarney R, Warner J, Iliffe S, van Haselen R, Griffin M, Fisher P: The Hawthorne Effect: a randomised, controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007, 7: 30-10.1186/1471-2288-7-30.

De Clercq D, Vercruysse J, Kongs A, Verle P, Dompnier JP, Faye PC: Efficacy of artesunate and praziquantel in Schistosoma haematobium infected schoolchildren. Acta Trop. 2002, 82 (1): 61-66. 10.1016/S0001-706X(02)00003-7.

Kabatereine NB, Kemijumbi J, Ouma JH, Sturrock RF, Butterworth AE, Madsen H, Ornbjerg N, Dunne DW, Vennnervald BJ: Efficacy and side effects of praziquantel treatment in a highly endemic Schistosoma mansoni focus at Lake Albert, Uganda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2003, 97 (5): 599-603. 10.1016/S0035-9203(03)80044-5.

N’Goran EK, Gnaka HN, Tanner M, Utzinger J: Efficacy and side-effects of two praziquantel treatments against Schistosoma haematobium infection, among schoolchildren from Cote d’Ivoire. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2003, 97 (1): 37-51. 10.1179/000349803125002553.

Davis A: Recent advances in schistosomiasis. Q J Med. 1986, 58 (226): 95-110.

Muhumuza S, Kitimbo G, Oryema-Lalobo M, Nuwaha F: Association between socio economic status and schistosomiasis infection in Jinja District, Uganda. Trop Med Int Health. 2009, 14 (6): 612-619. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02273.x.

Mandour ME, el Turabi H, Homeida MM, el Sadig T, Ali HM, Bennett JL, Leahey WJ, Harron DW: Pharmacokinetics of praziquantel in healthy volunteers and patients with schistosomiasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990, 84 (3): 389-393. 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90333-A.

Stelma FF, Talla I, Sow S, Kongs A, Niang M, Polman K, Deelder AM, Gryseels B: Efficacy and side effects of praziquantel in an epidemic focus of Schistosoma mansoni. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995, 53 (2): 167-170.

GCNF: School Feeding in Uganda, 2006. Report for the Global Child Nutrition Forum. 2006, http://www.gcnf.org/library/country-reports/uganda/2006-Uganda-School-Feeding.pdf [cited 25 August 2011]

Ndyomugyenyi R, Kabatereine N: Integrated community-directed treatment for the control of onchocerciasis, schistosomiasis and intestinal helminths infections in Uganda: advantages and disadvantages. Trop Med Int Health. 2003, 8 (11): 997-1004. 10.1046/j.1360-2276.2003.01124.x.

Lansdown R, Ledward A, Hall A, Issae W, Yona E, Matulu J, Mweta M, Kihamia C, Nyandindi U, Bundy D: Schistosomiasis, helminth infection and health education in Tanzania: achieving behaviour change in primary schools. Health Educ Res. 2002, 17 (4): 425-433. 10.1093/her/17.4.425.

Asaolu SO, Ofoezie IE: The role of health education and sanitation in the control of helminth infections. Acta Trop. 2003, 86 (2–3): 283-294.

Yuan LP, Manderson L, Ren MY, Li GP, Yu DB, Fang JC: School-based interventions to enhance knowledge and improve case management of schistosomiasis: a case study from Hunan, China. Acta tropica. 2005, 96 (2): 248-254.

Schall V, Diniz MCP: Information and education in schistosomiasis control: an analysis of the situation in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2001, 96: 35-43.

Glinz D, Silue KD, Knopp S, Lohourignon LK, Yao KP, Steinmann P, Rinaldi L, Cringoli G, N’Goran EK, Utzinger J: Comparing diagnostic accuracy of Kato-Katz, Koga agar plate, ether-concentration, and FLOTAC for Schistosoma mansoni and soil-transmitted helminths. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010, 4 (7): e754-10.1371/journal.pntd.0000754.

Montresor A: Cure rate is not a valid indicator for assessing drug efficacy and impact of preventive chemotherapy interventions against schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011, 105 (7): 361-363. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.04.003.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/13/590/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank the research assistants Akankwasa Angel, Nabweteme Angella, Ampurire Joy, Bafumba Grace, Osire Peter, Kagwalo Geofrey, Nakaye Alice, Kembabazi Diane, Alaboro Mary, Ssekiwano Samson, Funga Moses, Tiriyeitu Samuel, Sserwadda Ivan, Isabirye Hamuza and Bayenda Gilbert who participated in data collection. We acknowledge the cooperation of the staff of Ministry of Health, Vector Control Division, Uganda, especially Dr Tukahebwa Edrida, Turinawe Wilber and Nsimire Ephrance for their support in the laboratory work of the study. We are grateful to DANIDA for funding the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SM, AK, FN and AO participated in the design of the study. SM participated in data collection. SM and FN performed the statistical analysis. SM drafted the article. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Muhumuza, S., Katahoire, A., Nuwaha, F. et al. Increasing teacher motivation and supervision is an important but not sufficient strategy for improving praziquantel uptake in Schistosoma mansonicontrol programs: serial cross sectional surveys in Uganda. BMC Infect Dis 13, 590 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-590

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-590