Abstract

Background

Fluoroquinolones are used with increasing frequency in children with a major risk of increasing the emergence of FQ resistance. FQ use has expanded off-label for primary antibacterial prophylaxis or treatment of infections in immune-compromised children and life-threatening multi-resistant bacteria infections. Here we assessed the prescriptions of ciprofloxacin in a pediatric cohort and their appropriateness.

Methods

A monocenter audit of ciprofloxacin prescription was conducted for six months in a University hospital in Paris. Infected site, bacteriological findings and indication, were evaluated in children receiving ciprofloxacin in hospital independently by 3 infectious diseases consultants and 1 hospital pharmacist.

Results

Ninety-eight ciprofloxacin prescriptions in children, among which 52 (53.1%) were oral and 46 (46.9%) parenteral, were collected. 45 children had an underlying condition, cystic fibrosis (CF) (21) or an innate or acquired immune deficiency (24). Among CF patients, the most frequent indication was a broncho-pulmonary Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection (20). In non-CF patient, the major indications were broncho-pulmonary (25), urinary (8), intra-abdominal (7), operative site infection (5) and bloodstream/catheter (2/4) infection. 62.2% were microbiologically documented. Twenty-three (23.4%) were considered “mandatory”, 48 (49.0%) “alternative” and 27 (27.6%) “unjustified”.

Conclusion

In our university hospital, only 23.4% of fluoroquinolones prescriptions were mandatory in children, especially in Pseudomonas aeruginosa healthcare associated infection. Looking to the ecological risk of fluoroquinolones and the increase consumption in children population we think that a control program should be developed to control FQ use in children. It could be done with the help of an antimicrobial stewardship team.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Fluoroquinolones (FQ) are licensed and widely indicated for use in adults, owing to the agents’ broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, their extensive tissue and intracellular penetration, and their suitability for oral administration. However, FQ use in pediatric patients has been contraindicated by regulatory authorities in the United States and the European Union, given the cartilage damage that they may induce in juvenile animal models. Nonetheless, FQ use in pediatric patients has increased as shown in the United States, where approximately 520,000 prescriptions were written for children and adolescents younger than 18 years in 2002 [1]. The safety of fluoroquinolones is questioned in pediatric population [2]. Joint disorder and arthromyalgia could be as frequent as 8.3% [3–5]. In pediatric cystic fibrosis patients with acute pulmonary exacerbation caused by P. aeruginosa[6], ciprofloxacin is initially administered intravenously at a dose of 30 mg/kg/day divided every 8 h, followed by an oral administration at 40 mg/kg/day divided every 12 h [7]. Simultaneously, FQ use has expanded off-label for primary antibacterial prophylaxis or treatment of infections in immune-compromised patients, infections due to life-threatening multi-resistant bacteria, or salmonellosis or shigellosis and cholangitis [1, 6, 8, 9]. In 2004, ciprofloxacin became the first fluoroquinolone agent approved by United States Food and Drug Administration for use in children 1 through 17 years of age [10]. As suggested by several studies [11–13] the increased use of fluoroquinolones will subsequently contribute to the spread of resistance.

The aim of this observational study was to evaluate the prescription of ciprofloxacin for pediatric infections.

Methods

A mono-center audit of ciprofloxacin prescription was conducted between 1st December 2007 and 31st May 2008 at Necker-Enfants malades University hospital in Paris. All consecutive pediatric patients (age <18 years) admitted in our hospital, with fluoroquinolone prescribed in hospital were included in this study. All prescriptions were identified by pharmacy’s computer. Descriptive data concerning patients’ characteristics (age, underlying disease, current status, immune status such as neutropenia <500/mm3 or immunosuppressive agent use such as receiving 1 mg/kg/d prednisone for more than 1 weeks or equivalent), the current ciprofloxacin regimen (drug, indication and bacteriologic findings, justification for use, concomitant drugs administered) were collected from patients’ medical documents.

Nosocomial infection was defined as an episode of infection from patients who had been hospitalized for 48 hours or longer while health care-associated infection was defined as from a patient at the time of hospital admission or within 48 hours of admission if the patient fulfilled any of the following criteria (hemodialysis, intravenous chemotherapy during the past 30 days, hospitalization for at least two days during the past 90 days, home intravenous therapy or wound care during the past 30 days). Community-acquired infection was defined as an episode of infection at the time of hospital admission or within the 48 hours after hospital admission for patients who did not fit the criteria for a health care-associated infection [14].

The short-term side effects, such as nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, headache, rash or photosensitivity, arthralgia and myalgia, were reported by patient’s physician during the whole hospitalization and reviewed twice weekly by our mobile infectious diseases team (1 resident, 2 senior physicians and 1 professor in infectious diseases).

Appropriateness of ciprofloxacin prescription was retrospective performed separately by three experts in infectious diseases and one hospital pharmacist. Prescriptions were categorized as “mandatory, alternative or unjustified”. Ciprofloxacin use was considered “mandatory” if susceptibility testing showed resistance to all beta-lactams and TMP-SMX; susceptible only to FQ, or aminoglycoside or colistin, or the ciprofloxacin was the only oral therapy available.

Prescriptions were considered “alternative” in the setting of ciprofloxacin use being indicated by clinical situation or susceptibility testing, in the presence of an available alternative enteral or parenteral antibiotic choice. Finally “unjustified” prescriptions were defined as ciprofloxacin prescription not indicated according to the clinical situation, and/or susceptibility results. The latter two groups defined the inappropriate fluoroquinolone usage.

For the discharged children, the follow-up and monitoring was performed by their respective physician and adverse events were reported to our mobile team if myalgia or arthralgia was mentioned by patients.

Data protection was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital. No ethical committee approval was required under French regulations.

Results

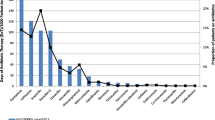

A total of 11,268 children were admitted between 1st December 2007 and 31st May 2008 at the Necker-Enfants malades hospital in Paris. 98 new ciprofloxacin prescriptions were collected. Prescriptions mainly originated from general pediatric wards (22.4%), immuno-hematology department (20.4%), polyvalent intensive care units (12.2%), cardiac surgery unit (11.2%), general surgery (9.2%) and orthopedic surgery (9.2%). Twenty-one patients with cystic fibrosis and 77 without CF received at least one dose of ciprofloxacin during the study period.

Demographic characteristics and underlying diseases of the population

The median age of the 98 children receiving ciprofloxacin was 10 years (1 month – 15 years). 35 were younger than 2 years, 17 were ≥2 and <6 years old, and 46 were ≥6 years up to puberty onset. The gender ratio was 1.3 (M/F). 45/98 (45.9%) had an underlying condition, the most frequent being cystic fibrosis (n = 21, 21.4%), followed by immune deficiencies such as neutropenia (<500/mm3) or severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) (12.2%) or use of any immunosuppressive agent (12.2%) (corticosteroids, cyclosporine or tacrolimus) because of solid organ transplant (3 hepatic, 2 intestinal and hepatic, 1 intestinal, 1 renal and 1 cardiac) and 4 others (glycogenosis, hemophagocytosis syndrome, osteopetrosis and Wegener’s granulomatosis).

Type of infections

Sixty-two infections were nosocomially-acquired, twenty-four were healthcare-associated and thirty-five were community acquired. The remaining child received ciprofloxacin for prophylaxis during orthopedic surgery (Table 1).

Table 2 reports the site of infections and the bacteriological findings. In CF patients, the most frequent clinical indications were P. aeruginosa (95.2%) or methicillin-resistant S. aureus broncho-pulmonary infection (4.8%). In non-CF patients, P. aeruginosa infections represented 16.9% of the ciprofloxacin prescriptions.

Adequacy of ciprofloxacin prescriptions

The median ciprofloxacin’s dosage (Table 3) was 40 mg/kg/24 h (QR range 30–40 mg/kg/24 h), and 20 mg/kg/24 h (QR range was 20–30 mg/kg/24 h), in CF and non-CF patients, respectively.

Among the 98 ciprofloxacin prescriptions, 23 (23.4%) were considered as “mandatory”, 48 (49.0%) were “alternative” and 27 (27.6%) were “unjustified” (Table 4).

Among 23 prescriptions classified as mandatory, 17 children had CF and 6 not. All had microbiologically documentation with P. aeruginosa (Table 4).

Forty-eight prescriptions were classified as “alternative”. Among them, 28 had culture results available (6 due to P. aeruginosa and 22 due to other bacteria) and 20 without. All could have received an alternative antibiotic (Table 5).

27 were classified as “unjustified” and corresponded to any ciprofloxacin prescription that was not indicated according to the clinical situation and/or microbiological results. Among these 27, 10 had culture results available, 4 due to P. aeruginosa susceptible to all known active antibiotics and 6 due to another microorganism. All of these 10 unjustified prescriptions (5 orally and 5 intravenously) were not indicated based on the current clinical situation or microbiological results (Table 6).

Side effect of ciprofloxacin

We did not notice any bone/joint short-term side effects among the 98 children, even 2 weeks after the end of ciprofloxacin therapy.

Discussion

In our study, 76.6% of ciprofloxacin indications were inappropriate, most often (49.0%) because another antibacterial could have been considered and 27.6% did not correspond to validated indications. The American Academy of Pediatrics [6] supports the use of ciprofloxacin in pediatric cystic fibrosis patients with acute pulmonary exacerbation associated with P. aeruginosa infection, while in recent years, recommendations have also included P. aeruginosa osteochondritis, shigellosis, salmonellosis, and C. jejuni infections, prophylaxis during neutropenia, empiric therapy in febrile neutropenic children with cancer, treatment of patients with multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteremia or meningitis, and combination use with other agents to treat multidrug-resistant mycobacterial disease. Although a recent study showed that levofloxacin may represent an effective therapy [15], the American Academy of Pediatrics does not recommend it for first-line therapy of respiratory tract infection in children [10]. The experience of use FQ in fever with neutropenia or in critically ill children has been limited. Sideri’s study [16], including 18 critically ill children, showed that ciprofloxacin might be a useful option for critically ill children without CF. More recently, Sung L et al.[17] has meta-analyzed 740 low-risk fever with neutropenia episodes in 10 studies, which showed 17% to 24% treatment failure with ciprofloxacin monotherapy or FQ combination therapy, but no cases of infectious deaths has been reported and the rates of adverse events were very low. But in our study, we still considered 4 ciprofloxacin combination prescriptions for fever and neutropenia as “unjustified”.

The use of an incorrect dosage was also frequent among children treated with ciprofloxacin. Indeed, in our study, 28 (28.6%) received an incorrect ciprofloxacin dosage. Furthermore, of the 23 pediatric patients in whom ciprofloxacin was prescribed as mandatory, 9 (39.1%) received an incorrect dose (4 received an excessive dose while 5 an insufficient dose). Sermet-Gaudelus et al. suggested that an excessive daily dosage was considered when it was more than 40 mg/kg in non CF patient and an insufficient dosage was considered when it was less than 40 mg/kg/d in CF patients and less than 20 mg/kg/d in non CF patients [18]. The likelihood of FQ drug toxicity may also be affected by inappropriate FQ prescribing. In fact, higher dose and longer duration of FQ therapy have both been associated with a greater risk of adverse events, including emergence of multidrug resistance [19].

The use of FQ has been limited in pediatric infection due to their potential side-effects which have been found to affect cartilage in juvenile animals, resulting in arthropathy [1]. However, in recently controlled, retrospective studies, major arthropathy (as observed in animals) has never been notified in children [4, 5]. In addition, if a musculoskeletal event did occur in the exposed children, it was always minor and always reversible. In recent years, FQ use in children has increased in the United States, but not in France [3]. Few studies have evaluated the appropriate use of FQ prescriptions in children in order to avoid the side effects and their ecological impact [20]. In our study, we did not notice any bone/joint short-term side effects among the 98 children, even 2 weeks after the end of ciprofloxacin therapy, because our observational period was too short or the cases were too small to evaluate the side effects of ciprofloxacin in children use.

Our findings suggest that our current patterns of FQ use can be greatly improved in children in an effort to reduce the spread of FQ resistance. Recently, several studies have showed that about 50%, even up to 70%, of antibiotic usage in hospitals and in emergency departments were inappropriate [21–24], in accordance with our results.

The assistance of a medical microbiologist/infectious diseases specialist in addition to educational presentations as done in adult’s populations have led to 3 to 4-fold sustained reduction of inappropriate prescriptions, but also to a significant improvement in quality of ciprofloxacin prescriptions [25] in accordance with existing guidelines [22].

The most important situation where we need FQ in children is cystic fibrosis and P. aeruginosa infection. Other indications are rare and require individual careful assessment. The limitations of our study were that it was an observational monocentric study and was done within a short period of time. A larger study would have indeed provided more meaningful information. The duration of FQ use was not collected in our study.

Conclusion

In our university hospital, only 23.4% of fluoroquinolones prescriptions were mandatory in children, especially for P. aeruginosa healthcare associated infection. Looking to the ecological risk of fluoroquinolones and the increase consumption in children population, we think that a control program should be developed to control FQ use in children. It could be done with the help of an antimicrobial stewardship team.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

References

Committee on Infectious Diseases: The Use of Systemic Fluoroquinolones. Pediatrics. 2006, 118: 1287-1292.

Adefurin A, Sammons H, Jacqz-Aigrain E, Choonara I: Ciprofloxacin safety in paediatrics: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2011, 96: 874-80. 10.1136/adc.2010.208843.

Chalumeau M, Tonnelier S, D’Athis P, Tréluyer JM, Gendrel D, Bréart G, Pons G, Pediatric Fluoroquinolone Safety Study Investigators: Fluoroquinolone safety in pediatric patients: a prospective, multicenter, comparative cohort study in France. Pediatrics. 2003, 111: e714-9. 10.1542/peds.111.6.e714.

Drossou-Agakidou V, Roilides E, Papakyriakidou-Koliouska P, Agakidis C, Nikolaides N, Sarafidis K, Kremenopoulos G: Use of ciprofloxacin in neonatal sepsis: lack of adverse effects up to one year. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004, 23: 346-9. 10.1097/00006454-200404000-00014.

Yee CL, Duffy C, Gerbino PG, Stryker S, Noel GJ: Tendon or joint disorders in children after treatment with fluoroquinolones or azithromycin. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002, 21: 525-9. 10.1097/00006454-200206000-00009.

American Academy of Pediatrics: Section 4, Antimicrobial agents and related therapy. Fluoroquinolones. Red Book. 2009, 737-738.

Stockmann C, Sherwin CM, Zobell JT, Young DC, Waters CD, Spigarelli MG, Ampofo K: Optimization of anti-pseudomonal antibiotics for cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbations: III. fluoroquinolones. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2013, 48: 211-20. 10.1002/ppul.22667.

Sabharwal V, Marchant CD: Fluoroquinolone use in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006, 25: 257-8. 10.1097/01.inf.0000205799.35780.f3.

Nydert P, Lindemalm S, Nemeth A: Off-label drug use evaluation in paediatrics–applied to ciprofloxacin when used as treatment of cholangitis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011, 20: 393-8. 10.1002/pds.2080.

Bradley JS, Mary Anne Jackson and the Committee on Infectious Diseases: The Use of Systemic and Topical Fluoroquinolones. Pediatrics. 2011, 128: e1034-10.1542/peds.2011-1496.

MacDougall C, Harpe SE, Powell JP, Johnson CK, Edmond MB, Polk RE: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and fluoroquinolone use. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005, 11: 1197-204. 10.3201/eid1108.050116.

Neuhauser MM, Weinstein RA, Rydman R, Danziger LH, Karam G, Quinn JP: Antibiotic resistance among gram-negative bacilli in US intensive care units: implications for fluoroquinolone use. JAMA. 2003, 289: 885-8. 10.1001/jama.289.7.885.

Charbonneau P, Parienti JJ, Thibon P, Ramakers M, Daubin C, du Cheyron D, Lebouvier G, Le Coutour X, Leclercq R, French Fluoroquinolone Free (3F) Study Group: Fluoroquinolone use and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolation rates in hospitalized patients: a quasi experimental study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006, 42: 778-784. 10.1086/500319.

Friedman ND, Kaye KS, Stout JE, McGarry SA, Trivette SL, Briggs JP, Lamm W, Clark C, MacFarquhar J, Walton AL, Reller LB, Sexton DJ: Health care-associated bloodstream infections in adults: a reason to change the accepted definition of community-acquired infections. Ann Intern Med. 2002, 137: 791-7. 10.7326/0003-4819-137-10-200211190-00007.

Bradley JS, Arguedas A, Blumer JL, Saez-Llorens X, Melkote R, Noel GJ: Comparative study of levofloxacin in the treatment of children with community-acquired pneumonia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007, 26: 868-878. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3180cbd2c7.

Sideri G, Kafetzis DA, Vouloumanou EK, Papadatos JH, Papadimitriou M, Falagas ME: Ciprofloxacin in critically ill children. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011, 39: 635-639.

Sung L, Manji A, Beyene J, Dupuis LL, Alexander S, Phillips R, Lehrnbecher T: Fluoroquinolones in Children with Fever and Neutropenia - a Systematic Review of Prospective Trials. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012, 31: 431-435. 10.1097/INF.0b013e318245ab48.

Sermet-Gaudelus I, Ferroni A, Vrielinck S, Lebourgeois M, Chedevergne F, Lenoir G: Anti Pseudomonas aeruginosa antibiotic therapy in cystic fibrosis (exclusion of macrolides). Arch Pediatr. 2006, 13 (1): S30-43. Review. French

Pépin J, Saheb N, Coulombe MA, Alary ME, Corriveau MP, Authier S, Leblanc M, Rivard G, Bettez M, Primeau V, Nguyen M, Jacob CE, Lanthier L: Emergence of fluoroquinolones as the predominant risk factor for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a cohort study during an epidemic in Quebec. Clin Infect Dis. 2005, 41: 1254-60. 10.1086/496986.

Lautenbach E, Larosa LA, Kasbekar N, Peng HP, Maniglia RJ, Fishman NO: Fluoroquinolone utilization in the emergency departments of academic medical centers: prevalence of, and risk factors for, inappropriate use. Arch Intern Med. 2003, 163: 601-5. 10.1001/archinte.163.5.601.

Di Pentima MC, Chan S, Hossain J: Benefits of a pediatric antimicrobial stewardship program at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2011, 128: 1062-70. 10.1542/peds.2010-3589.

Hersh AL, Beekmann SE, Polgreen PM, Zaoutis TE, Newland JG: Antimicrobial stewardship programs in pediatrics. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009, 30: 1211-7. 10.1086/648088.

Levy ER, Swami S, Dubois SG, Wendt R, Banerjee R: Rates and appropriateness of antimicrobial prescribing at an academic children’s hospital, 2007–2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012, 33: 346-53. 10.1086/664761.

Newland JG, Hersh AL: Purpose and design of antimicrobial stewardship programs in pediatrics. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010, 29: 862-3. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181ef2507.

van Hees BC, de Ruiter E, Wiltink EH, de Jongh BM, Tersmette M: Optimizing use of ciprofloxacin: a prospective intervention study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008, 61: 210-13.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/13/245/prepub

Acknowledgement

This work was presented orally in part at the 20th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Disease (ECCMID) 2010, Vienna, Austria (Abstract: n° 1453).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ZTY, JRZ, MP, SB and XN made substantial contributions to conception and design. ZTY, JRZ, FM and SBV participated in acquisition of data. ZTY, JRZ and OL drafted the manuscript. JRZ and OL revised it critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, ZT., Zahar, JR., Méchaï, F. et al. Current ciprofloxacin usage in children hospitalized in a referral hospital in Paris. BMC Infect Dis 13, 245 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-245

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-245