Abstract

Background

Antibiotic resistance is an increasing challenge for health care services worldwide. While up to 90% of antibiotics are being prescribed in the outpatient sector recommendations for the treatment of community-acquired infections are usually based on resistance findings from hospitalized patients. In context of the EU-project called "APRES - the appropriateness of prescribing antibiotic in primary health care in Europe with respect to antibiotic resistance" it was our aim to gain detailed information about the resistance data from Austria in both the scientific and the grey literature.

Methods

A systematic review was performed including scientific and grey literature published between 2000 and 2010. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined and the review process followed published recommendations.

Results

Seventeen scientific articles and 23 grey literature documents could be found. In contrast to the grey literature, the scientific publications describe only a small part of the resistance situation in the primary health care sector in Austria. Merely half of these publications contain data from the ambulatory sector exclusively but these data are older than ten years, are very heterogeneous concerning the observed time period, the number and origin of the isolates and the kind of bacteria analysed. The grey literature yields more comprehensive and up-to-date information of the content of interest. These sources are available in German only and are not easily accessible. The resistance situation described in the grey literature can be summarized as rather stable over the last two years. For Escherichia coli e.g. the highest antibiotic resistance rates can be seen with fluorochiniolones (19%) and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (27%).

Conclusion

Comprehensive and up-to-date antibiotic resistance data of different pathogens isolated from the community level in Austria are presented. They could be found mainly in the grey literature, only few are published in peer-reviewed journals. The grey literature, therefore, is a very valuable source of relevant information. It could be speculated that the situation of published literature is similar in other countries as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The increasing prevalence of antibiotic resistance (AR) is one of the major challenges for the healthcare systems worldwide. Antibiotic resistant infections are associated with a 1.3 to 2-fold increase in mortality compared to antibiotic susceptible infections [1]. If antibiotics become ineffective, infectious diseases will lead to an increase in morbidity and eventually premature mortality [2–4]. Moreover, AR imposes enormous health expenditure from higher treatment costs and longer hospital stays [5–10]. In addition, the development of new generations of antibiotic drugs is stalling [11]. Therefore, restrictive and appropriate use of antibiotics is even more needed to ensure the availability of effective treatment of bacterial infections. While up to 90% of antibiotics are being prescribed to patients in the outpatient sector existing information on the antibiotic resistance pattern is, with exceptions, based on samples from hospitalized patients [12]. Excessive use of antibiotics by humans, mainly due to antibiotic overtreatment of viral infections and in livestock breeding has led to a large output of resistant bacteria into the environment, where resistant bacteria and resistance genes can disseminate [13, 14]. And indeed, the highest bacterial resistances rate was found where antibiotics are used most [12].

Two European initiatives provide valuable information on the topic "antibiotic resistance" in Austria: EARS-Net (formerly EARSS, European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System) [15] and ESAC (European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption) [16]. EARS-Net e.g. performs a continuous surveillance of antimicrobial susceptibility on the basis of laboratory analyses of invasive, blood-culture derived isolates from hospitalized patients. However, the antibiotic resistance pattern of the microbial flora of hospitalized patients differs from that seen in the community and, in addition, the resistance pattern of bacteria in routine primary health care is usually only tested after initial treatment failure [17]. Guidelines for prescribing antibiotics to patients at a community level should, therefore, be based on empirical and up to date evidence about antibiotic resistance of bacteria circulating in the community. Ideally, continuous surveillance of resistance patterns and antibiotic consumption in the outpatient setting should be carried out to detect changes.

In the year 2010 an EU-project called "APRES - the appropriateness of prescribing antibiotics in primary health care in Europe with respect to antibiotic resistance" started in nine European countries including Austria. One aim of this cross-sectional project is a systematic analysis of antibiotic resistance pattern of two key-bacteria at the community level. The analysis should be the basis for specific regional and national recommendations concerning the antibiotic prescribing behaviour of physicians in primary health care.

In the context of this EU-study we have undertaken a systematic literature review of all scientific papers and also of grey and non-English literature concerning the resistance pattern for the primary care sector in Austria in order to summarize existing facts and knowledge. It was our aim to assess strengths and weaknesses of the resistance situation at the community level described for Austria and to identify the sources and origin of the data published.

Methods

Study selection

A systematic literature review was performed of all available literature published between the 1st of January 2000 and the 31st January 2011. For the review process we followed the recommendations of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses) statement [18] as it is described in the additional file 1. Three necessary inclusion criteria for the relevant literature were defined: First, the content has to deal with antibiotic resistance. Second, the resistance data have to be sampled in the ambulatory or community sector in humans and third, in Austria. We searched the scientific literature as well as the grey literature.

All types of indexed scientific literature were included. The bacteria included were Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Klebsiella pneumoniae for the respiratory tract, Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella spp., Staphylococcus saphrophyticus for the urinary tract and Staphylococcus aureus. Literature containing resistance data from the hospital setting only and the literature not describing the origin either from hospital or primary care setting of the samples were excluded. The language of the literature included was English and German.

For the specification of the "grey" literature we used the definition of the Luxembourg Convention on Grey Literature: "Grey literature is that which is produced on all levels of government, academics, business, and industry in print and electronic formats but which is not controlled by commercial publishers." [19] Essentially, grey literature includes documents that have not been formally published in a peer-reviewed indexed format.

The literature search via electronic searches as well as the review process was carried out by two researchers (KH and GW) for the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreement within the review process was resolved by discussion with the fourth author (MM).

Search strategy

The literature search was performed during the period from April 1, 2010 until March 29, 2011.

For the scientific literature the databases and search engines PubMed, Medline and Embase were used. Search terms were the MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms "primary health care" OR "ambulatory care" AND "drug Resistance, Bacterial" AND "Austria" which were combined with the search terms "antibiotic resistance" OR "antimicrobial resistance", "primary care" OR "outpatient" OR "general practice" OR "community", in different combinations. According to the terms in English we used the corresponding German terms "Antibiotika", "Resistenzen", "Allgemeinmedizin", "niedergelassener Bereich" and "Österreich". Additionally, manual searches of the references of relevant articles including reviews were performed.

The search strategy for the grey literature was conducted via the search engines Google (http://www.google.at) and Google Scholar (http://scholar.google.at); in addition a systematic search on websites of institutions and organizations dealing with the sampling and determination of bacteria like regional laboratories for infectious diseases, reference centres or organizations that are responsible for public health like the Ministry of Health and linked facilities was performed. The search terms used were the same as for the scientific literature.

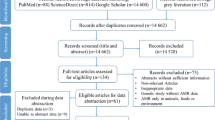

The exclusion process for the scientific literature was a three step process. The first step was the rejection of the duplicates, followed by the exclusion due to screening the title and abstract of papers identified; in the third step the papers were excluded by reading the full text of the papers, each of which was independently reviewed for eligibility. The exclusion process for the grey literature was performed as a three step process too by reading the "Google" title of the link and the short description first, followed by reading the full text of the relevant literature.

Finally, we allocated the literature that met all inclusion criteria into a "high quality" group (reports, government documents, recommendations of Austrian Societies, publications not published in an indexed journal) with respect to the method section described in this literature and a "low quality group" (interviews, official invitations, meeting notes) as recommended by Dobbins et al [20]. Only the "high quality" grey literature was included into this review.

Data extraction

The outcome data extracted were: Numbers and characteristics of the included studies, bacteria types described, sampling location in Austria and general antibiotic resistance findings. Further, the sources of the data were documented.

Results

After the rejection of the duplicate papers a total of 82 potential scientific papers were identified of which 9 were excluded on the basis of the year published and 40 were excluded after reading the abstract and title. Further 16 papers were excluded after reading the full text. Most of the papers were excluded because the reported incidence of resistance data was exclusively from the hospital sector in Austria (EARS-Net) or other countries than Austria. Seventeen papers were included into the final review. Figure 1 shows the "PRISMA Flow Diagram" for the scientific literature results [18]. The grey literature search strategy yielded e.g. 3,840 potential relevant links on March, 29 2011 by using the combination of the search terms "Antibiotikaresistenzen" AND "Österreich" AND "niedergelassener Bereich" in Google.at. After the three step review procedure 23 high quality publications remained of which 21 are resistance reports (19 regional reports from different years published between 2002 and 2011 and two national reports of the years 2008 and 2009). Most of the excluded literature enunciated treatment recommendations of infectious diseases for the ambulatory sector by referencing to data from the hospital sector.

Table 1 summarizes the basic characteristics and selected resistance findings of the final 17 scientific papers. Nine [21–29] out of the 17 scientific papers describe the resistance pattern of certain bacteria for the ambulatory sector only by referencing to four data sources, the Alexander-Project [22, 27], the PROTEKT (Prospective Resistant Organism Tracking and Epidemiology for the Ketolide Telithromycin) surveillance study [21, 23, 25], the ECO-SENS (International Survey of the Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Urinary Pathogens) project [24, 26, 29] and the ARESC (Antimicrobial Resistance Epidemiological Survey on Cystitis) study [28]. Eight of these nine publications describe the resistance situation in Austria before the year 2001. The reported resistance patterns of the analysed bacteria in the other publications are based on isolates from both the hospital and the outpatient sector in different proportions.

Six articles show the resistance pattern of E. coli, ESBL-producing E. coli and other bacteria related to community-acquired uncomplicated urinary tract infections [24, 26, 28–31], eight the resistance pattern of the bacteria included for community-acquired respiratory tract infections [21–23, 25, 27, 32–34], further two are dealing with the MRSA situation in Austria [35, 36] and one article is a "letter to the editor" with an overview of multiple bacteria [37]. No overall conclusion of the current resistance situation in the ambulatory sector in Austria can be gathered out of these different studies due to the differences in sampling settings, inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study population, time periods, bacteria analysed and the methodology used. Moreover, the determination of the resistance rates in Austria was conducted using the CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute) standard. Within this standard there has been a change in the antimicrobial MIC breakpoint in 2008 which means that most data before and after 2008 are not comparable [38].

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the basic characteristics and selected resistance findings of the 23 high quality grey literature documents of which only the isolates from the primary health care sector included into the reports are described. The resistance findings included are contained in several reports and their updates since the year 2008 separately for the ambulatory and the hospital sector. The key-bacteria analysed for the urinary and respiratory tract are the same among the reports. The Austrian resistance reports (AURES) of the years 2008 and 2009 e.g. include the chapter "Resistance report for selected non-invasive microbial pathogens" which summarize the data from the ambulatory sector of several large microbiology laboratories from all over Austria; a change in the resistance pattern of the bacteria included can be observed in certain regions over several years (table 3). While the change in the CLSI standard in 2008 has to be considered for these resistance reports as well the overall resistance situation in the primary care sector in Austria for e.g. E. coli is summarized as following: "The percentage of the ESBL-producing E. coli is with 6% stable over the last two years in the primary care sector. The highest antibiotic resistance rates for E. coli and ESBL-producing E. coli can be seen with fluorochinolones (19%/85%) and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (27%/82%)."[39]

All resistance reports included are published in German only and on special websites.

Discussion

This review provides the most comprehensive and up to date information on the pattern of AR at the community level in Austria. This has been achieved by a thorough search of both the scientific and grey literature.

Our analysis shows that the seventeen scientific publications included describe only a small part of the resistance situation in the primary health care sector in Austria (table 1). Half of these publications contain data from the ambulatory sector only but are older than ten years. Moreover, the included scientific literature is very heterogeneous concerning the observed time period, the number and origin of the isolates and the kind of bacteria analysed.

In contrast, the grey literature yields more substantial information on the content of interest (tables 2 and 3). Mainly the "resistance reports" (Resistenzberichte) contain comprehensive and up-to-date resistance data from the ambulatory level. Since 2008, the AURES report in particular is the only source which provides comprehensive, structured and nationwide data on a yearly basis from isolates obtained exclusively at the primary care sector. The resistance situation described can be summarized as rather stable over the last two years. A comparison of the resistance situations can be drawn on a regional and on a national level (table 3). This literature is at the moment the best available source of ambulatory resistance data; however, the data are not covering all regions of Austria. Further, the reports are available in German only, are accessible on certain specific websites only and are not published in indexed journals. Therefore, it is nearly impossible for someone who cannot speak German or is not familiar with the website address to find a comprehensive source of information about the current resistance situation in the primary health care sector in Austria. Moreover, the methodology for the determination of resistance differs between Austrian counties and European countries which, hopefully, will improve due to the EUCAST (European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing) efforts to harmonize the MIC breakpoints for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bacteria in Europe [40]. This could be an obstacle for comparative studies which are based on systematic literature searches from different countries or for finding adequate sources to describe the status quo in Austria. Unfortunately, the results from the promising international studies (Alexander project and PROTEKT study)[41] of the years 1999 and 2000 that dealt with the resistance pattern of bacteria responsible for community-acquired infections of the respiratory tract have not been translated into regular national or international surveillance systems.

In contrast, comprehensive and current antibiotic resistance data from the hospital sector or outpatient antibiotic consumption data in Austria are easy to find in the scientific literature due to the longstanding partnership of Austria with the EARS-Net and ESAC network. These standardized data were collected nationwide and published regularly [42, 43]. This could be the reason that, at the moment, all recommendations available for the treatment of community-acquired infectious diseases for the primary health care sector still are based on resistance data derived from the hospital sector [44]. Examples are the brochure of the Austrian Antibiotic Stewardship Group (ABS) for the ambulatory sector or the latest expert consensus of the Austrian Society of Infectious Diseases concerning Antibiotic treatment in primary health care [45, 46]. It should be mentioned that first steps towards a resistance-register for non-invasive isolates from the primary health care sector in Austria are already under way. The collection and reporting of non-invasive isolates and their resistances in the regional and the national resistance reports in a structured and systematic way could be the starting point. Also the ABS group is advancing this issue [47, 48].

The strengths of this review are its focus on the outpatient setting in Austria and its comprehensiveness by the inclusion of both the scientific and the grey literature. In fact, for our purpose the data contained in the grey literature prove very valuable in achieving our aim of comprehensiveness and reduces publication and selection bias. It could be speculated that the situation of published literature is similar in other countries as well. However, recent studies have examined the impact of the inclusion of the grey literature in systematic reviews to describe the status quo of a situation in more detail [49–51]. Especially, since a Cochrane update was published in 2004 to highlight the importance of widespread literature search strategies for public health interventions including the grey literature for systematic reviews [52] the number of reviews which include grey literature is growing constantly in many health related sectors [53–60].

The limitations of this literature review are the reliance on previously published research results. Even more difficult is the reliance on the grey literature found due to the non hierarchic search results with the search engine Google. Moreover, in this review we compared the scientific and the grey literature and draw conclusions on their comprehensiveness and on the public health relevance of their content. Since the scientific papers were independently peer-reviewed and the grey literature was published by organizations without that review process this may affect the methodological quality and therefore, the scientific level of evidence. In addition, it is not possible to directly compare the resistance data described in the scientific and grey literature: in the scientific literature the resistance data are mainly analysed for specific diseases like e.g. uncomplicated urinary tract infections in a defined group of patients, in the grey literature the resistance data reported are the result of all isolates analysed for one specific bacterium regardless of a given disease.

Conclusion

In this review, comprehensive and up-to-date antibiotic resistance data of different pathogens, isolated from the primary care level in Austria, are presented. They could be found mainly in the grey literature, only few are published in peer-reviewed journals. The grey literature, therefore, is a very valuable source of relevant information and might reveal possibilities for further research.

Based on these findings we recommend collecting and publishing also the non-invasive resistance findings on a regular basis in indexed journals like it is done in the EARS-Net and ESAC network.

References

Cosgrove SE, Carmeli Y: The impact of antimicrobial resistance on health and economic outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2003, 36 (11): 1433-1437. 10.1086/375081.

Livermore DM: Bacterial resistance: origins, epidemiology, and impact. Clin Infect Dis. 2003, 36 (Suppl 1): 11-23.

Levy SB: Antibiotic resistance-the problem intensifies. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005, 57 (10): 1446-1450. 10.1016/j.addr.2005.04.001.

Harbarth S, Samore MH: Antimicrobial resistance determinants and future control. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005, 11 (6): 794-801.

Cosgrove SE: The relationship between antimicrobial resistance and patient outcomes: mortality, length of hospital stay, and health care costs. Clin Infect Dis. 2006, 42 (Suppl 2): S82-89.

Mauldin PD, Salgado CD, Hansen IS, Durup DT, Bosso JA: Attributable hospital cost and length of stay associated with health care-associated infections caused by antibiotic-resistant gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009, 54 (1): 109-115.

Okeke IN, Laxminarayan R, Bhutta ZA, Duse AG, Jenkins P, O'Brien TF, Pablos-Mendez A, Klugman KP: Antimicrobial resistance in developing countries. Part I: recent trends and current status. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005, 5 (8): 481-493. 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70189-4.

Okeke IN, Klugman KP, Bhutta ZA, Duse AG, Jenkins P, O'Brien TF, Pablos-Mendez A, Laxminarayan R: Antimicrobial resistance in developing countries. Part II: strategies for containment. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005, 5 (9): 568-580. 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70217-6.

Smith RD: Assessing the macroeconomic impact of a healthcare problem: the application of computable general equilibrium analysis to antimicrobial resistance. Journal of Health Economics. 2005, 24: 1055-1075. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2005.02.003.

Mossialos E, Morel CM, Edwards S, Berenson J, Gemmill-Toyama M, Brogan D: Policies and incentives for promoting innovation in antibiotic research. 2010, WHO, Copenhagen

Kaplan W, Laing R: Priority medicines for Europe and the World. 2004, WHO, Geneva

Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R, Elseviers M: Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet. 2005, 365 (9459): 579-587.

Murray BE: Problems and dilemmas of antimicrobial resistance. Pharmacotherapy. 1992, 12 (6 Pt 2): 86S-93S.

Summers AO: Generally overlooked fundamentals of bacterial genetics and ecology. Clin Infect Dis. 2002, 34 (Suppl 3): 85-92.

Bronzwaer SL, Goettsch W, Olsson-Liljequist B, Wale MC, Vatopoulos AC, Sprenger MJ: European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (EARSS): objectives and organisation. Euro Surveill. 1999, 4 (4): 41-44.

Vander Stichele RH, Elseviers MM, Ferech M, Blot S, Goossens H: European surveillance of antimicrobial consumption (ESAC): data collection performance and methodological approach. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004, 58 (4): 419-428. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02164.x.

Magee JT, Pritchard EL, Fitzgerald KA, Dunstan FD, Howard AJ: Antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance in community practice: retrospective study, 1996-8. BMJ. 1999, 319 (7219): 1239-1240.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009, 339: b2535-10.1136/bmj.b2535.

Luxembourg Convention on Grey Literature. Perspectives on the Design and Transfer of Scientific and Technical Information. Third Conference on Grey Literature. [http://www.greynet.org/]

Dobbins M, Robeson P: A Methodology for Searching the Grey Literature for Effectiveness Evidence Syntheses related to Public Health. 2006, The Public Health Agency of Canada

Canton R, Loza E, Morosini MI, Baquero F: Antimicrobial resistance amongst isolates of Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus in the PROTEKT antimicrobial surveillance programme during 1999-2000. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002, 50 (Suppl S1): 9-24.

Cizman M: The use and resistance to antibiotics in the community. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003, 21 (4): 297-307. 10.1016/S0924-8579(02)00394-1.

Felmingham D, Reinert RR, Hirakata Y, Rodloff A: Increasing prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae from the PROTEKT surveillance study, and compatative in vitro activity of the ketolide, telithromycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002, 50 (Suppl S1): 25-37.

Graninger W: Pivmecillinam--therapy of choice for lower urinary tract infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003, 22 (Suppl 2): 73-78.

Hoban D, Felmingham D: The PROTEKT surveillance study: antimicrobial susceptibility of Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis from community-acquired respiratory tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002, 50 (Suppl S1): 49-59.

Kahlmeter G: An international survey of the antimicrobial susceptibility of pathogens from uncomplicated urinary tract infections: the ECO.SENS Project. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003, 51 (1): 69-76. 10.1093/jac/dkg028.

Schito GC, Debbia EA, Marchese A: The evolving threat of antibiotic resistance in Europe: new data from the Alexander Project. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000, 46 (Suppl T1): 3-9.

Schito GC, Naber KG, Botto H, Palou J, Mazzei T, Gualco L, Marchese A: The ARESC study: an international survey on the antimicrobial resistance of pathogens involved in uncomplicated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009, 34 (5): 407-413. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.04.012.

Kahlmeter G, Menday P, Cars O: Non-hospital antimicrobial usage and resistance in community-acquired Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003, 52 (6): 1005-1010. 10.1093/jac/dkg488.

Auer S, Wojna A, Hell M: Oral treatment options for ambulatory patients with urinary tract infections caused by extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010, 54 (9): 4006-4008. 10.1128/AAC.01760-09.

Prelog M, Fille M, Prodinger W, Grif K, Brunner A, Wurzner R, Zimmerhackl LB: CTX-M-1-related extended-spectrum beta-lactamases producing Escherichia coli: so far a sporadic event in Western Austria. Infection. 2008, 36 (4): 362-367. 10.1007/s15010-008-7309-7.

Buxbaum A, Forsthuber S, Graninger W, Georgopoulos A: Comparative activity of telithromycin against typical community-acquired respiratory pathogens. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003, 52 (3): 371-374. 10.1093/jac/dkg359.

Hoenigl M, Fussi P, Feierl G, Wagner-Eibel U, Leitner E, Masoud L, Zarfel G, Marth E, Grisold AJ: Antimicrobial resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Southeast Austria, 1997-2008. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010, 36 (1): 24-27. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.03.001.

Schito GC, Georgopoulos A, Prieto J: Antibacterial activity of oral antibiotics against community-acquired respiratory pathogens from three European countries. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002, 50 (Suppl): 7-11.

Krziwanek K, Luger C, Sammer B, Stumvoll S, Stammler M, Sagel U, Witte W, Mittermayer H: MRSA in Austria--an overview. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008, 14 (3): 250-259. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01896.x.

Krziwanek K, Metz-Gercek S, Mittermayer H: Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 from human patients, upper Austria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009, 15 (5): 766-769. 10.3201/eid1505.080326.

Badura A, Feierl G, Kessler HH, Grisold A, Masoud L, Wagner-Eibel U, Marth E: Multidrug-resistant bacteria in southeastern Austria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007, 13 (8): 1256-1257.

Anderson NL, Bruno LC, Chapin KC, Cullen S, Daly JA, Eusebio R: Consensus Guidelines Developed for Streamlined Quality Control on Commercial Microbial Identification Systems. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. LABMEDICINE. 2008, 39:

Apfalter P, Allerberger F, Fluch G, Oegger G: Resistenzbericht Österreich. AURES 2009. Antibiotikaresistenz und Verbrauch antimikrobieller Substanzen in Österreich. 2010, Bundesministerium für Gesundheit, Wien

Kahlmeter G, Brown DF, Goldstein FW, MacGowan AP, Mouton JW, Osterlund A, Rodloff A, Steinbakk M, Urbaskova P, Vatopoulos A: European harmonization of MIC breakpoints for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003, 52 (2): 145-148. 10.1093/jac/dkg312.

Felmingham D, Gruneberg RN: A multicentre collaborative study of the antimicrobial susceptibility of community-acquired, lower respiratory tract pathogens 1992-1993: the Alexander Project. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996, 38 (Suppl A): 1-57.

EARS-Net Reports. [http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/activities/surveillance/EARS-Net/Pages/index.aspx]

ESAC database. [http://app.esac.ua.ac.be/public/]

Metz-Gercek S, Maieron A, Strauss R, Wieninger P, Apfalter P, Mittermayer H: Ten years of antibiotic consumption in ambulatory care: trends in prescribing practice and antibiotic resistance in Austria. BMC Infect Dis. 2009, 9: 61-10.1186/1471-2334-9-61.

Allerberger F, Apfalter P, Burgmann H, Gareis R, Janata O, Krause R, Lechner A, Mittermayer H, Wechsler-Fördös A: ABSantibioticstewardship im Niedergelassenen Bereich. Diagnose und Therapie von Infektionskrankheiten. 2010, ABSGROUP GmbH, Wien

Österreichische Gesellschaft für Infektionserkrankungen: Antiinfektiva - Behandlung von Infektionen. Arznei & Vernunft. 2010

Allerberger F, Frank A, Gareis R: Antibiotic stewardship through the EU project "ABS International". Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2008, 120 (9-10): 256-263. 10.1007/s00508-008-0966-9.

Allerberger F, Gareis R, Jindrak V, Struelens MJ: Antibiotic stewardship implementation in the EU: the way forward. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2009, 7 (10): 1175-1183. 10.1586/eri.09.96.

Conn VS, Valentine JC, Cooper HM, Rantz MJ: Grey literature in meta-analyses. Nurs Res. 2003, 52 (4): 256-261. 10.1097/00006199-200307000-00008.

Helmer D, Savoie I, Green C, Kazanjian A: Evidence-based practice: extending the search to find material for the systematic review. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2001, 89 (4): 346-352.

McAuley L, Pham B, Tugwell P, Moher D: Does the inclusion of grey literature influence estimates of intervention effectiveness reported in meta-analyses?. Lancet. 2000, 356 (9237): 1228-1231. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02786-0.

Howes F, Doyle J, Jackson N, Waters E: Evidence-based public health: The importance of finding 'difficult to locate' public health and health promotion intervention studies for systematic reviews. J Public Health (Oxf). 2004, 26 (1): 101-104. 10.1093/pubmed/fdh119.

Hartling L, McAlister FA, Rowe BH, Ezekowitz J, Friesen C, Klassen TP: Challenges in systematic reviews of therapeutic devices and procedures. Ann Intern Med. 2005, 142 (12 Pt 2): 1100-1111.

Blackhall K: Finding studies for inclusion in systematic reviews of interventions for injury prevention the importance of grey and unpublished literature. Inj Prev. 2007, 13 (5): 359-10.1136/ip.2007.017020.

Hopewell S, McDonald S, Clarke M, Egger M: Grey literature in meta-analyses of randomized trials of health care interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, MR000010-2

Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Gulliver A: Plenty of activity but little outcome data: a review of the "grey literature" on primary care anxiety and depression programs in Australia. Med J Aust. 2008, 188 (12 Suppl): S103-106.

Willis-Shattuck M, Bidwell P, Thomas S, Wyness L, Blaauw D, Ditlopo P: Motivation and retention of health workers in developing countries: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008, 8: 247-10.1186/1472-6963-8-247.

Zechmeister I, Kilian R, McDaid D: Is it worth investing in mental health promotion and prevention of mental illness? A systematic review of the evidence from economic evaluations. BMC Public Health. 2008, 8: 20-10.1186/1471-2458-8-20.

Borschmann R, Hogg J, Phillips R, Moran P: Measuring self-harm in adults: A systematic review. Eur Psychiatry. 2011

Bisits Bullen PA: The positive deviance/hearth approach to reducing child malnutrition: systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2011

Mittermayer H, Metz-Gercek S, Allerberger F: Resistenzbericht Österreich. AURES 2008. Antibiotikaresistenz und Verbrauch antimikrobieller Substanzen in Österreich. 2009, Bundesministerium für Gesundheit, Wien

Wojna A: Resistenzreport 2009. Zusammenfassung der lokalen Resistenzdaten. 2010, Abt. f. Mikrobiologie, Med.-chem. Labor Dr. Mustafa, Labor Dr. Richter OG, Salzburg

Wojna A: Resistenzreport 2008. Zusammenfassung der lokalen Resistenzdaten. 2009, Abt. f. Mikrobiologie, Med.-chem. Labor Dr. Mustafa, Labor Dr. Richter OG, Salzburg

Wojna A: Resistenzbericht 2007. 2008, Abt. f. Mikrobiologie, Med.-chem. Labor Dr. Mustafa, Labor Dr. Richter OG, Salzburg

Wojna A: Resistenzbericht 2006. 2007, Abt. f. Mikrobiologie, Med.-chem. Labor Dr. Mustafa, Labor Dr. Richter OG, Salzburg

Wojna A: Resistenzbericht 2005. 2006, Abt. f. Mikrobiologie, Med.-chem. Labor Dr. Mustafa, Labor Dr. Richter OG, Salzburg

Wojna A: Resistenzbericht 2004. 2005, Abt. f. Mikrobiologie, Med.-chem. Labor Dr. Mustafa, Labor Dr. Richter OG, Salzburg

Wojna A: Resistenzbericht 2003. 2004, Abt. f. Mikrobiologie, Med.-chem. Labor Dr. Mustafa, Labor Dr. Richter OG, Salzburg

Wojna A: Resistenzbericht 2002. 2003, Abt. f. Mikrobiologie, Med.-chem. Labor Dr. Mustafa, Labor Dr. Richter OG, Salzburg

Feierl G, Buzina W, Masoud-Landgraf L: Resistenzbericht 2010. 2011, Institut für Hygiene, Mikrobiologie und Umweltmedizin, Medizinische Universität Graz, Labor für Medizinische Bakteriologie und Mykologie, Graz

Feierl G, Buzina W: Resistenzbericht 2009. 2010, Institut für Hygiene, Mikrobiologie und Umweltmedizin, Medizinische Universität Graz, Labor für Medizinische Bakteriologie und Mykologie, Graz

Feierl G, Buzina W: Resistenzbericht 2008. 2009, Institut für Hygiene, Mikrobiologie und Umweltmedizin, Medizinische Universität Graz, Labor für Medizinische Bakteriologie und Mykologie, Graz

Prein K, Fürpass T: Resistenzbericht 2009 aus dem Einsendegut des Bakt. Labors im LKH Leoben. 2010, LKH Leoben, Pathologisches Institut, Bakteriologisches Labor, Leoben

Prein K, Fürpass T: Resistenzbericht 2007 aus dem Einsendegut des Bakt. Labors im LKH Leoben. 2008, LKH Leoben, Pathologisches Institut, Bakteriologisches Labor, Leoben

Prein K: Resistenzbericht 2005 aus dem Einsendegut des Bakt. Labors im LKH Leoben. 206, LKH Leoben, Pathologisches Institut, Bakteriologisches Labor, Leoben

Prein K: Resistenzbericht 2004 aus dem Einsendegut des Bakt. 2005, Labors im LKH Leoben. LKH Leoben, Pathologisches Institut, Bakteriologisches Labor, Leoben

Prein K: Resistenzbericht 2003 aus dem Einsendegut des Bakt. 2004, Labors im LKH Leoben. LKH Leoben, Pathologisches Institut, Bakteriologisches Labor, Leoben

Fille M, Hausdorfer J, Weiss G, Lass-Flörl C: Resistenzbericht 2009. Resistenzverhalten von Bakterien und Pilzen gegen Antibiotika und Antimykotika. 2010, Sektion Hygiene und Medizinische Mikrobiologie und Universitätsklinik für Innere Medizin I, Klinische Infektiologie und Immunologie, Medizinische Universität Innsbruck, Innsbruck

Fille M, Hausdorfer J, Weiss G, Lass-Flörl C: Resistenzbericht 2008. Resistenzverhalten von Bakterien und Pilzen gegen Antibiotika und Antimykotika. 2009, Sektion Hygiene und Medizinische Mikrobiologie und Universitätsklinik für Innere Medizin I, Klinische Infektiologie und Immunologie, Medizinische Universität Innsbruck, Innsbruck

Hell M: ESBL-producing E.coli in uncomplicated UIT - regional and Austria-wide update and evaluation of treatment options. Hyg Med. 2010, 35 (1&2): 26-31.

Grisold A: Das Antibiogramm: Indikation - Interpretation - Qualität. [http://infektiologie-hygiene.universimed.com/artikel/das-antibiogramm-indikation-%E2%80%93-interpretation-%E2%80%93-qualit%C3%A4t]

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/11/330/prepub

Acknowledgements and Funding

This work was financially supported in part by the Seventh EU Framework Programme "APRES - The appropriateness of prescribing antibiotics in primary health care in Europe with respect to antibiotic resistance" (grant agreement number 223083).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

KH and GW performed the literature search; KH performed the extraction of the data and drafted the initial manuscript, GW helped with the extraction of the grey literature data; MM conceptualized the study and helped with data interpretation; PA and MM critically revised the manuscript for important content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12879_2011_1661_MOESM1_ESM.DOC

Additional file 1: PRISMA 2009 checklist. Checklist including relevant page numbers for identifying various components of the review. (DOC 68 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoffmann, K., Wagner, G., Apfalter, P. et al. Antibiotic resistance in primary care in Austria - a systematic review of scientific and grey literature. BMC Infect Dis 11, 330 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-11-330

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-11-330