Abstract

Background

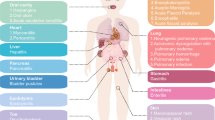

Bartonella tamiae, a newly described bacterial species, was isolated from the blood of three hospitalized patients in Thailand. These patients presented with headache, myalgia, anemia, and mild liver function abnormalities. Since B. tamiae was presumed to be the cause of their illness, these isolates were inoculated into immunocompetent mice to determine their relative pathogenicity in inducing manifestations of disease and pathology similar to that observed in humans.

Methods

Three groups of four Swiss Webster female mice aged 15-18 months were each inoculated with 106-7 colony forming units of one of three B. tamiae isolates [Th239, Th307, and Th339]. A mouse from each experimental group was sampled at 3, 4, 5 and 6 weeks post-inoculation. Two saline inoculated age-matched controls were included in the study. Samples collected at necropsy were evaluated for the presence of B. tamiae DNA, and tissues were formalin-fixed, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and examined for histopathology.

Results

Following inoculation with B. tamiae, mice developed ulcerative skin lesions and subcutaneous masses on the lateral thorax, as well as axillary and inguinal lymphadenopathy. B. tamiae DNA was found in subcutaneous masses, lymph node, and liver of inoculated mice. Histopathological changes were observed in tissues of inoculated mice, and severity of lesions correlated with the isolate inoculated, with the most severe pathology induced by B. tamiae Th239. Mice inoculated with Th239 and Th339 demonstrated myocarditis, lymphadenitis with associated vascular necrosis, and granulomatous hepatitis and nephritis with associated hepatocellular and renal necrosis. Mice inoculated with Th307 developed a deep dermatitis and granulomas within the kidneys.

Conclusions

The three isolates of B. tamiae evaluated in this study induce disease in immunocompetent Swiss Webster mice up to 6 weeks after inoculation. The human patients from whom these isolates were obtained had clinical presentations consistent with the multi-organ pathology observed in mice in this study. This mouse model for B. tamiae induced disease not only strengthens the causal link between this pathogen and clinical illness in humans, but provides a model to further study the pathological processes induced by these bacteria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bartonella bacteria are small, fastidious, aerobic, Gram negative coccobacilli in the family Bartonellaceae, class Alphaproteobacteria. As of 2009 there are 24 named or proposed species in the genus [1], and over the last decade Bartonella bacteria have repeatedly emerged as a cause of human illness globally [2–6]. Infections with these bacteria are generally acquired from zoonotic sources such as host reservoir animals, or from hematophagous arthropods [1]. Either immunocompetent or immunocompromised people may become ill due to infections from Bartonella bacteria [7]. The two Bartonella species most commonly recognized as causing human illness are Bartonella henselae, the agent of 'cat scratch disease', and B. quintana, which caused numerous cases of trench fever in soldiers during World War I, and which today more typically infects homeless people, resulting in endocarditis or bacillary angiomatosis [8, 9]. In South America, the lesser known though more virulent Bartonella bacilliformis causes Oroya fever and verruga peruana in humans, and infected patients may develop a severe, life-threatening hemolytic anemia [8].

Along with increasing awareness of Bartonella bacteria as emerging pathogens has come an increased interest in determining the mechanisms of pathogenesis of these microorganisms [10]. One of the primary impediments to our understanding of the infection and disease process elicited by these bacteria is the inability of researchers to establish suitable animal models for study [11]. Attempts to infect both immunocompetent and immunocompromised laboratory mice with various species of Bartonella bacteria have met with limited success [12–15]. Bartonella bacteria in these models tend to be quickly cleared by the immune system, and though the kinetics of antibody response and aspects of cellular and humoral immunity have been determined [16–18], animal models that reproduce clinical manifestations of disease observed in humans remain elusive. The natural reservoirs for B. henselae and B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii are cats and dogs (canines), respectively, and these animals can serve as models for Bartonella bacteria infection and disease processes [19–21]. However, though it may be more biologically appropriate at times to use natural hosts to study Bartonella bacteria induced pathogenesis, developing a mouse model for disease is desirable due to the widespread availability of murine immunological reagents and selective mutant strains of mice.

A recent success in developing an animal model for Bartonella induced disease was the inoculation of the human pathogen B. henselae into C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice, which produced lymphadenopathy of some duration [22]. These mice did not develop granulomas within the popliteal lymph node, and lymphadenopathy persisted in the near absence of detectable, viable bacteria, both in the lymph node and systemically [22], characteristics which also occur in human 'cat scratch disease', and which were reproduced in this mouse model of bartonellosis.

The present study was undertaken to establish the parameters for experimental inoculation of immunocompetent Swiss Webster mice, aged 15-18 months, with the suspected human pathogen B.tamiae [23]. Subcutaneous inoculation of three B. tamiae isolates into mice elicited a variety of severe histopathological changes and immune responses up to 6 weeks after inoculation. Our observations establish a murine model for B.tamiae induced disease and serve to implicate B. tamiae as a causative agent of human illness in Thailand.

Methods

Inoculation of mice

Specific pathogen free, outbred Swiss Webster female mice, aged 15-18 months, were used for this study. Mice were obtained from a colony of Swiss Webster mice maintained at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Vector-Borne Diseases (CDC/DVBD), Fort Collins, Colorado, USA, an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) accredited facility. Work with the mice was approved by, and conducted under the supervision of the DVBD Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee [protocol # 07-012], in compliance with the guidelines set forth by the Animal Welfare Act (1966) of the United States of America, with regulatory oversight by the United States Public Health Service.

Bacteria for the mouse inoculations were grown on heart infusion agar plates supplemented with 10% rabbit blood [23], in a 5% CO2 incubator at 35°C. Bacterial colonies were harvested into phosphate buffered saline 5 days after plating, and stock suspensions were frozen at -80°C until thawed for inoculation. Aliquots of the frozen stock for each isolate were titrated to verify the inoculated dose. The in vitro bacterial passage history for each of the three B. tamiae isolates is detailed in Table 1[23, 24], and does not include the preparation of the stocks described above.

All experimental mice were inoculated subcutaneously along the midline of the scruff of the neck with between 106 and 107 colony forming units of one of three B. tamiae isolates (Th239, Th307, or Th339) [23]. Three groups of four mice were chosen from the available pool of age matched female mice. Each group was randomly assigned to be inoculated with one of the three available B. tamiae isolates, such that four mice were inoculated for each of the three isolates [n = 12 experimental mice]. Two age-matched female mice were subcutaneously inoculated with saline to serve as controls. Experimental mice were group housed by isolate for the duration of the study, and control mice were held separately from experimental mice. One mouse per isolate group was sacrificed at 3, 4, 5, and 6 weeks post-inoculation (n = 1 mouse per timepoint for each isolate). All of the following tissues were sampled from each mouse, to include both experimental and control mice: blood, spleen, liver, lymph node(s), and kidney. Lymph nodes collected included axillary, brachial, inguinal, popliteal, and cervical nodes, generally in pairs. Lymph nodes were pooled for testing by PCR. Hearts were collected from mice during weeks 4 and 5 post-inoculation (n = 6 hearts total; 4 experimental and 2 control mice). Control mice were sacrificed at 4 and 5 weeks post-inoculation.

Gross observations

Mice were examined by visual inspection and palpation in the weeks following inoculation. Development of ulcerations and formation of subcutaneous masses was noted, as were the location and number of skin lesions. Enlargement of axillary and inguinal lymph nodes was monitored by palpation, with reference to healthy, saline inoculated control mice.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection of Bartonella DNA in tissues

Genomic DNA was extracted from tissues and blood sampled from Swiss Webster mice sacrificed at 3, 4, 5, and 6 weeks after inoculation with three B.tamiae isolates, and from saline inoculated control mice. A 200 ul sample of blood and 10-30 mg each of various tissues (lymph nodes, liver, spleen, kidney, and subcutaneous masses) from each mouse was subjected to DNA extraction using the manufacturer's blood or tissue protocol as outlined in the QIAamp DNA Mini kit handbook (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Extracted DNA was stored at -20° C until tested.

B. tamiae DNA in samples was detected by PCR using Bartonella specific primers targeting the gltA (citrate synthase gene) [25], and 16S-23 S rRNA intergenic transcribed spacer (ITS) region [26] (Table 2). Polymerase chain reaction was performed in 50 μl reaction volumes containing extracted template DNA, 10 μl of 5× Green GoTaq reaction buffer, 200 μM of each dNTP, 0.5 μM of each forward and reverse primer and 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI), in an Eppendorf Mastercycler (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY). The conditions for the gltA reactions were 2 min at 95°C, 35 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 50°C for 45 s, 72°C for 30 s, and a 7 min extension at 72°C. The ITS PCR conditions were 2 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 66°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min and a 7 min extension at 72°C. PCR products were visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel, and amplicons matching the target length were sequenced on a 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) to confirm their identity.

Tissue preparation for histopathological analysis

Tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI), subjected to standard processing, and embedded in paraffin. Sections of 5 μm were then prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for evaluation by light microscopy (Colorado Histo-Prep, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA). Age-matched, saline inoculated control mouse tissues were treated in similar fashion, and all sections were read without prior knowledge of the experimental groups.

Results

Inoculation of mice--examinations and gross observations

Within the first week following inoculation, all mice exhibited thickened, tough skin at the inoculation site in the scruff of the neck. This resolved in surviving mice by week 4. The scruff skin of saline inoculated control mice remained thin and supple throughout the course of the study.

All mice inoculated with B. tamiae developed subcutaneous masses on the lateral thorax from 2 weeks post-inoculation, and some masses were still present at the conclusion of the study (6 weeks). Inguinal lymph node enlargement was detectable by palpation in mice during this same time period. Between weeks 2 and 3, mice inoculated with isolates Th307 and Th339 developed superficial ulcerations above several of the thoracic subcutaneous masses. Mice inoculated with Th239 did not develop skin ulcerations of subcutaneous masses. The subcutaneous masses did not appear painful upon palpation at any time during the course of the study, i.e. mice did not display aversion to handling or palpation of masses at any time.

PCR detection of BartonellaDNA in tissues

Sequencing of PCR positive samples confirmed the presence of B. tamiae DNA in five mouse tissues (Table 3). B. tamiae DNA was detected 3 weeks post-inoculation in a subcutaneous mass and the liver of a mouse inoculated with Th339. DNA was also detected in the subcutaneous mass and lymph node of another mouse inoculated with Th339, 5 weeks post-inoculation. One mouse inoculated with Th307 was also found to have a B. tamiae DNA positive subcutaneous mass at week 3. No blood or tissue samples collected from mice inoculated with Th239 contained detectable B. tamiae DNA. Samples collected from the two saline inoculated control mice were not found to contain B. tamiae DNA by PCR analysis. Nucleotide sequence analysis indicated that the detected DNA was identical to the inoculated strains.

Histopathological observations

As summarized in Table 4, differences in pathogenicity among B. tamiae isolates were noted. Th307 appeared less pathogenic than Th239 or Th339 when inoculated into mice, as only a deep dermatitis was seen at week 3, and a multifocal granulomatous nephritis was noted at weeks 5 and 6 after inoculation. This contrasts with Th239 and Th339 where granulomatous lesions were noted within the heart, kidney, liver and spleen of inoculated mice (Table 4). Lesions in the dermis occurred early after inoculation with Th307 and Th339 (3 weeks), while lesions of internal organs induced by all three isolates were noted at week 4 and persisted through week 6 post-inoculation (the duration of the study).

At week 5, in the hearts of mice inoculated with Th239 and Th339, a diffuse myocarditis was noted. Inflammation consisted primarily of mononuclear cells (lymphocytes and plasma cells) admixed with neutrophils occurring between myocytes (Figure 1-A). As noted in Figure 1-B, pyknotic nuclei and necrosis of adjacent myocardial muscle cells was seen (Figure 1-B, arrow). Also, granulomas were seen within both the right and left atria, with necrosis of adjacent muscle cells (Figure 1-C).

Photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin stained heart sections of mice sampled during the study. Mononuclear cell infiltration of the ventricle (A, 10×; B, 40×) and atrium (C, 10×) of a Swiss Webster mouse 5 weeks post-inoculation with B. tamiae Th339. The white arrow indicates a myocyte with a pyknotic nucleus. (D) Ventricle of a Swiss Webster mouse inoculated with saline (10×).

In the liver, multifocal pyogranulomatous infiltrates were noted adjacent to central veins (Figure 2-A) in association with hepatocellular necrosis (Figure 2-B, arrow). In the kidneys a perivascular granulomatous nephritis with associated degeneration and necrosis of glomeruli was noted in both kidneys (Figure 3-A, black arrows). These granulomas appeared to be associated with degeneration of proximal tubules (Figure 3-A, white arrow), and inflammation in kidneys was seen primarily within the renal cortex. Lesions within internal organs appeared to be perivascular, and, as noted in Figure 3-B, a necrotizing vasculitis occurred in prominent arteries of the cortex of the lymph nodes draining associated skin lesions. In the spleen, a necrotizing splenitis was seen, with a mixed inflammatory response occurring within both the red and white pulp (not shown). In the case of a mouse inoculated with Th339, a diffuse and prominent hemosiderosis was also seen within the white pulp of the spleen.

Photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin stained liver sections from mice sampled during the study. Granulomatous cell infiltration in liver tissue (A, 10×; B, 40×) of a Swiss Webster mouse inoculated with B. tamiae Th239. The black arrow indicates a necrotic hepatocyte. (C) Section of liver from a Swiss Webster mouse inoculated with saline (20×).

Photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin stained kidney and lymph node sections from mice sampled during the study. Granulomatous cell infiltration in the kidney (A, 10×) of a Swiss Webster mouse inoculated with B. tamiae Th239. Black arrows indicate degenerative glomeruli; the white arrow indicates a degenerating proximal tubule. (B) Necrotizing vasculitis in an axillary lymph node recovered from a Swiss Webster mouse 6 weeks after inoculation with B. tamiae Th339 (40×).

In the skin, caudal and lateral to the B. tamiae inoculation site, a necrotizing, ulcerative dermatitis developed dorsal to the subcutaneous masses early (3 weeks after inoculation of the mice with Th339, Table 4). The dermatitis persisted throughout the six week study period in some mice. Grossly, the lesions induced by Th339 appeared as ulcerative nodules, while microscopically, a severe, mixed inflammatory response was noted within the deeper layers of the dermis and subcutaneous tissues with associated necrosis of adjacent structures, such as hair follicles and sebaceous glands. Inflammatory infiltrates appeared similar to what was noted in the heart, liver, and kidney lesions, consisting of neutrophils admixed with mononuclear cells, predominantly plasma cells and mature lymphocytes. None of the above described lesions were seen in saline-inoculated control mice.

Discussion

Inoculation of Swiss Webster mice aged 15-18 months with human isolates of B. tamiae induced disease processes consistent with clinical manifestations of disease observed in human patients [23]. Since mice experience age-related changes in immune function, which include alterations in T-cell responsiveness to antigens, this may have affected the outcome of our study [27, 28]. Future studies will include younger mice to evaluate for age differences in response to this pathogen.

Two of the evaluated isolates of B. tamiae, Th239 and Th339, appear more pathogenic than the third, Th307 (Table 4). This corresponds to the presentation of the human patients from whom these isolates were obtained [23]. Patients 239 and 339 had rashes, and were febrile for 6 and 1 day(s) respectively, whereas Patient 307 was afebrile, and presented with pterygium in both eyes: all three patients had anemia [23]. In addition, the report of liver function abnormalities found in the human patients [23] would be consistent with hepatocellular disease, also seen in mice in the present study (Table 4, Figure 2). Immunopathological changes in the liver are not uncommon following human and cat infection with B. henselae [29–32], or Bartonella clarridgeiae [31]. B. tamiae DNA was found in the liver of one mouse infected with Th339 three weeks after inoculation (Table 3). Although B.tamiae DNA was detected, the question remains whether persistent bacteria in tissues or an inflammatory response directed toward bacterial antigen(s) was responsible for the perivascular granulomas and hepatocellular necrosis seen at week 6 in our mice (Table 4). In fact, it remains unclear whether any of the lesions observed were induced, and persisted or progressed in the presence or absence of viable bacteria.

It is unknown whether the three human patients infected with B. tamiae had cardiac disease [23]. No clinical tests were reported to have been conducted to evaluate for cardiac function abnormalities [23]. In the present study, B. tamiae Th239 and Th339 produced myocarditis in mice, with a diffuse inflammatory response associated with myocardial cell necrosis within both ventricles (Figure 1). Moreover, granulomatous lesions were observed in both atria 5 weeks post-inoculation (Table 4, Figure 1). Myocarditis in humans and animals has been associated with several Bartonella species [31, 33–36]. Advances in diagnostic techniques have implicated B. quintana, B. henselae, and B. elizabethae in the majority of Bartonella-associated human myocarditis cases [37–39], while B. vinsonii subspp. berkhoffii seems to be the main cause of Bartonella induced myocarditis in dogs [33]. Histopathological findings in experimentally infected cats, and in naturally acquired human and dog cases of Bartonella myocarditis, are consistent with our observations in mice [31, 33, 40]. Shared characteristics of infection of heart tissue among these cases and our murine model include mixed inflammatory infiltrates [31, 33, 40], and myocyte necrosis [33, 40], with random inflammatory foci found throughout heart tissue (Figure 1).

To our knowledge this is the first report of myocarditis associated with the inoculation of B. tamiae. Though the mice in our study had a diffuse myocarditis, and no endocarditis was found in hearts sampled during our study (n = 4; hearts sampled from experimentally inoculated mice at weeks 4 and 5), it is intriguing to note that a high rate of culture negative infective endocarditis exists in Khon Kaen, Thailand [41]. This is the same area where the patients reside from whom B. tamiae was isolated [23]. In the human endocarditis cases, the causative agent(s) is unknown, but the possible involvement of Bartonella bacteria has not been stringently evaluated [41]. In Thai patients with infective endocarditis, the mean period of time from symptoms to diagnosis was 5.7 weeks [41], and our present study only lasted to 6 weeks, with mouse hearts sampled at weeks 4 and 5 only. Further evaluation of our mouse model for B. tamiae induced disease may reveal more extensive cardiac involvement, especially in the context of a longer term study. Additional studies are also needed to determine the immunopathogenesis of these lesions in this murine model.

Lymphadenitis, and lymphadenitis with vasculitis, was seen in mice inoculated with B. tamiae Th239 and Th339, and sacrificed at weeks 5 and 6, and week 6 respectively (Table 4). This finding is consistent with presentations of Bartonella infections in human patients, as lymphadenitis is a common manifestation in immunocompetent humans infected with B. henselae [42]. It has also been observed in humans during infection with B. quintana [43] and B. alsatica [44], and in dogs [45] and cats infected with B. henselae [46]. Though lymphadenitis was observed microscopically, no Bartonella DNA was detected in those three lymph node samples. A recently published B. henselae 'cat scratch disease' mouse model also reported persistent lymphadenopathy in mice, without detection of bacteria in the lymph nodes [22]. Conversely, in this study at week 5, B. tamiae DNA was detected by PCR in the lymph node of a mouse inoculated with Th339 (Table 3), but lymphadenitis was not observed in those tissues under microscopic examination. It appears that the presence of Bartonella DNA is not necessarily a predictor of pathological findings in the lymph nodes. Interestingly, of the four mice in our study inoculated with B. tamiae Th307, none displayed lymphadenitis, which supports our conclusion that this isolate differs in pathogenicity compared to strains Th239 and Th339.

Since little is known of the natural history of B. tamiae in Thailand, it is difficult to assess and quantitate human risk for acquiring infection with this suspected human pathogen [23]. Although a specific animal reservoir for the bacteria has not been identified, the epidemiological profile of the three patients shows some shared exposures congruent with Bartonella bacterial infections manifesting most often as zoonoses [23]. All three patients had a history of exposure to rats, and two had noted the appearance of rats in their homes in the weeks prior to the onset of their illness [23]. In recent years, a number of rodent associated Bartonella species have been isolated from patients exhibiting a wide variety of clinical illnesses [10]. These cases include B. elizabethae: endocarditis [10], B. grahamii: neuroretinitis [10], B. washoensis: myocarditis [10] and meningitis [4], and B. vinsonii subspp. arupensis: bacteremia with fever [10], and endocarditis [47]. To date, it remains unclear how these infections, as well as the human infections with B. tamiae [23], were acquired, whether by direct contact with an animal reservoir, or exposure to a hematophagous arthropod. Recently, B. tamiae DNA was detected by PCR assay in chigger mites and ticks collected from a variety of rodents in Thailand [48]. This finding suggests the involvement of chigger mites, ticks, and/or rodents in the transmission of B. tamiae to humans in Thailand.

Conclusions

In this study we explored the capacity of three B. tamiae isolates to induce a variety of disease manifestations in aged immunocompetent mice. Thus far, our observations are consistent with the classification of B. tamiae as a human pathogen, since inoculation with the bacteria produced necrotizing dermatitis, lymphadenitis, granulomatous nephritis and hepatitis, and myocarditis in mice. A variety of disease characteristics observed in our mouse model correlate with what has been observed in other animal models and in human bartonellosis [31, 33, 40]. This murine model lends itself to the study of the immunopathogenesis of bartonellosis caused by B. tamiae, as it reproduces clinical symptomatology found in human patients in Thailand [23]. In addition, future studies in mice will evaluate the role age may play in the manifestation of disease. Finally, though the natural host and transmission dynamics of B. tamiae are unknown at this time, several lines of evidence suggest that rodents and/or ectoparasites can present some risk to humans for acquiring infection with this bacteria.

References

Vayssier-Taussat M, Le Rhun D, Bonnet S, Cott V: Insights in Bartonella host specificity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009, 1166: 127-132. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04531.x.

Eremeeva ME, Gerns HL, Lydy SL, Goo JS, Ryan ET, Mathew SS, Ferraro MJ, Holden JM, Nicholson WL, Dasch GA, Koehler JE: Bacteremia, fever, and splenomegaly caused by a newly recognized bartonella species. N Engl J Med. 2007, 356 (23): 2381-2387. 10.1056/NEJMoa065987.

Vorou RM, Papavassiliou VG, Tsiodras S: Emerging zoonoses and vector-borne infections affecting humans in Europe. Epidemiology and Infection. 2007, 135 (8): 1231-1247. 10.1017/S0950268807008527.

Probert W, Louie JK, Tucker JR, Longoria R, Hogue R, Moler S, Graves M, Palmer HJ, Cassady J, Fritz CL: Meningitis Due to a Bartonella washoensis-like Human Pathogen. JCM. 2009, 00511-00509.

Jeanclaude D, Godmer P, Leveiller D, Pouedras P, Fournier PE, Raoult D, Rolain JM: Bartonella alsatica endocarditis in a French patient in close contact with rabbits. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009

Saisongkorh W, Rolain JM, Suputtamongkol Y, Raoult D: Emerging Bartonella in humans and animals in Asia and Australia. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand = Chotmaihet thangphaet. 2009, 92 (5): 707-731.

Breitschwerdt EB, Maggi RG, Duncan AW, Nicholson WL, Hegarty BC, Woods CW: Bartonella species in blood of immunocompetent persons with animal and arthropod contact. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007, 13 (6): 938-941.

Karem KL, Paddock CD, Regnery RL: Bartonella henselae, B. quintana, and B. bacilliformis: historical pathogens of emerging significance. Microbes and infection/Institut Pasteur. 2000, 2 (10): 1193-1205.

Jacomo V, Kelly PJ, Raoult D: Natural history of Bartonella infections (an exception to Koch's postulate). Clinical and diagnostic laboratory immunology. 2002, 9 (1): 8-18.

Dehio C: Molecular and cellular basis of bartonella pathogenesis. Annual review of microbiology. 2004, 58: 365-390. 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123700.

Karem KL: Immune aspects of Bartonella. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2000, 26 (3): 133-145. 10.1080/10408410008984173.

Regnath T, Mielke ME, Arvand M, Hahn H: Murine model of Bartonella henselae infection in the immunocompetent host. Infect Immun. 1998, 66 (11): 5534-5536.

Velho PS, Moraes AM, Cintra ML, Giglioli R, Goncalves SA, Shlessarenko N, Camargo ME: Bacillary Angiomatosis: Negative Results Using Normal Balb/c and Balb/c Nude Mice. Braz J Infect Dis. 1998, 2 (6): 300-303.

Boulouis HJ, Barrat F, Bermond D, Bernex F, Thibault D, Heller R, Fontaine JJ, Piemont Y, Chomel BB: Kinetics of Bartonella birtlesii infection in experimentally infected mice and pathogenic effect on reproductive functions. Infect Immun. 2001, 69 (9): 5313-5317. 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5313-5317.2001.

Infante B, Villar S, Palma S, Merello J, Valencia R, Torres L, Cok J, Ventosilla P, Manguina C, Guerra H, Henriquez C: BALB/c Mice resist infection with Bartonella bacilliformis. BMC research notes. 2008, 1: 103-10.1186/1756-0500-1-103.

Kabeya H, Tsunoda E, Maruyama S, Mikami T: Immune responses of immunocompetent and immunocompromised mice experimentally infected with Bartonella henselae. J Vet Med Sci. 2003, 65 (4): 479-484. 10.1292/jvms.65.479.

Koesling J, Aebischer T, Falch C, Schulein R, Dehio C: Cutting edge: antibody-mediated cessation of hemotropic infection by the intraerythrocytic mouse pathogen Bartonella grahamii. J Immunol. 2001, 167 (1): 11-14.

Arvand M, Mielke ME, Sterry K, Hahn H: Detection of specific cellular immune response to Bartonella henselae in a patient with cat scratch disease. Clinical infectious diseases. 1998, 27 (6): 1533-1534. 10.1086/517738.

Pappalardo BL, Brown TT, Tompkins M, Breitschwerdt EB: Immunopathology of Bartonella vinsonii (berkhoffii) in experimentally infected dogs. Veterinary immunology and immunopathology. 2001, 83 (3-4): 125-147. 10.1016/S0165-2427(01)00372-5.

Chomel BB, Henn JB, Kasten RW, Nieto NC, Foley J, Papageorgiou S, Allen C, Koehler JE: Dogs are more permissive than cats or guinea pigs to experimental infection with a human isolate of Bartonella rochalimae. Vet Res. 2009, 40 (4): 27-10.1051/vetres/2009010.

Werner J, Kasten R, Feng S, Sykes J, Hodzic E, Salemi M, Barthold S, Chomel B: Experimental infection of domestic cats with passaged genotype I Bartonella henselae. Veterinary microbiology. 2007, 122 (3-4): 290-297. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.01.018.

Kunz S, Oberle K, Sander A, Bogdan C, Schleicher U: Lymphadenopathy in a novel mouse model of Bartonella-induced cat scratch disease results from lymphocyte immigration and proliferation and is regulated by interferon-alpha/beta. Am J Pathol. 2008, 172 (4): 1005-1018. 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070591.

Kosoy M, Morway C, Sheff KW, Bai Y, Colborn J, Chalcraft L, Dowell SF, Peruski LF, Maloney SA, Baggett H, Sutthirattana S, Sidhirat A, Maruyama S, Kabeya H, Chomel BB, Kasten R, Popov V, Robinson J, Kruglov A, Petersen LR: Bartonella tamiae sp. nov., a newly recognized pathogen isolated from three human patients from Thailand. J Clin Microbiol. 2008, 46 (2): 772-775. 10.1128/JCM.02120-07.

Duncan A, Maggi R, Breitschwerdt E: A combined approach for the enhanced detection and isolation of Bartonella species in dog blood samples: pre-enrichment liquid culture followed by PCR and subculture onto agar plates. Journal of microbiological methods. 2007, 69 (2): 273-281. 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.01.010.

Norman AF, Regnery R, Jameson P, Greene C, Krause DC: Differentiation of Bartonella-like isolates at the species level by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism in the citrate synthase gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1995, 33 (7): 1797-1803.

Diniz PP, Maggi RG, Schwartz DS, Cadenas MB, Bradley JM, Hegarty B, Breitschwerdt EB: Canine bartonellosis: serological and molecular prevalence in Brazil and evidence of co-infection with Bartonella henselae and Bartonella vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii. Vet Res. 2007, 38 (5): 697-710. 10.1051/vetres:2007023.

Effros RB, Cai Z, Linton PJ: CD8 T cells and aging. Crit Rev Immunol. 2003, 23 (1-2): 45-64. 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v23.i12.30.

Miller RA, Berger SB, Burke DT, Galecki A, Garcia GG, Harper JM, Sadighi Akha AA: T cells in aging mice: genetic, developmental, and biochemical analyses. Immunological reviews. 2005, 205: 94-103. 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00254.x.

Breitschwerdt E: Feline bartonellosis and cat scratch disease. Veterinary immunology and immunopathology. 2008, 123 (1-2): 167-171. 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.01.025.

Massei F, Gori L, Macchia P, Maggiore G: The expanded spectrum of bartonellosis in children. Infectious disease clinics of North America. 2005, 19 (3): 691-711. 10.1016/j.idc.2005.06.001.

Kordick DL, Brown TT, Shin K, Breitschwerdt EB: Clinical and pathologic evaluation of chronic Bartonella henselae or Bartonella clarridgeiae infection in cats. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1999, 37 (5): 1536-1547.

Mastrandrea S, Simonetta Taras M, Capitta P, Tola S, Marras V, Strusi G, Masala G: Detection of Bartonella henselae - DNA in macronodular hepatic lesions of an immunocompetent woman. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009

Breitschwerdt EB, Atkins CE, Brown TT, Kordick DL, Snyder PS: Bartonella vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii and related members of the alpha subdivision of the Proteobacteria in dogs with cardiac arrhythmias, endocarditis, or myocarditis. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1999, 37 (11): 3618-3626.

Meininger GR, Nadasdy T, Hruban RH, Bollinger RC, Baughman KL, Hare JM: Chronic active myocarditis following acute Bartonella henselae infection (cat scratch disease). Am J Surg Pathol. 2001, 25 (9): 1211-1214. 10.1097/00000478-200109000-00015.

Wesslen L, Ehrenborg C, Holmberg M, McGill S, Hjelm E, Lindquist O, Henriksen E, Rolf C, Larsson E, Friman G: Subacute Bartonella infection in Swedish orienteers succumbing to sudden unexpected cardiac death or having malignant arrhythmias. Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases. 2001, 33 (6): 429-438. 10.1080/00365540152029891.

Kosoy M, Murray M, Gilmore RD, Bai Y, Gage KL: Bartonella strains from ground squirrels are identical to Bartonella washoensis isolated from a human patient. J Clin Microbiol. 2003, 41 (2): 645-650. 10.1128/JCM.41.2.645-650.2003.

McGill S, Hjelm E, Rajs J, Lindquist O, Friman G: Bartonella spp. antibodies in forensic samples from Swedish heroin addicts. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003, 990: 409-413. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07402.x.

Montcriol A, Benard F, Fenollar F, Ribeiri A, Bonnet M, Collart F, Guidon C: Fatal myocarditis-associated Bartonella quintana endocarditis: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2009, 3: 7325-10.4076/1752-1947-3-7325.

Pipili C, Katsogridakis K, Cholongitas E: Myocarditis due to Bartonella henselae. South Med J. 2008, 101 (11): 1186-

Meininger GR, Nadasdy T, Hruban RH, Bollinger RC, Baughman KL, Hare JM: Chronic active myocarditis following acute Bartonella henselae infection (cat scratch disease). The American journal of surgical pathology. 2001, 25 (9): 1211-1214. 10.1097/00000478-200109000-00015.

Pachirat O, Chetchotisakd P, Klungboonkrong V, Taweesangsuksakul P, Tantisirin C, Loapiboon M: Infective endocarditis: prevalence, characteristics and mortality in Khon Kaen, 1990-1999. Medical journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 2002, 85 (1): 1-10.

Resto-Ruiz S, Burgess A, Anderson BE: The role of the host immune response in pathogenesis of Bartonella henselae. DNA Cell Biol. 2003, 22 (6): 431-440. 10.1089/104454903767650694.

Maurin M, Raoult D: Bartonella (Rochalimaea) quintana infections. Clinical microbiology reviews. 1996, 9 (3): 273-292.

Angelakis E, Lepidi H, Canel A, Rispal P, Perraudeau F, Barre I, Rolain J-M, Raoult D: Human case of Bartonella alsatica lymphadenitis. Emerging infectious diseases. 2008, 14 (12): 1951-1953. 10.3201/eid1412.080757.

Morales S, Breitschwerdt E, Washabau R, Matise I, Maggi R, Duncan A: Detection of Bartonella henselae DNA in two dogs with pyogranulomatous lymphadenitis. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2007, 230 (5): 681-685. 10.2460/javma.230.5.681.

Kordick DL, Breitschwerdt EB: Relapsing bacteremia after blood transmission of Bartonella henselae to cats. Am J Vet Res. 1997, 58 (5): 492-497.

Fenollar F, Sire S, Wilhelm N, Raoult D: Bartonella vinsonii subsp. arupensis as an agent of blood culture-negative endocarditis in a human. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2005, 43 (2): 945-947. 10.1128/JCM.43.2.945-947.2005.

Kabeya H, Colborn J, Bai Y, Lerdthusnee K, Richardson J, Maruyama S, Kosoy M: Detection of Bartonella tamiae DNA in ectoparasites from rodents in Thailand and their sequence similarity with bacterial cultures from Thai patients. Vector borne and zoonotic diseases. 2010, 10 (5): 429-434. 10.1089/vbz.2009.0124.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/10/229/prepub

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This study was supported by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. TL was supported by an American Society for Microbiology/Coordinating Center for Infectious Diseases (ASM/CCID) Post-Doctoral Research Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MK and LC designed the study and performed the animal work. NZ assisted with the animal work, and made all the histopathological observations. TL carried out all testing of samples. LC drafted the manuscript, and it was reviewed by all other authors. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Colton, L., Zeidner, N., Lynch, T. et al. Human isolates of Bartonella tamiaeinduce pathology in experimentally inoculated immunocompetent mice. BMC Infect Dis 10, 229 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-10-229

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-10-229