Abstract

Background

Esophago-gastroduodenal anastomosis with rats mimics the development of human Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma by introducing mixed reflux of gastric and duodenal contents into the esophagus. However, use of this rat model for mechanistic and chemopreventive studies is limited due to lack of genetically modified rat strains. Therefore, a mouse model of esophageal adenocarcinoma is needed.

Methods

We performed reflux surgery on wild-type, p53 A135Vtransgenic, and INK4a/Arf +/- mice of A/J strain. Some mice were also treated with omeprazole (1,400 ppm in diet), iron (50 mg/kg/m, i.p.), or gastrectomy plus iron. Mouse esophagi were harvested at 20, 40 or 80 weeks after surgery for histopathological analysis.

Results

At week 20, we observed metaplasia in wild-type mice (5%, 1/20) and p53 A135Vmice (5.3%, 1/19). At week 40, metaplasia was found in wild-type mice (16.2%, 6/37), p53 A135Vmice (4.8%, 2/42), and wild-type mice also receiving gastrectomy and iron (6.7%, 1/15). Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma developed in INK4a/Arf +/- mice (7.1%, 1/14), and wild-type mice receiving gastrectomy and iron (21.4%, 3/14). Among 13 wild-type mice which were given iron from week 40 to 80, twelve (92.3%) developed squamous cell carcinoma at week 80. None of these mice developed esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Conclusion

Surgically induced gastroesophageal reflux produced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, but not esophageal adenocarcinoma, in mice. Dominant negative p53 mutation, heterozygous loss of INK4a/Arf, antacid treatment, iron supplementation, or gastrectomy failed to promote esophageal adenocarcinoma in these mice. Further studies are needed in order to develop a mouse model of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Esophageal adenocarcinoma is a rising malignancy in western world in the past 30 years, and now exceeds the incidence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [1]. It is generally recognized that gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and Barrett's esophagus are the major risk factors of esophageal adenocarcinoma [2]. Barrett's esophagus is a metaplastic lesion of esophageal squamous epithelium adapted to GERD. The risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett's esophagus is around 0.5% per year [3]. Even with extensive treatment, the 5-year survival rate of esophageal adenocarcinoma is still around 20% [4]. Therefore, it is important to better understand the underlying mechanisms of this disease.

Both genetic and environmental factors may contribute to the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Along with the progression of metaplasia, dysplasia and adenocarcinoma, p53 gene mutation and protein accumulation were frequently detected [5, 6]. It has been reported that p16 INK4awas frequently silenced by promoter hypermethylation in esophageal adenocarcinoma [7, 8]. p14 Arfwas also silenced by hypermethylation in some cases, yet to a less extent compared with p16 INK4a[7]. Among the environmental factors, long-term antacid therapy might promote esophageal adenocarcinoma by producing hypergastrinemia and promoting bile acid-induced mutagenesis in a neutral pH environment [9, 10]. Gastrectomy might contribute to the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma by inducing GERD [11]. Iron supplementation promoted carcinogenesis through oxidative stress as we have shown in the surgical models with rats [12].

Animal models are great tools for research on human diseases. An ideal animal model should recapitulate the disease in humans in etiology, pathogenesis, and molecular features. Currently, the most popular animal models of esophageal adenocarcinoma are surgical models with rats [12–15]. Several strains of rats, e.g., Sprague-Dawley, F344, Wistar, have been used to generate esophageal adenocarcinoma [14, 16, 17]. Various surgical procedures, such as esophagojejunostomy, esophagoduodenal anastomosis, and esophagogastroduodenal anastomosis, have been reported by us and others [12, 14, 15]. Both carcinogenesis and chemoprevention studies using rat models lead us to better understanding of esophageal adenocarcinoma and possible preventive strategies [18–23]. However, the use of rat models in mechanistic studies has been limited due to lack of genetically modified rat strains.

Mouse esophagus is very similar to rat esophagus in histology. Several mouse models of esophageal adenocarcinoma have been reported. Duncan et al. reported an E1A/E1B transgenic mouse model [24]. The advantage of this model was that mice developed adenocarcinoma at the squamocolumnar junction without surgery or carcinogen treatment. However, these mice can not be bred to keep a stable line. Fein et al. reported a p53 knockout mouse model with gastrectomy and esophagojejunostomy [25]. Out of twelve p53 knockout mice, 4 survived after 24 weeks of observation. Two of them had esophageal adenocarcinoma and another one had squamous cell carcinoma. In our study using p53 knockout mice, 28 of 32 operated mice died within 20 weeks after surgery and most within 8 weeks, due to spontaneous lymphomas or sarcomas. All of the 4 mice that survived 20 weeks after surgery developed visible tumors of esophageal adenocarcinoma (unpublished data). Therefore, due to the short life span of p53 knockout mice, application of this model is very limited. Another research group reported a mouse model of esophageal adenocarcinoma induced with esophagojejunostomy and a carcinogen, N-methyl-N-benzyl nitrosamine. Both wild-type and p27 knockout mice of Swiss-Webster strain developed esophageal adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, yet at a low frequency. With p27 knockout, the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma was as low as 23.3% [26, 27].

In this study, we aimed to develop a mouse model of esophageal adenocarcinoma with a well-established surgical procedure, which successfully induced esophageal adenocarcinoma in rats [12]. p53 A135Vmice carrying a dominant negative mutation of p53 gene, which have a longer life span and compromised p53 function [28], were used to enhance carcinogenesis. INK4a/Arf +/- mice were also included to test the potential effect of down-regulation of p16 INK4aand p14 Arfgenes on carcinogenesis. Besides, the potential roles of gastric acid and iron supplementation in carcinogenesis were examined by combining surgery with acid suppression and/or iron supplementation.

Methods

Animal breeding and maintenance

Wild-type A/J mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) as breeders. Two genetically modified mouse strains were obtained from Dr. Ming You's group at Washington University School of Medicine: [1] A/J mice carrying three copies of an Ala-135-Val p53 mutant transgene [28]; [2] A/J mice with heterozygous knockout of INK4a/Arf [29]. PCR genotyping was performed as described elsewhere [29].

We bred 151 male and 62 female wild-type mice, 36 male and 42 female p53 A135Vtransgenic mice, and 24 male and 5 female INK4a/Arf +/- mice for this study in our animal facility. These mice were housed 10 per cage in plastic cages with hardwood bedding and dust covers, in a HEPA-filtered, environmentally controlled room (24 ± 1°C, 12/12 h light/dark cycle). Animals were given lab chow before surgery. Solid food was withdrawn for one day after surgery. All mice were on AIN93M diet after surgery, except that Group E received AIN93M diet supplemented with 1,400 ppm omeprazole. All the diets were made by Research Diets, Inc. (New Brunswick, NJ) once every month and kept at 4°C until use.

Surgical procedures

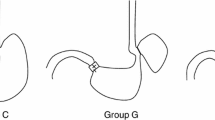

Six- to eight-week-old A/J mice were administered anesthetics pre-mixed in normal saline (80 mg/kg ketamine and 12 mg/kg xylazine, i.p.). Esophagogastroduodenal anastomosis was performed through an upper midline incision. Two 0.5 cm incisions were made on the esophagus and the duodenum on the anti-mesenteric border, and then were anastomosed together with accurate mucosal to mucosal opposition. Total gastrectomy was performed on some mice following the reflux procedure (Figure 1). These surgical procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Facilities Committee at Rutgers University (protocol no. 94-017).

After surgery, mice were divided into 6 groups: Group B (reflux surgery, 49 male and 52 female wild-type mice); Group C (reflux surgery, 36 male and 42 female p53 A135Vtransgenic mice); Group D (reflux surgery, 24 male and 5 female INK4a/Arf +/- mice); Group E (reflux surgery plus omeprazole and iron, 36 male wild-type mice); Group F (reflux surgery plus iron, 30 male wild-type mice); and Group G (reflux surgery plus gastrectomy and iron, 26 male wild-type mice). One group of wild-type mice (10 male and 10 female) were used as non-operated control (Group A) (Table 1).

Iron dextran (50 mg Fe/kg/month; Henry Schein, Melville, NY) was administered to mice of 4 groups through i.p. injection. Group F and Group G received iron supplementation starting from 2 weeks after surgery. Group E received iron supplementation from 20 to 40 weeks after surgery and Group B from 40 to 80 weeks after surgery.

All mice were euthanized by CO2. Esophagus was removed, opened longitudinally, and fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 h, and then transferred to 80% ethanol. The formalin-fixed esophagi were Swiss-rolled, processed and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections (5 μm) were mounted onto glass slides and used for histopathological analysis.

Histopathological analysis and immunostaining

H&E staining was performed on slides (No. 1 and 30) for diagnosis. Metaplasia was diagnosed when mucin-producing cells were observed in the squamous epithelium of mouse esophagus as confirmed by Alcian blue staining. Squamous dysplasia was diagnosed when squamous epithelial cells lost maturation and orientation with epithelial disorganization. Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma was diagnosed when squamous epithelial cells lost their normal orientation, had a high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, and were heterochromatic, and dysplastic cells broke basement membrane and invaded into lamina propria [30].

Tissue sections of wild-type mice (Group B) and p53 A135Vtransgenic mice (Group C) were stained for p53 protein in the esophagus. Paraffin sections were dewaxed in xylene, and rehydrated in a gradient of ethanol to distilled water. After quenching endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% hydrogen peroxide, tissue sections were incubated in normal horse serum to minimize non-specific binding. A polyclonal p53 antibody (Cat# NCL-p53-CM5p, Vision BioSystems Inc., Fremont, CA, 1:500) was applied at 4°C overnight. Tissue sections were then incubated with secondary biotin conjugated antibody at room temperature for 30 minutes. An avidin-biotin peroxidase complex (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was then applied, and the staining was visualized with diaminobenzidine. The sections were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin.

Statistic analysis

We compared the incidence of cancer with the Fisher's exact test.

Results

Most mice (85%, 255/300) survived the surgery. The rest died of anesthesia, bleeding or unknown reasons during the surgery. After surgery, mice lost about 3 to 5 g of body weight, and then started to gain weight to a less extent compared to the non-operated control mice (Figure 2). At the end of the experiment, mice with reflux had slightly lower body weight than the non-operated control. Fifty three mice were excluded from this study. Among them, 16 were sacrificed due to sickness and 37 died before the end of experiment (11 due to blockage of the gastrointestinal tract, 4 due to infection subsequent to iron injection, 22 due to unknown reasons). Autopsy of these 22 mice failed to find any noticeable abnormalities probably due to decay of the bodies.

Normal mouse esophagus is covered by stratified keratinized squamous epithelium consisting of several layers of squamous epithelial cells (Figure 3A). Reflux surgery induced hyperplasia of the squamous epithelium with infiltration of inflammatory cells in the epithelium and submucosa of all the mice (Figure 3B). At week 40 and 80, some mice developed squamous dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 3C, D, G and 3H).

Histopathology of mouse esophagus after reflux surgery. (A) In the non-operated control group, the basal layer of the epithelium was smooth and the nuclei were in a single line. (B) The epithelium responded to surgery-induced reflux with hyperplasia. Layers of the squamous epithelium increased and papillae were enlarged. (C) After long-term reflux, the epithelial cells started to lose their polarity with condensed nuclei and increased mitosis. (D) Later on, the squamous epithelium lost its normal architecture. Dysplastic cells penetrated the basal membrane and invade into the stroma. (E) At 20 weeks after the surgery, mucin-producing cells were observed in the parabasal layer of the squamous epithelium. (F) Alcian blue staining confirmed mucin secretion in these scattered mucinous cells. (G, H) At 80 weeks after surgery, squamous cell carcinoma was observed in the Swiss-rolled esophagus of a mouse in Group B. Panel H is magnification of part of Panel G.

At 20 weeks after surgery, one esophageal sample with metaplasia was found each in wild-type mice (Group B) and p53 A135Vtransgenic mice (Group C). Metaplasia was confirmed by Alcian blue staining as scattered mucinous cells in the middle of hyperplastic squamous cells (Figure 3E and 3F), as previously described in our rat model [31]. Mature goblet cells were not observed. The body weights of omeprazole treatment group (Group E) were significantly lower than the control group (data not shown).

At 40 weeks after surgery, we found 6, 2 and 1 esophageal samples with metaplasia in wild-type mice (Group B), p53 A135Vtransgenic mice (Group C), and reflux plus gastrectomy with iron supplementation (Group G). Squamous cell carcinoma was found in one INK4a/Arf +/- mouse (Group C) and 3 wild-type mice treated with reflux plus gastrectomy with iron supplementation (Group G). The incidence of squamous cell carcinoma in mice treated with reflux plus gastrectomy with iron supplementation (Group G) was significantly higher than that of mice treated with reflux alone (Group B) (p < 0.05).

Because we did not find any esophageal adenocarcinoma at week 40, we decided to give iron supplementation to the mice left in surgical control group (Group B). At 80 weeks after surgery, we found 12 mice with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in 13 wild-type mice. All squamous cell carcinoma were located at the distal part of the esophagus and invaded into the muscle layer (Figure 3G). Under higher magnification, neoplastic cells appeared to be originated from squamous epithelial cell, and were surrounded by muscle fibers (Figure 3H). The only one mouse without squamous cell carcinoma had mild squamous dysplasia. Metaplasia was not observed in these mice (Table 1).

Unexpectedly, none of the mice developed either esophageal adenocarcinoma or typical intestinal metaplasia as rats in our previous studies [31].

p53 expression in mouse esophagus

In order to examine the expression pattern of mutant p53 protein in the esophageal epithelium, we immunostained p53 using a polyclonal p53 antibody. In the esophageal epithelium of wild-type mice slight background staining was observed. In contrast, strong nuclear staining was observed in the basal cells of esophageal epithelium of the p53 A135Vtransgenic mice, suggesting accumulation of mutant p53 protein (Figure 4).

Discussion

This study was primarily aimed to develop a surgical model of esophageal adenocarcinoma in mice. Reflux surgery was performed on wild-type, p53 A135Vtransgenic and INK4a/Arf +/- mice of A/J background. In addition, omeprazole (1,400 ppm in diet), iron (50 mg/kg/m, i.p.), or gastrectomy plus iron, were given to some of these mice in order to promote disease progression. Unexpectedly, we only observed metaplasia as scattered mucinous cells, but not typical intestinal metaplasia, in a small percentage of mice. Moreover, squamous cell carcinoma, but not esophageal adenocarcinoma, was induced.

Long-term gastroesophageal reflux in combination with iron (Group B at week 80) produced a high incidence of squamous cell carcinoma (92.3%, 12/13) in this study. Although gastroesophageal reflux has been often associated with Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma, its association with squamous cell carcinoma has also been well documented in the literature. It is known that patients after total or partial gastrectomy had increased risk of developing esophageal and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma [32–35]. Reflux either directly induced or promoted esophageal squamous cell carcinoma following carcinogen treatment in rat models [36, 37]. In a previous study using the esophagoduodenal anastomosis procedure in rats, reflux increased the incidence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma induced by 2,6-dimethylnitrosomorpholine or methyl-n-amylnitrosamine by 40% [14]. Nevertheless, it was interesting why A/J mice were not susceptible to esophageal adenocarcinoma after reflux surgery. It is possible that mouse esophageal epithelium might respond to gastroesophageal reflux differently from rat esophageal epithelium, even though they are very similar in histology. Although the exact underlying mechanism remains puzzling, genetic factors may play a critical role.

Scattered mucinous cells were observed in mouse esophagi after surgery, suggesting that induction of Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma in mouse esophagus is still possible [31]. Our recent study on the rat model and human Barrett's esophagus have suggested squamous de-differentiation (i.e., loss of squamous transcription factors, p63, sox2) and columnar differentiation (i.e., gain of intestinal transcription factors, Cdx1, Cdx2, GATA4, HNF1α) were two essential aspects of intestinal metaplasia [38]. Since embryonic esophageal epithelium of p63 knockout mice and hypomorphic sox2 mice showed metaplastic changes of morphology and gene expression [39, 40], we speculate that p63 or sox2 knockout mice may be more susceptible to Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma after surgery. It is likely that proper combinations of genetic modifications and reflux surgery may be needed to induced Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma in mouse esophagus.

Rodent models of esophageal adenocarcinoma have its inherent limitations. Rodents have keratinized squamous epithelium without submucosal glands in the esophagus, whereas humans have non-keratinized squamous epithelium with submucosal glands. When histological and physiological resemblance to humans is considered, a model with pigs may offer many advantages over rodent models. As humans, pigs have non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium and submucosal glands in their esophagi [41]. Pigs may develop GERD and stress ulceration of the esophagus [42]. Pigs are also well suited for genetic modifications and surgery [43]. With endoscopy, pig esophagus may provide plenty of tissue samples for analysis. A pig model of Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma is currently under development in our laboratory.

Conclusion

In conclusion, reflux surgery induced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, but not esophageal adenocarcinoma, in wild-type, p53 A135Vtransgenic and INK4a/Arf +/- A/J mice. Further studies are needed in order to develop a mouse model of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Abbreviations

- GERD:

-

gastroesophageal reflux disease.

References

Holmes RS, Vaughan TL: Epidemiology and pathogenesis of esophageal cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2007, 17: 2-9. 10.1016/j.semradonc.2006.09.003.

Pera M: Recent changes in the epidemiology of esophageal cancer. Surg Oncol. 2001, 10: 81-90. 10.1016/S0960-7404(01)00025-1.

Pera M, Manterola C, Vidal O, Grande L: Epidemiology of esophageal adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2005, 92: 151-9. 10.1002/jso.20357.

Casson AG, van Lanschot JJ: Improving outcomes after esophagectomy: the impact of operative volume. J Surg Oncol. 2005, 92: 262-6. 10.1002/jso.20368.

McManus DT, Olaru A, Meltzer SJ: Biomarkers of esophageal adenocarcinoma and Barrett's esophagus. Cancer Res. 2004, 64: 1561-9. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2438.

Chung SM, Kao J, Hyjek E, Chen YT: p53 in esophageal adenocarcinoma: A critical reassessment of mutation frequency and identification of 72Arg as the dominant allele. Int J Oncol. 2007, 31: 1351-5.

Vieth M, Schneider-Stock R, Rohrich K, May A, Ell C, Markwarth A, Roessner A, Stolte M, Tannapfel A: INK4a-ARF alterations in Barrett's epithelium, intraepithelial neoplasia and Barrett's adenocarcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2004, 445: 135-41. 10.1007/s00428-004-1042-0.

Sarbia M, Geddert H, Klump B, Kiel S, Iskender E, Gabbert HE: Hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes (p16INK4A, p14ARF and APC) in adenocarcinomas of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Int J Cancer. 2004, 111: 224-8. 10.1002/ijc.20212.

Feagins LA, Zhang HY, Hormi-Carver K, Quinones MH, Thomas D, Zhang X, Terada LS, Spechler SJ, Ramirez RD, Souza RF: Acid has antiproliferative effects in nonneoplastic Barrett's epithelial cells. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007, 102: 10-20. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.01005.x.

Stamp DH: Bile acids aided by acid suppression therapy may be associated with the development of esophageal cancers in westernized societies. Med Hypotheses. 2006, 66: 154-7. 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.04.045.

Hsu CP, Chen CY, Hsieh YH, Hsia JY, Shai SE, Kao CH: Esophageal reflux after total or proximal gastrectomy in patients with adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997, 92: 1347-50.

Chen X, Yang G, Ding WY, Bondoc F, Curtis SK, Yang CS: An esophagogastroduodenal anastomosis model for esophageal adenocarcinogenesis in rats and enhancement by iron overload. Carcinogenesis. 1999, 20: 1801-8. 10.1093/carcin/20.9.1801.

Pera M, Cardesa A, Bombi JA, Ernst H, Pera C, Mohr U: Influence of esophagojejunostomy on the induction of adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus in Sprague-Dawley rats by subcutaneous injection of 2,6-dimethylnitrosomorpholine. Cancer Res. 1989, 49: 6803-8.

Attwood SE, Smyrk TC, DeMeester TR, Mirvish SS, Stein HJ, Hinder RA: Duodenoesophageal reflux and the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma in rats. Surgery. 1992, 111: 503-10.

Goldstein SR, Yang GY, Curtis SK, Reuhl KR, Liu BC, Mirvish SS, Newmark HL, Yang CS: Development of esophageal metaplasia and adenocarcinoma in a rat surgical model without the use of a carcinogen. Carcinogenesis. 1997, 18: 2265-70. 10.1093/carcin/18.11.2265.

Nishijima K, Miwa K, Miyashita T, Kinami S, Ninomiya I, Fushida S, Fujimura T, Hattori T: Impact of the biliary diversion procedure on carcinogenesis in Barrett's esophagus surgically induced by duodenoesophageal reflux in rats. Ann Surg. 2004, 240: 57-67. 10.1097/01.sla.0000130850.31178.8c.

Miwa K, Segawa M, Takano Y, Matsumoto H, Sahara H, Yagi M, Miyazaki I, Hattori T: Induction of oesophageal and forestomach carcinomas in rats by reflux of duodenal contents. Br J Cancer. 1994, 70: 185-9.

Goldstein SR, Yang GY, Chen X, Curtis SK, Yang CS: Studies of iron deposits, inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitrotyrosine in a rat model for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 1998, 19: 1445-9. 10.1093/carcin/19.8.1445.

Chen X, Yang CS: Esophageal adenocarcinoma: a review and perspectives on the mechanism of carcinogenesis and chemoprevention. Carcinogenesis. 2001, 22: 1119-29. 10.1093/carcin/22.8.1119.

Piazuelo E, Cebrian C, Escartin A, Jimenez P, Soteras F, Ortego J, Lanas A: Superoxide dismutase prevents development of adenocarcinoma in a rat model of Barrett's esophagus. World J Gastroenterol. 2005, 11: 7436-43.

Martin RC, Liu Q, Wo JM, Ray MB, Li Y: Chemoprevention of carcinogenic progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma by the manganese superoxide dismutase supplementation. Clin Cancer Res. 2007, 13: 5176-82. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1152.

Chen X, Li N, Wang S, Hong J, Fang M, Yousselfson J, Yang P, Newman RA, Lubet RA, Yang CS: Aberrant arachidonic acid metabolism in esophageal adenocarcinogenesis, and the effects of sulindac, nordihydroguaiaretic acid, and alpha-difluoromethylornithine on tumorigenesis in a rat surgical model. Carcinogenesis. 2002, 23: 2095-102. 10.1093/carcin/23.12.2095.

Chen X, Wang S, Wu N, Sood S, Wang P, Jin Z, Beer DG, Giordano TJ, Lin Y, Shih WC, Lubet RA, Yang CS: Overexpression of 5-lipoxygenase in rat and human esophageal adenocarcinoma and inhibitory effects of zileuton and celecoxib on carcinogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2004, 10: 6703-9. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0838.

Duncan MD, Tihan T, Donovan DM, Phung QH, Rowley DL, Harmon JW, Gearhart PJ, Duncan KL: Esophagogastric adenocarcinoma in an E1A/E1B transgenic model involves p53 disruption. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000, 4: 290-7. 10.1016/S1091-255X(00)80078-5.

Fein M, Peters JH, Baril N, McGarvey M, Chandrasoma P, Shibata D, Laird PW, Skinner KA: Loss of function of Trp53, but not Apc, leads to the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma in mice with jejunoesophageal reflux. J Surg Res. 1999, 83: 48-55. 10.1006/jsre.1998.5559.

Lechpammer M, Xu X, Ellis FH, Bhattacharaya N, Shapiro GI: Flavopiridol reduces malignant transformation of the esophageal mucosa in p27 knockout mice. Oncogene. 2005, 24: 1683-8. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208375.

Ellis FH, Xu X, Kulke MH, LoCicero J, Loda M: Malignant transformation of the esophageal mucosa is enhanced in p27 knockout mice. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001, 122: 809-14. 10.1067/mtc.2001.116471.

Harvey M, Vogel H, Morris D, Bradley A, Bernstein A, Donehower LA: A mutant p53 transgene accelerates tumour development in heterozygous but not nullizygous p53-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 1995, 9: 305-11. 10.1038/ng0395-305.

Wang Y, Zhang Z, Kastens E, Lubet RA, You M: Mice with alterations in both p53 and Ink4a/Arf display a striking increase in lung tumor multiplicity and progression: differential chemopreventive effect of budesonide in wild-type and mutant A/J mice. Cancer Res. 2003, 63: 4389-95.

Levin KJ, A H: Tumors of the Esophagus and Stomach. 1996, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington DC

Su Y, Chen X, Klein M, Fang M, Wang S, Yang CS, Goyal RK: Phenotype of columnar-lined esophagus in rats with esophagogastroduodenal anastomosis: similarity to human Barrett's esophagus. Lab Invest. 2004, 84: 753-65. 10.1038/labinvest.3700079.

Hashimoto N, Inayama M, Fujishima M, Ho H, Shinkai M, Hirai N, Kawanishi K, Imano M, Shigeoka H, Imamoto H, Shiozaki H: Esophageal cancer after distal gastrectomy. Dis Esophagus. 2006, 19: 346-9. 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00599.x.

Cammarota G, Galli J, Cianci R, De Corso E, Pasceri V, Palli D, Masala G, Buffon A, Gasbarrini A, Almadori G, Paludetti G, Gasbarrini G, Maurizi M: Association of laryngeal cancer with previous gastric resection. Ann Surg. 2004, 240: 817-24. 10.1097/01.sla.0000143244.76135.ca.

Mercante G, Bacciu A, Ferri T, Bacciu S: Gastroesophageal reflux as a possible co-promoting factor in the development of the squamous-cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, of the larynx and of the pharynx. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg. 2003, 57: 113-7.

Tachibana M, Abe S, Yoshimura H, Suzuki K, Matsuura H, Nagasue N, Nakamura T: Squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus after partial gastrectomy. Dysphagia. 1995, 10: 49-52. 10.1007/BF00261281.

Kuroiwa Y, Okamura T, Ishii Y, Umemura T, Tasaki M, Kanki K, Mitsumori K, Hirose M, Nishikawa A: Enhancement of esophageal carcinogenesis in acid reflux model rats treated with ascorbic acid and sodium nitrite in combination with or without initiation. Cancer Sci. 2008, 99: 7-13.

Chen KH, Mukaisho K, Ling ZQ, Shimomura A, Sugihara H, Hattori T: Association between duodenal contents reflux and squamous cell carcinoma–establishment of an esophageal cancer cell line derived from the metastatic tumor in a rat reflux model. Anticancer Res. 2007, 27: 175-81.

Chen X, Qin R, Liu B, Ma Y, Su Y, Yang CS, Glickman JN, Odze RD, Shaheen NJ: Multilayered epithelium in a rat model and human Barrett's esophagus: similar expression patterns of transcription factors and differentiation markers. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008, 8: 1-10.1186/1471-230X-8-1.

Yang A, Schweitzer R, Sun D, Kaghad M, Walker N, Bronson RT, Tabin C, Sharpe A, Caput D, Crum C, McKeon F: p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature. 1999, 398: 714-8. 10.1038/19539.

Que J, Okubo T, Goldenring JR, Nam KT, Kurotani R, Morrisey EE, Taranova O, Pevny LH, Hogan BL: Multiple dose-dependent roles for Sox2 in the patterning and differentiation of anterior foregut endoderm. Development. 2007, 134: 2521-31. 10.1242/dev.003855.

Long JD, Orlando RC: Esophageal submucosal glands: structure and function. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999, 94: 2818-24. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.1422_b.x.

Christie KN, Thomson C, Hopwood D: A comparison of membrane enzymes of human and pig oesophagus; the pig oesophagus is a good model for studies of the gullet in man. Histochem J. 1995, 27: 231-9.

Hofmann A, Kessler B, Ewerling S, Weppert M, Vogg B, Ludwig H, Stojkovic M, Boelhauve M, Brem G, Wolf E, Pfeifer A: Efficient transgenesis in farm animals by lentiviral vectors. EMBO Rep. 2003, 4: 1054-60. 10.1038/sj.embor.7400007.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-230X/9/59/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Ming You, Washington University School of Medicine, for providing the A/J mice carrying p53 A135Vmutation or heterozygous knockout of INK4a/Arf. This study was supported by NIH grants R01 CA75683, R03 CA125804, and U56 CA092077.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JH performed surgery on mice, contributed to study design, histopathology and data interpretation, and drafted the manuscript with XC. BL assisted surgery and animal care, and histopathology. CSY contributed to study design and data interpretation. XC performed surgery on mice, contributed to study design, histopathology and data interpretation, and drafted the manuscript with JH. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Hao, J., Liu, B., Yang, C.S. et al. Gastroesophageal reflux leads to esophageal cancer in a surgical model with mice. BMC Gastroenterol 9, 59 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-9-59

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-9-59