Abstract

Background

One of the rare presentations of superior vena cava syndrome is bleeding of "downhill" esophageal varices (DEV) and different approaches have been used to control it. This is a case report whose DEV was eradicated by band ligation for the first time.

Case presentation

We report a 42-year-old man who is a known case of Behcet's disease. The patient's first presentation was superior vena cava syndrome due to thrombosis followed by bipolar ulcers and arthralgia. He received warfarin, prednisolone and azathioprine. The clinical course of the patient was complicated by one episode of hematemesis without abdominal pain when the patient's PT was in therapeutic range. After resuscitation and correction of PT with fresh frozen plasma transfusion, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was done. Prominent varices were seen in the upper third of the esophagus, tapering to the middle part without acute bleeding. Stomach and duodenum were normal. Color ultrasonography evaluation of the portal, hepatic and splenic veins was negative for thrombosis. Band ligation was done and the patient's bleeding did not recur.

Conclusion

Band ligation is a safe and effective method for controlling DEV bleeding in patients with uncorrectable underlying disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

"Downhill" esophageal varices (DEV) which develop in the upper third of the esophagus are less common than distal esophageal varices, i.e. the uphill type, which is usually produced by portal hypertension [1, 2]. DEV serve as collateral branches directing blood flow "downwards", either to bypass superior vena cava [SVC] obstruction via azygus vein, or to drain the superior systemic system to the portal vein when both the SVC and the azygus vein are obstructed [3]. Predominant factors involved in the determination of the downward extension of varices along the esophagus are the level of SVC obstruction and its duration [2, 4]. The more distal the obstruction of SVC and the slower the process of occlusion, the higher the possibility of DEV developing. With obstruction of the SVC and the azygus vein, venous blood flow from the cranium and upper extremities may flow through the inferior thyroid veins and mediastinal collaterals into esophageal veins and then into the coronary vein to the portal vein, hepatic vein and inferior vena cava to the heart, resulting in "downhill" varices [4, 5].

"Downhill" varices are mostly due to SVC syndrome secondary to mass effects including lung cancers [6–9], intrathoracic goiter [3, 10–12], mediastinal lymphoma [13], thyroid carcinoma [14, 15], thymoma [2, 16], mediastinal lymphadenopathy secondary to different head, and neck cancers such as carcinoma of the tongue [7]. Less frequent etiologies of DEV are Behcet's disease [17–20], systemic venulitis [21], thyroid disease or a history of thyroid surgery [10, 22], fibrosing mediastinitis [23], as a complication of upper extremity hemodialysis access [24], Castleman's disease (angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia) [1], muscular constriction of abnormal extensions of posterior hypopharyngeal veins, and venous obstruction as a rare late complication after correction of congenital heart defect [25], and interestingly, one report of liver cirrhosis [26]. Intramural esophageal hematoma (pseudo-DEV) should also be considered in the differential diagnosis [27].

Case Presentation

A 42-year-old man presented with sudden-onset hematemesis. Everything had started a year before, when he had developed shortness of breath along with a plethoric face. The patient was admitted to the Surgery Department and was diagnosed with SVC thrombosis by means of Doppler ultrasonography and spiral computed tomography (CT) scan of chest (figure 1). The subject underwent thoracotomy out of suspicion of mediastinal mass effect on SVC, detected on thoracic spiral CT scan to be a thymoma or a thymus-associated mass. In the operation, no discrete mass was found and the thymus gland was removed and sent for pathologic review. No pathologic finding was detected and the gland had normal histological appearance. The patient received anticoagulant therapy in the form of warfarin 5 mg/day for 9 months. Then, he developed arthralgia of knee, wrist, elbow and ankles but no documented arthritis. He was examined by a rheumatologist when he was discovered to have positive pathergy test (positive cutaneous hypersensitivity reaction to intradermal injection of saline) and an oral aphthous ulcer. The history of genital ulcer was also positive in the patient. The diagnosis of Behcet's disease was made and the patient was treated with prednisolone tablets, 15 mg/day, and azathioprine, 100 mg/day; warfarin was also continued. A follow-up CT scan showed prominent mediastinal collateral veins close to the esophagus (figure 2).

Two weeks later, the patient presented with sudden onset of hematemesis and was admitted to the Emergency Room. He did not mention any past history of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Review of systems was not contributory. The patient was conscious and agitated. His blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg, but he had orthostatic hypotension with resting heart rate of 104/min. The patient had plethoric face and engorgement of jugular vein. Conjunctivae were pale and sclerae were anicteric. Pemberton's sign was detected; i.e. within 30 seconds after raised both arms simultaneously (Pemberton's maneuver), marked facial plethora (Pemberton's sign) developed, indicating compression of the jugular vein. Abdomen was soft with no tenderness, organomegaly or shifting dullness. Nervous system, musculoskeletal system, joints and the peripheral vascular system were all normal. A nasogastric tube was inserted and coffee ground secretions were revealed. Lab data were as follows: WBC: 6400, Hb: 6.5 g/dl, MCV: 97, MCH: 32, Platelet: 241,000, PTT: 40 seconds, PT: 18 seconds, INR: 2.1, albumin: 4 g/dl, ALT: 23, Alkaline Phosphatase: 170 (normal), BUN: 18 mg/dl, Cr: 0.6 mg/dl, Na: 138 meq/dl, K: 4.2 meq/dl.

The patient received 6 fresh frozen plasma (FFP) units and 4 units of packed red cells and his INR was rechecked after FFP infusion, when it was corrected to 1.3.

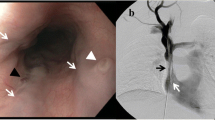

Because of underlying vasculitis, the diagnosis of portal vein thrombosis and bleeding due to esophageal varices was considered. The patient received intravenous infusion of octreotide and intravenous infusion of ranitidine. The bleeding stopped and the patient was closely monitored in the Emergency Room. Warfarin and azathioprine were discontinued and intravenous hydrocortisone was started instead of oral prednisolone. The patient underwent upper endoscopy on the day of admission and esophageal varices were found. Gastric and duodenal mucosae were intact. Abdominal ultrasound was normal and no evidence of ascites, splenomegaly and chronic liver disease was found. To rule out portal vein thrombosis as the cause of esophageal varices, Doppler ultrasonography was performed and mesenteric, splenic, portal and hepatic veins were evaluated; no discrete thrombosis was detected. He was not able to perform MR angiography because of his economic status. The patient underwent re-endoscopy by a second endoscopist and red color sign or stigma of recent bleeding plus esophageal varices were found in the upper half of esophagus tapering to the middle part of esophagus (figure 3); the diagnosis of "downhill" esophageal varices was made and band ligation was performed successfully (figure 4). He received oral cyclophosphamide 100 mg/day upon recommendation of rheumatologist. Omeprazole was administered too.

The patient was discharged from hospital the following day without any complication. Two weeks later, the third endoscopy along with the second band ligation was performed. He was discharged without any further episodes of bleeding. After 1 and 6 months, the patient underwent the 4th and 5th endoscopies and "downhill" esophageal varices were found to have been eradicated. Warfarin was initiated for patient and he has been well with no bleeding during the past 16 months. We are going to do surveillance endoscopies in this patient every 1–2 years.

Discussion

Mediastinal tumor-induced DEV is seen sporadically, but one due to SVC obstruction secondary to Behcet's disease is very rare [20]. Interestingly, SVC syndrome could be the initial symptom in Behcet's disease [18] as in the presented case. The most frequent signs and symptoms were face or neck swelling (82%), upper extremity swelling (68%), dyspnea (66%), cough (50%), and dilated chest vein collaterals (38%). Dyspnea at rest, cough, and chest pain were more frequent in patients with malignancy [28]. One of the unseen manifestations of SVC syndrome often discovered accidentally is DEV and upper gastrointestinal bleeding could be its first presentation. After reviewing approximately 130 cases of DEV, Maton et al. found only 9% to have gastrointestinal hemorrhage, much lower than that in uphill varices [21]. But the bleeding could be life-threatening [21, 24].

In some cases, varices disappear following treatment of the underlying etiology (table 1), e.g. treatment of systemic vasculitis by steroids and dapsone [21], chemoradiotherapy or resection of the tumor [1, 13] or thyroidectomy in the presence of intrathoracic goiter [10, 11, 15]. On the other hand, since fatal pulmonary embolism may happen after endoscopic sclerotherapy of "downhill" esophageal varices, cyanoacrylate injection into a varice above the lower third of the esophagus is a high-risk procedure [29]. In the presented case, eradication of upper esophageal varices didn't lead to any other visible variceal development either in hypopharynx or lower esophagus or stomach up to six months after band ligation. Then, band ligation seems to be a safe method of controlling DEV bleeding in patients with uncorrectable underlying disorders. But, further evaluations with large number of patients are warranted before drawing definite conclusions.

References

Serin E, Ozer B, Gumurdulu Y, Yildirim T, Barutcu O, Boyacioglu S: A case of Castleman's disease with "downhill" varices in the absence of superior vena cava obstruction. Endoscopy. 2002, 34 (2): 160-162. 10.1055/s-2002-19840.

Papazian A, Capron JP, Remond A, Descombes P, Ringot PL, Desablens B, Lorriaux A: [Upper esophageal varices. Study of 6 cases and review of the literature]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1983, 7 (11): 903-910.

Fleig WE, Stange EF, Ditschuneit H: Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage from "downhill" esophageal varices. Dig Dis Sci. 1982, 27 (1): 23-27. 10.1007/BF01308117.

Rosenblatt ML, Rabinowitz M: "Downhill" esophageal varices (EV) secondary to fibrosing mediastinitis (FM). AJG. 2000, 95 (9): 2602-2603.

Pashankar D, Jamieson DH, Israel DM: "Downhill" esophageal varices. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999, 29 (3): 360-362. 10.1097/00005176-199909000-00024.

Tanaka H, Nakahara K, Goto K: [Two cases of "downhill" esophageal varices associated with superior vena cava syndrome due to lung cancer]. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1991, 29 (11): 1484-1488.

Kokubo M, Sasaki H, Sakai S, Murakawa S, Mori Y, Hirose H: ["Downhill" esophageal varices due to superior vena cava syndrome]. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1991, 29 (7): 854-857.

Woodring JH: Unusual radiographic manifestations of lung cancer. Radiol Clin North Am. 1990, 28 (3): 599-618.

Ishikawa M, Kozasa K, Munechika H, Hishida T, Miyasaka K, Kushima M, Iwai C, Kurosaka H: [A case of "downhill" esophageal varices with bronchogenic carcinoma]. Rinsho Hoshasen. 1987, 32 (10): 1153-1156.

Kelly TR, Mayors DJ, Boutsicaris PS: "Downhill" varices; a cause of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am Surg. 1982, 48 (1): 35-38.

Bedard EL, Deslauriers J: Bleeding "downhill" varices: a rare complication of intrathoracic goiter. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006, 81 (1): 358-360. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.08.020.

Anders HJ: Compression syndromes caused by substernal goitres. Postgrad Med J. 1998, 74 (872): 327-329.

Shirakusa T, Iwasaki A, Okazaki M: "Downhill" esophageal varices caused by benign giant lymphoma. Case report and review of "downhill" varices cases in Japan. Scand J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1988, 22 (2): 135-138.

van Beusekom HJ, Beex LV, Smals AG, Snel P, Kloppenborg PW: ["Downhill" esophageal varices in thyroid carcinoma]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1978, 122 (2): 38-41.

Johnson LS, Kinnear DG, Brown RA, Mulder DS: "Downhill" esophageal varices. A rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Arch Surg. 1978, 113 (12): 1463-1464.

Bos GM, Saleh A, Schouten HC, van Deursen CT: "Downhill" oesophagus varices: a clue to a serious disease. Neth J Med. 1992, 40 (1–2): 27-30.

Orikasa H, Ejiri Y, Suzuki S, Ishikawa H, Miyata M, Obara K, Nishimaki T, Kasukawa R: A case of Behcet's disease with occlusion of both caval veins and "downhill" esophageal varices. J Gastroenterol. 1994, 29 (4): 506-510. 10.1007/BF02361251.

Ichikawa M, Kobayashi H, Mukai M, Saitoh Y: [Superior vena cava syndrome as initial symptom of Vasculo-Behcet's disease – case report]. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1991, 29 (10): 1344-1348.

Tsuji S, Suzuki Y, Tomii M, Matsuoka Y, Kishimoto H, Irimajiri S: [Behcet's disease associated with multiple cerebral aneurysms and "downhill" esophageal varices caused by superior vena cava obstruction: a case report]. Ryumachi. 1990, 30 (5): 375-9. 381

Ishikawa R, Noguchi T, Matsumoto K: [A case of "downhill" esophageal varices – Behcet disease associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm and occlusions of the superior and inferior vena cava]. Nippon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1986, 87 (12): 1576-1582.

Maton PN, Allison DJ, Chadwick VS: "Downhill" esophageal varices and occlusion of superior and inferior vena cavas due to a systemic venulitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1985, 7 (4): 331-337. 10.1097/00004836-198508000-00013.

Smallridge RC: Metabolic and anatomic thyroid emergencies: a review. Crit Care Med. 1992, 20 (2): 276-291. 10.1097/00003246-199202000-00016.

Basaranoglu M, Ozdemir S, Celik AF, Senturk H, Akin P: A case of fibrosing mediastinitis with obstruction of superior vena cava and "downhill" esophageal varices: a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999, 28 (3): 268-270. 10.1097/00004836-199904000-00021.

Pop A, Cutler AF: Bleeding "downhill" esophageal varices: a complication of upper extremity hemodialysis access. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998, 47 (3): 299-303. 10.1016/S0016-5107(98)70331-1.

Miller LT, Lang P, Liberthson R, Grillo HC, Israel EJ: Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage as a late complication of congenital heart disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1996, 23: 452-456. 10.1097/00005176-199611000-00017.

Tincani E, Criscuolo C, Zenesini A, Bondi M: [An unusual site of bleeding from esophageal varices]. Recenti Prog Med. 1998, 89 (6): 301-303.

Mann J, Rydzak E: Pseudo-downhill Varices of the Esophagus. [Annual Supplement of Abstracts: Southern Medical Association's 98th Annual Scientific Assembly: Oral Presentation Abstracts: Abstracts of Scientific Papers: Section on Internal Medicine]. 2004

Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW: The superior vena cava syndrome: clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine (Baltimore). 2006, 85 (1): 37-42. 10.1097/01.md.0000198474.99876.f0.

Tsokos M, BASRRGSB: [Fatal pulmonary embolism after endoscopic embolization of "downhill" esophageal varix]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1998, 123 (22): 691-695.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-230X/6/43/prepub

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patient whose written consent was obtained for publication of his medical history within this case report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

HT was the gastroenterologist diagnosed DEV for the first time in this case and did the band ligation. MA was the internal medicine resident involved in patient management, who took a detailed history, recorded laboratory data and follow-up information. MH was the radiologist who also contributed to diagnosis through imaging evaluation. AE, HT, MA and MH all contributed by providing the figures. AE prepared the primary draft of manuscript and finally, all authors contributed in final manuscript preparation.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Tavakkoli, H., Asadi, M., Haghighi, M. et al. Therapeutic approach to "downhill" esophageal varices bleeding due to superior vena cava syndrome in Behcet's disease: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol 6, 43 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-6-43

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-6-43