Abstract

Background

Ascites is a major and common complication of liver cirrhosis. Large or refractory ascites frequently necessitates paracentesis. The aim of our study was to investigate the effects of paracentesis on hemodynamic and respiratory parameters in critically ill patients.

Methods

Observational study comparing hemodynamic and respiratory parameters before and after paracentesis in 50 critically ill patients with advanced hemodynamic monitoring. 28/50 (56%) required mechanical ventilation.

Descriptive statistics are presented as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data and median, range, and interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed data. Comparisons of hemodynamic and respiratory parameters before and after paracentesis were performed by Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Bivariate relations were assessed by Spearman’s correlation coefficient and univariate regression analyses.

Results

Median amount of ascites removed was 5.99 L (IQR, 3.33-7.68 L). There were no statistically significant changes in hemodynamic parameters except a decrease in mean arterial pressure (-7 mm Hg; p = 0.041) and in systemic vascular resistance index (-116 dyne·sec/cm5/m2; p = 0.016) when measured 2 hours after paracentesis. In all patients, oxygenation ratio (PaO2/FiO2; median, 220 mmHg; IQR, 161–329 mmHg) increased significantly when measured immediately (+58 mmHg; p = 0.001), 2 hours (+9 mmHg; p = 0.004), and 6 hours (+6 mmHg); p = 0.050) after paracentesis. In mechanically ventilated patients, lung injury score (cumulative points without x-ray; median, 6; IQR, 4–7) significantly improved immediately (5; IQR, 4–6; p < 0.001), 2 hours (5; IQR, 4–7; p = 0.003), and 6 hours (6; IQR 4–6; p = 0.012) after paracentesis.

Conclusion

Paracentesis in critically ill patients is safe regarding circulatory function and is related to immediate and sustained improvement of respiratory function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ascites is a major and frequent complication of liver cirrhosis that is associated with high mortality [1–5]. The first line management of uncomplicated ascites includes dietary salt restriction and diuretics [6]. However, large or refractory ascites often necessitates paracentesis [7, 8].

Data on the safety and efficacy of large volume paracentesis (LVP) regarding hemodynamic function are contradictory. On the one hand, some studies suggest that LVP might deteriorate cardiocirculatory function or even induce circulatory failure [9, 10]. On the other hand, there are data showing that LVP with and without post interventional intravenous albumin substitution does not impair circulatory function and that it is more effective and less associated with complications than diuretic therapy [11–13]. Furthermore, ascites increases intraabdominal pressure and abdominal pressure causes impaired aeration of the lung in mechanically ventilated patients [14, 15]. A number of studies suggest improved respiratory function after paracentesis [16–21]. However, the vast majority of studies on the subject of paracentesis were not performed in critically ill patients with advanced hemodynamic monitoring or mechanical ventilation.

As critically ill patients are often in a hemodynamical unstable situation, LVP is likely to influence hemodynamics in these patients more than in non-ICU (intensive care unit) patients. Furthermore, estimation of volume status based on physical examination in critically ill patients is difficult [22]. This problem might be even more pronounced in patients with ascites. Therefore, advanced hemodynamic monitoring might help to accurately assess the fluid status and hemodynamic changes particularly in critically ill patients with ascites.

Therefore, the purpose of our study was to evaluate potential effects of paracentesis on hemodynamic parameters and respiratory function in ICU patients monitored using transpulmonary thermodilution (TPTD).

Methods

Study design, setting, patients, and data collection

We retrospectively analyzed a prospectively maintained database of patients undergoing paracentesis and monitored using TPTD (PiCCO®-device; Pulsion Medical Systems SE, Feldkirchen, Germany). The study was approved by the local ethics committee (Ethikkommission der Fakultät für Medizin der Technischen Universität München). Eighty-one paracenteses in 50 patients performed between January 2009 and July 2012 were eligible for the study. To avoid repeated measurements, only the first paracentesis of each patient was included in the analysis. All patients were equipped with hemodynamic monitoring irrespective of the study, and the decision to perform paracentesis was made by the treating ICU physician on clinical grounds independently from the study. Considering a possible impact of paracentesis on hemodynamic parameters as well as on the accuracy of their assessment by pulse contour analysis, re-calibration by TPTD after a major intervention is suggested by the manufacturer and part of clinical routine [23]. The same applies for the documentation of respiratory data before and after paracentesis. Twenty-eight of 50 (56%) patients were mechanically ventilated using pressure support ventilation or pressure control ventilation on the respirator Evita XL (Dräger Medical GmbH, Lübeck, Germany) or SERVO-i (Maquet, Rastatt, Germany). Data on ventilatory parameters (tidal volume (Vt), maximal inspiratory pressure (Pmax), positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), and fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2)) were recorded. Partial arterial oxygen pressure (PaO2) and partial arterial carbon dioxide pressure (PaCO2) were assessed using a fully automatic blood gas analysis system (RAPIDPOINT400, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics GmbH, Eschborn, Germany). Laboratory, hemodynamic, respiratory parameters, and patients’ characteristics were obtained after analysis of the patients’ medical charts. Cumulative points for lung injury score (LIS) without points for chest roentgenogram and oxygenation ratio (PaO2/FiO2) as well as inotropic score ((dopamine dose × 1) + (dobutamine × 1) + (epinephrine dose × 100) + (norepinephrine dose × 100) + (phenylephrine dose × 100)) and vasopressor dependency index (inotropic score/MAP) were calculated [24–27]. Hemodynamic parameters were available for all 50 patients immediately before and after paracentesis. Two hours after the end of paracentesis, data of 33/50 (66%) patients and 6 hours after paracentesis data of 34/50 (68%) were available. In mechanically ventilated patients, data for dynamic respiratory system compliance (Vt/Pmax-PEEP) and LIS were available immediately before paracentesis for all 28 patients, immediately after for 27/28 (96%). Data were additionally available 2 and 6 hours after the end of paracentesis in 21/28 (75%) and 18/28 (64%) patients, respectively [24].

Paracentesis and TPTD

Total paracentesis (removal of ascites without any volume restriction) was performed with a cannula (16–18 Gauge) connected to a bag without suction in a supine position as described before [28]. TPTD was performed as previously described immediately before and after paracentesis [29, 30]. Albumin substitution was at the discretion of the treating ICU physician [31].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Descriptive statistics are presented as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data and median, range, and interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed data. Comparisons of hemodynamic and respiratory parameters before and after paracentesis were performed by Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Bivariate relations were assessed by Spearman’s correlation coefficient and univariate regression analyses. Parameters with a corresponding p-value <0.1 were considered for multivariable linear regression analyses. Stepwise forward variable selection was performed using likelihood ratio tests (inclusion criteria p < 0.05). All statistical tests were 2-sided and performed in an explorative manner on a 5% significance level.

Results

Patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Paracentesis

Fifty paracenteses in 50 patients were analyzed. The median amount of ascites removed was 5.99 L (range, 0.49-17.06; IQR 3.33 - 7.68 L). Within the 6 hours follow up after paracentesis, a median amount of 100 mL (range, 0–500 mL; IQR, 0–200 mL) of 20% human albumin and a median volume of 350 mL (range, 0–830 mL; IQR, 203–565 mL) crystalloid infusions were administered.

Serum and ascites protein levels

The serum protein values within 72 hours before (median, 5.2 g/dL; range, 3.8-7.1 g/dL; IQR, 4.8-5.9 g/dL) and 72 hours after (median, 5.4 g/dL; range, 3.7-6.6 g/dL; IQR, 4.5-5.7 g/dL) paracentesis were available in 34/50 (68%) patients. The difference was statistically not significant (p = 0.068). Data for calculating the serum ascites protein gradient (SAPG) were available for 39/50 (78%) patients. Median SAPG was 4.1 (range, 2.5-6.5; IQR, 3.3-4.8).

Hemodynamics

Compared to baseline values, there were no statistically significant changes in hemodynamic parameters immediately, 2 hours and 6 hours after paracentesis except decrease of mean arterial pressure (MAP, -7 mm Hg; p = 0.041) and systemic vascular resistance index (SVRI, -116 dyne·sec/cm5/m2; p = 0.016) when measured 2 hours after paracentesis. Hemodynamic parameters before paracentesis as well as immediately, 2 hours, and 6 hours after the end of paracentesis are shown in Table 2.

Subgroup analysis including only mechanically ventilated patients did not reveal statistically significant or clinically relevant paracentesis-induced changes in hemodynamic parameters.

Vasopressor dependency index for all patients (median before paracentesis 0.0; IQR 0.0-374.1) did not change statistically significantly when measured immediately (median, 0.0; IQR, 0.0-343.4; p = 0.876), 2 hours (median, 0.0; IQR, 0.0-493.8; p = 0.650), and 6 hours (median, 0.0; IQR, 0.0-288.2; p = 0.711) after paracentesis. Subgroup analysis including only mechanically ventilated patients revealed similar results with a median vasopressor dependency index before paracentesis of 243.9 (IQR 0.0-735.3) and no statistically significant changes immediately (median, 253.2; IQR, 0.0-735.3; p = 0.679), 2 hours (median, 241.0; IQR, 0.0-762.3; p = 0.701), and 6 hours (median, 142.9; IQR, 0.0-709.7; p = 0.776) after paracentesis.

Subgroup analysis of patients undergoing paracentesis of more than 5 liters (n = 32) and more than 10 liters (n = 6) did not show any additional statistically significant changes in circulatory or TPTD derived parameters at any timepoint measured.

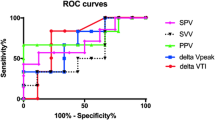

Respiratory function

In mechanically ventilated patients, a median baseline LIS of 6 points (IQR 4–7 points) and a median PaO2/FiO2 of 220 mmHg (IQR 161–329 mmHg) indicated severe respiratory dysfunction. In these patients, respiratory function markedly improved following paracentesis. Compared with the baseline values before paracentesis, LIS significantly improved immediately (-1 point; p < 0.001), 2 hours (-1 point; p = 0.003) and 6 hours (±0 points; p = 0.012) after paracentesis (Table 3). Similarly, PaO2/FiO2 significantly improved immediately (+54 mmHg; p < 0.001) and 2 hours (+24 mmHg; p = 0.001) after paracentesis. Furthermore, compliance significantly increased by 5.5 mL/cm H2O (p = 0.032) and 4.9 mL/cm H2O (p = 0.030) immediately and 2 hours after the end of paracentesis, respectively. Likewise to the subgroup of mechanically ventilated patients, PaO2/FiO2 statistically significantly increased also for all patients. Table 3 shows baseline respiratory parameters as well as values obtained immediately, 2 hours, and 6 hours after the end of paracentesis.

In univariate analysis including only mechanically ventilated patients, the amount of ascites removed (p = 0.013) and the parameters LIS before paracentesis (p = 0.004) and baseline PaO2/FiO2 (p = 0.012) were statistically significantly associated with paracentesis-induced changes in LIS when determined immediately after paracentesis. No statistically significant association was seen for simplified acute physiology score II (SAPS II) (p = 0.846), therapeutic intervention scoring system (TISS) (p = 0.950), dynamic respiratory system compliance before paracentesis (p = 0.350), and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score (p = 0.704). Subsequent multivariate linear regression analysis including the factors univariately associated confirmed LIS before paracentesis (p = 0.003) and amount of ascites removed (p = 0.009) as independent factors regarding improvement of LIS immediately after paracentesis compared with baseline values (Table 4).

Renal function

Despite a median negative 24-hour fluid balance on the day of intervention of -4.2 L (IQR, -6.0 L to -1.8 L), the median 24-hour urine output on the day after paracentesis (median, 800 mL; IQR, 250–1850 mL) was significantly higher (+200 mL; p = 0.015) when compared with the day before the intervention (median, 600 mL; IQR, 200–1300 mL).

Complications

Despite a marked general risk profile of the patients population in our study (mean SAPS II on the day of intervention 42 ± 13 points) and impaired blood coagulation tests (median INR 1.8 (IQR 1.4-2.6), median partial thromboplastin time 57 seconds (IQR, 45–75 seconds), median platelet count 58 × 109/L (IQR, 37–82 × 109/L); Table 1), no major bleeding or other intervention-related complications occurred.

Discussion

In this trial we analyzed the effects of paracentesis on hemodynamic parameters and respiratory function in critically ill patients.

According to the results of our study, no relevant impairment of circulatory function was observed whereas renal function in terms of urine output improved following removal of ascites. Furthermore, paracentesis is related to immediate and sustained improvement of respiratory function. The median oxygenation ratio of all patients increased, whereas PaCO2 remained stable after paracentesis.

Patients with tense ascites often display signs of circulatory dysfunction [32]. Portal hypertension leads to vasodilatation of splanchnic vessels, leading to decreased peripheral resistance, decreased effective central blood volume with consequent arterial hypotension and hyperdynamic circulation. These changes finally result in activation of vasoconstrictor systems, the renin-angiotensin-aldosteron system (RAAS) and the sympathetic nervous system, as well as increased levels of antidiuretic hormone, water retention and renal vasoconstriction, possibly ending in renal failure [33–35]. Infusion of albumin is recommended by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) for large volume paracentesis (> 5 Liter), because intravenously administered albumin increases the effective arterial blood volume and improves serum sodium concentrations in patients with cirrhosis and severe hyponatremia [36–40]. However, albumin does not interfere with the main mechanisms of ascites formation and therefore only prevents complications of paracentesis rather than prevents the recurrence of ascites [10].

Regarding hemodynamic parameters, paracentesis did neither result in an immediate nor in a delayed cardiocirculatory impairment. No statistically significant changes in arterial blood pressure, heart rate, or TPTD-derived parameters such as cardiac index (CI), global end diastolic volume index (GEDVI), and extra vascular lung water index (EVLWI) were observed after paracentesis. This is partly in contrast to some previous studies demonstrating a paracentesis-related deterioration of cardiac function and might be explained by the fact that volume resuscitation was guided using advanced hemodynamic monitoring in the patients included in our study during their ICU stay. This might have resulted in an optimized baseline (pre-paracentesis) hemodynamic and intravascular volume status in our patients indicated by normal baseline values for MAP, CI, and GEDVI assessed using advanced hemodynamic monitoring [9, 41–43]. Two hours after the intervention, MAP and SVRI were statistically significantly lower compared with the values before the intervention. However, 6 hours after the end of paracentesis, there was no statistically significant difference in MAP and SVRI compared with baseline values anymore. These paracentesis-related hemodynamic changes (decreased SVRI, unchanged GEDVI) two hours after the end of paracentesis are most likely due to a reduction of cardiac afterload as a consequence of a paracentesis-induced lower intraabdominal pressure [28]. In addition, the reduction of SVRI after paracentesis might be explained by the substitution of albumin following paracentesis. A significant reduction of SVRI after plasma-expansion with hyperoncotic albumin in cirrhotic patients with renal failure has been described before [34, 43]. However, Cabrera et al. observed no decrease of SVRI when removing ascites but maintaining the intraabdominal pressure at its original level in an experimental setting using a pneumatic girdle. Only after decrease of intraabdominal pressure, SVRI also decreased [44]. Since application rates of vasoactive drugs and the vasopressor dependency index were not significantly different before and after paracentesis, the decrease in SVRI in our study cannot be explained by a lower application rate of vasopressors following paracentesis. Based on the considerations mentioned before, the decrease in SVRI observed following removal of ascites is most likely caused by a paracentesis-related reduction of intraabdominal pressure [28, 45]. Unfortunately, documentation of intraabdominal pressure before and after paracentesis is not routinely performed in our ICU and was therefore not available for data analysis.

Given the fact, that all hemodynamic parameters were stable 6 hours after the end of paracentesis and that vasopressor dependency index did not change statistically significantly, LVP seems to be a safe procedure regarding circulatory function.

Regarding the positive impact of paracentesis on respiratory function, an improvement of oxygenation (while PaCO2 remained unchanged) was also observed in a previous study [18]. These positive effects regarding respiratory function are most likely due to improved respiratory mechanics as a consequence of a paracentesis-induced reduction of intraabdominal pressure [18, 21, 46]. The fact that paracentesis caused a significant improvement of dynamic respiratory system compliance in mechanically ventilated patients is also indicative for a decreased intraabdominal pressure following paracentesis. These findings are in accordance with the results from a recent study by Levesque and colleagues in 31 mechanically ventilated cirrhotic patients demonstrating a significant decrease in intraabdominal pressure, improvement of oxygenation, and an increase in end-expiratory lung volume after LVP [21]. The improvement of dynamic respiratory system compliance, LIS, and PaO2/FiO2 in mechanically ventilated patients demonstrates the possibility to reduce ventilator associated lung injury by removal of ascites in these patients.

The median urine output on the day after paracentesis was significantly higher compared with the day before the intervention. This indicates, as described before by our group and others, that paracentesis might help to improve renal function [43, 47]. The increase of urine output on the day after paracentesis despite a negative fluid balance on the day of paracentesis indicates that the reduction of intraabdominal pressure – besides possible humoral effects – is causative for the improvement of renal function [48].

Limitations of the study

There are several limitations of our study that need to be mentioned. In general, since we studied a limited number of paracenteses in a monocentric study, the results of our study need to be interpreted with caution. Especially the number of patients on mechanical ventilation is relatively low in our study. In addition, documentation of intraabdominal pressure before and after paracentesis is not routinely performed and therefore not available for data analysis. Finally, albumin substitution after paracentesis was at the discretion of the treating ICU physician and was not performed strictly adhering to international guidelines.

Conclusion

Our data indicate that paracentesis in critically ill patients is safe regarding hemodynamic function, renal function and intervention-related complications. Furthermore, paracentesis in critically ill and mechanically ventilated patients results in immediate and sustained improvement of respiratory function. Paracentesis might therefore help to limit ventilator associated lung injury.

References

Gines P, Quintero E, Arroyo V, Teres J, Bruguera M, Rimola A, Caballeria J, Rodes J, Rozman C: Compensated cirrhosis: natural history and prognostic factors. Hepatology. 1987, 7: 122-128. 10.1002/hep.1840070124.

Kim WR: The burden of hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology. 2002, 36: S30-S34.

Powell WJ, Klatskin G: Duration of survival in patients with Laennec’s cirrhosis. Influence of alcohol withdrawal, and possible effects of recent changes in general management of the disease. Am J Med. 1968, 44: 406-420. 10.1016/0002-9343(68)90111-3.

D’Amico G, Morabito A, Pagliaro L, Marubini E: Survival and prognostic indicators in compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 1986, 31: 468-475. 10.1007/BF01320309.

Llach J, Gines P, Arroyo V, Rimola A, Tito L, Badalamenti S, Jimenez W, Gaya J, Rivera F, Rodes J: Prognostic value of arterial pressure, endogenous vasoactive systems, and renal function in cirrhotic patients admitted to the hospital for the treatment of ascites. Gastroenterology. 1988, 94: 482-487.

Moore KP, Wong F, Gines P, Bernardi M, Ochs A, Salerno F, Angeli P, Porayko M, Moreau R, Garcia-Tsao G, Jimenez W, Planas R, Arroyo V: The management of ascites in cirrhosis: report on the consensus conference of the International Ascites Club. Hepatology. 2003, 38: 258-266.

Moore KP, Aithal GP: Guidelines on the management of ascites in cirrhosis. Gut. 2006, 55 (Suppl 6): vi1-vi12.

Runyon BA: Paracentesis of ascitic fluid. A safe procedure. Arch Intern Med. 1986, 146: 2259-2261. 10.1001/archinte.1986.00360230201029.

Ruiz-del-Arbol L, Monescillo A, Jimenez W, Garcia-Plaza A, Arroyo V, Rodes J: Paracentesis-induced circulatory dysfunction: mechanism and effect on hepatic hemodynamics in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1997, 113: 579-586. 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9247479.

Nasr G, Hassan A, Ahmed S, Serwah A: Predictors of large volume paracantesis induced circulatory dysfunction in patients with massive hepatic ascites. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2010, 1: 136-144. 10.4103/0975-3583.70914.

Peltekian KM, Wong F, Liu PP, Logan AG, Sherman M, Blendis LM: Cardiovascular, renal, and neurohumoral responses to single large-volume paracentesis in patients with cirrhosis and diuretic-resistant ascites. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997, 92: 394-399.

Quintero E, Gines P, Arroyo V, Rimola A, Bory F, Planas R, Viver J, Cabrera J, Rodes J: Paracentesis versus diuretics in the treatment of cirrhotics with tense ascites. Lancet. 1985, 1: 611-612.

Gines P, Arroyo V, Quintero E, Planas R, Bory F, Cabrera J, Rimola A, Viver J, Camps J, Jimenez W: Comparison of paracentesis and diuretics in the treatment of cirrhotics with tense ascites. Results of a randomized study. Gastroenterology. 1987, 93: 234-241.

Malbrain ML, Chiumello D, Pelosi P, Bihari D, Innes R, Ranieri VM, Del Turco M, Wilmer A, Brienza N, Malcangi V, Cohen J, Japiassu A, De Keulenaer BL, Daelemans R, Jacquet L, Laterre PF, Frank G, de Souza P, Cesana B, Gattinoni L: Incidence and prognosis of intraabdominal hypertension in a mixed population of critically ill patients: a multiple-center epidemiological study. Crit Care Med. 2005, 33: 315-322. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000153408.09806.1B.

Rouby JJ, Constantin JM, Roberto De AGC, Zhang M, Lu Q: Mechanical ventilation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2004, 101: 228-234. 10.1097/00000542-200407000-00033.

Chao Y, Wang SS, Lee SD, Shiao GM, Chang HI, Chang SC: Effect of large-volume paracentesis on pulmonary function in patients with cirrhosis and tense ascites. J Hepatol. 1994, 20: 101-105.

Angueira CE, Kadakia SC: Effects of large-volume paracentesis on pulmonary function in patients with tense cirrhotic ascites. Hepatology. 1994, 20: 825-828.

Byrd RP, Roy TM, Simons M: Improvement in oxygenation after large volume paracentesis. South Med J. 1996, 89: 689-692. 10.1097/00007611-199607000-00008.

Duranti R, Laffi G, Misuri G, Riccardi D, Gorini M, Foschi M, Iandelli I, Mazzanti R, Mancini M, Scano G, Gentilini P: Respiratory mechanics in patients with tense cirrhotic ascites. Eur Respir J. 1997, 10: 1622-1630. 10.1183/09031936.97.10071622.

Lalrothuama GD, Agrawal PN, Aggarwal AN, Dhiman RK, Behera D, Chawla Y: Pulmonary function changes after large volume paracentesis. Trop Gastroenterol. 2000, 21: 68-70.

Levesque E, Hoti E, Jiabin J, Dellamonica J, Ichai P, Saliba F, Azoulay D, Samuel D: Respiratory impact of paracentesis in cirrhotic patients with acute lung injury. J Crit Care. 2011, 26: 257-261. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.08.020.

Saugel B, Ringmaier S, Holzapfel K, Schuster T, Phillip V, Schmid RM, Huber W: Physical examination, central venous pressure, and chest radiography for the prediction of transpulmonary thermodilution-derived hemodynamic parameters in critically ill patients: a prospective trial. J Crit Care. 2011, 26: 402-410. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.11.001.

Gruenewald M, Renner J, Meybohm P, Hocker J, Scholz J, Bein B: Reliability of continuous cardiac output measurement during intra-abdominal hypertension relies on repeated calibrations: an experimental animal study. Crit Care. 2008, 12: R132-10.1186/cc7102.

Murray JF, Matthay MA, Luce JM, Flick MR: An expanded definition of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988, 138: 720-723. 10.1164/ajrccm/138.3.720.

El-Khatib MF, Jamaleddine GW: A new oxygenation index for reflecting intrapulmonary shunting in patients undergoing open-heart surgery. Chest. 2004, 125: 592-596. 10.1378/chest.125.2.592.

Cruz DN, Antonelli M, Fumagalli R, Foltran F, Brienza N, Donati A, Malcangi V, Petrini F, Volta G, Bobbio Pallavicini FM, Rottoli F, Giunta F, Ronco C: Early use of polymyxin B hemoperfusion in abdominal septic shock: the EUPHAS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009, 301: 2445-2452. 10.1001/jama.2009.856.

Zuppa AF, Nadkarni V, Davis L, Adamson PC, Helfaer MA, Elliott MR, Abrams J, Durbin D: The effect of a thyroid hormone infusion on vasopressor support in critically ill children with cessation of neurologic function. Crit Care Med. 2004, 32: 2318-2322.

Umgelter A, Reindl W, Wagner KS, Franzen M, Stock K, Schmid RM, Huber W: Effects of plasma expansion with albumin and paracentesis on haemodynamics and kidney function in critically ill cirrhotic patients with tense ascites and hepatorenal syndrome: a prospective uncontrolled trial. Crit Care. 2008, 12: R4-10.1186/cc6765.

Saugel B, Phillip V, Ernesti C, Messer M, Meidert AS, Schmid RM, Huber W: Impact of large-volume thoracentesis on transpulmonary thermodilution-derived extravascular lung water in medical intensive care unit patients. Care J Crit Care. 2013, 28: 196-201. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.05.002.

Sakka SG, Ruhl CC, Pfeiffer UJ, Beale R, McLuckie A, Reinhart K, Meier-Hellmann A: Assessment of cardiac preload and extravascular lung water by single transpulmonary thermodilution. Intensive Care Med. 2000, 26: 180-187. 10.1007/s001340050043.

Gines A, Fernandez-Esparrach G, Monescillo A, Vila C, Domenech E, Abecasis R, Angeli P, Ruiz-Del-Arbol L, Planas R, Sola R, Gines P, Terg R, Inglada L, Vaque P, Salerno F, Vargas V, Clemente G, Quer JC, Jimenez W, Arroyo V, Rodes J: Randomized trial comparing albumin, dextran 70, and polygeline in cirrhotic patients with ascites treated by paracentesis. Gastroenterology. 1996, 111: 1002-1010. 10.1016/S0016-5085(96)70068-9.

Schrier RW, Arroyo V, Bernardi M, Epstein M, Henriksen JH, Rodes J: Peripheral arterial vasodilation hypothesis: a proposal for the initiation of renal sodium and water retention in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1988, 8: 1151-1157. 10.1002/hep.1840080532.

Bernardi M, Caraceni P, Navickis RJ, Wilkes MM: Albumin infusion in patients undergoing large-volume paracentesis: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Hepatology. 2012, 55: 1172-1181. 10.1002/hep.24786.

Umgelter A, Wagner K, Reindl W, Nurtsch N, Huber W, Schmid RM: Haemodynamic effects of plasma-expansion with hyperoncotic albumin in cirrhotic patients with renal failure: a prospective interventional study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008, 8: 39-10.1186/1471-230X-8-39.

Salerno F, Guevara M, Bernardi M, Moreau R, Wong F, Angeli P, Garcia-Tsao G, Lee SS: Refractory ascites: pathogenesis, definition and therapy of a severe complication in patients with cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2010, 30: 937-947. 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02272.x.

Runyon BA: Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: an update. Hepatology. 2009, 49: 2087-2107. 10.1002/hep.22853.

Runyon BA: Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2012, 57: 1651-1653.

McCormick P, Mistry P, Kaye G, Burroughs A, McIntyre N: Intravenous albumin infusion is an effective therapy for hyponatraemia in cirrhotic patients with ascites. Gut. 1990, 31: 204-207. 10.1136/gut.31.2.204.

Jalan R, Mookerjee R, Cheshire L, Williams R, Davies N: Albumin infusion for severe hyponatremia in patients with refractory ascites: a randomized clinical trial. J Hepatol. 2007, 46: S95-

Sola E, Gines P: Renal and circulatory dysfunction in cirrhosis: current management and future perspectives. J Hepatol. 2010, 53: 1135-1145. 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.08.001.

Pozzi M, Osculati G, Boari G, Serboli P, Colombo P, Lambrughi C, De Ceglia S, Roffi L, Piperno A, Cusa EN: Time course of circulatory and humoral effects of rapid total paracentesis in cirrhotic patients with tense, refractory ascites. Gastroenterology. 1994, 106: 709-719.

Panos MZ, Moore K, Vlavianos P, Chambers JB, Anderson JV, Gimson AE, Slater JD, Rees LH, Westaby D, Williams R: Single, total paracentesis for tense ascites: sequential hemodynamic changes and right atrial size. Hepatology. 1990, 11: 662-667. 10.1002/hep.1840110420.

Umgelter A, Wagner KS, Reindl W, Luppa PB, Geisler F, Huber W, Schmid RM: Renal and circulatory effects of large volume plasma expansion in patients with hepatorenal syndrome type 1. Ann Hepatol. 2012, 11: 232-239.

Cabrera J, Falcon L, Gorriz E, Pardo MD, Granados R, Quinones A, Maynar M: Abdominal decompression plays a major role in early postparacentesis haemodynamic changes in cirrhotic patients with tense ascites. Gut. 2001, 48: 384-389. 10.1136/gut.48.3.384.

Guazzi M, Polese A, Magrini F, Fiorentini C, Olivari MT: Negative influences of ascites on the cardiac function of cirrhotic patients. Am J Med. 1975, 59: 165-170. 10.1016/0002-9343(75)90350-2.

Wauters J, Claus P, Brosens N, McLaughlin M, Hermans G, Malbrain M, Wilmer A: Relationship between abdominal pressure, pulmonary compliance, and cardiac preload in a porcine model. Crit Care Res Pract. 2012, 2012: 763181-

Wang HYAF, Yang XY, Yang XF, Ran XG: Clinical outcome after pressure reduction by peritoneal catheterization in 29 patients with malignant ascites-induced abdominal compartment syndrome. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2010, 13: 273-275.

Mohmand H, Goldfarb S: Renal dysfunction associated with intra-abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011, 22: 615-621. 10.1681/ASN.2010121222.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-230X/14/18/prepub

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Wolfgang Huber and Bernd Saugel collaborate with Pulsion Medical Systems SE (Feldkirchen, Germany) as members of the medical advisory board. All other authors have no conflict of interest. No financial support was obtained for the study.

Authors’ contributions

VP, BS and WH contributed to the conception and design of the study. VP, BS, CE, CS, PT and UM were responsible for acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. VP and WH drafted the manuscript. RMS and BS participated in study design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. AH participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Phillip, V., Saugel, B., Ernesti, C. et al. Effects of paracentesis on hemodynamic parameters and respiratory function in critically ill patients. BMC Gastroenterol 14, 18 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-14-18

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-14-18