Abstract

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common cause of disability and consultation with a GP. However, little is known about what currently happens when patients with OA consult their GP. This review aims to compare existing literature reporting patient experiences of consultations in which OA is discussed with GP attitudes and beliefs regarding OA, in order to identify any consultation events that may be targeted for intervention.

Methods

After a systematic literature search, a narrative review has been conducted of literature detailing patient experiences of consulting with OA in primary care and GP attitudes to, and beliefs about, OA. Emergent themes were identified from the extracted findings and GP and patient perspectives compared within each theme.

Results

Twenty two relevant papers were identified. Four themes emerged: diagnosis; explanations; management of the condition; and the doctor-patient relationship. Delay in diagnosis is frequently reported as well as avoidance of the term osteoarthritis in favour of ‘wear and tear’. Both patients and doctors report negative talk in the consultation, including that OA is to be expected, has an inevitable decline and there is little that can be done about it. Pain management appears to be a priority for patients, although a number of barriers to effective management have been identified. Communication within the doctor patient consultation also appears key, with patients reporting a lack of feeling their symptoms were legitimised.

Conclusions

The nature of negative talk and discussions around management within the consultation have emerged as areas for future research. The findings are limited by generic limitations of interview research; to further understanding of the OA consultation alternative methodology such as direct observation may be necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common arthritis, a common cause of disability and frequent cause of consultation with a GP. OA is predominantly managed in primary care, and comprehensive guidance suggests that much can be done to alleviate symptoms from osteoarthritis; a combination of therapeutic options including pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments are recommended [1–5].

However, evidence suggests that for many patients with OA, effective interventions appear not to have been adopted.

Firstly, various studies that have evaluated OA treatment according to guidance generally report low uptake of ‘core’, first line non-pharmacological measures, such as weight loss advice, provision of patient information and aerobic and strengthening exercise [6–9]. The reasons for this are not clear, although likely to be influenced by a number of variables including awareness of the guidance [10].

Secondly, patient reported measures suggest the condition may be inadequately treated. A large survey of patients commissioned by Arthritis Care in the UK reports that patients experience long delays before they are diagnosed and that they don’t feel OA is a priority for the healthcare system [11]. More worryingly, the survey suggests nearly three quarters of people with OA are living with constant pain, with 40% of those surveyed reporting their treatment either ‘not very’ or ‘not’ effective.

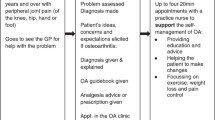

One significant barrier to treatment in OA, is choosing not to seek healthcare. A recent review suggests a number of patients with painful OA chose not to visit their GP; reasons for this include believing that OA is a normal part of ageing or perceiving a negative response from the GP [12]. However, when patients do visit their GP, little is known about what actually happens in the consultation. Understanding more about the consultation may further explain the reasons for the apparent gap between the guidance, and the positive view conveyed by OA experts and the apparent ‘real world’ experience.

This review aims to illuminate this issue, by summarising and reviewing existing literature regarding patients’ experiences of consultations regarding osteoarthritis in primary care, and comparing this with literature reporting GP attitudes and beliefs to OA. Understanding patient experience, while considering GPs views, may provide insight into aspects of the consultation that could be targeted for intervention with the aim of enhancing OA care, and this review is conducted in the context of a larger programme of work with that aim.

Methods

An initial literature search, performed as a scoping exercise identified relevant research using a range of methods including interviews, focus groups and surveys. Due to the diversity of studies, a narrative review was therefore felt to be most appropriate to confer the flexibility needed to review the relevant literature. A narrative review is described as a ‘first generation ‘traditional’ literature review; narrative reviews have a useful place for identifying themes and gaps in the literature and for informing direction of further research [13]. This review is underpinned by a systematic literature search; combining narrative and systematic methods has value in enhancing transparency and rigour of narrative reviews. The literature search was undertaken by searching relevant databases (Medline, CINAHL, Psychinfo, EMBASE and Google scholar), reference checking, manual searching of relevant journals and recommendations from experts. The search terms used specified the population of interest (patients with osteoarthritis), the setting (the primary care consultation with a general practitioner) and ‘experiences’. Search terms used are shown in Table 1. All MeSH headings relating to OA were used with the exception of OA spine; this review aimed to summarise the experiences of those with peripheral joint OA, and not back pain.

The initial research question aimed to compare patient and doctor consultation experiences; however, the first literature search, performed as a scoping exercise, revealed that papers exploring GPs’ perspectives addressed more abstract components of ‘experience’, and tended to report attitudes and beliefs, rather than ‘experience’ of consultations, per se. For this reason, attitudes and beliefs were added to the search string, and the research question changed accordingly. As in qualitative research generally, this review seeks to describe a range of phenomena, and with this in mind, inclusion criteria were deliberately non-restrictive. Papers were included if any of the empirical data in the results related to patient consultation experience, or GPs’ attitudes and beliefs regarding OA. However, only the findings relating to consultation experience or GP attitudes and beliefs were extracted for inclusion in the review. Quantitative studies reporting GP consultation behaviours only were excluded, for example, medical record reviews, unless additional methodology elicited attitudes and beliefs e.g. free text responses on a survey or additional GP interviews.

Papers were included if they concerned patients with a diagnosis of OA or if the population studied were aged over 45 and had a clinical syndrome of chronic peripheral joint pain without a specific clinical diagnosis of OA. These were included with the assumption that the majority of those included were likely to represent people with OA; in primary care research a clinical rather than radiographic indicator or diagnosis may be more pragmatic, and there is high discordance in the use of the label osteoarthritis [14]. The only exclusion criteria were as follows: non-English language paper; consultation experiences not described (patients); attitudes or beliefs not described (GPs).

To appraise the evidence, no single tool was appropriate for the range of methodologies; however, qualitative research appraisal was informed by the CASP tool [15]. Key themes were extracted from the relevant findings of the included papers by the first author and a narrative review approach [13] applied to the results.

Results and discussion

The search identified 552 papers, of which 22 papers were identified as relevant to the review. A PRISMA flow diagram demonstrating selection of papers in detailed in Figure 1. One of the four papers excluded at full text stage was a conference abstract that repeated findings of a paper already included; the other three did not describe consultation experience. The majority of included papers represented UK research (13) with the remainder constituting North American (5), European (3), and Australian (1) studies. The majority of studies evaluated patient experience (12), with the remainder investigating GP views (5) or a combination of the two (5). The majority of included studies used predominately qualitative methodology (interviews: 15; focus group: 5). A summary of the papers identified is shown in Table 2 including a summary of each study aim, the methods used, the relevant findings and limitations.

The evidence is grouped below under four themes derived from the included studies: diagnosis; explanations; management of the condition; and the doctor-patient relationship. Patient and doctor perspectives are discussed under each theme.

Diagnosis

The issues identified around diagnosis predominantly relate to delays in diagnosis and the diagnostic term or phrase used at the time of diagnosis. Patients describe long delays before being diagnosed in both UK and Canadian research [16–18] in addition to difficulty obtaining a diagnosis and ‘relief’ at symptoms being legitimised [19]. There is some evidence to suggest multiple visits prior to receiving a diagnosis may be a particular issue in younger patients [17].

‘Wear and tear’ has been reported by patients as conveying a range of negative meanings including ‘it’s your age’ and ‘nothing can be done for you’ [20], or that the physician who used the term is ‘giving up’ [21]. Busby [18] argues that the connection with ageing results in the phrase conferring inevitability. However, the phrase is not exclusively associated with negative connotations. Grime et al. found participants used it as ‘shorthand for normal bodily change’ and adopt a ‘use it or lose it’ philosophy to exercise; Grime et al. report the latter finding is in contrast to other reported research suggesting patients may avoid activity due to connotations of wear and tear [22].

In one UK study of GPs’ perceptions of OA, GPs reported withholding or ‘playing down’ the diagnosis, using ‘wear and tear’ in preference to osteoarthritis or degenerative arthritis, in order to either avoid upsetting the patient or prevent the adoption of a ‘sick role’ and increased disability [23]. ‘Wear and tear’ was reported by GP participants as a term that may facilitate acceptance on the part of the patient and that saves time; introducing the term osteoarthritis was felt to necessitate a more detailed explanation [23]. In one French study, GPs described their diagnostic priority as identifying inflammatory joint pain, with the precise nature of mechanical pain being considered unimportant and unrelated to treatment [24].

Explanations and patient information

There are a number of studies in which patients report that they have been told their joint pain/ arthritis is normal for their age [17, 18, 20, 24, 25], and is likely to deteriorate over time [17, 26]. Similarly, reports of being told ‘nothing can be done’ are common [17–20], and this has been described as a ‘fatalist’ viewpoint. Patients describe being encouraged to accept their symptoms and ‘live with it’ [20].

Some patient narratives do indicate a degree of acceptance of their symptoms and perseverance with daily activities. Beliefs about symptoms being ‘normal for age’ are moderated by shared experiences of friends and family, and the societal view of ageing [19, 26]. It is also worthy of note that patients holding beliefs that nothing could be done or that symptoms were ‘just’ age related have reported withholding symptoms from the GP [19, 27].

However, there is evidence of patients rejecting the notion that OA is age-related [28], particularly younger adults [17] who may search for alternative explanations [19].

In an interview study with 81 patients with knee OA, a general dissatisfaction with the ‘vague’ information about the condition is reported [24]. Dissatisfaction with the amount of explanation is also reported in other UK studies [29, 30], with a feeling that OA is low priority [30]. The lack of precision in explanations has been interpreted as both lack of interest and lack of knowledge on behalf of the doctor [24, 29]. Patients reported that more information regarding disease progression may facilitate self-management and coping [16].

Education regarding prognosis has been identified as a particular area of unmet need in patients with OA [21], underpinned by fear of lifelong pain, and of becoming disabled. Victor et al. [21] tested knowledge of 170 patients with OA and found that 51% agreed with the statement ‘most people with osteoarthritis end up in a wheelchair’.

General Practitioners have reported giving patients advice on likely outcomes, but in the same study avoidance of the term ‘osteoarthritis’ for fear of upsetting patients, appeared to be associated with a perception by GPs that OA does in fact have a poor outcome [23].

Some General Practitioner interview findings do concur with the patients’ reports regarding consultation experience, with some GPs holding the belief that OA is a normal part of ageing and inevitable [24]. GPs have also clearly expressed the view that OA is ‘not a disease’ [16, 24] and in some instances, that there was therefore not a need for patient education [16].

General Practitioners have reported reasons for not giving written information, including lack of availability of quality resources and limited time [31]. Time in the consultation has been reported as a barrier to information giving in other UK studies [16, 31], but did not appear to be an issue in a non-UK European study [32]. GPs have also reported their own knowledge needs as a barrier to information provision [24, 28, 33].

Management of condition

In considering management, a number of studies referred to priorities, barriers, and challenges in treating patients with OA.

For patients, pain management and fear of disability have been reported as consultation priorities [32]. Jinks et al. [20] reported that patients tended to make their own decisions about medications, implying that consultations did not seem to contain lengthy discussions about the pros and cons of medication. Gignac et al. [17] report patient concerns that medication masks rather than cures symptoms and dissatisfaction with the amount of explanation accompanying prescriptions. Fear of side effects is reported [24, 32] and the presence of co-morbidities has also been described as contributing to patient hesitancy to take medication, in addition, again to suboptimal communication around prescriptions [34]. Throughout these studies is a recurring belief among patients that they receive inadequate information and communication around prescriptions, and Alami et al. describe this as leading to suspicion of drugs [24]. Alami et al. also describe patient expectations, with those with more chronic symptoms seeking ‘cure’. Patients describe physicians communicating treatment options as ‘palliative’, causing patients to question the efficacy of ‘modern medicine’ [24].

Two studies of patient experience suggest practitioner focus on pharmacological intervention is ‘unwelcome’, suggesting patients want more information about other approaches [30, 34].

Patients in focus groups discussed the inconsistency in advice regarding referral for joint replacement [16]. Patients also expressed having inadequate knowledge to make choices about surgery and anxiety about feeling the decision was theirs [16]. Patients have reported care for OA to be reactive, and not proactive with some expressing difficulty in knowing when to return to the doctor for follow-up [16].

GPs feel that patient led follow up is appropriate [23], particularly if they also hold the view that OA is ‘not a disease’ [35]. Interestingly, this belief seemed to underpin a reluctance to refer to self-management programmes, with GPs not identifying OA a chronic disease with the same standing as diabetes, but as a condition with little or no opportunity for modification of outcomes [36].

General Practitioners also report pain control as the biggest challenge in a survey of OA management in the UK [31]. GPs in this study identified practice and logistical barriers to managing pain such as lack of specialist teams and time in the consultation, in addition to lack of training. In a German study, GPs talked about specific patient barriers to managing pain; for example, they reported patients either did not accept paracetamol as a treatment due to its common use or had already tried it [32]. Rosemann et al. [32] also described a reluctance among GPs to prescribe opiates for OA, considering that patients would automatically reject these ‘heavy’ drugs, in addition to GPs perceiving opiates were ‘over-treatment’ for OA.

With regard to lifestyle change such as promotion of exercise and weight loss, GPs have described getting patients to change their lifestyle as challenging [31] and described patients as generally unwilling to change, having ‘learned to live’ with their symptoms [32]. GPs have also expressed uncertainty regarding exercise prescriptions [28]. Lambert et al. [28] highlights the different perspectives of patients and physicians; in their study doctors were reported as valuing surgical options and medication in OA treatment, with the implication non-pharmacological, non-surgical treatments were less valued by physicians, than patients.

OA and the doctor-patient relationship

The need for doctors to value or legitimise symptoms emerges strongly from published studies [19, 22], with patients in one study describing that they have not been taken seriously [24]. Patients report feeling OA is not a priority [30].

Patients described the importance of the doctor-patient relationship in the study by Alami et al. [24] and the need for doctors to be patient centred. Kee [37] describes participants with OA ‘stay[ing] in charge’ by not taking medications recommended by GPs, or not seeing doctors again who had recommended joint replacement, when this was not favoured by the patient. However, this also represents a breakdown in communication and shared decision-making. As previously mentioned, Davis et al. [34] found that patients reported communication and unmet expectations as barriers to effective pain management, in addition to personal barriers such as comorbidities and emotional distress.

General Practitioners have reported feeling that the lack of therapeutic options or cure in OA threatens the doctor-patient relationship [18, 23]. Further evidence of this comes from GP reports of either requesting X-Rays or referring patients to secondary care, when they don’t believe it clinically indicated, in order to preserve the relationship [23, 32]. GPs may have resultant feelings of frustration [23] and feel that patients have ‘unrealistic expectations’ [28]. An alternative viewpoint is provided by Gignac et al. who suggest doctor and patient have different orientations; doctors may approach OA from a perspective of acceptance whereas patients may believe they have more power to exert control and influence over their symptoms [17]. Busby et al. [18] describe the GP as translator of knowledge, and suggest how tensions in the doctor-patient relationship may exist between biological and sociological knowledge; if a doctor has uncertainty about biological explanations he or she may favour sociological descriptors e.g. wear and tear.

GPs’ prioritisation of OA is described by Coar, with GPs reporting it as less important than other ‘life-threatening’ conditions such as ischaemic heart disease [23]. Coar [23] also discusses the notion that a common condition may be considered less important by GPs: ‘familiarity breeds contempt’.

Conclusions

A broad range of literature has been reviewed in order to understand what happens when patients consult with osteoarthritis. A strength of this review is the breadth of included literature, including a MPhil thesis, which has been particularly useful in illuminating the GP perspective.

From the literature reviewed, a number of issues have emerged. Firstly, patient studies indicate a range of patient-perceived negative talk that may occur in the consultation. This includes the phrase ‘wear and tear’ which may have negative connotations, reporting OA is something to be lived with and nothing can be done. The negative perception of ‘wear and tear’ is likely an unintended outcome of a term that GPs may choose with the best of intentions, to avoid causing alarm. However, patient preferences for diagnostic labelling are not clear. This review also highlights that negative comments about OA may relate to the GP’s underlying beliefs that OA is ‘not a disease’ and that it is likely to deteriorate. Importantly, negative talk may not always originate from the GP with evidence that patients may hold similar views. A need for primary care to endorse a more positive view of OA has previously been identified [38] and this review serves as a useful reminder for clinical practice of the impact of negative talk in the consultation.

Secondly, this review highlights marked divergence over management, between patient and doctor. Patients may have complex expectations and fears regarding treatment that are inadequately explored in the consultation. While patients seem keen to explore non-pharmacological options, GPs report frustration and lack of knowledge around issues to do with lifestyle change. When asked about challenges to management, GPs tend to report resource issues or time in the consultation, or patient factors, whereas patients report lack of communication. Both GPs and patients have identified knowledge deficit, and it is possible that enhanced management of OA requires an approach that addresses knowledge, communication and shared decision making, which in turn may promote greater self-management [39].

Finally, this review highlights the importance to patients of feeling that their joint pain is being taken seriously and validated. GPs that hold the belief that OA is a normal change may not adequately legitimise their patients’ symptoms and engage with management approaches. The failure to adequately validate a patient’s symptoms may lead to a downward spiral of discordance within the consultation, and this finding has resonance with work with patients’ with medically unexplained symptoms [40].

In considering the limitations of this review, it is worthy of note that the majority of cited studies concentrate on deficits in quality of care, and this may reflect publication bias to some extent. Some of the studies described are over 10 years old and may not accurately reflect the issues relevant at the current time, especially in light of new insights with regard disease pathophysiology, treatment and outcomes. Furthermore, the attitudes and beliefs of patients and doctors who agree to take time to participate in research about OA may not be representative of the population as a whole. Some of the qualitative research included had only brief mentions of a consultation with a GP, and it is possible that some of the views elicited were not entirely based on consultation experiences.

Patient preferences around the labelling of the condition, the nature of doctor explanations of osteoarthritis and discussion around management options (including the degree of shared decision making) have emerged as areas for further research. Given the limitations of the studies reviewed, observational research would be well placed to explore these issues further. Observing the consultation, and matching patient and doctor behaviours and reactions will go much further in unlocking the important ‘chain of events’, and the origin of any negative talk. In the meantime, practicing GPs may wish to reflect on the influence of negative statements on patient outcome, and whether training needs exist around the management of patients with osteoarthritis. Communication within the consultation is clearly linked to patient satisfaction, but whether interventions to enhance the doctor patient interaction influence other health outcomes remains to be seen [41].

Author information

ZP is a Clinical Lecturer and Honorary Consultant Rheumatologist and conducted this review as part of a PhD using mixed methods to explore the osteoarthritis consultation in primary care. This is part of a larger programme of work aiming to enhance the care of osteoarthritis in primary care. TS is a Senior Research fellow with an interest in consultation research, and supervisor to ZP. ABH is a Professor of Medical Education and Consultant Rheumatologist and PhD supervisor to ZP.

Abbreviations

- GP:

-

General Practitioner

- NHS:

-

National Health Service (United Kingdom)

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis.

References

Zhang W, Doherty M, Leeb B, Alekseeva L, Arden N, Bijlsma J, Dinçer F, Dziedzic K, Häuselmann H, Herrero-Beaumont G: EULAR evidence based recommendations for the management of hand osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2007, 66 (3): 377-388. 10.1136/ard.2006.062091.

Zhang W, Doherty M, Arden N, Bannwarth B, Bijlsma J, Gunther KP, Hauselmann HJ, Herrero-Beaumont G, Jordan K, Kaklamanis P, Leeb B, Lequesne M, Lohmander S, Mazieres B, Martin-Mola E, Pavelka K, Pendleton A, Punzi L, Swoboda B, Varatojo R, Verbruggen G, Zimmermann-Gorska I, Dougados M: EULAR evidence based recommendations for the management of hip osteoarthritis: report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2005, 64: 669-681. 10.1136/ard.2004.028886.

Mazieres B, Bannwarth B, Dougados M, Lequesne M: EULAR recommendations for the management of knee osteoarthritis. Report of a task force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials. Joint Bone Spine. 2001, 68: 231-240. 10.1016/S1297-319X(01)00271-8.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: The care and management of osteoarthritis in adult [CG59]. 2008, London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

Zhang W, Moskowitz R, Nuki G, Abramson S, Altman R, Arden N, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Brandt K, Croft P, Doherty M: OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008, 16 (2): 137-162. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.013.

Chevalier X, Marre JP, De Butler J, Hercek A: Questionnaire survey of management and prescription of general practitioners in knee osteoarthritis: a comparison with 2000 EULAR recommendations. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004, 22 (2): 205-212.

Porcheret M, Jordan K, Jinks C, Croft P: Primary care treatment of knee pain–a survey in older adults. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007, 46 (11): 1694-1700. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem232.

Linsell L, Dawson J, Zondervan K, Rose P, Carr A, Randall T, Fitzpatrick R: Population survey comparing older adults with hip versus knee pain in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2005, 55 (512): 192-198.

Cottrell E, Roddy E, Foster NE: The attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of GPs regarding exercise for chronic knee pain: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2010, 11: 4-10.1186/1471-2296-11-4.

Clarson LE, Nicholl BI, Bishop A, Edwards J, Daniel R, Mallen C: Should there be a Quality and Outcomes Framework domain for osteoarthritis? A cross-sectional survey in general practice. Qual Prim Care. 2013, 21 (2): 97-103.

Arthritis Care: OA Nation. 2012, London: Arthritis Care

Paskins Z, Sanders T, Hassell A: What influences patients with Osteoarthritis to consult their GP about their symptoms? A narrative review. BMC Fam Pract. 2013, 14 (1): 195-10.1186/1471-2296-14-195.

Pope C, Mays N, Popay J: Synthesizing Qualitative and Quantitative Research Evidence: a guide to methods. 2007, Maidenhead: Open University Press

Peat G, Greig J, Wood L, Wilkie R, Thomas E, Croft P: Diagnostic discordance: we cannot agree when to call knee pain'osteoarthritis'. Fam Pract. 2005, 22 (1): 96-

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP): Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_951541699e9edc71ce66c9bac4734c69.pdf,

Mann C, Gooberman-Hill R: Health care provision for osteoarthritis: concordance between what patients would like and what health professionals think they should have. Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63 (7): 963-972. 10.1002/acr.20459.

Gignac MAM, Davis AM, Hawker G, Wright JG, Mahomed N, Fortin PR, Badley EM: “What do you expect? You're just getting older”: a comparison of perceived osteoarthritis‒related and aging‒related health experiences in middle‒and older‒age adults. Arthritis Care Res. 2006, 55 (6): 905-912. 10.1002/art.22338.

Busby H, Williams G, Rogers A: 3 Bodies of knowledge: lay and biomedical understandings of musculoskeletal disorders. Sociol Health Illn. 1997, 19 (19B): 79-99.

Sanders C, Donovan JL, Dieppe PA: The significance and consequences of having painful and disabled joints in older age: co-existing accounts of normal and disrupted biographies. Sociol Health Illn. 2002, 24: 227-253. 10.1111/1467-9566.00292.

Jinks C, Ong BN, Richardson J: A mixed methods study to investigate needs assessment for knee pain and disability: population and individual perspectives. Bmc Musculoskeletal Disord. 2007, 8: 59-10.1186/1471-2474-8-59.

Victor CR, Ross F, Axford J: Capturing lay perspectives in a randomized control trial of a health promotion intervention for people with osteoarthritis of the knee. J Eval Clin Pract. 2004, 10 (1): 63-70. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2003.00395.x.

Grime J, Richardson JC, Ong BN: Perceptions of joint pain and feeling well in older people who reported being healthy: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2010, 60 (577): 597-603. 10.3399/bjgp10X515106.

Coar L: General Practitioners' understanding and perceptions of osteoarthritis: an exploratory study. 2004, UK: MPhil Thesis. Keele University

Alami S, Boutron I, Desjeux D, Hirschhorn M, Meric G, Rannou F, Poiraudeau S: Patients' and practitioners' views of knee osteoarthritis and its management: a qualitative interview study. PLoS ONE Elect Resour. 2011, 6 (5): e19634-10.1371/journal.pone.0019634.

Sanders C, Donovan JL, Dieppe PA: Unmet need for joint replacement: a qualitative investigation of barriers to treatment among individuals with severe pain and disability of the hip and knee. Rheumatology. 2004, 43: 353-357.

Turner A, Barlow J, Buszewicz M, Atkinson A, Rait G: Beliefs about the causes of osteoarthritis among primary care patients. Arthritis Care Res. 2007, 57 (2): 267-271. 10.1002/art.22537.

McHugh GA, Silman AJ, Luker KA: Quality of care for people with osteoarthritis: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2007, 16 (7b): 168-176. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01885.x.

Lambert BL, Butin DN, Moran D, Zhao SZ, Carr BC, Chen C, Kizis FJ: Arthritis Care: Comparison of Physicians' and Patient's Views. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 30 (2): 100-110. 10.1053/sarh.2000.9203.

Hill S, Dziedzic KS, Nio B: Patients' perceptions of the treatment and management of hand osteoarthritis: a focus group enquiry. Disabil Rehabil. 2011, 33 (19–20): 1866-1872.

Thomas MJ, Moore A, Roddy E, Peat G: 'somebody to say ''come on, we can sort this''': A qualitative study of health-seeking in older adults with symptomatic foot osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (United Kingdom). 2013, 52: 124-

Kingsbury SR, Conaghan PG: Current osteoarthritis treatment, prescribing influences and barriers to implementation in primary care. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2012, 1 (1): 1-9.

Rosemann T, Wensing M, Joest K, Backenstrass M, Mahler C, Szecsenyi J: Problems and needs for improving primary care of osteoarthritis patients: the views of patients, general practitioners and practice nurses. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord. 2006, 7 (1): 48-10.1186/1471-2474-7-48.

Glauser TA, Salinas GD, Roepke NL, Chad J, Reese A, Gutierrez G, Abdolrasulnia M: Management of mild-to-moderate osteoarthritis: A study of the primary care perspective. Postgrad Med. 2011, 123 (1): 126-134. 10.3810/pgm.2011.01.2254.

Davis GC, Hiemenz ML, White TL: Barriers to managing chronic pain of older adults with arthritis. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004, 34 (2): 121-126.

De Bock GH, Kaptein AA, Mulder JD: Dutch general practitioners' management of patients with distal osteoarthritic symptoms. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1992, 10 (1): 42-46. 10.3109/02813439209014034.

Pitt VJ, O'connor D, Green S: Referral of people with osteoarthritis to self-management programmes: barriers and enablers identified by general practitioners. Disabil Rehabil. 2008, 30 (25): 1938-10.1080/09638280701774233.

Kee CC: Living with osteoarthritis: Insiders' views. Appl Nurs Res. 1998, 11 (1): 19-26. 10.1016/S0897-1897(98)80041-4.

Dziedzic KS, Hill JC, Porcheret M, Croft PR: New models for primary care are needed for osteoarthritis. Phys Ther. 2009, 89 (12): 1371-1378. 10.2522/ptj.20090003.

Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K: Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002, 288: 1775-1779. 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775.

Wileman L, May C, Chew-Graham CA: Medically unexplained symptoms and the problem of power in the primary care consultation: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2002, 19 (2): 178-182. 10.1093/fampra/19.2.178.

Griffin SJ, Kinmonth A, Veltman MW, Gillard S, Grant J, Stewart M: Effect on health-related outcomes of interventions to alter the interaction between patients and practitioners: a systematic review of trials. Ann Fam Med. 2004, 2 (6): 595-608. 10.1370/afm.142.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2296/15/46/prepub

Acknowledgements

This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research Programme (Grant Reference Number RP-PG-0407-10386). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

The authors wish to acknowledge and thank Professor Peter Croft for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ZP conceived the review, conducted literature searches, conducted the narrative review and drafted the manuscript. TS and ABH contributed to the narrative review and the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Paskins, Z., Sanders, T. & Hassell, A.B. Comparison of patient experiences of the osteoarthritis consultation with GP attitudes and beliefs to OA: a narrative review. BMC Fam Pract 15, 46 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-46

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-46