Abstract

Background

To improve the management of hip or knee osteoarthritis (OA), a multidisciplinary guideline-based stepped-care strategy (SCS) with recommendations regarding the appropriate non-surgical treatment modalities and optimal sequence for care has been developed. Implementation of this SCS in the general practice may be hampered by the negative attitude of general practitioners (GPs) towards the strategy. In order to develop a tailored implementation plan, we assessed the GPs’ views regarding specific recommendations in the SCS and their working procedures with regard to OA.

Methods

A survey was conducted among a random sample of Dutch GPs. Questions included the GP’s demographical characteristics and the practice setting as well as how the management of OA was organized and whether the GPs supported the SCS recommendations. In particular, we assessed GP’s views regarding the effectiveness of 14 recommended and non-recommended treatment modalities. Furthermore, we calculated their agreement with 7 statements based on the SCS recommendations regarding the sequence for care. With a linear regression model, we identified factors that seemed to influence the GPs’ agreement with the SCS recommendations.

Results

Four hundred fifty-six GPs (37%) aged 30–65 years, of whom 278 males (61%), responded. Seven of the 11 recommended modalities (i.e. oral Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs, physical therapy, glucocorticoid intra-articular injections, education, lifestyle advice, acetaminophen, and tramadol) were considered effective by the majority of the GPs (varying between 95-60%). The mean agreement score, based on a 5-point scale, with the recommendations regarding the sequence for care was 2.8 (SD = 0.5). Ten percent of the variance in GPs’ agreement could be explained by the GPs’ attitudes regarding the effectiveness of the recommended and non-recommended non-surgical treatment modalities and the type of practice.

Conclusion

In general, GPs support the recommendations in the SCS. Therefore, we expect that their attitudes will not impede a successful implementation in general practice. Our results provide several starting points on which to focus implementation activities for specific SCS recommendations; those related to the prescription of pain medication and the use of X-rays. We could not identify factors that contribute substantially to GPs’ attitudes regarding the SCS recommendations regarding the sequence for care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) of the hip or knee is a common joint disorder causing pain and functioning impairment. The core treatment for OA, a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment modalities, is mainly performed in primary care. In the Netherlands, once the diagnosis had been established, it has been found that patients with OA are treated in general practice for approximately 82 months before they are referred to an orthopaedic department [1]. Although several clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) to manage hip or knee OA exist [2–6], diagnostic procedures, referrals, and use of treatment modalities observed in primary care tend to be inadequate [7–9]. In addition, a recent review depicts a notably low pass rate for quality indicators for OA care (interquartile range 29-41%) [10]. These findings support the conclusion that incorporation of CPGs into clinical practice is not that simple.

We have developed a multidisciplinary, guideline-based stepped-care strategy, known as BART, i.e. Beating Osteoarthritis, to improve the management of hip or knee OA [11]. Experts from each discipline involved in OA care, as well as representatives from patient organizations and professional associations, participated in the development. This stepped-care strategy (SCS) provides a framework for various health care providers and patients to manage hip or knee OA (see Table 1). In addition to the current CPGs that give recommendations about the appropriate non-surgical treatment modalities, the SCS focuses also on the optimal order in which to employ them. This sequence is presented in three steps. At each step, recommendations for diagnostic procedures, treatment modalities, and the length of treatment before evaluation are made. Consequently, more advanced options are only recommended if the options listed in previous steps have failed to produce satisfactory results. Despite a possible risk of delay for more advanced modalities, the SCS is a suitable approach for patients with hip or knee OA.

To implement this strategy, the views about the SCS recommendations and working procedures concerning OA care of general practitioners (GPs) need to be assessed and the barriers that prevent GPs from using the SCS need to be identified [12–14]. This knowledge can then be used to develop implementation activities tailored for GPs. The importance of such activities, created in response to identified barriers, has been demonstrated in a recent review that reported that tailored activities are more likely to improve professional practice than non-tailored activities [15]. Also, insight into the GPs’ views provides information concerning the strengths and weaknesses of current practice and heightens the perception of the need for change [13].

An approach based on a theoretical model can help to identify these barriers. Barriers are frequently grouped into social factors (including patients’ preferences), the clinicians’ attitudes, the implementation process, accessibility and format of the program, and external barriers of a practical nature [12, 16–18]. In this study, we assessed the attitudes towards the SCS recommendations expressed by GPs which could be a potential barrier to successful implementation of this strategy [19]: specifically, their attitudes regarding the effectiveness of recommended non-surgical treatment modalities for hip or knee OA and their degree of agreement with recommendations regarding the sequence for care. Considering the fact that each recommendation can be influenced by different factors [20], we will assess the attitudes towards several specific SCS recommendations.

The aim of this study is to describe the GPs’ attitudes with respect to the two key elements of the SCS: 1) their attitudes regarding the effectiveness of the recommended non-surgical treatment modalities and 2) their agreement with specific recommendations regarding the sequence for care. In particular, those factors, that could influence their agreement with these recommendations, will be identified and will be used to develop tailored made implementation activities for this target group.

Methods

General practitioners

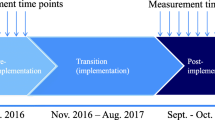

To estimate the prevalence of GPs who agree with the SCS recommendations with 95% confidence level and a maximal error margin of 5%, data of 369 GPs was needed for this cross-sectional study. Assuming a response rate of 30%, a random sample of 1230 GPs was drawn from all listed GPs in the Netherlands (about 8.900) by the Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research (NIVEL) in July 2011. The anonymous survey was sent to this sample, followed by a reminder after two weeks to maximize the response.

Survey

The survey consisted of questions regarding the GP’s characteristics and their practice setting, as well as the organization of OA management and the GP’s attitudes towards the SCS recommendations.

GP’s characteristics and their practice setting

The demographic characteristics included age, sex, length of time working (expressed in years), number of working hours (expressed in fulltime equivalents (fte)), and their field of special interest (e.g. in musculoskeletal disorders (yes/no)). Practice characteristics included type of practice (solo, duo, practice group, GP centre, and health centre), location of the practice (urban, suburban, or rural), practice size (expressed in number of registered patients), number of GPs working in practice (expressed in fte), presence of practice staff (e.g. practice nurse and assistant (yes/no)) as well as other health care providers in the practice (e.g. physical therapist, dietician, physiologist, pharmacist, social worker (yes/no)).

Organization of OA management

The organization of OA management in general practice was assessed by mapping the involvement of the GP, practice nurse, and practice assistant in the following care tasks: a) providing information, b) providing lifestyle advice, c) distributing patient information material from the Dutch College of General Practitioners (NHG), d) distributing other types of information, e) referral to a dietician, f) referral to a physical or exercise therapist, and g) evaluating results at the follow-up appointment.

In addition, we assessed the type of collaboration the GP had with other health care providers involved in OA care (physical or exercise therapists, dieticians, rheumatologists, and orthopaedic surgeons) by using three items: 1) participation in periodic meetings concerning individual OA patients (yes/no), 2) following protocols or agreements concerning specific working procedures to treat OA patients (yes/no), and 3) the frequency of contact (rarely, yearly, monthly, weekly) concerning individual OA patients.

GP’s attitudes towards the SCS recommendations

We studied GPs’ attitudes towards the two key elements of the SCS: their attitude concerning the appropriate treatment and their attitude concerning the optimal sequence. Therefore, we assessed which of the frequently-used treatment modalities were found to be effective in the treatment of hip or knee OA by the GPs. Furthermore, we assessed if GPs agreed with the sequence of care that is presented in the SCS recommendations.

GP’s attitudes regarding the effectiveness of fourteen frequently-used treatment modalities were scored on a 4-point Likert scale (i.e. not effective – effective) or not applicable (“no experience with the modality”). Eleven of these modalities are recommended in the SCS (education, lifestyle advice, acetaminophen, glucosaminesulphate, oral and topical Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), physical therapy, tramadol, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), hyaluronic acid, and glucocorticoid injections). Three other frequently-used modalities (massage, manual therapy, and other passive physical therapy treatment modalities, such as cold or heat therapy, ultrasound, laser therapy, or electrotherapy) are not recommended in the SCS, i.e. non-recommended modalities.

GP’s attitudes regarding the sequence for care was assessed by a 5-point Likert scale (i.e. strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree) for seven statements. These statements were based on the SCS recommendations and thus concerned the three areas of management: diagnosis (statement 1), treatment (statement 2–6), and evaluation (statement 7). Treatment modalities from all different steps of the SCS were covered: step 1 (statement 3), step 2 (statements 2 and 4), step 3 (statement 5), and “step 4” (statement 6).

Data analysis

We used descriptive statistics for the GP’s characteristics and their practice setting, the organization of OA management, and the GP’s attitudes towards the SCS recommendations.

In order to examine the collaboration of the GPs with other health care providers, we constructed two variables by combining items. First, we considered collaboration “structural” (yes/no), if the GP reported to have periodic meetings or reported to follow protocols or agreements concerning specific working procedures with any other health care provider. Second, we considered collaboration “ad hoc” (yes/no), if the GP had at least monthly contact with one or more of the other health care providers.

Furthermore, we constructed two indices to examine the GPs’ attitudes regarding the effectiveness of the fourteen frequently-used non-surgical treatment modalities. One index concerned their attitude regarding the effectiveness of the eleven modalities that are recommended in the SCS, while the other index concerned their attitude regarding the effectiveness of the three non-recommended treatment modalities. We calculated an average score for both indices based on the results on the 4-point Likert scales. If more than one-third of the items was missing (i.e. four or more items for the first index and two or more items for the second index), the scores (range of 0–3; in which 0 = “negative attitude” and 3 = “positive attitude” regarding the effectiveness of the corresponding modalities) were treated as being missing. We excluded items that were ‘not applicable’ from the average score.

Finally, we used linear regression models to assess univariable and multivariable associations between the GP’s agreement with recommendations regarding the sequence for care and the characteristics relating to the GPs, the practice, or organization of management. We constructed an overall index for GPs’ agreement with the seven statements by calculating the average score of items (range of 0–4; in which 0 = “no agreement” and 4 = “complete agreement” with the SCS recommendations). For that matter, the scores on the items in which the desired response was “disagree” were reversed. The scores were treated as being missing if more than one-third of the items was missing (i.e. three or more items). The results were expressed in betas with standard error (SE). All variables that showed univariable significance (p < 0.10) were entered simultaneously into a multivariable model. Statistical analyses were executed using STATA 10.0.

Results

Out of the 1230 approached GPs, 456 GPs (37%) responded to the survey. Differences between the main characteristics of the participating GPs and the total population of Dutch GPs [21] were limited to the number of working hours and location of practice (Table 2).

GP’s characteristics and their practice setting

Table 3 presents a summary of the characteristics of the participating GPs and their practice setting. Most participating GPs (62%) reported to have one or more fields of special interest. Palliative care (27%), diabetes mellitus (18%), asthma/COPD (17%) cardiovascular diseases (16%), and musculoskeletal disorders (15%) were the most frequently reported fields of interest.

Organization of OA management

Of the 403 GPs (88%) who have a practice nurse available, 73 GPs (18%) reported that their practice nurse is involved in the OA management: “providing lifestyle advice” was the most frequently reported performed task. Of the 440 GPs (96%) who have a practice assistant available, 79 GPs (18%) reported that their practice assistant is involved in OA management: their most frequently performed task in OA management was “handing out other kind of information”.

One hundred twenty-two GPs (27%) reported having “structural” collaboration (having periodic meetings or following protocols or agreements concerning specific working procedures) with other health care providers. Two hundred twenty-seven GPs (51%) reported having “ad hoc” (at least monthly) contact with other health care providers. Both, structural and ad hoc collaboration, were generally with a physical therapist. With regard to structural collaboration, 96 (98%) of the GPs who reported having periodic meetings reported those to be with physical therapists, and 52 (95%) of the GPs who reported following protocols or agreements concerning specific working procedures reported those to be with physical therapists. In addition, 214 GPs (95%) of the GPs who reported having ad hoc contact reported that to be with physical therapists. Thirteen (4%), 38 (10%), and 64 (16%) of the GPs reported having ad hoc contact with a dietician, rheumatologist, or orthopaedic surgeon, respectively.

GPs’ attitudes towards the SCS recommendations

Seven of the recommended modalities (i.e. oral NSAIDs, physical therapy, glucocorticoid intra-articular injections, education, lifestyle advice, acetaminophen, and tramadol) were considered effective by the majority of the GPs (varying between 95-60%) (Table 4). Fewer GPs found the non-recommended modalities to be effective (39-14%).

The highest level of agreement with SCS recommendations regarding the sequence for care was reported for the statements 2 and 4; 86% of the GPs (strongly) disagreed with the statement ‘NSAIDs should only be prescribed if there is radiological OA’ and 91% of the GPs (strongly) disagreed with the statement ‘Physical therapy should only be prescribed if there is radiological OA’ (Table 5). The highest level of disagreement with the SCS recommendations was reported for the statement 1 and 3: 48% of the GPs (strongly) agreed with statement ‘X-ray is necessary to diagnose OA’ and 21% of the GPs (strongly) agreed with the statement ‘NSAIDs should be the first choice of pain medication in patients with OA’. The average score (SD) for the seven statements regarding the sequence for care, was 2.8 (0.4) on a 5-point scale.

Determinants for a GP’s agreement with the SCS

An univariable association was found between GP’s agreement with the SCS recommendations regarding the sequence for care and four of the characteristics relating to the GP. These were the attitudes towards the effectiveness of recommended and non-recommended treatment modalities, the type of practice, and whether the GP had structural collaboration with other health care providers (Table 6). The multivariable analysis revealed that a positive attitude towards the effectiveness of recommended modalities, a negative attitude regarding the effectiveness of non-recommended modalities, and working in a duo or group practice were significantly associated with a higher agreement with SCS recommendations regarding the sequence for care. Together these three variables explained 9.5% of the variance in this model.

Discussion

In general, the GPs’ attitudes were in concordance with SCS recommendations regarding the non-surgical treatment modalities and the sequence for care; seven of the eleven recommended treatment modalities were considered effective for patients with hip or knee OA by the great majority of the GPs and five of the seven SCS recommendations regarding the sequence for care were consistent with the attitudes of most GPs. However, we found a notably high number of GPs who reported that tramadol, topical NSAIDs, and glucosamine were not effective and who reported that non-recommended modalities were effective in patients with hip or knee OA. Also, many GPs considered an X-ray necessary to diagnose OA and considered NSAIDs the drug of first choice (instead of acetaminophen). GPs’ agreement with SCS recommendations regarding the sequence for care was only weakly associated with a positive attitude towards the effectiveness of recommended modalities, a negative attitude towards the effectiveness of non-recommended modalities, and working in a duo or group practice.

As mentioned above, many GPs reported thought that several types of pain medication that are recommended in the SCS are not effective in patients with hip or knee OA. An explanation for the negative attitude towards tramadol could be the high prevalence of side effects [22, 23], which may result to therapy switching or discontinuation, and thus a negative evaluation of its effectiveness by GPs [24, 25]. Furthermore, the GPs’ negative attitudes towards the effectiveness of topical NSAIDs, glucosamine, and hyaluronic acid intra-articular injections might be explained by the discrepancies between the recommendations of the SCS and the Dutch NHG-standard for non-traumatic knee complaints in adults [6]. As the SCS was developed through a consensus procedure based on several national and international guidelines, the SCS recommendations differed slightly from those of the Dutch NHG-guideline. For example, the NHG-standard recommends GPs not to use glucosamine in patients with OA and gives no recommendations regarding topical NSAIDs, while the SCS does. In general, NHG-standards have a great impact on GPs’ knowledge [20] and thus could have influenced GPs’ attitudes regarding the effectiveness of these modalities. Another possible explanation for the GPs’ negative attitude towards topical NSAIDs, glucosamine, and hyaluronic acid intra-articular injections is that these are not reimbursed in the Netherlands. The GPs’ positive attitude regarding the non-recommend modalities, like manual therapy and other passive modalities, could be explained by the preferences for these modalities by the patients and physical therapists. This explanation is supported by the fact that these modalities are frequently used in patients with OA [26].

The SCS points out that medical history and physical examination are sufficient to diagnose (symptomatic) hip or knee OA, as radiographic confirmation of OA has little impact on the management, particularly in the early stages of the disease [3, 5, 27]. Interestingly, many GPs reported that X-ray is necessary to diagnose hip or knee OA. This finding is concordant with other studies that assessed GPs’ behaviour for ordering X-rays in the management of OA or back pain [28–30]. The GPs legitimise their use of radiographs by expressing the view that it aids the discussion of management with the OA patient, is required for specialist referral, and can be used to reduce referrals [29]. Moreover, GPs believe that X-rays provide reassurance to patients which can outweigh the risks; furthermore, denying X-rays could adversely affect the doctor-patient relationship [30]. Although patients who have had X-ray seemed to be more satisfied, they reported more pain, lower overall health status, though no difference in disability, and consult their doctor more frequently [30, 31]. In light of this, GPs need to be informed about the limited value of X-rays in early OA.

We found three factors that are associated with the GPs’ attitude regarding the sequence for care. The first two factors, that concern the GPs’ agreement with the effectiveness of recommended and non-recommended treatment modalities, suggest that GPs who are aware of the effectiveness of these modalities agree with the SCS recommendations regarding the sequence for care. This result might be explained by the fact that these recommendations were based on evidence outlined in CPGs. Furthermore, the association between the GPs’ attitude regarding the sequence for care and the type of practice is in concordance with other studies suggesting that the organizational setting of the practice is the most consistent predictor of the GPs’ behaviour and can influence GPs’ performance [32, 33]. Generally, the isolated physician in solo practice provides a more limited range of services and show lower levels of clinical competence [33]. Moreover, GPs in solo practices appear to have a more aggressive treatment style than those physicians in group practices, which might be explained by financial incentives, lack of peer influences and availability of colleagues for informal consultation [32].

This study is not without limitations. First of all, only 10% of the variance in GPs’ agreement could be explained by factors related to the GP, the practice, or the management organization for OA patients. We did not examine the contribution of person-related or situational factors, e.g., the GPs’ experience, the patients’ preferences, local infrastructures, and rules or laws on the sequence for care; these factors have been named in literature as potentially able to influence GP’s attitudes [12, 16]. Secondly, our study does not cover all professionals because the research aim of this study was restricted to GP’s views and working procedures, while implementation of the multidisciplinary SCS should involve different disciplines. However, this study is part of an umbrella project, the BART-project, which aims to implement the SCS in practice and evaluate the implementation process in one region of the Netherlands, in preparation for the nation-wide implementation. Therefore, the views and working procedures of patients and other health care providers will be studied and described at a later date. Thirdly, the self-designed survey was tailored to our target population and not validated. Fourthly, we measured the GP’s attitudes regarding recommendations of the SCS and not the GP’s actual behaviour. Although a positive relation between attitude and behaviour can be assumed [34] our results do not give insight into the extent that the current clinical practice is concordant with the recommendations of the SCS. Consequently, there might be other barriers that impede a successful implementation. Finally, the response rate (37%), although relatively high for these kind of surveys among GPs, can raise some concerns regarding the validity and generalizability of our findings. Although we did not find large differences in several demographic and practice-related characteristics between the responders and the total population of Dutch GPs, we are aware that non-response bias could have affected the results. It has been stated that “serial” non-responders to GP surveys tent to be older, less likely to possess a postgraduate medical qualification, or belong to a practice that is involved with postgraduate or undergraduate training. [35] As we expect that additional education is associated with a more positive attitude to evidence-based practice, it could be hypothesized that our findings are an overestimation of the degree of agreement with the SCS recommendations.

Conclusions

Given the above-mentioned findings, the GPs’ attitude regarding recommendations in the SCS is not an insurmountable barrier for implementing the SCS in general practice. GPs are supportive of the recommendations regarding the effectiveness of treatment modalities and the sequence for care. Potential targets for implementation are improving the GPs’ knowledge regarding the effectiveness and optimal sequence for diagnostic procedures and treatment modalities, particularly in GPs who are working in a solo practice. Therefore, we recommend to include these themes in the GP-guideline and embed these in the program of the (post-graduate) training program and/or post-academic training for GPs. We did not identify any barriers that substantially contribute to GPs’ agreement with the SCS recommendations regarding the sequence for care. Further efforts should be taken to identify barriers that could prevent GPs from using the SCS.

References

Paans N, van der Veen WJ, van der Meer K, Bulstra SK, van den Akker-Scheek I, Stevens M: Time spent in primary care for hip osteoarthritis patients once the diagnosis is set: a prospective observational study. BMC Fam Pract. 2011, 12: 48-10.1186/1471-2296-12-48.

National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions: Osteoarthritis: national clinical guideline for care and management in adults. 2008, London: Royal College of Physicians

Zhang W, Doherty M, Arden N, Bannwarth B, Bijlsma J, Gunther KP, Hauselmann HJ, Herrero-Beaumont G, Jordan K, Kaklamanis P: EULAR evidence based recommendations for the management of hip osteoarthritis: report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2005, 64: 669-681. 10.1136/ard.2004.028886.

Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, Abramson S, Altman RD, Arden N, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Brandt KD, Croft P, Doherty M: OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part I: critical appraisal of existing treatment guidelines and systematic review of current research evidence. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007, 15: 981-1000. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.06.014.

Dutch Orthopadic Association: Diagnostiek en behandeling van heup- en knieartrose. (Diagnostics and treatment of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee). 2007, Kwaliteitsinstituut: Kwaliteitsinstituut voor de Gezondheidszorg (CBO)

Belo JN, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Raaijmakers AJ, Van der Wissel F, Opstelten W: NHG Standaard Niet traumatische knieproblemen bij volwassenen (eerste herziening). (NHG-Standard: Non-traumatic knee complaints in adults (first revision)). Huisarts Wet. 2008, 51: 229-240. 10.1007/BF03086753.

McHugh GA, Campbell M, Luker KA: Quality of care for individuals with osteoarthritis: a longitudinal study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012, 18: 534-541. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01616.x.

Ng NT, Heesch KC, Brown WJ: Strategies for managing osteoarthritis. Int J Behav Med. 2012, 19: 298-307. 10.1007/s12529-011-9168-3.

Snijders GF, den Broeder AA, van Riel PL, Straten VH, de Man FH, van den Hoogen FH, van den Ende CH: Evidence-based tailored conservative treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis: between knowing and doing. Scand J Rheumatol. 2011, 40: 225-231. 10.3109/03009742.2010.530611.

Askari M, Wierenga PC, Eslami S, Medlock S, de Rooij SE, Abu-Hanna A: Assessing quality of care of elderly patients using the ACOVE quality indicator set: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e28631-10.1371/journal.pone.0028631.

Smink AJ, van den Ende CH, Vliet Vlieland TP, Swierstra BA, Kortland JH, Bijlsma JW, Voorn TB, Schers HJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Dekker J: “Beating osteoARThritis”: development of a stepped care strategy to optimize utilization and timing of non-surgical treatment modalities for patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2011, 30: 1623-1629. 10.1007/s10067-011-1835-x.

Grol R: Implementing guidelines in general practice care. Qual Health Care. 1992, 1: 184-191. 10.1136/qshc.1.3.184.

Grol R, Wensing M: Effectieve implementatie: een model. Implementatie. Edited by: Effectieve verbetering van de patiëntenzorg. 2006, Maarssen: Elsevier, 65-91. 3

Watkins C, Harvey I, Langley C, Gray S, Faulkner A: General practitioners’ use of guidelines in the consultation and their attitudes to them. Br J Gen Pract. 1999, 49: 11-15.

Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, Shaw EJ, Cheater F, Flottorp S, Robertson N: Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010, CD005470-

Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, Rubin HR: Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999, 282: 1458-1465. 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458.

Carlsen B, Bringedal B: Attitudes to clinical guidelines–do GPs differ from other medical doctors?. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011, 20: 158-162. 10.1136/bmjqs.2009.034249.

Stewart RE, Vroegop S, Kamps GB, van der Werf GT, Meyboom-de JB: Factors influencing adherence to guidelines in general practice. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003, 19: 546-554.

Farquhar CM, Kofa EW, Slutsky JR: Clinicians’ attitudes to clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review. Med J Aust. 2002, 177: 502-506.

Lugtenberg M, Zegers-van Schaick JM, Westert GP, Burgers JS: Why don’t physicians adhere to guideline recommendations in practice?. An analysis of barriers among Dutch general practitioners. Implement Sci. 2009, 4: 54-

Hingstman L, Kenens RJ: Figures from the registration of practitioners. 2012, Utrecht: Poll 2011

Langley C, Faulkner A, Watkins C, Gray S, Harvey I: Use of guidelines in primary care–practitioners’ perspectives. Fam Pract. 1998, 15: 105-111. 10.1093/fampra/15.2.105.

Rosenthal NR, Silverfield JC, Wu SC, Jordan D, Kamin M: Tramadol/acetaminophen combination tablets for the treatment of pain associated with osteoarthritis flare in an elderly patient population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004, 52: 374-380. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52108.x.

Gehling M, Hermann B, Tryba M: Meta-analysis of dropout rates in randomized controlled clinical trials: opioid analgesia for osteoarthritis pain. Schmerz. 2011, 25: 296-305. 10.1007/s00482-011-1057-9.

Gore M, Sadosky A, Leslie D, Tai KS, Seleznick M: Patterns of therapy switching, augmentation, and discontinuation after initiation of treatment with select medications in patients with osteoarthritis. Clin Ther. 2011, 33: 1914-1931. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.10.019.

Walsh NE, Hurley MV: Evidence based guidelines and current practice for physiotherapy management of knee osteoarthritis. Musculoskeletal Care. 2009, 7: 45-56. 10.1002/msc.144.

Swierstra BA, Bijlsma JWJ, de JJA B, Kuijpers T: Richtlijn ‘Diagnostiek en behandeling van heup- en knieartrose’. (Guideline ‘Diagnostics and treatment of osteoarthrosis of the hip and knee’). Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2009, 153.,

Glazier RH, Dalby DM, Badley EM, Hawker GA, Bell MJ, Buchbinder R, Lineker SC: Management of common musculoskeletal problems: a survey of Ontario primary care physicians. CMAJ. 1998, 158: 1037-1040.

Morgan B, Mullick S, Harper WM, Finlay DB: An audit of knee radiographs performed for general practitioners. Br J Radiol. 1997, 70: 256-260.

Baker R, Lecouturier J, Bond S: Explaining variation in GP referral rates for x-rays for back pain. Implement Sci. 2006, 1: 15-10.1186/1748-5908-1-15.

Kendrick D, Fielding K, Bentley E, Miller P, Kerslake R, Pringle M: The role of radiography in primary care patients with low back pain of at least 6 weeks duration: a randomised (unblinded) controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. 2001, 5: 1-69.

Landon BE, Reschovsky J, Reed M, Blumenthal D: Personal, organizational, and market level influences on physicians’ practice patterns: results of a national survey of primary care physicians. Med Care. 2001, 39: 889-905. 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00014.

Lockyer JM: Physician performance: The roles of knowledge, skill, and environment. Teach Learn Med. 1992, 4: 86-96. 10.1080/10401339209539540.

Ajzen I, Fishbein M: Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. 1980, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall

Stocks N, Gunnell D: What are the characteristics of general practitioners who routinely do not return postal questionnaires: a cross sectional study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000, 54: 940-941. 10.1136/jech.54.12.940.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2296/14/33/prepub

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

All authors participated in the design of the manuscript. AJS carried out the data collection and preformed the statistical analysis. AJS and CHM drafted the manuscript. All authors helped to interpret the data and revise the manuscript. Furthermore, all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Smink, A.J., Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M., Dekker, J. et al. Agreement of general practitioners with the guideline-based stepped-care strategy for patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract 14, 33 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-33

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-33