Abstract

Background

According to the Word Health Organization, patients who can benefit from palliative care should be identified earlier to enable proactive palliative care. Up to now, this is not common practice and has hardly been addressed in scientific literature. Still, palliative care is limited to the terminal phase and restricted to patients with cancer. Therefore, we trained general practitioners (GPs) in identifying palliative patients in an earlier phase of their disease trajectory and in delivering structured proactive palliative care. The aim of our study is to determine if this training, in combination with consulting an expert in palliative care regarding each palliative patient's tailored care plan, can improve different aspects of the quality of the remaining life of patients with severe chronic diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure and cancer.

Methods/Design

A two-armed randomized controlled trial was performed. As outcome variables we studied: place of death, number of hospital admissions and number of GP out of hours contacts.

Discussion

We expect that this study will increase the number of identified palliative care patients and improve different aspects of quality of palliative care. This is of importance to improve palliative care for patients with COPD, CHF and cancer and their informal caregivers, and to empower the GP. The study protocol is described and possible strengths and weaknesses and possible consequences have been outlined.

Trial Registration

The Netherlands National Trial Register: NTR2815

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) palliative care is 'an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual' [1]. A first challenge evoked by this definition is the early identification of a patient who may benefit from palliative care. Although the WHO-recommendations have been accepted worldwide, no scientific papers have been published yet on how to identify patients who could potentially benefit from an earlier start of a palliative care in general practice. A literature review of Qaseem et al. did not identify any validated tools that predict the optimal timing to initiate palliative care services in general practice,[2] despite the fact that a lot of research has been undertaken to elucidate the prediction of mortality, survival, and prognostication for patients with advanced cancer and non-cancer diseases [3–10]. For patients not recognized as being in a palliative phase an individualized well-considered plan of action is missing [11, 12].

Several illness trajectories have been described for people with progressive chronic illnesses [13, 14]. For none of these trajectories the right moment to start palliative care has been defined yet. Particularly regarding patients with non-malignant diseases, such as advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and congestive heart failure (CHF), recognizing or defining the moment when palliative care should be taken in consideration seems difficult (Figure 1) [15, 16]. In a national questionnaire among multiple palliative care providers the lack of prognostic indicators and clinical triggers for starting end of life care appeared to be the most important missing link in applying palliative care in primary care [17]. By integrating palliative care into curative care practices or combining palliative care with disease-oriented management earlier in the disease trajectory, chronically ill patients nearing the end of life reported improved satisfaction with care and demonstrated less acute interventions and were more likely to die at home [18, 19].

What is the moment to start palliative care?, a modified figure of Lynn and Adamson[37].

The second challenge in bringing the WHO definition into clinical practice, for which early identification is a prerequisite, is a structured proactive palliative care planning. Palliative care programs appeared to reduce symptom distress and improve patient and family satisfaction. Important elements of structured proactive palliative care proved to be coaching the patient to make choices regarding future interventions or restrictions,[20–22] consulting caregivers,[18] eliciting values and addressing the psychological, existential and social context of patient and informal caregiver [23, 24]. By proactive planning death at home could be enhanced, [25–27] the number of unforeseen transfers decreased,[28] hospital lengths of stay and aggressive interventions diminished and consequently costs and utilization decreased [28–30].

For GPs a structured proactive palliative care planning is a challenge, as patients with an advanced chronic disease are often under supporting care of the disease-specific specialists until far in the disease trajectory [31]. The GPs should pick up their role as coordinator of palliative care against the mainstream of disease-oriented interventions [32, 33]. Several studies concluded that when a GP is part of a team, palliative care improves on different aspects; for patient, informal carer and the participating GP [34, 35].

Aims of the study

Research questions

In this study we aim to answer the following questions:

Does early identification and proactive palliative care planning of palliative patients by the GP influence

-

1.

Place of death, number of transitions and number of contacts with the out of hours primary care service?

-

2.

Quality of life of patients and their informal caregivers and prescriptions?

-

3.

GP satisfaction with the delivered palliative care and their own assessment of their ability to provide palliative care?

The objective of this report is to present the study protocol used for the data collection in 2009 and 2010. We describe the protocol of the study, provide a description of the intervention, the methodology and the baseline characteristics of the participating GPs. The described methodology will also serve as a reference for future publications about this study.

Methods/Design

Study design

We performed a two-armed randomized controlled trial.

We studied the following hypothesis: H0: training GPs in early identification of palliative care patients and proactive care planning will not increase the percentage of patients that die at home, will not reduce the amount of hospital admissions and will not reduce the number of contacts with the out of hours primary care service. This hypothesis will be rejected if the training has a significant positive effect on these aspects of care.

Power calculation

Sample size was based on number of contacts with the out of hours primary care service. To detect a difference between the intervention and the control group with a power of 80% and an alpha error of 0.05 minimum sample size was 96 patients in both groups when 20% reduction in out of hours contacts was considered.

Participants

GPs in two comprehensive cancer centre (IKO and IKZ) regions in the South-East of the Netherlands were invited by mail to participate in the study. After one month a reminder was send to non-responders. Excluded were GPs who are consultant in palliative care or who are locum. GPs that wanted to participate were stratified for degree of urbanization and working hours (part-time or full-time) and were randomized assigned to the intervention or the control condition by an independent statistician. To prevent contamination, those GPs working together in the same practice were placed in the same study group.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted after approval of the research ethics committee of the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre in accordance with the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Acts (WMO). Patient and physician anonymity was guaranteed throughout the registration and data entry process. Patients and their informal caregiver were invited to participate by their GP. If they agreed to participate in the longitudinal study they received a patient information letter and an informed consent form. Trial registration has been obtained. (The Netherlands National Trial Register: NTR2815)

The intervention

The intervention for the GPs in the experimental condition consisted of three consecutive parts.

Part one consisted of a five-hours training in early identification of palliative patients and proactive care planning. This training was provided by two experienced GPs with a specialization in palliative care and an extended experience in teaching. Early identification was based on two tools, developed in an earlier stage of the project and described elsewhere (submitted). The first tool is a plasticized card (Table 1) with indicators to identify and recognize patients with respectively COPD, CHF and cancer as being in a stage that palliative care should be considered, the so-called 'Radboud Indicators Palliative Care Needs' (RADPAC). GPs were trained in 1) checking actual problems of the patient in a structured way at the moment of identification, 2) considering potential problems that could be expected in the (near) future and 3) foretelling the most likely scenarios on deterioration and death. A previously developed tool (Table 2) could be used as an abstract of the content of the training and could be used to structure the discussion with the patient and their informal caregiver, and to explore their actual en potential problems and needs (Proactive Palliative Care Planning Card (PPCPC)). The aim was a shared proactive policy to deliver specific, proper and individualized palliative care planning.

The second part of the intervention consisted of a coaching session for the GPs with a physician specialized in palliative care regarding each identified patient included in the study. In this session the GP received feedback and suggestions on the proposed proactive palliative care plan, potential future problems and potential scenarios of deterioration and death.

The third part of the intervention consisted of two peer group sessions of the intervention GPs, eight and ten months after the initial training session. In these sessions the main focus was patient-GP communication techniques regarding having the first conversation with the patient about palliative care (and thus about end of life issues). GPs also had the opportunity to exchange experiences on this topic. Data for process description were collected during the first year after T0. Effect evaluation took place in April 2011.

Control group

GPs in the control group were asked to provide usual care. They were not trained and had no access to RADPAC, nor to the PPCPC. Consultation by telephone with the palliative care helpdesk of the Comprehensive Cancer Centre was possible as usual. This service is available 24/7 for all GPs in the two comprehensive cancer centre regions in the South-East of the Netherlands; mostly these consultations are on problems in the terminal phase for which the GP needs specialised advice for acute problems. For GPs in the control group a training will be organized after the intervention study is closed.

Data collection

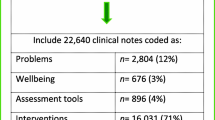

At the start of the study (t = 1), GPs in the intervention group were asked to use RADPAC to screen the medical records of all patients in their practice to identify patients with COPD, CHF or cancer who potentially could benefit from a palliative care approach. They were instructed to continue to use RADPAC each time new data of a patient with CHF, COPD or progressive cancer was available. In 2011, anonymous data were collected retrospectively from the medical records of all patients that had a non-acute death during the intervention period, as well in the intervention as in the control practices (t = 2). All deceased patients who were diagnosed with CHF, COPD and/or cancer were included (Figure 2). Each non-planned (out of hour) contact and hospital or nursing home admission during the study was derived from the medical record and registered as well as place of death and if the patient had been identified as being in the palliative trajectory. Besides, qualitative data were collected concerning proactive care planning in both study groups.

Outcomes

GPs of both study groups were invited to extract data of all patients that died during the observational period from the medical records: demographics, disease history, place of death, hospital admissions and out of hours consultations. Of each participating GP, demographic characteristics, practice characteristics and their interest in palliative care were collected (Table 3).

Data management and plan of statistical analysis

All data were entered in a database and analysed with SPSS 16.0. In both study groups, all patients who died during the inclusion and observation period of the study of a non-acute death, were included in the retrospective analysis. Intervention and control group will be compared on the main outcomes (place of death, number of transitions and out of hours contact, amount of identified patients). Recruitment rates and drop-out rates will be calculated. In case denominators prove to be significantly correlated with the outcome of the main study question, an Anova will be performed to identify potential related or independent factors. Multilevel analysis will be performed.

Discussion

The present study has been designed to assess the effects of training GPs in early identification and a proactive palliative care approach regarding patients with COPD, CHF or cancer.

Strengths

Up to now, hardly any data are available about implementing the 2002 WHO-definition for palliative care. To our knowledge this is the first intention to treat RCT that assesses the effect of training GPs in early identification and using a proactive holistic palliative care approach, which are the main aspects of this definition. The training for the GPs in the intervention group was standardised and piloted, to minimize differences between the two trainers and to be available for future courses. The tools that the GPs in the intervention group could use for helping to identify palliative patients in an earlier stage than usual and to structure the proactive care planning, were developed in a scientifically sound way. Results will be published in peer-reviewed scientific journals and will be communicated to relevant clinician associations.

Weaknesses

Those GPs that were interested to take part in the study, probably have a special interest in palliative care. Besides, as there is a lot of attention for proactive palliative care in medical journals and in Dutch policy, GPs in the control group might be influenced by new information or followed courses. This implies that it might be difficult to find significant differences between intervention and control group. As patients were identified by their own GP, we were not able to influence this process directly.

We did not choose to collect prospective patient data in the control group, as this would be a sort of intervention. Therefore, effect measurement took place retrospectively. GPs in both intervention and control group were asked to collect retrospective data from their digital patient information system. This implies that we do not have patient data of non-responding GPs.

We performed a multifaceted intervention: a combination of training GPs and offering them tools to facilitate early identification and proactive care planning. Usually, multifaceted interventions are more effective than single interventions,[36] but the relative impact of each component of the intervention cannot be established.

Conclusion

The present study will increase the knowledge about the effect of training GPs in early identification and a proactive palliative care approach. This knowledge is of importance to improve palliative care for patients with COPD, CHF and cancer and their informal caregivers, as well as to empower the GP. Here, the study protocol is described and possible strengths and weaknesses and possible consequences have been outlined.

References

World Health Organisation (WHO): 2002, Ref Type: Internet Communication, [http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/]

Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, Casey DE, Cross JT, Owens DK, et al: Evidence-based interventions to improve the palliative care of pain, dyspnea, and depression at the end of life: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008, 148: 141-146.

Glare P: Clinical predictors of survival in advanced cancer. J Support Oncol. 2005, 3: 331-339.

Glare P, Sinclair CT: Palliative Medicine Review: Prognostication. J Palliat Med. 2008, 11: 84-103. 10.1089/jpm.2008.9992.

Glare P, Sinclair C, Downing M, Stone P, Maltoni M, Vigano A: Predicting survival in patients with advanced disease. Eur J Cancer. 2008, 44: 1146-1156. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.02.030.

Maltoni M, Caraceni A, Brunelli C, Broeckaert B, Christakis N, Eychmueller S, et al: Prognostic factors in advanced cancer patients: evidence-based clinical recommendations--a study by the Steering Committee of the European Association for Palliative Care. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23: 6240-6248. 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.866.

Zapka JG, Moran WP, Goodlin SJ, Knott K: Advanced heart failure: prognosis, uncertainty, and decision making. Congest Heart Fail. 2007, 13: 268-274. 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2007.07184.x.

Oga T, Nishimura K, Tsukino M, Sato S, Hajiro T: Analysis of the factors related to mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: role of exercise capacity and health status. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003, 167: 544-549. 10.1164/rccm.200206-583OC.

Marti S, Munoz X, Rios J, Morell F, Ferrer J: Body weight and comorbidity predict mortality in COPD patients treated with oxygen therapy. Eur Respir J. 2006, 27: 689-696. 10.1183/09031936.06.00076405.

Llobera J, Esteva M, Rifa J, Benito E, Terrasa J, Rojas C, et al: Terminal cancer. duration and prediction of survival time. Eur J Cancer. 2000, 36: 2036-2043. 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00291-4.

Farquhar M, Grande G, Todd C, Barclay S: Defining patients as palliative: hospital doctors' versus general practitioners' perceptions. Palliat Med. 2002, 16: 247-250. 10.1191/0269216302pm520oa.

Stuart B, D'Onofrio CN, Boatman S, Feigelman G: CHOICES: promoting early access to end-of-life care through home-based transition management. J Palliat Med. 2003, 6: 671-683. 10.1089/109662103768253849.

Lunney JR, Lynn J, Hogan C: Profiles of older medicare decedents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002, 50: 1108-1112. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50268.x.

Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Sheikh A: Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ. 2005, 330: 1007-1011. 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007.

McKinley RK, Stokes T, Exley C, Field D: Care of people dying with malignant and cardiorespiratory disease in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2004, 54: 909-913.

Fitzsimons D, Mullan D, Wilson JS, Conway B, Corcoran B, Dempster M, et al: The challenge of patients' unmet palliative care needs in the final stages of chronic illness. Palliat Med. 2007, 21: 313-322. 10.1177/0269216307077711.

Shipman C, Gysels M, White P, Worth A, Murray SA, Barclay S, et al: Improving generalist end of life care: national consultation with practitioners, commissioners, academics, and service user groups. BMJ. 2008, 337: a1720-10.1136/bmj.a1720.

Brumley RD, Enguidanos S, Cherin DA: Effectiveness of a home-based palliative care program for end-of-life. J Palliat Med. 2003, 6: 715-724. 10.1089/109662103322515220.

Abarshi E, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Donker G, Echteld M, Van den BL, Deliens L: General practitioner awareness of preferred place of death and correlates of dying in a preferred place: a nationwide mortality follow-back study in the Netherlands. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009, 38: 568-577. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.12.007.

Rainone F, Blank A, Selwyn PA: The early identification of palliative care patients: preliminary processes and estimates from urban, family medicine practices. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2007, 24: 137-140. 10.1177/1049909106296973.

McAlister FA, Stewart S, Ferrua S, McMurray JJ: Multidisciplinary strategies for the management of heart failure patients at high risk for admission: a systematic review of randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004, 44: 810-819.

Schofield P, Carey M, Love A, Nehill C, Wein S: 'Would you like to talk about your future treatment options'? Discussing the transition from curative cancer treatment to palliative care. Palliat Med. 2006, 20: 397-406. 10.1191/0269216306pm1156oa.

Payne S, Smith P, Dean S: Identifying the concerns of informal carers in palliative care. Palliat Med. 1999, 13: 37-44. 10.1191/026921699666872524.

Chochinov HM: Dying, dignity, and new horizons in palliative end-of-life care. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006, 56: 84-103. 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.84.

Block van den L, Deschepper R, Drieskens K, Bauwens S, Bilsen J, Bossuyt N, et al: Hospitalisations at the end of life: using a sentinel surveillance network to study hospital use and associated patient, disease and healthcare factors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007, 7: 69-10.1186/1472-6963-7-69.

Gomes B, Higginson IJ: Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: systematic review. BMJ. 2006, 332: 515-521. 10.1136/bmj.38740.614954.55.

Enguidanos SM, Cherin D, Brumley R: Home-based palliative care study: site of death, and costs of medical care for patients with congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2005, 1: 37-56. 10.1300/J457v01n03_04.

Wiese CH, Vossen-Wellmann A, Morgenthal HC, Popov AF, Graf BM, Hanekop GG: Emergency calls and need for emergency care in patients looked after by a palliative care team: Retrospective interview study with bereaved relatives. BMC Palliat Care. 2008, 7: 11-10.1186/1472-684X-7-11.

Gelfman LP, Meier DE, Morrison RS: Does Palliative Care Improve Quality? A Survey of Bereaved Family Members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008

Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, Nilsson ME, Maciejewski ML, Earle CC, et al: Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009, 169: 480-488. 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.587.

McGrath P: Care of the haematology patient and their family--the GP viewpoint. Aust Fam Physician. 2007, 36: 779-81. 784

Meijler WJ, Van HF, Otter R, Sleijfer DT: Educational needs of general practitioners in palliative care: outcome of a focus group study. J Cancer Educ. 2005, 20: 28-33.

Groot MM, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Verhagen SC, Crul BJ, Grol RP: Obstacles to the delivery of primary palliative care as perceived by GPs. Palliat Med. 2007, 21: 697-703. 10.1177/0269216307083384.

Mitchell GK: How well do general practitioners deliver palliative care? A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2002, 16: 457-464. 10.1191/0269216302pm573oa.

McWhinney IR, Stewart MA: Home care of dying patients. Family physicians' experience with a palliative care support team. Can Fam Physician. 1994, 40: 240-246.

Grol R, Wensing M: Implementatie, Effectieve verbetering van de patientenzorg. 2006, Maarssen: Elsevier gezondheidszorg, third

Lynn J, Adamson DM: Living well at the end of life. Adapting health care to serious chronic illness in old age. 2003, Washington: RAND health, Ref Type: Report

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2296/12/123/prepub

Acknowledgements

This project was financially supported by a grant of the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development--ZonMw, TheHague. Project number: 1150.0002

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Authors' contributions

BT led the drafting of this paper and together with MG, SV and YE the development of the protocol. YE and KV were the initiators of the study and obtained funding. YE and MG did study supervision. YE, MG, SV, CW and KV were responsible for critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read, revised and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Thoonsen, B., Groot, M., Engels, Y. et al. Early identification of and proactive palliative care for patients in general practice, incentive and methods of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract 12, 123 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-12-123

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-12-123