Abstract

Background

The development and evaluation of complex interventions in healthcare has obtained increased awareness. The Medical Research Council’s (MRC) framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions and its update offers guidance for researchers covering the phases development, feasibility/piloting, and evaluation. Comprehensive reporting of complex interventions enhances transparency and is essential for researchers and policy-makers. Recently, a set of 16 criteria for reporting complex interventions in healthcare (CReDECI) was published. The aim of this study is to evaluate the reporting quality in publications of complex interventions adhering to either the first or the updated MRC framework, and to evaluate the applicability of CReDECI.

Methods

A systematic PubMed search was conducted. Two reviewers independently checked titles and abstracts for inclusion. Trials on complex interventions adhering to the MRC framework and including an evaluation study in English and German were included. For all included trials and for all publications which reported on phases prior to the evaluation study, related publications were identified via forward citation tracking. The quality of reporting was assessed independently by two reviewers using CReDECI. Inter-rater agreement and time needed to complete the assessment were determined.

Results

Twenty-six publications on eight trials were included. The number of publications per trial ranged from 1 to 6 (mean 3.25). The trials demonstrate a good reporting quality for the criteria referring to the development and feasibility/piloting. For the criteria addressing the introduction of the intervention and the evaluation, quality of reporting varied widely. Two trials fulfilled 7 and 8 items respectively, five trials fulfilled one to five items and one trial offered no information on any item. The mean number of items with differing ratings per trial was two. The time needed to rate a trial ranged from 30 to 90 minutes, depending on the number of publications.

Conclusions

Adherence to the MRC framework seems to have a positive impact on the reporting quality on the development and piloting of complex interventions. Reporting on the evaluation could be improved. CReDECI is a practical instrument to check the reporting quality of complex interventions and could be used alongside design-specific reporting guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Researching complex interventions in healthcare and nursing has gained increased awareness following the publication of the UK Medical Research Council’s (MRC) framework for development and evaluation of complex interventions in 2000 [1] and its update in 2008 [2, 3]. The MRC framework defined complex interventions as interventions comprising several components which may act either independently or inter-dependently [2]. However, there is no distinct boundary in the classification of whether an intervention is complex or not. Characteristics of complex interventions are, for example, the number of different professions or organisational levels targeted by the intervention and/or the degree of flexibility permitted for the intervention [4].

While the first framework [1] implied a linear approach comprising one preclinical and four clinical phases, the updated framework [2, 3] builds on a circular model which gives a better reflection of the flexibility or even non-linearity of the research process. However, both versions cover the same methodological steps of development, piloting and evaluation of a complex intervention, and the long-term implementation after the complex intervention has demonstrated its effectiveness. Also, both frameworks emphasise that the development of a complex intervention should include a theoretical basis and a clear description of the intended change processes. Prior to the evaluation, the intervention should be piloted in the target setting and its feasibility has to be tested. The evaluation study should not only focus on effectiveness and cost-effectiveness but also include the evaluation of the intended change process by investigating the dose delivered, fidelity and reach of the intervention (process evaluation) [5–7]. Thus, the development and evaluation of complex interventions requires several studies using different methods and study designs [1–4].

Comprehensive reporting of all steps of the development and evaluation of a complex intervention is crucial. Sufficient information must be available for the judgement of the intervention’s clinical benefits, for replication, or for adaption of an intervention to different settings or countries [8–10]. However, several analyses revealed shortcomings of the reporting of core aspects of complex intervention research, e.g. regarding the theoretical basis and assumptions guiding the development and piloting of the intervention, and the description of intervention delivery [10–13]. These studies evaluated interventions on defined topics, e.g. care of people after stroke [13] and reduction of physical restraints in geriatric care [12], or specific methodological aspects of research on complex interventions [10, 11]. An evaluation of the reporting quality of a sample of systematically identified complex interventions explicitly adhering to the MRC framework has not been performed so far.

We have recently published a list of specific criteria for reporting complex interventions in order to offer a structured guidance for researchers and authors covering the first three phases of the MRC framework [14]. In contrast to other reporting guidelines (e.g. CONSORT), CReDECI does not comprise design-specific items. The development and evaluation of complex interventions requires the use of different methodological approaches and the criteria list includes only items covering these specific methodological aspects [1–4, 14]. Therefore, CReDECI should be used alongside established study design-specific reporting statements.

Employing the CReDECI criteria, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the reporting quality of the development and evaluation of complex interventions adhering to the MRC framework. The second aim was to test the applicability of the criteria list.

Methods

Literature search and study selection

All trials which adhered to the MRC framework were eligible for inclusion. We use the term ‘trial’ for the entire research process covering development, piloting and evaluation of a complex intervention and all related publications or reports. Adherence to the MRC framework was defined as citing either the first version [1] or the updated framework [3] as methodological guide for the development and evaluation of a complex intervention. According to the aim of our study to test the applicability of all CReDECI criteria, the included trials should have undergone a controlled evaluation study.

The following inclusion criteria were defined: The intervention was (I) labelled as ‘complex intervention’, (II) developed and evaluated adhering to the MRC framework, and (III) a controlled evaluation study was published. All citations retrieved by database searching and ‘snowballing’ techniques were screened independently by two reviewers (RM and GB) and checked for inclusion. We conducted a database search and used snowballing techniques to identify relevant publications since we expected several publications reporting on different phases of the same trial [15].

A systematic search in Medline (via PubMed) was performed in April 2012. Medline was searched because this database is the primary resource for clinicians and researchers and most journals publishing evaluation studies of health care interventions are covered. The search was limited to German and English publications of the last ten years. We explored several search strategies to select the adequate search terms. Finally, we used a combination of terms related to complex interventions and to the MRC framework (the complete search strategy is described in Additional file 1). Since we used additional snowballing technique to identify further relevant publications, we believe the search strategy employed to be sufficiently specific. In a second step, we conducted forward citation tracking (via Scopus and Google Scholar). For all citations identified by the database search which reported on the development and/or piloting of a complex intervention we checked whether a publication of an evaluation study was available. In a third step, we identified the associated publications of the included trials, e.g. publications on the interventions’ development.

CReDECI

The CReDECI list [14] was developed based on a systematic literature review of methodological publications on complex intervention research and the updated MRC framework and reviewed by experts in the field. The criteria list is divided into three sections: development (n = 6 items), feasibility and piloting (n = 2 items), and introduction of the intervention and evaluation (n = 8 items). In contrast to most of the available reporting guidelines, the CReDECI list does not comprise items targeting a specific study-design, since the development and evaluation of complex interventions requires different study designs conducted subsequently or in parallel [2]. Instead, CReDECI focuses on criteria covering the core elements that are specific for the research of complex interventions. An overview of the criteria and their explanation is presented in Table 1.

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers (RM, GB) applied CReDECI to all publications related to the respective included trials. For each item it was recorded whether sufficient information was provided in any publication. In order to distinguish between sufficient and insufficient information, the raters assessed whether the information provided was judged as comprehensive. The information to the individual items may have been included in several publications. However, if a minimum of comprehensive information was offered, the items were rated as fulfilled. We did not assess the degree of comprehensibility.

The results of the independent ratings were compared and agreement between both raters was checked. Thereafter, differences in the ratings were discussed in order to reach consensus. If results on planned parts of the trial were missing (e.g. economic evaluation or process evaluation), the corresponding author was contacted. The number of trials fulfilling the criteria was calculated. The absolute number of different ratings per trial was determined with regard to inter-rater reliability as well as to the time spent on completing the list (i.e. mean time of both raters).

Results

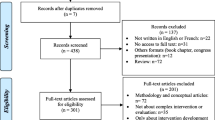

A total of 274 publications were identified via database search and forward citation tracking. Eight trials met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Main reasons for exclusion were that the interventions were not labelled as complex or the studies did not adhere to the MRC framework. A total of 26 publications were identified as reporting on the eight included trials. In two cases, authors were contacted for missing information. The mean number of publications per trial was 3.25 (range 1 to 6). For one trial, only one publication was available [16]. Four trials were conducted in UK [16–19], two in Ireland [20, 21] and one in Germany [22] and the Netherlands [23], respectively. Most of the complex interventions offered structured approaches for improving the quality of care for patients with chronic or complex conditions. Target groups were people suffering from a stroke [16, 19], cancer [18, 22], coronary heart disease [20], or diabetes mellitus Type 2 [21], patients at risk from prescription and medication management errors in general practice [17], and frail elderly people [23]. The interventions offered improved care concepts or pathways [17, 19, 20, 22] or alternative or modified forms of information or support [16, 18, 21] e.g. peer support groups for patients and/or their relatives [21]. Table 2 presents an overview of the included trials and the underlying interventions. The quality of reporting on development and piloting of the intervention was judged as good (Table 3). Seven out of eight trials reported on all six items referring to the intervention’s development [17–23] and one trial reported on three items [16]. Most trials presented sufficient information on the feasibility and pilot phase. Concerning the introduction and evaluation phase, the quality of reporting varied. Only one trial reported on all eight items [21] and one trial on seven items [17]. Five trials reported on one to five items [18–20, 22, 23] and one trial offered no information on any item [16].

The number of items with different ratings per trial ranged from 0–5 with a mean of 2. The two reviewers disagreed on 16 out of the total of 128 ratings (12.5%). The time needed to rate a trial ranged from 30 to 90 minutes, depending on the number of publications per trial.

Discussion

We identified a small number of trials whose authors explicitly stated having adhered to the MRC framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions [2]. The quality of reporting in these trials was judged as good for the intervention development and piloting phases. Thus, our findings are contrary to previous analyses of the quality of reporting on complex interventions [12, 13, 41]. However, the trials included in our sample are more likely to fulfil the CReDECI criteria, since all trials confirmed adherence to the MRC framework. For the evaluation phase, quality of reporting varied. While two trials reported on nearly all criteria, six trials offered information only on half of the items or even less. These results confirm the findings from previous studies [9, 11, 12, 42]. Only half of the trials included an evaluation of the implementation process (CReDECI criterion 12). However, this information is required in order to get a deeper understanding of the effects of the evaluation and to describe barriers and facilitators influencing the intervention’s implementation. A process evaluation should be an integral part of the evaluation of complex interventions [2, 5, 6]. Only half of the trials offered information on the characteristics of the care delivered in the control group, which was often only described as usual or standard care. The lack of information hampers the replication of studies and the adaption of the intervention to different settings or countries [9, 10].

The integration of the local context and detailed information on the process evaluation has recently been described as frequently underreported [43, 44]. In our sample only a small number of trials included a process evaluation but most trials offered information on the integration of the context in the intervention’s development. However, we did not assess the completeness of the information provided.

The CReDECI list has proven its applicability and practicability. A high rate of agreement was reached by both reviewers. The time needed for assessment varied, depending on the number of publications per trial. Since both reviewers were familiar with complex interventions research and the MRC framework, application of the CReDECI list by untrained users might be more time-consuming.

The currently available reporting guidelines specifically address a defined study design, offering recommendations to improve the reporting of design-specific methodological aspects [45]. The CReDECI list employs a different approach since it comprises items covering three phases of complex interventions’ research: development, feasibility/piloting, and introduction of the intervention and evaluation. However, we recommend the additional use of design-specific reporting guidelines alongside the CReDECI list. Currently, a CONSORT extension for social and psychological interventions is being developed [46]. This extension might be a valuable supplementation to the CReDECI list.

Limitations of study

Although Medline includes a great number of journals on healthcare research, the search in only one database might be judged as limitation. Further publications not indexed in Medline were identified through forward and backward citation tracking. Thus, it is most likely that we have identified the majority of publications on the development and evaluation of complex intervention explicitly referring to the MRC framework.

In this study, we assessed whether the criteria were fulfilled. Therefore, our analysis offers an overview about relevant aspects of complex interventions’ development and evaluation which were considered in the trials included. However, this analysis offers no judgement on the quality of the information provided.

We included only a small number of trials, since our inclusion criteria were rather strict. Therefore, readers must be aware that the results of our analysis do not represent the reporting quality of publications on complex interventions in general.

Conclusions

In this study, adhering to the MRC framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions seems to have a positive impact on the quality of reporting of the complex interventions’ development and feasibility/piloting. These results are in contrast to former analysis [10–13]. Reporting on the evaluation phase could still be improved.

The CReDECI list seems to be a practical instrument for checking the quality of reporting in publications on complex interventions. It could be used alongside established design-specific reporting guidelines such as the CONSORT statement. To further validate the CReDECI list, a formal consensus process with researchers and stakeholders is scheduled.

Abbreviations

- MRC:

-

UK medical research council.

References

Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, Kinmonth AL, Sandercock P, Spiegelhalter D, Tyrer P: Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ. 2000, 321: 694-696. 10.1136/bmj.321.7262.694.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M: Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance. 2008, http://www.mrc.ac.uk/complexinterventionsguidance,

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M, Medical Research Council Guidance: Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008, 337: a1655-10.1136/bmj.a1655.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M: Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013, 50: 587-592. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.010.

Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T, Gold L: Methods for exploring implementation variation and local context within a cluster randomised community intervention trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004, 58: 788-793. 10.1136/jech.2003.014415.

Oakley A, Strange V, Bonell C, Allen E, Stephenson J, RIPPLE Study Team: Process evaluation in randomised controlled trials of complex interventions. BMJ. 2006, 332: 413-416. 10.1136/bmj.332.7538.413.

Spillane V, Byrne MC, Byrne M, Leathem CS, O’Malley M, Cupples ME: Monitoring treatment fidelity in a randomized controlled trial of a complex intervention. J Adv Nurs. 2007, 60: 343-352. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04386.x.

Armstrong R, Waters E, Moore L, Riggs E, Cuervo LG, Lumbiganon P, Hawe P: Improving the reporting of public health intervention research: advancing TREND and CONSORT. J Public Health. 2008, 30: 103-109. 10.1093/pubmed/fdm082.

Egan M, Bambra C, Petticrew M, Whitehead M: Reviewing evidence on complex social interventions: appraising implementation in systematic reviews of the health effects of organisational-level workplace interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009, 63: 4-11.

Shepperd S, Lewin S, Straus S, Clarke M, Eccles MP, Fitzpatrick R, Wong G, Sheikh A: Can we systematically review studies that evaluate complex interventions?. PLoS Med. 2009, 6: e1000086-10.1371/journal.pmed.1000086.

Mayo-Wilson E: Reporting implementation in randomized trials: proposed additions to the consolidated standards of reporting trials statement. Am J Public Health. 2007, 97: 630-633. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.094169.

Möhler R, Richter T, Köpke S, Meyer G: Interventions for preventing and reducing the use of physical restraints in long-term geriatric care - a Cochrane review. J Clin Nurs. 2012, 21: 3070-3081. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04153.x.

Redfern J, McKevitt C, Wolfe CD: Development of complex interventions in stroke care: a systematic review. Stroke. 2006, 37: 2410-2419. 10.1161/01.STR.0000237097.00342.a9.

Möhler R, Bartoszek G, Köpke S, Meyer G: Proposed criteria for reporting the development and evaluation of complex interventions in healthcare (CReDECI): guideline development. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012, 49: 40-46. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.08.003.

Greenhalgh T, Peacock R: Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ. 2005, 331: 1064-1065. 10.1136/bmj.38636.593461.68.

Tilling K, Coshall C, McKevitt C, Daneski K, Wolfe C: A family support organiser for stroke patients and their carers: a randomised controlled trial. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005, 20: 85-91. 10.1159/000086511.

Avery AJ, Rodgers S, Cantrill JA, Armstrong S, Cresswell K, Eden M, Elliott RA, Howard R, Kendrick D, Morris CJ, Prescott RJ, Swanwick G, Franklin M, Putman K, Boyd M, Sheikh A: A pharmacist-led information technology intervention for medication errors (PINCER): a multicentre, cluster randomised, controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2012, 379: 1310-1319. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61817-5.

Strong V, Waters R, Hibberd C, Murray G, Wall L, Walker J, McHugh G, Walker A, Sharpe M: Management of depression for people with cancer (SMaRT oncology 1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2008, 372: 40-48. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60991-5.

Wolfe CD, Redfern J, Rudd AG, Grieve AP, Heuschmann PU, McKevitt C: Cluster randomized controlled trial of a patient and general practitioner intervention to improve the management of multiple risk factors after stroke: stop stroke. Stroke. 2010, 41: 2470-2476. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.588046.

Murphy AW, Cupples ME, Smith SM, Byrne M, Byrne MC, Newell J, SPHERE study team: Effect of tailored practice and patient care plans on secondary prevention of heart disease in general practice: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009, 339: b4220-10.1136/bmj.b4220.

Smith SM, Paul G, Kelly A, Whitford DL, O’Shea E, O’Dowd T: Peer support for patients with type 2 diabetes: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2011, 342: d715-10.1136/bmj.d715.

Klinkhammer-Schalke M, Koller M, Steinger B, Ehret C, Ernst B, Wyatt JC, Hofstädter F, Lorenz W, Regensburg QoL Study Group: Direct improvement of quality of life using a tailored quality of life diagnosis and therapy pathway: randomised trial in 200 women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012, 106: 826-838. 10.1038/bjc.2012.4.

Faes MC, Reelick MF, Melis RJ, Borm GF, Esselink RA, Rikkert MG: Multifactorial fall prevention for pairs of frail community-dwelling older fallers and their informal caregivers: a dead end for complex interventions in the frailest fallers. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011, 12: 451-458. 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.11.006.

Avery AJ, Rodgers S, Cantrill JA, Armstrong S, Elliott R, Howard R, Kendrick D, Morris CJ, Murray SA, Prescott RJ, Cresswell K, Sheikh A: Protocol for the PINCER trial: a cluster randomised trial comparing the effectiveness of a pharmacist-led IT-based intervention with simple feedback in reducing rates of clinically important errors in medicines management in general practices. Trials. 2009, 10: 28-10.1186/1745-6215-10-28.

Avery AJ, Rodgers S, Cantrill JA, Armstrong S, Boyd M, Cresswell K, Eden M, Elliott R, Franklin M, Howard R, Hippisley-Cox J, Kendrick D, Morris CJ, Murray SA, Prescott RJ, Putman K, Swanwick G, Tuersley L, Turner T, Vinogradova Y, Sheikh A: PINCER trial. Report for the department of health patient safety research portfolio 2010. Adv Physiol Educ. http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-mds/haps/projects/cfhep/psrp/finalreports/PS024PINCERFinalReportOctober2010.pdf,

Sharpe M, Strong V, Allen K, Rush R, Maguire P, House A, Ramirez A, Cull A: Management of major depression in outpatients attending a cancer centre: a preliminary evaluation of a multicomponent cancer nurse-delivered intervention. Br J Cancer. 2004, 90: 310-313. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601546.

Bower P, Gilbody S, Richards D, Fletcher J, Sutton A: Collaborative care for depression in primary care. Making sense of a complex intervention: systematic review and meta-regression. Br J Psychiatry. 2006, 189: 484-493. 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.023655.

Redfern J, Rudd AD, Wolfe CD, McKevitt C: Stop Stroke: development of an innovative intervention to improve risk factor management after stroke. Patient Educ Couns. 2008, 72: 201-209. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.03.006.

Byrne M, Cupples ME, Smith SM, Leathem C, Corrigan M, Byrne MC, Murphy AW: Development of a complex intervention for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in primary care using the UK medical research council framework. Am J Manag Care. 2006, 12: 261-266.

Corrrigan M, Cupples ME, Smith SM, Byrne M, Leathem CS, Clerkin P, Murphy AW: The contribution of qualitative research in designing a complex intervention for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in two different healthcare systems. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006, 6: 90-10.1186/1472-6963-6-90.

Murphy AW, Cupples ME, Smith SM, Byrne M, Leathem C, Byrne MC, The SPHERE Study: Secondary prevention of heart disease in general practice: protocol of a randomised controlled trial of tailored practice and patient care plans with parallel qualitative, economic and policy analyses [ISRCTN24081411]. Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2005, 6: 11-10.1186/1468-6708-6-11.

Gillespie P, O’Shea E, Murphy AW, Byrne MC, Byrne M, Smith SM, Cupples ME: The cost-effectiveness of the SPHERE intervention for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2010, 26: 263-271. 10.1017/S0266462310000358.

Paul G, Smith SM, Whitford D, O’Kelly F, O’Dowd T: Development of a complex intervention to test the effectiveness of peer support in type 2 diabetes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007, 7: 136-10.1186/1472-6963-7-136.

Paul GM, Smith SM, Whitford DL, O’Shea E, O’Kelly F, O’Dowd T: Peer support in type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial in primary care with parallel economic and qualitative analyses: pilot study and protocol. BMC Fam Pract. 2007, 8: 45-10.1186/1471-2296-8-45.

Gillespie P, O’Shea E, Paul G, O’Dowd T, Smith SM: Cost effectiveness of peer support for type 2 diabetes. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012, 28: 3-11. 10.1017/S0266462311000663.

Koller M, Klinkhammer-Schalke M, Ehret C, Steinger B, Ernst B, Hofstädter F, Lorenz W, Mitglieder des Qualitätszitkels; Advisory Board: [Diagnosis and therapy of illness-related quality of life in breast cancer patients. Protocol of a randomized clinical trial at the Regensburg tumour centre]. Z Arztl Fortbild Qualitatssich. 2006, 100: 175-182.

Klinkhammer-Schalke M, Koller M, Wyatt JC, Steinger B, Ehret C, Ernst B, Hofstädter F, Lorenz W: Quality of life diagnosis and therapy as complex intervention for improvement of health in breast cancer patients: delineating the conceptual, methodological, and logistic requirements (modeling). Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008, 393: 1-12.

Klinkhammer-Schalke M, Koller M, Ehret C, Steinger B, Ernst B, Wyatt JC, Hofstädter F, Lorenz W, Regensburg QoL Study Group: Implementing a system of quality-of-life diagnosis and therapy for breast cancer patients: results of an exploratory trial as a prerequisite for a subsequent RCT. Br J Cancer. 2008, 99: 415-422. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604505.

Faes MC, Reelick MF, Esselink RA, Rikkert MG: Developing and evaluating complex healthcare interventions in geriatrics: the use of the medical research council framework exemplified on a complex fall prevention intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010, 58: 2212-2221. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03108.x.

Reelick MF, Faes MC, Esselink RA, Kessels RP, Olde Rikkert MG: How to perform a preplanned process evaluation for complex interventions in geriatric medicine: exemplified with the process evaluation of a complex falls-prevention program for community-dwelling frail older fallers. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011, 12: 331-336. 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.01.006.

Thompson C, Stapley S: Do educational interventions improve nurses’ clinical decision making and judgement? a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011, 48: 881-893. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.12.005.

Schroter S, Glasziou P, Heneghan C: Quality of descriptions of treatments: a review of published randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2012, 2: e001978-10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001978.

Grant A, Treweek S, Dreischulte T, Foy R, Guthrie B: Process evaluations for cluster-randomised trials of complex interventions: a proposed framework for design and reporting. Trials. 2013, 14: 15-10.1186/1745-6215-14-15.

Wells M, Williams B, Treweek S, Coyle J, Taylor J: Intervention description is not enough: evidence from an in-depth multiple case study on the untold role and impact of context in randomised controlled trials of seven complex interventions. Trials. 2012, 13: 95-10.1186/1745-6215-13-95.

Moher D, Weeks L, Ocampo M, Seely D, Sampson M, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Miller D, Simera I, Grimshaw J, Hoey J: Describing reporting guidelines for health research: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011, 64: 718-742. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.013.

Department of social policy and Intervention: A CONSORT extension for social and psychological interventions. http://www.spi.ox.ac.uk/research/centre-for-evidence-based-intervention/consort-study.html,

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/13/125/prepub

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the provision of unpublished information by the study authors (Andrew Murphy and Mary Byrne; Miriam Faes).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

Study design: RM, GM; data collection and analysis: RM, GB. Manuscript preparation: RM, GM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Möhler, R., Bartoszek, G. & Meyer, G. Quality of reporting of complex healthcare interventions and applicability of the CReDECI list - a survey of publications indexed in PubMed. BMC Med Res Methodol 13, 125 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-125

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-125