Abstract

Background

While there is some consensus on methods for investigating statistical and methodological heterogeneity, little attention has been paid to clinical aspects of heterogeneity. The objective of this study is to summarize and collate suggested methods for investigating clinical heterogeneity in systematic reviews.

Methods

We searched databases (Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, and CONSORT, to December 2010) and reference lists and contacted experts to identify resources providing suggestions for investigating clinical heterogeneity between controlled clinical trials included in systematic reviews. We extracted recommendations, assessed resources for risk of bias, and collated the recommendations.

Results

One hundred and one resources were collected, including narrative reviews, methodological reviews, statistical methods papers, and textbooks. These resources generally had a low risk of bias, but there was minimal consensus among them. Resources suggested that planned investigations of clinical heterogeneity should be made explicit in the protocol of the review; clinical experts should be included on the review team; a set of clinical covariates should be chosen considering variables from the participant level, intervention level, outcome level, research setting, or others unique to the research question; covariates should have a clear scientific rationale; there should be a sufficient number of trials per covariate; and results of any such investigations should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

Though the consensus was minimal, there were many recommendations in the literature for investigating clinical heterogeneity in systematic reviews. Formal recommendations for investigating clinical heterogeneity in systematic reviews of controlled trials are required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Systematic reviews sometimes apply statistical techniques to combine data from multiple studies resulting in a meta-analysis. Meta-analyses result in a point estimate, the summary treatment effect, together with a measure of the precision of results (e.g., a 95% confidence interval). These measures of precision represent the degree of variability or heterogeneity in the results among included studies. There are several possible sources of variability or heterogeneity among studies that are included in meta-analyses. Variability in the participants, the types or timing of outcome measurements, and intervention characteristics may be termed clinical heterogeneity; variability in the trial design and quality is typically termed methodological heterogeneity; variability in summary treatment effects between trials is termed statistical heterogeneity [1]. Methodological and clinical sources of heterogeneity contribute to the magnitude and presence of statistical heterogeneity [1].

Methodological heterogeneity hinges on aspects of implementation of the individual trials and how they differ from each other. For example, trials that do not adequately conceal allocation to treatment groups may result in overestimates in the meta-analytic treatment effects [2]. Significant statistical heterogeneity arising from methodological heterogeneity suggests that the studies are not all estimating the same effects due to different degrees of bias.

Clinical heterogeneity arises from differences in participant characteristics (e.g., sex, age, baseline disease severity, ethnicity, comorbidities), types or timing of outcome measurements, and intervention characteristics (e.g., dose and frequency of dose [1]). This heterogeneity can cause significant statistical heterogeneity, inaccurate summary effects and associated conclusions, misleading decision makers and others. As such, systematic reviewers need to consider how best to handle sources of heterogeneity [1]. For example, preplanned subgroup analyses, stratifying for similar characteristics of the intervention and participants, could tease-out important scientific and clinically relevant information [3].

Systematic reviews are frequently recognized as the best available evidence for decisions about health-care management and policy [3–7]. Results of systematic reviews are often incorporated into clinical practice guidelines [5] and required in funding applications by granting agencies [6]. In spite of all this it appears health-care professionals and policy makers infrequently use systematic reviews to guide decision-making [8].

A limitation of many systematic reviews is that their content and format are frequently not useful to decision makers [8]. For example, while some guidance exists describing what to include in reports of systematic reviews (e.g., the PRISMA statement [9]), characteristics of the intervention that are necessary to apply their findings are infrequently provided [10–13]. This has led to some preliminary work on how to extract clinically relevant information from systematic reviews [14]. Furthermore, systematic reviews commonly show substantial heterogeneity in estimated effects (statistical heterogeneity), possibly due to methodological, clinical or unknown features in the included trials [15]. While guidance exists on the assessment and investigation of methodological [1] and statistical heterogeneity [1, 16], little attention has been given to clinical heterogeneity.

We report a systematic review of suggested methods for investigating clinical heterogeneity in systematic reviews of controlled clinical trials. We also provide some guidance for systematic reviewers.

Methods

This project identified resources giving recommendations for investigating clinical heterogeneity in systematic reviews. We extracted their recommendations, assessed their risk for bias, and categorized and described the suggestions.

Search

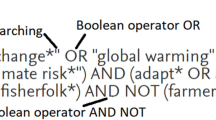

The following databases were searched: Medline (to October 29, 2010), EMBASE (to Oct 30, 2010), CINAHL (1981 to Oct 30, 2010), Health Technology Assessment (to Oct 29, 2010), the Cochrane Methodology Register (to Oct 29, 2010), and the CONSORT database of methodological papers (to October 30, 2010). A library and information scientist was consulted to create sensitive and specific searches, combining appropriate terms and extracting new terms from relevant studies for each database. The following search terms were used in the various databases and at various stages of the search: heterogeneity, applicability, clinical, assessment, checklist, guideline(s), scale, and criteria. The “adjacent” or “within X words” tools were used for the terms “clinical” and “heterogeneity” for all databases. In addition, we used the PubMed related-links option that identifies indexed studies on similar topics or having similar indexing terms to include a broad range of papers that might be indirectly related to clinical heterogeneity. Appendix A contains details of the electronic searching. One investigator (JG) contacted representatives of the Cochrane Collaboration, the Campbell Collaboration, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and a selection of experts identified through an initial review of the literature to suggest relevant articles, guidelines, position papers, textbooks or other experts in the area. We also reviewed the Cochrane Handbook, the Campbell Collaboration methods guides, and the AHRQ comparative effectiveness section for any guidance on clinical heterogeneity and searched reference lists of all retrieved resources.

The overall process consisted of a “snowballing” technique of seeking information on the topic, by which we asked experts to refer us to other experts or resources, and so on, until each new resource yielded a negligible return. Several individuals with expertise in the area of systematic reviews (JG, DM, JB, CB) met to identify key textbooks to include out of thier personal knowledge of textbooks in the area. These individuals presented what each felt were key textbooks in the area and then debated the merits of each, finally coming to a consensus-based decision on which to include. In general, these methods allowed us to include a broad array of resources related to investigating clinical heterogeneity in systematic reviews.

Inclusion criteria

Clinical heterogeneity is defined as differences in participant, treatment, or outcome characteristics or research setting. We included any methodological study, systematic review, guideline, textbook, handbook, checklist, scale, or other published guidance document with a focus on assessing, measuring, or generally investigating clinical heterogeneity between or within controlled clinical trials included in systematic reviews. This included quantitative, qualitative, graphical or tabular techniques, suggestions or methods.

Exclusion criteria

Systematic reviews of interventions for efficacy were excluded.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed and piloted independently by two individuals (JG, DM) on a random selection of 10 included resources. Extractions were checked for consensus and the form revised according to the feedback provided. One person extracted information for all included studies (JG) regarding why the authors sought to assess clinical heterogeneity; what “criteria” were used to assess clinical heterogeneity; how these were developed; the definition of clinical heterogeneity used by the authors; any graphical, tabular or other display/summary methods; statistical recommendations; reported methods used; empirical validation performed on the “criteria”; examples of implementing the methods; and recommendations on how the assessments are to be used in systematic reviews. All extractions were checked for accuracy by another individual (DM).

Synthesis methods

We thematically grouped the retrieved resources, suggestions or techniques (e.g., statistical versus qualitative recommendations), described the recommendations, highlighted any empirical support cited for each recommendation, and made an overall summary of the recommendations.

Assessment of method validation

Four individuals (JG, DM, JB, CB) met several times to discuss how to rate the variety of resources retrieved. These individuals came to a consensus that there were several classes of resources that did not have any accepted risk-of-bias assessment tools or instruments (e.g., textbooks, narrative reviews, learning guides, expert opinions). Therefore instead, of assessing “risk of bias” of these articles, we chose to determine if specific methods have been validated. Resources were considered validated if they had a clear rationale or reported empirical evidence for that recommendation (e.g., reference to previous empirical work or a test of the method with empirical or simulated data). One individual (JG) assessed the method of validation of each of these included resources.

Results

Our searches identified 2497 unique titles and abstracts; after screening, 101 papers were included in the review [17–117]. These resources included statistical papers, methodological reviews, narrative reviews, expert opinions, learning guides, consensus-based guidelines and textbooks. Figure 1 describes details of the search and screening results. The very few disagreements on inclusion were easily resolved through discussion. Sixty-four (64.6%) of the resources (statistical, methodological, consensus guideline resources) were assessed for validation. Forty-one (64.1%) of these references were evaluated as being sufficiently validated.

Table 1 describes some basic characteristics of the included resources. The most common type of resource was statistical papers (42.4%), with narrative reviews/expert opinion papers being the next most common (29.3%). Most of the papers were published in the 2000s (70.1%), and statistical methods for investigating clinical heterogeneity were the most frequent types of suggestions across resources (73.7%). Table 2 reports a list of clinical variables suggested for investigating clinical heterogeneity and the number and types of resources suggesting each. General suggestions of clinically related variables, without identification of specific clinical covariates, were the most common across all included resources. Most suggestions were within distinct categories: participant level (e.g., age), intervention level (e.g., dose), or outcome level (e.g., event type, length of follow-up) covariates. A number of resources (N = 14) reported control event rate/baseline risk as being a covariate worth investigating.

Table 3 lists recommendations regarding the process of choosing clinical characteristics to investigate. Five or more resources suggested the following: a priori choice of clinical covariates (e.g., in the review protocol); look at forest plots for trials that may contribute to heterogeneity and then look for clinical characteristics therein; proceed with investigation regardless of results of formal testing for statistical heterogeneity; base clinical covariates on a clear scientific rationale (e.g., a pathophysiological argument); investigate a small number of covariates; base each covariate suggestion on an adequate number of trials (e.g., 10 trials was a common suggestion); use caution when interpreting the findings of investigations; consider the results of such investigations as exploratory, hypothesis generating and observational; and consider confounding between covariates.

Table 4 summarizes the types of statistical methods suggested for investigating clinical heterogeneity characteristics and the number of resources suggesting each. Many included resources made some mention of statistical methods of investigating aspects of clinical heterogeneity (N = 69/99, 69.7%). Also, many of these resources made general suggestions regarding the use of subgroup analyses (N = 18) and meta-regression (N = 16); however, the majority of these did not offer any specific recommendations. A wide variety of meta-regression techniques were suggested, many of which included simulated evidence or other forms of empirical testing. Several Bayesian approaches were suggested as well as several methods for individual patient data analysis [34, 48, 58, 63, 66, 69, 71, 75, 95]. Four textbooks appeared to be relatively comprehensive in their treatment of statistical recommendations [93–95, 114].

Overall, we felt that there was some consensus across the resources regarding planning investigations, the use of clinical expertise, the rationale for choice of covariate, how to think through types of covariates, making a covariate hierarchy, post hoc covariate identification, statistical methods, data sources and interpretation of findings (See Table 5). We summarize the common recommendations that appeared in the literature to offer some preliminary guidance for systematic reviewers in Table 5 and we elaborate on several key areas in the discussion section below.

Sources appearing to be the most comprehensive in their discussion of recommendations for investigating clinical heterogeneity included the Cochrane Handbook[100] and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination’s Guidance For Undertaking Reviews In Health Care[98] and the AHRQ Comparative effectiveness review methods: clinical heterogeneity[115].

Discussion

A variety of decisions must be made when performing a systematic review. One such decision is how to deal with obvious differences among and within trials. Though a significant test for the presence of statistical heterogeneity (e.g., Q test) and a large degree of heterogeneity (e.g., I2 > 75%) might obligate a reviewer to look for covariates to explain this variability, a nonsignificant test or a small I2 (e.g., <25%) does not preclude the need to investigate covariate treatment effect interactions [35, 92, 97, 100]. That is, even with low statistical heterogeneity, there may still be factors that influence the size of the treatment effect, especially if there is a strong argument (i.e., pathophysiologic or otherwise) that some variable likely does have such an influence.

Observed or expected heterogeneity of treatment effects can be handled in several ways. The heterogeneity can be ignored and a meta-analysis conducted with a fixed-effects or random-effects model, or one can attempt to explain the heterogeneity through subgroup analyses, meta-regression or other techniques [25]. The latter moves the review away from overall statements of evidence to increasingly clinically applicable results and conclusions as well as new hypotheses for future research [75]. [Anello and Fleiss 28] make a clear distinction between meta-analyses with a goal of arriving at a common summary estimate of effect (“analytic meta-analyses”) and those focused on explaining why the effect sizes vary (“exploratory or causal meta-analyses”). The choice between these depends on the objective of the review, but it is clear that meta-analyses are more applicable to decision making (e.g., clinical, policy) when they are exploratory in nature [14, 28, 53, 75, 99]. The trials included in a systematic review may be so very similar that the summary effect estimate is the most reasonable and applicable metric [114]. But these cases are very rare, and therefore we would expect most questions asked and tested through meta-analytic methods should concern possible reasons for variation in effect [114].

Many resources were found that suggested methods for carrying out investigations of clinical heterogeneity in systematic reviews [17–102]. There was great variety in the types of resources identified (statistical papers to commentaries) and in their potential for risk of bias. It was decided early to include any resource, no matter the design, methods, or publication type. For this reason many of the included resources might normally be considered at a high risk of bias (e.g., narrative reviews, expert opinions, learning guides and commentaries) and thus providing suggestions of questionable validity. But it was felt that these types of resources might provide the most valuable information on the subject of clinical heterogeneity. That is, investigating, and in particular choosing which clinical characteristics to investigate, requires clinical expertise, or at a minimum, knowledge of empirical evidence of some covariate of importance. The inclusion of these resources could be viewed as a drawback, but we saw it as a strength of this research. It was these resources that provided most of the suggestions regarding the methods for choosing or identifying clinical covariates to investigate (Table 3). The consensus-based guidelines provided most of the suggestions regarding the process of choosing or identifying clinical covariates, and the statistical papers, as might be expected, covered the majority of the specific statistical suggestions; but the textbooks also offered many suggestions in both areas. There was some consensus across resources, but only a small number of resources included a relatively comprehensive set of recommendations [15, 93, 94, 98]. Therefore, future research should be directed at developing a comprehensive and up to date set of guidelines to aid reviewers in investigating clinical heterogeneity. We summarize the common recommendations that appear in the literature to offer some preliminary guidance for systematic reviewers (Table 5).

We were surprised to see that the term clinical heterogeneity was relatively commonly used and consistently defined. We took our definition from several publications with which we were previously familiar [1, 3]. In some of the resources the term methodological heterogeneity was used synonymously with clinical heterogeneity, or clinical heterogeneity was considered to be one component of methodological heterogeneity. While this was infrequent in the literature, methodological aspects of heterogeneity include but go beyond clinical aspects or reasons for heterogeneity between trials. Thus, when describing reasons for heterogeneity that are related to the participants, intervention, outcomes or settings of the trial, these should be termed clinical aspects of heterogeneity. A consistency of terminology is mandatory for development of thought and investigation in this area. With terminology in place, the discussion can move to our recommendations.

When planning investigations of clinical heterogeneity in systematic reviews of controlled trials one should make such plans explicit, a priori, in the protocol for the review. We would suggest that protocols be published or registered in appropriate databases [118]. Next, it is reasonable and arguably beneficial, when organizing the review team, to include clinical experts or at a minimum, state a plan for consulting clinical experts during particular phases of the review (e.g., when choosing clinical covariates or during interpretation of findings). Furthermore, a set of clinical covariates should be chosen that have a clearly stated rationale for their importance (e.g., pathophysiological argument or reference to the results of a previous large trial). Review teams should think through the following categories to determine if related covariates might logically influence the treatment effect in their particular review: participant level, intervention level, outcome level, research setting, or others unique to the research question. Several resources offered conceptual mapping, idea webbing and causal modeling as possible methods for identifying important covariates and relationships between them [98, 112, 113]. Next, a hierarchy of clinical covariates should be formed and covariates investigated only if there is sufficient rationale and later a sufficient number of trials available. That is, covariates deemed more important than others on the basis of an explicitly stated rationale should be immediately included in such investigations, with other covariates being included when the number of trials is sufficient. A generally accepted rule of thumb is that 10 events per predictor variable (EPV) maintains bias and variability at acceptable levels. This rule derives from 2 simulation studies carried out for logistic and Cox modeling strategies [119–121] and has been adapted to meta-regression [1, 114]. Therefore, it has been suggested that for each covariate there should be at least 10 trials to avoid potentially spurious findings [15]. Also, investigators should describe any plans to include additional covariates after looking at the data from included studies (e.g., forest plots). This might include an examination of summary tables or various types of plots [92, 93, 97, 98, 106], and it would be reasonable to include the clinical expert(s) at this stage to aid in the interpretation of the plotted data. Finally, how the results of any findings are going to be interpreted and used in the synthesis methods of the review needs to be explained. Most resources advise caution in interpreting these investigations, noting their exploratory nature, but when there is a clearly stated rationale, especially when derived from previous research, and sufficient trials are included, a priori planned investigations may improve applicability. Also, it was frequently suggested that the interpretation of the results of these investigations should consider confounds and important potential biases, the magnitude of the effect, confidence intervals and the directionality of the effect. Following these recommendations may lead to valid and reliable investigations of clinical heterogeneity and could improve their overall applicability and lead to future research that might test hypothesized subgroup effects.

A wide variety of statistical analyses are available for investigating clinical heterogeneity in systematic reviews of controlled clinical trials, and it is not within the scope of this paper to cover these in detail. Other resources cover this subject very well [15, 93, 95, 100, 114]. The sophistication of techniques is constantly growing, and an updated, precise summary of such methods is needed. Instead we will describe three available options frequently suggested by resources included in our review—subgroup analyses, meta-regression and the analogue to the analysis of variance (ANOVA)—and comment upon methods for exploring control group event rate.

Subgroup analyses involve separating trials into groups on the basis of some characteristic (e.g., intervention dose) and then performing separate meta-analyses for each group. This test provides an effect estimate within subgroups and a significance test for that estimate; it does not provide a test of variation in effect due to covariates. The greater the number of significant tests performed, the greater the likelihood of type 1 errors. There are some suggestions in the literature for how to control for this (e.g., Bonferroni adjustments [48]). To test for differences between subgroups a moderator analysis must be done. Moderator analyses include meta-regression and the analogue to the ANOVA, among other techniques (e.g., Z test [114]). Meta-regression is used to assess the impact of one or more independent variables (e.g., age or intervention dose) upon the dependent variable, the overall treatment effect [62]. Independent variables may be continuous or categorical, the latter expressed as a set of dummy variables with one omitted category. Several modeling strategies are available for performing meta-regression [100, 108, 122]. The results of meta-regression indicate which variables influence the summary treatment effect, how much the summary effect changes with each unit change in the variable and the p-value of this influence. It has been suggested that at least 10 trials per covariate are needed to limit spurious findings, due to the low statistical power of meta-regression, and a nonparametric test has been suggested when this tenet is not fulfilled [30] Also, one needs to consider the problems associated with ecological bias when performing meta-regressions on patient levels variables [40]. Finally, the analogue to the ANOVA examines the difference in the effect between categorical levels of some variable using identical statistical methods as a standard ANOVA [94].

The literature suggests many methods for examining the influence of the control event rate or baseline risk, which is considered an aggregate measure of known (e.g., age and disease severity) and unknown variables [15, 43, 93]. It has been argued that these examinations provide little import to clinical practice since the influence of any possible causative variables is aggregated and therefore the effect of individual covariates is unknown [15]. Also, the influence of the control event rate on the summary affect is affected by regression to the mean, and sophisticated statistical procedures are required to deal with this [15, 43, 93].

Bayesian approaches to meta-regression and hierarchical Bayes modeling, among other areas, appear to be well represented in the literature [66, 71, 95], as well as more general resources for Bayesian meta-analytic techniques [95, 123]. These methods are developing rapidly; therefore, frequent summaries of these important techniques are required as a resource to reviewers.

Finally, we would like to note suggestions in the literature concerning the utility of aggregate patient data (APD) versus individual patient data (IPD). Several resources give general recommendations regarding use of IPD when exploring characteristics that could be considered aspects of clinical heterogeneity [15, 74–76, 95, 97]. Some empirical evidence supports these recommendations [40, 66, 124, 125]. When IPD is available, it should be used as a basis to investigate aspects of clinical heterogeneity at the patient level (e.g., demographic characteristics) so as to avoid ecological bias associated with summary APD. It is reasonable to use APD for trial-level covariates (e.g., intervention characteristics) that can be considered aspects of clinical heterogeneity. In addition, there may be opportunities to strategically use APD together with IPD to avoid the significant, and sometimes insurmountable, effort required to collect complete IPD [71].

Finally, in relation to the suggestions above for including clinical expertise in systematic reviews, we feel it is the responsibility of each therapeutic discipline to create a repository of variables to consider when exploring effect variation in systematic reviews. Such warehousing of clinically important covariates would serve as an important resource, allowing systematic reviewers and clinical trialists to explore nuances in treatment effect that might inform clinical decision making, and allowing for increased applicability of findings.

Conclusions

In summary, although many recommendations are available for investigating clinical heterogeneity in systematic reviews of controlled clinical trials, there is a need to develop a comprehensive set of recommendations for how to perform valid, applicable, and appropriate investigations of clinical covariates [7, 14]. This will improve the applicability and utilization of systematic reviews by policy makers, clinicians, and other decision makers and researchers who wish to build on these findings.

Appendix A: Search strategies

1. OVID searches

Medline (1950 to Oct 29th, 2010); Cochrane Methodology Register (Oct 29th, 2010) ; HTA (Oct 29th, 2010); EMBASE (1980 to Oct 30th, 2010)“(((clinical adj5 heterogeneity)) and (assessment or checklist or guideline or guidelines or scale or criteria))”Note: A slight variation in this strategy was used for EMBASE, on the EMBASE specific search engine, for an updated search we performed from January 1st 2009 to October 30th, 2010. This was due to a change in the available electronic resources.

2. CINAHL (EBSCO) (1981 up to October 30th, 2010)

“TX clinical N8 heterogeneity and TX ( assessment OR checklist OR guideline OR guidelines OR scale OR criteria )”

3. CONSORT database of methodological papers (up to Oct 30th, 2010)

Manual search of all citations.

4. Related PubMed links for (completed on October 31st, 2010)

Thompson SG. Why sources of heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be investigated. BMJ. 1994;309:1351–5.

5. Related PubMed links for (completed on October 31st, 2010)

Higgins J, Thompson S, Deeks J, Altman D. Statistical heterogeneity in systematic reviews of clinical trials: a critical appraisal of guidelines and practice. Journal of Health Services & Research Policy. Jan 2002;7(1):51–61.

6. Related PubMed links for: (completed on October 31st, 2010)

Schmid CH, Stark PC, Berlin JA, Landais P and Lau J. Meta-regression detected associations between heterogeneous treatment effects and study-level, but not patient-level, factors. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2004;57:683–97.

References

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.0.1 [updated September 2008]. Edited by: Higgins JPT, Green S. 2008, The Cochrane Collaboration, Available from http://www.cochrane-handbook.org

Pildal J, Hrobjartsson A, Jorgensen KJ, Hilden J, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC: Impact of allocation concealment on conclusions drawn from meta-analyses of randomized trials. Int J Epidemiol. 2007, 36 (4): 847-857. 10.1093/ije/dym087.

Tugwell P, Robinson V, Grimshaw J, Santesso N: Systematic reviews and knowledge translation. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2006, 84: 643-651. 10.2471/BLT.05.026658.

Grimshaw JM, Santesso N, Cumpston M, Mayhew A, McGowan J: Knowledge for knowledge translation: the role of the cochrane collaboration. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006, 26: 55-62. 10.1002/chp.51.

British Medical Journal. 2009, Available at: http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com/ceweb/about/index.jsp. Accessed February 16, 2009

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Available at: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/193.html Accessed February 16, 2009

Cochrane Collaboration. Available at: http://cochrane.org/archives/channel_2.htm. Accessed February 16, 2009

Laupacis A, Strauss S, Systematic reviews, Systematic reviews: Time to address clinical and policy relevance as well as methodological rigor. Ann Int Med. 2007, 147 (4): 273-275.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group: Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009, 6 (&): e1000097-

Glasziou P, Meats E, Heneghan C, Shepperd S: What is missing from descriptions of treatment in trials and reviews?. BMJ. 2008, 336: 1472-1474. 10.1136/bmj.39590.732037.47.

Glasziou P, Chalmers I, Altman DG, et al: Taking healthcare interventions from trial to practice. BMJ. 2010, 341: 384-387.

Chalmers I, Glasziou P: Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet. 2009, 374: 86-89. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60329-9.

Chalmers I, Glasziou P: Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2009, 114 (6): 1341-1345. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c3020d.

Scott NA, Moga C, Barton P, Rashiq S, Schopflocher D, Taenzer P, Alberta Ambassador Program Team, et al: Creating clinically relevant knowledge from systematic reviews: The challenges of knowledge translation. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007, 13 (4): 681-688. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00830.x.

Gagnier JJ, Bombardier C, Boon H, Moher D, Beyene J: An empirical study using permutation-based resampling in meta-regression. Systematic Reviews. 2012, 1: 18-10.1186/2046-4053-1-18.

Gagnier JJ, Morgenstern H, Moher D: Recommendations for investigating clinical heterogeneity in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. 2012, Under Review

Arends LR, Hoes AW, Lubsen J, Grobbee DE, Stijnen T: Baseline risk as predictor of treatment benefit: Three clinical meta-re-analyses. Stat Med. 2000, 19: 3497-3518. 10.1002/1097-0258(20001230)19:24<3497::AID-SIM830>3.0.CO;2-H.

Higgins J, Thompson S, Deeks J, Altman D: Statistical heterogeneity in systematic reviews of clinical trials: a critical appraisal of guidelines and practice. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002, 7 (1): 51-61. 10.1258/1355819021927674.

Schmid CH, Lau J, McIntosh MW, Cappelleri JC: An empirical study of the effect of the control rate as a predictor of treatment efficacy in meta-analysis of clinical trials. Stat Med. 1998, 17 (17): 1923-1942. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19980915)17:17<1923::AID-SIM874>3.0.CO;2-6.

Thompson SG: Why sources of heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be investigated. BMJ. 1994, 309 (6965): 1351-1355. 10.1136/bmj.309.6965.1351.

van den Ende CHM, Steultjens EMJ, Bouter LM, Dekker J: Clinical heterogeneity was a common problem in Cochrane reviews of physiotherapy and occupational therapy. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006, 59: 914-919. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.12.014.

Loke YK, Price D, Herxheimer A: Systematic reviews of adverse effects: framework for a structured approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007, 7: 32-10.1186/1471-2288-7-32.

Freemantle N, Mason J, Eccles M: Deriving treatment recommendations from evidence within randomized trials. The role and limitation of meta-analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1999, 15 (2): 304-315.

Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Irvine EJ, Karlberg J: Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analyses of Helicobacter pylori infection-related clinical studies: a critical appraisal. Chin J Dig Dis. 2004, 5 (3): 126-133. 10.1111/j.1443-9573.2004.00169.x.

Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Schmid CH: Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997, 127 (9): 820-826.

Bender R, Bunce C, Clarke M, et al: Attention should be given to multiplicity issues in systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008, 61 (9): 857-865. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.03.004.

van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, Bouter L: Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine. 2003, 28 (12): 1290-1299.

Anello C, Fleiss JL: Exploratory or analytic meta-analysis: should we distinguish between them?. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995, 48 (1): 109-116. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00084-4. discussion 117-108

Simmonds MC, Higgins JP, Stewart LA, Tierney JF, Clarke MJ, Thompson SG: Meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomized trials: a review of methods used in practice. Clin Trials. 2005, 2 (3): 209-217. 10.1191/1740774505cn087oa.

Maxwell L, Santesso N, Tugwell PS, Wells GA, Judd M, Buchbinder R: Method guidelines for Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group systematic reviews. J Rheumatol. 2006, 33 (11): 2304-2311.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG: Controlling the risk of spurious findings from meta-regression. Stat Med. 2004, 23 (11): 1663-1682. 10.1002/sim.1752.

Song F, Sheldon TA, Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR: Methods for exploring heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Eval Health Prof. 2001, 24 (2): 126-151.

Glenton C, Underland V, Kho M, Pennick V, Oxman AD: Summaries of findings, descriptions of interventions, and information about adverse effects would make reviews more informative. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006, 59 (8): 770-778. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.12.011.

Dohoo I, Stryhn H, Sanchez J: Evaluation of underlying risk as a source of heterogeneity in meta-analyses: a simulation study of Bayesian and frequentist implementations of three models. Prev Vet Med. 2007, 81 (1–3): 38-55.

Hall JA, Rosenthal R: Interpreting and evaluating meta-analysis. Eval Health Prof. 1995, 18 (4): 393-407. 10.1177/016327879501800404.

Gerbarg ZB, Horwitz RI: Resolving conflicting clinical trials: guidelines for meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988, 41 (5): 503-509. 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90053-4.

DerSimonian R, Laird N: Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986, 7 (3): 177-188. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2.

St-Pierre NR: Invited review: Integrating quantitative findings from multiple studies using mixed model methodology. J Dairy Sci. 2001, 84 (4): 741-755. 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(01)74530-4.

Cook DJ, Sackett DL, Spitzer WO: Methodologic guidelines for systematic reviews of randomized control trials in health care from the Potsdam Consultation on Meta-Analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995, 48 (1): 167-171. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00172-M.

Berlin JA, Santanna J, Schmid CH, Szczech LA, Feldman HI: Individual patient- versus group-level data meta-regressions for the investigation of treatment effect modifiers: ecological bias rears its ugly head. Stat Med. 2002, 21 (3): 371-387. 10.1002/sim.1023.

Walter SD: Variation in baseline risk as an explanation of heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 1997, 16 (24): 2883-2900. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19971230)16:24<2883::AID-SIM825>3.0.CO;2-B.

Cheung MW: A model for integrating fixed-, random-, and mixed-effects meta-analyses into structural equation modeling. Psychol Methods. 2008, 13 (3): 182-202.

Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR, Sheldon TA, Song F: Systematic reviews of trials and other studies. Health Technol Assess. 1998, 2 (19): 1-276.

Rosenthal R, DiMatteo MR: Meta-analysis: recent developments in quantitative methods for literature reviews. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001, 52: 59-82. 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.59.

Song F: Exploring heterogeneity in meta-analysis: is the L'Abbe plot useful?. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999, 52 (8): 725-730. 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00066-9.

Reade MC, Delaney A, Bailey MJ, Angus DC: Bench-to-bedside review: Avoiding pitfalls in critical care meta-analysis–funnel plots, risk estimates, types of heterogeneity, baseline risk and the ecologic fallacy. Crit Care. 2008, 12 (4): 220-10.1186/cc6941.

Xu H, Platt RW, Luo ZC, Wei S, Fraser WD: Exploring heterogeneity in meta-analyses: needs, resources and challenges. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008, 22 (Suppl 1): 18-28.

Olkin I: Diagnostic statistical procedures in medical meta-analyses. Stat Med. 1999, 18 (17–18): 2331-2341.

Sterne JA, Egger M, Smith GD: Systematic reviews in health care: Investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001, 323 (7304): 101-105. 10.1136/bmj.323.7304.101.

Lipsey MW, Wilson DB: The way in which intervention studies have "personality" and why it is important to meta-analysis. Eval Health Prof. 2001, 24 (3): 236-254.

Moher D, Jadad AR, Klassen TP: Guides for reading and interpreting systematic reviews: III. How did the authors synthesize the data and make their conclusions?. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998, 152 (9): 915-920.

Schmid JE, Koch GG, LaVange LM: An overview of statistical issues and methods of meta-analysis. J Biopharm Stat. 1991, 1 (1): 103-120. 10.1080/10543409108835008.

Berlin JA: Invited commentary: benefits of heterogeneity in meta-analysis of data from epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1995, 142 (4): 383-387.

Malling HJ, Thomsen AB, Andersen JS: Heterogeneity can impair the results of Cochrane meta-analyses despite accordance with statistical guidelines. Allergy. 2008, 63 (12): 1643-1645. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01908.x.

Bravata DM, Shojania KG, Olkin I, Raveh A: CoPlot: a tool for visualizing multivariate data in medicine. Stat Med. 2008, 27 (12): 2234-2247. 10.1002/sim.3078.

Baujat B, Mahe C, Pignon JP, Hill C: A graphical method for exploring heterogeneity in meta-analyses: application to a meta-analysis of 65 trials. Stat Med. 2002, 21 (18): 2641-2652. 10.1002/sim.1221.

Higgins JP, Whitehead A: Borrowing strength from external trials in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 1996, 15 (24): 2733-2749. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19961230)15:24<2733::AID-SIM562>3.0.CO;2-0.

Michiels S, Baujat B, Mahe C, Sargent DJ, Pignon JP: Random effects survival models gave a better understanding of heterogeneity in individual patient data meta-analyses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005, 58 (3): 238-245. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.08.013.

Thompson SG, Sharp SJ: Explaining heterogeneity in meta-analysis: a comparison of methods. Stat Med. 1999, 18 (20): 2693-2708. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19991030)18:20<2693::AID-SIM235>3.0.CO;2-V.

Smith CT, Williamson PR, Marson AG: Investigating heterogeneity in an individual patient data meta-analysis of time to event outcomes. Stat Med. 2005, 24 (9): 1307-1319. 10.1002/sim.2050.

Simmonds MC, Higgins JP: Covariate heterogeneity in meta-analysis: criteria for deciding between meta-regression and individual patient data. Stat Med. 2007, 26 (15): 2982-2999. 10.1002/sim.2768.

Thompson SG, Higgins JP: How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted?. Stat Med. 2002, 21 (11): 1559-1573. 10.1002/sim.1187.

Thompson SG, Smith TC, Sharp SJ: Investigating underlying risk as a source of heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 1997, 16 (23): 2741-2758. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19971215)16:23<2741::AID-SIM703>3.0.CO;2-0.

Frost C, Clarke R, Beacon H: Use of hierarchical models for meta-analysis: experience in the metabolic ward studies of diet and blood cholesterol. Stat Med. 1999, 18 (13): 1657-1676. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19990715)18:13<1657::AID-SIM155>3.0.CO;2-M.

Naylor CD: Two cheers for meta-analysis: problems and opportunities in aggregating results of clinical trials. Cmaj. 1988, 138 (10): 891-895.

Schmid CH, Stark PC, Berlin JA, Landais P, Lau J: Meta-regression detected associations between heterogeneous treatment effects and study-level, but not patient-level, factors. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004, 57 (7): 683-697. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.12.001.

Higgins JP, Whitehead A, Turner RM, Omar RZ, Thompson SG: Meta-analysis of continuous outcome data from individual patients. Stat Med. 2001, 20 (15): 2219-2241. 10.1002/sim.918.

Berkey CS, Anderson JJ, Hoaglin DC: Multiple-outcome meta-analysis of clinical trials. Stat Med. 1996, 15 (5): 537-557. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960315)15:5<537::AID-SIM176>3.0.CO;2-S.

Thompson SG, Turner RM, Warn DE: Multilevel models for meta-analysis, and their application to absolute risk differences. Stat Methods Med Res. 2001, 10 (6): 375-392. 10.1191/096228001682157616.

Berkey CS, Hoaglin DC, Mosteller F, Colditz GA: A random-effects regression model for meta-analysis. Stat Med. 1995, 14 (4): 395-411. 10.1002/sim.4780140406.

Warn DE, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ: Bayesian random effects meta-analysis of trials with binary outcomes: methods for the absolute risk difference and relative risk scales. Stat Med. 2002, 21 (11): 1601-1623. 10.1002/sim.1189.

Nixon RM, Bansback N, Brennan A: Using mixed treatment comparisons and meta-regression to perform indirect comparisons to estimate the efficacy of biologic treatments in rheumatoid arthritis. Stat Med. 2007, 26 (6): 1237-1254. 10.1002/sim.2624.

Koopman L, van der Heijden GJ, Glasziou PP, Grobbee DE, Rovers MM: A systematic review of analytical methods used to study subgroups in (individual patient data) meta-analyses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007, 60 (10): 1002-1009.

Riley RD, Lambert PC, Staessen JA, et al: Meta-analysis of continuous outcomes combining individual patient data and aggregate data. Stat Med. 2008, 27 (11): 1870-1893. 10.1002/sim.3165.

Thompson SG, Higgins JP: Treating individuals 4: can meta-analysis help target interventions at individuals most likely to benefit?. Lancet. 2005, 365 (9456): 341-346.

Trikalinos TA, Ioannidis JP: Predictive modeling and heterogeneity of baseline risk in meta-analysis of individual patient data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001, 54 (3): 245-252. 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00311-5.

Knapp G, Hartung J: Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Stat Med. 2003, 22 (17): 2693-2710. 10.1002/sim.1482.

van Houwelingen HC, Arends LR, Stijnen T: Advanced methods in meta-analysis: multivariate approach and meta-regression. Stat Med. 2002, 21 (4): 589-624. 10.1002/sim.1040.

Sharp SJ, Thompson SG: Analysing the relationship between treatment effect and underlying risk in meta-analysis: comparison and development of approaches. Stat Med. 2000, 19 (23): 3251-3274. 10.1002/1097-0258(20001215)19:23<3251::AID-SIM625>3.0.CO;2-2.

Ghidey W, Lesaffre E, Stijnen T: Semi-parametric modelling of the distribution of the baseline risk in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2007, 26 (30): 5434-5444. 10.1002/sim.3066.

Cook RJ, Walter SD: A logistic model for trend in 2 x 2 x kappa tables with applications to meta-analyses. Biometrics. 1997, 53 (1): 352-357. 10.2307/2533120.

Chang BH, Waternaux C, Lipsitz S: Meta-analysis of binary data: which within study variance estimate to use?. Stat Med. 2001, 20 (13): 1947-1956. 10.1002/sim.823.

Davey Smith G, Egger M, Phillips AN: Meta-analysis. Beyond the grand mean?. BMJ. 1997, 315 (7122): 1610-1614. 10.1136/bmj.315.7122.1610.

Sidik K, Jonkman JN: A note on variance estimation in random effects meta-regression. J Pharm Stat. 2005, 15: 823-838.

Sutton A: Recent development in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2008, 27: 625-650. 10.1002/sim.2934.

Bagnardi V, Quatto P, Corrao G: Flexible meta-regression functions for modelling aggregate dose-response data, with an application to alcohol and mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2004, 159 (11): 1077-1086. 10.1093/aje/kwh142.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG: Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2007, 327: 557-560.

Ioannidis JP: Interpretation of test of heterogeneity and bias in meta-analysis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008, 14: 951-957. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.00986.x.

Glasziou PP, Sanders SL: Investigating causes of heterogeneity in systematic reviews. Stat Med. 2002, 21: 1503-11. 10.1002/sim.1183.

Hatala R, Wyer P, Guyatt G, for the Evidence-Based Medicine Teaching Tips Working Group: Tips for learners of evidence-based medicine: 4. Assessing heterogeneity of primary studies in systematic reviews and whether to combine their results. CMAJ. 2005, 172 (5): 661-665.

Bailey KR: Inter-study differences: How should they influence the interpretation and analysis of results?. Stat Med. 1987, 6: 351-358. 10.1002/sim.4780060327.

Khalid S, Khan RK, Kleijnen J, Antes G: Systematic Reviews to Support Evidence-based Medicine: How to Apply Findings of Health-Care Research. 2003, London: Royal Society of Medicine Press Ltd

Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Sheldon TA, Song F: Methods for Meta-analysis in Medical Research. 2000, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

Littell JC, Corcoran J, Pillai VK: Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis. 2008, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Whitehead A: Meta-Analysis of Controlled Clinical Trials. 2002, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombarider C, van Tulder M, from the Editorial Board of the Cochrane Back Review Group: 2009 Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane back review group. Spine. 2009, 34 (18): 1929-1941. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b1c99f.

National Health and Medical Research Council: How to Review the Evidence: Systematic Identification and Review of the Scientific Literature. 2000, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. 2009, York: CRD

Oxman AD, Guyatt GH: A consumer's guide to subgroup analyses. Ann Intern Med. 1992, 116 (1): 78-84.

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.0.0 [updated September 2008]. Edited by: Higgins JPT, Green S. 2008, The Cochrane Collaboration, Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org

Imperiale TF: Meta-analysis: when and how. Hepatology. 1999, 29 (6 Suppl): 26S-31S.

Shekelle PG, Morton SC: Principles of metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 2000, 27 (1): 251-252. discussion 252-53

Nagin DS, Odgers CL: Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annu Rev Clin Pscyhol. 2010, 6: 109-138. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131413.

Virgile G, Conto AA, Moja L, Gensini GL, Gusinu R: Heterogeneity and meta-analyses: do study results truly differ?. Intern Emerg Med. 2009, 4: 423-427. 10.1007/s11739-009-0296-6.

Skipka G, Bender R: Intervention effects in the case of heterogeneity between three subgroups: Assessment within the framework of systematic reviews. Methods Inf Med. 2010, 49: 613-617. 10.3414/ME09-02-0054.

Groenwold RHH, Rovers MM, Lubsen J, van der Heijden JMG: Subgroup effects despite homogenous heterogeneity test results. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2010, 10: 43-10.1186/1471-2288-10-43.

Lockwood CM, DeFrancesco CA, Elliot DL, Beresford SAA, Toobert DJ: Mediation analyses: Applications in nutrition research and reading the literature. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010, 110: 753-763. 10.1016/j.jada.2010.02.005.

Baker W, White M, Cappelleri JC, Kluger J, Colman CI: Understanding heterogeneity in meta-analysis: the role of meta-regression. Int J Clin Pract. 2009, 63 (10): 1426-1434. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02168.x.

Jones AP, Riley RD, Williamson PR, Whitehead A: Meta-analysis of individual patient data versus aggregate data from longitudinal clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2009, 6: 16-27. 10.1177/1740774508100984.

Hemming K, Hutton JL, Maguire MJ, Marson AG: Meta-regression with partial information on summary trial or patient characteristics. Stat Med. 2008, 29: 1312-1324.

Salanti G, Marinho V, Higgins JPT: A case study of multiple-treatments meta-analysis demonstrates covariates should be considered. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009, 62: 857-864. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.001.

Glasziou P, Chalmers I, Altman DG, Bastian H, Boutron I, Brice A, et al: Taking healthcare interventions from trial to practice. BMJ. 2010, 341: c3852-10.1136/bmj.c3852.

Shadish WR: Meta-analysis and the exploration of causal mediating processes: A primer of examples, methods, and issues. Psychol Methods. 1996, 1: 47-65.

Borenstein MA, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR: Introduction to Meta-Analysis. 2009, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons

West SL, Gartlehner G, Mansfield AJ, et al: Comparative effectiveness review methods: clinical heterogeneity. Posted 09/28/2010, Rockville, MD, Available at http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/

McIntosh MW: The population risk as an explanatory variable in research synthesis of clinical trials. Stats Med. 1996, 15: 1713-1728. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960830)15:16<1713::AID-SIM331>3.0.CO;2-D.

Boutitie F, Gueyffier F, Pocock SJ, Biossel JP: Assessing treatment-time interaction in clinical trials with time to event data: A meta-analysis of hypertension trials. Stat Med. 1998, 17: 2883-2903. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19981230)17:24<2883::AID-SIM900>3.0.CO;2-L.

Booth A, Clarke M, Ghersi D, MOher D, Petticrew M, Stewart L: An international registry of systematic-review protocols. Lancet. 2011, 377 (9760): 108-109. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60903-8.

Concato J, Peduzzi P, Holfold TR, et al: Importance of events per independent variable in proportional hazards analysis. I. Background, goals, and general strategy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995, 48: 1495-1501. 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00510-2.

Peduzzi P, Concato J, Feinstein AR, et al: Importance of events per independent variable in proportional hazards regression analysis. II. Accuracy and precision of regression estimates. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995, 48: 1503-1510. 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00048-8.

Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, et al: A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996, 49: 1373-1379. 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00236-3.

Harrell FE: Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. 2001, New York: Springer

Spiegelhalter DJ, Myles JP, Jones DR, Abrams KR: Bayesian methods in health technology assessment: A review. Health Technol Assess. 2000, 4: 1-130.

Smith CT, Williamson PR, Marson AG: An overview of methods and empirical comparison of aggregate data and individual patient data results for investigating heterogeneity in meta-analysis to time-to-event data. J Eval Clin Pract. 2002, 55: 86-94.

Lambert PC, Sutton AJ, Jones ADR: A comparison of patient-level covariates in meta-regression with individual patient data meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002, 55: 86-94. 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00414-0.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/12/111/prepub

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JG developed conceptualized the project, searched for the literature, extracted data, and wrote the manuscript. DM, HB, JB and CB conceptualized the project and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Gagnier, J.J., Moher, D., Boon, H. et al. Investigating clinical heterogeneity in systematic reviews: a methodologic review of guidance in the literature. BMC Med Res Methodol 12, 111 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-111

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-111