Abstract

Background

A number of previous studies have suggested that overweight or obese patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) may have lower morbidity and mortality than their leaner counterparts. Few studies have addressed possible gender differences, and the results are conflicting. We examined the association between body mass index (BMI) and risk of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), cardiovascular (CV) death and all-cause mortality in men and women with suspected stable angina pectoris.

Method

The cohort included 4164 patients with suspected stable angina undergoing elective coronary angiography between 2000 and 2004. Events were registered until the end of 2006. Hazard ratios (HR) (95% confidence intervals) were estimated using Cox regression by comparing normal weight (18.5-24.9 kg/m2) with overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) and obese (≥30 kg/m2) patients. Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) patients were excluded from the study.

Results

Of 4131 patients with complete data, 72% were males and 75% were diagnosed with significant CAD. The mean (standard deviation (SD)) age in the total population was 62 (10) years. Mean (SD) BMI was 26.8 (3.9) kg/m2, 34% was normal weight, 48% overweight and 19% obese. During follow up, a total of 337 (8.2%) experienced an AMI and 302 (7.3%) patients died, of whom 165 (4.0%) died from cardiovascular causes. We observed a significant interaction between BMI groups and gender with regards to risk of AMI (p = 0.011) and CV death (p = 0.031), but not to risk of all-cause mortality; obese men had a multivariate adjusted increased risk of AMI (HR 1.80 (1.28, 2.52)) and CV death (HR 1.60 (1.00, 2.55)) compared to normal weight men. By contrast, overweight women had a decreased risk of AMI (HR 0.56 (0.33, 0.98)) compared to normal weight women. The risk of all-cause mortality did not differ between BMI categories.

Conclusion

Compared with normal weight subjects, obese men had an increased risk of AMI and CV death, while overweight women had a decreased risk of AMI. These findings may potentially explain some of the result variation in previous studies reporting on the obesity paradox.

Trial registration

Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00354081

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death globally: the majority dying from ischemic heart disease [1]. Overweight and obesity, most commonly defined according to body mass index (BMI), has been characterized as a major modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality by the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology [2].

As recently reviewed, some studies of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) suggest that being overweight or obese has beneficial effects in terms of reduced risk of CV events and/or mortality; a phenomenon known as the obesity paradox. However, there is no broad consensus regarding the obesity paradox, as several studies are unsupportive of this conclusion [3].

Moreover, despite the fact that both body fat percentage and distribution vary by gender [4], only a limited number of studies among patients with CAD or suspected CAD have examined the association between BMI and risk of coronary events and mortality in men and women separately, and the reported results are conflicting [5–9]. There is, however, a tendency towards a non-disadvantageous [5, 6, 9] or even a beneficial [7] effect of overweight and obesity among women, while obesity appears to increase the risk of coronary events in men [5, 6].

In the present study we examined the association between BMI and risk of incident acute myocardial infarction (AMI), CV death and all-cause mortality in a large population of men and women with suspected CAD. We hypothesized that overweight and/or obesity, as compared to normal weight, was associated with an increased risk of AMI, CV death and all-cause mortality among men, but not among women.

Methods

Study design and patient population

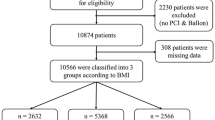

The patients recruited for the present investigation are described in detail elsewhere [10]. In brief, 4164 patients undergoing elective coronary angiography for suspected stable angina pectoris were recruited from two university hospitals in Western Norway from January 2000 to April 2004. Of these patients, 2573 (62.0%) were enrolled in the Western Norway B Vitamin Intervention Trial (WENBIT) which studied the prognostic impact of B-vitamin supplementation upon incident CV events and mortality (clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00354081) [11]. Patients for whom there was no BMI data (n = 3) were excluded from the study, as were underweight patients (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) (n = 30).This left a total of 4131 subjects eligible for the analyses.

The study protocol met the mandate of the Helsinki Declaration, and was approved by the Western Norway Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics and the Norwegian Data Inspectorate. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Baseline data and biochemical analyses

Height, weight and blood pressure were measured at baseline by trained study personnel. BMI was calculated by dividing weight by height squared (kg/m2). Each patient provided information about medical history, risk factors and medications through a self-administered questionnaire, and all information was subsequently validated against medical records. Diabetes mellitus included type 1 and 2. Current smokers included those with self-reported current smoking, those who had quit smoking within <1 month and those with plasma cotinine >85 ng/mL [12]. Patients, who reported to have quit smoking > 1 month prior to inclusion and had plasma cotinine levels ≤85 ng/mL, were categorized as ex-smokers. Pulmonary disease included chronic obstructive lung disease, other chronic lung diseases and pulmonal hypertension. Cancer included active cancer with or without metastases. Family history of early coronary heart disease (CHD) encompassed those reporting to have at least one 1st degree relative suffering from CHD before the age of 55 for men and 65 for women. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was determined by ventriculography or echocardiography. The extent of CAD at angiography was scored as 0–3 as has previously been described [11]. Baseline coronary revascularisation procedures, after baseline angiography, included percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG).

Blood samples were collected by study personnel prior to angiography and stored at -80˚C until analysis. Serum apolipoprotein A-1 (ApoA1), apolipoprotein B (ApoB) and lipoprotein (a) (Lp(a)) were analysed on the Hitachi 917 system (Roche Diagnostics, GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Serum C-reactive protein (CRP) was measured using a latex, high sensitive assay (Behring Diagnostics, Marburg, Germany). Plasma cotinine was measured by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry [13]. Low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was calculated using the Friedewald formula [14] and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was estimated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula [15].

Follow-up and end points

The study participants were followed from angiography until they experienced one of the primary endpoints; AMI (fatal or non-fatal), death or till December 31st 2006.

Information on clinical events was collected from The Western Norway Cardiovascular Registry and from the Cause of Death Registry at Statistics Norway as previously described [11]. An event was classified as fatal if death occurred within 28 days after onset. AMI was classified according to the diagnostic criteria of the revised AMI definition published in 2000 [16], and fatal strokes were classified according to diagnostic criteria published in 2001 [17]. Procedure-related non-fatal AMI occurring within 24 h of coronary angiography, PCI or CABG were not included in the end-point. CV death included causes of death coded I00-I99 or R96, according to the International Statistical Evaluation of Disease, Tenth Revision system. An endpoints committee adjudicated all events.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as means (standard deviation (SD)). Categorical variables are reported as counts (percentage). Non-normally distributed variables (diastolic blood pressure, serum creatinine, CRP, plasma glucose, serum triglycerides and Lp(a)) were log transformed. BMI groups were created using established BMI cut-offs; Normal weight (BMI 18.5-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2) and obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2). Underweight patients (n = 30) were eliminated due to the possibility of reverse causation. Between group differences were tested by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or independent samples t-test for continuous variables, and by chi square test for categorical variables. Post hoc tests were applied for multiple comparisons where appropriate.

The relationships between baseline BMI and subsequent risk of AMI, CV death and all-cause mortality were evaluated across BMI groups. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of endpoints associated with BMI categories were estimated with Cox proportional hazard models using the BMI normal weight category as reference. The time, in days, from angiography until endpoint (AMI, CV death and all-cause mortality) or end of study (December 31st 2006) was used as time scale. Proportionality assumptions were tested by visual examination of log minus log plots and calculating Schoenfeld residuals. Covariates in the multivariate adjusted models were selected based on clinical relevance and the change-in-estimate method [18], with a limit for inclusion of 10% change in the risk ratio. The final multivariate model included gender, age (continuous), LVEF (%), current smoking (yes/no), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) -inhibitors (yes/no), loop diuretics (yes/no) and pulmonary disease (yes/no). Further adjustment of the multivariate Cox model did not alter the results in the total population or in gender stratified analyses; systolic and diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), diabetes mellitus (yes/no), previous AMI (yes/no), extent of significant CAD (0–3), serum creatinine levels (μmol/L), CRP (mg/L), total cholesterol (mmol/L), vitamin B6 (yes/no) or folate/B12 (yes/no) intervention status (data not shown).

Effect modifications by gender were investigated by including the product of gender and BMI categories as an interaction term in the multivariate adjusted Cox model.

All tests were 2-sided, and a p-value <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 17 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) and R 2.14.2 (The R-Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Baseline characteristics

The cohort consisted of 4131 patients (72% males), and the mean (SD) age in the total population was 62 (10) years. Baseline characteristics across BMI groups are presented in Table 1. The mean (SD) BMI was 26.8 (3.9) kg/m2, and 34% of the patients had a BMI within the normal weight range, 48% were overweight and 19% were obese.

Compared to the overweight and obese groups, the normal weight group was characterised by older age and a higher proportion of current smokers and subjects with a history of peripheral arterial disease. Mean blood pressure was lower in this group, as was the prevalence of diabetes. The extent of CAD at baseline did, however, not differ between the BMI categories. Compared to normal weight patients, overweight and obese patients were more often discharged with aspirin, statins and beta-blockers, while ACE inhibitors and loop diuretics were more often prescribed to obese patients.

The levels of eGFR, serum CRP, plasma glucose, HbA1c, Hb, serum ApoB, triglyceride and Lp(a) increased across incremental BMI groups, while serum ApoA1 and HDL cholesterol levels declined.

Baseline characteristics according to gender

Among men, 32% were normal weight, 51% overweight and 17% obese, whereas the respective proportions were 38%, 40% and 22% among women. Mean (SD) BMI was 26.8 (3.7) kg/m2 among men and 26.8 (4.7) kg/m2 among women.

Baseline characteristics according to gender and BMI groups are presented in Table 2. Compared to women, men were generally younger, and there was an inverse relationship between age and BMI among men. Men had worse CV risk profile and more severe CAD, at baseline, than women. Correspondingly, men, compared to women, did more often undergo revascularisation procedures following baseline angiography and were more often discharged with medication.

Follow-up and end-points

During the follow-up period (mean (SD) 4.8 (1.4) years), 337 (8.2%) patients experienced an AMI, of which 101 (30%) were fatal. A total of 302 (7.3%) patients died, of whom 165 (55%) died from cardiovascular causes.

There were statistically significant multivariate adjusted interactions between gender and BMI categories with regards to risk of incident AMI (p-int = 0.011) and CV-death (p-int = 0.031), but not to all-cause mortality (p-int = 0.427).

A total of 115 (8.2%) normal weight patients, 127 (6.4%) overweight patients and 60 (7.8%) obese patients died. The risk of all-cause mortality did not differ significantly between BMI categories in any analyses; compared to the normal weight group, the multivariate adjusted HR (95% CI) was 0.95 (0.74, 1.23) in the overweight group and 1.16 (0.84, 1.60) in the obese group.

Analyses were repeated in subgroups of patients with significant CAD or without diabetes only, and the results were not significantly different from those reported (data not shown).

Gender stratified analyses

A total of 267 (8.9%) men and 70 (6.1%) women suffered an AMI. Further, 241 (8.1%) men and 61 (5.3%) women died, whereof 132 (55%) male deaths and 33 (54%) female deaths were characterised as CV deaths.

Obese men had a significantly higher multivariate adjusted risk of both incident AMI; HR 1.80 (1.28, 2.52), and CV death; HR 1.60 (1.00, 2.55), compared to normal weight men (Table 3).

Overweight women had a significantly lower multivariate adjusted risk of AMI; HR 0.56 (0.33, 0.98), compared to normal weight women (Table 4). By contrast, the multivariate adjusted HR for AMI between normal weight women and obese women did not differ significantly.

Discussion

Principal findings

In this large longitudinal prospective cohort study of more than 4000 patients with suspected stable angina pectoris, we demonstrate that obese male patients had a 1.8 fold and 1.6 fold increased risk of incident AMI and CV death compared to normal weight men. By contrast, compared to normal weight women, obese women had similar risk of AMI and CV death, while overweight women had nearly half the risk of incident AMI. The risk of all-cause mortality associated with BMI was similar among men and women, and did not differ significantly across BMI categories.

BMI and risk of AMI, CV death and all-cause mortality in men and women

Strong associations between overweight/obesity and risk of CVD and death have been demonstrated in the general population [19, 20]. By contrast, several studies of patients with CAD have demonstrated that overweight and/or obese patients may have a better morbidity and mortality prognosis than their leaner counterparts; although as one recent review points out, this observation is not supported by all [3].

Only a few studies of patients with CAD have examined the association between BMI and risk of CV events and mortality in men and women separately. Our finding of an increased risk of cardiovascular events among obese men are in accordance with the results from a previous US study of patients with stable CVD, whereof 85% had CHD, as well as with a multi-ethnic sample study of patients with established CAD [5, 6]. However, while these studies did not observe any significant associations between BMI and risk of major adverse coronary events in women, we report a nearly halved adjusted risk of AMI among overweight women as compared to their normal weight counterparts.

In the present study, there was no interaction between BMI and gender with regards to all-cause mortality. Moreover, the risk of death did not differ between BMI groups. These findings are in accordance with a previous study conducted among European patients with CAD [21]. To the best of our knowledge only two studies, of patients with CAD, have examined the association between BMI and all-cause mortality in men and women separately [7, 8]. First, a study of Danish patients with AMI showed that normal weight, overweight and obese men had similar risk of death, whereas overweight women had a slightly decreased risk (HR (95% CI); 0.78 (0.68, 0.90)) of death, as compared to their normal weight counterparts. Furthermore, in a follow up study of the CADILLAC trial, they observed significantly lower in-hospital mortality (0.9% vs. 2.7%), 30 days (1.1% vs. 3.8%) and 1- year (1.8% vs. 7.5%) mortality in obese patients with AMI undergoing PCI when compared to normal weight patients. Statistical significance was, however, only reached in males.

Possible explanations

BMI is often used to quantify overweight and obesity owing to a high fat percentage correlation, but does not account for fat distribution. Men have a tendency to store excessive fat in visceral fat deposits, whereas women usually store fat in peripheral subcutaneous distributions [4]. Excessive visceral fat is associated with an increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome, putting men at a greater risk of developing CVD, while subcutaneous fat in the femoral-gluteal region may be associated with a more favourable CV risk profile [22]. Furthermore, overweight and obese postmenopausal women may benefit from the increase in circulating levels of estrogen produced by the adipose tissue [23, 24].

Moreover, at baseline, men were more often affected by CV risk factors and had more severe CAD. Inclusion of these potential confounding variables in stratified multivariate analyses did not alter our results. Differing health status at baseline is thus unlikely to be the cause of the observed gender interaction.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The main strength of the present study is its, well defined population with complete follow up of clinical endpoints. Limitations include the single baseline measurements of BMI and other time dependent cofactors such as medication. We did not have sufficient data on possible confounders such as physical activity, socioeconomic status or cardio- respiratory fitness and intentional vs. unintentional weight loss, and thus we cannot exclude the possibility that residual confounding from unmeasured causal factors unevenly distributed between BMI groups may have influenced our results. Unfortunately, we did not have data on recent weight loss prior to inclusion, but as underweight patients (BMI <18.5 kg/m2) were excluded, and adjustment for possible confounders such as cancer, pulmonary disease, extent of significant CAD and LVEF did not significantly alter our results, reverse causation is unlikely. BMI was positively associated with common obesity related characteristics such as higher blood pressure, diabetes, an unfavourable lipid profile, higher eGFR and CRP. Adjustment for these variables did not have a significant effect on our results, but we would in any case not include these variables in a final multivariate adjusted survival model because of the possibility of over-adjustment bias. We did, however, adjust for use of ACE inhibitors and loop diuretics as a proxy of heart failure, and there is the possibility that these variables may have mediated some of the effect of BMI.

It has previously been suggested that BMI is an inadequate marker of overweight and obesity in patients with CAD [25], with waist circumference or waist to hip ratio suggested as better predictors of cardiovascular events, especially in women [6, 26]. Studies supporting an obesity paradox have almost exclusively used BMI as an index of obesity [3]. We thus suspect that the diverging findings among such studies may be the result of BMI’s inadequacy as a quantifier of true body fatness and fat distribution.

Given that there were relatively few females in the study population and the event rate was low, we thus had a low statistical power to by which to detect the possible effects of BMI on risk of events among women. Further, we cannot rule out that the relatively lower incidence rate of AMI among women is a result of detection bias; women, compared to men, are more likely to experience atypical symptoms of AMI and may consequently delay seeking medical care for symptoms or be misdiagnosed by healthcare providers [27]. Finally, the inclusion of predominantly white subjects limits the ability to generalise our findings to non-white populations.

Conclusion

Among 4131 men and women with suspected stable angina pectoris, obese men carried an 80% and 60% higher risk of AMI and CV death, respectively, compared to normal weight men, whereas being overweight, compared to normal weight, was associated with a 50% lower risk of AMI among women. These findings may potentially explain some of the result variation in studies reporting on the obesity paradox, with further investigation of the interaction between gender and BMI in terms of risk of CV events and mortality therefore warranted.

References

The top 10 causes of death. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/,

Goff DC, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, Coady S, D'Agostino RB, Gibbons R, Greenland P, Lackland DT, Levy D, O'Donnell CJ, Robinson J, Schwartz JS, Shero ST, Smith SC, Sorlie P, Stone NJ, Wilson PWF: 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013

Chrysant SG, Chrysant GS: New insights into the true nature of the obesity paradox and the lower cardiovascular risk. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2013, 7 (1): 85-94. 10.1016/j.jash.2012.11.008.

Lemieux S, Prud'homme D, Bouchard C, Tremblay A, Despres JP: Sex differences in the relation of visceral adipose tissue accumulation to total body fatness. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993, 58 (4): 463-467.

Domanski MJ, Jablonski KA, Rice MM, Fowler SE, Braunwald E, Investigators P: Obesity and cardiovascular events in patients with established coronary disease. Eur Heart J. 2006, 27 (12): 1416-1422.

Dagenais GR, Yi Q, Mann JF, Bosch J, Pogue J, Yusuf S: Prognostic impact of body weight and abdominal obesity in women and men with cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2005, 149 (1): 54-60. 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.07.009.

Kragelund C, Hassager C, Hildebrandt P, Torp-Pedersen C, Kober L: Impact of obesity on long-term prognosis following acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2005, 98 (1): 123-131. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.03.042.

Nikolsky E, Stone GW, Grines CL, Cox DA, Garcia E, Tcheng JE, Griffin JJ, Guagliumi G, Stuckey T, Turco M, Negoita M, Lansky AJ, Mehran R: Impact of body mass index on outcomes after primary angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2006, 151 (1): 168-175. 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.024.

Wessel TR, Arant CB, Olson MB, Johnson BD, Reis SE, Sharaf BL, Shaw LJ, Handberg E, Sopko G, Kelsey SF, Pepine CJ, Merz NB: Relationship of physical fitness vs body mass index with coronary artery disease and cardiovascular events in women. JAMA. 2004, 292 (10): 1179-1187. 10.1001/jama.292.10.1179.

Svingen GF, Ueland PM, Pedersen EK, Schartum-Hansen H, Seifert R, Ebbing M, Loland KH, Tell GS, Nygard O: Plasma dimethylglycine and risk of incident acute myocardial infarction in patients with stable angina pectoris. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013

Ebbing M, Bleie O, Ueland PM, Nordrehaug JE, Nilsen DW, Vollset SE, Refsum H, Pedersen EK, Nygard O: Mortality and cardiovascular events in patients treated with homocysteine-lowering B vitamins after coronary angiography: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008, 300 (7): 795-804. 10.1001/jama.300.7.795.

Benowitz NL, Jacob P, Ahijevych K, Jarvis MJ, Hall S, LeHouezec J, Hansson A, Henningfield J, Tsoh J, Hurt RD, Velicer W for the The SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification: Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002, 4 (2): 149-159. 10.1080/14622200210123581.

Midttun O, Hustad S, Ueland PM: Quantitative profiling of biomarkers related to B-vitamin status, tryptophan metabolism and inflammation in human plasma by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2009, 23 (9): 1371-1379. 10.1002/rcm.4013.

Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS: Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972, 18 (6): 499-502.

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J: A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009, 150 (9): 604-612. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006.

Alpert JS, Antman E, Apple F, Beller G, Breithardt G, Armstrong PW, Bassand JP, Baye´s de Luna A, Chaitman BR, Clemmensen P, Falk E, Fishbein MC, Galvani M, Garson A, Grines C, Hamm C, Hoppe U, Jaffe A, Katus H, Kjekshus J, Klein W, Klootwijk P, Lenfant C, Levy D, Levy RI, Luepker R, Marcus F, Näslund U, Ohman M, Pahlm O, et al: Myocardial infarction redefined--a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2000, 21 (18): 1502-1513.

Cannon CP, Battler A, Brindis RG, Cox JL, Ellis SG, Every NR, Flaherty JT, Harrington RA, Krumholz HM, Simoons ML, Van De Werf FJJ, Weintraub WS, Mitchell KR, Morrisson SL, Anderson HV, Cannom DS, Chitwood WR, Cigarroa JE, Collins-Nakai RL, Gibbons RJ, Grover FL, Heidenreich PA, Khandheria BK, Knoebel SB, Krumholz HL, Malenka DJ, Mark DB, Mckay CR, Passamani ER, Radford MJ, et al: American College of Cardiology key data elements and definitions for measuring the clinical management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes. A report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Acute Coronary Syndromes Writing Committee). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001, 38 (7): 2114-2130. 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01702-8.

Greenland S: Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. Am J Public Health. 1989, 79 (3): 340-349. 10.2105/AJPH.79.3.340.

Grundy SM, Pasternak R, Greenland P, Smith S, Fuster V: Assessment of cardiovascular risk by use of multiple-risk-factor assessment equations: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. Circulation. 1999, 100 (13): 1481-1492. 10.1161/01.CIR.100.13.1481.

Eckel RH: Obesity and heart disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee. Am Heart Assoc Circul. 1997, 96 (9): 3248-3250.

De Bacquer D, De Backer G, Ostor E, Simon J, Pyorala K, Group EIS: Predictive value of classical risk factors and their control in coronary patients: a follow-up of the EUROASPIRE I cohort. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2003, 10 (4): 289-295. 10.1097/00149831-200308000-00012.

Snijder MB, van Dam RM, Visser M, Seidell JC: What aspects of body fat are particularly hazardous and how do we measure them?. Int J Epidemiol. 2006, 35 (1): 83-92.

Silva TC, Barrett-Connor E, Ramires JA, Mansur AP: Obesity, estrone, and coronary artery disease in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2008, 59 (3): 242-248. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.01.008.

Castracane VD, Kraemer GR, Ogden BW, Kraemer RR: Interrelationships of serum estradiol, estrone, and estrone sulfate, adiposity, biochemical bone markers, and leptin in post-menopausal women. Maturitas. 2006, 53 (2): 217-225. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.04.007.

Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, Jensen MD, Thomas RJ, Squires RW, Allison TG, Korinek J, Lopez-Jimenez F: Diagnostic performance of body mass index to detect obesity in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2007, 28 (17): 2087-2093. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm243.

Rexrode KM, Carey VJ, Hennekens CH, Walters EE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Manson JE: Abdominal adiposity and coronary heart disease in women. JAMA. 1998, 280 (21): 1843-1848. 10.1001/jama.280.21.1843.

Maas AH, van der Schouw YT, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Swahn E, Appelman YE, Pasterkamp G, Ten Cate H, Nilsson PM, Huisman MV, Stam HC, Eizema K, Stramba-Badiale M: Red alert for women's heart: the urgent need for more research and knowledge on cardiovascular disease in women: proceedings of the workshop held in Brussels on gender differences in cardiovascular disease, 29 September 2010. Eur Heart J. 2011, 32 (11): 1362-1368. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr048.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2261/14/68/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank all WENBIT coworkers at Haukeland and Stavanger University Hospitals, Norway, as well as the Endpoints Committee: Marta Ebbing (HUS), Leik Woie (SUS), Eva Ringdal Pedersen (UiB), Hall Schartum-Hansen (UiB), Per Lund Johansen (UiB) (Chair). We would also like to thank all those who participated in the study for their time and effort. Thanks are also due to Matthew McGee for proofreading the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ON conceived of the study and contributed to the study design; GFTS, EKRP, HSH and ON conducted research; HB, RS analyzed data or performed statistical analysis; HB, JKH, GFTS, JH and ON wrote the paper; HB had primary responsibility for final content; HB, JKH, JH and ON interpreted data; HB, JKH, GFTS, EKRP, HSH, JH and ON critically revised the manuscript. All listed authors take responsibility for all aspects of the reliability and freedom from bias of the data presented and their discussed interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Jøran Hjelmesæth and Ottar Nygård contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Borgeraas, H., Hertel, J.K., Svingen, G.F.T. et al. Association of body mass index with risk of acute myocardial infarction and mortality in Norwegian male and female patients with suspected stable angina pectoris: a prospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 14, 68 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-14-68

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-14-68