Abstract

Background

Ethnic differences in clinical outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) have been reported. Data within different Asian subpopulations is scarce. We aim to explore the differences in clinical profile and outcome between Chinese, Malay and Indian Asian patients who undergo PCI for coronary artery disease (CAD).

Methods

A prospective registry of consecutive patients undergoing PCI from January 2002 to December 2007 at a tertiary care center was analyzed. Primary endpoint was major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) of myocardial infarction (MI), repeat revascularization and all-cause death at six months.

Results

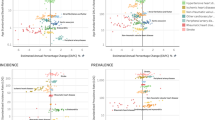

7889 patients underwent PCI; 7544 (96%) patients completed follow-up and were included in the analysis (79% males with mean age of 59 years ± 11). There were 5130 (68%) Chinese, 1056 (14%) Malays and 1001 (13.3%) Indian patients. The remaining 357 (4.7%) patients from other minority ethnic groups were excluded from the analysis. The primary end-point occurred in 684 (9.1%) patients at six months. Indians had the highest rates of six month MACE compared to Chinese and Malays (Indians 12% vs. Chinese 8.2% vs. Malays 10.7%; OR 1.55 95%CI 1.24-1.93, p < 0.001). This was contributed by increased rates of MI (Indians 1.9% vs. Chinese 0.9% vs. Malays 1.3%; OR 4.49 95%CI 1.91-10.56 p = 0.001), repeat revascularization (Indians 6.5% vs. Chinese 4.1% vs. Malays 5.1%; OR 1.64 95%CI 1.22-2.21 p = 0.0012) and death (Indians 11.4% vs. Chinese 7.6% vs. Malays 9.9%; OR 1.65 95%CI 1.23-2.20 p = 0.001) amongst Indian patients.

Conclusion

These data indicate that ethnic variations in clinical outcome exist following PCI. In particular, Indian patients have higher six month event rates compared to Chinese and Malays. Future studies are warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms behind these variations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The widespread utilization of PCI as a treatment strategy for coronary artery disease has altered the management of patients with CAD [1, 2]. Several reports have examined the outcomes following PCI of various patient populations [3–9]. While population registries a decade ago have shown differences in coronary mortality following an acute myocardial infarction (MI) among various ethnic groups, contemporary reports of differences in clinical outcomes following PCI among Asians remain limited [10–13].

The objective of this study was to examine, in a contemporary group of patients from various Asian subpopulations in a similar social environment, the impact of ethnic differences on clinical outcome after PCI for CAD.

Methods

Design and study population

We designed a prospective registry of all consecutive patients who were referred for PCI between January 2002 and December 2007, including both emergency as well as elective PCI procedures. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from our local institutional review board and patient consent obtained where appropriate.

The ethnic group of the patient was obtained from the source of notification, based on the national census classification. We included the three major ethnic groups comprising of Chinese, Malays and Indians, and excluded the other remaining minority groups from the analysis.

Baseline clinical characteristics were collected during the procedure. Follow-up data was obtained from medical records or telephone follow-up. The primary endpoint of this analysis was major adverse cardiac event (MACE) rates defined as nonfatal MI, repeat revascularization and all-cause death at six months post-index PCI. Secondary endpoints were one month MACE, and individual MACE components at one month and six months.

If a patient underwent more than one PCI during this time frame, the initial one was taken as the index procedure.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented as percentages and compared using chi-square/Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation and comparisons were made by means of analysis of variance. Univariate analysis was performed to compare demographic and baseline characteristics among the ethnic groups. Stepwise multivariate logistic regressions were carried out to assess the association between one- and six-months adverse events for Malay and Indian patients as compared to Chinese patients with correction for significant differences in baseline diabetes, family history of CAD, tobacco smoking and primary PCI (Table 1). Statistical significance was assumed if p < 0.05.

Data management and analysis were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, (SPSS, Chicago Inc.) Windows version 16.

Results

A total of 7889 consecutive patients who underwent PCI between January 2002 and December 2007 were enrolled in our registry, and 7544 (96%) patients who completed follow-up were included in this present analysis. In this patient group (n = 7544), 68% (n = 5130) were Chinese, 14% (n = 1056) were Malay, 13.3% (n = 1001) were Indian, and 4.7% (n = 357) were patients from other minority ethnic groups.

Compared with Chinese patients, there was a higher incidence of diabetes mellitus, family history of CAD and history of tobacco smoking among Indian and Malay patients (Table 1). Apart from a higher incidence of primary PCI for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction among Indians, the clinical indications for referral for PCI were similar among the ethnic groups. Bare metal stents were used in 56% of the entire cohort while drug-eluting stents were used in the remaining 44%; there were no differences in the type of stent used among the difference ethnic groups. Compliance to dual antiplatelet therapy from time of PCI to hospital discharge was satisfactory; 93.5% of patients were discharged with Aspirin while 93.9% of patients were discharged with clopidogrel.

Comparison of the primary endpoint of any major adverse cardiovascular event between ethnic groups is shown in Table 2.

At six months, the primary endpoint occurred more frequently among Indian and Malay patients than Chinese patients [12% vs. 10.7% vs. 8.2% respectively at six months (p < 0.001)]. Compared to Chinese patients, Malays also had a higher likelihood of repeat revascularization (OR 1.35 95%CI 1.08-1.69, p = 0.009) and MACE at six months (OR1.36 95%CI 1.09-1.69, p = 0.006) (Figure 1 and Table 2). Indian patients had higher risks of mortality (OR1.65 95%CI1.23-2.20 p = 0.001) (Figure 2) and required more revascularization procedures (OR1.59 95%CI 1.27 1.98 p < 0.001) compared to the Chinese (Figure 1).

One-month outcomes were significantly worse among Indian patients compared to Chinese patients. Indians and Malays were more likely than Chinese patients to have higher MACE rates at one month [6.6% vs. 5.2% vs. 4.1% respectively (p = 0.004)].

Myocardial infarction was seen in 1.0% versus 0.2% (OR4.49 95%CI 1.91-10.56 p = 0.001) (Figure 3) in Indian versus Chinese patients and overall MACE was 6.6% versus 4.1% (OR1.64 95%CI 1.23-2.19 p = 0.001). The frequency of revascularization procedures during one-month follow-up also differed by ethnicity (Figure 1). Compared to Chinese patients, Malay and Indian patients were significantly more likely to require revascularization procedures at one-month (3.8% vs. 4.8% vs. 6.2% respectively, p = 0.0012).

Discussion

Our results demonstrate higher risks of adverse cardiovascular outcome among Indian and Malay patients, compared to Chinese patients, after PCI. This was largely due to higher rates of myocardial infarction, death and repeat revascularization among Indians and higher rates of repeat revascularization among Malays.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large study to report on the differences in outcomes among Asian patients.

We have found that Indian patients who were referred for PCI have more cardiovascular risk factors at baseline than Chinese patients. Indians had higher rates of diabetes mellitus and family history of coronary artery disease compared to Chinese. Indian patients also presented more often with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction that required primary PCI. This was associated with higher rates of short-term major adverse cardiovascular events among Indian patients, driven by higher rates of myocardial infarction and need for repeat revascularization procedures after one-month.

The higher rates of mortality up to six months among Indians compared to Chinese concur with previous reports of excess mortality from ischemic heart disease amongst Indians [10, 12]. This finding is similar to earlier reports of South Asian patients living in other parts of the world who experience higher risk of death over the ensuing six months than the local population [14, 15].

Given the considerably higher rates of MACE among Indian and Malay patients in our population, it is important to identify potential causes for these findings [11, 16]. It has been reported that Asian Indians are more susceptible to the development of diabetes mellitus than Chinese and Malays [15–18] that may account for worse outcomes. However, we have adjusted for these differences in risk factors and the resulting outcomes are still much worse amongst Indians and Malays.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, this study is based on registry data and only included patients who were referred for PCI for CAD. This would have excluded patients with underlying CAD who were not referred for PCI or did not require PCI due to either physician or patient choice. The resulting clinical outcomes of these patients would be quite different due to referral bias.

Secondly, the endpoints were not independently adjudicated. However, this is study represents a significant sample of a multi-ethnic population for which the primary and secondary outcomes were reviewed carefully from medical records and telephone follow-up over time.

Given these findings, it is likely that there are other yet unknown mechanisms that may account for the disparity in clinical outcomes amongst the three major ethnic groups. It is unlikely that these differences can be explained on the basis of co-morbidities alone. It would be important in future studies to explore the role of other treatment factors like compliance, racial differences in rates of disease progression or response to drug therapy on cardiovascular outcomes in these Asian subpopulations.

Conclusions

Despite advances in CAD management, differences in racial outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention are evident in our study. The larger burden of cardiovascular disease risk factors among the ethnic groups may not completely explain these differences. To fully understand this ethnic inequality in cardiovascular outcomes, we will require further research in order to elucidate the reasons that underlie these differences and work towards reducing these disparities.

References

Gillum RF, Gillum BS, Francis CK: Coronary revascularization and cardiac catheterization in the United States: trends in racial differences. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997, 29 (7): 1557-1562. 10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00089-2.

Marks DS, Mensah GA, Kennard ED, Detre K, Holmes DR: Race, baseline characteristics, and clinical outcomes after coronary intervention: The New Approaches in Coronary Interventions (NACI) registry. Am Heart J. 2000, 140 (1): 162-169. 10.1067/mhj.2000.106645.

Chen MS, Bhatt DL, Chew DP, Moliterno DJ, Ellis SG, Topol EJ: Outcomes in African Americans and whites after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Med. 2005, 118 (9): 1019-1025. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.12.035.

Leborgne L, Cheneau E, Wolfram R, Pinnow EE, Canos DA, Pichard AD, et al: Comparison of baseline characteristics and one-year outcomes between African-Americans and Caucasians undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2004, 93 (4): 389-393. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.10.029.

Mastoor M, Iqbal U, Pinnow E, Lindsay J: Ethnicity does not affect outcomes of coronary angioplasty. Clin Cardiol. 2000, 23 (5): 379-382. 10.1002/clc.4960230515.

Maynard C, Wright SM, Every NR, Ritchie JL: Racial differences in outcomes of veterans undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. Am Heart J. 2001, 142 (2): 309-313. 10.1067/mhj.2001.116956.

Melsop K, Brooks MM, Boothroyd DB, Hlatky MA: Effect of race on the clinical outcomes in the bypass angioplasty revascularization investigation trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009, 2 (3): 186-190. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.802942.

Minutello RM, Chou ET, Hong MK, Wong SC: Impact of race and ethnicity on inhospital outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention (report from the 2000-2001 New York State Angioplasty Registry). Am Heart J. 2006, 151 (1): 164-167. 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.02.029.

Slater J, Selzer F, Dorbala S, Tormey D, Vlachos HA, Wilensky RL, et al: Ethnic differences in the presentation, treatment strategy, and outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention (a report from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Dynamic Registry). Am J Cardiol. 2003, 92 (7): 773-778. 10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00881-6.

Hughes K, Lun KC, Yeo PP: Cardiovascular diseases in Chinese, Malays, and Indians in Singapore. I. Differences in mortality. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1990, 44 (1): 24-28. 10.1136/jech.44.1.24.

Hughes K, Yeo PP, Lun KC, Thai AC, Sothy SP, Wang KW, et al: Cardiovascular diseases in Chinese, Malays, and Indians in Singapore. II. Differences in risk factor levels. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1990, 44 (1): 29-35. 10.1136/jech.44.1.29.

Mak KH, Chia KS, Kark JD, Chua T, Tan C, Foong BH, et al: Ethnic differences in acute myocardial infarction in Singapore. Eur Heart J. 2003, 24 (2): 151-160. 10.1016/S0195-668X(02)00423-2.

Tziomalos K, Weerasinghe CN, Mikhailidis DP, Seifalian AM: Vascular risk factors in South Asians. Int J Cardiol. 2008, 128 (1): 5-16. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.11.059.

Wilkinson P, Sayer J, Laji K, Grundy C, Marchant B, Kopelman P, et al: Comparison of case fatality in south Asian and white patients after acute myocardial infarction: observational study. BMJ. 1996, 312 (7042): 1330-1333.

McKeigue PM, Miller GJ, Marmot MG: Coronary heart disease in south Asians overseas: a review. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989, 42 (7): 597-609. 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90002-4.

Lee J, Heng D, Chia KS, Chew SK, Tan BY, Hughes K: Risk factors and incident coronary heart disease in Chinese, Malay and Asian Indian males: the Singapore Cardiovascular Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2001, 30 (5): 983-988. 10.1093/ije/30.5.983.

Yeo KK, Tai BC, Heng D, Lee JM, Ma S, Hughes K, et al: Ethnicity modifies the association between diabetes mellitus and ischaemic heart disease in Chinese, Malays and Asian Indians living in Singapore. Diabetologia. 2006, 49 (12): 2866-2873. 10.1007/s00125-006-0469-z.

Ounpuu S, Yusuf S: Singapore and coronary heart disease: a population laboratory to explore ethnic variations in the epidemiologic transition. Eur Heart J. 2003, 24 (2): 127-129. 10.1016/S0195-668X(02)00611-5.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2261/11/22/prepub

Acknowledgements and Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

A S. Koh is the first author who analyzed and interpreted data, drafted and completed the manuscript. L W. Khin made substantial contributions to statistical analysis. L M Choi participated in conception, design and acquisition of the data. L L. Sim participated in conception, design and acquisition of the data. T S. Chua was involved in critical appraisal of the manuscript. T H. Koh was involved in the coordination and acquisition of data. J W. Tan was participated in the design and interpretation of data. S. Chia conceived and designed the manuscript, analyzed and interpreted the data, involved in drafting of the manuscript and revising it for content.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Koh, A.S., Khin, L.W., Choi, L.M. et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in asians- are there differences in clinical outcome?. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 11, 22 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-11-22

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-11-22