Abstract

Background

Pollens from different olive (Olea europaea L.) cultivars have been shown to differ significantly in their content in Ole e 1 and in their overall allergenicity. This allergen is, in addition, characterized by a high degree of polymorphism in its sequence. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the putative presence of divergences in Ole e 1 sequences from different olive cultivars.

Results

RNA from pollen individually collected from 10 olive cultivars was used to amplify Ole e 1 sequences by RT-PCR, and the sequences were analyzed by using different bioinformatics tools. Numerous nucleotide substitutions were detected throughout the sequences, many of which resulted in amino acid substitutions in the deduced protein sequences. In most cases variability within a single variety was much lower than among varieties. Key amino acid changes in comparison with "canonical" sequences previously described in the literature included: a) the substitution of C19-relevant to the disulphide bond structure of the protein-, b) the presence of an additional N-glycosylation motif, and c) point substitutions affecting regions of Ole e 1 already described like relevant for the immunogenicity/allergenicity of the protein.

Conclusion

Varietal origin of olive pollen is a major factor determining the diversity of Ole e 1 variants. We consider this information of capital importance for the optimal design of efficient and safe allergen formulations, and useful for the genetic engineering of modified forms of the allergen among other applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Olive (Olea europaea L.) pollen produces respiratory allergy in the populations of geographical areas where this plant is widely cultivated, mainly the countries surrounding the Mediterranean Sea and several regions of North, South America and Australia [1, 2]. Up to date, 10 allergens, i.e. Ole e 1 to Ole e 10, have been purified and characterized in Olea europaea L. pollen [3, 4]. The major allergen Ole e 1 is a protein of 18–22 kDa, displaying acidic pI and different forms of N-glycosylation [5, 6]. Besides its high homology to its counterparts in other members of the Oleaceae family, such as lilac and privet [7, 8], Ole e 1 exhibits relevant similarity with the products of genes Lat52 from tomato, Zm13 from maize and several extensins from Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum among other proteins. These proteins have been indexed like members of the denominated "pollen proteins of the Ole e 1 family" (Accession number: PF01190) within the Pfam protein families database [9]. These plant pollen proteins are structurally related. They are most probably secreted and consist of about 145 residues. There are 6 cysteines conserved in the sequence of these proteins which seem to be involved in disulphide bonds. Although their biological function is not yet known, they have been suggested to be involved in important events during pollen formation, such as hydration, germination and/or pollen tube growth [10–13].

Pollen from different olive cultivars considerably differ in their capacity to bind IgE antibodies and to elicit an allergenic response, as tested by different in vivo and in vitro techniques [14–17]. Noteworthy, quantitative differences in the content of Ole e 1 have been described in the pollen of several olive cultivars, which are positively correlated with the amounts of Ole e 1 transcripts present in these pollens [17]. Although these quantitative differences are likely responsible for the different reactivity of patients to the pollen from different cultivars, the concomitances of other factors can not be discarded. In this context, the role of other major and secondary allergens from olive pollen, and the presence of divergent epitopes of Ole e 1 in the different cultivars should be evaluated.

Ole e 1 presents numerous microheterogeneities in its nucleotide sequence [18, 19]. These nucleotide substitutions result in many cases in amino acid changes in the natural protein [20], which have been reported to influence the binding of IgE molecules to Ole e 1 proteins [21]. However, up to date, the presence of such polymorphism has never been related to the genetic origin of the pollen tested. On the contrary, commercially available pollen from uncertain origin or pollen mixes from different sources seems to be the common material used for biochemical, molecular and immunological characterization of allergens. The presence of an extremely wide germplasm in the olive, with over 1200 varieties cultivated over the world [22] clearly point to this genetic variability as a putative cause of inconsistency for Ole e 1 sequence. This work explores the molecular variability of Ole e 1 allergen throughout a number of olive cultivars and discusses putative implications of such polymorphism in both the biology of the plant and the development of the allergic symptoms.

Results

Sequences analysis

Ole e 1 RT-PCR amplification of RNA from pollen of eight olive cultivars, and further sequencing of three clones from each cloned PCR product resulted in twenty four raw sequences. The nucleotide sequences obtained were deposited in the GenBank™/EMBL Database (Table 1).

These sequences were individually analyzed by the nucleotide-nucleotide BLAST (blastn) program [23]. Higher identity scores included in all cases the different variants of Ole e 1 present in the nr (non-redundant All GenBank+EMBL+DDBJ+PDB sequences – but no EST, STS, GSS, environmental samples or phase 0, 1 or 2 HTGS sequences-) database, including the following accessions: X76396.1, X76397.1, Y12426.1, X76395.1, AY159880.1, S75766.1, Y12428.1 and Y12427.1. Significant scores (E. value threshold: 2e-99) also corresponded to Ole e 1-like proteins from Ligustrum vulgare (X77788.1, X77787.1), Fraxinus excelsior (AF526295.1, AY652744.1, AY377127.1), Syringa vulgaris (X76539.1, X76540.1, X76541.1) and wild olive -acebuche- (AY159881.1). The identity analysis involved the whole sequence of these variants, with the exception of a short 5' fragment of 38–44 nucleotides including the ATG initiation codon which was absent in the RT-PCR amplified fragments as the result of the amplification strategy used.

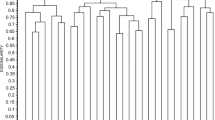

Different tree views were computed based on BLAST pairwise alignment of the query sequences to the sequences searched in the databases (see Fig. 1 as an example). The tree views generated clearly displayed that sequence differences were appreciably higher among olive cultivars than within the same cultivar. Differences between some cultivars (i.e. Picual and Bella de España) were in some cases higher than between olive cultivars and Ole e 1-like proteins from members of the Oleaceae family.

Tree view corresponding to the higher scores (E. value threshold: 2e-99) of a BLAST pairwise alignment of the submitted Ole e 1 sequences within the nr databases. Ole e 1 sequences of the same cultivar origin are frequently grouped in the same branch of the tree. Distances among some olive cultivars (i.e. Picual and Bella de España) were in some cases larger than between olive cultivars and Ole e 1-like proteins from members of other genera of the Oleaceae family (i.e. Bella de España and Fraxinus/Ligustrum).

Detailed analysis of sequences was performed after multiple alignment of the 24 nucleotide sequences obtained, using ClustalW software. The analysis revealed the presence of microheterogeneities at several positions, particularly in the 5' coding region and the 3' non-coding region [see Additional file 1]. However, the main variability was found in the sequences corresponding to Bella de España, in which a fragment of 38 nucleotide was absent from the 3' non-coding region. The reported changes in many cases also affected the corresponding deduced amino acid sequences, as displayed in Figure 2.

A: Multiple alignment of the deduced Ole e 1 amino acid sequences displayed in Figs 1, Additional file 1, and the amino acid sequence of Ole e 1 experimentally determined by Edman degradation (20). Conserved Cys at positions 22, 43, 78, 90 and 131 are pointed by arrows (discontinuous line arrow for the semi-conserved 19C). Predicted N-glycosylation motifs are indicated by boxes. Immunodominant T-cell epitopes (A, B and C), experimentally determined by [24] are showed by brackets. IgE and IgG B-cell immunodominant regions of Ole e 1, determined by [25] are respectively shown by stars and bars. Numbering follows the experimental Ole e 1 sequence obtained by Edman degradation. B: Sequence conservation index calculated by Jalview programme according to [53]. Conservation is measured as a numerical index (0 to 10) reflecting the conservation of physico-chemical properties for each column of the alignment: identities score highest, and the next most conserved group contain substitutions to amino acid lying in the same physico-chemical class.

The numerical analysis of the nucleotide and amino acid substitutions (including conservative substitutions) detected among the sequences obtained and those showing a relatively high percentage of identity is displayed in Additional file 2. The percentage of identical nucleotides between the Ole e 1 sequences ranged between 86 to 100%, whereas the percentage of identical nucleotides between Ole e 1 and Ole e 1-like sequences from other Oleaceae members ranged between 86 to 93%.

When the predicted amino acid sequences were analyzed, the percentage of identical amino acids ranged between 82 and 100% among the Ole e 1 sequences (84 to 96% between Ole e 1 and Ole e 1-like sequences from other Oleaceae members). After considering conservative changes, these percentages raised into ranges of 90–100% for Ole e 1 sequences, and 90–98% between Ole e 1 and Ole e 1-like sequences.

Amino acid substitutions were spread over the whole Ole e 1 sequence with the exception of several regions, which were extremely conserved throughout all the sequences analyzed, independently of the variety of origin (Figure 2). These conserved regions included those corresponding to 5 out of the 6 Cys conserved residues at positions 22, 43, 78, 90 and 131, and a putative N-glycosylation site at position 111.

Several highly conserved sequences also corresponded to immunodominant T-cell epitopes of Ole e 1 allergen characterized by [24] and amino acid residues implicated in IgG and IgE binding [25]. Some of the predicted sequences were identical to that described by [20], which was obtained for Ole e 1 after Edman degradation. These identical sequences were obtained from cultivars Lucio, Menara and Picholine marocaine, in addition to the sequence S75766, which was previously obtained in our laboratory from an undetermined source of pollen.

On the other hand, the analysis using different bioinformatic tools and those sequences described as relevant for the allergenic response [24, 25] allowed us to identify key amino acid substitutions in the sequences corresponding to several cultivars, which are listed in Additional file 3. These substitutions included: a) Cys residues substituted at position 19 in 6 sequences (3 from the cultivar Bella de España, 2 from the cultivar Arbequina, and that corresponding to the wild olive -acebuche-) b) an extra site for potential N-glycosylation at position 50, predicted by the ScanProsite software within the three amino acid sequences obtained from the cultivar Bella de España and c), point substitutions in those sequences described like immunodominant T-cell epitopes of Ole e 1 allergen characterized by [24] and amino acid residues implicated in IgG and IgE binding [25].

Discussion

Polymorphism is a frequent feature for allergens molecules. Different degrees of polymorphism have been described in the allergens of many different sources, including house dust mites [26], foods [27, 28] and allergens from different grass and tree pollens [29, 30]. However, although allergen polymorphism is beginning to be deeply characterized at the molecular level, little is known in many cases regarding the origin of such polymorphism. In several cases, allergen polymorphism has been attributed to the presence of multigene protein families [31]. In other allergens, the presence of post-translational modifications may also determine the presence of multiple forms of the allergen, as is the case of Ole e 1 [32]. In apple (Malus domestica), up to 18 Mal d 1 genes have been characterized. Allelic diversity regarding this allergen has been considered as a major explanation for the considerable differences in allergenicity, widely described among apple cultivars [28]. The high rate of nucleotide substitutions detected in Ole e 1 indicates that these substitutions are unlikely to represent in vitro artefacts as the result of error incorporations by the Pfu polymerase used. The present paper demonstrates that Ole e 1 polymorphism is clearly linked to the cultivar (genetic) origin of the pollen analyzed, and therefore represents the basis for further research in relation to the biological function and the allergenicity of this gene product.

It was previously reported by us [17] that pollen from different olive cultivars exhibit quantitative differences in the content of Ole e 1, which were positively correlated with the amounts of Ole e 1 transcripts present in these pollens. The results shown here also indicate that qualitative differences in the Ole e 1 allergen also occur in these pollens. Three major parameters have been demonstrated to influence the reactivity of Ole e 1 to IgG and IgE antibodies in a higher or lower degree [21]: three-dimensional (3D)-folding, the glycan component and several point changes of the amino acid sequence. The present paper reports, on the basis of the sequences obtained, that modifications in these features can be related to the genetic origin of the pollen analyzed.

Sequence substitutions in Ole e 1 from different varieties are not equally distributed over the whole sequence. Conserved regions include those corresponding to the conserved Cysteine residues at positions 22, 43, 78, 90 and 131. The absence up to date of a 3D model for Ole e 1 or any Ole e 1-like protein with significant identity to this protein within the PDB databases makes impossible to determine precisely the putative involvement of amino acid substitutions into conformational changes of the protein, which may affect either the biological function or the IgG/IgE binding ability of the protein. However, we may speculate about the potential changes. Substitution of 19C may dramatically alter tertiary structure of the Ole e 1 protein, as the presence of a disulphide bond between 19C–90C in Ole e 1 was previously established [33]. The conformation proposed by these authors is supposed to be shared by most members of proteins of the Ole e 1 family, where an identical distribution of the 6 cysteine residues is widely maintained, no matter their phylogenetic distances or relationships. As a consequence, important modifications in the reactivity of antibodies to conformational epitopes might be expected, as the binding of Ole e 1 to human IgE antibodies has been shown to be highly dependent on the integrity of the disulphide bridges [21]. The putative absence of the 19C–90C disulfide bridge in some Ole e 1 forms, could also represent an additional hint against the proposed homology between the Kunitz protein family and Ole e 1-related pollen proteins [34, 35], since disulfide arrangement is a typical feature for the classification of the protease inhibitor protein family [36]. The presence of free – SH groups (corresponding to the 90C) in these Ole e 1 forms with substitutions in the 19C residue, and therefore unable to form the 19C–90C intramolecular bridge, could alternatively promote the formation of dimeric forms of the protein throughout the formation of intermolecular disulphide bridges. It has been described that the SDS-PAGE pattern of Ole e 1 frequently exhibits a faint band of 40 kDa as a result of the presence of a 20 kD dimer [20], which may account up to 5% of Ole e 1. Our observations show that these dimeric forms of Ole e 1 are relatively more abundant in the extracts of Bella de España and Arbequina than in the rest of cultivars examined. Monomeric and dimeric forms of Ole e 1 also react differentially to a panel of monoclonal antibodies to Ole e 1 and to sera from olive-allergic patients (unpublished results).

The role of the glycan moiety of Ole e 1 in antibody binding has also been established [6, 7, 21, 37]. These authors concluded that carbohydrate moieties may constitute determinants possessing a relative significance in the binding of IgE from hypersensitive patients, not only in the Ole e 1 allergen but also in other allergenic glycoproteins. In this context, the presence of modifications, such as the putative presence of an extra site for N-glycosylation which is reported here for the cultivar Bella de España may represent an important modification in the allergenic capability of the Ole e 1 protein of this pollen, which should be further tested.

Several examples are available throughout the literature demonstrating that sequence changes need not be extensive to significantly alter the immunological properties (both antigenicity and allergenicity) of an allergen: genetic variation of Der p 2 produces striking effects on T cell responses and IgE binding [38]. Regarding pollen allergens, recombinant Bet v 1 allergen shows reduced IgE binding compared with its highly allergenic Bet v 1a counterpart, from which only differs in nine residues [39, 40]. On the opposite hand, recombinant rOle e 1/3c isoform of Ole e 1 [21] displays the highest degree of IgE-binding in comparison with rOle e 1/5c, rSir v 1 and rLig v 1 forms (the latest from Syringa vulgaris and Ligustrum vulgare, respectively), which present a progressively higher number of substitutions with respect to the amino acid sequence determined for Ole e 1 by Edman degradation [18–20]. Experimental evidence of the importance of certain positions of the amino acid sequence of Ole e 1 for both IgG and IgE binding and the elicitation of the allergenic response has been obtained since the nineties [21, 24, 25, 41]. As the result of these studies, B-cell, T-cell epitopes and IgE and IgG B-cell immunodominant regions of Ole e 1 have been determined. It is foreseeable that the described substitutions affecting these regions will have a particular contribution in putative changes in the allergenicity/immunogenicity of the protein.

Furthermore, the induction of minor changes and the study of variants within an allergen is a commonly proposed approach to the engineering of hypoallergens. In accordance with the results showed here, some modified allergens, or even hypoallergenic forms of Ole e 1 could naturally occur in some olive varieties. An important evidence of this approach has recently emerged after the description of the generation and further immunological testing of three hypoallergenic mutants of Ole e 1 [42]. Two out of the three mutants generated by site-directed mutagenesis of Ole e 1-specific cDNA and produced in Pichia pastoris (135Δ10 and 140Δ5 deletion mutants) were able to strongly reduce the IgE-binding capability of sera from olive pollen-allergic patients. In addition, the 135Δ10 mutant was able to maintain intact its T cell reactivity and to induce blocking antibodies. From the sequences analyzed in the present paper, those three corresponding to Bella de España showed point substitutions in 135Y, and five sequences (three from Bella de España, one from Picual, and one from acebuche) displayed substitutions throughout the 144N and the 145M positions. On the basis of this coincidence in the altered regions of Ole e 1, the allergen isoforms of Bella de España could be considered as potential hypoallergenic forms of natural origin. Experimental data obtained in our laboratory have shown that the Ole e 1 variants from Bella de España pollen display reduced binding to IgEs from olive-allergic patients in Western blotting experiments, when compared to Ole e 1 forms from other olive cultivars (unpublished results). Future analysis of epitope reactivity should include putative modifications in other immuno-relevant regions of the protein which should also comprise the N-terminus of Ole e 1, whose sequence has not been analyzed in this work.

The presence of differences in the reactivity to Ole e 1 displayed by patients from different geographical origin in Spain [3, 43, 44] could be explained by the presence of Ole e 1 polymorphism linked to the varietal origin of the pollen present in the atmosphere, as the major olive varieties are precisely and discretely distributed over geographic regions [45]. A similar finding has been described for major house dust mite allergens, where the predominant variants of Der p 2 have been found to be distinct in different regions [26].

The analysis of the sequences showed here indicates that the Ole e 1 sequences from varieties like Bella de España display a higher degree of identity with Ole e 1-like proteins from Oleaceae than with the "canonical" sequence of Ole e 1 obtained after Edman degradation [20] or other Ole e 1 sequences described in the literature or present in databases. Important implications of such relationships, particularly regarding the presence of cross-reaction phenomena are expected: i.e. the exposure to pollen from such olive varieties (mainly anemophilous, and therefore highly represented like an aeroallergen in broad areas) may spread, or even trigger patient's reactivity to pollens from mainly entomophilous, and only locally represented plants species with low frequency of allergic sensitization like Ligustrum, Fraxinus, Syringa and other Oleaceae [46, 47].

A large variety of morphological, biometric, biochemical and molecular characters have been widely used to describe and characterize olive germplasm [48]. Molecular markers include RFLPs, RAPDs, AFLPs, micro- and mini-satellite sequences. The low level of intra-varietal polymorphism showed by Ole e 1 sequences, compared to the higher polymorphism present among cultivars could be derived to the use of allergen sequences as molecular marker for olive breeding purposes. As an example, Ole e 1 sequences could be used as an additional marker in order to complement the discrimination between closely related olive cultivars, where other markers produce no or little differential patterns. The present study shows how two very closely related cultivars are recognized like different, on the basis of Ole e 1 similarity. This is the case of cultivars Picholine marocaine and Menara, the later considered a clonal selection of the former, raised in Morocco on the basis of better production, sooner come into bearing, and easier propagation from cuttings [49]. The increasing number of molecular markers available will help to elucidate important questions regarding the olive culture, which remain unanswered. Conflicting hypotheses exist about the phylogenetic relationships between Olea europaea L. and Olea-related species, between wild and cultivated forms of Olea europaea L. and about the origin of the culture [50]. Other biological implications of the allergen polymorphism in olive pollen with regard to pollen production and performance have been recently addressed [51].

Although much effort must yet be put into the characterization of olive pollen allergen polymorphism in relationship to the varietal origin, the advantages of the knowledge generated are obvious, and a number of applications are foreseeable. The study of natural variants will lead to the development of methods for improving efficacy and safety of the extracts currently in use for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, as well as the routine trials for quality control of many laboratories. New strategies for the design of hypoallergenic variants will be considered and natural pollen extracts from different varietal sources could be used in order to further personalize patient's reactivity or like natural hypoallergenic extracts, as an alternative or in addition to the use of recombinant allergens. Finally, advances in the breeding of hypoallergenic cultivars might also be directed by a broader knowledge of the genetic basis of this variability. The clinical implications of allergen polymorphism in the olive pollen are examined in detail in [51], in particularly how cultivar differences may affect extract quality, diagnostic and therapeutic efficacy and safety, and the development of new vaccines.

Conclusion

The sequence polymorphism present in the olive pollen major allergen Ole e 1 is highly dependent on the genetic origin of the pollen analyzed. Predicted Ole e 1 proteins from different olive cultivars are likely to display different qualitative properties. These differences have a number of implications in olive pollen biology. They also should be considered for optimal design of allergen formulations, including the design of recombinant allergens, in order to improve both their efficiency and safety.

Methods

Plant material

Olive (Olea europaea L.) pollen was individually collected during May and June 2002–2005 from selected olive trees of cultivars Lucio, Picual, Loaime, Hojiblanca, Arbequina and Bella de España (Olive World Germplasm Bank, Córdoba, Spain), and Picholine marocaine and Menara (olive collection of Ain Taoujdat, Meknes, Morocco). Pollen samples were collected in large paper bags by vigorously shaking the inflorescences, sequentially sieved through 150 and 50 μm mesh nylon filters to eliminate debris and maintained at -80°C.

Amplification and cloning of Ole e 1 transcripts

RT-PCR procedures were used as described by [17] with minor modifications. Briefly, total RNA was isolated from mature pollen of each cultivar using an RNeasy Plant Total RNA kit (Quiagen). cDNA synthesis was carried out by using M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (MBI Fermentas) and a poly-dT RACE adaptor (5'-GACTCGAGTCGACATCGA(T)17-3') as a primer, following manufacturer's indications. PCR amplifications were carried out from 250 ng of the template cDNAs, by using 5 ρ mol of the primer (5'-ACCTCCAGTTTCTCAATTTCAC-3') as forward and equal amount of the poly-dT RACE adaptor described above. The mixtures were denatured at 95°C for 3 min and subjected to PCR amplification in a Progene Thermocycler (Techne) for 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 57°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min, using Pfu polymerase (Stratagene). After analyzing the PCR products by gel electrophoresis, the bands obtained (650 bp) were cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), according to the manufacturer's instructions. At least three clones from each cultivar were sequenced.

Bioinformatic analysis of Ole e 1 sequences

Nucleotide sequences were analyzed by the nucleotide-nucleotide BLAST (blastn) program [23]. BLAST pairwise alignments and tree view were generated by using the fast minimum evolution method and maximum sequence difference of 0.75.

Protein sequence alignments were performed by the ClustalW software [52] and viewed using the Jalview viewer 2.2 [53]. Conservation index was calculated as described by [54]. Ole e 1 protein sequences were searched for different motifs with the ScanProsite on-line facilities at the ExPASy Proteomics Server [55].

References

Wheeler AW: Hypersensitivity to the allergens of the pollen from olive tree (Olea europaea). Clin Exp Allergy. 1992, 22: 1052-1057. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1992.tb00129.x.

Liccardi G, D'Amato M, D'Amato G: Oleaceae pollinosis: a review. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1996, 111: 210-217.

Rodríguez R, Villalba M, Monsalve RI, Batanero E, González EM, Monsalve RI, Huecas S, Tejera ML, Ledesma A: Allergenic diversity of the olive pollen. Allergy. 2002, 57: 6-15. 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.057s71006.x.

Barral P, Batanero E, Palomares O, Quiralte J, Villalba M, Rodríguez R: A major allergen from pollen defines a novel family of plant proteins and shows intra- and interspecies cross-reactivity. J Immunol. 2004, 172: 3644-3651.

Villalba M, López-Otín C, Martín-Orozco E, Monsalve RI, Palomino P, Lahoz C, Rodríguez R: Isolation of three allergenic fractions of the major allergen from Olea europaea pollen and N-terminal amino acid sequence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990, 172: 523-528. 10.1016/0006-291X(90)90704-Q.

Batanero E, Villalba M, Rodríguez R: Glycosylation site of the major allergen from olive tree. Allergenic implications of the carbohydrate moiety. Mol Immunol. 1994, 31: 31-37. 10.1016/0161-5890(94)90135-X.

Batanero E, Villalba M, López-Otín C, Rodríguez R: Isolation and characterization of an olive allergen-like protein from lilac. Sequence analysis of three cDNA encoding the protein isoforms. Eur J Biochem. 1994, 221: 187-193. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18728.x.

Batanero E, González de la Peña MA, Villalba M, Monsalve RI, Martín-Esteban M, Rodríguez R: Isolation, cDNA cloning and expression of Lig v 1, the major allergen from privet pollen. Clin Exp Allergy. 1996, 26: 1401-1410. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1996.tb00542.x.

Bateman A, Coin L, Durbin R, Finn RD, Hollich V, Griffiths-Jones S, Khanna A, Marshall M, Moxon S, Sonnhammer ELL, Studholme DJ, Yeats C, Eddy SR: Database Issue. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32: D138-D141. 10.1093/nar/gkh121.

Alché JD, Castro AJ, Olmedilla A, Fernández MC, Rodríguez R, Villalba M, Rodríguez-García MI: The major olive pollen allergen (Ole e I) shows both gametophytic and sporophytic expression during anther development, and its synthesis and storage takes place in the RER. J Cell Sci. 1999, 112: 2501-2509.

Stratford S, Barne W, Hohorst DL, Sagert JG, Cotter R, Golubiewski A, Showalter AM, McCormick S, Bedinger P: A leucine-rich repeat region is conserved in pollen extensin-like (Pex) proteins in monocots and dicots. Plant Mol Biol. 2001, 46: 43-56. 10.1023/A:1010659425399.

Tang B, Banerjee B, Greenberger PA, Fink JN, Kelly KJ, Kurup VP: Antibody binding of deletion mutants of Asp f 2, the major Aspergillus fumigatus allergen. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000, 270: 1128-1135. 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2546.

Alché JD, M'rani-Alaoui M, Castro AJ, Rodríguez-García MI: Ole e 1, the major allergen from olive (Olea europ aea L.) pollen, increases its expression and is released to the culture medium during in vitro germination. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004, 45: 1149-1157. 10.1093/pcp/pch127.

Waisel Y, Geller-Bernstein C, Keynan N, Arad G: Antigenicity of the pollen proteins of various cultivars of Olea europaea. Allergy. 1996, 51: 819-825. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1996.tb00028.x.

Carnés-Sánchez J, Iraola VM, Sastre J, Florido F, Boluda L, Fernández-Caldas E: Allergenicity and immunochemical characterization of six varieties of Olea europaea. Allergy. 2002, 57: 313-318. 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.03384.x.

Conde-Hernández J, Conde-Hernández P, González-Quevedo MT, Conde-Alcañiz MA, Conde-Alcañiz EM, Crespo-Moreira P, Cabanillas-Platero M: Allergy. 2002, 60-65. 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.057s71060.x. Suppl 71

Castro AJ, Alché JD, Cuevas J, Romero PJ, Alché V, Rodríguez-García MI: Pollen from different olive tree cultivars contains varying amounts of the major allergen Ole e 1. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2003, 131: 164-173. 10.1159/000071482.

Villalba M, Batanero E, Monsalve RI, González de la Peña MA, Lahoz C, Rodríguez R: Cloning and expression of Ole e I, the major allergen from olive tree pollen. Polymorphism analysis and tissue specificity. J Biol Chem. 1994, 269: 15217-15222.

Lombardero M, Barbas JA, Moscoso del Prado J, Carreira J: cDNA Sequence analysis of the main olive allergen, Ole e I. Clin Exp Allergy. 1994, 24: 765-770. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1994.tb00988.x.

Villalba M, Batanero E, López-Otín C, Sánchez LM, Monsalve RI, González de la Peña MA, Lahoz C, Rodríguez R: The amino acid sequence of Ole e I, the major allergen from olive tree (Olea europaea) pollen. Eur J Biochem. 1993, 216: 863-869. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18208.x.

González E, Villalba M, Lombardero M, Aalbers M, Van Ree R, Rodríguez R: Influence of the 3D-conformation, glycan component and microheterogeneity on the epitope structure of Ole e 1, the major olive allergen. Use of recombinant isoforms and specific monoclonal antibodies as immunological tools. Mol Immunol. 2002, 39: 93-101. 10.1016/S0161-5890(02)00044-5.

Bartolini G, Prevost G, Messeri C: Olive tree germplasm: descriptor lists of cultivated varieties in the world. Acta Hort. 1994, 365: 116-118.

Altschul FD, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ: Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990, 215: 403-410.

Cárdaba B, del Pozo V, Jurado A, Gallardo S, Cortesano I, Arrieta I, del Amo A, Tramón P, Florido F, Sastre J, Palomino P, Lahoz C: Olive pollen allergy: searching for immunodominant T-cell epitopes on the Ole e 1 molecule. Clin Exp Allergy. 1998, 28: 413-422. 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1998.00190.x.

González E, Villalba M, Quiralte J, Batanero E, Roncal F, Albar JP, Rodríguez R: Analysis of IgE and IgG B-cell immunodominant regions of Ole e 1, the main allergen from olive pollen. Mol Immunol. 2006, 43: 570-578. 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.04.015.

Piboonpocanun S, Malainual N, Jirapongsananuruk O, Vichyanond P, Thomas WR: Genetic polymorphisms of major house dust mite allergens. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006, 36: 510-516. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02464.x.

Hales BJ, Bosco A, Mills KL, Hazell LA, Loh R, Holt PG, Thomas WR: Isoforms of the major peanut allergen Ara h 2: IgE binding in children with peanut allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2004, 135: 101-107. 10.1159/000080652.

Gao ZS, van de Weg WE, Schaart JG, van der Meer IM, Kodde L, Laimer M, Breiteneder H, Hoffmann-Sommergruber K, Gilissen LJ: Linkage map positions and allelic diversity of two Mal d 3 (non-specific lipid transfer protein) genes in the cultivated apple (Malus domestica). Theor Appl Genet. 2005, 110: 479-491. 10.1007/s00122-004-1856-9.

Asturias JA, Arilla MC, Bartolomé B, Martínez J, Martínez A, Palacios R: Sequence polymorphism and structural analysis of timothy grass pollen profilin allergen (Phl p 11). Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997, 1352: 253-257.

Chang ZN, Peng HJ, Lee WC, Chen TS, Chua KY, Tsai LC, Chi CW, Han SH: Sequence polymorphism of the group 1 allergen of Bermuda grass pollen. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999, 29: 488-496. 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.00523.x.

Bond JF, Garman RD, Keating KM, Briner TJ, Rafnar T, Klapper DG, Rogers BL: Multiple Amb a I allergens demonstrate specific reactivity with IgE and T cells from ragweed-allergic patients. J Immunol. 1991, 146: 3380-3385.

Batanero E, Villalba M, Monsalve RI, Rodríguez R: Cross-reactivity between the major allergen from olive pollen and unrelated glycoproteins: Evidence of an epitope in the glycan moiety of the allergen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996, 97: 1264-1271. 10.1016/S0091-6749(96)70194-X.

González E, Monsalve RI, Puente XS, Villalba M, Rodríguez R: Assignment of the disulfide bonds of Ole e 1, a major allergen of olive tree pollen involved in fertilization. J Peptide Res. 2000, 55: 18-23. 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2000.00138.x.

Muschietti J, Dircks L, Vancanneyt G, McCormick S: LAT52 protein is essential for tomato pollen development: pollen expressing antisense LAT52 RNA hydrates and germinates abnormally and cannot achieve fertilization. Plant J. 1994, 6: 321-338. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1994.06030321.x.

van Ree R, Hoffman DR, van Dijk W, Brodard V, Mahieu K, Koeleman CA, Grande M, van Leeuwen WA, Aalberse RC: Lol p XI, a new major grass pollen allergen, is a member of a family of soybean trypsin inhibitor-related proteins. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995, 95: 970-978. 10.1016/S0091-6749(95)70097-8.

Laskowski M, Kato I: Protein inhibitors of proteinases. Ann Rev Biochem. 1980, 49: 593-626. 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.003113.

Batanero E, Crespo JF, Monsalve RI, Martín-Esteban MI, Villalba M, Rodríguez R: IgE-binding and histamine-release capabilities of the main carbohydrate component isolated from the major allergen of olive tree pollen, Ole e 1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999, 103: 147-153. 10.1016/S0091-6749(99)70538-5.

Hales BJ, Hazell LA, Smith W, Thomas WR: Genetic variation of Der p 2 allergens: effects on T cell responses and immunoglobulin E binding. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002, 32: 1461-1467. 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2002.01500.x.

Ferreira F, Hirtenlehner K, Jilek A, Godnik-Cvar J, Breiteneder H, Grimm R, Hoffmann-Sommergruber K, Scheiner O, Kraft D, Breitenbach M, Rheinberger HJ, Ebner C: Dissection of immunoglobulin E and T lymphocyte reactivity of isoforms of the major birch pollen allergen Bet v 1: potential use of hypoallergenic isoforms for immunotherapy. J Exp Med. 1996, 183: 599-609. 10.1084/jem.183.2.599.

Markovic-Housley Z, Degano M, Lamba D, von Roepenack-Lahaye E, Clemens S, Susani M, Ferreira F, Scheiner O, Breiteneder H: Crystal structure of a hypoallergenic isoform of the major birch pollen allergen Bet v 1 and its likely biological function as a plant steroid carrier. J Mol Biol. 2003, 325: 123-133. 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01197-X.

Martín-Orozco E, Cárdaba B, del Pozo V, de Andrés B, Villalba M, Gallardo S, Rodríguez-García MI, Fernández MC, Alché JD, Rodríguez R, Palomino P, Lahoz C: Ole e I: Epitope mapping, cross-reactivity with other Oleaceae pollens and ultrastructural localization. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1994, 104: 160-170.

Marazuela EG, Rodríguez R, Barber D, Villalba M, Batanero E: Hypoallergenic mutants of Ole e 1, the major olive pollen allergen, as candidates for allergy vaccines. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007, 37: 251-260. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02632.x.

Rodríguez R, Villalba M, Monsalve RI, Batanero E, Ledesma A, González E, Tejera ML, Huecas S, García M, García I: Perfiles de reconocimiento alergénico del polen de olivo. Implicación en la diagnosis e inmunoterapia. Rev Real Acad Cienc Exactas Fís Natural (España). 1998, 92: 253-258.

Batanero E, Ledesma A, García-Cao M, Quiralte J, Florido F, Villalba M, Rodríguez R: Prevalence of olive pollen allergens and its relationship to airbone pollen counts and cross-sensitizations [abstract]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999, 103: Abstract 354

Barranco D, Trujillo I, Rallo L: Elaiografía Hispánica. Variedades de olivo en España. Edited by: Rallo L, Barranco D, Caballero JM, del Río C, Martín A, Tous J, Trujillo I. Madrid: Junta de Andalucía, MAPA and Ediciones Mundi Prensa; 2005, 47-231.

Liccardi G, D'Amato M, D'Amato G: Oleaceae pollinosis: a review. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1996, 111: 210-217.

Cariñanos P, Alcázar P, Galán C, Domínguez E: Privet pollen (Ligustrum sp.) as potencial cause of pollinosis in the city of Córdoba, south-west Spain. Allergy. 2002, 57: 92-97. 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.1o3261.x.

Ganino T, Bartolini G, Fabbri A: The classification of olive germplasm – A review. J Hortic Sci Biotech. 2006, 81: 319-334.

Walali LD, Chmitah M, Loussert R, Mahhou A, Boulouha B: Caracteres morfológicos y fisiológicos de clones de olivo de la variedad Picholine marroquí. Olivae. 1984, 3: 26-31.

Contento A, Ceccarelli M, Gelati MT, Maggini F, Baldón L, Cionini PG: Diversity of Olea genotypes and the origin of cultivated olives. Theor Appl Genet. 2002, 104: 1229-1238. 10.1007/s00122-001-0799-7.

Alché JD, Castro AJ, Jiménez-López JC, Morales S, Zafra A, Hamman-Khalifa AM, Rodríguez-García MI: Differential characteristics of olive pollen from different cultivars: biological and clinical implications. J Investig Allergol Clin Inmunol. 2007, 17 (Suppl 1): 69-75.

Chenna R, Sugawara H, Koike T, Lopez R, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG, Thompson JD: Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31: 3497-500. 10.1093/nar/gkg500.

Clamp M, Cuff J, Searle SM, Barton GJ: The Jalview Java Alignment editor. Bioinformatics. 2004, 20: 426-427. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg430.

Livingstone CD, Barton CJ: Protein sequence alignments: a strategy for the hierarchical analysis of sequence conservation. CABIOS. 1993, 9: 745-756.

Gattiker A, Gasteiger E, Bairoch A: ScanProsite: a reference implementation of a PROSITE scanning tool. Appl Bioinformatics. 2002, 1: 107-108.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff responsible for the olive germplasm collection for their invaluable cooperation, and Conchita Martínez for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by research projects JA AGL2003-00719 and MEC BFU2004-00601/BFI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

JDA and MIRG designed the study. AMHK and AJC designed the experiments. AMHK, AJC and JCJL cloned and obtained the sequences. JDA and AMHK analyzed the sequences. JDA, MIRG and AMHK prepared the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12870_2007_218_MOESM1_ESM.JPEG

Additional file 1: nucleotide sequences alignment. Multiple alignment of the Ole e 1 nucleotide sequences displayed in Fig 1. Start and stop codons (when available) are indicated by boxes. Note the absence of a 38 bp fragment in the sequences corresponding to the cultivar Bella de España. Numbering begins at the ATG start codon. (JPEG 1 MB)

12870_2007_218_MOESM2_ESM.jpeg

Additional file 2: Comparison of nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the different forms of Ole e 1 and Ole e 1-like proteins presented in Figs 1 and 2. The cells of the upper right section show the calculated percentage of identity between nucleotide sequences. Cells of the lower left section show the calculated percentages of identity between amino acid sequences in absolute terms, or after taking into account non-conservative changes only. (JPEG 4 MB)

12870_2007_218_MOESM3_ESM.jpeg

Additional file 3: Key amino acid substitutions throughout the Ole e 1 and Ole e 1-like sequences analyzed. Key substitutions analyzed include: conserved Cys residues, an extra site for potential N-glycosylation, point substitutions in those motifs described like immunodominant T-cell epitopes of Ole e 1 allergen [24], and amino acid residues implicated in IgG and IgE binding [25]. Deduced sequences fully identical to the canonical sequence of Ole e 1 obtained after Edman degradation [20] are marked by a double asterisk. (JPEG 456 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamman-Khalifa, A., Castro, A.J., Jiménez-López, J.C. et al. Olive cultivar origin is a major cause of polymorphism for Ole e 1 pollen allergen. BMC Plant Biol 8, 10 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-8-10

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-8-10