Abstract

Background

Soybean mosaic virus (SMV) is the most prevalent viral disease in many soybean production areas. Due to a large number of SMV resistant loci and alleles, SMV strains and the rapid evolution in avirulence/effector genes, traditional breeding for SMV resistance is complex. Genetic engineering is an effective alternative method for improving SMV resistance in soybean. Potassium (K+) is the most abundant inorganic solute in plant cells, and is involved in plant responses to abiotic and biotic stresses. Studies have shown that altering the level of K+ status can reduce the spread of the viral diseases. Thus K+ transporters are putative candidates to target for soybean virus resistance.

Results

The addition of K+ fertilizer significantly reduced SMV incidence. Analysis of K+ channel gene expression indicated that GmAKT2, the ortholog of Arabidopsis K+ weak channel encoding gene AKT2, was significantly induced by SMV inoculation in the SMV highly-resistant genotype Rsmv1, but not in the susceptible genotype Ssmv1. Transgenic soybean plants overexpressing GmAKT2 were produced and verified by Southern blot and RT-PCR analysis. Analysis of K+ concentrations on different leaves of both the transgenic and the wildtype (Williams 82) plants revealed that overexpression of GmAKT2 significantly increased K+ concentrations in young leaves of plants. In contrast, K+ concentrations in the old leaves of the GmAKT2-Oe plants were significantly lower than those in WT plants. These results indicated that GmAKT2 acted as a K+ transporter and affected the distribution of K+ in soybean plants. Starting from 14 days after inoculation (DAI) of SMV G7, severe mosaic symptoms were observed on the WT leaves. In contrast, the GmAKT2-Oe plants showed no symptom of SMV infection. At 14 and 28 DAI, the amount of SMV RNA in WT plants increased 200- and 260- fold relative to GmAKT2-Oe plants at each time point. Thus, SMV development was significantly retarded in GmAKT2-overexpressing transgenic soybean plants.

Conclusions

Overexpression of GmAKT2 significantly enhanced SMV resistance in transgenic soybean. Thus, alteration of K+ transporter expression is a novel molecular approach for enhancing SMV resistance in soybean.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.), a major source of protein and oil in the human diet is an important crop world wide. Soybean mosaic virus (SMV) is the most prevalent viral disease in many soybean production areas [1]. Infection with SMV causes severe symptoms, including mosaic symptoms (light and dark green areas, chlorosis, and leaf curl), necrosis (necrotic areas, stem browning, and stem-tip necrosis), and seed mottling, resulting in serious yield losses [2]. Yield losses due to SMV infection range from 8% to 50% under natural field conditions [3], to total crop loss during severe outbreaks [4].

There are seven SMV strain groups (G1-G7) and three resistance loci (Rsv1, Rsv3, and Rsv4) reported in soybean [5–8]. Soybean germplasm with Rsv1 locus are resistant to SMV strain groups G1-G3, but susceptible to strains G5-G7 [9]. In contrast, lines containing Rsv3 confer resistance to strain groups G5-G7, and condition stem-tip necrosis and/or mosaic symptoms to G1-G4 [10]. The Rsv4 locus was reported to produce seedling resistance to most SMV isolates but systemic symptoms can appear as plants mature [11]. Rsv1, 3, and 4 loci were mapped to chromosome 13, 14 and 2, respectively [11–15] and candidate genes for loci Rsv1 and Rsv3 have been putatively identified. Rsv1 was shown to link to a cluster of six non-Toll interleukin 1 receptor (TIR) nucleotide-binding site leucine rich repeat (NBS-LRR) genes [16], and recently directly verified using virus-induced gene silencing approach [17]. Furthermore, Rsv3 gene has been reported to associate with a cluster of the coiled-coil nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (CC-NB-LRR) resistance genes [18]. Overall, due to the large number of Rsv loci and alleles, multiple SMV strains, and the rapid evolution in avirulence/effector genes under R gene selective pressure, breeding to pyramid these Rsv loci is complicated.

Alternative modes of resistance to pathogen resistance are also possible. Potassium (K+), the most abundant inorganic solute in plant cells, plays many important regulatory roles in plant development and stress responses [19]. High K+ status decreases the occurrence of many diseases [20]. Perrenoud (1990) reviewed more than 2,000 studies and found a correlation between K+ status and disease incidence [21]. A high K+ status reduced bacterial, fungal, and viral diseases in 69%, 70%, and 41% of the studies, respectively. In seventeen case studies on viral disease, high K+ status reduced the incidence of viral diseases in nine studies, although five studies showed the opposite effect [22]. The correlation between K+ status of plants and their susceptibility to pathogens involves changes in their primary metabolite profiles and distribution and the hormonal pathways in plants with altered K+ status [20]. K+ status affects the function of multiple plant enzymes, and thus it changes metabolite profiles and concentrations [23]. The changes in metabolites ultimately alter the susceptibility of plants to pathogens. Furthermore, K+ status also affects plant hormonal pathways, i.e. salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonic acid (JA) pathways [20], that are involved in hypersensitive responses or aquired systemic resistance to pathogens.

Plants absorb and transport K ions using a number of transport proteins [24]. The superfamily of voltage-gated K+ channels, the Shaker family, plays roles in K+ uptake and K+ loading into xylem and phloem [25–28]. K channel proteins mediate either K+ uptake (inward-rectifying K+ channels, Kin) or K+ release (outward-rectifying K+ channels, Kout) [29]. The Arabidopsis K+ weak channel AKT2 can mediate both K+ uptake and release [30, 31]. In Arabidopsis, AKT2 is predominantly expressed in phloem tissues, guard cells, and root stellar tissues [32, 33]. AKT2 regulates transport of K+ and other small molecules in phloem through its roles in electric cell signaling and membrane excitability [28]. AKT2 may be involved in plant stress responses by adjusting potassium gradients that are important energy sources in plant vascular tissues [28, 32–34].

We observed that the incidence of SMV can be significantly reduced by application of K+ fertilizer. Analysis of K+ channel gene expression in SMV-resistant and SMV-susceptible cultivars showed that the expression of GmAKT2, the soybean inner K+ transporter gene, was induced in the resistant variety, but not in the susceptible cultivar. Overexpression of GmAKT2 significantly increased SMV resistance in the SMV susceptible cultivar Williams 82. Our results suggest that alterlation of the expression of the K+ transporter AKT2 is a novel molecular approach to genetically enhance SMV resistance in soybean.

Results

The effect of K+supply on SMV incidence

To investigate whether K+ supply affected the resistance of soybean plants to SMV, the susceptible soybean cultivar Williams 82 was planted in pots containing low-K+ soil with or without the addition of K+ fertilizer. Ten-day-old seedlings with completely unrolled unifoliate leaves in both K+-sufficient and -starvation treatments were inoculated with SMV-G7 or buffer (Mock). At 14 DAI, mild mottling and crinkled appearances were observed in the second unrolled trifoliate leaves in plants grown in low-K+ soil (Figure 1A). In contrast, only slight chlorotic spots were observed in the second unrolled trifoliate leaves of plants grown in high-K+ soil (Figure 1A). At 28 DAI, all SMV-infected soybean plants grown in K+-starvation soil showed typical SMV-susceptible symptoms: the young trifoliate leaves were severely mosaic and curled (Figure 1A). However, plants grown in high-K+ soil showed late-susceptible symptoms or resistant phenotypes (Figure 1A).

SMV resistance and K+concentrations of Williams 82 soybean plants grown under different K supplies. (A) SMV symptoms at 14 or 28 days after inoculation (DAI) with SMV in soybean plants grown in soil pots with low (36.5 mg/kg) or high (200 mg/kg) levels of K+. Unrolled unifoliate leaves of 10-day-old soybean plants were mechanically inoculated with SMV strain G7 or buffer (Mock). Photos were taken on the newest leaf of the plants, which were 2nd trifoliate leaf at 14 DAI and 7th trifoliate leaf at 28 DAI, respectively. (B) Amount of SMV RNA detected by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). The middle leaflets of the leaves of Williams 82 plants which grown in low or high K soil were sampled at 14 and 28 DAI to extract total RNA for qRT-PCR analysis of SMV. Transcript levels were calculated using the formula 2-ΔCt for the expression levels relative to GmACTIN. (C) K+ concentrations in individual leaves of plants grown in either high- or low-K soil. The first through seventh trifoliate leaves from 45-day-old soybean plants were sampled. Data represent means of three biological replicates with error bars indicating SD. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between high- and low-K soil (*P < 0.05).

To quantify the amount of SMV viral accumulation, quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was carried out to determine the amount of SMV RNA in these soybean plants. As shown in Figure 1B, SMV RNA can be detected in all inoculated plants at 14 and 28 DAI, indicating that the inoculation process was effective. The amount of SMV RNA in soybean plants grown in K+-starvation soil was significantly higher than that in K+-sufficient soil at both 14 and 28 DAI (Figure 1B), suggesting that sufficient supply of K+ could reduce SMV accumulation.

Leaf K+ concentrations from the first to the seventh trifoliate leaves of 45-day-old plants grown in high- or low-K+ soil were measured. As expected, K+ concentrations in older leaves were significantly lower than in younger leaves. K+ concentrations in the leaves of plants with sufficient K+ supplies were significantly higher than in the corresponding leaves of those in K+-starvation soil (Figure 1C).

Differential expression of GmAKT2in SMV-resistant and -susceptible genotypes in response to SMV infection

To determine whether K+ transporter genes were involved in soybean responses to SMV infection, the transcript levels of the soybean K+ channel genes GmAKT1 and GmAKT2 in response to SMV infection were investigated. Genotypes used for the assay included Rsmv1, Williams 82, and Ssmv1, which are highly-resistant, susceptible, and highly susceptible to SMV, respectively (Figure 2A). The amounts of SMV RNA accumulation detected by qRT-PCR matched to the symptoms of viral infection (Figure 2B). While the inoculation of SMV G7 significantly increased the accumulation of SMV RNA in Williams 82 and Ssmv1 plants at 14 and 28 DAI, but not in Rsmv1 plants. Compared to Williams 82, Ssmv1 plant was more susceptible to SMV infection (Figure 2B).

SMV resistance and GmAKT2 expression in three soybean genotypes. (A) Symptoms of three soybean genotypes at 14 and 28 DAI. Rsmv1, SMV highly-resistant; Williams 82, susceptible; Ssmv1, highly-susceptible. Ten-day-old soybean plants in low-K soil with unrolled unifoliate leaves were mechanically inoculated with SMV G7 or buffer (Mock). (B) Amount of SMV RNA detected by qRT-PCR. Leaves of three soybean genotypes were sampled at 14 and 28 DAI to extract total RNA for qRT-PCR analysis. Transcript levels were calculated using the formula 2-ΔCt for the expression levels relative to GmACTIN. Data represent means of three biological replicates with error bars indicating SD. (C) Relative GmAKT2 expression in three soybean genotypes at 28 DAI. Leaves of three soybean genotypes were sampled at 28 DAI to extract total RNA for qRT-PCR analysis. Transcript levels were calculated using the formula 2-ΔΔCt for the expression levels relative to GmACTIN. Data represent means of three biological replicates with error bars indicating SD.

To determine whether SMV infection will affect the expression of K+ transporters, qRT-PCR was performed to examine GmAKT1 and GmAKT2 expression in first trifoliate leaves at 28 DAI. GmAKT2 transcript levels were significantly induced by SMV infection in Rsmv1, but not in Ssmv1 (Figure 2C). In Williams 82, GmAKT2 transcript levels were induced to a lower extent than in Rsmv1 (Figure 2C). In contrast, GmAKT1 expression was not affected by SMV inoculation in all three genotypes (data not shown).

GmAKT2 was preferentially expressed in aerial tissues and induced by K+starvation

To analyze GmAKT2 expression in various soybean tissues, qRT-PCR was performed on RNA samples extracted from 6-week-old Williams 82 seedlings grown hydroponically. GmAKT2 was preferentially expressed in aerial tissues, especially leaves (Figure 3A). To determine whether the expression of GmAKT2 was affected by the status of nutrient supplies, 10-day-old soybean seedlings were transferred to solution cultures lacking nitrogen, phosphate, or potassium. GmAKT2 expression was specifically induced by K+ deficiency (Figure 3B).

GmAKT2 expression in different tissues and leaves of Williams 82 under various nutrient supply conditions. (A) Relative GmAKT2 expression in roots (R), unifoliate leaves (UL), trifoliate leaves (TL), stems (S), flowers (F), and pods (P). Soybean seedlings were grown hydroponically in growth chambers for 6 weeks. (B) Relative GmAKT2 expression in leaves of plants grown under different nutrient stress. Ten-day-old soybean seedlings were transferred into modified half-strength Hoagland hydroponic solution (CK) or solutions lacking nitrogen (-N), phosphate (-P), or potassium (-K) for 7 days. Transcript levels were calculated using the formula 2-ΔΔCt for the expression levels relative to GmACTIN. Data represent means of three biological replicates with error bars indicating SD. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between the control and treated samples (***P < 0.001).

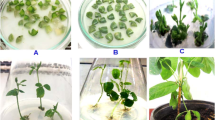

Generation of transgenic soybean overexpressing GmAKT2

The GmAKT2 full-length cDNA was amplified from Rsmv1, Williams 82, and Ssmv1, respectively. Sequence analysis showed that there is no variation on the sequence of GmAKT2 cDNA (Additional file 1: Figure S1). To assay the effect of GmAKT2 on SMV resistance, the obtained GmAKT2 cDNA driven by a modified CaMV 35S promoter (Figure 4A) was introduced into Williams 82 via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Four independent T1 transgenic lines overexpressing GmAKT2 (GmAKT2-Oe1, 2, 3, and 4) were verified by Southern blot analysis using the phosphinothricin acetyl transferase gene (bar) as the probe. Oe1, 2, 3, and 4 were four independent transgenic lines each containing a single copy (Oe1, 2, and 3) or two copies (Oe4) of the transgene (Figure 4B). qRT-PCR analysis of the T2 transgenic soybean plants showed that the transgene GmAKT2 was highly expressed in all transgenic lines (Figure 4C). The two transgenic events, Oe1 and Oe2, showing the highest levels of GmAKT2 gene expression, were selected for further experiments.

Construction and verification of GmAKT2 -overexpressing transgenic soybean plants. (A) T-DNA region of the GmAKT2 overexpression vector. LB, left border; RB, right border; bar, phosphinothricin acetyl transferase gene; P35S, CaMV double 35S promoter; T35S, CaMV 35S terminator; RFP, red fluorescence protein gene. (B) Southern blot analysis of GmAKT2-overexpressing transgenic lines. Oe1, Oe2, Oe3, and Oe4 represent four independent GmAKT2 overexpressing lines. Genomic DNA of 2-week-old T1 transgenic seedlings and the non-transformed recipient soybean genotype Williams 82 was extracted and digested with HindIII. bar gene was digoxigenin labeled and used as the probe for analysis. (C) Relative GmAKT2 expression in the leaves of the transgenic lines. T2 generations of Oe1, Oe2, Oe3, and Oe4 and WT were cultured in a hydroponic system. RNA was extracted from the leaves of 2-week-old seedlings. GmAKT2 transcript levels were determined by qRT-PCR. Data represent means of three biological replicates with error bars indicating SD. GmACTIN expression was used as the internal control.

The growth of transgenic soybean plants was compared with the growth of recipient soybean plants. No significant differences were observed between wild type and transgenic plants in the agronomic traits investigated, including plant height, stem diameter, branch number, node number, pod number, seed number, seed yield, and 100-seed weights (Table 1).

GmAKT2overexpression altered K distribution in soybean leaves

K+ concentrations in the first to seventh trifoliate leaves of 6-week-old transgenic and WT plants grown in K+-sufficient or -starvation soil were analyzed. Compared to WT plants, overexpression of GmAKT2 significantly increased K+ concentrations in young leaves (fifth through seventh trifoliate leaves) of plants grown in K+-sufficient or -starvation conditions (Figure 5A, 5B). For instance, K+ concentrations in the seventh leaves of the GmAKT2-overexpression lines were 27-40 % higher than that of the WT plants (Figure 5A, 5B). In contrast, K+ concentrations in the old leaves (first through third trifoliate leaves) of the GmAKT2-Oe plants were significantly lower than those in the WT plants (Figure 5A, 5B). These results indicated that GmAKT2 acted as a K+ transporter and affected the distribution of K+ in soybean plants.

Potassium concentrations in the leaves of WT and transgenic soybean plants grown in high- or low-K soil. WT and transgenic lines were germinated and grown in pots with soil containing high K (A, 200 mg/kg) or low K (B, 36.5 mg/kg) for 6 weeks. The first through seventh trifoliate leaves from each treatment were collected and K+ contents were measured. Data represent means of four biological replicates with error bars indicating SD. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between the WT and transgenic lines (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

GmAKT2overexpression increased SMV resistance in transgenic soybean

To determine the effect of GmAKT2 overexpression on SMV resistance, GmAKT2-Oe and WT plants were grown in pots with soil without the addition of K fertilizer in greenhouses. At least five plants were inoculated with SMV G7 or buffer in their unrolled unifoliate leaves at the VC stage [35] when the unifoliate leaves were fully expanded. Starting from 14 DAI, while severe mosaic symptoms were observed on the leaves of the WT plants, the GmAKT2-overexpression lines Oe1 and Oe2 showed no symptom of SMV infection (Figure 6A, 6B).

Overexpression of GmAKT2 enhanced SMV resistance. (A) SMV symptoms in the WT and GmAKT2 overexpression plants at 35 DAI. Ten-day-old soybean plants in low-K soil with unrolled unifoliate leaves were mechanically inoculated with SMV or buffer (Mock). (B) SMV symptoms on the newest trifoliate leaves of Williams 82 and GmAKT2-overexpressing transgenic lines Oe1 and Oe2 at 14, 28, and 35 DAI. (C) Amount of SMV RNA detected by qRT-PCR. The middle leaflets of the leaves of Williams 82, and GmAKT2-ovexpression lines Oe1 and Oe2 were sampled at 14 and 28 DAI to extract total RNA for quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Transcript levels were calculated using the formula 2-ΔCt for the expression levels relative to GmACTIN. Data represent means of three biological replicates with error bars indicating SD.

To confirm the results, qRT-PCR was used to determine SMV virus accumulation in these soybean plants. Compared to those in the Mock treatment, SMV inoculation significantly increased the amount of SMV virus in both WT and GmAKT2-Oe plants. At 14 DAI, the level of SMV RNA in WT plants were about 240 and 160 times greater than that in the GmAKT2- Oe1 and Oe2 lines, respectively (Figure 6C). With the increase of the infection process, at 28 DAI, the amount of SMV RNA in the WT was further increased. It was about 260 times as much as that of the average level of SMV RNA in GmAKT2-overexpression lines.

To verify whether the SMV resistance conferred by GmAKT2 overexpression is also effective on the other SMV stain, we tested the resistance of the transgenic plants to SMV strain G3. Results showed that the transgenic lines GmAKT2-Oe1 and Oe2 were also resistant to the infection of G3. Overexpression of GmAKT2 significantly reduced the amount of G3 RNA in plants (Additional file 1: Figure S2).

The increased virus resistance in the transgenic lines GmAKT2-Oe1 and Oe2 significantly increased their growth performance and yield when the plants inoculated SMV strain G7. As shown in Table 2, the SMV infection significantly reduced the plant height, numbers of node, pod, and seed, and the seed weight per plant of the WT soybean. In contrast, the infection of SMV virus slightly affected those agronomic traits. The difference in those traits between the infected plants and Mock was not significant.

Discussion

Arabidopsis AKT2/3 is a rectifying K+ channel that regulates K+ loading in phloem in source tissues and the unloading in sink tissues [32–34, 36]. In this study, the soybean AtAKT2 orthologous gene, GmAKT2 was overexpressed in soybean. The amino acid sequence similarity between AtAKT2 and GmAKT2 is 63% and they are phylogenetically classified in the same subcluster (Additional file 1: Figure S3). It is proposed that GmAKT2 functions similarly as AtAKT2/3 to regulate the K+ loading in phloem. Indeed, we observed that overexpression of GmAKT2 enhanced K+ reallocation from the source (older leaves, first trifoliate = oldest leaf)) to the sink (younger leaves, 7th trifoliate = youngest), which led to a significant increase in K+ concentrations in the latter (Figure 5A, 5B).

In addition to the enhancement of K+ transport, overexpression of GmAKT2 on a SMV-susceptible genotype Williams 82 significantly retarded the development of SMV and resulted in higher resistance to SMV (Figure 6A, B, C). Plant resistance to viral disease can be achieved by inhibiting viral long-distance movement. In a typical virus infection process, virus moves from the source leaves to the sink leaves via the phloem transport system [37], similar to the direction of K+ movement. A mutation in AtAKT2 was found to inhibit sugar loading into the phloem of Arabidopsis [28]. It is possible that overexpression of the soybean AKT2 resulted in changes in phloem environment to be unfavorable to virus loading, movement and unloading. Identification of the factor(s) to link the K+ transportation and virus movement will help elucidate the mechanism of how the GmAKT2 overexpression in soybean results in greater resistance to SMV.

Plant resistance to virus disease could also be achieved by inhibition of the viral multiplication. As expected, plant nutritional status affects plant health and, consequently, influences plant resistance to pathogen infection. In this study, the application of K+ fertilizer significantly reduced the SMV accumulation in the SMV-susceptible cultivar Williams 82. Thus, the sufficient K+ concentrations in soybean plant cells should be important for suppression of SMV spread. On the other hand, in the SMV-resistant GmAKT2 overexpression plants, the increase of K+ concentrations only occurred in younger leaves, but not in the older leaves. The results suggest that maintenance sufficient K+ content in young leaves should be important for soybean resistance to virus infection.

Conclusions

The soybean potassium channel gene, GmAKT2 was significantly induced by SMV inoculation in the SMV highly-resistant genotype Rsmv1, but not in the highly-susceptible genotype Ssmv1. The role of GmAKT2 on SMV resistance was evaluated in the study. Results showed that overexpression of GmAKT2 on a SMV-susceptible genotype Williams 82 enhanced the reallocation of K+ in the soybean plants and increased K+ concentrations in young leaves. Furthermore, SMV development was significantly retarded in GmAKT2-overexpressing transgenic soybean plants following SMV inoculation. These data provide a novel route for initiating molecular breeding to improve SMV resistance in soybean, an important crop world wide.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The soybean cultivar Williams 82 was used as the recipient genotype for soybean transformation. Rsmv1 and Ssmv1 were Chinese germplasm highly-resistant or highly-susceptible to SMV, respectively (Dr. Yuming Wang, personal communication).

For qRT-PCR analysis of GmAKT2 expression, soybean seeds were germinated in sterile sand for one week and transferred into modified half-strength Hoagland nutrient solution [2.5 mM KNO3, 2.5 mM Ca(NO3)2, 0.5 mM KH2PO4, 0.25 mM K2SO4, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.023 mM H3BO3, 4.57 μM MnCl2, 3.8 μM ZnSO4, 0.09 μM (NH4)6Mo7O24, 1.57 mM CuSO4, and 0.1 mM Fe-EDTA(Na)] [38] with aeration. Plants with the nutrient deficient treatments were planted in the hydroponic solution eliminating the corresponding nutrient for 7 days prior to sampling. Roots (R), unifoliate leaves (UL), trifoliate leaves (TL), stems (S), flowers (F), and pods (P) samples were collected on the 6-week-old plants grown hydroponically. Soybean plants were grown in growth chambers with a 12-hour photoperiod (1000 μmol photons m-2 sec-1) with temperature regimes of 30°C/22°C.

For soil experiments, soil with poor initial nutrient levels was collected. Nitrogen and phosphate fertilizers were applied to avoid nitrogen and phosphorus deficiency. The initial soil K+ level was 36.5 mg/kg and the K+ sufficient soil was 200 mg/kg by application of potassium sulfate. For the experiments to determine the effect of K supply on SMV incidence, 10 plants were included for each treatment. Three biological replications were employed.

For evaluation of agronomic traits, 10 WT plants (Williams 82) and 10 of each transgenic line were randomly sampled at the mature stage from the experimental station in Anhui province, China. To evaluate the effect of SMV infection on the agronomic traits, 12 WT and 12 of each transgenic line that either was Mock-treated or inoculated with SMV G7 strain at 10 day seedling stage in the greenhouse were harvested at mature stage. Plant height, branch number, node number, pod number, seed number, seed weight, and 100-seed weights were measured.

Soybean mosaic virus inoculation and sampling

Soybean plants were grown in soil pots for 10 days prior to inoculation. The SMV G7 strain was used for inoculation. Inoculums were prepared by grinding infected soybean leaf tissues in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. The unrolled unifoliate leaves were inoculated by gently rubbing with the inoculums. Plants inoculated with buffer alone were used as Mock controls.

The middle leaflets of the all trifoliate leaves of the plants at 14 and 28 DAI for RNA extraction and qRT-PCR analysis were collected and mixed for RNA extraction. Three biological replicates were applied for inoculation and sampling.

Construction of transgenic plants

The full-length cDNA of soybean GmAKT2 (Glym08g20030.1) was amplified by RT-PCR and ligated into a TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). GmAKT2 was cloned into the gateway plasmid pB7RWG2,0 (Invitrogen) under the control of the 35S promoter of cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV). The resulting construct was introduced into the Agrobacterium strain EHA101. Transgenic soybean plants were generated using the Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated cotyledon node transformation system [39]. The Williams 82 genotype was used as the recipient of the transformation.

Genomic DNA extraction and southern blot analysis

Soybean leaf genomic DNA was extracted using a modified CTAB method [40]. Thirty micrograms of genomic DNA from each sample was digested with HindIII that cuts once in the T-DNA region (Figure 4A). The digested DNA was separated on 1% agarose gels at 20 V for 20 hours followed by denaturation and neutralization. DNA samples were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes by capillary action. Nucleic acids were fixed to the membranes by cross-linking with UV-light. A digoxin (DIG)-labeled bar probe was synthesized and detected with DIG-High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit I (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA Extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNaseI digestion was performed to ensure the absence of genomic DNA (Takara, Dalian, China).

First-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus Reverse Transcriptase (M-MLV RT, Promega, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA). qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green I on a Light Cycler 480 (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The amplification program for SYBR Green I was performed as 94°C for 10 sec, 58°C for 10 sec, and 72°C for 10 sec. Triplicate quantitative assays were performed for each cDNA sample. GmACTIN was used as an internal control. Transcript levels were calculated using the formula 2-ΔCt for relative expression or 2-ΔΔCt for the expression levels relative to GmACTIN. Virus accumulation in soybean plants was estimated by qRT-PCR analysis of the SMV polyprotein gene in the SMV strain G7 or G3 genome. All primers used for RT-PCR are provided in Additional file 2: Table S1.

Measurement of potassium concentration

Soybean plants were grown in pots containing K-sufficient or -starvation soil. The first through seventh trifoliate leaves of the 6-week-old plants were collected for ion concentration analysis. Plant materials were sampled and dried at 80°C for 3 days. Then, 50 mg of dry material was dissolved in 3 ml nitric acid and 2 ml H2O2 (30 %). The digested samples were diluted to a total volume of 50 ml with ultrapure water and transferred into new tubes and analyzed using a PerkinElmer ELAN® ICP-MS system.

References

Cui X, Chen X, Wang A: Detection, understanding and control of soybean mosaic virus. Soybean - Molecular Aspects of Breeding. Edited by: Sudaric A. Shanghai: InTech, 2011:335-354.

Zheng C, Chen P, Gergerich R: Effect of temperature on the expression of necrosis in soybean infected with soybean mosaic virus. Crop Sci. 2005, 45 (3): 916-922. 10.2135/cropsci2004.0286.

Hill JH: Soybean mosaic virus. Compendium of Soybean Diseases. Edited by: Hartman GL, Sinclair JB, Rupe JC. 1999, St Paul, MN: American Phytopathological Society, 70-71. 4

Liao L, Chen P, Buss GR, Yang Q, Tolin SA: Inheritance and allelism of resistance to soybean mosaic virus in Zao18 soybean from China. J Hered. 2002, 93 (6): 447-452. 10.1093/jhered/93.6.447.

Buzzell RI, Tu JC: Inheritance of a soybean stem-tip necrosis reaction to soybean mosaic virus. J Hered. 1989, 80 (5): 400-401.

Cho EK, Goodman RM: Evaluation of resistance in soybeans to soybean mosaic virus strains1. Crop Sci. 1982, 22 (6): 1133-1136. 10.2135/cropsci1982.0011183X002200060012x.

Kiihl RAS, Hartwig EE: Inheritance of reaction to soybean mosaic virus in soybeans1. Crop Sci. 1979, 19 (3): 372-375. 10.2135/cropsci1979.0011183X001900030024x.

Ma G, Chen P, Buss GR, Tolin SA: Genetic characteristics of two genes for resistance to soybean mosaic virus in PI486355 soybean. Theor Appl Genet. 1995, 91 (6–7): 907-914.

Chen P, Ma G, Buss GR, Gunduz I, Roane CW, Tolin SA: Inheritance and allelism tests of Raiden soybean for resistance to soybean mosaic virus. J Hered. 2001, 92 (1): 51-55. 10.1093/jhered/92.1.51.

Gunduz I, Buss GR, Chen P, Tolin SA: Characterization of SMV resistance genes in Tousan 140 and Hourei soybean. Crop Sci. 2002, 42 (1): 90-95. 10.2135/cropsci2002.0090.

Hayes AJ, Ma G, Buss GR, Saghai Maroof MA: Molecular marker mapping of Rsv4, a gene conferring resistance to all known strains of soybean mosaic virus. Crop Sci. 2000, 40: 1434-1437. 10.2135/cropsci2000.4051434x.

Gore M, Hayes A, Jeong S, Yue Y, Buss G, Saghai Maroof M: Mapping tightly linked genes controlling potyvirus infection at the Rsv1 and Rpv1 region in soybean. Genome. 2002, 45: 592-599. 10.1139/g02-009.

Hwang TY, Moon JK, Yu S, Yang K, Mohankumar S, Yu YH, Lee YH, Kim HS, Kim HM, Maroof MA, Jeong SC: Application of comparative genomics in developing molecular markers tightly linked to the virus resistance gene Rsv4 in soybean. Genome. 2006, 49 (4): 380-388. 10.1139/G05-111.

Jeong SC, Kristipati S, Hayes AJ, Maughan PJ, Noffsinger SL, Gunduz I, Buss GR, Maroof MA: Genetic and Sequence Analysis of Markers Tightly Linked to the Soybean mosaic virus Resistance Gene, Rsv3. Crop Sci. 2002, 42 (1): 265-270. 10.2135/cropsci2002.0265.

Maroof MAS, Tucker DM, Skoneczka JA, Bowman BC, Tripathy S, Tolin SA: Fine mapping and candidate gene discovery of the soybean mosaic virus resistance gene, Rsv4. Plant Gen. 2010, 3 (1): 14-22. 10.3835/plantgenome2009.07.0020.

Hayes AJ, Jeong SC, Gore MA, Yu YG, Buss GR, Tolin SA, Maroof MA: Recombination within a nucleotide-binding-site/leucine-rich-repeat gene cluster produces new variants conditioning resistance to soybean mosaic virus in soybeans. Genetics. 2004, 166 (1): 493-503. 10.1534/genetics.166.1.493.

Zhang C, Grosic S, Whitham SA, Hill JH: The requirement of multiple defense genes in soybean Rsv1-mediated extreme resistance to soybean mosaic virus. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2012, 25 (10): 1307-1313. 10.1094/MPMI-02-12-0046-R.

Suh SJ, Bowman BC, Jeong N, Yang K, Kastl C, Tolin SA, Maroof MAS, Jeong S: The Rsv3 locus conferring resistance to soybean mosaic virus is associated with a cluster of coiled-coil nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat genes. Plant Gen. 2011, 4 (1): 55-64. 10.3835/plantgenome2010.11.0024.

Dennison KL, Robertson WR, Lewis BD, Hirsch RE, Sussman MR, Spalding EP: Functions of AKT1 and AKT2 potassium channels determined by studies of single and double mutants of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127 (3): 1012-1019. 10.1104/pp.010193.

Amtmann A, Troufflard S, Armengaud P: The effect of potassium nutrition on pest and disease resistance in plants. Physiol Plant. 2008, 133 (4): 682-691. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01075.x.

Perrenoud S: Potassium and Plant Health. 1990, Basel: International Potash Institute Press

Prabhu AS, Fageria NK, Huber DM: Potassium nutrition and plant diseases. Mineral Nutrition and Plant Disease. Edited by: Datnoff LE, Elmer WH, Huber DM. 2007, St Paul, MN: American Phytopathological Society, 57-78.

Ashley MK, Grant M, Grabov A: Plant responses to potassium deficiencies: a role for potassium transport proteins. J Exp Bot. 2006, 57 (2): 425-436.

Very AA, Sentenac H: Molecular mechanisms and regulation of K + transport in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2003, 54: 575-603. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134831.

Pilot G, Pratelli R, Gaymard F, Meyer Y, Sentenac H: Five-group distribution of the Shaker-like K + channel family in higher plants. J Mol Evol. 2003, 56 (4): 418-434. 10.1007/s00239-002-2413-2.

Yellen G: The voltage-gated potassium channels and their relatives. Nature. 2002, 419 (6902): 35-42. 10.1038/nature00978.

Long SB, Campbell EB, Mackinnon R: Crystal structure of a mammalian voltage-dependent Shaker family K + channel. Science. 2005, 309 (5736): 897-903. 10.1126/science.1116269.

Deeken R, Geiger D, Fromm J, Koroleva O, Ache P, Langenfeld-Heyser R, Sauer N, May ST, Hedrich R: Loss of the AKT2/3 potassium channel affects sugar loading into the phloem of Arabidopsis. Planta. 2002, 216 (2): 334-344. 10.1007/s00425-002-0895-1.

Zimmermann S, Sentenac H: Plant ion channels: from molecular structures to physiological functions. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1999, 2 (6): 477-482. 10.1016/S1369-5266(99)00020-5.

Dreyer I, Michard E, Lacombe B, Thibaud JB: A plant Shaker-like K + channel switches between two distinct gating modes resulting in either inward-rectifying or “leak” current. FEBS Lett. 2001, 505 (2): 233-239. 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02832-0.

Michard E, Dreyer I, Lacombe B, Sentenac H, Thibaud JB: Inward rectification of the AKT2 channel abolished by voltage-dependent phosphorylation. Plant J. 2005, 44 (5): 783-797. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02566.x.

Marten I, Hoth S, Deeken R, Ache P, Ketchum KA, Hoshi T, Hedrich R: AKT3, a phloem-localized K + channel, is blocked by protons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999, 96 (13): 7581-7586. 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7581.

Lacombe B, Pilot G, Michard E, Gaymard F, Sentenac H, Thibaud JB: A shaker-like K(+) channel with weak rectification is expressed in both source and sink phloem tissues of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2000, 12 (6): 837-851.

Cherel I, Michard E, Platet N, Mouline K, Alcon C, Sentenac H, Thibaud JB: Physical and functional interaction of the Arabidopsis K(+) channel AKT2 and phosphatase AtPP2CA. Plant Cell. 2002, 14 (5): 1133-1146. 10.1105/tpc.000943.

Fehr WR, Caviness CE, Burmood DT, Pennington JS: Stage of development descriptions for soybeans, Glycine Max (L.) Merrill1. Crop Sci. 1971, 11 (6): 929-931. 10.2135/cropsci1971.0011183X001100060051x.

Gajdanowicz P, Michard E, Sandmann M, Rocha M, Correa LG, Ramirez-Aguilar SJ, Gomez-Porras JL, Gonzalez W, Thibaud JB, van Dongen JT, Dreyer I: Potassium (K+) gradients serve as a mobile energy source in plant vascular tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011, 108 (2): 864-869. 10.1073/pnas.1009777108.

Matthews REF: Plant virology. 1991, San Diego, CA: Academic

Wang X, Wang Y, Tian J, Lim BL, Yan X, Liao H: Overexpressing AtPAP15 enhances phosphorus efficiency in soybean. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151 (1): 233-240. 10.1104/pp.109.138891.

Song ZY, Tian JL, Fu WZ, Li L, Lu LH, Zhou L, Shan ZH, Tang GX, Shou HX: Screening Chinese soybean genotypes for Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation suitability. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2013, 14 (4): 289-298. 10.1631/jzus.B1200278.

Saghai-Maroof MA, Soliman KM, Jorgensen RA, Allard RW: Ribosomal DNA spacer-length polymorphisms in barley: mendelian inheritance, chromosomal location, and population dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984, 81 (24): 8014-8018. 10.1073/pnas.81.24.8014.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Yuming Wang of Jilin Academy of Agricultural Sciences for providing the SMV-resistant genotype Rsmv1 and the SMV-susceptible genotype Ssmv1. This work was supported by the Ministry of Agriculture of China (2013ZX08004-001, 2013ZX08004-004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HS and BL conceived and designed the research. LZ, HH, RL, and QH conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. LZ and HS wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12870_2014_1573_MOESM1_ESM.pptx

Additional file 1: Figure S1: Sequence of GmAKT2 full-length cDNA. Figure S2. Amount of SMV RNA. Ten-day-old soybean plants in low-K soil with unrolled unifoliate leaves were mechanically inoculated with SMV G7, G3 or buffer (Mock). Soybean trifoliate leaves were sampled at 14 and 28 DAI to extract total RNA for qRT-PCR analysis of SMV. Transcript levels were calculated using the formula 2-ΔCt for the expression levels relative to GmACTIN. Data represent means of four biological replicates with error bars indicating SD. Figure S3. Phylogenetic analysis of soybean and Arabidopsis Shaker family proteins. This tree was obtained using the whole alignment and distance method. GmAKT2 and AtAKT2 formed a separate branch. The bar indicates the mean distance of 0.1 changes per amino acid residue. (PPTX 168 KB)

12870_2014_1573_MOESM2_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 2: Table S1: Sequences of primer pairs used for RT-PCR with the accession numbers of the genes. (XLSX 12 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, L., He, H., Liu, R. et al. Overexpression of GmAKT2potassium channel enhances resistance to soybean mosaic virus. BMC Plant Biol 14, 154 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-14-154

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-14-154