Abstract

Background

Camptothecin is a plant alkaloid that specifically binds topoisomerase I, inhibiting its activity and inducing double stranded breaks in DNA, activating the cell responses to DNA damage and, in response to severe treatments, triggering cell death.

Results

Comparative transcriptomic and proteomic analyses of maize embryos that had been exposed to camptothecin were conducted. Under the conditions used in this study, camptothecin did not induce extensive degradation in the genomic DNA but induced the transcription of genes involved in DNA repair and repressed genes involved in cell division. Camptothecin also affected the accumulation of several proteins involved in the stress response and induced the activity of certain calcium-dependent nucleases. We also detected changes in the expression and accumulation of different genes and proteins involved in post-translational regulatory processes.

Conclusions

This study identified several genes and proteins that participate in DNA damage responses in plants. Some of them may be involved in general responses to stress, but others are candidate genes for specific involvement in DNA repair. Our results open a number of new avenues for researching and improving plant resistance to DNA injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Maintenance of genome stability is of critical importance for all organisms. Genomic DNA is continuously subject to many types of damage resulting from endogenous factors (production of reactive oxygen species, stalled replication forks, etc.) or the action of exogenous agents (radiation, naturally occurring radioisotopes, chemical mutagens such as heavy metals, etc.) [1]. Double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) are one of the most serious forms of DNA damage, potentially causing chromosomal translocations and rearrangements [2]. In response to DSBs, cells initiate complex signalling pathways that activate DNA repair, cell-cycle arrest, and eventually cell death [3]. DSBs repair is mediated by two basic mechanisms: homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) [4]. In HR, an intact copy of the damaged region (a sister chromatid, for example) acts as a template to repair the break. In NHEJ, DSBs are simply rejoined largely independently of the DNA sequence. Bacteria and yeast usually employ HR whereas mammals and plants usually use NHEJ.

In addition to the direct repair of DNA breaks, additional responses are activated during DNA-damage stress. For example, DNA damage in plant cells usually induces the accumulation of signal transduction intermediates such as nitric oxide, ROS or ethylene [5, 6] and produces changes in the cytosolic-free Ca2+ [7]. It also induces cell cycle arrest, the inhibition of DNA and RNA synthesis, and a rapid protein turnover via the proteasome [8, 9]. Additional reported effects are a reduction in the photosynthesis-related proteins [10], the accumulation of protective proteins such as pathogenesis-related protein-1 [11], the accumulation of protecting pigments [12], an increase in the expression of senescence- and cell death-associated genes [13] and the activation of different cellular detoxification mechanisms [14]. The regulation of all these responses is complex and involves different levels of regulation, including the modulation of transcriptional activity [15], post-transcriptional mechanisms (RNA processing, RNA silencing, etc.) [16–18] and post-translational modifications (protein phosphorylation, ubiquitination, SUMOylation, etc.) [19]. These processes are based on signal transduction initiated by sensor proteins that recognise the damage in the DNA and activate the transducers, which send the signal to the effector proteins [20]. The network of transcriptional, post-transcriptional and post-translational modifications ensures temporally and spatially appropriate patterns of stress-responses.

DNA topoisomerase I (TOPI) regulates the topological state of DNA by cleaving and re-joining one DNA strand and allowing DNA relaxation [21]. TOPI activity is essential in dividing cells to release the torsion created by the progression of DNA replication forks. The presence of active TOPI is essential for embryo development in Drosophila and mouse [22]. In plants, TOPI plays a similar basic role and, for example, the disruption of the two TOPI encoding genes in Arabidopsis thaliana is lethal [23]. Camptothecin (CPT) is a plant alkaloid that specifically binds TOPI, stabilising the complexes formed between DNA and TOPI [24]. The collisions between the trapped TOPI-CPT complexes and the replication fork during DNA replication produce DSBs which induce DNA damage responses [25]. In consequence, actively dividing cells are much more sensitive to CPT than non-dividing cells, a property that has been exploited in the treatment of cancer [24]. However, non-dividing cells are also sensitive to CPT as collisions of the RNA polymerase machinery with the TOPI-CPT complexes, although less frequent, are also able to produce DSBs [26]. CPT-mediated TOPI-DNA complexes can be degraded via the 26S proteasome pathway so, at low CPT concentrations, cells can survive [27]. However, in actively dividing cells the high number of collisions may exceed the capacity of the cells to eliminate TOPI-DNA complexes and the DNA repair capability of the cells and, under these circumstances, cell death is initiated. CPT has a similar effect on TOPI in plant and animals. For example, CPT inhibits, in vitro, the activity of TOPI extracted from maize immature embryos [28], produces the abortion of shoots and roots in Arabidopsis [23], and induces cell death in tomato cell cultures [29].

In this study, we profiled proteins and genes whose expression is changed in immature maize embryos as a consequence of the DNA damage produced by CPT. Immature embryos contain a high proportion of actively dividing cells and, in consequence, are particularly sensitive to CPT. The combination of microarray and two-dimensional gel electrophoresis protein analysis allowed us to identify molecular events that are regulated during DNA repair responses in plants at different levels: transcriptional, post-transcriptional, translational and post-translational. We identified candidate genes and proteins which may be specifically involved in the DNA repair responses.

Results

Camptothecin induces DNA damage responses in maize immature embryos but not an extensive cell death process

Maize caryopses were collected 15 days after pollination and their dissected embryos incubated, in the dark, in culture medium with or without 50 μM camptothecin (CPT). After 8 days of culture, the germination rates of treated and untreated embryos were not significantly different (24% ± 5 in control and 20% ± 6 in treated embryos) and their morphological characteristics were similar.

CPT is a DNA damaging agent that induces DNA repair responses [24], while ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) is an enzyme that provides dNTPs for DNA repair, with RNR genes being induced in response to DNA damage [30]. In order to check if, under our conditions, CPT is able to induce DNA repair responses in maize embryos, we used a maize gene ZmRNR2 probe encoding the ribonucleotide reductase, in northern blot hybridization (Figure 1A and 1B). There was a high level of accumulation of the ZmRNR2 mRNA after 3 days of CPT treatment and, although reduced, the accumulation was maintained after 8 days of treatment (Figure 1A). The induction of ZmRNR2 was much higher in the embryo axis than in the scutellum (Figure 1B).

CPT-induced DNA damage analysis. (A) Northern blot of ZmRNR2 gene of immature maize embryos treated with 50 μM CPT for three (E3D) and eight (E8D) days. (B) Northern blot of ZmRNR2 gene of dissected embryo axis (EA) and scutellum (SC) of immature maize embryos treated with 50 μM CPT for three days. (C) In-gel nuclease activity assay of total protein extracts (10 μg) of immature maize embryos treated with 50 μM CPT for three (E3D) and eight (E8D) days. The nuclease activity is detected as a non-stained halo in a polyacrylamide gel containing DNA stained with ethidium bromide. The deduced weight of the proteins with nuclease activity is indicated on the left (kDa). (D) In-gel nuclease activity assay of total protein extracts (10 μg) of dissected embryo axis (EA) and scutellum (SC) of immature maize embryos treated with 50 μM CPT for three days. The deduced weights of the proteins with nuclease activity are indicated on the left (kDa). (E) Integrity of nuclear DNA (4 μg) of immature maize embryos treated with 50 μM CPT for three (E3D) and eight (E8D) days, assayed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels. (F) Integrity of nuclear DNA (4 μg) of dissected embryo axis (EA) and scutellum (SC) of immature maize embryos treated with 50 μM CPT for three days, assayed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels.

Nucleases are involved in DNA damage responses [31] and in cell death [32]. In plants, cell death-related nucleases have been classified according to their cationic cofactors, as Ca2+ or Zn2+-dependent [33]. The ability of CPT to induce nuclease activities in maize embryos was tested using in-gel nuclease activity assays (Figure 1C and 1D). An increase in the activity of a Ca2+-dependent nuclease of about 32 kDa was clearly evident after 3 days of CPT treatment using an assay buffer containing 1 mM CaCl2, being only slightly reduced after 8 days of treatment (Figure 1C), and was higher in the embryo axis compared to scutellum (Figure 1D). In contrast, no zinc-dependent nuclease activity was detected using 1, 2 or 5 mM Zn2+ (results not shown).

The CPT-induced Ca2+-dependent nuclease could be involved in DNA repair but also in programmed cell death (PCD). PCD is usually characterised by inter-nucleosomal genomic DNA fragmentation, producing, after gel electrophoresis, a characteristic DNA ladder pattern [34]. The results of electrophoresis of genomic DNA extracted from treated embryos was not significantly different to that observed with untreated embryos, showing a certain DNA ladder (Figure 1E). The same analyses using DNA extracted separately from embryo axis and scutellum clearly show that the DNA ladder was only present in the scutellum sample (Figure 1F). Degradation in genomic DNA extracted from scutellum has been previously observed in maize [34]. Cells in the scutellum close to the embryo axis undergo PCD as a normal part of seed development and this may explain the observed DNA ladder [35]. Exposure to 50 μM CPT did not, however, produce a significant change in the DNA integrity in the embryo axis or scutellum. This suggests that the CPT-induced Ca2+-dependent nuclease is involved in DNA repair and not in cell death.

In situ detection of fragmented DNA (TUNEL), as a sensitive technique to detect the initial steps of genomic DNA degradation, was used to analyse the effects of CPT on maize embryo DNA integrity (Figure 2). In accordance with published data [35], untreated embryos only showed TUNEL positive nuclei in the scutellum, close to the embryo axis (Figures 2A and 2C). There was no increase in the number of positive nuclei in the scutellum of CPT treated embryos (Figure 2B and 2D). The embryo axis of untreated embryos did not show any TUNEL staining (Figure 2E). On the contrary, in CPT-treated embryos, some cells in the embryo axis showed TUNEL stained nuclei (Figure 2F). However, the proportion of cells with stained nuclei was not high, which may explain why we did not observe extensive genomic DNA degradation in gel electrophoresis.

In situ detection of DNA fragmentation in histological sections of immature embryos treated with CPT. TUNEL assay on histological sections of untreated embryos (a, c, and e) and embryos treated with 50 μM CPT for 3 days (b, d and f). The TdT enzyme was omitted in the negative control (g), and the positive control included a DNaseI incubation (h). Arrows indicate stained nuclei. SC, scutellum. EA, embryo axes. C, coleoptile. LP, leaf primordium. R, radicle. Scale bars: = 100 μm.

These results indicate that, under the conditions used here, CPT induced DNA repair responses in maize embryos but not an extensive cell death process.

Transcriptional responses to CPT-induced DNA damage

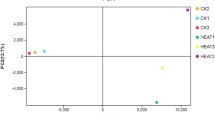

A global picture of the changes in gene expression produced during CPT treatment was obtained using the Affymetrix™ GeneChip Maize Genome Array. In this experiment, control and 3-day CPT-treated embryos were compared (Figure 3). Ninety-three probe sets were found to have significantly increased or decreased signal in response to CPT, 39 up-regulated (Table 1) and 54 down-regulated (Table 2). The probe set corresponding to the ZmRNR2 gene, previously used as a control for DNA damage response, was among the up-regulated genes. A quantitative real-time RT-PCR approach was used to validate the expression of 10 genes identified as differentially expressed in the microarray analysis, including 7 up- and 3 down-regulated genes (Figure 4). Real-time PCR results were in very good agreement with the microarray data, although there were higher fold-changes using real time RT-PCR, which may be due to differences in the dynamic range and sensitivity of the two methods, as has been previously suggested [36].

Quantitative real time RT-PCR analysis of microarray results. Real time RT-PCR of seven up-regulated and three down-regulated genes in response to camptothecin treatment. Relative expression values were normalised using actin as housekeeping gene. Induction values obtained in the microarray hybridization are indicated for each gene (*). The fold-change expression were calculated from three independent biological replicates; the biological replicates and standard errors are indicated (error bars). PDI (protein disulfide isomerase, U90944), HRGP (hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein, BM073956), LRR (leucine rich repeats protein, CK370970), RNR1 (ribonucleotide reductase large subunit, BM079174), TBPIP1 (TBP-1 interacting protein, CA827618), RAD51B (AF079429) XRI-1 (X-ray induced gene 1, AY108750), CycB1 (cyclin IaZm, AI622454), B3 (B3 domain containing DNA binding protein, CO531505), E98 (HMG1/2 family transcription factor, AY104178).

The molecular roles of many of the altered genes remain unknown (31% of the up-regulated and 44% of the down-regulated). These genes may be involved in the control and/or execution of DNA damage responses (Figure 5). DNA replication, recombination and repair (18%) and defense and stress responses (15%) were the two most abundant functional categories among the up-regulated genes. Among down-regulated genes, the two most abundantly represented categories were signal transduction and gene expression (22%) and cell growth and division (17%). The functional category of DNA replication, recombination and repair was significantly more represented among the induced genes while the cell growth and division category was significantly more represented among the repressed genes (Figure 5).

Functional categories of differentially expressed genes. Functional categories of the camptothecin induced (grey bars) and repressed (black bars) genes identified by microarray analysis. The functional categories significantly overrepresented between the induced or repressed genes are indicated by an asterisk (Fisher's Exact Test, p ≤ 0.05).

CPT treatment induced the expression of genes involved in DNA repair and DNA damage responses as, for example:

- Two subunits of the ribonucleotide reductase: involved in the DNA repair processes [30].

- RAD51: encodes a protein required for meiosis and HR repair [37]. Maize mutants in two RAD51 maize genes are hypersensitive to radiation [38]. The Arabidopsis gene AtRAD51a is transcriptionally up-regulated by DSB-inducing agents and seems to be required for HR repair after bleomycin treatment [39].

- Rpa2: encodes a protein that is part of a heterotrimeric protein complex that specifically binds single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and plays multiple roles in DNA metabolism, including DNA repair and recombination [40]. RPA genes are transcriptionally induced in Aspergillus nidulans exposed to CPT [41].

- TBPIP1: encodes a protein involved in chromosome pairing and segregation [42]. In humans, TBPIP1 enhances the strand exchange mediated by RAD51 [43]. In Arabidopsis, the TBPIP1 gene is transcriptionally induced by DNA damage [44].

- XRI-1: encodes a protein essential for meiosis and that plays a role during HR in Arabidopsis [45]. This gene is highly and rapidly transcriptionally induced by X-ray radiation and is also highly induced by other DSBs-inducer agents [44]. The encoded protein is probably part of the meiotic recombination complex MND1/AHP2, which collaborates with RAD51 in the DNA strand invasion during recombination [46].

- Acetyltransferase, GNAT family protein: some yeast GNAT family members are involved in DSBs repair [47].

- Rph16: encodes a protein similar to RAD16 and is involved in the nucleotide excision repair of UV damage [48].

CPT treatment repressed the expression of genes involved in cell cycle, cell division and cell growth (Table 2). For example:

- Three cyclins: IaZm, IIZm and IIIZm.

- Shugosin-1: encodes a protein involved in the maintenance of centromeric cohesion of sister chromatids during meiosis and mitosis. Depletion of the human Sgo1 gene produces mitotic cell cycle arrest [49].

- TPX2: encodes a protein necessary for mitotic fuse formation in vertebrates [50]. The inhibition of the Arabidopsis TPX2 gene blocks mitosis [51].

- Knolle: encodes a syntaxin-like protein that acts during cytokinesis vesicle fusion and mediates cell-plate formation [52]. Knolle expression is repressed by gamma radiation in Arabidopsis [15].

- Patellin-5: patellins are involved in vesicle trafficking events. The Arabidopsis patellin PATL1 has been associated with the formation of the cell-plate during cytokinesis [53].

- Knotted1 (Kn1): encodes a homeo-domain protein involved in the regulation of leaf cell development [54].

- Microtubule-associated protein RP/EB family member 3: encodes a protein that binds to the end of the microtubules and is important in maintaining the structure of the mitotic spindle [55].

- Growth regulating factor 8-like: encodes a protein involved in leaf and cotyledon growth in Arabidopsis [56].

- Rough sheath1: encodes a protein involved in cell differentiation [57].

- Frizzy-like protein/WD-repeat cell cycle regulatory protein: encodes a protein similar to the tomato CCS52B that probably is involved in cell-cycle control during mitosis [58].

Alterations in maize embryo proteome in response to CPT

Equal amounts of total protein extracted from control and from CPT-treated maize embryos were fractionated using 2-D gel electrophoresis (Figure 6A and 6B). At least three-fold increase/decrease and t-test p < 0.05 were used as the criteria to select differentially accumulated polypeptides. In response to CPT treatment, 455 spots showed quantitative or qualitative (presence/absence) variations between the two gels, with the intensity decreasing in 169 and increasing in 286. Some examples of up- or down-accumulated spots are shown in figure 6C. Forty-three of the spots with significant differential expression on gels were chosen for identification by MS/MS mass spectrometry. Interpretable MS/MS spectra were obtained for 31 spots. The location of these in the gels is shown in Figures 6A and 6B.

Comparative proteomic analysis of CPT-induced DNA damage in maize immature embryos. 2-D gel electrophoresis of untreated (A) and camptothecin-treated (B) maize embryos showing the localisation of the spots identified by mass spectrometry. The pH gradient, 3 to 11, is indicated on the top axis and molecular masses on the left. Spots that were excised and identified by mass spectrometry are labeled with spot ID numbers [U1-16, spots up-accumulated by CPT treatment; D1-14, spots down-accumulated by CPT treatment] listed in Table 3. (C) Portions of 2-D gels showing spots (arrows) that were differentially abundant between untreated (CON) and treated (CPT) embryos.

The identified proteins belong to a variety of functional categories (Table 3). For example, CPT alters the accumulation of two enzymes involved in glycolytic metabolism: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and triosephosphate isomerase 1. Interestingly, in human neuronal cells, CPT also produces changes in the accumulation of GAPDH [59]. In plants, the accumulation of both proteins has been described in response to different types of stress [60–64].

Some of the identified proteins are involved in antioxidant responses. Antioxidant activity protects against ROS accumulation, which can be produced by a variety of stresses, including DNA damage [65]. In mammals, CPT induces the accumulation of antioxidant enzymes in the nucleus [66]. The accumulation of two proteins involved in pathogenesis responses, PR1 and Betv1, was observed in response to CPT. They are also induced by abiotic stresses such as heavy metals [67] and UV radiation [68].

The accumulation of at least two 26s proteasome regulatory subunits is altered in response to CPT, one increased and the other reduced. Interestingly, CPT-TOPI-DNA complexes may be degraded by the ubiquitin-dependent pathway [27].

We observed changes in the accumulation of several proteins involved in RNA metabolism or RNA binding proteins:

- RraA: an RNaseE inhibitor which may be involved in the degradosome complex in E. coli [69, 70]. Regulation of RraA by DNA damage stress could be related to changes in the regulation of RNA homeostasis.

- DEAD-family RNA helicase: DEAD-RNA helicases act in RNA metabolism promoting either RNA synthesis or decay [71]. Some have been associated with abiotic stress [72].

- Glycine-rich RNA-binding protein 8: some glycine-rich RBPs in Arabidopsis (GR-RBPs) are significantly induced by cold, drought and salinity, whereas others are repressed by other sources of stresses [73].

- RNA recognition motif-containing (RRM) protein: RRM-containing proteins are involved in most post-transcriptional gene expression processes (i.e. mRNA and rRNA processing, RNA export and stability) [74].

We also observed an increase in the accumulation of two spots corresponding to eukaryotic elongation factors. Experiments in yeast and mammals demonstrate that translation initiation factor 5A (eIF5A) is actually involved in mRNA nucleus-cytoplasm export and not translation, specifically regulating genes involved in cell growth and proliferation, and in cell death [75]. In Arabidopsis, AteIF5A/AtFBR12 (At1g26630) promotes PCD associated with the hypersensitive pathogen response [76], and AteIEF5A-1 (At1g13950) has been associated with PCD during xylogenesis [77]. Thus, regulation of eiF5A by CPT suggests it is involved in cell cycle and PCD regulation.

Lack of correlation between CPT-induced changes in protein abundance and changes in mRNA accumulation

This study provided data on the most differentially expressed genes in control and CPT-treated embryos, and the most differentially accumulated proteins, allowing us to compare the datasets. The genes encoding 24 of the 31 identified proteins are represented in the microarray, but there was no significant change in expression in response to CPT (Table 4). This was confirmed by northern blot hybridizations using probes corresponding to nine of these genes, with no significant differences in the hybridization intensities observed (Figure 7).

Northern blot analysis of genes encoding proteins identified by comparative proteomic analysis. Northern blot analysis (20 μg of total RNA per sample) showing expression of nine selected genes coding for proteins identified by comparative proteomic analysis in immature maize embryos treated with camptothecin 50 μM: glycine-rich RNA-binding protein 8, EU963577; pathogenesis-related protein 1, AY103811; ascorbate peroxidase 1, NM_001112030; eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A, AY103556; guanine nucleotide-binding protein beta subunit-like, EU952736; glutathione S-transferase 19, AF244684; 26S proteasome non-ATPase subunit 4, BT018579; putative RNA-binding protein (RRM superfamily), BT065318; triosephosphate isomerase 1, AY103629]. Hybridization of the 18S ribosomal RNA was used as loading control. The corresponding protein spot ID and the relative fold-change (CPT/CON) normalised by 18S rRNA are indicated.

Discussion

Our aim was to identify new elements involved in cellular responses to genomic damage in plants, using CPT as a toxic agent and applying transcriptomic and proteomic approaches to identify the genes, proteins and cellular mechanisms involved. We identified a series of genes and proteins whose expression/accumulation significantly change in response to CPT, although the identified genes do not correspond to the identified proteins. These differences may be a consequence of the different sensitivity of the methods. Moreover, the level of protein accumulation does not necessarily agree with the level of mRNA expression. This incongruent expression between mRNAs and proteins has been observed by other groups, in other species and experimental conditions [78–80] and is most likely a result of the biology of gene expression which includes various levels of regulation during protein synthesis: post-transcriptional, translational, and post-translational. Thus, integrated analysis of both mRNAs and proteins is crucial to gain further insights into complex biological systems.

The basic mechanism of action for CPT has been well-studied and characterised in animal cells [24]. CPT generates replication-mediated DSBs in DNA which in turn induce DNA repair, cell cycle arrest and, under certain circumstances, cell death. Under our conditions, CPT did not induce extensive cell death in maize embryos, as demonstrated by TUNEL staining which only appeared in some cells in the embryo axis after CPT-treatment. At the developmental stage analyzed here, cells in the scutellum divide at a very limited rate, but cells in the embryo axis divide rapidly. This difference may explain the higher sensitivity to CPT of the cells in the embryo axis.

Two basic mechanisms of DSBs DNA repair have been described: homologous recombination and non-homologous end joining [4]. Our transcriptomic analysis identified the induction of some genes already known to be involved in DNA repair. Interestingly, most of them are involved in the HR repair pathway, suggesting that this is the main mechanism for DSBs repair in maize embryos, at least in response to CPT. CPT also produces an increase of a 32 kDa calcium-dependent nuclease activity. However, this nuclease is unlikely to be involved in the extensive fragmentation of the genomic DNA observed in different cell death processes as extensive DNA fragmentation was not observed. Nucleases are also involved in most DNA repair mechanisms, including HR [81]. These data suggests that the 32 kDa nuclease activity observed may be involved in the DNA repair process.

CPT induces reversible or permanent cell-cycle arrest in G2-M phase in human and other cells [82] and produces major alterations in the expression of cell-cycle regulatory genes [83]. We found that CPT reduces the expression of several mitosis-related genes. In addition, we observed a reduction in the accumulation of the histone H2B involved in the structure of chromatin, and changes in the accumulation of two eukaryotic translation initiation factors which seem to also be involved in the cell-cycle process [84]. These results suggest that, in maize embryos, one of the cellular responses to CPT is the arrest of cell division.

In addition to more specific processes, DNA damage induces general stress mechanisms in maize embryos. For example, we observed changes in the expression and accumulation of proteins involved in ROS processing (glutathione S-transferase, Class III peroxidase precursor, chloroplast Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase, cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase), enzymes involved in glycolic metabolism (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, triosephosphate isomerase 1) and in pathogen responses (pathogenesis-related protein1 and Bet v I allergen). Pathogen resistance is increased after DNA damage induction, indicating a cross-link in DNA damage (and maybe other abiotic stresses) and defense responses [85].

An increasing number of studies combining proteomics and transcriptomics clearly demonstrate that mRNA and protein accumulation are not always correlated [86–88]. For instance, in yeast 73% of the variance in protein abundance is explained by the translation mechanism and only 27% due to variations in mRNA concentration [89]. Protein abundance is influenced by several factors at the post-transcriptional, translational, and post-translational levels. For example, there is a time lag between transcription and translation in which introns are excised and the transcripts are moved from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, and translation rates may be influenced by ribosome, tRNA and amino acids availability, codon usage or accessory protein binding association [90]. In addition, protein abundance is also influenced by post-translational processes such as glycosylation, phosphorylation and proteolytic processing.

Our proteome analysis indicated differences in the abundance (up and down) of the encoded proteins of 24 genes whose mRNA levels do not significantly change in response to CPT (Table 4). It is possible that CPT induces the transcription of some genes only during the first hours of treatment, and after three days of treatment the mRNA levels are similar to the control but the abundance of the encoded protein is higher. Differences in the translation rate may also explain the lack of correlation. In animals, post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression during the stress response means specific stress-induced transcripts receive the highest transcriptional priority [91]. Interestingly, some of the spots identified in the proteomic analysis correspond to proteins associated with RNA metabolism and RNA binding proteins, and may be involved in the regulation of mRNA translation.

Many post-translational processes affect the position of a protein in 2D gels such that the protein appears as differentially accumulated in a proteomic analysis. We have identified changes in genes and proteins involved in protein modification and post-translational regulation. For example, the accumulation of at least two 26s proteasome regulatory subunits is altered in response to CPT and the expression of the proteasome inhibitor-like protein PI31 is increased. Ubiquitin/proteasome-mediated protein degradation plays a central role in the regulation of several aspects of plant development and stress responses [92] and our data indicate that it may also be involved in regulating DNA damage responses. In fact, there are evidences that CPT-TOPI-DNA complexes may be degraded by the ubiquitin-dependent pathway in mammals and yeast [27, 93]. Our data suggest that a similar situation may occur in plants. Moreover, the expression of embryonic flower 2 is repressed, a gene encoding a protein homologous to Drosophila Polycomb genes which mediate the epigenetic control of homeotic gene expression [94].

The role of several of the genes identified in the transcriptomic analysis is unknown. These genes may play a role in DNA damage detection and repair mechanisms, especially those genes that are only induced in response to genomic damage and not in response to other types of stress. Unfortunately the data currently available in maize does not allow us to determine which of them are specifically induced by DNA damage, but many of the maize identified genes have clear homologues in Arabidopsis (Table 1 and 2). Microarray analyses in Arabidopsis have been used to study the effects of several abiotic stresses, including two DNA damage agents, bleomycin [4] and gamma radiation [15]. Examining microarray databases [95] we identified eight Arabidopsis genes homologous to maize CPT-induced genes and exclusively induced by DNA damage: At5g02220, of unknown function; At1g13330, encoding TBP-1 tat binding protein; At5g48720, encoding an X-ray induced gene required for post-meiotic stages of pollen development and for male and female meiosis; At3g27060 and At2g21790, encoding the ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) small and large subunit, respectively; At5g20850, encoding AtRAD51; and two genes, At5g18270 and At3g04060, encoding NAC transcriptions factors. NAC proteins constitute one of the largest families of plant-specific transcription factors, and the family is present in a wide range of land plants [96]. These two NAC proteins are interesting candidates for a regulatory role in DNA damage responses in plants.

Conclusions

The integration of microarray and proteomic analyses provides new data on DNA damage responses in plants. This is a complex process involving DNA repair and arrest of cell-cycle, but also general stress responses. Post-translational processing and the regulation of mRNA translation seem to have an important role in DNA damage responses.

Methods

Plant material and treatments

Maize (Zea mays L cv W64A pure inbred line) was grown under controlled conditions (16 h light, 28°C). Immature embryos (15 days after pollination) were extracted in sterile conditions and placed on MS plates (4.4% (w/v) Murashige and Skoog medium, 0.8% (w/v) Gelrite) supplemented (or not) with 50 μM camptothecin (Sigma-Aldrich) and maintained in a growth chamber at 26°C in darkness.

Histological analysis

Embryos were collected, fixed in ethanol-formaldehyde-acetic acid (80:3.5:5) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by 1 week at 4°C, and then stored in 70% ethanol at 4°C. Fixed samples were embedded in paraplast, de-waxed with Histo-Clear II (National Diagnostic, UK), re-hydrated in an ethanol series and equilibrated in 0.02 M citric acid-0.16 M Na2HPO4, pH 7.0. TUNEL assays were done using the In Situ Cell Death Detection kit (Roche) according to the supplier's protocol for difficult tissues. In negative controls, the TdT enzyme was omitted, and the positive controls were treated with DNase I for 10 min. Experiments were repeated three times.

RNA extraction and quantification

Total RNA was isolated from frozen samples using the lithium chloride method. DNase digestion of contaminating DNA in the RNA samples was done using RNase-Free DNaseI. Final RNA purification was performed using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to standard protocols. RNA was quantified with a NanoDrop ND-100 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies). RNA quality was assessed with a 2100 Bioanalyzer from Agilent Technologies.

Affymetrix GeneChip hybridization/Microarray analysis

Gene expression was analyzed using the Affymetrix GeneChip® Maize Genome Array, which contains probe sets to interrogate 13,339 genes, performing four independent biological replicates. cDNA synthesis, probe labeling, array hybridization and data analysis were as described by Bannenberg and col. [97], in the Genomics Service of the Centro Nacional de Biotecnologia (CNB-CSIC, Madrid). Raw data and normalised data were deposited at the ArrayExpress data library (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/) under accession number E-MEXP-2702. Differential expression was considered following the p < 0.05 and 2.0 fold change as the criteria of significance. Functional categories of the genes were determined based on Gene Ontology data. We used the Fisher's Exact Test (p ≤ 0.05) and ANOVA (p ≤ 0.01) to determine the significant differences in the functional categories among up- and down-regulated genes.

Real time quantitative RT-PCR

To validate the expression changes found in the microarray experiments, transcript levels of the ten selected genes were quantified by the ABI Prism 7700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, U.S.A) as described by Mascarell-Creus and col. [98]. The oligonucleotides chosen to amplify the selected genes were designed using the Primer Express Software (Applied Biosystems) and are listed in table 5. The actin gene was used as the internal control.

In-gel Nuclease Activity Assay

Immature maize embryos were ground in liquid nitrogen and resuspended in extraction buffer (150 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 0.5 mM PMSF, 20 μM leupeptin). The homogenate was clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. In-gel nuclease activity was measured according to Thelen and Northcote [99] using 10 μg of protein in 12.5% SDS-PAGE containing 50 μg/mL of single-stranded calf thymus DNA (Sigma) and 50 μg/mL bovine fibrinogen (Sigma). After electrophoresis, gels were washed twice in 25% (v/v) isopropanol, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0 for 30 min and twice in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 for 30 min. Gels were incubated overnight at 37°C with gentle agitation in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 for Ca2+/Mg2+-dependent activity or in 25 mM NaAc/HAc pH 5.5, 1, 2 or 5 mM ZnSO4, for Zn2+-dependent activity. Nuclease activity was detected by staining the gel with 1 μg/mL (w/v) ethidium bromide for 15 min and observed under UV.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

Maize embryos were ground in liquid nitrogen and crude protein extracts were solubilised in 1.2 ml buffer 1 (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 4% Triton X-100, 18 mM Tris-HCl pH 8) in the presence of 53 u/ml DNase I, 4.9 u/ml RNaseA and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (1 mM PMSF, 50 μM leupeptin, 1 μM pepstatin, 10 μM E-64, 10 μg/ml aprotinin). After 20 min incubation at 4°C, DTT at a final concentration of 14 mM was added and samples were centrifuged 10 min at 35000 g at 4°C. 2-DE analysis was performed basically as previously described [100] using pH 3-11, 24 cm immobilised pH gradient (IPG) strips (Immobiline DryStrips, GE Healthcare) for the first dimension. The optimal parameters for spot detection were: smooth = 4, saliency = 1.0 and minimum area = 5. To evaluate protein expression differences among gels, relative spot volume (% Vol.) was used. Protein abundance variation was validated by Student's t-Test (p < 0.05).

In-gel digestion of proteins and MS and MS/MS spectra

Proteins were in-gel digested with trypsin and tryptic peptides were extracted and analyzed by MALDI-TOF/MS (4700 Proteomics Analyzer, Applied Biosystems) or LC-ESI-QTOF (Q-TOF Global, Micromass-Waters) mass spectrometers in the Proteomics Platform (PCB) of the University of Barcelona as previously described [100].

Abbreviations

- CPT:

-

camptothecin

- TOPI:

-

DNA topoisomerase I

- DSBs:

-

double strand breaks

- RNR:

-

ribonucleotide reductase

- PCD:

-

programmed cell death

- TUNEL:

-

in situ detection of fragmented DNA

- MS/MS:

-

tandem mass spectrometry

- FDR:

-

false discovery rate

- HR:

-

homologous recombination.

References

Britt AB: DNA Damage and Repair in Plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1996, 47: 75-100. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.75.

Rich T, Allen RL, Wyllie AH: Defying death after DNA damage. Nature. 2000, 407: 777-783. 10.1038/35037717.

Jackson SP: Sensing and repairing DNA double-strand breaks. Carcinogenesis. 2002, 23: 687-696. 10.1093/carcin/23.5.687.

West CE, Waterworth WM, Sunderland PA, Bray CM: Arabidopsis DNA double-strand break repair pathways. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004, 32: 964-966. 10.1042/BST0320964.

A.-H.-Mackerness S, John CF, Jordan B, Thomas B: Early signaling components in ultraviolet-B responses: distinct roles for different reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide. FEBS letters. 2001, 489: 237-242. 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02103-2.

A.-H.-Mackerness S, Surplus SL, Blake P, John CF, Buchanan-Wollaston V, Jordan BR, Thomas B: Ultraviolet-B-induced stress and changes in gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana: role of signalling pathways controlled by jasmonic acid, ethylene and reactive oxygen species. Plant, Cell & Environment. 1999, 22: 1413-1423. 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1999.00499.x.

Frohnmeyer H, Loyall L, Blatt MR, Grabov A: Millisecond UV-B irradiation evokes prolonged elevation of cytosolic-free Ca2+ and stimulates gene expression in transgenic parsley cell cultures. The Plant Journal. 1999, 20: 109-117. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00584.x.

Logemann E, Wu SC, Schroder J, Schmelzer E, Somssich IE, Hahlbrock K: Gene activation by UV light, fungal elicitor or fungal infection in Petroselinum crispum is correlated with repression of cell cycle-related genes. Plant J. 1995, 8: 865-876. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.8060865.x.

Molinier J, Oakeley EJ, Niederhauser O, Kovalchuk I, Hohn B: Dynamic response of plant genome to ultraviolet radiation and other genotoxic stresses. Mutat Res. 2005, 571: 235-247.

Desimone M, Wagner E, Johanningmeier U: Degradation of active-oxygen-modified ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase by chloroplastic proteases requires ATP-hydrolysis. Planta. 1998, 205: 459-466. 10.1007/s004250050344.

Surplus SL, Jordan BR, Murphy AM, Carr JP, Thomas B, Mackerness SAH: Ultraviolet-B-induced responses in Arabidopsis thaliana: role of salicylic acid and reactive oxygen species in the regulation of transcripts encoding photosynthetic and acidic pathogenesis-related proteins. Plant, Cell & Environment. 1998, 21: 685-694. 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1998.00325.x.

Kalbina I, Strid A: Supplementary ultraviolet-B irradiation reveals differences in stress responses between Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes. Plant, Cell & Environment. 2006, 29: 754-763. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01436.x.

John CF, Morris K, Jordan BR, Thomas B, A-H-Mackerness S: Ultraviolet-B exposure leads to up-regulation of senescence-associated genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2001, 52: 1367-1373. 10.1093/jexbot/52.359.1367.

Casati P, Walbot V: Rapid transcriptome responses of maize (Zea mays) to UV-B in irradiated and shielded tissues. Genome Biol. 2004, 5: R16-10.1186/gb-2004-5-3-r16.

Ricaud L, Proux C, Renou JP, Pichon O, Fochesato S, Ortet P, Montane MH: ATM-mediated transcriptional and developmental responses to gamma-rays in Arabidopsis. PLoS One. 2007, 2: e430-10.1371/journal.pone.0000430.

Anderson P, Kedersha N: Stressful initiations. J Cell Sci. 2002, 115: 3227-3234.

Mazzucotelli E, Mastrangelo AM, Crosatti C, Guerra D, Stanca AM, Cattivelli L: Abiotic stress response in plants: When post-transcriptional and post-translational regulations control transcription. Plant Science. 2008, 174: 420-431. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.02.005.

Pothof J, Verkaik NS, van IW, Wiemer EA, Ta VT, van der Horst GT, Jaspers NG, van Gent DC, Hoeijmakers JH, Persengiev SP: MicroRNA-mediated gene silencing modulates the UV-induced DNA-damage response. Embo J. 2009, 28: 2090-2099. 10.1038/emboj.2009.156.

Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Smogorzewska A, McDonald ER, Hurov KE, Luo J, Bakalarski CE, Zhao Z, Solimini N, Lerenthal Y, Shiloh Y, Gygi SP, Elledge SJ: ATM and ATR substrate analysis reveals extensive protein networks responsive to DNA damage. Science. 2007, 316: 1160-1166. 10.1126/science.1140321.

Cimprich KA, Cortez D: ATR: an essential regulator of genome integrity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008, 9: 616-627. 10.1038/nrm2450.

Champoux JJ: DNA topoisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001, 70: 369-413. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.369.

Lee MP, Brown SD, Chen A, Hsieh TS: DNA topoisomerase I is essential in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993, 90: 6656-6660. 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6656.

Takahashi T, Matsuhara S, Abe M, Komeda Y: Disruption of a DNA topoisomerase I gene affects morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2002, 14: 2085-2093. 10.1105/tpc.001925.

Pommier Y: Topoisomerase I inhibitors: camptothecins and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006, 6: 789-802. 10.1038/nrc1977.

Piret B, Piette J: Topoisomerase poisons activate the transcription factor NF-kappaB in ACH-2 and CEM cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996, 24: 4242-4248. 10.1093/nar/24.21.4242.

Mondal N, Zhang Y, Jonsson Z, Dhar SK, Kannapiran M, Parvin JD: Elongation by RNA polymerase II on chromatin templates requires topoisomerase activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31: 5016-5024. 10.1093/nar/gkg705.

Desai SD, Li TK, Rodriguez-Bauman A, Rubin EH, Liu LF: Ubiquitin/26S proteasome-mediated degradation of topoisomerase I as a resistance mechanism to camptothecin in tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2001, 61: 5926-5932.

Carballo M, Gine R, Santos M, Puigdomenech P: Characterization of topoisomerase I and II activities in nuclear extracts during callogenesis in immature embryos of Zea mays. Plant Mol Biol. 1991, 16: 59-70. 10.1007/BF00017917.

De Jong AJ, Hoeberichts FA, Yakimova ET, Maximova E, Woltering EJ: Chemical-induced apoptotic cell death in tomato cells: involvement of caspase-like proteases. Planta. 2000, 211: 656-662. 10.1007/s004250000341.

Roa H, Lang J, Culligan KM, Keller M, Holec S, Cognat V, Montane MH, Houlne G, Chaboute ME: Ribonucleotide reductase regulation in response to genotoxic stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151: 461-471. 10.1104/pp.109.140053.

Deng C, Brown JA, You D, Brown JM: Multiple endonucleases function to repair covalent topoisomerase I complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2005, 170: 591-600. 10.1534/genetics.104.028795.

Aleksandrushkina NI, Vanyushin BF: Endonucleases and Their Involvement in Plant Apoptosis. Russian Journal of Plant Physiology. 2009, 56: 291-305. 10.1134/S1021443709030017.

Sugiyama M, Ito J, Aoyagi S, Fukuda H: Endonucleases. Plant Mol Biol. 2000, 44: 387-397. 10.1023/A:1026504911786.

Giuliani C, Consonni G, Gavazzi G, Colombo M, Dolfini S: Programmed cell death during embryogenesis in maize. Ann Bot. 2002, 90: 287-292. 10.1093/aob/mcf173.

Bastida M, Graziano E, Roca R, Lopez I, Sanchez-Pons N, Puigdomenech P, Vicient CM: A maize defective-kernel mutant (longcell) characterized by tubular cells, severe morphological alterations and induction of cell death. Planta. 2006, 223: 755-768. 10.1007/s00425-005-0136-5.

Czechowski T, Bari RP, Stitt M, Scheible WR, Udvardi MK: Real-time RT-PCR profiling of over 1400 Arabidopsis transcription factors: unprecedented sensitivity reveals novel root- and shoot-specific genes. Plant J. 2004, 38: 366-379. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02051.x.

Markmann-Mulisch U, Wendeler E, Zobell O, Schween G, Steinbiss HH, Reiss B: Differential requirements for RAD51 in Physcomitrella patens and Arabidopsis thaliana development and DNA damage repair. Plant Cell. 2007, 19: 3080-3089. 10.1105/tpc.107.054049.

Li J, Harper LC, Golubovskaya I, Wang CR, Weber D, Meeley RB, McElver J, Bowen B, Cande WZ, Schnable PS: Functional analysis of maize RAD51 in meiosis and double-strand break repair. Genetics. 2007, 176: 1469-1482. 10.1534/genetics.106.062604.

Chen IP, Haehnel U, Altschmied L, Schubert I, Puchta H: The transcriptional response of Arabidopsis to genotoxic stress - a high-density colony array study (HDCA). Plant J. 2003, 35: 771-786. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01847.x.

Fanning E, Klimovich V, Nager AR: A dynamic model for replication protein A (RPA) function in DNA processing pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34: 4126-4137. 10.1093/nar/gkl550.

Malavazi I, Savoldi M, Di Mauro SM, Menck CF, Harris SD, Goldman MH, Goldman GH: Transcriptome analysis of Aspergillus nidulans exposed to camptothecin-induced DNA damage. Eukaryot Cell. 2006, 5: 1688-1704. 10.1128/EC.00167-06.

Schommer C, Beven A, Lawrenson T, Shaw P, Sablowski R: AHP2 is required for bivalent formation and for segregation of homologous chromosomes in Arabidopsis meiosis. Plant J. 2003, 36: 1-11. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01850.x.

Enomoto R, Kinebuchi T, Sato M, Yagi H, Kurumizaka H, Yokoyama S: Stimulation of DNA strand exchange by the human TBPIP/Hop2-Mnd1 complex. J Biol Chem. 2006, 281: 5575-5581.

Culligan KM, Robertson CE, Foreman J, Doerner P, Britt AB: ATR and ATM play both distinct and additive roles in response to ionizing radiation. Plant J. 2006, 48: 947-961. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02931.x.

Dean PJ, Siwiec T, Waterworth WM, Schlogelhofer P, Armstrong SJ, West CE: A novel ATM-dependent X-ray-inducible gene is essential for both plant meiosis and gametogenesis. Plant J. 2009, 58: 791-802. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03814.x.

Vignard J, Siwiec T, Chelysheva L, Vrielynck N, Gonord F, Armstrong SJ, Schlogelhofer P, Mercier R: The interplay of RecA-related proteins and the MND1-HOP2 complex during meiosis in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3: 1894-1906.

Carrozza MJ, Utley RT, Workman JL, Côté J: The diverse functions of histone acetyltransferase complexes. Trends Genet. 2003, 19: 321-329. 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00115-X. Review

Bang DD, Ketting R, de Ruijter M, Brandsma JA, Verhage RA, van de Putte P, Brouwer J: Cloning of Schizosaccharomyces pombe rph16+, a gene homologous to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD16 gene. Mutat Res. 1996, 364: 57-71.

Watanabe Y: Shugoshin: guardian spirit at the centromere. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005, 17: 590-595. 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.10.003.

Wittmann T, Wilm M, Karsenti E, Vernos I: TPX2, A novel xenopus MAP involved in spindle pole organization. J Cell Biol. 2000, 149: 1405-1418. 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1405.

Vos JW, Pieuchot L, Evrard JL, Janski N, Bergdoll M, de Ronde D, Perez LH, Sardon T, Vernos I, Schmit AC: The plant TPX2 protein regulates prospindle assembly before nuclear envelope breakdown. Plant Cell. 2008, 20: 2783-2797. 10.1105/tpc.107.056796.

Batoko H, Moore I: Plant cytokinesis: KNOLLE joins the club. Curr Biol. 2001, 11: R423-426. 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00251-2.

Peterman TK, Ohol YM, McReynolds LJ, Luna EJ: Patellin1, a novel Sec14-like protein, localizes to the cell plate and binds phosphoinositides. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136: 3080-3094. 10.1104/pp.104.045369.

Scofield S, Murray JA: KNOX gene function in plant stem cell niches. Plant Mol Biol. 2006, 60: 929-946. 10.1007/s11103-005-4478-y.

Wen Y, Eng CH, Schmoranzer J, Cabrera-Poch N, Morris EJ, Chen M, Wallar BJ, Alberts AS, Gundersen GG: EB1 and APC bind to mDia to stabilize microtubules downstream of Rho and promote cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2004, 6: 820-830. 10.1038/ncb1160.

Kim JH, Choi D, Kende H: The AtGRF family of putative transcription factors is involved in leaf and cotyledon growth in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2003, 36: 94-104. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01862.x.

Kessler S, Townsley B, Sinha N: L1 division and differentiation patterns influence shoot apical meristem maintenance. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141: 1349-1362. 10.1104/pp.105.076075.

Mathieu-Rivet E, Gévaudant F, Sicard A, Salar S, Do PT, Mouras A, Fernie AR, Gibon Y, Rothan C, Chevalier C, Hernould M: Functional analysis of the anaphase promoting complex activator CCS52A highlights the crucial role of endo-reduplication for fruit growth in tomato. Plant J. 2010, 62: 727-741. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04198.x.

Yu LR, Johnson MD, Conrads TP, Smith RD, Morrison RS, Veenstra TD: Proteome analysis of camptothecin-treated cortical neurons using isotope-coded affinity tags. Electrophoresis. 2002, 23: 1591-1598. 10.1002/1522-2683(200206)23:11<1591::AID-ELPS1591>3.0.CO;2-#.

Ahsan N, Lee DG, Lee KW, Alam I, Lee SH, Bahk JD, Lee BH: Glyphosate-induced oxidative stress in rice leaves revealed by proteomic approach. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2008, 46: 1062-1070. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.07.002.

Campo S, Carrascal M, Coca M, Abian J, San Segundo B: The defense response of germinating maize embryos against fungal infection: a proteomics approach. Proteomics. 2004, 4: 383-396. 10.1002/pmic.200300657.

Hancock JT, Henson D, Nyirenda M, Desikan R, Harrison J, Lewis M, Hughes J, Neill SJ: Proteomic identification of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase as an inhibitory target of hydrogen peroxide in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2005, 43: 828-835. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2005.07.012.

Riccardi F, Gazeau P, de Vienne D, Zivy M: Protein changes in response to progressive water deficit in maize. Quantitative variation and polypeptide identification. Plant Physiol. 1998, 117: 1253-1263. 10.1104/pp.117.4.1253.

Salekdeh GH, Siopongco J, Wade LJ, Ghareyazie B, Bennett J: Proteomic analysis of rice leaves during drought stress and recovery. Proteomics. 2002, 2: 1131-1145. 10.1002/1615-9861(200209)2:9<1131::AID-PROT1131>3.0.CO;2-1.

Gadjev I, Stone JM, Gechev TS: Programmed cell death in plants: new insights into redox regulation and the role of hydrogen peroxide. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2008, 270: 87-144.

Cohen AA, Geva-Zatorsky N, Eden E, Frenkel-Morgenstern M, Issaeva I, Sigal A, Milo R, Cohen-Saidon C, Liron Y, Kam Z, Cohen L, Danon T, Perzov N, Alon U: Dynamic proteomics of individual cancer cells in response to a drug. Science. 2008, 322: 1511-1516. 10.1126/science.1160165.

Didierjean L, Frendo P, Nasser W, Genot G, Marivet J, Burkard G: Heavy-metal-responsive genes in maize: identification and comparison of their expression upon various forms of abiotic stress. Planta. 1996, 199: 1-8.

Rakwal R, Agrawal GK, Yonekura M: Separation of proteins from stressed rice (Oryza sativa L.) leaf tissues by two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis: induction of pathogenesis-related and cellular protectant proteins by jasmonic acid, UV irradiation and copper chloride. Electrophoresis. 1999, 20: 3472-3478. 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991101)20:17<3472::AID-ELPS3472>3.0.CO;2-0.

Lee K, Zhan X, Gao J, Qiu J, Feng Y, Meganathan R, Cohen SN, Georgiou G: RraA. a protein inhibitor of RNase E activity that globally modulates RNA abundance in E. coli. Cell. 2003, 114: 623-634. 10.1016/j.cell.2003.08.003.

Yeom JH, Go H, Shin E, Kim HL, Han SH, Moore CJ, Bae J, Lee K: Inhibitory effects of RraA and RraB on RNAse E-related enzymes imply conserved functions in the regulated enzymatic cleavage of RNA. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2008, 285: 10-15. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01205.x.

Cordin O, Banroques J, Tanner NK, Linder P: The DEAD-box protein family of RNA helicases. Gene. 2006, 367: 17-37.

Vashisht AA, Tuteja N: Stress responsive DEAD-box helicases: a new pathway to engineer plant stress tolerance. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2006, 84: 150-160. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2006.02.010.

Lorkovic ZJ: Role of plant RNA-binding proteins in development, stress response and genome organization. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14: 229-236. 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.01.007.

Cléry A, Blatter M, Allain FHT: RNA recognition motifs: boring? Not quite. Curr Op Struc Biol. 2008, 18: 290-298. 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.002.

Thompson JE, Hopkins MT, Taylor C, Wang TW: Regulation of senescence by eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A: implications for plant growth and development. Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9: 174-179. 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.02.008.

Hopkins MT, Lampi Y, Wang TW, Liu Z, Thompson JE: Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A is involved in pathogen-induced cell death and development of disease symptoms in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148: 479-489. 10.1104/pp.108.118869.

Liu Z, Duguay J, Ma F, Wang TW, Tshin R, Hopkins MT, McNamara L, Thompson JE: Modulation of eIF5A1 expression alters xylem abundance in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot. 2008, 59: 939-950. 10.1093/jxb/ern017.

Gygi SP, Rochon Y, Franza BR, Aebersold R: Correlation between protein and mRNA abundance in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 1999, 19: 1720-1730.

Chen G, Gharib TG, Huang CC, Taylor JMG, Misek DE, Kardia SLR, Giordano TJ, Iannettoni MD, Orringer MB, Hanash SM, Beer DG: Discordant Protein and mRNA Expression in Lung Adenocarcinomas. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002, 1: 304-313. 10.1074/mcp.M200008-MCP200.

Tian Q, Stepaniants SB, Mao M, Weng L, Feetham MC, Doyle MJ, Yi EC, Dai H, Thorsson V, Eng J, Goodlett D, Berger JP, Gunter B, Linseley PS, Stoughton RB, Aebersold R, Collins SJ, Hanlon WA, Hood LE: Integrated Genomic and Proteomic Analyses of Gene Expression in Mammalian Cells. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2004, 3: 960-969. 10.1074/mcp.M400055-MCP200.

Marti TM, Fleck O: DNA repair nucleases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004, 61: 336-354. 10.1007/s00018-003-3223-4.

Tsao YP, D'Arpa P, Liu LF: The involvement of active DNA synthesis in camptothecin-induced G2 arrest: altered regulation of p34cdc2/cyclin B. Cancer Res. 1992, 52: 1823-1829.

Zhou Y, Gwadry FG, Reinhold WC, Miller LD, Smith LH, Scherf U, Liu ET, Kohn KW, Pommier Y, Weinstein JN: Transcriptional regulation of mitotic genes by camptothecin-induced DNA damage: microarray analysis of dose- and time-dependent effects. Cancer Res. 2002, 62: 1688-1695.

Zhou FF, Yan M, Guo GF, Wang F, Qiu HJ, Zheng FM, Zhang Y, Liu Q, Zhu XF, Xia LP: Knockdown of eIF4E suppresses cell growth and migration, enhances chemosensitivity and correlates with increase in Bax/Bcl-2 ratio in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Med Oncol. 2011.

Kunz BA, Cahill DM, Mohr PG, Osmond MJ, Vonarx EJ: Plant responses to UV radiation and links to pathogen resistance. Int Rev Cytol. 2006, 255: 1-40.

Hack CJ: Integrated transcriptome and proteome data: the challenges ahead. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic. 2004, 3: 212-219. 10.1093/bfgp/3.3.212.

Jiang Y, Yang B, Harris NS, Deyholos MK: Comparative proteomic analysis of NaCl stress-responsive proteins in Arabidopsis roots. J Exp Bot. 2007, 58: 3591-36007. 10.1093/jxb/erm207.

Yan SP, Zhang QY, Tang ZC, Su WA, Sun WN: Comparative proteomic analysis provides new insights into chilling stress responses in rice. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006, 5: 484-496.

Olivares-Hernández R, Bordel S, Nielsen J: Codon usage variability determines the correlation between proteome and transcriptome fold changes. BMC Syst Biol. 2011, 25: 33-

Cagas SE, Jain MR, Li H, Perlin DS: Profiling the Aspergillus fumigatus proteome in response to caspofungin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011, 55: 146-154. 10.1128/AAC.00884-10.

Anderson P, Kedersha N: RNA granules: post-transcriptional and epigenetic modulators of gene expression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009, 10: 430-436.

Smalle J, Vierstra RD: The ubiquitin 26S proteasome proteolytic pathway. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2004, 55: 555-590. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141801.

Lin CP, Ba Y, Lyu YL, Desai SD, Liu LF: A ubiquitin-proteasome pathway for the repair of topoisomerase I-DNA covalent complexes. J Biol Chem. 2008, 283: 21074-21083. 10.1074/jbc.M803493200.

Yoshida N, Yanai Y, Chen L, Kato Y, Hiratsuka J, Miwa T, Sung ZR, Takahashi S: EMBRYONIC FLOWER2, a novel polycomb group protein homolog, mediates shoot development and flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2001, 13: 2471-2481.

Goda H, Sasaki E, Akiyama K, Maruyama-Nakashita A, Nakabayashi K, Li W, Ogawa M, Yamauchi Y, Preston J, Aoki K, Kiba T, Takasuto S, Fujioka S, Asami T, Nakano T, Kato H, Mizuno T, Sakakibara H, Yamaguchi S, Nambara E, Kamiya Y, Takahashi H, Hirai MY, Sakurai T, Shinozaki K, Saito K, Yoshida S, Shimada Y: The AtGenExpress hormone and chemical treatment data set: experimental design, data evaluation, model data analysis and data access. Plant J. 2008, 55: 526-542. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03510.x.

Olsen AN, Ernst HA, Leggio LL, Skriver K: NAC transcription factors: structurally distinct, functionally diverse. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10: 79-87. 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.010.

Bannenberg G, Martinez M, Rodriguez MJ, Lopez MA, Ponce de Leon I, Hamberg M, Castresana C: Functional analysis of alpha-DOX2, an active alpha-dioxygenase critical for normal development in tomato plants. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151: 1421-1432. 10.1104/pp.109.145094.

Mascarell-Creus A, Canizares J, Vilarrasa-Blasi J, Mora-Garcia S, Blanca J, Gonzalez-Ibeas D, Saladie M, Roig C, Deleu W, Pico-Silvent B, Lopez-Bigas N, Aranda MA, Garcia-Mas J, Nuez F, Puigdomenech P, Cano-Delgado AI: An oligo-based microarray offers novel transcriptomic approaches for the analysis of pathogen resistance and fruit quality traits in melon (Cucumis melo L.). BMC Genomics. 2009, 10: 467-10.1186/1471-2164-10-467.

Thelen MP, Northcote DH: Identification and purification of a nuclease from Zinnia elegans L.: a potential molecular marker for xylogenesis. Planta. 1989, 179: 181-195. 10.1007/BF00393688.

Irar S, Brini F, Goday A, Masmoudi K, Pagès M: Proteomic analysis of wheat embryos with 2-DE and liquid-phase chromatography (ProteomeLab PF-2D) -- A wider perspective of the proteome. J Proteomics. 2010, 73: 1707-1721. 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.05.003.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants BIO2004-01577 and AGL2009-09151 from Plan Nacional de Investigación Científica y Técnica, by the Centre CONSOLIDER on Agrigenomics and by the Xarxa de Referencia en Biotecnologia of the Generalitat de Catalunya. NSP was supported by a grant from the CSIC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

NSP and CV designed and performed most of the experiments; NSP and SI performed the proteome experiments, SI analyzed the proteomics data. NG designed and analyzed the results of the qRT-PCR analyses. NSP and CV analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sánchez-Pons, N., Irar, S., García-Muniz, N. et al. Transcriptomic and proteomic profiling of maize embryos exposed to camptothecin. BMC Plant Biol 11, 91 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-11-91

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-11-91