Abstract

Background

Calcium (Ca2+) has recently been shown to selectively increase the activity of monoamine oxidase-A (MAO-A), a mitochondria-bound enzyme that generates peroxyradicals as a natural by-product of the deamination of neurotransmitters such as serotonin. It has also been suggested that increased intracellular free Ca2+ levels as well as MAO-A may be contributing to the oxidative stress associated with Alzheimer disease (AD).

Results

Incubation with Ca2+ selectively increases MAO-A enzymatic activity in protein extracts from mouse hippocampal HT-22 cell cultures. Treatment of HT-22 cultures with the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 also increases MAO-A activity, whereas overexpression of calbindin-D28K (CB-28K), a Ca2+-binding protein in brain that is greatly reduced in AD, decreases MAO-A activity. The effects of A23187 and CB-28K are both independent of any change in MAO-A protein or gene expression. The toxicity (via production of peroxyradicals and/or chromatin condensation) associated with either A23187 or the AD-related β-amyloid peptide, which also increases free intracellular Ca2+, is attenuated by MAO-A inhibition in HT-22 cells as well as in primary hippocampal cultures.

Conclusion

These data suggest that increases in intracellular Ca2+ availability could contribute to a MAO-A-mediated mechanism with a role in AD-related oxidative stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

MAO-A and MAO-B, two isoforms of monoamine oxidase (MAO), are expressed on the mitochondrial outer membrane. MAO-mediated neurodegeneration can result from the formation of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as a by-product of metabolism of aminergic neurotransmitters including serotonin and dopamine. If it is not detoxified by antioxidant systems such as glutathione peroxidase – one of the most abundant such systems in brain [1] – then H2O2 can be converted by iron-mediated Fenton reactions to hydroxyl radicals that can initiate lipid peroxidation and cell death. This is exacerbated when antioxidant systems are compromised, such as during aging [2]. The reduction in the efficacy of these systems may simply be aggravated in chronic disease states such as Alzheimer disease (AD)[3].

It has been demonstrated that inhibitors of MAO-B, such as l-deprenyl and, more recently, rasagiline, are effective in the management of early symptoms of Parkinson's disease in the clinic and in animal models [4–6] as well as in patients with mild AD-type dementia [4, 7]. Both MAO-B-positive astrocytes [8] and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [9] have been found in the vicinity of β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques. L-Deprenyl and rasagiline, however, may exert some of their effects independently of MAO-B as the neuroprotection mediated by these drugs is often associated with concentrations of the drug that are well below those required for inhibition of the enzyme [6], and has been associated with activation of Bcl-2 family members, interactions with the mitochondrial pore complex, and modulation of amyloid precursor protein cleavage [4].

MAO-A also plays a role in neuropsychiatric and behavioral disorders. The importance of this isoform is suggested by the aggressive phenotype seen in male mice deficient in MAO-A [10] and in males in a Dutch kindred bearing a spontaneous mutation (resulting in a premature stop) in the mao-A gene [11]. Similarly, maltreated children, whose genotype confers low levels of MAO-A expression, more often develop conduct disorder, antisocial personality and adult violent crime than do children with a high-activity MAO-A genotype [12]. Relatively modest changes in MAO-A activity/function can have important neuropsychiatric consequences as demonstrated by the fact that [11C]-harmine-labeled MAO-A is elevated by only 34% throughout the brain of untreated depressed patients compared to controls, yet it appears to be the major contributor to monoamine metabolism in these same patients [13]. Depression not only may promote cognitive impairment, but also may be a risk factor for AD [14]. Not surprisingly, MAO-A, which is often targeted for the treatment of depression, is also a potential risk factor for late-onset AD [15–18]. In contrast to irreversible inhibitors of MAO-A such as clorgyline, reversible inhibitors such as moclobemide are better tolerated and have been particularly efficacious in treating depression [19, 20] and cognitive disorders [21] in the elderly. In addition, they protect against apoptosis [22] and glutamate-induced excitotoxicity [23]in vitro. Inhibition of MAO-A activity protects against striatal damage produced by the mitochondrial poison malonate and appears to rely on attenuation of dopamine-derived ROS [24], while apoptosis following serum starvation is reduced in MAO-A deficient cortical brain cells [25].

The NMDA-subtype of glutamate receptor has been linked to massive increases in mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation [26]. It is interesting that activation of this same receptor has been linked to Ca2+-dependent processes and pathology in [hepatic] encephalopathic brains [27] that correlates with a selective increase in MAO-A activity [28]. The selectivity of Ca2+ for MAO-A is demonstrated ex vivo using brains from monkey [29], mouse [30] and rat [31], and is supported by the ability of the Ca2+-channel antagonist nimodipine to block the selective increase in MAO-A activity observed in senescence-accelerated mouse brain [32]. Additional cations able to influence MAO-A function include Zn2+, which inhibits MAO-A activity [29], and Al3+ (another ion often linked to AD-like pathology), which activates it [33].

These combined observations, in addition to the fact that cytoplasmic free Ca2+ is elevated in aged neurons and even more so during neurodegeneration, such as that encountered during in AD [15, 34–36], certainly argue for examination of the relation between Ca2+ and MAO.

Methods

Antibodies and reagents

5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), β-phenylethylamine (PEA), the β-actin antibody and protease inhibitor cocktail were bought from Sigma-Aldrich Co. [14C]-5-HT (NEC-225) and [14C]-PEA (NEC-502) were purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. The MAO-A and CB-28K antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. IgG-HRP conjugates were obtained from Cedarlane Laboratories. All other reagents were purchased commercially.

Immortalized hippocampal cell cultures

The immortalized mouse hippocampal HT-22 cell line [20] was kindly provided by Dr. P. Maher (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA). Cells were cultured (5% CO2 at 37°C) in DMEM/low glucose medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/mL penicillin G sodium salt and 0.03% glutamine.

Monoamine oxidase (MAO) activity

MAOA and -B activities (nmol/hr/mg protein) in HT-22 cell cultures were estimated radiochemically [37]. Briefly, samples were homogenized in 80 volumes of oxygenated potassium phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 7.8) and incubated (100 μg/100 μl) for 10 min at 37°C with either 250 μM [14C]-5-HT (for MAO-A activity) or 50 μM [14C]-β-PEA (for MAO-B activity). The incubation was terminated by acidification and the labeled metabolites were extracted into ethyl acetate/toluene (1:1 vol/vol, water-saturated), an aliquot of which was subjected to scintillation spectrometry to determine radioactive content. MAO-A substrate kinetics was determined using protein (100 μg per reaction) from HT-22 cells pre-incubated in the absence or presence of Ca2+ (1 mM; 20 min, room temperature) and subsequently incubated with increasing concentrations of [14C]-5-HT [15 μM-4 mM]. Incubation in oxygenated potassium phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 7.8) and extraction of labeled metabolites proceeded as described above. Data were analyzed for estimates of Km and Vmax using the Prism v3.01 software.

Transient overexpression of CB-28K

The pREP-CB-28K (calbindin-D28K) plasmid expression vector was kindly provided by Dr. A. Pollock (University of California, San Francisco, CA). HT-22 cells were seeded in log phase and transfected with plasmid DNA (1–2 μg/well on a 24-well plate; seeded at 5 × 105 cells/well) using ExGen™500 (Fermentas) according to the manufacturer's directions. Expression of eGFP fluorescent protein revealed a transfection efficiency of approximately 50% using this technique. Cells were routinely harvested 24 h post-transfection.

Immunodetection of target proteins

Treated HT-22 cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and proteins were extracted in ice-cold lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5), containing protease inhibitor cocktail and 1 mM orthovanadate. Standard denaturing (SDS-PAGE) conditions were used to resolve proteins, which were then transferred to nitrocellulose. Protein expression in total cell lysates (20–30 μg/lane, precleared; 5000 × g, 10 min, 4°C) was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence. Depicted immunoblots are representative of two-three independent experiments.

Determination of target mRNA by semi-quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR)

Total RNA from treated HT-22 cells was prepared with TRIZOL reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol and digested with RNase-free DNase to clear residual genomic DNA. First strand cDNA was reverse-transcribed from 2 μg of total RNA using oligo-(dT) (SuperScript™III First-Strand Synthesis System, Invitrogen). The cDNA was amplified using Taq polymerase and primer pairs (mao-A: forward: 5'-GAA GCT GAG CTC TCC TGT TAC-3'; reverse: 5'-ACA AAG CAG AGA AGA GCC AC-3'; mao-B: forward: 5'-GCT GAA GAG TGG GAC TAC ATG AC-3'; reverse: 5'-GGA ATG AAC CTT GGG AGG TG-3'; β-actin: forward: 5'-TAG AAG CAT TTG CGG TGC ACG-3'; reverse: 5'-TGC CCA TCT ATG AGG GTT ACG-3'). The resultant semi-quantitative PCR products were electrophoresed on agarose gel and visualized using ethidium bromide staining.

Fluorescence determination of free intracellular Ca2+

HT-22 cells were loaded with the fluorescent dye Fluo3-acetoxymethyl ester (Fluo-3-AM; Molecular Probes) at 4 μM for 30 min at 37°C [36]. Fluorescence was visualized at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 550 nm on an Olympus FV300 Confocal Laser Scanning Biological Microscope.

Visualization of cytoplasmic peroxide radicals

2',7'-Dihydrodichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH2-DA) [37] permeates the cell membrane and is hydrolyzed to DCFH2, a nonfluorescent compound that remains trapped within the cell, but which yields a fluorescent product upon oxidation by H2O2. The cells were seeded on cover-slips. After treatment, the cells were rinsed twice with PBS and incubated with DCFH2-DA (5 μM, 30 min at 37°C) or DMSO, vehicle). The cells were washed in prewarmed HEPES-buffered (20 mM) HBSS (pH 7.0) containing 5 mM glucose, and prepared for DCF fluorescence (excitation: 488 nm; emission: 530 ± 15 nm).

Rat primary hippocampal culture

Animal care followed protocols and guidelines approved by University of Saskatchewan Animal Care Committee and the Canadian Council on Animal Care. Rat hippocampal cultures were prepared from E18 fetuses (time-pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats; Charles River Canada, Montreal, PQ, Canada) as described before with some modifications [38]. In brief, the hippocampus was dissected in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS) supplemented with 15 mM HEPES and penicillin (100 U/ml)-streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (Gibco). Collected tissues were digested at 37°C with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA 15 min. The reaction was quenched with fetal bovine serum (FBS, 10%) and tissues were rinsed 3–4 times with HBSS to remove FBS. Following centrifugation at 800 × g for 10 min, the medium was removed and cells were resuspended in a chemically defined serum-free NeuroBasal medium supplemented with 1% N2, 2% B27, 50 μM L-glutamine, 15 mM HEPES, 10 U/ml penicillin and 10 μg/ml streptomycin. Neurons were then plated on coverslips (coated with 25 μg/ml poly-D-lysine), and grown at 37°C with 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere. The medium was replaced 24 h later with fresh NeuroBasal medium lacking L-glutamine and antibiotics. Medium was replaced after 4–5 days in vitro (DIV). Neurons were treated on DIV 7, following which they were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.01 M PBS for 20 min at room temperature, washed several times with PBS, and stained with Hoechst 33258 (500 ng/ml, 10 min) for microscopic visualization of chromatin condensation (a characteristic of apoptotic cell death).

Statistical analyses

Significance (set at P < 0.05) was assessed by unpaired t-tests or by one-way ANOVA with post hoc analyses relying on Bonferonni's Multiple Comparison Test (GraphPad Prism v3.01). Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Results

Low millimolar concentrations of Ca2+increase MAOA activity in HT-22 cells

MAO-A activity in HT-22 cell extracts incubated with Ca2+ (range: 0.1–10 mM) was increased, with a peak (~20% above baseline) around 0.5–1 mM Ca2+ (Fig. 1A). Ca2+ did not exert any effect on MAO-B activity (Fig. 1B). Mg2+ on its own did not exert any effect on MAO-A activity, but it did inhibit the effect of Ca2+ (Fig. 1C).

Effect of Ca2+ on MAO activity in the mouse hippocampal HT-22 cell line. HT-22 cell lysates (100 μg/100 μL; n = 4) were incubated with increasing concentrations of Ca2+ and assayed radioenzymatically for (A) MAO-A and (B) MAO-B activities. (C) HT-22 lysates (n = 3) were incubated with either Ca2+ or the Ca2+ antagonist Mg2+ (1 mM) or co-incubated with Ca2+ (1 mM) and increasing concentrations of Mg2+ to test for the potential of Mg2+ to block Ca2+ (1 mM)-sensitive MAO-A activity. **: P < 0.01, ***: P < 0.001 vs. control. Data represent mean ± SD.

Examination of the kinetics of MAO-A activity in the presence of Ca2+ revealed a decrease in Km (μM) [97.6 ± 6.99 with Ca2+ vs. 125.8 ± 21.02 without Ca2+; n = 3, P = 0.0462, t = 2.203, df = 4], indicating that Ca2+ facilitates the enzymatic reaction. Vmax (nmol/h/mg protein) remained unchanged [74.4 ± 2.9 with Ca2+, vs. 72.4 ± 1.2 without Ca2+; n = 3, P = 0.1672, t = 1.051, df = 4], suggesting that Ca2+ was acting via an allosteric mechanism (Fig. 2A,B). This was more evident on a double-reciprocal plot of the data: the slope (e.g. Km/Vmax) was changed [0.0441 ± 0.0009 (without Ca2+: r2 = 0.9973) vs. 0.0328 ± 0.0007 (with Ca2+: r2 = 0.9967)], whereas the y-intercept (e.g. 1/Vmax) was not [3.13 ± 0.21e-4 (without Ca2+) vs. 3.20 ± 0.18e-4 (with Ca2+)] (Fig. 2C).

Effect of Ca2+ on MAO-A substrate kinetics in HT-22 hippocampal cell line. (A) HT-22 cell lysates (100 μg/100 μL; n = 3) were incubated with increasing concentrations of substrate, e.g. [14C]-5-HT in the absence (○) or presence (●) of Ca2+ (1 mM). The individual curves represent data pooled from three independent experiments. Data are presented as mean ± SD. (B) The highlighted part of the curves in (A) is expanded to demonstrate the change in Km. (C) Data presented on a double-reciprocal plot clearly demonstrate a change in slope (e.g. Km/Vmax) with no change in y-intercept (e.g. 1/Vmax).

The Ca2+ionophore A23187 increases MAO-A activity

HT-22 cells were treated with the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 (5 μM; 30 min) so as to examine the effect of increasing Ca2+ availability on MAO-A activity in living cells. Fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3A) confirmed a significant increase in free Ca2+ as well as a selective 43% increase in MAO-A activity (control: 55.3 ± 9.4 nmol/h/mg protein versus A23187: 79.1 ± 15.5 nmol/h/mg protein; n = 3, P = 0.0424, t = 2.270, df = 4) (Fig. 3B). MAO-A protein expression was unchanged compared to control levels (Fig. 3C). The expression of mao-A gene (expressed as a ratio to GAPDH) was also not affected by A23187 treatment [control: 100.0% ± 11.2; A23187: 102.0% ± 2.1; n = 3, P = 0.7760, t = 0.3044, df = 4] (Fig. 3D, E). Neither MAO-B activity [control: 18.92 ± 2.11 nmol/h/mg protein versus A23187: 18.33 ± 1.74 nmol/h/mg protein; n = 3, P = 0.5914, t = 0.5826, df = 4] nor gene expression [control: 100.0% ± 4.5; with A23187: 92.0% ± 8.2; n = 3, P = 0.2127, t = 1.481, df = 4] was affected by A23187. An increase in cytoplasmic reactive oxygen species (ROS) was observed, which was partly blocked by pretreatment with the MAO-A inhibitor clorgyline (100 μM; 1 hour) (Fig. 3F).

The Ca2+ ionophore A23187 increases MAO-A activity. (A) Levels of free intracellular Ca2+, [Ca2+]i, in HT-22 cells treated with A23187 (5 μM: 30 min) were determined using the Ca2+-binding Fluo-3 AM fluorescent dye. (B) MAO-A and MAO-B activities were assessed radioenzymatically in A23187-treated cell cultures (*P < 0.05 versus control levels). (C) MAO-A protein expression was determined in SDS-PAGE resolved total cell lysates. Levels of β-actin demonstrate equal protein loading. (D) Densitometry graph representing mao-A gene expression (as a ratio to GAPDH expression) determined using semi-quantitative RT-PCR amplification of mRNA extracted from A23187-treated cell cultures. (E) Representative RT-PCR amplification fragments. (F) In similarly-treated cells, the production of ROS was assessed using the H2O2-binding DCF fluorogen. A parallel series of cell cultures were pre-treated with the specific MAO-A inhibitor, clorgyline (CLG; 100 μM, 1 h). Data represent mean ± SD.

Reduction of free intracellular Ca2+by overexpression of CB-28K reduces MAO-A activity

HT-22 cells were transfected with either the vector control (pREP) or the pREP-CB-28K expression plasmid (Fig. 4). Overexpression of CB-28K (24 h) reduced the level of intracellular free Ca2+ and decreased constitutive ROS levels (Fig. 4A). Overexpressed CB-28K induced a decrease (36%) in basal MAO-A activity [pREP: 69.4 ± 16.4 nmol/h/mg protein versus pREP-CB-28K: 44.4 ± 10.2 nmol/h/mg protein; n = 4, P = 0.0440, t = 2.246, df = 6] (Fig. 4B). CB-28K overexpression was confirmed by western blot (Fig. 4C) and it did not affect the expression of either mao-A gene (expressed as a ratio to β-actin) [with pREP: 100.0% ± 9.8; with pREP-CB-28K: 113.0% ± 9.9; n = 3, P = 0.1116, t = 1.864, df = 4] or protein (Fig. 4D, E). Neither MAO-B activity [pREP: 8.4 ± 0.47 nmol/h/mg protein versus pREP-CB-28K: 7.0 ± 3.22 nmol/h/mg protein; n = 4, P = 0.4226, t = 0.8604, df = 6] nor gene expression [with pREP: 100.0% ± 16.1; with pREP-CB-28K: 104.0% ± 17.3; n = 3, P = 0.7841, t = 0.2930, df = 4] was affected by CB-28K overexpression.

Overexpression of the Ca2+-binding protein CB-28K decreases MAO-A activity. HT-22 cells were transfected with the pREP plasmid (Vector) or the pREP-CB-28K expression vector (CB-28K). (A) The effect of CB-28K overexpression (24 h) on free intracellular Ca2+, [Ca2+]i, and on ROS production was examined. (note, the relative fluorescence intensity used for this set of ROS experiments was increased intentionally so as to avoid a "floor" effect, i.e. so that a decrease in ROS production could be demonstrated in CB-28K-overexpressing cells). (B) MAO-A and MAO-B activities were assessed radioenzymatically in corresponding cell lysates (*P < 0.05 versus control levels). (C) SDS-PAGE-resolved total cellular proteins were probed for CB-28K overexpression and for the expression of MAO-A and β-actin (used as a loading control). (D) Densitometry graph representing mao-A gene expression (relative to β-actin expression) determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR, represented in (E). Data are presented as mean ± SD.

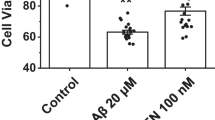

Immortalized and primary hippocampal toxicity associated with the Alzheimer disease-related peptide, Aβ, relies partly on a MAO-A sensitive mechanism

HT-22 cells treated with the AD-related Aβ(1–40) peptide (30 μM; 48 h) had significantly more free Ca2+ (Fig. 5A, top panels) and a corresponding increase in ROS production (Fig. 5A, middle panels) that was decreased by pretreatment with the MAO-A inhibitor clorgyline (100 μM, 1 h) (Fig. 5A, bottom panels). Hoechst staining, which labels all cell nuclei including those that have chromatin condensation (a sign of apoptotic processing), revealed a significant increase in apoptotic primary hippocampal neurons in cultures treated with Aβ(1–42) (10 μM, 24 h) (Fig. 5B) [F(4,11) = 69.16, P < 0.0001]. Post-hoc analysis revealed that the effect of Aβ(1–42) [P < 0.001] was greatly attenuated by pre-treatment with the MAO-A inhibitor clorgyline (100 μM; 1 h) [P < 0.01] (Fig. 5C).

ROS production induced by the Alzheimer disease-related peptide, Aβ, is diminished by MAO-A inhibition. HT-22 cells were treated with Aβ(1–40) (30 μM, 48 h). The effect of Aβ(1–40) on (A) free intracellular Ca2+, assessed using FLUO-3AM fluorescence, and on the production of ROS, assessed using the H2O2-binding DCF fluorogen. (B) Hoechst staining of primary hippocampal cell cultures was used to determine the proportion of cells exhibiting chromatin condensation (an indication of apoptotic cell death: arrows) in Aβ(1–42)-treated cultures. In both HT-22 cultures (A) and primary neuronal cultures (B), the effect of Aβ was reversed by pretreatment with the specific MAO-A inhibitor, clorgyline (CLG; 100 μM, 1 h). (C) Number of primary hippocampal cells (expressed as a percentage of control) that exhibit chromatin condensation following treatment with Aβ and/or CLG (groups shown in B). ***: P < 0.001 vs. control. ##: P < 0.01 between the indicated groups. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Discussion

H2O2 is a natural by-product of MAO-A-mediated degradation of amines [38]. The normal aging process and various neurodegenerative processes such as Parkinson's disease [39] and Alzheimer's disease [40, 41] could well be affected by oxidative stress associated with enhanced MAO-generated levels of H2O2.

We demonstrate that the selective response of MAO-A to Ca2+ (and its sensitivity to Mg2+, a physiologic Ca2+ antagonist [42]) occurs in immortalized HT-22 hippocampal cells and confirms observations using brain extracts from monkey [29], mouse [30], rat [31] and human (DDM: unpublished data). The effect of Ca2+ on MAO-A activity in our cultures appears modest; however, Meyer et al [13] have recently demonstrated that untreated depressed patients have levels of MAO-A density that are only 34% higher than that found in controls. Yet these same authors propose that this modest change could account for most of the change in biogenic amine levels observed in these patients. Obviously, small changes in MAO-A can significantly impact brain function.

While low millimolar levels of Ca2+ are necessary to reveal this effect, the fact that MAO-B activity remains unaffected clearly supports differences in MAO-A and MAO-B regulation. The need for millimolar concentrations also suggests pathological relevance. Interestingly, the mitochondria can modulate cytoplasmic Ca2+ homeostasis by accumulating Ca2+ into the very high micromolar range [43]. Furthermore, elevated Ca2+ concentrations localized to microdomains may also represent unique means of modulating localized mitochondrial membrane and/or matrix function [44], including the activation of dehydrogenases [45]. In neurons and chromaffin cells, mitochondria rapidly and reversibly buffer Ca2+ during cell stimulation to help clear large Ca2+ loads [46–48]. The ensuing overloading of mitochondria with Ca2+ may be involved in several pathological conditions, including ischemia-reperfusion lesions, neurotoxicity and neurodegenerative diseases, where ATP depletion, overproduction of ROS and release of apoptotic factors lead to cell damage [49].

Using the Ca2+ ionophore A23187, we now confirm that increasing free intracellular Ca2+ well above normal levels selectively increases MAO-A activity in living hippocampal HT-22 cells. The associated increase in peroxyradicals is moderately decreased by MAO-A inhibition, supporting a contribution by the enzyme to A23187-associated toxicity. Intracellular Ca2+ levels can also be quenched by specific proteins including calbindin-28K (CB-28K), the predominant Ca2+-binding protein in brain [50]. Overexpression of CB-28K in HT-22 cells significantly decreased free Ca2+ levels and significantly decreased MAO-A activity. Again MAO-B activity was spared. The effects of both A23187 and CB-28K occurred independent of any change in the expression level of MAO-A protein (or mao-A gene), which, in combination with our demonstration of affinity changes of the MAO-A enzyme in the presence of Ca2+, suggests a functional modification of the MAO-A protein itself. These combined data implicate a CB-28K-dependent, Ca2+-sensitive component to MAO-A function, which could be exacerbated when CB-28K expression levels are compromised, such as in normal aging or, more importantly, during neurodegenerative processes [16, 34, 51]. In support of this, an age-related loss of CB-28K immunoreactive basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in cortical regions and in the dentate gyrus (hippocampus) has been shown in several species including dog, mouse and rat [34] and references therein). Furthermore, in AD-related pathology, a substantially greater loss of CB-28K immunoreactivity is observed, with the diminished capacity of the cell to buffer intracellular Ca2+ being considered as a core factor in the pathogenesis of AD [51–54]. This is corroborated by the ability of ectopic CB-28K to protect cell cultures against apoptosis, including that induced by the AD-related peptide β-amyloid [55–58] and by the fact that alterations in Ca2+ signalling can occur early in AD, well before any obvious extracellular Aβ deposition [59]. Furthermore, dihydropyridine Ca2+ channel blockers, which are known to block the selective increase in MAO-A in the senescence-accelerated mouse model [32], may improve learning and performance in animals [60] and may improve age-associated and AD-related memory impairment in humans [61, 62]. As CB-28K and MAO-A immunoreactivities are often co-localized and cells immunoreactive for both proteins are reduced during AD [54, 63], it is not unreasonable to suppose that a loss of CB-28K could facilitate MAO-A-mediated H2O2 production in an increasingly toxic Aβ environment, leading to localized cell death. Treatment with Aβ(1–40) increases intracellular levels of Ca2+ [64] [present study], possibly through its effect on the ryanodine receptor [65]. A pathological contribution by MAO-A in AD is further suggested by the accumulation of toxic metabolites of MAO-mediated deamination in AD patients [66] as well as by the ability of MAO-A inhibition to reduce the ROS production associated with treatment of HT-22 cells with the AD-related Aβ(1–40) peptide (present study). Primary hippocampal neuronal cultures are also particularly sensitive to Aβ peptide [67] and Aβ-induced toxicity in these cells is also sensitive to MAO-A inhibition (present study). Experimentation based on in vivo assessment of the effect of Ca2+ on MAO-A as well as a closer examination of the relation between Ca2+/CB-28K and MAO-A in AD tissues is warranted.

MAO-A is a risk factor in AD and changes in MAO-A activity parallel changes in the production of ROS, e.g. H2O2. Given the neuroprotective role of CB-28K in human pathologies such as AD (and in models of AD), in addition to our demonstration that the toxicity of the AD-related peptide, Aβ, is sensitive to MAO-A inhibition, we suggest that part of the oxidative stress associated with AD may rely on a Ca2+/CB-28K-sensitive, MAO-A-mediated mechanism.

Conclusion

The availability of free intracellular Ca2+ is positively correlated with the activity of MAO-A, a mitochondrial H2O2-generating enzyme. The influence of Ca2+ on MAO-A function could potentially impact AD-related pathology, which is often associated with altered Ca2+ homeostasis, mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress.

References

Sies H: Strategies of antioxidant defense. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS. 1993, 215 (2): 213-219. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18025.x.

Zhu Y, Carvey PM, Ling Z: Age-related changes in glutathione and glutathione-related enzymes in rat brain. Brain research. 2006, 1090 (1): 35-44. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.063.

Crack PJ, Cimdins K, Ali U, Hertzog PJ, Iannello RC: Lack of glutathione peroxidase-1 exacerbates Abeta-mediated neurotoxicity in cortical neurons. J Neural Transm. 2006, 113 (5): 645-657. 10.1007/s00702-005-0352-y.

Youdim MB, Edmondson D, Tipton KF: The therapeutic potential of monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Nature reviews. 2006, 7 (4): 295-309. 10.1038/nrn1883.

Magyar K, Palfi M, Tabi T, Kalasz H, Szende B, Szoko E: Pharmacological aspects of (-)-deprenyl. Current medicinal chemistry. 2004, 11 (15): 2017-2031.

Magyar K, Szende B: (-)-Deprenyl, a selective MAO-B inhibitor, with apoptotic and anti-apoptotic properties. Neurotoxicology. 2004, 25 (1-2): 233-242. 10.1016/S0161-813X(03)00102-5.

Riederer P, Lachenmayer L, Laux G: Clinical applications of MAO-inhibitors. Current medicinal chemistry. 2004, 11 (15): 2033-2043.

Saura J, Luque JM, Cesura AM, Da Prada M, Chan-Palay V, Huber G, Loffler J, Richards JG: Increased monoamine oxidase B activity in plaque-associated astrocytes of Alzheimer brains revealed by quantitative enzyme radioautography. Neuroscience. 1994, 62 (1): 15-30. 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90311-5.

McLellan ME, Kajdasz ST, Hyman BT, Bacskai BJ: In vivo imaging of reactive oxygen species specifically associated with thioflavine S-positive amyloid plaques by multiphoton microscopy. J Neurosci. 2003, 23 (6): 2212-2217.

Shih JC, Chen K, Ridd MJ: Monoamine oxidase: from genes to behavior. Annual review of neuroscience. 1999, 22: 197-217. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.197.

Brunner HG, Nelen M, Breakefield XO, Ropers HH, van Oost BA: Abnormal behavior associated with a point mutation in the structural gene for monoamine oxidase A. Science (New York, NY. 1993, 262 (5133): 578-580.

Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt TE, Mill J, Martin J, Craig IW, Taylor A, Poulton R: Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science (New York, NY. 2002, 297 (5582): 851-854.

Meyer JH, Ginovart N, Boovariwala A, Sagrati S, Hussey D, Garcia A, Young T, Praschak-Rieder N, Wilson AA, Houle S: Elevated monoamine oxidase a levels in the brain: an explanation for the monoamine imbalance of major depression. Archives of general psychiatry. 2006, 63 (11): 1209-1216. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1209.

Thorpe L, Groulx B: Depressive syndromes in dementia. The Canadian journal of neurological sciences. 2001, 28 Suppl 1: S83-95.

Nishimura AL, Guindalini C, Oliveira JR, Nitrini R, Bahia VS, de Brito-Marques PR, Otto PA, Zatz M: Monoamine oxidase a polymorphism in Brazilian patients: risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer's disease?. J Mol Neurosci. 2005, 27 (2): 213-217. 10.1385/JMN:27:2:213.

Wu CK, Mesulam MM, Geula C: Age-related loss of calbindin from human basal forebrain cholinergic neurons. Neuroreport. 1997, 8 (9-10): 2209-2213.

Emilsson L, Saetre P, Balciuniene J, Castensson A, Cairns N, Jazin EE: Increased monoamine oxidase messenger RNA expression levels in frontal cortex of Alzheimer's disease patients. Neuroscience letters. 2002, 326 (1): 56-60. 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00307-5.

Takehashi M, Tanaka S, Masliah E, Ueda K: Association of monoamine oxidase A gene polymorphism with Alzheimer's disease and Lewy body variant. Neuroscience letters. 2002, 327 (2): 79-82. 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00258-6.

Amrein R, Martin JR, Cameron AM: Moclobemide in patients with dementia and depression. Advances in neurology. 1999, 80: 509-519.

Gareri P, Falconi U, De Fazio P, De Sarro G: Conventional and new antidepressant drugs in the elderly. Progress in neurobiology. 2000, 61 (4): 353-396. 10.1016/S0301-0082(99)00050-7.

Rosenzweig P, Patat A, Zieleniuk I, Cimarosti I, Allain H, Gandon JM: Cognitive performance in elderly subjects after a single dose of befloxatone, a new reversible selective monoamine oxidase A inhibitor. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 1998, 64 (2): 211-222.

Malorni W, Giammarioli AM, Matarrese P, Pietrangeli P, Agostinelli E, Ciaccio A, Grassilli E, Mondovi B: Protection against apoptosis by monoamine oxidase A inhibitors. FEBS letters. 1998, 426 (1): 155-159. 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00315-9.

Maher P, Davis JB: The role of monoamine metabolism in oxidative glutamate toxicity. J Neurosci. 1996, 16 (20): 6394-6401.

Maragos WF, Young KL, Altman CS, Pocernich CB, Drake J, Butterfield DA, Seif I, Holschneider DP, Chen K, Shih JC: Striatal damage and oxidative stress induced by the mitochondrial toxin malonate are reduced in clorgyline-treated rats and MAO-A deficient mice. Neurochemical research. 2004, 29 (4): 741-746. 10.1023/B:NERE.0000018845.82808.45.

Ou XM, Chen K, Shih JC: Monoamine oxidase A and repressor R1 are involved in apoptotic signaling pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006, 103 (29): 10923-10928. 10.1073/pnas.0601515103.

Ward MW, Kushnareva Y, Greenwood S, Connolly CN: Cellular and subcellular calcium accumulation during glutamate-induced injury in cerebellar granule neurons. Journal of neurochemistry. 2005, 92 (5): 1081-1090. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02928.x.

Rao VL: Nitric oxide in hepatic encephalopathy and hyperammonemia. Neurochemistry international. 2002, 41 (2-3): 161-170. 10.1016/S0197-0186(02)00038-4.

Mousseau DD, Baker GB, Butterworth RF: Increased density of catalytic sites and expression of brain monoamine oxidase A in humans with hepatic encephalopathy. Journal of neurochemistry. 1997, 68 (3): 1200-1208.

Egashira T, Sakai K, Sakurai M, Takayama F: Calcium disodium edetate enhances type A monoamine oxidase activity in monkey brain. Biological trace element research. 2003, 94 (3): 203-211. 10.1385/BTER:94:3:203.

Samantaray S, Chandra G, Mohanakumar KP: Calcium channel agonist, (+/-)-Bay K8644, causes a transient increase in striatal monoamine oxidase activity in Balb/c mice. Neuroscience letters. 2003, 342 (1-2): 73-76. 10.1016/S0304-3940(03)00238-6.

Kosenko EA, Venediktova NI, Kaminskii Iu G: [Calcium and ammonia stimulate monoamine oxidase A activity in brain mitochondria]. Izvestiia Akademii nauk. 2003, 542-546.

Kabuto H, Yokoi I, Mori A, Murakami M, Sawada S: Neurochemical changes related to ageing in the senescence-accelerated mouse brain and the effect of chronic administration of nimodipine. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 1995, 80 (1): 1-9. 10.1016/0047-6374(94)01542-T.

Zatta P, Nicosia V, Zambenedetti P: Evaluation of MAO activities on murine neuroblastoma cells upon acute or chronic treatment with aluminium (III) or tacrine. Neurochemistry international. 1998, 32 (3): 273-279. 10.1016/S0197-0186(97)00095-8.

Bu J, Sathyendra V, Nagykery N, Geula C: Age-related changes in calbindin-D28k, calretinin, and parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons in the human cerebral cortex. Experimental neurology. 2003, 182 (1): 220-231. 10.1016/S0014-4886(03)00094-3.

Geula C, Nagykery N, Wu CK, Bu J: Loss of calbindin-D28K from aging human cholinergic basal forebrain: relation to plaques and tangles. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2003, 62 (6): 605-616.

Kirischuk S, Pronchuk N, Verkhratsky A: Measurements of intracellular calcium in sensory neurons of adult and old rats. Neuroscience. 1992, 50 (4): 947-951. 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90217-P.

Holt A, Baker GB: Inhibition of rat brain monoamine oxidase enzymes by fluoxetine and norfluoxetine. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's archives of pharmacology. 1996, 354 (1): 17-24. 10.1007/BF00168701.

Shih JC: Molecular basis of human MAO A and B. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1991, 4 (1): 1-7.

Jenner P, Olanow CW: Oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 1996, 47 (6 Suppl 3): S161-70.

Kennedy BP, Ziegler MG, Alford M, Hansen LA, Thal LJ, Masliah E: Early and persistent alterations in prefrontal cortex MAO A and B in Alzheimer's disease. J Neural Transm. 2003, 110 (7): 789-801.

Sherif F, Gottfries CG, Alafuzoff I, Oreland L: Brain gamma-aminobutyrate aminotransferase (GABA-T) and monoamine oxidase (MAO) in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Journal of neural transmission. 1992, 4 (3): 227-240. 10.1007/BF02260906.

Altura BM: Calcium antagonist properties of magnesium: implications for antimigraine actions. Magnesium. 1985, 4 (4): 169-175.

Montero M, Alonso MT, Carnicero E, Cuchillo-Ibanez I, Albillos A, Garcia AG, Garcia-Sancho J, Alvarez J: Chromaffin-cell stimulation triggers fast millimolar mitochondrial Ca2+ transients that modulate secretion. Nature cell biology. 2000, 2 (2): 57-61. 10.1038/35000001.

Rizzuto R, Pozzan T: Microdomains of intracellular Ca2+: molecular determinants and functional consequences. Physiological reviews. 2006, 86 (1): 369-408. 10.1152/physrev.00004.2005.

Robb-Gaspers LD, Burnett P, Rutter GA, Denton RM, Rizzuto R, Thomas AP: Integrating cytosolic calcium signals into mitochondrial metabolic responses. The EMBO journal. 1998, 17 (17): 4987-5000. 10.1093/emboj/17.17.4987.

White RJ, Reynolds IJ: Mitochondria accumulate Ca2+ following intense glutamate stimulation of cultured rat forebrain neurones. The Journal of physiology. 1997, 498 ( Pt 1): 31-47.

Herrington J, Park YB, Babcock DF, Hille B: Dominant role of mitochondria in clearance of large Ca2+ loads from rat adrenal chromaffin cells. Neuron. 1996, 16 (1): 219-228. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80038-0.

Xu T, Naraghi M, Kang H, Neher E: Kinetic studies of Ca2+ binding and Ca2+ clearance in the cytosol of adrenal chromaffin cells. Biophysical journal. 1997, 73 (1): 532-545.

Duchen MR: Contributions of mitochondria to animal physiology: from homeostatic sensor to calcium signalling and cell death. The Journal of physiology. 1999, 516 ( Pt 1): 1-17. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.001aa.x.

Baimbridge KG, Celio MR, Rogers JH: Calcium-binding proteins in the nervous system. Trends in neurosciences. 1992, 15 (8): 303-308. 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90081-I.

Wu CK, Nagykery N, Hersh LB, Scinto LF, Geula C: Selective age-related loss of calbindin-D28k from basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus). Neuroscience. 2003, 120 (1): 249-259. 10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00248-3.

Palop JJ, Jones B, Kekonius L, Chin J, Yu GQ, Raber J, Masliah E, Mucke L: Neuronal depletion of calcium-dependent proteins in the dentate gyrus is tightly linked to Alzheimer's disease-related cognitive deficits. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003, 100 (16): 9572-9577. 10.1073/pnas.1133381100.

Thibault O, Porter NM, Chen KC, Blalock EM, Kaminker PG, Clodfelter GV, Brewer LD, Landfield PW: Calcium dysregulation in neuronal aging and Alzheimer's disease: history and new directions. Cell calcium. 1998, 24 (5-6): 417-433. 10.1016/S0143-4160(98)90064-1.

Chan-Palay V, Hochli M, Savaskan E, Hungerecker G: Calbindin D-28k and monoamine oxidase A immunoreactive neurons in the nucleus basalis of Meynert in senile dementia of the Alzheimer type and Parkinson's disease. Dementia (Basel, Switzerland). 1993, 4 (1): 1-15. 10.1159/000107290.

Yenari MA, Minami M, Sun GH, Meier TJ, Kunis DM, McLaughlin JR, Ho DY, Sapolsky RM, Steinberg GK: Calbindin d28k overexpression protects striatal neurons from transient focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2001, 32 (4): 1028-1035.

Phillips RG, Meier TJ, Giuli LC, McLaughlin JR, Ho DY, Sapolsky RM: Calbindin D28K gene transfer via herpes simplex virus amplicon vector decreases hippocampal damage in vivo following neurotoxic insults. Journal of neurochemistry. 1999, 73 (3): 1200-1205. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731200.x.

Wernyj RP, Mattson MP, Christakos S: Expression of calbindin-D28k in C6 glial cells stabilizes intracellular calcium levels and protects against apoptosis induced by calcium ionophore and amyloid beta-peptide. Brain research. 1999, 64 (1): 69-79. 10.1016/S0169-328X(98)00307-6.

Mattson MP, Rychlik B, Chu C, Christakos S: Evidence for calcium-reducing and excito-protective roles for the calcium-binding protein calbindin-D28k in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1991, 6 (1): 41-51. 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90120-O.

Brorson JR, Bindokas VP, Iwama T, Marcuccilli CJ, Chisholm JC, Miller RJ: The Ca2+ influx induced by beta-amyloid peptide 25-35 in cultured hippocampal neurons results from network excitation. Journal of neurobiology. 1995, 26 (3): 325-338. 10.1002/neu.480260305.

Quevedo J, Vianna M, Daroit D, Born AG, Kuyven CR, Roesler R, Quillfeldt JA: L-type voltage-dependent calcium channel blocker nifedipine enhances memory retention when infused into the hippocampus. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 1998, 69 (3): 320-325. 10.1006/nlme.1998.3822.

Heidrich A, Rosler M, Riederer P: [Pharmacotherapy of Alzheimer dementia: therapy of cognitive symptoms--new results of clinical studies]. Fortschritte der Neurologie-Psychiatrie. 1997, 65 (3): 108-121.

Yamada M, Itoh Y, Suematsu N, Otomo E, Matsushita M: Apolipoprotein E genotype in elderly nondemented subjects without senile changes in the brain. Annals of neurology. 1996, 40 (2): 243-245. 10.1002/ana.410400217.

Yew DT, Chan WY: Early appearance of acetylcholinergic, serotoninergic, and peptidergic neurons and fibers in the developing human central nervous system. Microscopy research and technique. 1999, 45 (6): 389-400. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19990615)45:6<389::AID-JEMT6>3.0.CO;2-Z.

Smith IF, Green KN, LaFerla FM: Calcium dysregulation in Alzheimer's disease: recent advances gained from genetically modified animals. Cell calcium. 2005, 38 (3-4): 427-437. 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.06.021.

Supnet C, Grant J, Kong H, Westaway D, Mayne M: Amyloid-beta-(1-42) increases ryanodine receptor-3 expression and function in neurons of TgCRND8 mice. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006, 281 (50): 38440-38447. 10.1074/jbc.M606736200.

Burke WJ, Li SW, Chung HD, Ruggiero DA, Kristal BS, Johnson EM, Lampe P, Kumar VB, Franko M, Williams EA, Zahm DS: Neurotoxicity of MAO metabolites of catecholamine neurotransmitters: role in neurodegenerative diseases. Neurotoxicology. 2004, 25 (1-2): 101-115. 10.1016/S0161-813X(03)00090-1.

Liu Y, Piasecki D: A cell-based method for the detection of nanomolar concentrations of bioactive amyloid. Analytical biochemistry. 2001, 289 (2): 130-136. 10.1006/abio.2000.4928.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded, in part, by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and by the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation (DDM) and, in part, by the Aruna and Kripa Thakur award (XC), Department of Psychiatry, University of Saskatchewan. ZW is a recipient of a CIHR/Rx&D Research Program & AstraZeneca/Alzheimer Society of Canada Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declares that there are no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

XC carried out the majority of the work. ZW purified and cultured the primary hippocampal cells. GGG participated in the FLUO-3AM microscopy studies. XC, XL and DDM drafted the manuscript. DDM conceived and designed the study, and coordinated data collection and analysis. All authors read, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, X., Wei, Z., Gabriel, G.G. et al. Calcium-sensitive regulation of monoamine oxidase-A contributes to the production of peroxyradicals in hippocampal cultures: implications for Alzheimer disease-related pathology. BMC Neurosci 8, 73 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-8-73

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-8-73