Abstract

Background

Microorganisms are a large and diverse form of life. Many of them live in association with large multicellular organisms, developing symbiotic relations with the host and some have even evolved to form obligate endosymbiosis [1]. All Carpenter ants (genus Camponotus) studied hitherto harbour primary endosymbiotic bacteria of the Blochmannia genus. The role of these bacteria in ant nutrition has been demonstrated [2] but the omnivorous diet of these ants lead us to hypothesize that the bacteria might provide additional advantages to their host. In this study, we establish links between Blochmannia, growth of starting new colonies and the host immune response.

Results

We manipulated the number of bacterial endosymbionts in incipient laboratory-reared colonies of Camponotus fellah by administrating doses of an antibiotic (Rifampin) mixed in honey-solution. Efficiency of the treatment was estimated by quantitative polymerase chain reaction and Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), using Blochmannia specific primers (qPCR) and two fluorescent probes (one for all Eubacterial and other specific for Blochmannia). Very few or no bacteria could be detected in treated ants. Incipient Rifampin treated colonies had significantly lower numbers of brood and adult workers than control colonies. The immune response of ants from control and treated colonies was estimated by inserting nylon filaments in the gaster and removing it after 24 h. In the control colonies, the encapsulation response was positively correlated to the bacterial amount, while no correlation was observed in treated colonies. Indeed, antibiotic treatment increased the encapsulation response of the workers, probably due to stress conditions.

Conclusion

The increased growth rate observed in non-treated colonies confirms the importance of Blochmannia in this phase of colony development. This would provide an important selective advantage during colony founding, where the colonies are faced with severe inter and intraspecific competition. Furthermore, the bacteria improve the workers encapsulation response. Thus, these ants are likely to be less susceptible to various pathogen attacks, such as the Phoridae fly parasitoids, normally found in the vicinity of Camponotus nests. These advantages might explain the remarkable ecological success of this ant genus, comprising more than 1000 species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

An increasing set of data is shedding light on the role of microorganisms that have co-evolved with their hosts, including humans [3]. They illustrate the high diversity of endosymbiotic forms among living organisms. Moreover the evidence of gene transfer between bacterial cells or viruses and eukaryotic cells supports the theory of symbiotic relationships as a major force driving evolution [4] and as a source of phenotypic complexity [5]. Multiple new symbionts are regularly discovered in the same host, which can compete or cooperate [3, 6]. Normally, they play a role in host nutrition; defence against pathogens remains an underappreciated benefit of such associations, both in invertebrates and vertebrates [7, 8]. Social insects are particularly concerned as they are highly susceptible to infectious diseases, due to their lifestyle, and have evolved several associations with microorganisms [9].

Endosymbionts are very common among insects, especially in those sucking plant sap, feeding on vertebrate blood for their entire life span, and those that eat wood and keratin. As they are all strict specialists in nourishment, it is assumed that endosymbionts play a role in providing complementary elements absent from these restricted diets. Camponotu s genus, carpenter ants, have established an association with intracellular endosymbionts Blochmannia, a taxon of γ-Proteobacteria, found in all Camponotus species studied hitherto [10]. The bacteria live within specialized cells, the bacteriocytes. The function of the endosymbionts is not fully elucidated but their role as dietary complement suppliers has been pointed out after the genome sequence analysis of two Blochmannia species. The bacteria is probably able to supply nitrogen and sulphur compounds to the host [11–13]. Moreover, bacteria elimination using antibiotic treatment is deleterious and chemically defined diets can complement bacteria suppression [2, 14] demonstrating the necessary nutritional role of bacteria. However, the presence of Blochmannia in omnivorous Camponotus species suggests that bacteria may also have other functions beneficial to the ants. Some studies have suggested that Blochmannia may play a more important role during the colony founding phase and growth rather than in adult worker maintenance [15] or may play a role in pheromone production [16].

Microbes that forms chronic infections in a host lineage may evolve to promote host survival or benefits to its host, as this will help to maintain its immediate ecological resource [17]. In this context, secondary endosymbionts can provide hosts with defences against parasites, beyond nutritional advantages [18, 19]. So far, no similar example with primary endosymbionts has been reported. Externally located bacteria are also capable of conferring protection to insect hosts against parasite infections [20].

Here, we tested the hypotheses that Blochmannia provide faster colony development in the initial stages (incipient colonies) as previously stated [15] and/or improve the host immune system of the host. We used the encapsulation rate as an index of the immune response and analysed whether it was correlated or not with the number of bacteria. The use of incipient colonies, obtained from founding queens, is a suitable choice since it allows the study of animals of similar ages and reduces the effects of natural selection operating on colonies throughout their development.

Results

Endosymbiont identification

The 16S rDNA endosymbiont sequence was deposited in the GenBank database under accession number EF422835. According to the Ribosomal Database Project [21], the 16S rDNA sequence of Camponotus fellah endosymbiont correspond to an unclassified γ-Proteobacteria closely related to 16rDNA sequences from Blochmannia endosymbionts bacteria of various Camponotus ant species. This sequence has G+C content of 47% which is near to that of other Blochmannia symbionts.

When compared with the nucleic sequences of other Blochmannia (tools available in NCBI/Blast), maximum identity ranged from 91–93%. However, other Blochmannia species present in GenBank exhibit up to 98% of identity to each other. Phylogenetic comparisons showed the existence of a monophyletic group containing classified and unclassified endosymbionts from Camponotus ant species, closer to other insect endosymbionts and distinct from other outgroup bacteria (data not published).

The use of FISH with primers specific for Eubacteria and Blochmannia endosymbionts showed that bacteriocytes of midgut preparations were full of bacteria. In these preparations it was possible to see the individual bacterium and its rod form. The bacteriocytes were also detected in the oocytes by FISH as well.

Effectiveness of antibiotic treatment

The quantity of Blochmannia in midgut bacteriocytes was estimated after Rifampin treatment using two complementary methods: real-time quantitative PCR and Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH). The two methods showed a reduction of Blochmannia numbers in midgut bacteriocytes after 12-weeks of antibiotic treatment. Within this period, FISH did not detect the presence of Blochmania in the bacteriocytes (Fig. 1). However quantitative real-time PCR indicated that the bacteria were not completely eliminated as a low quantity of 16S rDNA bacteria molecules can be detected in the midgut. Treated and control groups differed significantly in their content of Blochmannia measured as 16S rDNA molecules (Mann-Whitney's U-test = 179.00, Z = -3.48, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The treatment reduced the quantity of bacteria by 75%. Moreover, the individual variation in bacteria amount was more constant in antibiotic treated colonies than in control colonies.

Endosymbiont number estimation in worker midguts, after 3 months of antibiotic treatment. Workers from treated groups present a mean number of bacteria significantly lower than the control group (Mann-Whitney's U-test = 179.00, Z = -3.48, p < 0.001). The bars represent the mean number of 16S rDNA molecules ± semi-quartile range.

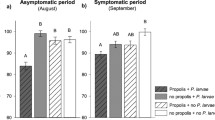

Evaluation of colony development

Each colony was composed of at least one larva, pupa or worker and queen. Colonies composed only with the queen or colonies with a dying queen during the experiment were excluded. After seven months, seven control colonies and nine treated colonies were kept for further analysis. Workers, larvae and pupae numbers were not significantly different during the first three months after the beginning of the experiments. After this time, untreated colonies displayed more accentuated larvae production and had a higher number of adult workers (Fig 3a and 3c, see table 1, for all statistical results). Pupae number varied significantly throughout the time of the experiment but no difference between treated and control colonies was observed (Fig 3b). The variation in workers numbers was significatively different between treated and control colonies with untreated colonies having more workers (Fig 3c).

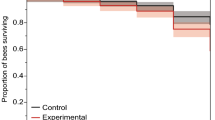

Amount of Blochmannia endosymbiont versus encapsulation response

When expressing encapsulation rate versus 16S rDNA molecules amount (as measure of Blochmannia amount in individual midgut), control and treated colonies displayed different patterns of immune response. We found a significant positive correlation between encapsulation rate and bacteria amount in the ants from control colonies: the bacteria did facilitate the encapsulation response (Pearson's r, p = 0.003, n = 27, Fig. 4). On the contrary, ants from treated colonies did not display a correlation between the amount of bacteria in the midgut and the encapsulation response (Pearson's r, p = 0.92, n = 29, Fig. 4). Thus, it seems that antibiotic treatment eliminated the bacterial effects on the immune encapsulation response. An ANCOVA analysis with the encapsulation rate as independent variable showed that treated workers present a significant increase in encapsulation rate (F1,53 = 8.61, p = 0.005). The regression inclinations of treated and control groups differed significantly (F1,52 = 10.06, p = 0.003).

Discussion and Conclusion

In this study, we confirmed that Blochmannia plays an important role for Camponotus ants by improving the colony growth. We also demonstrated for the first time that Blochmannia interacts with the ant immune defence.

Antibiotic treatment with Rifampin considerably reduced the endosymbiont number in the midgut, although they were never totally eliminated and there was a great variability between workers. This may be due to different access to the antibiotic and some ants may not drink the antibiotic solution or, as observed by Feldhaar et al. (2007), may be explained by the fact that DNA of the endosymbiont may still be detectable by qRT-PCR when bacteria are not alive or active. Additionally, it was confirmed that bacterial sequences were not integrated in the genome of the ant by a PCR test performed on ant DNA from legs using Blochmannia 16S rDNA and ant 18S rDNA primers (data not shown).

The treatment had a remarkable impact on colony development by reducing larvae production and worker numbers, corroborating previous worker [2]. Carrying out the studies in entire incipient colonies, we can demonstrate the importance of endosymbionts in this phase of colony development. According Feldhaar et al. (2007), essential amino acids provided by endosymbionts improve workers ability to raise pupae. Here, we have verified that control colonies exhibited a bigger population in the first seven months of colony development. Since the establishment phase is critical for new colonies, harbouring more bacteria may have major ecological consequences in a context of inter and intraspecific competition: more workers confers a special advantage to maintain a young colony, occupy and monopolize food resources. Indeed, animal protein food resources are more unpredictable in the time-space scale. Blochmannia presence could signify a possible adaptation for ants to fluctuations in protein availability, permitting the colony growth even in absence of preys. We do not know the mechanisms allowing an increase in brood production, beyond the direct nutritional effects on treated queen, but several mechanisms are plausible, including a direct oogenesis control. For example, it has been demonstrated that Wolbachia bacteria are necessary for the host oogenesis in a particular strain of the parasitic wasp Asobara tabida [22]. Furthermore, it was evidenced that apoptosis prevention of nurse cells by Wolbachia can regulate the host oogenesis [23].

We have demonstrated that Blochmannia play another important function by improving Camponotus host immune system. The encapsulation rate measured in Rifampin treated workers was significantly higher when compared with control colonies. Although no evident toxic effect (like increase in mortality) was observed, it is expected that antibiotic treatment has stressing effects on workers and that the increase of the encapsulation rate might correspond to an adaptive response to stress. Furthermore, antibiotic treatment seemed to mask the effects of endosymbiont number on encapsulation response observed in control colonies, where the bacteria favoured the encapsulation response. Positive effects of symbionts on host immune system have been described in the last years. For example, the facultative symbionts of Acyrthosiphon pisum (the pea aphid) confer it resistance to parasitoid attacks [18]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that Wolbachia confer vigorous antiviral protection to Drosophila [19]. The mechanisms by which the resistance is expressed is still unknown, but in another example it was showed that symbiotic bacteria could compete directly for space and resources and thus prevent host colonization by pathogens [24, 25].

Encapsulation is the principal physiological response against parasitoids suggesting an important role of the stimulation induced by Blochmannia in the protection against parasites. This strong interaction between symbiotic bacteria and ants may explain the persistence and broad occurrence of symbiotic bacteria in the Camponotu s genus. Ants from Camponotus genus are abundant almost everywhere in the world where ants are found, comprising more than 600 described species within an estimated number greater than 1,000 species [26]. Its large distribution, the diversity of forms and food behaviour and the occurrence on diverse environments make the system Camponotus/Blochmannia an interesting model to study how ecological forces determine symbiont characteristics and how bacteria determine the ant traits. For example, it is interesting to determine how genetic differences found among different species of Blochmannia could be related to host ecological characteristics.

The social habits of the ants make them particularly vulnerable to several parasites and parasitoids. Phoridae flies are frequently found around Camponotus nests and their influence is fundamental in regulating the ant communities [27]. So, it can be expected that Camponotus species more exposed to Phoridae attack should harbour more bacteria. The physiological mechanism linking bacterial amount and encapsulation response remains unknown. Although the better workers "quality" due to extra nutrients furnished by bacteria is the more probable explanation, direct production of biomolecules in stress situation should not be excluded.

An efficient immune system is a major trait allowing the existence of social insect colonies with thousand of individuals, genetically related [28], living close together, constantly exposed to parasitic disease risks. Competition in the first stages of colony growth constitutes also a great challenge to reach the reproductive stage. Thus, Blochmannia endosymbionts appear to be a fundamental partner, responsible for the ecological success of Camponotus ants. As more than 10% of insect species depend on obligate bacterial mutualists for their viability and reproduction [29], the research on symbiosis between bacteria and animals appears to be a new and promising field, particularly in social insects.

Methods

Camponotus fellah: sampling sites and culture

Camponotus ants develop by complete metamorphosis, like all hymenopterans, going through stages of the egg, larva, pupa, and adult worker or reproductive. Pupae exist in conspicuous silk cocoons. Newly fecundated females start a new colony, caring for their first brood of larvae until they develop into workers, which then begin to forage for food. Founding queens of C. fellah were collected in Tel-Aviv in March 2006 and 2007. Colonies were kept in plastic containers (20 × 20 × 10 cm) with plaster nests in a climate chamber (constant temperature of 28°C, 12 h light per day), and were fed twice a week with Tenebrio molitor larvae and commercial honey solution (BeeHappy®, France). In 2006 and 2007 we used 10 control colonies (fed with Tenebrio and honey) and 10 treated colonies (fed with Tenebrio and honey in the first week, and Tenebrio larvae and honey solution containing 1% of the antibiotic Rifampin the second week and after). In previous studies on other Camponotus species [30] Rifampin was shown to reduce the number of bacteria without increasing mortality and did not cause damage to the ant midgut tissues. The treatment was maintained during three months.

Because the occurrence of Wolbachia is widespread in ants [31] and these symbiotic bacteria can have negative effects on immunity-related traits of insects [32], their incidence was checked in the C. fellah colonies studied, using two pairs of primers based on Wolbachia ftsZ sequences [31], so as to amplify A and B-group Wolbachia specific product [31]. No incidence of Wolbachia was detected.

Symbiont identification

Symbiont identification was based on sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene and Fluorescent in situ hybridization. The 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the previously described primers SL (TTGGGATCCAGAGTTTGATCATGGCTCAGAT) and SR (CACGAATTCTACCTTGTTACGACTTCACCCC) [33]. The PCR reactions were performed in a total volume of 25 μl containing 2.5 mM dNTPs, 7.5 mM MgCl2, 5 pmol each oligonucleotide and 2.5 U/μl Taq DNA polymerase (GoldStar®). Amplification was performed in an Eppendorf thermocycler according to the following conditions: 30 s denaturation at 94°C, 30 s primers annealing at 55 °C and 1.5 min primer extension at 72°C, running 35 cycles. The amplified DNA fragment of approximately 1,550 bp was purified using a QIAquick PCR purification Kit (Qiagen) and directly sequenced using the ABI PRISM™ dye terminator cycle. The sequencing reactions were performed using the SL and SR primers and using the two internal primers sequences CampL (5'-GAATTACTGGGCGTAAAGAGT-3') and CampR (5'-GGAACGTATTCACCG TGAC-3'). Additionally, two reverse primers were designed to complete the sequences: P1rev(5'-CTCTCAGACCAGCTAAGGAT-3') and P2rev(5'-ACCGCTACACCTGGAATTCT-3').

The oligonucleotides used for in situ hybridization were described previously. Bacteriocytes were visualized by FISH with oligonucleotide probes Eub338 (5'-GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT-3') [34], targeting a conserved region of the eubacterial 16S rRNA, and with Bfl172 (5'-CCTATCTGGGTTCATCCAATGGCATAAGGC-3'), targeting a 16S rRNA region specific for B. floridanus [33]. Probes were labelled with the fluorescent dyes Cy3 or FITC at the 5' end (MWG-BIOTECH AG, Ebersberg, Germany). For protocol process details see [2]. The ovaries of three years old queen were dissected, fixed and hybridized like the midguts. The slides were analyzed with a Leica DMR microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and pictures were taken with a RT Slider digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments Inc., Sterling Heights, MI, USA).

Evaluation of colony development

Colonies collected in 2006 were used to evaluate control colonies versus treated colonies development. Over a period of seven months (including the first three months of antibiotic treatment) the number of brood (larvae and pupae) and workers in each colony were counted each month, during seven months.

Encapsulation rate assay

Encapsulation followed by melanisation is an efficient innate immune response against parasites. We can trigger this response by inserting an inert antigen, like nylon filament. To measure the ant immune response, an encapsulation test was performed by inserting a 1.5 mm-long piece of nylon monofilament (0.12 mm diameter) in the pleural membrane between the second and third tergite. This procedure was carried out on three workers from each colony, with a total of 30 workers for each group, based on the procedures adopted by Rantala & Kortet [35]. Twenty four hours after, the implants were removed from the haemocoel and placed on a glass slide to be mounted into Clarion™ medium. The filament was examined under a light microscope and photographed using a digital camera (Olympus DP50). The mean grey value of the whole implant was measured using the ImageJ 1.37v software. We assumed that the darkest grey received the highest encapsulation rate (total black). The background grey value was subtracted to correct the values of the implants. The midgut of each worker was dissected in sterile PBS (137 mM NaCl-2.7 mM KCl-4.3 mM sodium phosphate-1.4 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.2) and conserved in tubes independently at -20C° for quantitative PCR.

Assessing antibiotic treatment effects

Antibiotc treatments effects were assessed by two different and complementary techniques: Real time qPCR and Fluorescent in situ hybridization (Fish).

Real time qPCR

DNA was isolated from the whole midgut of individual workers that were previously tested for encapsulation rate (see Encapsulation assays) using DNA extraction commercial kit (Gentra Systems Puregene©, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to manufacturer's recommendations then resuspended in 20 μl double distilled water. Quantitative PCR reactions were performed in presence of SYBR Green on ABI Prism 7000 gene expression system according to the manufacturers' instructions (Applied Biosystems, France) using 5-time dilution of each DNA. Bacteria were quantified using specific primers designed to amplified a 16S rDNA 150-bp-length fragment of Blochmannia (16SFor 5'-AGAATTCCAGGTGTAGCGGTG-3' and 16SRev 5'-TACGGCATGGACTACCAGGG-3'). Ant DNA were quantified using specific primers designed to amplify a 18S rDNA 150-bp-length fragment (18SFor 5'-TTAGAGTGCTTAAAGCAGGC-3' and 18SRev 5'-ACCTCTAACGTCGCAATACG-3'). These primers had been efficiently used in another study with Blochmannia floridanus [14]. The 18S rRNA ant gene copy number was used so as to normalize each dissected sample with the same quantity of ant DNA material. This gene was first specifically cloned and sequenced. Then real-time PCR specific primers (18SFor 5'-TTAGAGTGCTTAAAGCAGGC-3' and 18SRev 5'-ACCTCTAACGTCGCAATACG-3') were design based on the sequence and used to generate by classic PCR a 18S rDNA specific amplicon used to establish a standard curve expressing the Cycle Threshold (Ct) versus the logarithm of the copy number of 18S rDNA purified PCR products. These specific primers were also used to amplify 18S rDNA using DNA extracted from dissected samples. The exact copy number of 18S rDNA was established based on the experimentally obtained Ct value and the standard curve. This value was used to correct the calculated copy number of bacterial 16S rDNA.

Fluorescent In Situ hybridisation (FISH)

Bacteriocyte were visualized by FISH with oligonucleotide probes as previously described in the method topic "Symbiont identification".

References

Wernegreen JJ: Endosymbiosis: Lessons in conflict resolution. Plos Biol. 2004, 2: 307-311. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020068.

Feldhaar H, Straka J, Krischke M, Berthold K, Stoll S, Mueller MJ, Gross R: Nutritional upgrading for omnivorous carpenter ants by the endosymbiont Blochmannia. BMC Biol. 2007, 5: 48-10.1186/1741-7007-5-48.

Dethlefsen L, McFall-Ngai M, Relman DA: An ecological and evolutionary perspective on human-microbe mutualism and disease. Nature. 2007, 449: 811-818. 10.1038/nature06245.

Margulis L, Fester R: Symbiosis as a source of evolutionary innovation-speciation and morphogenesis. 1991, Cambridge, MIT Press

Moran NA: Symbiosis as an adaptive process and source of phenotypic complexity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007, 104: 8627-8633. 10.1073/pnas.0611659104.

Vautrin E, Genieys S, Charles S, Vavre F: Do vertically transmitted symbionts co-existing in a single host compete or cooperate? A modelling approach. J Evol Biol. 2008, 21: 145-161.

Lombardo M: Access to mutualistic endosymbiotic microbes: an underappreciated benefit of group living. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2008, 62: 479-497. 10.1007/s00265-007-0428-9.

Krause J, Ruxton GD: Living in groups. 2002, New York, Oxford University Press

Cremer S, Armitage SAO, Schmid-Hempel P: Social Immunity. Curr Biol. 2007, 17: R693-R702. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.008.

Degnan PH, Lazarus AB, Brock CD, Wernegreen JJ: Host-symbiont stability and fast evolutionary rates in an ant-bacterium association: Cospeciation of Camponotus species and their endosymbionts, Candidatus Blochmannia. Syst Biol. 2004, 53: 95-110. 10.1080/10635150490264842.

Gaudermann P, Vogl I, Zientz E, Silva FJ, Moya A, Gross R, Dandekar T: Analysis of and function predictions for previously conserved hypothetical or putative proteins in Blochmannia floridanus. Bmc Microbiol. 2006, 6: 1-10.1186/1471-2180-6-1.

Degnan PH, Lazarus AB, Wernegreen JJ: Genome sequence of Blochmannia pennsylvanicus indicates parallel evolutionary trends among bacterial mutualists of insects. Genome Res. 2005, 15: 1023-1033. 10.1101/gr.3771305.

Gil R, Silva FJ, Zientz E, Delmotte F, Gonzalez-Candelas F, Latorre A, Rausell C, Kamerbeek J, Gadau J, Holldobler B: The genome sequence of Blochmannia floridanus: Comparative analysis of reduced genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003, 100: 9388-9393. 10.1073/pnas.1533499100.

Zientz E, Beyaert N, Gross R, Feldhaar H: Relevance of the endosymbiosis of Blochmannia floridanus and carpenter ants at different stages of the life cycle of the host. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006, 72: 6027-6033. 10.1128/AEM.00933-06.

Wernegreen JJ, Degnan PH, Lazarus AB, Palacios C, Bordenstein SR: Genome evolution in an insect cell: Distinct features of an ant-bacterial partnership. Biol Bull. 2003, 204: 221-231. 10.2307/1543563.

Sauer C, Stackebrandt E, Gadau J, Holldobler B, Gross R: Systematic relationships and cospeciation of bacterial endosymbionts and their carpenter ant host species: proposal of the new taxon Candidatus Blochmannia gen. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000, 50: 1877-1886.

Moran NA: Symbiosis. Curr Biol. 2006, 16: R866-R871. 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.019.

Oliver KM, Russell JA, Moran NA, Hunter MS: Facultative bacterial symbionts in aphids confer resistance to parasitic wasps. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003, 100: 1803-1807. 10.1073/pnas.0335320100.

Hedges LM, Brownlie JC, O'Neill SL, Johnson KN: Wolbachia and virus protection in insects. Science. 2008, 322: 702-10.1126/science.1162418.

Kaltenpoth M, Gottler W, Herzner G, Strohm E: Symbiotic bacteria protect wasp larvae from fungal infestation. Curr Biol. 2005, 15: 475-479. 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.084.

Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR: Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007, 73: 5261-5267. 10.1128/AEM.00062-07.

Dedeine F, Vavre F, Fleury F, Loppin B, Hochberg ME, Bouletreau M: Removing symbiotic Wolbachia bacteria specifically inhibits oogenesis in a parasitic wasp. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001, 98: 6247-6252. 10.1073/pnas.101304298.

Pannebakker BA, Loppin B, Elemans CPH, Humblot L, Vavre F: Parasitic inhibition of cell death facilitates symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007, 104: 213-215. 10.1073/pnas.0607845104.

Dillon RJ, Vennard CT, Buckling A, Charnley AK: Diversity of locust gut bacteria protects against pathogen invasion. Ecol Lett. 2005, 8: 1291-1298. 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00828.x.

Gilturnes MS, Hay ME, Fenical W: Symbiotic marine-bacteria chemically defend crustacean embryos from a pathogenic fungus. Science. 1989, 246: 116-118. 10.1126/science.2781297.

Hölldobler B, Wilson EO: The ants. 1990, Cambridge, Harvard University Press

Feener JDH: Is the assembly of ant communities mediated by parasitoids?. Oikos. 2000, 90: 79-88. 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.900108.x.

Wernegreen JJ, Lazarus AB, Degnan PH: Small genome of Candidatus Blochmannia, the bacterial endosymbiont of Camponotus, implies irreversible specialization to an intracellular lifestyle. Microbiology. 2002, 148 (Pt 8): 2551-2556.

Wernegreen JJ: Genome evolution in bacterial endosymbionts of insects. Nat Rev Genet. 2002, 3: 850-861. 10.1038/nrg931.

Sauer C, Dudaczek D, Holldobler B, Gross R: Tissue localization of the endosymbiotic bacterium "Candidatus Blochmannia floridanus" in adults and larvae of the carpenter ant Camponotus floridanus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002, 68: 4187-4193. 10.1128/AEM.68.9.4187-4193.2002.

Wenseleers T, Ito F, van Borm S, Huybrechts R, Volckaert F, Billen J: Widespread occurrence of the micro-organism Wolbachia in ants. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1998, 265: 1447-1452. 10.1098/rspb.1998.0456.

Fytrou A, Schofield PG, Kraaijeveld AR, Hubbard SF: Wolbachia infection suppresses both host defence and parasitoid counter-defence. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006, 273: 791-796. 10.1098/rspb.2005.3383.

Schröder D, Deppisch H, Obermayer M, Krohne G, Stackebrandt E, Hölldobler B, Goebel W, Gross R: Intracellular endosymbiotic bacteria of Camponotus species (carpenter ants): systematics, evolution and ultrastructural characterization. Mol Microbiol. 1996, 21: 479-489. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02557.x.

Amann RI, Krumholz L, Stahl DA: Fluorescent-oligonucleotide probing of whole cells for determinative, phylogenetic, and environmental-studies in microbiology. J Bacteriol. 1990, 172: 762-770.

Rantala MJ, Kortet R: Courtship song and immune function in the field cricket Gryllus bimaculatus. Biol J Linn Soc Lond. 2003, 79: 503-510. 10.1046/j.1095-8312.2003.00202.x.

Acknowledgements

We thank Danielle Mersch and Stephane Dorsaz from Lausanne University and Abraham Hefetz from Tel-Aviv University for collection of the mated queen ants. Heike Feldhaar and Sascha Stoll from Wurzburg University aided us on FISH and Quantitative PCR techniques. Terezinha Della Lucia and Elisabeth Huguet aided us to improve the writing. The first author was financially supported by grants from the Capes (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior-Brasil).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

DJS and AL planned and coordinated the study. AB and DJS conducted the quantification of bacteria by q-PCR and FISH. DJS and DD identified the Blochmannia. All authors wrote the article.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

de Souza, D.J., Bézier, A., Depoix, D. et al. Blochmannia endosymbionts improve colony growth and immune defence in the ant Camponotus fellah. BMC Microbiol 9, 29 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-9-29

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-9-29