Abstract

Background

Mycobacterium abscessus group includes antibiotic-resistant, opportunistic mycobacteria that are responsible for sporadic cases and outbreaks of cutaneous, pulmonary and disseminated infections. However, because of their close genetic relationships, accurate discrimination between the various strains of these mycobacteria remains difficult. In this report, we describe the development of a multispacer sequence typing (MST) analysis for the simultaneous identification and typing of M. abscessus mycobacteria. We also compared MST with the reference multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) typing method.

Results

Based on the M. abscessus CIP104536T genome, eight intergenic spacers were selected, PCR amplified and sequenced in 21 M. abscessus isolates and analysed in 48 available M. abscessus genomes. MST and MLSA grouped 37 M. abscessus organisms into 12 and nine types, respectively; four formerly “M. bolletii” organisms and M. abscessus M139 into three and four types, respectively; and 27 formerly “M. massiliense” organisms grouped into nine and five types, respectively. The Hunter-Gaston index was off 0.912 for MST and of 0.903 for MLSA. The MST-derived tree was similar to that based on MLSA and rpoB gene sequencing and yielded three main clusters comprising each the type strain of the respective M. abscessus sub-species. Two isolates exhibited discordant MLSA- and rpoB gene sequence-derived position, one isolate exhibited discordant MST- and rpoB gene sequence-derived position and one isolate exhibited discordant MST- and MLSA-derived position. MST spacer n°2 sequencing alone allowed for the accurate identification of the different isolates at the sub-species level.

Conclusions

MST is a new sequencing-based approach for both identifying and genotyping M. abscessus mycobacteria that clearly differentiates formerly “M. massiliense” organisms from other M. abscessus subsp. bolletii organisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mycobacterium abscessus mycobacteria are increasingly being cultured from respiratory tract specimens collected from patients with chronic pulmonary diseases, including cystic fibrosis [1–9]. These mycobacteria are also responsible for skin and soft-tissue infections following surgical and cosmetic practices [10–12] and catheter-related bacteremia [13, 14]. These infections are particularly critical for immune-compromised patients and may be fatal [15]. Water is suspected as a source of infection, as M. abscessus mycobacteria have been isolated from tap water [16]. Moreover, M. abscessus mycobacteria have been shown to be resistant to water-borne free-living amoebae [17, 18]. M. abscessus infections are also associated with treatment failure owing, due to the natural broad-spectrum resistance to antibiotics in addition to acquired resistance, with subtle differences in the antibiotic susceptibility pattern being observed among isolates [19].

Indeed, M. abscessus is comprised of a heterogeneous group of mycobacteria currently classified into M. abscessus subsp. abscessus and M. abscessus subsp. bolletii[20, 21], with the later subspecies accommodating mycobacteria previously identified as “Mycobacterium bolletii” or “Mycobacterium massiliense” [18, 22]. However, these organisms are nearly indistinguishable using phenotypic tests including the mycolic acid pattern analysis and share 100% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity [20]. They were initially differentiated on the basis of >3% rpoB gene sequence divergence and different antimicrobial susceptibility patterns [23, 24]. Nevertheless, confusing results based on rpoB sequencing have been reported [21], and combining sequencing of the rpoB, hsp65 and secA genes has been advocated for the optimal identification of the M. abscessus mycobacteria [25].

To further decrypt the diversity and genetic relationships among M. abscessus organisms, we investigated a collection of reference, sequenced genomes and clinical M. abscessus isolates using multispacer sequence typing (MST), which is a sequencing-based approach previously used for the species identification and genotyping of Mycobacteria, including Mycobacterium avium[26] and Mycobacterium tuberculosis[27] and non-mycobacterial pathogens, such as Yersinia pestis[28], Rickettsia prowazekii[29] and Bartonella quintana[30]. This approach was here compared with multilocus sequence analaysis which relies the sequencing of 5–8 genes (21, 25), and rpoB genes sequencing (23, 24).

Methods

Bacterial isolates

Reference M. abscessus CIP104536T, M. abscessus DSMZ44567 (German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, Braunschweig, Germany), M. abscessus subsp. bolletii CIP108541T (herein referred as “M. bolletii”) and M. abscessus subsp. bolletii CIP108297T (herein referred as “M. massiliense” [23]) were used in this study. In addition, a collection of 17 M. abscessus clinical isolates from the mycobacteria reference laboratory of the Méditerranée Infection Institute, Marseille, France were also studied (Table 1). All of the mycobacteria were grown in 7H9 broth (Difco, Bordeaux, France) enriched with 10% OADC (oleic acid, bovine serum albumin, dextrose and catalase) at 37°C. As for the identification, DNA extraction and rpoB partial sequence-based identification were performed using the primers MYCOF and MYCOR2 (Table 1) as previously described [24]. In addition, the rpoB gene sequence retrieved from 48 M. abscessus sequenced genomes was also analysed (Additional file 1) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Reference MLSA typing

Fragments from five housekeeping genes argH (argininosuccinate lyase), cya (adenylate cyclase), murC (UDP N-acetylmuramate-L-Ala ligase, pta (phosphate acetyltransferase) and purH (phoshoribosylminoimiazolcarboxylase ATPase subunit) were amplified using the sets of primers as previously described (21). The sequences of each one of these five housekeeping genes retrieved from 48 M. abscessus sequenced genomes, were also included in the MLSA analysis (Additional file 1).

MST analysis

Sequences of the whole intergenic spacers were extracted from the reference M. abscessus CIP104536T (ATCC19977) genome (GenBank accession CU458896.1) using the perl script software and a total of 8 spacers with a 200-700-bp sequence size were further used in analysis. For each of these 8 spacers, specific PCR primers were designed using Primer3 software v 0.4.0 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3) and tested in silico for specificity using BLAST software (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The PCR conditions were first optimized using DNA extracted from the reference M. abscessus, “M. bolletii” and “M. massiliense” isolates before analysis of DNA extracted from the 17 clinical isolates (Table 1). The PCR amplifications were performed in a 50 μl PCR mixture containing 5 μl 10x buffer (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France), 200 mM each dNTP, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1.25 U HotStarTaq polymerase (Qiagen), 1 μl each primer (10 pM), 33 μl nuclease-free water and 5 μl DNA template. The amplification program consisted of an initial 15 min denaturation step at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 60°C and 1 min at 72°C; the amplification was completed by a final 5-min elongation step at 72°C. Negative controls consisting of PCR mixture without DNA template were included in each PCR run. The products were visualized by gel electrophoresis, purified using a MultiScreen PCR filter plate (Millipore, Molsheim, France) and sequenced in both directions using the BigDye Terminator sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Villebon-sur-Yvette, France), as previously described [27]. The sequences were edited using the ChromasPro software (version 1.42; Technelysium Pty Ltd), aligned using Clustal W (MEGA 5 software) and compared with the reference M. abscessus ATCC 19977 sequences (GenBank accession CU458896.1). For MST and MLSA discrimination power was calculated using the Hunter-Gaston Index [31]:

where D is the numerical index of discrimination, N is the total number of isolates in the sample population, s is the total number of different types and nj is the number of isolates belonging to the jth type.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic trees were constructed based on rpoB gene, concatenated MLSA genes, concatenated spacers and MST spacer n°2 sequences using the neighbor–joining method with Kimura’s two-parameter (K2P) distance correction model with 1000 bootstrap replications in the MEGA version 5 software package [32]. The rpoB gene sequence-based tree was rooted using M. chelonae strain CIP 104535T and M. immunogenum strain CIP 106684TrpoB gene sequences. A heatmap was constructed using the R statistical software based on the spacer profile as a distance matrix.

Results and discussion

rpoB identification and rpoB tree

The identification of M. abscessus CIP104536T, M. abscessus DSMZ44567, M. bolletii CIP108541T and M. massiliense CIP108297T was confirmed by partial rpoB sequencing. The sequences were deposited in the GenBank database (GenBank accession: KC352778 - KC352795). Isolates P1, P2.1, P2.2, P2.3, P2.4, P2.5, P3.1, P3.2, P4, P5, P6, P7 and P8 exhibited 99% rpoB sequence similarity with M. abscessus ATCC19977T and were identified as M. abscessus. Isolates P9 and P10 exhibited 99% rpoB sequence similarity with “M. bolletii” CIP108541T and were identified as “M. bolletii” whereas isolate P11 exhibited 99% rpoB sequence similarity with “M. massiliense” CIP108297T and was identified as “M. massiliense”. A total of 23 M. abscessus sequenced genomes were identified as M. abscessus since they exhibited 98 to 100% similarity with the M. abscessus type strain rpoB partial gene sequence. M. abscessus M24 shared 99% similarity with the M. bolletii type strain partial rpoB gene sequence. A total of 26 M. abscessus and “M. massiliense” sequenced genomes shared 99% to 100% similarity with “M. massiliense” partial rpoB gene sequence. The tree built from 69 partial rpoB gene sequences showed three distinct groups, each comprising the type strain (Figure 1a).

Reference MLSA analysis

Fragments for the expected size were amplified and sequenced for the five MLSA genes. The sequences were deposited in the GenBank database (GenBank accession: KC352742 - KC352759, KC352760 - KC352777, KC352796 - KC352813, KC352814 - KC352831, KC352832 - KC352849). Concatenation of the five sequences yielded a total of 19 different types, including 9 types for 37 M. abscessus organisms, four types for 4 “M. bolletii” organisms and M. abscessus M139 and five types for 27 “M. massiliense” organisms. The Hunter-Gaston Index for MLSA was of 0.903. The MLSA tree based on the five gene concatened sequences showed three principal clusters, i.e. a M. abscessus cluster, a “M. bolletii” cluster and a “M. massiliense” cluster (Figure 1b). Latter cluster comprised of five sub-clusters with “M. massiliense” type strain and P11 strain sub-clustering together close to M. abscessus 5S strain. Also, MLSA-derived tree clustered M. abscessus M139 strain and P5 strain respectively identified as “M. massiliense”, close to the “M. bolletii” whereas both strains clustered with M. abscessus in the rpoB gene sequence-derived tree.

MST analysis

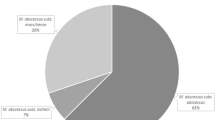

Analysis of the reference M. abscessus ATCC 19977 complete genome sequence yielded 3538 intergenic spacers with > 300 spacers were 200–700 bp in length. Successful PCR sequencing was achieved for 8 spacers in all the isolates studied; the sequences were deposited in the GenBank database (GenBank accession: KC352850 - KC352890). In M. abscessus isolates, including the 37 sequenced genomes, the spacer sequence variability was generated by one to 12 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (spacers n°1 and n°8), one to 18 SNPs and one to two nucleotide deletions (spacer n°2), one to two SNPs (spacers n°3 and n°7) and nucleotide insertion (spacers n°2 and n°5). In “M. bolletii” isolates, the spacer sequence polymorphisms were generated by one SNP for spacer n°1, two SNPs and one deletion for spacer n°2, two SNPs for spacer n°3 and nine SNPs for spacer n°7. In “M. massiliense” isolates, including 28 sequenced genomes, the spacer sequence polymorphism were generated by nine SNPs and one insertion (spacer n°1), one insertion (spacer n°3), five SNPs and two insertions (spacer n°4), one SNP (spacer n°5) and two SNPs (spacer n°7). Concatenation of the eight spacer sequences yielded a total of 24 types, with the 37 M. abscessus organisms grouped into 12 spacer types, four formerly “M. bolletii” organisms grouped into three spacer types and 28 formerly “M. massiliense” organisms grouped into nine spacer types. This yielded a Hunger-Gaston Index of 0.912. Spacer n°5 was found to be the most variable of the eight spacers under study, exhibiting 13 different alleles (Table 2). When combining the eight spacer sequences, a unique MST profile for each reference isolate was obtained, i.e., MST1 and MST2 for M. abscessus CIP104536T and M. abscessus DSMZ44567 respectively, MST13 for “M. bolletii” CIP108541T and MST16 for “M. massiliense” CIP108297T. At the sequence level, we found that MST1 and MST2 genotypes differ by at most nine SNPs, whereas MST1 differed from MST13 by up to 18 SNPs, one insertion and two deletions and from MST16 by 14 SNPs, 11 deletions and two insertions (supplementary material). The 17 clinical M. abscessus isolates were grouped into eight MST types, named MST1 to MST8, with five M. abscessus isolates exhibiting the M. abscessus CIP104536T MST1 genotype and one isolate (P1 strain) exhibiting the M. abscessus DSMZ44567 MST2 genotype. The P9 “M. bolletii” clinical isolate yielded the MST13 genotype in common with the reference “M. bolletii” CIP108541T, whereas the P10 “M. bolletii” clinical isolate yielded a unique MST14 genotype that differ from MST13 by two SNPs in spacer n°1. M. abscessus M24 yielded the MST15 and differed from MST13 by four polymorphic spacers. In “M. massiliense” nine different profiles were generated MST 16 to MST24. The P11 “M. massiliense” clinical isolate shared the MST16 genotype with the reference “M. massiliense” CIP108297T. “M. massiliense” 2B isolate, “M. massiliense” 1S isolate and “M. massiliense” M18 isolate shared the same MST profile (MST17). M. abscessus 5S isolate exhibited the MST21 profile.

MST based tree and comparaison with rpoB identification and MLSA analysis

The MST-phylogenetic tree clustered isolates from patients P1 to P8 with M. abscessus reference strain, isolates from P9 and P10 with “M. bolletii” and isolate from P11 with “M. massiliense”, in agreement with their rpoB sequence-based identification and MLSA analysis (Figure 1c). The MST, MLSA and rpoB phylogenetic trees separated the M. abscessus isolates into three principal clusters depicted by M. abscessus, “M. bolletii” and “M. massiliense” isolates (Figure 1a, b and c). However, MST resolved “M. bolletii” cluster into two sub-clusters formed by isolate P5 and all of the other M. bolletii isolates with a 76% bootstrap value, wich is discordant with MLSA and rpoB based tree. Each cluster or sub-cluster of the M. abscessus isolates corresponded to different genotypes. The “M. massiliense” cluster was more disperse and divided into six sub-clusters with isolate P11 and “M. massiliense” type strain sub-clustering alone. The results of this analysis were consistent for 67 isolates and inconsistent for two isolates P5 and M. abscessus M139. A heatmap incorporating all spacer patterns into a matrix further demonstrated that spacer n°2 was the most discriminating spacer (Figure 2). Hence, the tree based on the spacer n°2 sequence also discriminated the three M. abscessus, “M. bolletii” and “M. massiliense” clusters (Figure 3). This discrimination potential makes spacer n°2 a useful new tool for the accurate identification of M. abscessus subspecies. Furthermore, these data indicated that it was readily possible to discriminate isolates that would have been identified as “M. bolletii” [26] or “M. massiliense” [23] using a previous taxonomy proposal and are now grouped as M. abscessus subsp. bolletii according to a recent taxonomy proposal [20, 21].

Conclusion

We herein developed a sequencing-based MST genotyping technique that allows the accurate identification and discrimination of M. abscessus mycobacteria. Therefore, MST could be added to the panel of molecular methods currently available for genotyping M. abscessus mycobacteria, with the advantages that MST is a PCR and sequencing-based technique, thereby providing a robust and accurate result without requiring a high DNA concentration and purity, as is the case for pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) [5] and randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) [33]. Furthermore, MST targets intergenic spacers, which undergo less evolutionary pressure and are thus more variable than the housekeeping genes targeted in multilocus sequence typing [21]. Also, MST incorporating sequencing is an open approach to described new genotypes more versatile than counting the number of tandem repeats [34]. We propose that MST could be incorporated into a polyphasic molecular approach to resolve the phylogenetic relationships of difficult-to-identify M. abscessus isolates [35]. Combining MST data with phylogenetic analyses clearly indicated that M. abscessus heterogeneity spans beyond the current two M. abscessus subspecies, as two “M. massiliense” isolates were readily discriminated from the other “M. bolletii” isolates [21]. These data, therefore, question the current nomenclature of M. abscessus mycobacteria, which incorporates mycobacteria previously recognized as “M. bolletii” and “M. massiliense” as “M. abscessus subsp. bolletii”. The data presented here indicate that this nomenclature masks the underlying diversity of M. abscessus mycobacteria, potentially hampering the recognition of microbiological, epidemiological and clinical particularities that are linked to each subspecies. The elevation of “M. massiliense” as a new M. abscessus subspecies would accommodate the data produced in the present study [24].

References

Griffith DE, Girard WM, Wallace RJ: Clinical features of pulmonary disease caused by rapidly growing mycobacteria. An analysis of 154 patients. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993, 147: 1271-1278.

Pierre-Audigier C, Ferroni A, Sermet-Gaudelus I, Le Bourgeois M, Offredo C, Vu-Thien H, Fauroux B, Mariani P, Munck A, Bingen E, Guillemot D, Quesne G, Vincent V, Berche P, Gaillard JL: Age-related prevalence and distribution of nontuberculous mycobacterial species among patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005, 43: 3467-3470. 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3467-3470.2005.

Olivier KN, Weber DJ, Wallace RJ, Faiz AR, Lee JH, Zhang Y, Brown-Elliot BA, Handler A, Wilson RW, Schechter MS, Edwards LJ, Chakraborti S, Knowles MR, et al: Nontuberculous mycobacteria. I: multicenter prevalence study in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003, 167: 828-834. 10.1164/rccm.200207-678OC.

Chalermskulrat W, Sood N, Neuringer IP, Hecker TM, Chang L, Rivera MP, Paradowski LJ, Aris RM: Non-tuberculous mycobacteria in end stage cystic fibrosis: implications for lung transplantation. Thorax. 2006, 61: 507-513. 10.1136/thx.2005.049247.

Jönsson BE, Gilljam M, Lindblad A, Ridell M, Wold AE, Welinder-Olsson C: Molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium abscessus, with focus on cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2007, 45: 1497-1504. 10.1128/JCM.02592-06.

Levy I, Grisaru-Soen G, Lerner-Geva L, Kerem E, Blau H, Bentur L, Aviram M, Rivlin J, Picard E, Lavy A, Yahav Y, Rahav G: Multicenter cross-sectional study of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections among cystic fibrosis patients. Israel Emerg Infect Dis. 2008, 14: 378-384. 10.3201/eid1403.061405.

Griffith DE: Emergence of nontuberculous mycobacteria as pathogens in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003, 167: 810-812. 10.1164/rccm.2301001.

Roux AL, Catherinot E, Ripoll F, Soismier N, Macheras E, Ravilly S, Bellis G, Vibet MA, Le Roux E, Lemonnier L, Gutierrez C, Vincent V, Fauroux B, Rottman M, Guillemot D, Gaillard JL, Jean-Louis Herrmann for the OMA Group: Multicenter study of prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacteria in patients with cystic fibrosis in france. J Clin Microbiol. 2009, 47: 4124-4128. 10.1128/JCM.01257-09.

Uyan ZS, Ersu R, Oktem S, Cakir E, Koksalan OK, Karadag B, Karakoc F, Dagli E: Mycobacterium abscessus infection in a cystic fibrosis patient: a difficult to treat infection. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010, 14: 250-251.

Furuya EY, Paez A, Srinivasan A, Cooksey R, Augenbraun M, Baron M, Brudney K, Della-Latta P, Estivariz C, Fischer S, Flood M, Kellner P, Roman C, Yakrus M, Weiss D, Granowitz EV: Outbreak of mycobacterium abscessus wound infections among “lipotourists” from the United States who underwent abdominoplasty in the Dominican Republic. Clin Infect Dis. 2008, 46: 1181-1188. 10.1086/529191.

Koh SJ, Song T, Kang YA, Choi JW, Chang KJ, Chu CS, Jeong JG, Lee JY, Song MK, Sung HY, Kang YH, Yim JJ: An outbreak of skin and soft tissue infection caused by Mycobacterium abscessus following acupuncture. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010, 16: 895-901.

Viana-Niero C, Lima KV, Lopes ML, Rabello MC, Marsola LR, Brilhante VC, Durham AM, Leão SC: Molecular characterization of Mycobacterium massiliense and Mycobacterium bolletii in isolates collected from outbreaks of infections after laparoscopic surgeries and cosmetic procedures. J Clin Microbiol. 2008, 46: 850-855. 10.1128/JCM.02052-07.

Petrini B: Mycobacterium abscessus: an emerging rapid-growing potential pathogen. APMIS. 2006, 114: 319-328. 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2006.apm_390.x.

Hayes D: Mycobacterium abscessus and other nontuberculous mycobacteria: evolving respiratory pathogens in cystic fibrosis: a case report and review. Southern Med J. 2005, 98: 657-661. 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000163311.70464.91.

Sanguinetti M, Ardito F, Fiscarelli E, La Sorda M, D’argenio P, Ricciotti G, Fadda G: Fatal pulmonary infection due to multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus in a patient with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2001, 39: 816-819. 10.1128/JCM.39.2.816-819.2001.

Shin JH, Lee HK, Cho EJ, Yu JY, Kang YH: Targeting the rpoB gene using nested PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism for identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria in hospital tap water. J Microbiol. 2008, 46: 608-614. 10.1007/s12275-008-0102-6.

Huang WC, Chiou CS, Chen JH, Shen GH: Molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium abscessus infections in a subtropical chronic ventilatory setting. J Med Microbiol. 2010, 59: 1203-1211. 10.1099/jmm.0.020586-0.

Adékambi T, Ben Salah I, Khlif M, Raoult D, Drancourt M: Survival of environmental mycobacteria in Acanthamoeba polyphaga. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006, 72: 5974-5981. 10.1128/AEM.03075-05.

Koh WJ, Jeon K, Lee NY, Kim BJ, Kook YH, Lee SH, Park YK, Kim CK, Shin SJ, Huitt GA, Daley CL, Kwon OJ: Clinical significance of differentiation of Mycobacterium massiliense from Mycobacterium abscessus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011, 183: 405-410. 10.1164/rccm.201003-0395OC.

Leao SC, Tortoli E, Viana-Niero C, Ueki SY, Lima KV, Lopes ML, Yubero J, Menendez MC, Garcia MJ: Characterization of mycobacteria from a major Brazilian outbreak suggests that revision of the taxonomic status of members of the Mycobacterium chelonae-M. abscessus group is needed. J Clin Microbiol. 2009, 47: 2691-2698. 10.1128/JCM.00808-09.

Macheras E, Roux AL, Bastian S, Leão SC, Palaci M, Sivadon-Tardy V, Gutierrez C, Richter E, Rüsch-Gerdes S, Pfyffer G, Bodmer T, Cambau E, Gaillard JL, Heym B: Multilocus sequence analysis and rpoB sequencing of Mycobacterium abscessus (sensu lato) strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2011, 49: 491-499. 10.1128/JCM.01274-10.

Adékambi T, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Greub G, Gevaudan MJ, La Scola B, Raoult D, Drancourt M: Amoebal coculture of “mycobacterium massiliense” sp. nov. From the sputum of a patient with hemoptoic pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol. 2004, 42: 5493-5501. 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5493-5501.2004.

Adékambi T, Drancourt M: Dissection of phylogenetic relationships among 19 rapidly growing Mycobacterium species by 16S rRNA, hsp65, sodA, recA and rpoB gene sequencing. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004, 54: 2095-2105. 10.1099/ijs.0.63094-0.

Adékambi T, Berger P, Raoult D, Drancourt M: rpoB gene sequence-based characterization of emerging non-tuberculous mycobacteria with descriptions of Mycobacterium bolletii sp. nov., Mycobacterium phocaicum sp. nov. and Mycobacterium aubagnense sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006, 56: 133-143. 10.1099/ijs.0.63969-0.

Macheras E, Roux AL, Ripoll F, Sivadon-Tardy V, Gutierrez C, Gaillard JL, Heym B: Inaccuracy of single-target sequencing for discriminating species of the Mycobacterium abscessus group. J Clin Microbiol. 2009, 47: 2596-2600. 10.1128/JCM.00037-09.

Cayrou C, Turenne C, Behr MA, Drancourt M: Genotyping of Mycobacterium avium complex organisms using multispacer sequence typing. Microbiol. 2010, 156: 687-694. 10.1099/mic.0.033522-0.

Djelouadji Z, Arnold C, Gharbia S, Raoult D, Drancourt M: Multispacer sequence typing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotyping. PLoS One. 2008, 3: e2433-10.1371/journal.pone.0002433.

Drancourt M, Roux V, Dang LV, Tran-Hung L, Castex D, Chenal-Francisque V, Ogata H, Fournier PE, Crubézy E, Raoult D: Genotyping, Orientalis-like Yersinia pestis, and Plague Pandemics. Emer Infect Dis. 2004, 10: 1585-1592. 10.3201/eid1009.030933.

Wenjun LI, Mouffok N, Rovery C, Parola P, Raoult D: Genotyping Rickettsia conorii detected in patients with Mediterranean spotted fever in Algeria using multispacer typing (MST). Clin Microbiol Inf. 2009, 15: 281-283.

Foucault C, La Scola B, Lindroos H, Andersson SGE, Raoult D: Multispacer typing technique for sequence-based typing of Bartonella Quintana. J Clin Microbiol. 2005, 43: 41-48. 10.1128/JCM.43.1.41-48.2005.

Hunter PR, Gaston MA: Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson’s index of diversity. J Clin Microbiol. 1988, 26: 2465-2466.

Kumar S, Tamura K, Jakobsen IB, Nei M: MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Bioinformatics. 2001, 17: 1244-1245. 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1244.

Zhang Y, Rajagopalan M, Brown BA, Wallace RJ: Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA PCR for comparison of Mycobacterium abscessus strains from nosocomial outbreaks. J Clin Microbiol. 1997, 35: 3132-3139.

Choi GE, Chulhun LC, Whang J, Kim HJ, Kwon OJ, Koh WJ, Shin SJ: Efficient differentiation of mycobacterium abscessus complex isolates to the species level by a novel PCR-based variable-number tandem-repeat assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2011, 49: 1107-1109. 10.1128/JCM.02318-10.

Zelazny AM, Root JM, Shea YR, Colombo RE, Shamputa IC, Stock F, Conlan S, McNulty S, Brown-Elliott BA, Wallace RJ, Olivier KN, Holland SM, Sampaio EP: Cohort study of molecular identification and typing of Mycobacterium abscessus, Mycobacterium massiliense, and Mycobacterium bolletii. J Clin Microbiol. 2009, 47: 1985-1995. 10.1128/JCM.01688-08.

Acknowledgments

IBK was financially supported by the Oeuvre Antituberculeuse des Bouches du Rhône. MS was financially supported by Infectiopole Sud Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

MS and IBK performed molecular analyses. MD designed the study. IBK, MS and MD interpreted data and wrote the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sassi, M., Ben Kahla, I. & Drancourt, M. Mycobacterium abscessus multispacer sequence typing. BMC Microbiol 13, 3 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-13-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-13-3