Abstract

Background

In Enterococcus faecalis the genes encoding the enzymes involved in citrate metabolism are organized in two divergent operons, citHO and oadHDB-citCDEFX-oadA-citMG (citCL locus). Expression of both operons is specifically activated by adding citrate to the medium. This activation is mediated by binding of the GntR-like transcriptional regulator (CitO) to the cis-acting sequences located in the cit intergenic region. Early studies indicated that citrate and glucose could not be co-metabolized suggesting some form of catabolite repression, however the molecular mechanism remained unknown.

Results

In this study, we observed that the citHO promoter is repressed in the presence of sugars transported by the Phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate Phosphotranserase System (PTS sugars). This result strongly suggested that Carbon Catabolic Repression (CCR) impedes the expression of the activator CitO and the subsequent induction of the cit pathway. In fact, we demonstrate that CCR is acting on both promoters. It is partially relieved in a ccpA-deficient E. faecalis strain indicating that a CcpA-independent mechanism is also involved in regulation of the two operons. Furthermore, sequence analysis of the citH/oadH intergenic region revealed the presence of three putative catabolite responsive elements (cre). We found that they are all active and able to bind the CcpA/P-Ser-HPr complex, which downregulates the expression of the cit operons. Systematic mutation of the CcpA/P-Ser-HPr binding sites revealed that cre1 and cre2 contribute to citHO repression, while cre3 is involved in CCR of citCL

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study establishes that expression of the cit operons in E. faecalis is controlled by CCR via CcpA-dependent and -independent mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are widely used in food industry due to their capacity to convert sugar into lactic acid. However, they can also metabolize other organic compounds present in the raw material utilized for food fermentation. Citrate metabolism has been extensively studied in LAB from the applied point of view, since this fermentation leads to the production of diacetyl. This compound is the most broadly used butter flavor in dairy industry [1, 2] and also contributes to the quality of wine [3].

In LAB, the genes involved in citrate fermentation are usually organized in two operons [4–6]. In these operons, the organization of the genes encoding the holoenzyme of the citrate lyase complex (citD, citE and citF) is extremely well conserved. The clusters also have the accessory genes required for the synthesis and activation of citrate lyase (citC, citG and citX). Two different families of citrate transporters associated to LAB cit operons have been characterized [for review see reference [7]]. The 2HCT (2-hydroxycarboxylate) transporter family includes the citrate/lactate exchanger CitP found in Lactococcus lactis and Weissella paramesenteroides [8], while the proton-coupled citrate-Me2+ symporter of the CitMHS family includes CitH from Enterococcus faecalis [9].

We also contributed to the identification of two different oxaloacetate decarboxylases (OAD) linked to the LAB cit cluster, i) soluble citM [10, 11] and ii) the membrane-bound OAD complex (oadA, oadB, oadD), which in E. faecalis includes also the novel subunit OadH [6].

Finally, two different transcriptional regulators are involved in the activation of the cit operons in LAB: CitI and CitO. CitI belongs to the SorC/DeoR family, and its role in the activation of the cit operons was previously established in W. paramesenteroides [4, 12]. CitI acts in the presence of citrate as an activator, recognizing and binding to two operator sites located in the intergenic region on the cit operons [4, 12]. CitO, a member of the GntR family, was recently described as the activating factor required for the induction of genes encoding the enzymes involved in citrate metabolism in E. faecalis. This activation is mediated by binding of CitO to the cis-acting sequences located in the cit intergenic region (O1 and O2) in the presence of citrate [6].

Citrate fermentation by Enterococcus is relevant, since this group of microorganisms is frequently isolated from the microflora of artisanal cheese [13]. They contribute to cheese ripening and development of their aroma [2]. Early studies [14] showed that E. faecalis could co-metabolize lactose and citrate in milk containing yeast extract but could not co-metabolize glucose and citrate in a complex medium. Rea and Cogan analyzed the factors affecting citrate metabolism and found that it was inhibited by the presence of glucose in several E. faecalis and E. faecium strains [15]. However, the mechanism of glucose-mediated repression of citrate metabolism is poorly understood.

In Firmicutes, the global mechanism of CCR is mediated by the pleiotropically acting transcription factor CcpA [for a review see reference [16, 17]]. The ability of CcpA to bind its target sites, the catabolite responsive elements (cre), is in turn controlled by the presence of its corepressor, serine-phosphorylated HPr (P-Ser-HPr) [18, 19]. HPr has been purified from E. faecalis [20] and the structures of unphosphorylated [21] and serine-phosphorylated HPr [22] have been determined. Like HPr from other Firmicutes, the E. faecalis protein can be phosphorylated at histidine-15 using phosphorylated Enzyme I as phosphate-donor and/or at serine-46 by an ATP-dependent HPr kinase, with the former modification slowing the phosphotransfer to sugar-specific Enzyme IIs [23]. The ATP-dependent HPr kinase gene has been cloned from E. faecalis [24] and expressed in Escherichia coli. The enzyme is bifunctional and acts either as ATP-dependent HPr kinase when bacteria are grown on efficiently used carbon sources or as a P-Ser-HPr dephosphorylating, pyrophosphate-forming phosphorylase when the concentration of ATP and glycolytic intermediates is low. Only P-Ser-HPr, but none of the other HPr forms, is able to form a complex with CcpA active in CCR [19, 25].

The results presented in this manuscript suggest a strong repression of the expression of the cit operons in E. faecalis exerted by CCR. We identified multiple cre sites located in the citH/oadH intergenic region. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that transcriptional repression of the citrate transporter (citH) and the transcription factor (citO) are caused by the presence of two cre sites organized in tandem (cre1 and cre2), whereas control of the catabolic operon oadHDB-citCDEFX-oadA-citMG (citCL locus) requires an independent cre site (cre3). Our studies revealed PTS-mediated CCR mechanisms of the cit operons that are partly CcpA-dependent and partly CcpA-independent.

Results

Catabolite repression of the citoperons occurs in the presence of PTS-sugars

We recently described that the molecular mechanism underlying activation of the cit operons (citHO and citCL) in E. faecalis requires the transcriptional factor CitO [6]. Rea and Cogan had previously suggested that glucose represses citrate metabolism in this bacterium [15]. We therefore studied whether different carbon sources might affect transcription of the genes involved in citrate utilization. To accomplish this task, we measured the activity of the cit promoters (PcitHO and PcitCL, Figure 1A) by fusing them to the promoterless lacZ gene in the vector pTCV-lac [26]. β-Galactosidase activity was determined in cell extracts of E. faecalis JH2-2 harboring plasmid pTCV-PcitHO or pTCV-PcitCL, constructed in a previous work by Blancato et al., 2008 (strains JHB2 and JHB6, Table 1) [6].

Effect of different sugars on expression of the cit operons. A) Genetic organization of E. faecalis cit metabolic operons. PcitHO, promoter of the citHO operon composed of CitH (Me2+-citrate transporter) and CitO (GntR transcriptional regulator); PcitCL promoter of the citCL operon composed of OadHDBA (oxaloacetate decarboxylase membrane complex), CitCDEFXG (citrate lyase and accessory proteins) and CitM (soluble oxaloacetate decarboxylase). O1 and O2 binding sites of the activator CitO. B and C) Influence of diverse PTS and non-PTS sugars on the expression of PcitHO-lacZ and PcitCL-lacZ fusions. JHB2 (JH2-2/pTCV-PcitHO), JHB6 (JH2-2/pTCV-PcitCL), CL1 (CL14/pTCV-PcitHO) and CL2 (CL14/pTCV-PcitCL) were grown in LBC and LBC supplemented with 30 mM initial concentration of different sugars. Levels of accumulated β-galactosidase activity were measured 7 h after inoculation. Error bars represent standard deviation of triplicate measurements.

First, we studied the effect of the presence of PTS or non-PTS sugars on the expression of both transcriptional fusions in the wild type strain. As shown in Figure 1B, when cells were grown in LB medium containing 1% citrate (LBC) expression of both promoters were active. When non-PTS sugars (raffinose, galactose or arabinose) where added to LBC medium, no repression on the cit operons was observed. However, when a PTS sugar was added (glucose, lactose, fructose, maltose, trehalose or cellobiose) to the LBC medium, we found a significant repression of β-galactosidase activity and hence of transcription from both cit promoters (93 to 99% of repression) (Figure 1B), which suggests a general CCR mechanism.

CcpA is controlling citOH and citCLexpression

Because CCR of the cit operons was mainly elicited by PTS sugars, it was likely that it followed the general CCR mechanism of Firmicutes, which is mediated via the DNA-binding protein CcpA, the corepressor P-Ser-HPr and a cis-acting sequence (cre). We first tested the involvement of CcpA in repression of transcription from the PcitHO and PcitCL enterococcal promoters. To this end, the activity of the cit promoters was measured in a CcpA-deficient E. faecalis strain (CL14) [27] containing either the pTCV-PcitHO or the pTCV-PcitCL plasmid (strains CL1 and CL2, respectively) (Figure 1C). β-Galactosidase activity was determined in cell extracts of E. faecalis grown in LBC supplemented with the same PTS and non-PTS sugars, described in Figure 1B. As shown in Figure 1C, no significant repression was observed in the presence of non-PTS sugars and PTS sugars exerted a much weaker repressive effect than in the wild-type strain. However, in these CcpA-defective E. faecalis strains the repression was not completely alleviated. A similar observation was reported for other genes controlled by the CCR in E. faecalis [27].

Subsequently, we tested whether expression of the cit operons depends on the glucose concentration. Hence, we measured the β-galactosidase activity in wild-type and ccpA mutant strains carrying either one of the two transcriptional cit promoter-lacZ fusions. In the wild-type-derived strains (JHB2 and JHB6) β-galactosidase activity decreased when the initial concentration of glucose was raised from 0.25 to 1% (Figure 2A). On the other hand, in the CcpA-deficient strains (CL1 and CL2) activity of the cit promoters was independent of the glucose concentration (Figure 2B). These results suggest that the activity of the cit promoters is tightly regulated by the availability of glucose and that the pleiotropic transcriptional factor CcpA is involved in this process.

Effect of glucose concentrations on the expression of cit operons, CitO levels and citrate lyase activity. A and B) JHB2 (JH2-2/pTCV-PcitHO), JHB6 (JH2-2/pTCV-PcitCL), CL1 (CL14/pTCV-PcitHO) and CL2 strains (CL14/pTCV-PcitCL) were grown in LBC (circle) or LBC supplemented with different initial concentrations of glucose: 0.25% (square), 0.5% (up-pointing triangle) and 1% (down-pointing triangle). The corresponding open symbols indicate the remaining glucose concentration in the culture medium (right axis). Levels of accumulated β-galactosidase activity were measured at different times as indicated in the figure. C and D) E. faecalis strains were grown in the same conditions of panels A and B, and cells extracts were obtained 7 h after inoculation, C) Western blot analysis was performed with polyclonal antibodies raised against CitO. D) Citrate lyase activity was determined as described previously [5]. Error bars represent standard deviation of triplicate measurements.

In order to determine whether these differences in transcriptional repression affect the level of the proteins encoded by the cit operons, the amounts of CitO and citrate lyase activity were determined. First, a Western blot using antibodies raised against purified CitO was performed with extracts of wild type E. faecalis JH2-2 grown during 7 hs in LBC supplemented with different initial concentrations of glucose (0.25%, 0.5% or 1%). A gradual decrease of the intensity of the CitO-specific band accompanied the increase of the glucose concentration (Figure 2C, left panel; lanes 1 to 4). Next, an identical experiment was carried out with the CcpA-deficient strain (CL14) as depicted in Figure 2C (right panel). In this case, CitO levels remained constant despite the increase of the glucose concentration. We also determined PcitCL repression by measuring the citrate lyase activity in cell extracts. Maximal citrate lyase activity was measured in the wild type JH2-2 strain grown in LB supplemented with 1% citrate (Figure 2D, left panel). However, activity diminished when glucose was added to LBC medium, with maximal repression reached at 1% glucose (90% of repression). Citrate lyase activity was also measured in the CcpA-deficient strain CL14 grown under conditions identical to those used for JH2-2. Only 40% repression was observed in this case, with no significant difference between the activities measured at the different glucose concentrations.

Both citoperons are under the direct control of CCR

The divergent organization of the cit genes raises the possibility that the CCR observed could be accomplished by repressing the positive regulator of the pathway (CitO) and the citrate uptake (mediated by CitH). To address this question, CitO was expressed in trans autonomously of the PcitHO promoter (strain JHB11) [6]. In that strain we used the pBM02-derived [28] plasmid, pCitO, in which the expression of citO is under the control of the lactococcal Pcit promoter. As described by Marelli et al., 2010 [28], in E. faecalis expression of different genes put under control of the Pcit promoter was constitutive. In the JHB11-derived strains JHB15 and JHB16 (carrying plasmids pTCV-PcitHO and pTCV-PcitCL, respectively) the activity of the promoters was determined. From Figure 3A it can be seen that in the JHB15 strain repression occurred over the complete range of glucose concentrations tested, whereas in the JHB16 strain (Figure 3B) repression was only noticeable at higher initial glucose concentrations (0.5% (up-pointing triangle) and 1% (down-pointing triangle)). Western blot analysis indicated that CitO levels remained constant in strain JHB11 independently of whether it was grown in presence of citrate (1%) or citrate (1%) and glucose (1%) (Figure 3C). The results presented in Figure 3 suggest that repression of PcitCL is directly mediated by CcpA and that repression of PcitHO is stronger than repression of PcitCL since PcitHO but not PcitCL was repressed at 0.25% initial glucose.

Effect of different glucose concentrations on the expression of cit promoters in a CitO constitutive genetic background. A and B) JHB15 (JHB11/pTCV-PcitHO) and JHB16 strains (JHB11/pTCV-PcitCL) were grown in LBC (circle) or LBC supplemented with different initial concentrations of glucose: 0.25% (square), 0.5% (up-pointing triangle) and 1% (down-pointing triangle). The corresponding open symbols indicate the remaining glucose concentration in the culture medium (right axis). The levels of accumulated β-galactosidase activity were measured at the time points indicated in the figure. Error bars represent the standard deviation of triplicate measurements. C) Western blot analysis was performed in the complemented CitO deficient strain (JHB11), that was cultivated for 6 h in LB medium supplemented with citrate 1% (LBC) or citrate 1% plus glucose 1% (LBCG).

Multiple cre sites mediate the CCR of the citoperons

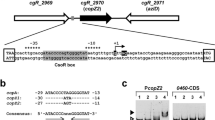

The results presented up to this point show that PTS sugars repress the citrate fermentation pathway through the action of CcpA. A bioinformatic search in the divergent promoter region revealed the presence of three putative catabolite responsive elements (cre sites) highly homologous to the E. faecalis consensus cre site [TG(T/A)NANCGNTN(T/A)CA] [27] and [(T/A)TG(T/A)AA(A/G)CG(C/T)(T/A)(T/A) (T/A)C(T/A)] [29]. cre1 (C1) and cre2 (C2) are located downstream from PcitHO; C1 is located in the coding region of citH and C2 in the untranslated region at 207-bp and 94-bp, respectively, downstream from the transcriptional start site (TSS) of the citHO operon (distances are indicated relative to the center of symmetry). cre3 (C3) is located 97-bp downstream from the citCL TSS within the coding region of oadH (Figure 4).

Binding of CcpA to DNA fragments containing different cre sites. A) Nucleotide sequence of the citH-oadH intergenic regions. Locations of transcription start sites are indicated (+1); -10 and -35; regions are shown underlined. Arrows indicate direction of transcription and translation. CitO binding sequences are displayed in dotted boxes and putative cre sites in grey boxes. B, C and D) Images of gel shift assays performed with different amplicons (A, B and C respectively) covering each cre site or mutated cre site amplicons (Bm and Cm), increasing concentrations of CcpA and fixed concentrations of HPr or P-Ser-HPr.

To address the question whether these putative cre sites were recognized by E. faecalis CcpA, a His6-CcpA fusion protein was overproduced in E. coli. The purified fusion protein was used in gel mobility shift assays using DNA fragments corresponding to the individual cre sites. The cre amplicons were exposed to increasing concentrations of purified CcpA and a fixed concentration of HPr or P-Ser-HPr. FBP was also included in the reaction buffer since its addition enhanced CcpA binding to cre sites (not shown). As shown in Figure 4, CcpA without its corepressor did not bind to the cre sites under the conditions employed; including HPr in the assay solution did not lead to detectable CcpA-DNA interaction. However, the combination of CcpA with its corepressor P-Ser-HPr resulted in the formation of one retarded complex for each amplicon (Figure 4B, lanes 8 and 9; C, lanes 12-15 and D, lanes 8 and 9). The binding specificity was confirmed by determining that CcpA did not bind to mutated amplicons (Bm and Cm), in which the cre site was changed to TaTAcGatTgAAtc (lowercase letters indicate mismatches with the consensus sequence) (Figure 4C, lanes 16 and 17; D, Lanes 10 and 11). A comparison of the binding pattern suggests that the P-Ser-HPr-CcpA complex possesses a 10-fold higher affinity for cre site C2 than for C1 or C3, since with 0.05 μM CcpA it is possible to observe the formation of a retarded complex (Figure 4C, lane 12) whereas binding to C1 or C3 required a concentration of 0.5 μM CcpA (lane 8 in Figure 4B and 4D, respectively).

In order to test the role of these sites in the transcription regulation mechanism mediated by CcpA, a set of DNA fragments corresponding to altered cit promoter regions (i.e. cre sites deleted or mutated) were fused to the promoterless lacZ reporter gene of the pTCV-lac vector (Figure 5). Plasmids harboring the Pcit-lacZ transcriptional fusions were electroporated into the E. faecalis JHB11 strain.

Schematic representation of the pTCV- lac derived plasmids. Promoter regions of the citHO and citCL operons are shown. The different cre sites are indicated by boxes (C1, C2, C3 and M for mutated cre sites). The glucose repression index represents the ratio of accumulated β-galactosidase activity between cell extracts from cultures grown in LBC and LBCG medium (MULBC/MULBGC) for 7 hours.

We used this strain, in which citO is under the control of the constitutive L. lactis promoter Pcit, in order to determine the specific repression mediated by CcpA interacting with the cre sites. Accumulated β-galactosidase activity was measured in the JHB11-derived strains grown in the presence of only citrate or of both the inducer citrate and the repressor glucose. In Figure 5, β-galactosidase activities determined 7 hs after inoculation are expressed as glucose repression index (ri = MULBC/MULBCG, where MULBC and MULBCG represent the β-galactosidase activities measured in cells grown in the absence or presence of glucose, respectively). We first studied the effect of alterations in the multiple cre sites on expression from the citHO promoter. A comparison of the glucose repression index for the transcriptional fusion in strain JHS1, where cre sites 1 and 2 are present, with that determined for strain JHS2 containing only functional C1, revealed no significant difference (ri: 20.0 ± 1.0 vs 17.2 ± 2.0) (Figure 5). When C1 was deleted from the citHO promoter region we found that C2 was still capable of causing CCR on the citHO promoter, but with a slightly lower repression index (ri: 11.5 ± 0.2) (Figure 5, strain JHS3). In contrast, when the C2 site was mutated (strain JHS4) the glucose repression index dropped more than 4-fold compared with strain JHS3 (ri: 2.6 ± 0.6).

We subsequently studied whether the role of C3 in the repression of PcitCL. The glucose repression index (ri: 11.1 ± 1.0) measured for strain JHS6 indicates that it is submitted to CCR. This repression was diminished in strain JHS7 lacking C3 in the PcitCL promoter region (Figure 5).

We also found that C3 was not involved in PcitHO repression, since the presence or absence of C3 had no effect on the repression of this promoter (strains JHS4 and JHS5). Moreover, C2 had no influence on PcitCL repression because deletion of C2 did not produce a significant difference in the glucose repression index of strains JHS7 (C2 present) and JHS8 (C2 deleted) (Figure 5).

Altogether, these results indicate that cre1 and cre2 are responsible for CCR of the citHO operon, and cre3 is the cis-acting sequence responsible of the repression of the citCL operon.

Discussion

In this work we demonstrate that citrate metabolism in E. faecalis is under the control of the general carbon catabolic repression mechanism and elucidate the details of the CcpA/P-Ser-HPr-dependent molecular mechanism. Clearly, our results establish that CcpA-dependent and -independent mechanisms are involved in CCR of the cit operons depending on the repressing sugar employed.

We found that the global transcriptional factor CcpA exerts transcriptional regulation via the three active cre sites which allows controlling the expression of the citHO operon as well as the catabolic operon citCL. Band shift assays showed that the P-Ser-HPr-CcpA complex has a higher affinity for cre site C2 than for C1 or C3. Miwa et al. analyzed several cre sites from B. subtilis and concluded that strong similarity of cre sequences to the consensus sequence favors a physiological role and that a more extended palindrome of cre sequences correlates with stronger repression [30]. Remarkably, Schumacher et al. recently established that P-Ser-HPr-CcpA complex binds to different cres with similar affinities. However, it is important to note that this analysis was performed with P-Ser-HPr-CcpA interacting only with cre sites belonging to different operators [31]. The difference in affinity that we observed between C1, and C2 or C3 might therefore be related to the surrounding sequences of the cre region [32]. This also might explain why C2, although having the highest affinity for CcpA, seems not to be the dominant cre in repression.

Interestingly, analysis of the effect of different PTS sugars on the cit operons showed significant differences. The presence of lactose in the growth medium produced a strong repressive effect which was completely relieved in the CcpA deficient strain. However, with other PTS sugars, such as glucose, this repressive effect was only partially relieved in the CcpA-defective strain. This result suggests that lactose repression of the cit operons is exclusively mediated via CcpA, whereas for the other sugars CcpA-independent mechanisms seem to exist. This observation prompted us to look for alternative PTS repression mechanisms involved in CCR observed in the cit operons. First, we searched for phosphorylatable domains in the transcriptional regulator CitO that could regulate its activator function in response to their phosphorylation state [33]. A domain search analysis of the amino acid sequence by means of InterProScan Sequence Search [34] revealed that CitO does not possess neither PRDs nor EIIA or HPr domains. We also dismissed inducer exclusion as possible mechanism of CcpA-independent repression because the E. faecalis strain grown in LB in the presence of citrate and glucose maintained the ability to incorporate [14C]-citrate (data not shown). Interestingly, Zeng et al. suggested that there is a direct involvement of P-Ser-HPr and the glucose/mannose-PTS EIIABMan (ManL) in CCR of the fructan hydrolase (fruAB) and the levDEFGX operons [35]. Furthermore, Opsata et al. showed that in an E. faecalis V583 mutant strain with strong reduction in expression of the mannose PTS operon, the citE gene was upregulated 5-fold when compared with the wild type grown in BHI medium (which contains glucose and citrate, among other components) [29]. We constructed a JH2-2-derived mannose PTS deficient strain and a ccpA PTSMan double mutant. Unfortunately, we could not find an apparent correlation between the activity of the promoters in the presence of citrate (LBC) and glucose plus citrate. Finally, homologs to CcpN (EF1025) and YqfL (EF2419) were found in the E. faecalis genome. These regulators are involved in CcpA-independent CCR in B. subtilis [36] and their direct or indirect participation in the regulation of the cit operons cannot be ruled out. Recent publications using transcriptome analysis suggested that the cit operons might be regulated by Rex (a regulator responding to NAD/NADH ratio) [37] and indirectly by Ers (a PrfA-like regulator) [38]. Nevertheless, their contribution to the regulation in the presence of citrate and PTS sugars remains to be determined. Although convincing evidence for a CcpA-independent mechanism of repression is presented in this work, more experiments will be necessary to elucidate it at the molecular level.

One question which arose from our studies was why does E. faecalis regulate citrate transport and metabolism in such a strict way? In Bacillus subtilis, citrate uptake interferes directly with the regulation of the Krebs cycle enzymes, which explains why expression of the transporter is tightly controlled [39]. However, citrate transport by enterococcal cells will not cause an imbalance of metabolites of the TCA because E. faecalis lacks most of the enzymes of the Krebs cycle. Nevertheless, like B. subtilis, E. faecalis transports citrate complexed with a well-defined set of bivalent metal ions: Ca2+, Sr2+, Mn2+, Cd2+, and Pb2+ [9]. The ability to take up toxic bivalent metal ions in complex with citrate might render E. faecalis sensitive to the toxic heavy metal ions in citrate-containing medium. It is possible that the sophisticated regulation of cit gene expression allows E. faecalis to resist and persist in different environments and to synthesize in controlled form the enzymes necessary for the transport and metabolism of the nutrients in order to optimize its growth.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study shows that citrate metabolism in E. faecalis is controlled by general Carbon Catabolic Repression. We found that CcpA exerts the transcriptional regulation through three active cre sites which allows control of the expression of the citHO operon as well as the catabolic operon citCL. Thus, this complex regulatory mechanism ensures the control not only of the transcriptional factor citO but also of the citrate transporter citH, which reduces the uptake of the inducer required by the activator. An extra control point was found in the citCL operon which fine-tunes the levels of degradative enzymes encoded by this operon. Also, we found that an independent mechanism of CCR is operative on the citrate operons in this bacterium. All these results contribute to understand how E. faecalis controls the hierarchical use of the carbon source that allows it to survive in different habitats and growth conditions.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Cultures of E. faecalis were grown at 37°C without shaking in 100 ml sealed bottles containing 20-50 ml of Luria-Bertani medium (LB) [40], supplemented with 1% trisodium citrate (LBC) or different carbon sources as indicated with an initial pH of 7.0. The growth medium was supplemented with kanamycin (1000 μg/ml) for strains carrying pTCV-derived plasmids; erythromycin (5 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (10 μg/ml) for JHB11-derived strains, or erythromycin (150 μg/ml) for the CL14 strain (Table 1).

E. coli strain DH5α was used as an intermediate host for cloning and E. coli BL21 (DE3) was used for overproduction of His6-CcpA. E. coli strains were routinely grown aerobically at 37°C in LB and transformed as previously described [40]. Growth was monitored by measuring absorbance at 600 nm in a Beckman DU640 spectrophotometer. Aerobic growth was achieved by gyratory shaking at 250 rpm. Ampicilin (100 μg/ml), erythromycin (150 μg/ml) or kanamycin (50 μg/ml) was included in the medium to select cells harboring ampicillin-, erythromycin- or kanamycin-resistant plasmids. 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (20 μg/ml) (X-GAL) was used to identify recombinant plasmids with DNA insertions that impaired β-galactosidase activity in strain DH5α induced with 0.5 mM IPTG.

Construction of plasmids with Pcit-lacZtranscriptional fusions and β-galactosidase assays

The plasmids bearing the promoter-lacZ transcriptional fusions, listed in Table 2, are all derivatives of the pTCV-lac vector [26], and the oligonucleotides used in their construction are also indicated in Table 2. In order to mutate the cre2 site, the oligonucleotides EfHpromU-Cre2mut_Lo and Cre2mut_Up-EfDpromL (Table 3) were used for the amplification of two overlap extension PCR. These PCR products were used as a DNA template for another PCR using the oligonucleotides EfHpromU and EfDpromL, the amplification products were cloned into the PCR-Blunt II-TOPO vector. The cre3 site was mutated by following the same protocol but using the oligonucleotides EfHpromU-Cre3mut_Lo and Cre3mut_Up-EfDpromL (Table 3). Deletion of cre1 was carried out by PCR using primers EfbscitN and Efint_Lo. The pTOPO-derived plasmids were digested with EcoRI and each released fragment was ligated into the corresponding site of the pTCV-lac vector. The desired orientation of the fragments was determined by PCR. Cloned fragments were checked by sequencing at the DNA sequencing Facility of the University of Maine, USA.

Cells were grown overnight in LBC broth and different carbon sources were added to the growth medium at the specified concentrations as indicated in the figures or in the text. Overnight cultures were diluted to an O.D.660 = 0.08 and grown in LB supplemented with a carbon source until the cells reached early stationary phase. β-Galactosidase activity was measured as described by Israelsen et al. [41].

Protein purification and HPr phosphorylation

The gene encoding the transcriptional regulator CcpA was amplified by PCR using genomic DNA from E. faecalis JH2-2 as the template, following a standard protocol. The forward primer Ef-ccpAU introduced a NdeI site around the initiation codon of the ccpA gene, and the backward primer Ef-ccpAL introduced a BamHI site downstream of the stop codon (Table 2 and Table 3). The PCR product was double-digested and ligated into the corresponding restriction sites of vector pET-28a(+) (Novagen). The resulting plasmid, named pET-CcpA, codes for CcpA extended with a 6-histidine tag at the N terminus (Table 2). The correct sequence of the insert was confirmed, and the plasmid was subsequently introduced into E. coli BL21 (DE3) for ccpA overexpression.

E. coli BL21 (DE3) harboring the pET-ccpA plasmid was grown in LB at 37°C until an O.D.600= 0.6 was reached. Next, CcpA expression was induced by addition of 0.5 mM IPTG. Following an overnight culture, cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in ice-cold Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 8.0), containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 300 mM NaCl and 5% glycerol. Cells were disrupted by passing them through a French Pressure cell. The suspension was centrifuged and the supernatant was mixed with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (Novagen). His6-CcpA was eluted with imidazole and the purified protein was dialyzed against binding buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.6, 150 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol) and stored at -80 °C for further studies.

Lactobacillus casei HprK/P(V267F) and Enterococcus casseliflavus HPr were overproduced using pQE30 vector and purified following a standard protocol, as described previously [42].

Seryl-phosphorylated E. casseliflavus HPr was prepared as described by Mazé et al. [43] using L. casei V267F mutant HprK/P, which possesses kinase activity but has almost completely lost the phosphorylase function [42]. About 0.5 mg of HPr was incubated for 30 min at 37°C in 1 ml final volume containing also 10 μg of HprK/P(V267F), 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP), and 5 mM ATP. To inactivate HprK/P(V267F), the samples were heated for 5 min at 75°C before they were desalted on PD-10 columns (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) to remove ATP and FBP and lyophilized. HPr and P-Ser-HPr were separated by electrophoresis on nondenaturing 12.5% polyacrylamide gels and visualized by staining with Coomassie blue; usually 99% of the HPr was converted into P-Ser-HPr.

DNA labeling

The synthetic oligonucleotides EfHpromU, Efint4_Lo, EfbsPoadA were labeled at their 5' ends using [γ-32P]ATP (NEN PerkinElmer). The labeled oligonucleotides were purified using a Zeba Desalt Spin Column (Thermo scientific). DNA fragments containing different cre sites were amplified by PCR; for the amplicons A, B and C we used the primer pairs EfHpromU-EfcitNUp, EfbscitN-Efint4_Lo and EfbsPoadA-Efbsint_Up, respectively. Amplicon Bm was amplified with the primers EfbscitN-Efint4_Lo using pTCV-PcitHO-C1C2M as template and amplicon Cm with the primers EfbsPoadA-Efbsint_Up using pTCV-PcitCL-C2C3M as template. The amplicons were purified from a 2% agarose gel prior to their use for binding reactions.

Gel mobility shift assays

Gel mobility assays were performed as follows. CcpA was incubated with 5 μM HPr or P-Ser-HPr in the reaction mix containing 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM KCl, 20 mM FBP, 0.05 mg/ml herring DNA and 5% glycerol for 15 min at 37°C subsequently DNA was added to the mixture reaching a final concentration of 0.1 nM. After incubation for another 15 min at 37°C, samples were loaded on a 5% polyacrylamide gel. Gels were dried onto Whatman 3MM paper and exposed to a storage phosphor screen, and band patterns were detected in a GE Healthcare Life Sciences 840 Phosphorimager.

Citrate lyase activity

To determine citrate lyase activity, cultures of E. faecalis JH2-2 and CL14 were grown for 7 hours in LB supplemented with 1% citrate and different glucose concentrations (0.25, 0.5 and 1%). Cells were harvested and resuspended in 200 μl of 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) supplemented with 3 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Total protein extracts were prepared by treating the cells with 20 U/μl mutanolysin (Sigma) for 20 min at 37°C. Cells were then vortexed with glass beads (425-600 microns, Sigma) and cell debris was removed by centrifugation. The assay mixture contained 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), 5 mM trisodium citrate, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM NADH, 25 U of malate dehydrogenase (Sigma), and 20 or 40 μg of total protein from different cell extracts in a final volume of 1 ml. Chemical acetylation of citrate lyase was performed by incubating protein extracts for 5 min at 25°C with 5 mM acetic anhydride and then used immediately for determination of citrate lyase activity. NADH oxidation was measured in a spectrophotometer at 340 nm. One unit of enzyme activity is defined as 1 pmol of citrate converted to acetate and oxaloacetate per min under the conditions used [5].

Western blot analysis

E. faecalis strains JH2-2, JHB11 and CL14 were grown individually at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with 1% citrate and different glucose concentrations (0.25, 0.5 and 1%). Cells were harvested by centrifugation and crude extracts were prepared by vortexing cells with glass beads (425-600 microns, Sigma). Proteins from cell extracts were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on a 12% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by electroblotting.

Proteins were detected with rabbit polyclonal antisera raised against CitO of E. faecalis. Antibodies were visualized by using goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G-AP secondary antibodies (Bio-Rad).

Analytical methods

Glucose concentrations were determined enzymatically with a glucose oxidase-peroxidase based system following the protocol provided by the supplier (Wiener Labs test kit).

References

Hugenholtz J: Citrate metabolism in lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993, 12: 165-178. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1993.tb00017.x.

Giraffa G: Enterococci from foods. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2002, 26 (2): 163-171. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00608.x.

Mills D, Rawsthorne H, Parker C, Tamir D, Makarova K: Genomic analysis of Oenococcus oeni PSU-1 and its relevance to winemaking. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005, 29 (3): 465-475.

Martin MG, Magni C, de Mendoza D, Lopez P: CitI, a Transcription Factor Involved in Regulation of Citrate Metabolism in Lactic Acid Bacteria. J Bacteriol. 2005, 187 (15): 5146-5155. 10.1128/JB.187.15.5146-5155.2005.

Martin MG, Sender PD, Peiru S, de Mendoza D, Magni C: Acid-Inducible Transcription of the Operon Encoding the Citrate Lyase Complex of Lactococcus lactis Biovar diacetylactis CRL264. J Bacteriol. 2004, 186 (17): 5649-5660. 10.1128/JB.186.17.5649-5660.2004.

Blancato VS, Repizo GD, Suarez CA, Magni C: Transcriptional Regulation of the Citrate Gene Cluster of Enterococcus faecalis Involves the GntR Family Transcriptional Activator CitO. J Bacteriol. 2008, 190 (22): 7419-7430. 10.1128/JB.01704-07.

Sobczak I, Lolkema JS: The 2-Hydroxycarboxylate Transporter Family: Physiology, Structure, and Mechanism. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005, 69 (4): 665-695. 10.1128/MMBR.69.4.665-695.2005.

Martin M, Corrales M, de Mendoza D, Lopez P, Magni C: Cloning and molecular characterization of the citrate utilization citMCDEFGRP cluster of Leuconostoc paramesenteroides. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999, 174 (2): 231-238.

Blancato V, Magni C, Lolkema J: Functional characterization and Me ion specificity of a Ca-citrate transporter from Enterococcus faecalis. FEBS J. 2006, 273 (22): 5121-5130. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05509.x.

Espariz M, Repizo G, Blancato V, Mortera P, Alarcon S, Magni C: Identification of Malic and Soluble Oxaloacetate Decarboxylase Enzymes in Enterococcus faecalis. FEBS J. 2011

Sender P, Martin M, Peiru S, Magni C: Characterization of an oxaloacetate decarboxylase that belongs to the malic enzyme family. FEBS Lett. 2004, 570 (1-3): 217-222. 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.06.038.

Martin M, Magni C, Lopez P, de Mendoza D: Transcriptional Control of the Citrate-Inducible citMCDEFGRP Operon, Encoding Genes Involved in Citrate Fermentation in Leuconostoc paramesenteroides. J Bacteriol. 2000, 182 (14): 3904-3912. 10.1128/JB.182.14.3904-3912.2000.

Foulquie Moreno M, Sarantinopoulos P, Tsakalidou E, De Vuyst L: The role and application of enterococci in food and health. Int J Food Microbiol. 2006, 106 (1): 1-24. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.06.026.

Sarantinopoulos P, Kalantzopoulos G, Tsakalidou E: Citrate Metabolism by Enterococcus faecalis FAIR-E 229. Appl Envir Microbiol. 2001, 67 (12): 5482-5487. 10.1128/AEM.67.12.5482-5487.2001.

Rea M, Cogan T: Glucose prevents citrate metabolism by enterococci. Int J Food Microbiol. 2003, 88 (2-3): 201-206. 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00181-8.

Deutscher J: The mechanisms of carbon catabolite repression in bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008, 11 (2): 87-93. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.007.

Fujita Y: Carbon catabolite control of the metabolic network in Bacillus subtilis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2009, 73 (2): 245-259. 10.1271/bbb.80479.

Galinier A, Deutscher J, Martin-Verstraete I: Phosphorylation of either crh or HPr mediates binding of CcpA to the bacillus subtilis xyn cre and catabolite repression of the xyn operon. J Mol Biol. 1999, 286 (2): 307-314. 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2492.

Schumacher M, Allen G, Diel M, Seidel G, Hillen W, Brennan R: Structural basis for allosteric control of the transcription regulator CcpA by the phosphoprotein HPr-Ser46-P. Cell. 2004, 118 (6): 731-741. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.027.

Deutscher J, Pevec B, Beyreuther K, Kiltz H, Hengstenberg W: Streptococcal phosphoenolpyruvate-sugar phosphotransferase system: amino acid sequence and site of ATP-dependent phosphorylation of HPr. Biochemistry. 1986, 25 (21): 6543-6551. 10.1021/bi00369a031.

Jia Z, Vandonselaar M, Quail J, Delbaere L: Active-centre torsion-angle strain revealed in 1.6 A-resolution structure of histidine-containing phosphocarrier protein. Nature. 1993, 361 (6407): 94-97. 10.1038/361094a0.

Audette G, Engelmann R, Hengstenberg W, Deutscher J, Hayakawa K, Quail J, Delbaere L: The 1.9 A resolution structure of phospho-serine 46 HPr from Enterococcus faecalis. J Mol Biol. 2000, 303 (4): 545-553. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4166.

Hengstenberg W, Kohlbrecher D, Witt E, Kruse R, Christiansen I, Peters D, Pogge von Strandm R, Stadtler P, Koch B, Kalbitzer H: Structure and function of proteins of the phosphotransferase system and of 6-phospho-beta-glycosidases in gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993, 12 (1-3): 149-163.

Kravanja M, Engelmann R, Dossonnet V, Bluggel M, Meyer H, Frank R, Galinier A, Deutscher J, Schnell N, Hengstenberg W: The hprK gene of Enterococcus faecalis encodes a novel bifunctional enzyme: the HPr kinase/phosphatase. Mol Microbiol. 1999, 31 (1): 59-66. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01146.x.

Reizer J, Bergstedt U, Galinier A, Kuster E, Saier M, Hillen W, Steinmetz M, Deutscher J: Catabolite repression resistance of gnt operon expression in Bacillus subtilis conferred by mutation of His-15, the site of phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphorylation of the phosphocarrier protein HPr. J Bacteriol. 1996, 178 (18): 5480-5486.

Poyart C, Trieu-Cuot P: A broad-host-range mobilizable shuttle vector for the construction of transcriptional fusions to beta-galactosidase in gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997, 156 (2): 193-198. 10.1016/S0378-1097(97)00423-0.

Leboeuf C, Leblanc L, Auffray Y, Hartke A: Characterization of the ccpA Gene of Enterococcus faecalis: Identification of Starvation-Inducible Proteins Regulated by CcpA. J Bacteriol. 2000, 182 (20): 5799-5806. 10.1128/JB.182.20.5799-5806.2000.

Marelli B, Magni C: A simple expression system for Lactococcus lactis and Enterococcus faecalis. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010, 26 (6): 999-1007. 10.1007/s11274-009-0262-5.

Opsata M, Nes I, Holo H: Class IIa bacteriocin resistance in Enterococcus faecalis V583: the mannose PTS operon mediates global transcriptional responses. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10: 224-10.1186/1471-2180-10-224.

Miwa Y, Nakata A, Ogiwara A, Yamamoto M, Fujita Y: Evaluation and characterization of catabolite-responsive elements (cre) of Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28 (5): 1206-1210. 10.1093/nar/28.5.1206.

Schumacher MA, Sprehe M, Bartholomae M, Hillen W, Brennan RG: Structures of carbon catabolite protein A-(HPr-Ser46-P) bound to diverse catabolite response element sites reveal the basis for high-affinity binding to degenerate DNA operators. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39 (7): 2931-2942. 10.1093/nar/gkq1177.

Kim JH, Chambliss GH: Contacts between Bacillus subtilis catabolite regulatory protein CcpA and amyO target site. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25 (17): 3490-3496. 10.1093/nar/25.17.3490.

Deutscher J, Francke C, Postma PW: How phosphotransferase system-related protein phosphorylation regulates carbohydrate metabolism in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006, 70 (4): 939-1031. 10.1128/MMBR.00024-06.

Zdobnov EM, Apweiler R: InterProScan - an integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. Bioinformatics. 2001, 17 (9): 847-848. 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.847.

Zeng L, Burne R: Seryl-phosphorylated HPr regulates CcpA-independent carbon catabolite repression in conjunction with PTS permeases in Streptococcus mutans. Mol Microbiol. 2010, 75 (5): 1145-1158. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.07029.x.

Stulke J, Arnaud M, Rapoport G, Martin-Verstraete I: PRD--a protein domain involved in PTS-dependent induction and carbon catabolite repression of catabolic operons in bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1998, 28 (5): 865-874. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00839.x.

Mehmeti I, Jonsson M, Fergestad EM, Mathiesen G, Nes IF, Holo H: Transcriptome, Proteome, and Metabolite Analyses of a Lactate Dehydrogenase-Negative Mutant of Enterococcus faecalis V583. Appl Envir Microbiol. 2011, 77 (7): 2406-2413. 10.1128/AEM.02485-10.

Riboulet-Bisson E, Sanguinetti M, Budin-Verneuil A, Auffray Y, Hartke A, Giard JC: Characterization of the Ers Regulon of Enterococcus faecalis. Infect Immun. 2008, 76 (7): 3064-3074. 10.1128/IAI.00161-08.

Repizo G, Blancato V, Sender P, Lolkema J, Magni C: Catabolite repression of the citST two-component system in Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006, 260 (2): 224-231. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00318.x.

Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T, (eds.): Molecular Cloning: a laboratory manual. 1989, New York

Israelsen H, Madsen S, Vrang A, Hansen E, Johansen E: Cloning and partial characterization of regulated promoters from Lactococcus lactis Tn917-lacZ integrants with the new promoter probe vector, pAK80. Appl Envir Microbiol. 1995, 61 (7): 2540-2547.

Monedero V, Poncet S, Mijakovic I, Fieulaine S, Dossonnet V, Martin-Verstraete I, Nessler S, Deutscher J: Mutations lowering the phosphatase activity of HPr kinase/phosphatase switch off carbon metabolism. EMBO J. 2001, 20 (15): 3928-3937. 10.1093/emboj/20.15.3928.

Maze A, Boel G, Poncet S, Mijakovic I, Le Breton Y, Benachour A, Monedero V, Deutscher J, Hartke A: The Lactobacillus casei ptsHI47T Mutation Causes Overexpression of a LevR-Regulated but RpoN-Independent Operon Encoding a Mannose Class Phosphotransferase System. J Bacteriol. 2004, 186 (14): 4543-4555. 10.1128/JB.186.14.4543-4555.2004.

Clewell DB, Tomich PK, Gawron-Burke MC, Franke AE, Yagi Y, An FY: Mapping of Streptococcus faecalis plasmids pAD1 and pAD2 and studies relating to transposition of Tn917. J Bacteriol. 1982, 152 (3): 1220-1230.

Jacob AE, Hobbs SJ: Conjugal Transfer of Plasmid-Borne Multiple Antibiotic Resistance in Streptococcus faecalis var. zymogenes. J Bacteriol. 1974, 117 (2): 360-372.

Maguin E, Prevost H, Ehrlich S, Gruss A: Efficient insertional mutagenesis in lactococci and other gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1996, 178 (3): 931-935.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (PICT 2010-1828 and PICT 2008-1562; Argentina) a European Union grant (BIAMFood, contract KBBE- 211441) and MinCyt-ECOS collaboration program project number A09B03. C. S. is a fellow of CONICET (Argentina), and V. B. and C. M. are Career Investigators from CONICET (Argentina).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

CAS carried out the molecular genetic studies, participated in the β-galactosidase activities and protein purification. VSB carried out the molecular genetic studies, participated in the band shift assay and helped to draft the manuscript. SP participated in the purification of the proteins and Band shift assay. JD participated in the coordination and helped to draft the manuscript and CM participated in experiment design, coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Cristian A Suárez, Víctor S Blancato contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Suárez, C.A., Blancato, V.S., Poncet, S. et al. CcpA represses the expression of the divergent cit operons of Enterococcus faecalis through multiple cresites. BMC Microbiol 11, 227 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-11-227

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-11-227