Abstract

Background

Enterococci are increasingly associated with opportunistic infections in Humans but the role of the oral cavity as a reservoir for this species is unclear. This study aimed to explore the carriage rate of Enterococci in the oral cavity of Tunisian children and their antimicrobial susceptibility to a broad range of antibiotics together with their adherence ability to abiotic and biotic surfaces.

Results

In this study, 17 E. faecalis (27.5%) and 4 E. faecium (6.5%) were detected. The identified strains showed resistance to commonly used antibiotics. Among the 17 isolated E. faecalis, 12 strains (71%) were slime producers and 5 strains were non-producers. Among the 4 E. faecium, 2 strains were slime producers. All the tested strains were able to adhere to at least one of the two tested cell lines. Our result showed that 11 E. faecalis and 2 E. faecium strains adhered strongly to Hep-2 as well as to A549 cells.

Conclusions

Drugs resistance and strong biofilm production abilities together with a high phenotypic adhesion to host cells are important equipment in E. faecalis and E. faecium which lead to their oral cavity colonization and focal infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Enterococci are normal commensals Gram-positive cocci that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract and the human oral cavity [1]. The increasing interest to Enterococci in clinical microbiology is linked to their high level intrinsic resistance to currently available antibiotics [2]. Enterococcus faecalis is responsible for up to 90% of human enterococcal infections [3]. However, Enterococcus faecium accounts for the remainder of infections caused by Enterococci spp. [1]. Data on oral prevalence of E. faecalis vary widely in different studies [4] which ranged from 0 to 50% depending on the oral source of the tested specimens (saliva, root canals, plaque) and the studied populations [5]. Sedgley et al., [4] reported the presence of E. faecalis in 29% of oral rinse samples and 22% in gingival sulcus samples collected from 41 endodontic subjects. Recently, drugs resistance in E. faecalis and E. faecium and their possible contribution to horizontal gene transfer underline the growing attention being paid to Enterococci in the oral cavity [6].

To date, E. faecalis, are not considered to be part of the normal oral microbiota [7]. However it has been considered as the most common species recovered from teeth with failed endodontic treatment [8] and to be the predominant infectious agent associated with secondary endodontic infections [9]. E. faecalis was shown to reside within different layers of the oral biofilm leading to failure of endodontic therapy [10]. These biofilms may contain up to several hundred bacterial species [11]. Enterococci in biofilms are more highly resistant to antibiotics than planktonically growing strains [12]. The possible role of adhesion and cells invasion as virulence factor associated with enterococcal infections has been reported [13]. Their capacity to bind to various medical devices has been associated with their ability to produce biofilms [14].

The attachment of different E. faecalis strains to several extracellular matrix proteins has been reported [15]. Bacterial adherence to host cells such as human urinary tract epithelial cells [16] and Girardi heart cells [17] was recognized as the initial event in the pathogenesis of many infections.

In view of the limited data, this study aimed to describe the Enterococci prevalence in the oral cavity of Tunisian children (caries active and caries free), their antimicrobial susceptibility to a broad range of antibiotics together with their adherence ability to abiotic and biotic surfaces.

Methods

Patients and Bacterial strains

The study was done on 62 children (34 caries active and 28 caries free) from the Dentistry Clinic of Monastir, Tunisia. The age group selected for the present investigation was about 4 to 12 years. Ethical clearance was taken prior to the commencement of study. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all participants. All clinical procedures were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Monastir University, Tunisia. A detailed medical and dental history was obtained from each parent. The criteria for inclusion were: no antibiotic treatment during the 4 weeks previous to sampling, no use of mouth rinses or any other preventive measure that might involve exposure to antimicrobial agents and no systemic disease.

Samples were taken from the oral cavity of each patient with a sterile swab. After incubation in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium during 2 h, the swab was plated on Bile Esculin Agar plates. Suspected colonies of Enterococci were tested for their positive Gram stain and catalase reaction (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK).

Species identification was confirmed using API 20 Strep strips (Bio-Merieux, France) according to the manufacturer's recommendation and the results were read using an automated microbiological mini-API (Bio-Merieux, France).

Molecular detection of oral Enterococci

Genomic DNA was extracted using a Wizard Genomic Purification Kit (Promega, Lyon, France). The presence of oral Enterococci was detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using specific primers targeted for E. faecalis; E1, 5'-ATC AAG TAC AGT TAG TCT-3' and E2, 5'-ACG ATT CAA AGC TAA CTG-3'[18]. Primers for E. faecium EM1A, 5'-TTG AGG CAG ACCAGA TTG ACG-3' and EM1B, 5'-TAT GAC AGC GACTCC GAT TCC-3' [19]. PCR mixture (25 μl) contained 1 mM forward and reverse primers, dNTP mix (10 mM each of dATP, dCTP, dGTP and dTTP), 1 U of GO Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, USA), 5 μl green Go Taq buffer (5X), and DNA template (50 ng).

PCR products (5 μl) were analyzed on 1% (wt/v) agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/μl), visualized under ultraviolet transillumination and photographed using gel documentation systems InGenius (Syngene, USA).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Susceptibility to antibiotics was determined using the disc diffusion assay on Muller Hinton agar plates supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep blood, according to the "Comité de l'antibiogramme de la Société française de microbiologie" [20]. using the following antibiotics (diffusible amount): PenicillinG (10 UI), Amoxicillin (25 μg), Ampicillin (10 μg), Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid (20/10 μg), TIC: Ticarcillin (75 μg), Cefalotin (30 μg), Cefsulodin (30 μg), Ceftazidime (30 μg), Amikacin (30 μg), Gentamicin (500 μg), Kanamycin (1000 μg), Tobramycin (10 μg), Streptomycin (500 μg), Erythromycin (15 UI), Lincomycin (10 μg), Bacitracin (10 UI), Colistin (10 μg), Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole (1.25/23.75 μg), Nalidixic acid (30 μg), Ciprofloxacin (5 μg), Ofloxacin (5 μg), Nitroxolin (20 μg) and Vancomycin (30 μg).

After 18 h of incubation at 37°C, inhibition zone diameters around each disc were measured and the strains were categorized as resistant, intermediate resistant, or susceptible to the antimicrobial agents based on the inhibition zone size [20].

Phenotypic characterization of bacteria-producing slime

Qualitative Biofilm formation was studied by culturing strains on Congo red agar plate (CRA) made by mixing 36 g saccharose (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO) with 0.8 g Congo red in one litre of Brain heart infusion agar (Biorad, USA) and incubated at 37°C for 24 h under aerobic conditions [21].

Results were interpreted as follows: Very black, black and almost black colonies on CRA, were considered to be normal slime-producing strains, while very red, red and bordeaux were classified as non-slime-producing strains [22].

Semi quantitative adherence assay

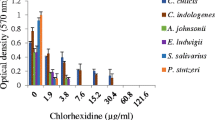

Quantitative Biofilm production by the isolated strains was determined using a semi-quantitative adherence assay as described previously [13, 23].

An overnight culture grown in BHI at 37°C was diluted to 1:100 in BHI with 2% glucose (w/v). A total of 200 μl of these cell suspensions was transferred in a U-bottomed 96-well microtiter plate (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). Wells with sterile BHI alone was served as negative control. Each strain was tested in triplicate.

The plates were incubated aerobically at 37°C for 24 h than the microtiter wells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and dried. Adherent bacteria were fixed with 95% ethanol and stained with 1% (w/v) crystal violet solution (Merck, France) for 5 min. The microplates were washed, air-dried and the optical density of each well was measured at 570 nm (OD570) using an automated Multiskan reader (GIO. DE VITA E C, Rome, Italy).

Biofilm formation was interpreted as follows: -: non-producer (OD570 < 0.120); +: weak producer (0.120 < OD570 < 0.240; ++: producer (0.240 < OD570 < 0.5) and +++: high producer (OD570 > 0.5) [24].

Adherence to human epithelial cells

Human epidermoid carcinoma epithelial cells (Hep-2; ATCC CCL-23) and the respiratory epithelial cell line (A549) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum (GIBCO-BRL) containing 1% penicillin (5 μg/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) and incubated with 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Cells (Hep-2 and A549) were seeded at a density of 5 × 105 /ml on glass coverslips placed in 24-well plates. All experiments were performed at 85-90% confluent cell monolayers. Prior to each experiment, the monolayer was washed with PBS and incubated with DMEM medium without antibiotics for 24 h. Overnight bacterial cultures were diluted at 1/100 into BHI broth and incubated at 37°C with agitation for approximately 2 h until the bacteria reached mid-log-phase. An aliquot of 100 μl of bacterial suspension of a density corresponding to approximately 2 × 106 CFU/ml was added to each cell. After incubation at 37°C for 3h, the coverslips were washed three times with PBS, fixed with methanol for 20 min, stained with Giemsa solution for 20 min and washed three times with PBS. Bacterial adherence to the cells was determined by light microscopy.

For each coverslip, a minimum of 800 cells was inspected to determine the percentage of infected cells, and next, 60-100 cells with bacteria were inspected to assess the number of cell associated bacteria. For each strain, two independent experiments were performed with two coverslips each [25]. Uninfected cells were included as a negative control.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed on SPSS v.17.0 statistics software. Pearson's chi-square χ2 test was used to assess inter-group significance. In addition Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Molecular identification of oral Enterococci

In this study 113 Gram positive cocci were isolated from the oral cavity of 62 Tunisian children. Molecular identification using specific primer showed the presence of 17 E. faecalis giving a 941 DNA base pair product upon amplification (Figure 1) and 4 E. faecium giving a 658 DNA base pair product (Figure 2).

Agarose gel electrophoresis of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of Enterococcus faecalis gene. Lane 1 and 6: 25 bp DNA molecular size marker; Lane 2, negative control; lanes 3 to 6, PCR amplicons obtained with DNA amplification of Enterococcus faecalis: lane 3, B54; lane 4, B9; lane 5, B310; lane 6, B403.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of Enterococcus faecium gene. Lane 1 and 6: 50 bp DNA molecular size marker; Lane 2, negative control; lanes 3 to 6, PCR amplicons obtained with DNA amplification of Enterococcus faecium: lane 3, B333; lane 4, B346; lane 5, B577; lane 6, B215.

Consequently, the prevalence of E. faecalis and E. faecium were 27.5% (17/62) and 6.5% (4/62) respectively (Table 1).

In the carious group population, the prevalence of E. faecalis and E. faecium were 46.9% (15/32) and 9.5% (3/32). However, in the caries-free one, the prevalence of E. faecalis and E. faecium were 7% (2/28) and 3.5% (1/28) respectively.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The antibiotic susceptibility of the isolated oral Enterococci showed the presence of multiresistant strains (Table 1).

Resistance profiles of Enterococci to the antimicrobial agents were as follows: penicillin, ticarcillin, Cefsulodin, Ceftazidime, Amikacin, Tobramycin and Streptomycin, 100%; Colistin, 91%, Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole, 71%, Ampicillin, 33%, Amoxicillin, 29%, Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid, Gentamicin and Kanamycin, 24%. Furthermore all the strains were susceptible to Cefalotin and Vancomycin.

Phenotypic characterization of bacteria-producing slime

Among the 17 isolated E. faecalis, 12 strains (71%) were slime producers developing almost black, black or very black colonies on the CRA plate and the remaining 5 strains were non-producers developing red or bordeaux colonies (Table 2).

Among the 4 E. faecium, 2 strains were slime producers developing almost black (B215) and very black colonies (B577) on the CRA plate.

Semi quantitative adherence assay

All the examined strains were biofilm producers using the semi quantitative adherence assay (Table 2) and the OD570 were above 0.12, i.e. the value recognized as the limit under which strains were considered non-producers [24]. Six isolates showed an OD570 higher than 0.5 (indicated as +++ in Table 2), this being the threshold for strongly biofilm producers.

Adherence of oral Enterococcito Hep-2 and A549 cells

Here, we analyzed the ability of Enterococcus strains isolated from oral cavity to adhere to the human epidermoid cancer (Hep-2) and the human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial (A549) cell lines. All the tested strains are able to adhere to at least one of the two tested cell lines.

Our result showed that 11 E. faecalis and 2 E. faecium strains adhered strongly to Hep-2 as well as to A549 cells (Table 2). Two strains were moderately adherent to both cells lines. In addition three strains were strongly adherent to Hep-2 cells while moderately adherent to A549 cells (Table 2).

Discussion

In the last decade, several studies have focused on the relationship between periodontal diseases and oral bacteria. The current investigation examined the prevalence of Enterococci in the oral cavity of Tunisian children using specific primers.

In this study, 21 Enterococci (33.9%) among 113 Gram positive cocci were isolated and identified from the oral cavity of 62 children. Nineteen Enterococci were isolated from carious lesion (55.8%) and two from caries free (7%). Similar results have been reported by Gold et al., [5] suggesting that Enterococci were detected in 60% of oral samples collected from carious school children.

Data presented in table 1 showed a significantly higher frequency of E. faecalis (n = 17) than E. faecium (n = 4). This result was contradictory with a recent study reported a low prevalence rate of E. faecalis (3.5% to 13.5%) in intraoral sites [26].

Antimicrobial agents are frequently used in dentistry [27], which may however lead to drug resistance among the other oral bacteria [28]. In this study, the isolated strains were examined for their antimicrobial susceptibility to a broad range of antibiotics. Our results revealed the presence of resistant Enterococci (E. faecalis and E. faecium) to a wide range of antibiotics such as penicillin, Ticarcillin, Cefsulodin, Ceftazidime, Amikacin, Tobramycin, streptomycin, erythromycin, Lincomycin, Bacitracin, Nalidixic acid, Ciprofloxacin, Ofloxacin and Nitroxolin (Table 1). This is a serious problem, as it reduces the number of possible antimicrobial therapies for dental infections associated to Enterococci. Furthermore all the isolated strains were susceptible to Cefalotin and Vancomycin. Resistant Enterococci to currently available antibiotics pose real therapeutic difficulties [29] and can lead to the endodontic treatment failures result [30]. Moreover, transfer of resistance determinants from Enterococci to other more virulent Gram-positive bacteria, like staphylococci, has been observed in vitro [31]. Our previous data supported the presence of resistance oral streptococci [32] and the association of Staphylococcus aureus with dental caries [33] which carried various antibiotics and disinfectants resistance genes [34].

E. faecalis is responsible for endodontic infections due to their adherence to dentin collagen, and their resistance to endodontic therapy [26].

Enterococci are the third most common pathogen isolated from bloodstream infections and the most frequently isolated species in teeth with persistent infection after root canal treatment [35]. Different bacteriological studies have evaluated that E. faecalis is present in 29-46% of root-filled teeth with periapical lesions [36]. These findings highlight the ability of E. faecalis to persist in the post endodontic root canal environment [37]. One of the virulence factors that allow Enterococci to persist within the oral cavity is biofilm formation. Oral Enterococci produce virulence factors including aggregation substances, surface adhesins, lytic enzymes, and haemolysins [38]. The prevalence of biofilm positive Enterococci varied worldwide. Many studies have reported the ability of Enterococcus derived from various clinical origins to form biofilm [24]. Thus, biofilm formation may be an important factor in the pathogenesis of enterococcal infection.

Our data showed that 71% of E. faecalis and 50% of E. faecium were slimes producer on CRA plates. Moreover, all the examined strains were biofilm producers on microtiter plate (OD570 > 0.120). Statistical analysis revealed a correlation between the slime production on CRA and the semi quantitative adherence assay value (P < 0.001). Similar results have been reported by Arciola et al., [24] who confirmed that the majority of E. faecalis isolated from orthopedic implant-related infections are able to form biofilm.

Quantitative adherence determination showed a wide range of variation in adherence among strains, and the one sample-t test revealed a significant difference in adherence potency between the tested strains (P < 0.001).

A number of adhesion factors of Enterococci have been identified that confer binding to mucosal and other epithelial surfaces and facilitate host colonization [39]. Aggregation substance seems to mediate the specific binding of Enterococci to intestinal epithelium [40], renal epithelial cells [41], and macrophages [42] which increase their intracellular survival [42]. Since Enterococci are among the leading causes of endocarditis, and also exist as opportunistic bacteria in the oral cavity, bacterial adherence assay was performed to assess the binding efficiency of Enterococci to Hep2 and A549 cells.

All the isolated bacteria adhered to host cells. Among them16 and 13 strains were defined as strongly adherent to Hep-2 and A549 cells respectively (Table 2) confirming previous restudy suggesting the adherence ability of Enterococci to many host cells especially cardiac (GH), urinary tract epithelial cells (Vero, HEK) and intestinal cells [43].

At this point, we succeeded to establish a correlation between the semi quantitative adherence assay and the adherence potency to Hep2 and A549 cells (P < 0.001). The high adherence level of oral Enterococci to host cells increases their pathogenecity and confirms the role of the oral cavity as a reservoir of bacterial pathogens for focal infections.

Conclusion

In summary, the oral cavity has been shown to be a reservoir for drug-resistant Enterococci. More importantly, our findings provide additional evidence for the persistence and adherence abilities of these bacteria within the carious lesions. The high rate of drugs resistance, strong biofilm formers and strong adherent to host cells Enterococci suggests that these three factors may play an important role in enterococcal infections. The establishment of such pathogen in the dental biofilm in addition to its multi-resistance, close attention should be given to these strains in order to reduce the risk for development of systemic diseases caused by Enterococci in other areas of the body.

References

Jett BD, Huycke MM, Gilmore MS: Virulence of enterococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994, 7: 462-478.

Huycke MM, Sahm DF, Gilmore MS: Multiple-drug resistant enterococci: the nature of the problem and an agenda for the future. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998, 4: 239-249. 10.3201/eid0402.980211.

Tannock GW, Cook G: Enterococci as members of the intestinal microflora of humans. Edited by: Gilmore MS. 2002, The enterococci: pathogenesis molecular biology and antibiotic resistance Washington, DC: ASM Press, 101-132.

Sedgley C, Buck G, Appelbe O: Prevalence of Enterococcus faecalis at multiple oral sites in endodontic patients using culture and PCR. J Endod. 2006, 32: 104-109. 10.1016/j.joen.2005.10.022.

Gold OG, Jordan HV, van Houte J: The prevalence of enterococci in the human mouth and their pathogenicity in animal models. Arch Oral Biol. 1975, 20: 473-477. 10.1016/0003-9969(75)90236-8.

Sedgley CM, Lee EH, Martin MJ, Flannagan SE: Antibiotic resistance gene transfer between Streptococcus gordonii and Enterococcus faecalis in root canals of teeth ex vivo. J Endod. 2008, 34: 570-574. 10.1016/j.joen.2008.02.014.

Aas JA, Paster BJ, Stokes LN, Olsen I, Dewhirst FE: Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol. 2005, 43: 5721-5732. 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5721-5732.2005.

Rocas IN, Siqueira JF, Santos KR: Association of Enterococcus faecalis with different forms of periradicular diseases. J Endod. 2004, 30: 315-320. 10.1097/00004770-200405000-00004.

Schirrmeister JF, Liebenow AL, Pelz K, Wittmer A, Serr A, Hellwig E, Al-Ahmad A: New bacterial compositions in root-filled teeth with periradicular lesions. J Endod. 2009, 35: 169-174.

Al-Ahmad A, Maier J, Follo M, Spitzmuller B, Wittmer A, Hellwig E, Hubner J, Jonas D: Food-borne enterococci integrate into oral biofilm: an in vivo study. J Endod. 2010, 36: 1812-1819. 10.1016/j.joen.2010.08.011.

Standar K, Kreikemeyer B, Redanz S, Munter WL, Laue M, Podbielski A: Setup of an in vitro test system for basic studies on biofilm behavior of mixed-species cultures with dental and periodontal pathogens. PLoS One. 2010, 5 (10):

Mohamed JA, Huang DB: Biofilm formation by enterococci. J Med Microbiol. 2007, 56: 1581-1588. 10.1099/jmm.0.47331-0.

Baldassarri L, Cecchini R, Bertuccini L, Ammendolia MG, Iosi F, Arciola CR, Montanaro L, Di Rosa R, Gherardi G, Dicuonzo G, et al: Enterococcus spp. produces slime and survives in rat peritoneal macrophages. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2001, 190: 113-120.

Sandoe JA, Witherden IR, Cove JH, Heritage J, Wilcox MH: Correlation between enterococcal biofilm formation in vitro and medical-device-related infection potential in vivo. J Med Microbiol. 2003, 52: 547-550. 10.1099/jmm.0.05201-0.

Tomita H, Ike Y: Tissue-specific adherent Enterococcus faecalis strains that show highly efficient adhesion to human bladder carcinoma T24 cells also adhere to extracellular matrix proteins. Infect Immun. 2004, 72: 5877-5885. 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5877-5885.2004.

Shiono A, Ike Y: Isolation of Enterococcus faecalis clinical isolates that efficiently adhere to human bladder carcinoma T24 cells and inhibition of adhesion by fibronectin and trypsin treatment. Infect Immun. 1999, 67: 1585-1592.

Guzman CA, Pruzzo C, LiPira G, Calegari L: Role of adherence in pathogenesis of Enterococcus faecalis urinary tract infection and endocarditis. Infect Immun. 1989, 57: 1834-1838.

Dutka-Malen S, Evers S, Courvalin P: Detection of glycopeptide resistance genotypes and identification to the species level of clinically relevant enterococci by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995, 33: 1434-

Cheng S, McCleskey FK, Gress MJ, Petroziello JM, Liu R, Namdari H, Beninga K, Salmen A, DelVecchio VG: A PCR assay for identification of Enterococcus faecium. J Clin Microbiol. 1997, 35: 1248-1250.

CASFM: Comité de l'antibiogramme de Société française de microbiologie. Report of the comité de l'antibiogramme de Société française de microbiologie. Technical recommendations for in vitro susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1996, 2: 11-25.

Freeman DJ, Falkiner FR, Keane CT: New method for detecting slime production by coagulase negative staphylococci. J Clin Pathol. 1989, 42: 872-874. 10.1136/jcp.42.8.872.

Arciola CR, Campoccia D, Gamberini S, Cervellati M, Donati E, Montanaro L: Detection of slime production by means of an optimised Congo red agar plate test based on a colourimetric scale in Staphylococcus epidermidis clinical isolates genotyped for ica locus. Biomaterials. 2002, 23: 4233-4239. 10.1016/S0142-9612(02)00171-0.

Christensen GD, Simpson WA, Younger JJ, Baddour LM, Barrett FF, Melton DM, Beachey EH: Adherence of coagulase-negative staphylococci to plastic tissue culture plates: a quantitative model for the adherence of staphylococci to medical devices. J Clin Microbiol. 1985, 22: 996-1006.

Arciola CR, Baldassarri L, Campoccia D, Creti R, Pirini V, Huebner J, Montanaro L: Strong biofilm production, antibiotic multi-resistance and high gelE expression in epidemic clones of Enterococcus faecalis from orthopaedic implant infections. Biomaterials. 2008, 29: 580-586. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.008.

Lee JC, Koerten H, van den Broek P, Beekhuizen H, Wolterbeek R, van den Barselaar M, van der Reijden T, van der Meer J, van de Gevel J, Dijkshoorn L: Adherence of Acinetobacter baumannii strains to human bronchial epithelial cells. Res Microbiol. 2006, 157: 360-366. 10.1016/j.resmic.2005.09.011.

Estrela CR, Pimenta FC, Alencar AH, Ruiz LF, Estrela C: Detection of selected bacterial species in intraoral sites of patients with chronic periodontitis using multiplex polymerase chain reaction. J Appl Oral Sci. 2010, 18: 426-431. 10.1590/S1678-77572010000400018.

Stuart CH, Schwartz SA, Beeson TJ, Owatz CB: Enterococcus faecalis: its role in root canal treatment failure and current concepts in retreatment. J Endod. 2006, 32: 93-98.

Cavalca Cortelli S, Cavallini F, Regueira Alves MF, Alves Bezerra A, Queiroz CS, Cortelli JR: Clinical and microbiological effects of an essential-oil-containing mouth rinse applied in the "one-stage full-mouth disinfection" protocol-a randomized doubled-blinded preliminary study. Clin Oral Investig. 2009, 13: 189-194. 10.1007/s00784-008-0219-3.

Richards MJ, Edwards JR, Culver DH, Gaynes RP: Nosocomial infections in combined medical-surgical intensive care units in the United States. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000, 21: 510-515. 10.1086/501795.

Siqueira JF: Endodontic infections: concepts, paradigms, and perspectives. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002, 94: 281-293. 10.1067/moe.2002.126163.

Murray BE: Vancomycin-resistant enterococcal infections. N Engl J Med. 2000, 342: 710-721. 10.1056/NEJM200003093421007.

Kouidhi B, Zmantar T, Hentati H, Najjari F, Mahdouni K, Bakhrouf A: Molecular investigation of macrolide and Tetracycline resistances in oral bacteria isolated from Tunisian children. Arch Oral Biol. 2010, 56: 127-35.

Kouidhi B, Zmantar T, Hentati H, Bakhrouf A: Cell surface hydrophobicity, biofilm formation, adhesives properties and molecular detection of adhesins genes in Staphylococcus aureus associated to dental caries. Microb Pathog. 2010, 49: 14-22. 10.1016/j.micpath.2010.03.007.

Zmantar T, Kouidhi B, Hentati H, Bakhrouf A: Detection of disinfectant and antibiotic resistance genes in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from the oral cavity of Tunisian children. Annals of Microbiology. 2011

Sedgley CM, Lennan SL, Clewell DB: Prevalence, phenotype and genotype of oral enterococci. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2004, 19: 95-101. 10.1111/j.0902-0055.2004.00122.x.

Sedgley CM, Nagel AC, Shelburne CE, Clewell DB, Appelbe O, Molander A: Quantitative real-time PCR detection of oral Enterococcus faecalis in humans. Arch Oral Biol. 2005, 50: 575-583. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.10.017.

Hancock HH, Sigurdsson A, Trope M, Moiseiwitsch J: Bacteria isolated after unsuccessful endodontic treatment in a North American population. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001, 91: 579-586. 10.1067/moe.2001.113587.

Kayaoglu G, Orstavik D: Virulence factors of Enterococcus faecalis: relationship to endodontic disease. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2004, 15: 308-320. 10.1177/154411130401500506.

Koch S, Hufnagel M, Theilacker C, Huebner J: Enterococcal infections: host response, therapeutic, and prophylactic possibilities. Vaccine. 2004, 22: 822-830. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.11.027.

Sartingen S, Rozdzinski E, Muscholl-Silberhorn A, Marre R: Aggregation substance increases adherence and internalization, but not translocation, of Enterococcus faecalis through different intestinal epithelial cells in vitro. Infect Immun. 2000, 68: 6044-6047. 10.1128/IAI.68.10.6044-6047.2000.

Kreft B, Marre R, Schramm U, Wirth R: Aggregation substance of Enterococcus faecalis mediates adhesion to cultured renal tubular cells. Infect Immun. 1992, 60: 25-30.

Sussmuth SD, Muscholl-Silberhorn A, Wirth R, Susa M, Marre R, Rozdzinski E: Aggregation substance promotes adherence, phagocytosis, and intracellular survival of Enterococcus faecalis within human macrophages and suppresses respiratory burst. Infect Immun. 2000, 68: 4900-4906. 10.1128/IAI.68.9.4900-4906.2000.

Archimbaud C, Shankar N, Forestier C, Baghdayan A, Gilmore MS, Charbonné F, Jolya B: In vitro adhesive properties and virulence factors of Enterococcus faecalis strains. Research in Microbiology. 2002, 153: 75-80. 10.1016/S0923-2508(01)01291-8.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Hassane Rashed, Monastir Sciences Palace, Languages Lab trainer and in charge of the Languages lab and training programmes consultant, for his assistance to improve the English of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

BK was the primary author of the manuscript, assisted in samples collection, molecular identification of oral Enterococci, antimicrobial susceptibility, biofilms and adherence assay.

TZ was the person contributed in biofilms assay and helped in the writing of the manuscript.

KM was the person who participated in data acquisition and contributed in writing the manuscript. HH helped in samples collection, designed and participated in the writing of the manuscript. AB provided funding, supervised the study, and helped to finalize the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial competing interests

Ministère Tunisien de l'Enseignement Supérieur, de la Recherche Scientifique'' through the ''Laboratoire d'Analyses, Traitement et Valorisation des Polluants de l'Environnement et des Produits, Faculté de Pharmacie, rue Avicenne 5000 Monastir (Tunisie).

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kouidhi, B., Zmantar, T., Mahdouani, K. et al. Antibiotic resistance and adhesion properties of oral Enterococci associated to dental caries. BMC Microbiol 11, 155 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-11-155

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-11-155