Abstract

Background

Quorum sensing is a communication system that regulates gene expression in response to population density and often regulates virulence determinants. Deletion of the luxR homologue vjbR highly attenuates intracellular survival of Brucella melitensis and has been interpreted to be an indication of a role for QS in Brucella infection. Confirmation for such a role was suggested, but not confirmed, by the demonstrated in vitro synthesis of an auto-inducer (AI) by Brucella cultures. In an effort to further delineate the role of VjbR to virulence and survival, gene expression under the control of VjbR and AI was characterized using microarray analysis.

Results

Analyses of wildtype B. melitensis and isogenic ΔvjbR transciptomes, grown in the presence and absence of exogenous N-dodecanoyl homoserine lactone (C12-HSL), revealed a temporal pattern of gene regulation with variances detected at exponential and stationary growth phases. Comparison of VjbR and C12-HSL transcriptomes indicated the shared regulation of 127 genes with all but 3 genes inversely regulated, suggesting that C12-HSL functions via VjbR in this case to reverse gene expression at these loci. Additional analysis using a ΔvjbR mutant revealed that AHL also altered gene expression in the absence of VjbR, up-regulating expression of 48 genes and a luxR homologue blxR 93-fold at stationary growth phase. Gene expression alterations include previously un-described adhesins, proteases, antibiotic and toxin resistance genes, stress survival aids, transporters, membrane biogenesis genes, amino acid metabolism and transport, transcriptional regulators, energy production genes, and the previously reported fliF and virB operons.

Conclusions

VjbR and C12-HSL regulate expression of a large and diverse number of genes. Many genes identified as virulence factors in other bacterial pathogens were found to be differently expressed, suggesting an important contribution to intracellular survival of Brucella. From these data, we conclude that VjbR and C12-HSL contribute to virulence and survival by regulating expression of virulence mechanisms and thus controlling the ability of the bacteria to survive within the host cell. A likely scenario occurs via QS, however, operation of such a mechanism remains to be demonstrated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Brucella spp. are Gram-negative, non-motile, facultative intracellular bacterial pathogens that are the etiologic agents of brucellosis, causing abortion and sterility in a broad range of domestic and wild animals. Furthermore, brucellosis is a chronic zoonotic disease characterized in humans by undulant fever, arthritic pain and neurological disorders. Brucella virulence relies upon the ability to enter phagocytic and non-phagocytic cells, control the host's intracellular trafficking to avoid lysosomal degradation, and replicate in a Brucella-containing vacuole (brucellosome) without restricting host cell functions or inducing programmed death [1–3]. Although a few genes are directly attributed to the survival and intracellular trafficking of Brucella in the host cell (e.g., cyclic β-(1,2) glucan, lipopolysaccharide and the type IV secretion system (T4SS)), many aspects of the intracellular lifestyle remain unresolved [4–6].

Quorum sensing (QS), a communication system of bacteria, has been shown to coordinate group behavior in a density dependent manner by regulating gene expression; including secretion systems, biofilm formation, AI production, and cell division [7–10]. QS typically follows production of a diffusible signaling molecule or autoinducer (AI) acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL). Among proteobacteria, the larger family to which Brucella belong, the AHL signal is synthesized by luxI, and shown to interact with the transcriptional regulator LuxR to cooperatively modulate gene expression [9]. In addition to an AHL signal, LuxR regulatory activity can be modulated by phosphorylation (fixJ), contain multiple ligand binding sites (malT), or LuxR can function as an autonomous effector without a regulatory domain (gerE) [11–13].

Two LuxR-like transcriptional regulators, VjbR and BlxR (or also referred to as BabR) have been identified in Brucella melitensis [14, 15]. VjbR was shown to positively influence expression of the T4SS and flagellar genes, both of which contribute to B. melitensis virulence and survival [14]. Although an AHL signal N- dodecanoyl homoserine lactone (C12-HSL) has been purified from Brucella culture supernatants, the gene responsible for the production of this AHL (luxI) has not yet been identified [16]. One possible explanation for the apparent absence of luxI homologues is that Brucella contains a novel AHL synthetase that remains to be identified. The fact that both LuxR homologues respond to C12-HSL by altering the expression of virulence determinants is also consistent with a role for the autoinducer in regulating expression of genes necessary for intracellular survival [17, 18]. Specifically, expression of the virB and flgE operons are repressed by the addition of exogenous C12-HSL [14, 16]. The results reported here extend those observations and suggest that C12-HSL acts as a global repressor of gene expression via interaction with VjbR while functioning to activate expression of other loci independent of VjbR.

In the present study, we sought to identify additional regulatory targets of the putative QS components VjbR and C12-HSL in an effort to identify novel virulence factors to confirm a role for QS in intracellular survival. Custom B. melitensis 70-mer oligonucleotide microarrays were utilized to characterize gene expression. Comparison of transcript levels from B. melitensis wildtype and a vjbR deletion mutant, with and without the addition of exogenous C12-HSL revealed a large number of genes not previously shown to be regulated in B. melitensis, including those involved in numerous metabolic pathways and putative virulence genes (e.g., adhesins, proteases, lipoproteins, outer membrane proteins, secretion systems and potential effector proteins). Additionally, results confirmed earlier findings of genes regulated by these components, validating the microarray approach for identification of genes that may contribute to intracellular survival and virulence.

Methods

Bacteria, macrophage strains and growth conditions

Escherichia coli DH5α™-T1R competent cells were used for cloning and routinely grown on Luria-Bertani (LB, Difco Laboratories) overnight at 37°C with supplemental kanamycin (100 mg/l) or carbenicillin (100 mg/l) as needed. B. melitensis 16M was grown on tryptic soy agar or broth (TSA or TSB) and J774A.1 murine macrophage-like cells were maintained in T-75 flasks in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, HEPES modification (DMEM), supplemented with 1× MEM non-essential amino acids (Sigma, St Louis, MO), 0.37% sodium bicarbonate and 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C with 5% CO2. All work with live B. melitensis was performed in a biosafety level 3 laboratory at Texas A&M University College Station, per CDC approved standard operating procedures. All bacterialstrains used are listed in Additional File 1, Table S1.

Generation of gene replacement and deletion mutants

LuxR-like proteins were identified in B. melitensis using NCBI BLAST protein homology searches http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. B. melitensis 16M luxR gene replacement and deletion mutations were created as previously described by our laboratory, with plasmids and strains generated described in Additional File 1, Table S1 and primers for PCR applications listed in Additional File 2, Table S2 [19]. For complementation of the ΔvjbR mutation, gene locus BMEII1116 was amplified by PCR primers TAF588 and TAF589, cloned into pMR10-Kan Xba I sites, and electroporated into B. melitensis 16MΔvjbR (Additional File 1, Table S1 and Additional File 2, Table S2).

Gentamycin protection assay

J774A.1 cells were seeded into 24-well plates at a density of 2.5 × 105 CFU/well and allowed to rest for 24 hours in DMEM. J774A.1 cells were infected with B. melitensis 16M or mutant strains in individual wells at an MOI of 20. Following infection, monolayers were centrifuged (200 × g) for 5 min and incubated for 20 minutes. Infected monolayers were washed 3 × in Peptone Saline (1% Bacto-Peptone and 0.5% NaCl), and incubated in DMEM supplemented with gentamycin (40 μg/ml) for 1 hour. To collect internalized bacteria at time 0 and 48 hours post-infection, macrophages were lysed in 0.5% Tween-20 and serial dilutions were plated to determine bacterial colony forming units (CFU).

RNA collection

Cultures were grown in Brucella Broth at 37°C with agitation. Cultures for the AHL experiments were grown with the addition of exogenous N-dodecanoylhomoserine lactone (C12-HSL, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) added at inoculation (50 ng/ml) dissolved in DMSO (at a final concentration of 0.008%) [16]. Total RNA was extracted at mid-exponential (OD600 = 0.4) and early stationary (OD600 = 1.5) growth phases by hot acidic phenol extraction, as previously described [20]. Contaminating DNA was degraded by incubation with DNAseI (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following manufacturer's instructions and purified using the HighPure RNA isolation kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). RNA integrity, purity and concentration were evaluated using a 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara CA), electrophoresis, and the Nanodrop® ND-1000 (Nanodrop, Wilmington, DE).

DNA and RNA labeling for microarrays

B. melitensis 16M genomic DNA was processed into cDNA using the BioPrime® Plus Array CGH Indirect Genomic Labeling System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and purified using PCR purification columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions and eluted in 0.1× of the supplied elution buffer.

The cDNA synthesis from total RNA was produced using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase kit following manufacturer instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Reactions were subsequently purified with PCR Purification columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) using a modified wash (5 mM KPO4 (pH 8.0) and 80% ethanol) and incremental elution with 4 mM KPO4, pH 8.5. Alexa-Fluor 555 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was coupled to the RNA-derived cDNA following the procedure outlined in the BioPrime® Plus Array CGH Indirect Genomic Labeling System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and purified using PCR purification columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Labeled RNA samples were dried completely and re-suspended in ddH2O immediately before hybridization to the microarrays.

Microarray construction

Unique 70-mer oligonucleotides (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) representing 3,227 ORFs of B. melitensis 16M and unique sequences from B. abortus and B. suis were suspended in 3× SSC (Ambion, Austin, TX) at 40 μM. The oligonucleotides were spotted in quadruplicate onto ultraGAP glass slides (Corning, Corning, NY) by a custom-built robotic arrayer (Magna Arrayer) assembled at Dr. Stephen A. Johnston's lab at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, TX). The printed slides were steamed, UV cross-linked, and stored in a desiccator until use.

Microarray pre-hybridization, hybridization and washing

Printed slides were submerged in 0.2% SDS for 2 minutes and washed 3× in ddH2O before incubation in prehybridization solution (5× SSC, 0.1% SDS and 1% BSA) at 45°C for 45 minutes. Next, slides were washed 5× in ddH2O, rinsed with isopropanol, and immediately dried by centrifugation at 200 × g for 2 minutes at room temperature. The labeled cDNA mix was combined with 1× hybridization buffer (25% formamide, 1× SSC and 0.1%SDS) and applied to the microarray in conjunction with a 22 × 60 mm LifterSlip (Erie Scientific, Portsmouth, NH). The microarray slides were hybridized at 42°C for approximately 21 hours in a sealed hybridization chamber with moisture (Corning, Corning, NY), and subsequently washed at room temperature with agitation in 2× SSC and 0.2% SDS (pre-heated to 42°C) for 10 minutes, 5 minutes in 2× SSC, followed by 0.2× SSC for 5 minutes, and dried by centrifugation for 2 minutes (200 × g) at room temperature.

Microarray data acquisition and analysis

Array slides were scanned using GenePix 4100A (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and GenePix 6.1 Pro software. Seralogix, Inc. (Austin, TX) performed microarray analysis, normalizing the data and identifying differentially expressed genes by a two-tail z-score level greater than ± 1.96, equating to a confidence level of 95%. Additionally, the NIH/NIAID WRCE bioinformatics core performed microarray analysis as follows: GeneSifter (VizX Labs, Seattle, WA) was used to perform normalization based on the global mean and genes with alterations of least a 1.5-fold, with a p value of 0.05 or less based on Student's t-test were deemed as statistically significant. Any gene that was considered statistically significant based on Student's t-test but not by the z-score criteria were further expected to be at least 50% greater in magnitude (e.g., 1.5-fold greater) than the fold-change observed between any two biological replicate samples. All gene expression data have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE13634.

Quantitative real time PCR

Taqman® universal probes and primer pairs (Additional File 2, Table S2) were selected using Roche's Universal Probe Library and probefinder software http://www.universalprobelibrary.com. RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) andPCR reactions consisted of 1× TaqMan® universal PCR master mix, no AmpErase® UNG (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), 200 nM of each primer and 100 nM of probe. With the exception of BMEI1758, genes were selected at random for quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) verification, and were performed in triplicate for each sample within a plate and repeated 3× using the 7500 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Gene expression was normalized to that of 16s rRNA and the fold-change calculated using the comparative threshold method [21].

Screen for a putative AHL synthase

Fifteen B. melitensis genetic loci and P. aeruginosa lasI and rhlI were amplified by PCR, cloned into BamH I sites in the pET-11a expression vector and transformed by heat-shock into E. coli BL21-Gold(DE3) cells (Additional File 1, Table S1 and Additional File 2, Table S2). The resulting clones were cross streaked on LB agar supplemented with 2 mM IPTG with E. coli JLD271 + pAL105 and pAL106 for detection of C12-HSL production, and E. coli JLD271 + pAL101 and pAL102 for detection of C4-HSL production (Additional File 1, Table S1). Cross-streaks were incubated at 37°C for 2-8 hours, and luminescence was detected using the FluorChem Imaging System (Alpha-Innotech, San Leandro, CA) at varied exposure times.

Results and Discussion

Identification and screening for attenuation of ΔluxR mutants in J774A.1 macrophage-like cells

A luxR-like gene, vjbR, was identified in a mutagenesis screen conducted by this laboratory and others [22]. More recently, a second luxR- like gene, blxR (or babR), has also been identified and characterized [15, 23]. These two homologues, VjbR and BlxR, contain the two domains associated with QS LuxR proteins (i.e., autoinducer binding domain and LuxR DNA binding domain). BLAST protein homology searches with the LuxR-like proteins identified three additional proteins that contain significant similarity to the LuxR helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA binding domain but do not contain the AHL binding domain. All 5 B. melitensis LuxR-like proteins exhibit similar levels of relatedness to Agrobacterium tumefaciens TraR homolog (29-34%) and canonical LuxR homolog LasR from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (29-43%). Despite the absence of a characterized activation domain, evaluation of these three proteins was pursued due to their similarity with LuxR homologs best characterized in Vibrio harveyi that act autonomously or via phosphorylation/dephosphorylation to alter gene expression from selected loci [24, 25].

Gene replacement and deletion mutations were created for all five homologues including the three newly discovered HTH LuxR DNA binding domain homologues (BME I1582, I1751 and II0853), vjbR, and blxR in B. melitensis 16M and survival in J774A.1 macrophage-like cells was subsequently assessed by gentamycin protection assays. Confirming previous findings, intracellular survival was significantly reduced for both the vjbR transposon and deletion mutants and not for the blxR mutant, as indicated by CFU recovery after 48 hrs of infection (Fig. 1) [14, 23]. Survival of the vjbR mutant was restored to nearly wildtype levels after complementation (Fig. 1). No significant difference in CFU was observed for the other three mutants when compared to wildtype infected cells, indicating that these homologues are either not required for intracellular replication in macrophages or there is functional redundancy among some of homologues (Fig. 1). A recent report presented evidence indicating that the ΔblxR and ΔvjbR mutants exhibited similar levels of attenuated intracellular survival in the RAW264.7 macrophage cells [15]. However, the ΔblxR mutant proved to be virulent in IRF1-/- knockout mice, with only a slight delay in mortality when compared to wildtype (10 days vs. 7.4, respectively) [15]. For comparison, all of the mice inoculated with the ΔvjbR mutant survived to at least day 14 [15]. Taken together the results suggest that the loss of blxR expression has only a modest effect on virulence/survival and the attenuated phenotype of the ΔvjbR mutant is more consistently observed.

Intracellular survival of B. melitensis 16M (wt), vjbR mutant (Δ vjbR and vjbR ::m Tn 5), complemented Δ vjbR (Δ vjbR comp and Δ vjbRvector ), Δ blxR mutant, and 3 additional luxR -like mutants in J774A.1 murine macrophage-like cells. The attenuation was measured as the log difference between the CFU recoveries of the mutant compared to wildtype from infected macrophages at 48 hours post infection. Data shown is the averaged CFU recovery from at least 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. Error bars represent the SEM and each mutant was compared to the wildtype by a Student's two tailed t-test, with the resulting p values as follows:*, P < .0.05; ***, P < 0.001. The luxR deletion mutant strains are identified by the BME gene locus ID tags, BME::Km representing the gene replacement mutant and ΔBME representing the gene deletion mutant.

Microarray analysis indicates that Brucella putative quorum sensing components are global regulators of gene expression

To investigate the transcriptional effects resulting from a vjbR deletion and the addition of exogenous C12-HSL, RNA was isolated from wildtype B. melitensis 16M, the isogenic ΔvjbR, and both strains with the addition of exogenous C12-HSL, at a logarithmic growth phase and an early stationary growth phase. The use of exogenous C12-HSL addition to cultures was selected because of the inability to eliminate the gene(s) responsible for C12-HSL production. Three independent RNA samples were harvested at each time point (exponential and early stationary growth phases) and hybridized with reference genomic DNA, which yielded a total of 24 microarrays.

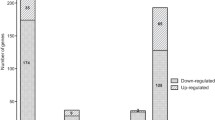

Microarray analysis revealed a total of 202 (Fig. 2A, blue circles) and 229 genes (Fig. 2B, blue circles) to be differentially expressed between wildtype and ΔvjbR cultures at exponential and stationary growth phases, respectively (details provided in Additional File 3, Table S3). This comprises 14% of the B. melitensis genome and is comparable to the value of 10% for LuxR-regulated genes previously predicted for in P. aeruginosa [26]. The majority of altered genes at the exponential phase were down-regulated (168 genes) in the absence of vjbR, while only 34 genes were up-regulated (Fig. 2A, blue circles). There were also a large number of down-regulated genes (108 genes) at the stationary phase; however, at this later time point there were also 121 genes that were specifically up-regulated (Fig. 2B, blue circles). When comparing wild-type cells with and without the addition of exogenous C12-HSL, the majority of genes were found to be down-regulated at both growth phases, 249 genes at exponential phase (Fig. 2A, green circle) and 89 genes at stationary phase (Fig. 2B, green circle). These data suggest that VjbR is primarily a promoter of gene expression at the exponential growth phase and acts as both a transcriptional repressor and activator at the stationary growth phase. Conversely, C12-HSL primarily represses gene expression at both growth phases.

Numbers and relationships of transcripts altered by the deletion of vjbR and/or treatment of C12-HSL. Numbers represent the statistically significant transcripts found to be up or down-regulated by microarray analysis at the A) exponential growth phase (OD600 = 0.4) and B) stationary growth phase (OD600 = 1.5).

Quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed to verify the changes in gene expression for 11 randomly selected genes found to be altered by the microarray analyses (Table 1). For consistency across the different transcriptional profiling assays, cDNA was synthesized from the same RNA extracts harvested for the microarray experiments. For the 11 selected genes, the relative transcript levels were comparable to the expression levels obtained from the microarray data.

Recently, a virB promoter sequence was identified and confirmed to promote expression of downstream genes via VjbR [27]. With such a large number of transcriptional regulators found to be altered downstream of VjbR and by the addition of C12-HSL (Table 2), it is plausible that many of the gene alterations observed may be downstream events and not directly regulated by VjbR. To identify altered genes that are likely directly regulated by VjbR, microarray data from these studies were compared to the potential operons downstream of the predicted VjbR promoter sequences [27]. A total of 91 potential operons from the 144 previously predicted VjbR promoter sequences were found to be altered by a deletion of VjbR and/or treatment of wildtype cells with C12-HSL, comprised of 215 genes (Additional File 4, Table S4) [27]. A total of 11 promoters from the confirmed 15 found to be activated by VjbR in an E. coli model were identified in the microarray analyses conducted in this study, confirming the direct regulation of these particular operons (Additional File 4, Table S4) [27].

The differentially expressed genes were categorized by clusters of orthologous genes (COGs), obtained from the DOE Joint Genome Institute Integrated Microbial Genomics project http://img.jgi.doe.gov/cgi-bin/pub/main.cgi. This classification revealed categories that were equally altered by both the vjbR mutant and addition of C12-HSL to wildtype bacteria (Fig. 3). For example; defense mechanisms, intracellular trafficking and secretion were highly over-represented when compared to genomic content. Of particular note, genes involved in cell division were found to be over-represented in wildtype bacteria grown in the presence of C12-HSL but not by deletion of vjbR, indicating that C12-HSL regulates cellular division and may play a key role in the intracellular replication of the bacteria.

COG functional categories found to be over and under represented by the deletion of vjbR and the addition of C 12 -HSL to wildtype cells, indicated by microarray analyses. Ratios were calculated by comparing the proportion of genes found to be altered by the putative QS component to the total number of genes classified in each COG category present in the B. melitensis genome.

Genes found to be altered by deletion of vjbR and treatment with C12-HSL in both wildtype and ΔvjbR backgrounds were compared to data compiled from random mutagenesis screenings, resulting in the identification of 61 genes (Tables 2,3,4 and Additional File 3, Table S3) [22, 28, 39]. This correlation strongly suggests that VjbR and C12-HSL are involved not only in regulating the expression of a diverse array of genes but numerous genetic loci that individually make significant contributions to the intracellular survival of Brucella spp.

VjbR and C12-HSL modulate gene transcription in a temporal manner

Comparison of altered gene transcripts resulting from the ΔvjbR mutation revealed that 13% (54 statistically significant genes) were found to be regulated at both growth phases, suggesting that VjbR exerts temporal control over gene regulation (Additional File 3, Table S3). A similar subset of genes were also identified in wildtype bacteria that were treated with C12-HSL when compared to those without treatment, with 12% (54 genes, Additional File 3, Table S3) of transcripts altered at both growth stages. The low correlation of genes altered at both growth stages suggests that both VjbR and C12-HSL regulate distinct regulons at the two growth stages examined.

A recent study compared microarray and proteomic data from a ΔvjbR mutant at a late exponential growth phase (OD600 = 0.75), corresponding to a total of 14 genes and the virB operon found at the growth phases examined here [23]. Of the 14 genes in common with the study by Uzureau et al.; 2 genes and the virB operon identified in our study (BMEI1435 and I1939) correlated in the magnitude of change with both the protein and microarray data, BMEI1267 correlated with the protein data, and 3 genes (BMEI1900, II0358 and II0374) correlated with the microarray data (Additional File 3, Table S3) [23]. Additionally, 5 genes did not correspond with the magnitude of alteration in the microarray analyses conducted in this study (BMEI0747, I1305, I1367, II0098 and II0923; Table 3 and Additional File 3, Table S3) [23]. The low similarity of regulated genes from these two studies that examined a total of 3 different growth phases provides further support of the VjbR temporal gene regulation observed here [23].

A similar pattern of temporal gene regulation by AHL quorum sensing signals has also been observed in P. aeruginosa [26, 40]. Distinct regulons were identified at an exponential and early stationary growth phase by utilization of a mutated strain that does not produce AHL signals, leading to the conclusion that the temporal regulation is independent of AHL concentration [26, 40]. Examination of two luxR gene transcript levels in P. aeruginosa revealed an increase from the late logarithmic to early stationary phase, coinciding with the induction of most quorum-activated genes and supporting a hypothesis that the receptor levels govern the onset of induction [40]. Likewise, the relative expression of B. melitensis vjbR was found to increase 25-fold from exponential to stationary growth phase by qRT-PCR (Fig. 4). The observed increase in the transcript levels of vjbR supports a similar hypothesis for the temporal gene regulation observed by VjbR in B. melitensis

Relative expression of vjbR transcript over time. Taqman real-time RT-PCR of vjbR in B. melitensis 16M expressed as the mean relative concentration (to 16srRNA) from 3 biological replicates ± standard deviation. Filled blue squares represent the relative expression of vjbR and the open light blue squares represent the OD600 of corresponding cultures. The exponential growth stage for microarray analysis corresponds to OD600 = 0.4 (14 hrs) and the stationary growth phase corresponds to OD600 = 1.5 (28 hrs).

VjbR and C12-HSL alter expression of a common set of genes

To examine the relationship between VjbR and C12-HSL gene regulation, the significantly altered genes from the VjbR regulon were compared to the significantly altered genes from the C12-HSL regulon (Tables 2,3,4 and Additional File 3, Table S3). In all, 72 genes were found to be co-regulated during the exponential growth phase and 55 genes at the stationary growth phase, representing approximately 20% of the total number of altered genes identified by microarray analysis. The majority of the common, differently expressed transcripts (124 out of 127) were found to be altered in the same direction by both the vjbR mutant and in response to C12-HSL administration, implying that VjbR and C12-HSL exert inverse effects on gene expression.

In addition to the T4SS and flagella operons being inversely co-regulated, T4SS-dependent effector proteins VceA and VceC were also found to be inversely regulated by the vjbR deletion mutant and addition of C12-HSL to wildtype cells, as well as exopolysaccharide production, proteases, peptidases and a universal stress protein (Table 4). Flagellar and exopolysaccharide synthesis genes have been implicated in the intracellular survival of Brucella in mice and macrophages [4, 41]. The down-regulation of these factors in vjbR mutants and in response to C12-HSL suggests that VjbR promotes Brucella virulence; while conversely, C12-HSL represses such gene expression, either through the same regulatory pathway or independently.

These results expand on earlier findings that C12-HSL represses transcription of the T4SS through interactions with the response domain of VjbR [17, 42]. The genes identified as co-regulated between VjbR and C12-HSL may be the result of C12-HSL reducing VjbR transcriptional activity through the AHL binding domain. Additionally, the observation that the expression of vjbR itself was down-regulated at the stationary growth phase in response to C12-HSL administration further supports a non-cooperative relationship between VjbR and C12-HSL, (2.9-fold by qRT-PCR and 1.2-fold by microarray analysis, Table 1).

Physiological characterization of VjbR and C12-HSL transcriptomes

Virulence. Microarray results confirmed alteration of the previously identified T4SS and flagellar genes, both virulence-associated operons found to be regulated by VjbR and/or C12-HSL, as well as genes with homology to the recently identified T4SS effector proteins in B. abortus and B. suis [14, 27]. Furthermore, many putative virulence factors not previously correlated with VjbR or C12-HSL regulation in Brucella spp. were identified; including protein secretion factors, adhesins, lipoproteins, proteases, outer membrane proteins, antibiotic and toxin resistance genes, stress survival genes and genes containing tetratricopeptide repeats (Tables 2,3,4 and Additional File 3, Table S3). Many of these gene products have been found to be associated with virulence and infection in numerous other bacterial pathogens have not been studied in Brucella spp., calling for further investigation and characterization.

A BLAST search of the T4SS effector protein VceA against B. melitensis 16M revealed two genes with high and low degrees of similarity, BMEI0390 and BMEII1013, with 98.8% and 35% (respectively) amino acid similarity. VceA (BMEI0390) was found to be down-regulated at the exponential growth phase by the vjbR deletion mutant and the addition of C12-HSL (1.4-fold and 1.3 fold) but was not statistically significant nor met the cut-off value of 1.5-fold (Table 4). Additionally, a BLAST search of VceC revealed a gene with 99% amino acid similarity, BMEI0948, which was found to be up-regulated by ΔvjbR and treatment of C12-HSL in wildtype cells at the stationary growth phase (1.6 and 1.3-fold, respectively, Table 4). The vceC homologue, which is located downstream of a confirmed VjbR promoter sequence, was unexpectedly found to be down-regulated by VjbR and not up-regulated along with the T4SS (virB operon) [27]. Expression of vceA was found to be promoted at the exponential growth phase by VjbR, however, no information was obtained at the stationary growth phase for comparison to virB in this global survey.

Deletion of vjbR resulted in the down-regulation of a gene locus that encodes for the ATP-binding protein associated with the cyclic β-(1,2) glucan export apparatus (BMEI0984, 2.1-fold) and an exopolysaccharide export gene exoF (BMEII0851, 2.1-fold) at the exponential growth phase; while the treatment of C12-HSL in the ΔvjbR null background up-regulated these same genes 1.7 and 2.1-fold, respectively, (Table 3). Additionally, C12-HSL was found to down-regulate expression of opgC (BMEI0330), responsible for substitutions to cyclic β-(1,2) glucan, 2.0 and 1.9-fold at the exponential growth phase in the wildtype and ΔvjbR backgrounds (respectively, Table 4) [43]. Cyclic β-(1,2) glucan is crucial for the intracellular trafficking of Brucella by diverting the endosome vacuole from the endosomal pathway, thus preventing lysosomal fusion and degradation and favoring development of the brucellosome [4]. Mutations in the vjbR locus do not appear to have a profound effect on trafficking diversion from the early endosomal pathway; however, it is plausible that cyclic β-(1,2) glucan and derivatives may be important for subsequent vacuole modulation and/or brucellosome maintenance during the course of infection [14].

Deletion of vjbR resulted in alteration in the expression of three adhesins: aidA (BMEII1069, down-regulated 1.5-fold at both growth stages examined), aidA-1 (BMEII1070, up-regulated 1.7-fold) at the exponential growth phase, and a gene coding for a cell surface protein (BMEI1873, down-regulated 2.2-fold) at the exponential growth phase (Table 4). Adhesins can serve as potent biological effectors of inflammation, apoptosis and cell recognition, potentially contributing to the virulence and intracellular survival of Brucella spp. [44–46]. For instance, AidA adhesins are important for Bordetella pertussis recognition of host cells and in discriminating between macrophages and ciliated epithelial cells in humans [45].

Transporters. A large number of genes encoding transporters (90 total) were altered in ΔvjbR or in response to the addition of C12-HSL to wildtype cultures (Table 3 and Additional File 3, Table S3). For example, an exporter of O-antigen (BMEII0838) was identified to be down-regulated 2.0-fold by the deletion of vjbR at an exponential growth phase, and 4.3 and 1.7-fold by the addition of C12-HSL to wildtype cells at exponential and stationary growth phases, respectively (Table 3). Among the differently expressed transporters, ABC-type transporters were most highly represented, accounting for 62 out of the 90 transporter genes (including 15 amino acid transporters, 10 carbohydrate transporters and 16 transporters associated with virulence and/or defense mechanisms) (Table 3 and Additional File 3, Table S3). The correlation between ABC transporters and the ability to adapt to different environments is in tune with the ability of Brucella spp. to survive in both extracellular and intracellular environments [47].

Transcription. Based on microarray analysis results, vjbR deletion or the addition of C12-HSL to wildtype cells altered the expression of 42 transcriptional regulators, comprised of 12 families and 14 two-component response regulators or signal transducing mechanisms (Table 2 and Additional File 3, Table S3). Among the transcriptional families altered by ΔvjbR and/or the addition of C12-HSL, 9 families (LysR, TetR, IclR, AraC, DeoR, GntR, ArsR, MarR and Crp) have been implicated in the regulation of virulence genes in a number of other pathogenic organisms [35, 48–55]. The regulation of virB has been reported to be influenced not only by the deletion of vjbR and C12-HSL treatment, but by several additional factors including integration host factor (IHF), BlxR, a stringent response mediator Rsh, HutC, and AraC (BMEII1098) [14, 15, 56–58]. The same AraC transcriptional regulator was found to altered by vjbR deletion and C12-HSL treatment of wildtype cells: down-regulated 1.8 and 2.8-fold at exponential phase (respectively), and up-regulated 1.9 and 1.5-fold (respectively) at the stationary growth phase (Table 2). Additionally, HutC (BMEII0370) was also found to be down-regulated at the exponential growth phase by the ΔvjbR mutant (1.8-fold), suggesting several levels of regulation for the virB operon by the putative QS components in B. melitensis (Additional File 3, Table S3).

In addition to transcriptional regulators linked to virulence, microarray analyses also revealed two differentially expressed transcriptional regulators that contain the LuxR HTH DNA binding pfam domain (gerE, pfam00196). Gene transcript BMEII0051 was found to be down-regulated 1.9 and 2.8-fold in response to a vjbR deletion and addition of C12-HSL to wildtype cells (respectively) at an exponential growth phase (Table 2). This luxR-like gene is located downstream of a VjbR consensus promoter sequence and thus most likely directly promoted by VjbR [27]. The second luxR-like gene, BMEI1607, was up-regulated 1.8-fold and 3.0-fold in the vjbR mutant and in response to exogenous C12-HSL at the exponential growth phase (respectively), and down-regulated 1.5-fold by the deletion of vjbR at the stationary growth phase (Table 2). This gene locus was not found to be located downstream of a predicted VjbR promoter sequence and may or may not be directly regulated by VjbR. Additionally, blxR was found to be induced 27.5-fold in wildtype cells treated with C12-HSL at the stationary growth phase by qRT-PCR (Table 1). Likewise, qRT-PCR verified a 2.9-fold down-regulation of vjbR in wildtype cells supplied with exogenous C12-HSL at the stationary growth phase. The identification and alteration of genes containing the HTH LuxR DNA binding domain by ΔvjbR and C12-HSL administration, particularly one located downstream of the VjbR consensus promoter sequence, is of great interest. These observations potentially suggest a hierarchical arrangement of multiple transcriptional circuits which may or may not function in a QS manner, as observed in organisms such as P. aeruginosa [26].

AHL synthesis. The deletion of vjbR or addition of C12-HSL resulted in alteration in the expression of 15 candidate AHL synthesis genes, based on the gene product's potential to interact with the known metabolic precursors of AHLs, S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) and acylated acyl carrier protein (acyl-ACP) (Additional File 2, Table S2) [59]. An E. coli expression system was utilized because B. melitensis has been shown to produce an AiiD-like lactonase capable of inactivating C12-HSL [60]. Cross streaks with E. coli AHL sensor strains and clones expressing candidate AHL synthesis genes failed to induce the sensor stains, while positive control E. coli clones expressing rhlI and lasI from P. aeruginosa and exogenous 3-oxo-C12-HSL did in fact induce the sensor strains (data not shown) [61].

C12-HSL regulates gene expression independent of VjbR

In addition to the investigation on the influences of a vjbR deletion or addition of C12-HSL to wildtype bacteria on gene expression, treatment of ΔvjbR with exogenous C12-HSL was also assessed by microarray analyses. Compared to untreated wildtype cells, 87% fewer genes were identified as differentially altered in response to C12-HSL in the vjbR null background as opposed to wildtype cells administered C12-HSL. In the absence of VjbR, exogenous C12-HSL altered the expression of 82 genes; 34 at the exponential growth phase and 48 genes at the stationary growth phase (Fig. 2, red circles and Additional File 5, Table S5). Of these 82 statistically significant altered transcripts, only 4 were commonly altered with the same magnitude by a deletion of vjbR or wildtype cells treated with C12-HSL (Fig. 2). At the exponential growth phase, administration of C12-HSL exerted an equal effect on gene expression, up and down-regulating 19 and 23 genes (respectively, Fig. 2). On the contrary, at the stationary phase all 48 genes were up-regulated, a dramatically different profile than the down-regulation observed for the majority of differently expressed genes in C12-HSL treated wildtype cells (Fig. 2). Collectively, this data supports that C12-HSL is capable of influencing gene expression independent of VjbR.

There is evidence that C12-HSL may interact with a second LuxR homologue, BlxR [18]. Induction of blxR expression in response to C12-HSL was highly variable by microarray analysis; however, qRT-PCR revealed that blxR was up-regulated 99.5-fold in bacteria lacking vjbR treated with C12-HSL, compared to 27.5-fold in wildtype cells that were administered C12-HSL at the stationary growth phase. One possible explanation for this observation is that VjbR inhibits the induction of blxR by binding the AHL substrate and therefore lowering the cellular concentration of available C12-HSL for blxR induction, but has not been demonstrated.

Interestingly, 58% of the gene transcripts found to be altered in an recent study of the function of ΔblxR were also found to be altered by the addition of C12-HSL in the ΔvjbR background, and increased to 88% if we lowered the threshold from our 1.5-fold cutoff (Additional File 5, Table S5) [15]. A second study that similarly examined the transcript and proteomic alterations due to a deletion in babR corresponded with 6 genes identified in our study: with 2 genes found to be unique to the addition of C12-HSL in the ΔvjbR background (BMEI0231 and I1638, Additional File 5, Table S5), and 4 genes additionally altered by the deletion of vjbR or addition of C12-HSL in the wildtype background (BMEI0451, I0712, I1196 and II0358, Additional File 3, Table S3) [23]. Although many of these genes were not statistically significant in our analyses, this is a strikingly high correlation since the same conditions were not examined (ΔblxR vs. wt compared to ΔvjbR vs. ΔvjbR + C12-HSL), as well as the use of differing microarray platforms and analyses procedures. This connection may suggest that the genes altered by the presence of C12-HSL in the absence of VjbR may be due to C12-HSL activation of BlxR.

Conclusions

The goal of this work was to provide an elementary understanding in the role of the putative QS components in the virulence and survival of B. melitensis. VjbR is a homologue of LuxR, a transcriptional regulator previously shown to interact with an AHL signal C12-HSL and modulate expression of transcripts required for intracellular survival [14, 17]. Custom B. melitensis microarrays were utilized to examine the regulons controlled by VjbR and C12-HSL, revealing a large number of genes potentially involved in the virulence and intracellular survival of the organism. Such genes include adhesins, proteases, lipoproteins, a hemolysin, secretion system components and effector proteins, as well as metabolic genes involved in energy production, amino acid, carbohydrate, and lipid metabolism. Furthermore, deletion of vjbR and C12-HSL treatment altered the expression of genes coding for components involved in the transport of numerous substrates across the cell membrane.

The microarray analyses conducted in this study also confirmed previous findings that fliF and the virB operon are regulated by ΔvjbR and exogenous C12-HSL treatment at an exponential growth phase and stationary growth phase (respectively), as well as the potential effector proteins VceA and VceC, validating the microarray approach to identify additional genes regulated by these putative QS components [14, 27]. The contribution of VjbR gene regulation at different growth phases in not fully understood, but microarray analyses suggests that there are distinct sets of genes regulated at both growth phases in addition to the flagellar and T4SS operons. Previous studies examining the effect of timing on QS related genes in P. aeruginosa hypothesized that the transcriptional regulator and not the inducing or repressing signal is responsible for the continuum of responses observed [40]. Such a hypothesis is supported by the observed increase of vjbR expression over time in B. melitensis.

Deletion of vjbR and treatment of C12-HSL both resulted in a global modulation of gene expression. Examination of the relationship in respect to the genes commonly altered between ΔvjbR and wildtype bacteria administered C12-HSL suggests that C12-HSL reduces VjbR activity, based upon the following observations: 1) An inverse correlation in gene expression for all but three genes found to be altered by VjbR and C12-HSL, 2) Addition of exogenous C12-HSL to growth media mimics the deletion of VjbR in respect to gene alteration, 3) In the absence of vjbR, C12-HSL treatment has a markedly different effect on gene expression at the stationary growth phase, found to only promote gene expression, and 4) virB repression in response to the addition of C12-HSL is alleviated by deletion of the response receiver domain of VjbR [17]. The observed promotion of gene expression with the treatment of C12-HSL in a ΔvjbR background could potentially be occurring through a second LuxR-like protein BlxR, supported by the high correlation of commonly altered genes by ΔblxR and ΔvjbR with the addition of C12-HSL in independent studies [15, 23]. Often, the LuxR transcriptional regulator and AHL signal form a positive feedback loop, increasing the expression of luxR and the AHL synthesis gene [62]. The observed up-regulation of blxR by C12-HSL may be an example of such a feedback loop, further supporting an activating role C12-HSL and BlxR activity.

Although evidence is indirect, these observations suggest that there may be two dueling transcriptional circuits with the LuxR transcriptional regulators (VjbR and BlxR). C12-HSL may provide a level of regulation between the two systems, deactivating VjbR and potentially activating BlxR activity during the transition to stationary phase. It appears that C12-HSL reduces VjbR activity, alters expression of 2 additional transcriptional regulators that contain the LuxR DNA binding domain, induces expression of BlxR and potentially activates gene expression through interactions with BlxR. It would be interesting to determine if the decrease in virB expression observed in wildtype cells at stationary phase is a result of C12-HSL accumulation and subsequent "switching" of transcriptional circuits in vitro [63]. Further experiments are needed to fully understand the temporal regulation of VjbR and associations with C12HSL, as well as indentification of AHL synthesis gene(s) in Brucella spp.

The role of the LuxR transcriptional regulators VjbR and BlxR and the AHL signal in relation to quorum sensing has not been fully deduced. Continuing investigation of these putative QS components in vitro and in vivo will help determine if these components work in a QS-dependent manner in the host cell or if they function more in a diffusion or spatial sensing context to allow differentiation between intracellular and extracellular environments [64]. Future experiments that elucidate how these processes contribute to the "stealthiness" of Brucellae and will provide additional clues to the intracellular lifestyle of this particular bacterium.

References

Chaves-Olarte E, Guzman-Verri C, Meresse S, Desjardins M, Pizarro-Cerda J, Badilla J, Gorvel JP: Activation of Rho and Rab GTPases dissociates Brucella abortus internalization from intracellular trafficking. Cell Microbiol. 2002, 4 (10): 663-676. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00221.x.

Gross A, Terraza A, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Liautard JP, Dornand J: In vitro Brucella suis infection prevents the programmed cell death of human monocytic cells. Infect Immun. 2000, 68 (1): 342-351. 10.1128/IAI.68.1.342-351.2000.

Pizarro-Cerda J, Meresse S, Parton RG, van der Goot G, Sola-Landa A, Lopez-Goni I, Moreno E, Gorvel JP: Brucella abortus transits through the autophagic pathway and replicates in the endoplasmic reticulum of nonprofessional phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1998, 66 (12): 5711-5724.

Arellano-Reynoso B, Lapaque N, Salcedo S, Briones G, Ciocchini AE, Ugalde R, Moreno E, Moriyon I, Gorvel JP: Cyclic beta-1,2-glucan is a Brucella virulence factor required for intracellular survival. Nat Immunol. 2005, 6 (6): 618-625. 10.1038/ni1202.

Celli J, de Chastellier C, Franchini DM, Pizarro-Cerda J, Moreno E, Gorvel JP: Brucella evades macrophage killing via VirB-dependent sustained interactions with the endoplasmic reticulum. J Exp Med. 2003, 198 (4): 545-556. 10.1084/jem.20030088.

Godfroid F, Taminiau B, Danese I, Denoel P, Tibor A, Weynants V, Cloeckaert A, Godfroid J, Letesson JJ: Identification of the perosamine synthetase gene of Brucella melitensis 16M and involvement of lipopolysaccharide O side chain in Brucella survival in mice and in macrophages. Infect Immun. 1998, 66 (11): 5485-5493.

Anand SK, Griffiths MW: Quorum sensing and expression of virulence in Escherichia coli O157:H7. Int J Food Microbiol. 2003, 85 (1-2): 1-9. 10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00482-8.

Davies DG, Parsek MR, Pearson JP, Iglewski BH, Costerton JW, Greenberg EP: The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science. 1998, 280 (5361): 295-298. 10.1126/science.280.5361.295.

Fuqua C, Parsek MR, Greenberg EP: Regulation of gene expression by cell-to-cell communication: acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing. Annu Rev Genet. 2001, 35: 439-468. 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090913.

Withers HL, Nordstrom K: Quorum-sensing acts at initiation of chromosomal replication in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998, 95 (26): 15694-15699. 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15694.

Birck C, Malfois M, Svergun D: Insights into signal transduction revealed by the low resolution structure of the FixJ response regulator. J Mol Biol. 2002, 321 (3): 447-457. 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00651-4.

Ducros VM, Lewis RJ, Verma CS, Dodson EJ, Leonard G, Turkenburg JP, Murshudov GN, Wilkinson AJ, Brannigan JA: Crystal structure of GerE, the ultimate transcriptional regulator of spore formation in Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 2001, 306 (4): 759-771. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4443.

Schlegel A, Bohm A, Lee SJ, Peist R, Decker K, Boos W: Network regulation of the Escherichia coli maltose system. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002, 4 (3): 301-307.

Delrue RM, Deschamps C, Leonard S, Nijskens C, Danese I, Schaus JM, Bonnot S, Ferooz J, Tibor A, De Bolle X: A quorum-sensing regulator controls expression of both the type IV secretion system and the flagellar apparatus of Brucella melitensis. Cell Microbiol. 2005, 7 (8): 1151-1161. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00543.x.

Rambow-Larsen AA, Rajashekara G, Petersen E, Splitter G: Putative quorum-sensing regulator BlxR of Brucella melitensis regulates virulence factors including the type IV secretion system and flagella. J Bacteriol. 2008, 190 (9): 3274-3282. 10.1128/JB.01915-07.

Taminiau B, Daykin M, Swift S, Boschiroli ML, Tibor A, Lestrate P, De Bolle X, O'Callaghan D, Williams P, Letesson JJ: Identification of a quorum-sensing signal molecule in the facultative intracellular pathogen Brucella melitensis. Infect Immun. 2002, 70 (6): 3004-3011. 10.1128/IAI.70.6.3004-3011.2002.

Letesson JJ, Delrue R, Bonnot S, Deschamps C, Leonard S, De Bolle X: The quorum-sensing related transcriptional regulator Vjbr controls expression of the type IV secretion and flagellar genes in Brucella melitensis 16M. Proceedings of the 57th Annual Brucellosis Research Conference 13-14 November 2004; Chicago, IL. 2004, 16-17.

Letesson JJ, De Bolle X: Brucella Virulence:A matter of control. Brucella: Molecular and Cellular Biology. Edited by: López-Goñi I, Moriyon I. 2004, Norfolk: Horizon Biosciences, 144-

Kahl-McDonagh MM, Ficht TA: Evaluation of protection afforded by Brucella abortus and Brucella melitensis unmarked deletion mutants exhibiting different rates of clearance in BALB/c mice. Infect Immun. 2006, 74 (7): 4048-4057. 10.1128/IAI.01787-05.

Rhodius V: Purification of RNA from E. coli. DNA Microarrays. Edited by: Bowtell D, Sambrook J. 2002, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 149-152. 2

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD: Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001, 25 (4): 402-408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262.

Delrue RM, Lestrate P, Tibor A, Letesson JJ, De Bolle X: Brucella pathogenesis, genes identified from random large-scale screens. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004, 231 (1): 1-12. 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00963-7.

Uzureau S, Lemaire J, Delaive E, Dieu M, Gaigneaux A, Raes M, De Bolle X, Letesson JJ: Global analysis of Quorum Sensing targets in the intracellular pathogen Brucella melitensis 16M. J Proteome Res. 2010,

Freeman JA, Bassler BL: A genetic analysis of the function of LuxO, a two-component response regulator involved in quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi. Mol Microbiol. 1999, 31 (2): 665-677. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01208.x.

Freeman JA, Bassler BL: Sequence and function of LuxU: a two-component phosphorelay protein that regulates quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi. J Bacteriol. 1999, 181 (3): 899-906.

Wagner VE, Bushnell D, Passador L, Brooks AI, Iglewski BH: Microarray analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing regulons: effects of growth phase and environment. J Bacteriol. 2003, 185 (7): 2080-2095. 10.1128/JB.185.7.2080-2095.2003.

de Jong MF, Sun YH, den Hartigh AB, van Dijl JM, Tsolis RM: Identification of VceA and VceC, two members of the VjbR regulon that are translocated into macrophages by the Brucella type IV secretion system. Mol Microbiol. 2008, 70 (6): 1378-1396. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06487.x.

Kohler S, Foulongne V, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Bourg G, Teyssier J, Ramuz M, Liautard JP: The analysis of the intramacrophagic virulome of Brucella suis deciphers the environment encountered by the pathogen inside the macrophage host cell. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002, 99 (24): 15711-15716. 10.1073/pnas.232454299.

Hong PC, Tsolis RM, Ficht TA: Identification of genes required for chronic persistence of Brucella abortus in mice. Infect Immun. 2000, 68 (7): 4102-4107. 10.1128/IAI.68.7.4102-4107.2000.

Kim S, Watarai M, Kondo Y, Erdenebaatar J, Makino S, Shirahata T: Isolation and characterization of mini-Tn5Km2 insertion mutants of Brucella abortus deficient in internalization and intracellular growth in HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 2003, 71 (6): 3020-3027. 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3020-3027.2003.

Wu Q, Pei J, Turse C, Ficht TA: Mariner mutagenesis of Brucella melitensis reveals genes with previously uncharacterized roles in virulence and survival. BMC Microbiol. 2006, 6: 102-10.1186/1471-2180-6-102.

Zygmunt MS, Hagius SD, Walker JV, Elzer PH: Identification of Brucella melitensis 16M genes required for bacterial survival in the caprine host. Microbes Infect. 2006, 8 (14-15): 2849-2854. 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.09.002.

Lestrate P, Delrue RM, Danese I, Didembourg C, Taminiau B, Mertens P, De Bolle X, Tibor A, Tang CM, Letesson JJ: Identification and characterization of in vivo attenuated mutants of Brucella melitensis. Mol Microbiol. 2000, 38 (3): 543-551. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02150.x.

Lestrate P, Dricot A, Delrue RM, Lambert C, Martinelli V, De Bolle X, Letesson JJ, Tibor A: Attenuated signature-tagged mutagenesis mutants of Brucella melitensis identified during the acute phase of infection in mice. Infect Immun. 2003, 71 (12): 7053-7060. 10.1128/IAI.71.12.7053-7060.2003.

Haine V, Sinon A, Van Steen F, Rousseau S, Dozot M, Lestrate P, Lambert C, Letesson JJ, De Bolle X: Systematic targeted mutagenesis of Brucella melitensis 16M reveals a major role for GntR regulators in the control of virulence. Infect Immun. 2005, 73 (9): 5578-5586. 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5578-5586.2005.

Foulongne V, Bourg G, Cazevieille C, Michaux-Charachon S, O'Callaghan D: Identification of Brucella suis genes affecting intracellular survival in an in vitro human macrophage infection model by signature-tagged transposon mutagenesis. Infect Immun. 2000, 68 (3): 1297-1303. 10.1128/IAI.68.3.1297-1303.2000.

Eskra L, Canavessi A, Carey M, Splitter G: Brucella abortus genes identified following constitutive growth and macrophage infection. Infect Immun. 2001, 69 (12): 7736-7742. 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7736-7742.2001.

Allen CA, Adams LG, Ficht TA: Transposon-derived Brucella abortus rough mutants are attenuated and exhibit reduced intracellular survival. Infect Immun. 1998, 66 (3): 1008-1016.

LeVier K, Phillips RW, Grippe VK, Roop RM, Walker GC: Similar requirements of a plant symbiont and a mammalian pathogen for prolonged intracellular survival. Science (New York, NY. 2000, 287 (5462): 2492-2493.

Schuster M, Lostroh CP, Ogi T, Greenberg EP: Identification, timing, and signal specificity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-controlled genes: a transcriptome analysis. J Bacteriol. 2003, 185 (7): 2066-2079. 10.1128/JB.185.7.2066-2079.2003.

Leonard S, Ferooz J, Haine V, Danese I, Fretin D, Tibor A, de Walque S, De Bolle X, Letesson JJ: FtcR is a new master regulator of the flagellar system of Brucella melitensis 16M with homologs in Rhizobiaceae. J Bacteriol. 2006

Uzureau S, Godefroid M, Deschamps C, Lemaire J, De Bolle X, Letesson JJ: Mutations of the quorum sensing-dependent regulator VjbR lead to drastic surface modifications in Brucella melitensis. J Bacteriol. 2007, 189 (16): 6035-6047. 10.1128/JB.00265-07.

Roset MS, Ciocchini AE, Ugalde RA, de Iannino Inon N: The Brucella abortus cyclic beta-1,2-glucan virulence factor is substituted with O-ester-linked succinyl residues. J Bacteriol. 2006, 188 (14): 5003-5013. 10.1128/JB.00086-06.

Abramson T, Kedem H, Relman DA: Proinflammatory and proapoptotic activities associated with Bordetella pertussis filamentous hemagglutinin. Infect Immun. 2001, 69 (4): 2650-2658. 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2650-2658.2001.

Hoepelman AI, Tuomanen EI: Consequences of microbial attachment: directing host cell functions with adhesins. Infect Immun. 1992, 60 (5): 1729-1733.

McGuirk P, Mills KH: Direct anti-inflammatory effect of a bacterial virulence factor: IL-10-dependent suppression of IL-12 production by filamentous hemagglutinin from Bordetella pertussis. Eur J Immunol. 2000, 30 (2): 415-422. 10.1002/1521-4141(200002)30:2<415::AID-IMMU415>3.0.CO;2-X.

Garmory HS, Titball RW: ATP-binding cassette transporters are targets for the development of antibacterial vaccines and therapies. Infect Immun. 2004, 72 (12): 6757-6763. 10.1128/IAI.72.12.6757-6763.2004.

Harris SJ, Shih YL, Bentley SD, Salmond GP: The hexA gene of Erwinia carotovora encodes a LysR homologue and regulates motility and the expression of multiple virulence determinants. Mol Microbiol. 1998, 28 (4): 705-717. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00825.x.

Ramos JL, Martinez-Bueno M, Molina-Henares AJ, Teran W, Watanabe K, Zhang X, Gallegos MT, Brennan R, Tobes R: The TetR family of transcriptional repressors. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005, 69 (2): 326-356. 10.1128/MMBR.69.2.326-356.2005.

Molina-Henares AJ, Krell T, Eugenia Guazzaroni M, Segura A, Ramos JL: Members of the IclR family of bacterial transcriptional regulators function as activators and/or repressors. FEMS microbiology reviews. 2006, 30 (2): 157-186. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2005.00008.x.

Childers BM, Klose KE: Regulation of virulence in Vibrio cholerae: the ToxR regulon. Future Microbiol. 2007, 2: 335-344. 10.2217/17460913.2.3.335.

Haghjoo E, Galan JE: Identification of a transcriptional regulator that controls intracellular gene expression in Salmonella Typhi. Mol Microbiol. 2007, 64 (6): 1549-1561. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05754.x.

Cornelis G, Sluiters C, de Rouvroit CL, Michiels T: Homology between virF, the transcriptional activator of the Yersinia virulence regulon, and AraC, the Escherichia coli arabinose operon regulator. J Bacteriol. 1989, 171 (1): 254-262.

Ellison DW, Miller VL: Regulation of virulence by members of the MarR/SlyA family. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006, 9 (2): 153-159. 10.1016/j.mib.2006.02.003.

Scortti M, Monzo HJ, Lacharme-Lora L, Lewis DA, Vazquez-Boland JA: The PrfA virulence regulon. Microbes Infect. 2007, 9 (10): 1196-1207. 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.05.007.

Dozot M, Boigegrain RA, Delrue RM, Hallez R, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Danese I, Letesson JJ, De Bolle X, Kohler S: The stringent response mediator Rsh is required for Brucella melitensis and Brucella suis virulence, and for expression of the type IV secretion system virB. Cell Microbiol. 2006

Sieira R, Comerci DJ, Pietrasanta LI, Ugalde RA: Integration host factor is involved in transcriptional regulation of the Brucella abortus virB operon. Mol Microbiol. 2004, 54 (3): 808-822. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04316.x.

Sieira R, Arocena GM, Bukata L, Comerci DJ, Ugalde RA: Metabolic control of virulence genes in Brucella abortus: HutC coordinates virB expression and the histidine utilization pathway by direct binding to both promoters. J Bacteriol. 192 (1): 217-224. 10.1128/JB.01124-09.

Pappas KM, Weingart CL, Winans SC: Chemical communication in proteobacteria: biochemical and structural studies of signal synthases and receptors required for intercellular signalling. Mol Microbiol. 2004, 53 (3): 755-769. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04212.x.

Lemaire J, Uzureau S, Mirabella A, De Bolle X, Letesson JJ: Identification of a quorum quenching enzyme in the facultative intracellular pathogen Brucella melitensis 16M. Proceedings of the 60th Annual Brucellosis Research Conference: 1-2 December 2007; Chicago, IL. 2007, 31-

Lindsay A, Ahmer BM: Effect of sdiA on biosensors of N-Acylhomoserine lactones. J Bacteriol. 2005, 187 (14): 5054-5058. 10.1128/JB.187.14.5054-5058.2005.

Seed PC, Passador L, Iglewski BH: Activation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasI gene by LasR and the Pseudomonas autoinducer PAI: an autoinduction regulatory hierarchy. J Bacteriol. 1995, 177 (3): 654-659.

den Hartigh AB, Sun YH, Sondervan D, Heuvelmans N, Reinders MO, Ficht TA, Tsolis RM: Differential requirements for VirB1 and VirB2 during Brucella abortus infection. Infect Immun. 2004, 72 (9): 5143-5149. 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5143-5149.2004.

Hense BA, Kuttler C, Muller J, Rothballer M, Hartmann A, Kreft JU: Does efficiency sensing unify diffusion and quorum sensing?. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007, 5 (3): 230-239. 10.1038/nrmicro1600.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-AI48496 to T.A.F.) and Region VI Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Research (1U54AI057156-0100 to T.A.F.).J.N.W. was supported by USDA Food and Agricultural Sciences National Needs Graduate Fellowship Grant (2002-38420-5806).

We thank Tana Crumley, Dr. Carlos Rossetti, and Dr. Sarah Lawhon for all of their assistance with the microarray work, as well as the Western Regional Center of Excellence (WRCE) Pathogen Expression Core (Dr. John Lawson, Dr. Mitchell McGee, Dr. Rhonda Friedberg, and Dr. Stephen A. Johnston, A.S.U.) for developing and printing the B. melitensis cDNA microarrays.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

JNW conceived, designed and performed the experiments, and drafted the manuscript. CLG performed computational analyses and assisted in drafting the manuscript. KLD performed computational analyses, contributed to manuscript development and critically revised the manuscript. HRG helped to analyze the data and critically revised the manuscript. LGA contributed to the data acquisition and critically revised the manuscript. TAF conceived and coordinated the study and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12866_2009_1123_MOESM1_ESM.DOCX

Additional file 1: Table S1: Bacterial strains and plasmids. Details, genotypes and references for the strains and plasmids used in this study. (DOCX 59 KB)

12866_2009_1123_MOESM2_ESM.DOCX

Additional file 2: Table S2: PCR and Quantitative Real-Time PCR primers and probes. Provides the sequences and linkers (if applicable) of all primers used for cloning, and the qRT-PCR probes and primers used in this study. (DOCX 54 KB)

12866_2009_1123_MOESM3_ESM.DOCX

Additional file 3: Table S3: Additional genetic loci identified with significant alterations in transcript levels between B. melitensis 16M and 16MΔ vjbR with and without the addition of C 12 -HSL. Gene transcripts found to be altered by comparison of wild type and ΔvjbR, both with and without the treatment of C12-HSL at an exponential and stationary growth phase. (DOCX 184 KB)

12866_2009_1123_MOESM4_ESM.DOCX

Additional file 4: Table S4: Promoter(s) sequences and potential operons of downstream genes found to be altered by the deletion of vjbR and/or treatment of C 12 -HSL. Operons that are both found to be downstream of the predicted VjbR promoter sequence and altered by comparison of wild type and ΔvjbR, both with and without the addition of C12-HSL at exponential or stationary growth phases. (DOCX 225 KB)

12866_2009_1123_MOESM5_ESM.DOCX

Additional file 5: Table S5: Genetic loci identified with significant alterations in transcript levels between B. melitensis 16MΔ vjbR and 16MΔ vjbR with the addition of C 12 -HSL. Altered gene transcripts uniquely identified by the treatment of C12-HSL to the B. melitensis 16MΔvjbR background. (DOCX 110 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Weeks, J.N., Galindo, C.L., Drake, K.L. et al. Brucella melitensis VjbR and C12-HSL regulons: contributions of the N-dodecanoyl homoserine lactone signaling molecule and LuxR homologue VjbR to gene expression. BMC Microbiol 10, 167 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-10-167

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-10-167