Abstract

Background

microRNAs (miRNAs) are small (~22 nt) non-coding RNAs that regulate cell movement, specification, and development. Expression of miRNAs is highly regulated, both spatially and temporally. Based on direct cloning, sequence conservation, and predicted secondary structures, a large number of miRNAs have been identified in higher eukaryotic genomes but whether these RNAs are simply a subset of a much larger number of noncoding RNA families is unknown. This is especially true in zebrafish where genome sequencing and annotation is not yet complete.

Results

We analyzed the zebrafish genome to identify the number and location of proven and predicted miRNAs resulting in the identification of 35 new miRNAs. We then grouped all 415 zebrafish miRNAs into families based on seed sequence identity as a means to identify possible functional redundancy. Based on genomic location and expression analysis, we also identified those miRNAs that are likely to be encoded as part of polycistronic transcripts. Lastly, as a resource, we compiled existing zebrafish miRNA expression data and, where possible, listed all experimentally proven mRNA targets.

Conclusion

Current analysis indicates the zebrafish genome encodes 415 miRNAs which can be grouped into 44 families. The largest of these families (the miR-430 family) contains 72 members largely clustered in two main locations along chromosome 4. Thus far, most zebrafish miRNAs exhibit tissue specific patterns of expression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

As the transcriptional landscapes of eukaryotic genomes are defined, it appears that overall transcription is much more prevalent than previously thought, perhaps by as much as 10-fold greater than that needed to generate mRNAs encoding the majority of protein coding genes [1]. Abundant noncoding RNAs, both short and long, have been identified but for the most part their functional significance remains unknown. Among recently discovered small RNAs, the best characterized thus far are microRNAs (miRNAs) [2, 3]. Direct cloning strategies and bioinformatic predictions based on the presence of conserved hairpin structures and sequences have suggested that animal genomes encode hundreds, perhaps thousands, of miRNAs [4–7]. Cell movement, specification, and development are regulated, in part, by miRNAs, consistent with the fact that expression of these RNAs is highly regulated in a tissue and time-specific manner. miRNAs originate from RNA Polymerase II transcripts [8] requiring processing by the RNase III-like enzyme, Drosha before nuclear export. From the large primary transcripts, Drosha releases hairpins that are ~70 nucleotides long with extensive pairing of approximately 28 base pairs in the stem [9]. Hairpin precursors are exported from the nucleus in a RAN-GTP dependent manner using Exportin 5 [10, 11]. In the cytoplasm, miRNA precursors are further processed by a second RNase III-like enzyme, Dicer, releasing mature miRNA duplexes of ~22 nucleotides [12–14]. Typically, only one strand of the duplex pairs with a target mRNA as part of a larger dynamic ribonucleoprotein complex referred to as the RNA Induced Silencing Complex (RISC). Argonuate proteins are key components of RISCs and are thought to play an important role in whether the target mRNA is subject to translational repression or cleavage followed by degradation [15].

miRNAs usually pair with sequence elements (miRNA Recognition Elements; MREs) within the 3' UTR of their target mRNAs but there have been limited examples of pairing in the 5' UTR [16]. Since miRNAs usually pair with incomplete complementarity to their targets, bioinformatic approaches to identify targets are limited and functional analysis is required to prove mRNA:miRNA interactions. Because of this challenge, only a small number of targets have been experimentally proven. Further, since each miRNA can target multiple mRNAs and a single mRNA can be targeted by multiple miRNAs, significant work remains to characterize the full range of miRNA function [17, 18].

Zebrafish have proven to be a valuable model system to investigate miRNA function and characterize miRNA:mRNA interactions. Since the creation of active miRNAs requires cleavage by Dicer, zygotic Dicer mutants and maternal zygotic Dicer mutants have helped define the role of miRNAs during development [19, 20]. Zygotic Dicer null mutants live approximately 14 days, because there is sufficient maternal Dicer mRNA deposited into the oocyte [19]. Maternal zygotic Dicer mutants exhibit more severe developmental defects and die after only 7 days [20]. Thus, the regulation of miRNA expression is critical for early zebrafish development. For example, miR-214 is required for proper muscle formation, miR-375 is needed for pancreatic islet development, and the large miR-430 family is needed for deadenylation and clearance of maternal mRNAs at the midblastula transition [21–23].

External fertilization, fast development, and ease of genetic manipulation make zebrafish a powerful system to study vertebrate development and analyze miRNAs. To facilitate this work, microarrays and in situ hybridization experiments have provided a wealth of knowledge regarding temporal and spatial expression of miRNAs during zebrafish development [13, 14, 24, 25]. Small RNA cloning coupled with bioinformatic prediction have enabled the identification of many zebrafish miRNAs but since genome sequencing and annotation is not yet complete, the exact number of miRNAs remains to be determined. Here, we have utilized existing databases and newly available genomic sequence information to identify and catalog all known and predicted zebrafish miRNAs.

Results

Zebrafish miRNAs and Genomic Locations

Currently, the microRNA registry lists 380 miRNAs in the zebrafish genome [26]. Inclusion in the Registry implies experimental validation through direct sequencing, northern blots, or microarray approaches. As the zebrafish genome is not fully sequenced and annotated, it is likely that the sum total of zebrafish miRNAs will be larger than currently contained within the miRNA Registry. We took the approach to use sequence conservation across species and prediction algorithms to identify additional zebrafish miRNAs. Such algorithms have been applied to the human, C. elegans, and pufferfish genomes to identify miRNAs by searching for conserved hairpin structures of 60–100 nucleotides containing no branches with only a few mismatches or bulges [7]. Using MiRScan, the Sanger microRNA registry, and RNAfold, we analyzed the zebrafish genome and identified 35 new zebrafish miRNAs (Table 1). First, mature miRNA sequences from mouse and human were compared to the zebrafish genome using BLAST to identify conserved sequences. The criteria for inclusion required perfect seed sequences and less than 3–4 mismatches in the 3' ends. Next, candidate zebrafish miRNAs were examined for their genomic position to determine whether they resided in conserved genes or transcripts compared to mouse and human. Sequences adjacent to candidate miRNAs were then subjected to RNAfold to identify the presence of conserved hairpin structures. Hairpin structures and sequences were then compared across human, mouse, and zebrafish using MiRscan and Clustal W to confirm the presence of conserved sequences resembling miRNAs. Such analyses resulted in the identification of 35 new potential miRNAs bringing the total to 415 when combined with previously documented miRNAs and including those cases where both strands are utilized. We also compared the new predicted miRNAs to the Takfugu rubripes (fugu) genome and found that 7 of the new miRNAs were conserved between the two genomes. Since the fugu genome is considerably smaller than the zebrafish genome and may lack a number of elements including noncoding RNAs, we focused more extensively on sequence conservation across the zebrafish, human, and mouse genomes.

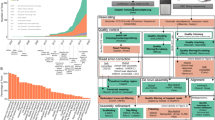

Next, we determined the chromosomal location of all miRNA genes in zebrafish. Figure 1 shows the location of miRNAs across the 25 zebrafish chromosomes. Some chromosomes are relative miRNA deserts (chromosomes 18, 21, and 25) whereas others encode large numbers of miRNAs (chromosomes 4, 5 10, 14). Strikingly, the miR-430 family contains two large clusters of 10 and 57 genes on chromosome 4 (Figure 2). Such large copy numbers are consistent with the function of the miR-430 family to target and degrade the wide variety and number of maternally deposited mRNAs coincident with zygotic transcription at the midblastula transition [22]. miRNA genes that could not yet be mapped were listed by sequencing scaffold numbers rather than chromosomal assignment and are included in Additional File 1. This table also contains current information for those miRNAs whose temporal and spatial expression patterns have been reported as well as a listing of validated mRNA targets.

Based on chromosomal location and additional genomic analysis, we were able to tabulate those miRNAs that are encoded as distinct transcripts versus those that are encoded within the introns or exons of other genes (Table 2). In mammals, approximately 50% of miRNAs are encoded within the introns of protein coding genes whereas the remainder are independently synthesized as either mono- or poly-cistronic noncoding transcripts [27–29]. For zebrafish, most miRNAs (~86%) are found in intergenic regions while only 12% exist within the introns of other genes (Table 2). We defined introns and exons only in the context of protein coding genes which may account for part of the differences between reported mammalian and zebrafish percentages. Some miRNAs are encoded within "host" genes that are split into exons and introns and therefore subject to splicing but we elected to refer to these miRNAs as independent transcripts since no proteins are apparently encoded in the host gene (for example, ENSESTG00000015836; [27]). As more genes are annotated within the zebrafish genome, some of the miRNAs we defined as intergenic may in fact reside within other RNA Polymerase II transcribed genes.

Zebrafish miRNA Transcriptional Units

Since miRNAs can originate from either mono- or poly-cistronic transcripts, we next identified zebrafish miRNAs that are closely linked in the genome and attempted to classify miRNAs as part of polycistronic transcripts based on position and expression analysis [24]. We decided to include miRNAs as part of polycistronic transcripts if the mature sequences are within 3 kb and our array data indicated similar or identical expression patterns. The decision to use 3 kb as a distance between miRNAs was arbitrary and is almost certainly an underestimate. Nevertheless, as shown in Table 3, a large number (~50%) of zebrafish miRNAs were found to reside within 3 kb of another miRNA suggesting that zebrafish miRNAs are extensively encoded within polycistronic transcripts. Recent analysis of miRNA target specificity determinants suggested that mRNAs containing multiple MREs that can be targeted by co-expressed miRNAs increases the likelihood of targeting [30]. Thus, knowing which miRNAs are transcribed as part of polycistronic transcripts will help to identify potential targets for a given miRNA.

miRNA Families

The seed region is defined as nucleotides 2–7 from the 5' end of the miRNA and is a key determinant in pairing with target mRNAs [17]. miRNAs can be grouped based on sequence identity within the seed region with the prediction that specific mRNAs can be targeted by multiple miRNAs provided these miRNAs contain identical seed sequences even if other downstream nucleotides vary. We therefore examined zebrafish miRNAs and placed those with identical seed sequences in the same family (Table 4). As above, the best example of this is the miR-430 family which is the most abundant zebrafish miRNA discovered thus far. There are 5 members of the family with over 90 copies apparently transcribed as part of 4 different RNAs. Family members bind to a common sequence found in the 3' UTR of maternal transcripts [22].

Discussion

As more and more miRNAs are identified, it has become ever more apparent that understanding global gene regulation requires identifying the targets of every miRNA and the functional consequences of such targeting. Microarrays have been used extensively to determine global miRNA expression patterns. Complementing such analyses with in situ localization of miRNAs greatly facilitates testing of candidate target genes during zebrafish development [20, 24, 25, 31]. Because of imperfect miRNA:mRNA pairing, computer algorithms to identify specific miRNA targets typically produce lists of several hundred candidate genes. Such lengthy lists can be partially refined by integrating spatial and temporal expression data for both miRNAs and their targets. Further, because many miRNAs share identical seed sequences (Table 4), it is important to identify all miRNAs that may target a given mRNA. Here, we have analyzed the existing zebrafish genome to expand the list of miRNAs to 415. We determined the chromosomal location for each miRNA and grouped them into seed sequence families. In addition, we compiled existing expression data and listed validated mRNA targets. Together, Additional File 1 provides an easy to access database that should prove valuable for those interested in understanding the role that miRNAs play in regulating gene expression.

The ease with which gain-of-function and loss-of-function experiments can be conducted in zebrafish makes it an attractive model system to study miRNA function. For loss-of-function experiments, whether in zebrafish, cultured cells, or other model organisms, it is imperative that all members of a given family be effectively knocked down to generate consistent phenotypes. By examining the data in this paper and in Additional File 1, it is possible to quickly determine functional redundancy between one or more miRNAs. Such knowledge will help to design antisense morpholino oligonucleotides when entire miRNA families need to be knocked down [21, 23].

Conclusion

Based on sequence conservation, we identified 35 new zebrafish miRNAs bringing the total number of miRNAs encoded by the zebrafish genome to 415. Bearing in mind that the zebrafish genome is not completely sequenced and annotated, analysis of the existing data suggests that the majority of miRNAs thus far evaluated are encoded as distinct, tissue specific transcripts with an even split between those contained as part of polycistronic transcripts versus those encoded as monocistronic transcripts.

Methods

To identify new zebrafish miRNAs, existing miRNA sequences from mouse were retrieved from the miRNA registry [26] and compared with the zebrafish and fugu genome using BLAST and Ensemble's Zebrafish or Fugu Genome databases [32, 33]. Predicted alignments that contained one or more mismatches within the seed region of the miRNA were discarded whereas no more than 3–4 mismatches were allowed in 3' regions. Resulting sequences were then evaluated for hairpin secondary structures using Vienna RNA Secondary Structure Prediction Program (RNAfold [34]). For those potential miRNAs exhibiting mature miRNA sequence conservation and predicted hairpin structures, MiRscan [7] and ClustalW2 [35] were utilized to compare hairpin precursor sequences to each other and to 50 previously described and highly conserved C. elegan miRNAs. Further, predicted zebrafish hairpins were examined to primarily include those located within the same transcriptional unit as their human or mouse counterpart.

Family members were determined strictly by identical seed sequences (2nd–7th nts from the 5' end). Intronic, exonic, and intergenic miRNAs were determined by location among predicted genes within Ensemble. Polycistronic family members were classified as being within 3 kb of another known or predicted miRNA and showing similar or identical expression. Zebrafish miRNA expression data was compiled from previously published sources and is included in Additional File 1[13, 14, 24, 25].

References

Birney E, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Dutta A, Guigo R, Gingeras TR, Margulies EH, Weng Z, Snyder M, Dermitzakis ET, Thurman RE, Kuehn MS, Taylor CM, Neph S, Koch CM, Asthana S, Malhotra A, Adzhubei I, Greenbaum JA, Andrews RM, Flicek P, Boyle PJ, Cao H, Carter NP, Clelland GK, Davis S, Day N, Dhami P, Dillon SC, Dorschner MO, Fiegler H, Giresi PG, Goldy J, Hawrylycz M, Haydock A, Humbert R, James KD, Johnson BE, Johnson EM, Frum TT, Rosenzweig ER, Karnani N, Lee K, Lefebvre GC, Navas PA, Neri F, Parker SC, Sabo PJ, Sandstrom R, Shafer A, Vetrie D, Weaver M, Wilcox S, Yu M, Collins FS, Dekker J, Lieb JD, Tullius TD, Crawford GE, Sunyaev S, Noble WS, Dunham I, Denoeud F, Reymond A, Kapranov P, Rozowsky J, Zheng D, Castelo R, Frankish A, Harrow J, Ghosh S, Sandelin A, Hofacker IL, Baertsch R, Keefe D, Dike S, Cheng J, Hirsch HA, Sekinger EA, Lagarde J, Abril JF, Shahab A, Flamm C, Fried C, Hackermuller J, Hertel J, Lindemeyer M, Missal K, Tanzer A, Washietl S, Korbel J, Emanuelsson O, Pedersen JS, Holroyd N, Taylor R, Swarbreck D, Matthews N, Dickson MC, Thomas DJ, Weirauch MT, Gilbert J, Drenkow J, Bell I, Zhao X, Srinivasan KG, Sung WK, Ooi HS, Chiu KP, Foissac S, Alioto T, Brent M, Pachter L, Tress ML, Valencia A, Choo SW, Choo CY, Ucla C, Manzano C, Wyss C, Cheung E, Clark TG, Brown JB, Ganesh M, Patel S, Tammana H, Chrast J, Henrichsen CN, Kai C, Kawai J, Nagalakshmi U, Wu J, Lian Z, Lian J, Newburger P, Zhang X, Bickel P, Mattick JS, Carninci P, Hayashizaki Y, Weissman S, Hubbard T, Myers RM, Rogers J, Stadler PF, Lowe TM, Wei CL, Ruan Y, Struhl K, Gerstein M, Antonarakis SE, Fu Y, Green ED, Karaoz U, Siepel A, Taylor J, Liefer LA, Wetterstrand KA, Good PJ, Feingold EA, Guyer MS, Cooper GM, Asimenos G, Dewey CN, Hou M, Nikolaev S, Montoya-Burgos JI, Loytynoja A, Whelan S, Pardi F, Massingham T, Huang H, Zhang NR, Holmes I, Mullikin JC, Ureta-Vidal A, Paten B, Seringhaus M, Church D, Rosenbloom K, Kent WJ, Stone EA, Batzoglou S, Goldman N, Hardison RC, Haussler D, Miller W, Sidow A, Trinklein ND, Zhang ZD, Barrera L, Stuart R, King DC, Ameur A, Enroth S, Bieda MC, Kim J, Bhinge AA, Jiang N, Liu J, Yao F, Vega VB, Lee CW, Ng P, Shahab A, Yang A, Moqtaderi Z, Zhu Z, Xu X, Squazzo S, Oberley MJ, Inman D, Singer MA, Richmond TA, Munn KJ, Rada-Iglesias A, Wallerman O, Komorowski J, Fowler JC, Couttet P, Bruce AW, Dovey OM, Ellis PD, Langford CF, Nix DA, Euskirchen G, Hartman S, Urban AE, Kraus P, Van Calcar S, Heintzman N, Kim TH, Wang K, Qu C, Hon G, Luna R, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG, Aldred SF, Cooper SJ, Halees A, Lin JM, Shulha HP, Zhang X, Xu M, Haidar JN, Yu Y, Ruan Y, Iyer VR, Green RD, Wadelius C, Farnham PJ, Ren B, Harte RA, Hinrichs AS, Trumbower H, Clawson H, Hillman-Jackson J, Zweig AS, Smith K, Thakkapallayil A, Barber G, Kuhn RM, Karolchik D, Armengol L, Bird CP, de Bakker PI, Kern AD, Lopez-Bigas N, Martin JD, Stranger BE, Woodroffe A, Davydov E, Dimas A, Eyras E, Hallgrimsdottir IB, Huppert J, Zody MC, Abecasis GR, Estivill X, Bouffard GG, Guan X, Hansen NF, Idol JR, Maduro VV, Maskeri B, McDowell JC, Park M, Thomas PJ, Young AC, Blakesley RW, Muzny DM, Sodergren E, Wheeler DA, Worley KC, Jiang H, Weinstock GM, Gibbs RA, Graves T, Fulton R, Mardis ER, Wilson RK, Clamp M, Cuff J, Gnerre S, Jaffe DB, Chang JL, Lindblad-Toh K, Lander ES, Koriabine M, Nefedov M, Osoegawa K, Yoshinaga Y, Zhu B, de Jong PJ: Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007, 447 (7146): 799-816. 10.1038/nature05874.

Bushati N, Cohen SM: microRNA Functions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007, 23: 175-205. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123406.

Wienholds E, Plasterk RH: MicroRNA function in animal development. FEBS Lett. 2005, 579 (26): 5911-5922. 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.070.

Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T: Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science. 2001, 294 (5543): 853-858. 10.1126/science.1064921.

Lau NC, Lim LP, Weinstein EG, Bartel DP: An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001, 294 (5543): 858-862. 10.1126/science.1065062.

Lee RC, Ambros V: An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001, 294 (5543): 862-864. 10.1126/science.1065329.

Lim LP, Glasner ME, Yekta S, Burge CB, Bartel DP: Vertebrate microRNA genes. Science. 2003, 299: 1540-10.1126/science.1080372.

Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, Yeom KH, Lee S, Baek SH, Kim VN: MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. Embo J. 2004, 23 (20): 4051-4060. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385.

Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, Lee J, Provost P, Radmark O, Kim S, Kim VN: The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003, 425 (6956): 415-419. 10.1038/nature01957.

Lund E: Nuclear export of microRNA precursors. Science. 2004, 303 (5654): 95-98. 10.1126/science.1090599.

Yi R, Qin Y, Macara IG, Cullen BR: Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes Dev. 2003, 17 (24): 3011-3016. 10.1101/gad.1158803.

Krek A, Grun D, Poy MN, Wolf R, Rosenberg L, Epstein EJ, MacMenamin P, da Piedade I, Gunsalus KC, Stoffel M, Rajewsky N: Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet. 2005, 37 (5): 495-500. 10.1038/ng1536.

Nelson PT, Baldwin DA, Scearce LM, Oberholtzer JC, Tobias JW, Mourelatos Z: Microarray-based, high-throughput gene expression profiling of microRNAs. Nat Methods. 2004, 1 (2): 155-161. 10.1038/nmeth717.

Thomson JM, Parker J, Perou CM, Hammond SM: A custom microarray platform for analysis of microRNA gene expression. Nat Methods. 2004, 1 (1): 47-53. 10.1038/nmeth704.

Peters L, Meister G: Argonaute proteins: mediators of RNA silencing. Mol Cell. 2007, 26 (5): 611-623. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.001.

Bari R, Datt Pant B, Stitt M, Scheible WR: PHO2, microRNA399, and PHR1 define a phosphate-signaling pathway in plants. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141 (3): 988-999. 10.1104/pp.106.079707.

Brennecke J, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM: Principles of MicroRNA Target Recognition. PLoS Biology. 2005, 3 (3): e85-10.1371/journal.pbio.0030085.

Lim LP, Lau NC, Garrett-Engele P, Grimson A, Schelter JM, Castle J, Bartel DP, Linsley PS, Johnson JM: Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature. 2005, 433 (7027): 769-773. 10.1038/nature03315.

Wienholds E, Koudijs MJ, van Eeden FJ, Cuppen E, Plasterk RH: The microRNA-producing enzyme Dicer1 is essential for zebrafish development. Nat Genet. 2003, 35 (3): 217-218. 10.1038/ng1251.

Giraldez AJ, Cinalli RM, Glasner ME, Enright AJ, Thomson JM, Baskerville S, Hammond SM, Bartel DP, Schier AF: MicroRNAs Regulate Brain Morphogenesis in Zebrafish. Science. 2005, 308 (5723): 833-838. 10.1126/science.1109020.

Flynt AS, Li N, Thatcher EJ, Solnica-Krezel L, Patton JG: Zebrafish miR-214 modulates Hedgehog signaling to specify muscle cell fate. Nat Genet. 2007, 39 (2): 259-263. 10.1038/ng1953.

Giraldez AJ, Mishima Y, Rihel J, Grocock RJ, Van Dongen S, Inoue K, Enright AJ, Schier AF: Zebrafish MiR-430 Promotes Deadenylation and Clearance of Maternal mRNAs. Science. 2006, 312 (5770): 75-79. 10.1126/science.1122689.

Kloosterman WP, Lagendijk AK, Ketting RF, Moulton JD, Plasterk RH: Targeted inhibition of miRNA maturation with morpholinos reveals a role for miR-375 in pancreatic islet development. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5 (8): e203-10.1371/journal.pbio.0050203.

Thatcher EJ, Flynt AS, Li N, Patton JR, Patton JG: MiRNA expression analysis during normal zebrafish development and following inhibition of the Hedgehog and Notch signaling pathways. Dev Dyn. 2007

Wienholds E, Kloosterman WP, Miska E, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Berezikov E, de Bruijn E, Horvitz HR, Kauppinen S, Plasterk RHA: MicroRNA Expression in Zebrafish Embryonic Development. Science. 2005, 309 (5732): 310-311. 10.1126/science.1114519.

Griffiths-Jones S: The microRNA Registry. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32 Database issue: D109-11. 10.1093/nar/gkh023.

Rodriguez A, Griffiths-Jones S, Ashurst JL, Bradley A: Identification of mammalian microRNA host genes and transcription units. Genome Res. 2004, 14 (10A): 1902-1910. 10.1101/gr.2722704.

Kim VN, Nam JW: Genomics of microRNA. Trends Genet. 2006, 22 (3): 165-173. 10.1016/j.tig.2006.01.003.

Kong Y, Han JH: MicroRNA: biological and computational perspective. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2005, 3 (2): 62-72.

Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Bartel DP: MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell. 2007, 27 (1): 91-105. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.017.

Weston MD, Pierce ML, Rocha-Sanchez S, Beisel KW, Soukup GA: MicroRNA gene expression in the mouse inner ear. Brain Res. 2006, 1111 (1): 95-104. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.006.

Fugu Sequencing Group at the Sanger Institute: [http://www.ensembl.org/Takifugu_rubripes/index.html]

Zebrafish Sequencing Group at the Sanger Institute: [http://www.ensembl.org/Danio_rerio/index.html]

Hofacker IL: Vienna RNA secondary structure server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31 (13): 3429-3431. 10.1093/nar/gkg599.

Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG: Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007, 23 (21): 2947-2948. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant GM 075790 to JGP and a training fellowship to EJT (GM62758).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

EJT, JB, and IP performed all experiments and analyses and created all figures. JGP designed and directed the project and JGP and EJT wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12864_2007_1446_MOESM1_ESM.xls

Additional file 1:Zebrafish miRNAs. Compilation of current zebrafish miRNA data in an excel spreadsheet. Included for each miRNA is its Registry name, genomic name, mature miRNA sequence, seed sequence, miRNA family members, expression data from two sources, chromosome #, mono- vs poly-cistronic transcripts, intron, exon or intergenic location, polycistronic transcript family members, proven targets and sense vs anti-sense. (XLS 159 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Thatcher, E.J., Bond, J., Paydar, I. et al. Genomic Organization of Zebrafish microRNAs. BMC Genomics 9, 253 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-9-253

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-9-253