Abstract

Background

Aging has been associated with widespread changes at the gene expression level in multiple mammalian tissues. We have used high density oligonucleotide arrays and novel statistical methods to identify specific transcriptional classes that may uncover biological processes that play a central role in mammalian aging.

Results

We identified 712 transcripts that are differentially expressed in young (5 month old) and old (25-month old) mouse skeletal muscle. Caloric restriction (CR) completely or partially reversed 87% of the changes in expression. Examination of individual genes revealed a transcriptional profile indicative of increased p53 activity in the older muscle. To determine whether the increase in p53 activity is associated with transcriptional activation of apoptotic targets, we performed RT-PCR on four well known mediators of p53-induced apoptosis: puma, noxa, tnfrsf10b and bok. Expression levels for these proapoptotic genes increased significantly with age (P < 0.05), while CR significantly lowered expression levels for these genes as compared to control fed old mice (P < 0.05). Age-related induction of p53-related genes was observed in multiple tissues, but was not observed in young SOD2+/- and GPX4+/- mice, suggesting that oxidative stress does not induce the expression of these genes. Western blot analysis confirmed that protein levels for both p21 and GADD45a, two established transcriptional targets of p53, were higher in the older muscle tissue.

Conclusion

These observations support a role for p53-mediated transcriptional program in mammalian aging and suggest that mechanisms other than reactive oxygen species are involved in the age-related transcriptional activation of p53 targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Aging in skeletal muscle is characterized by loss of motor neurons, variations in size and type of muscle fibers, infiltration of fat and connective tissue, and a overall decrease in muscle mass (sarcopenia) [1]. Sarcopenia, the leading cause of frailty and disability in the elderly, has also been linked to other age-associated pathology, such as osteoporosis and impaired thermoregulation [2–5]. Several biological processes, such as an increase in inflammatory cytokines and a decrease in sex and growth hormones with age [6–8], have been suggested as contributing factors to the aging of skeletal muscle. At the cellular level, older muscle is associated with decreased protein synthesis [9], an increase in DNA, protein and lipid oxidation [10, 11], and the accumulation of mitochondrial abnormalities [12].

Several studies have employed microarray technology to uncover changes in gene expression that accompany aging in skeletal muscle of mice [13], rats [14], monkeys [15] and humans [16, 17]. When taken as a whole, results obtained from these studies suggest that the expression of genes indicative of cellular damage, such as those involved in the stress or inflammatory response, increase with age, while expression of metabolic and biosynthetic genes decrease with aging. We had previously investigated age-related changes in gene expression of mouse gastrocnemius tissue using high density oligonucleotide arrays [13], but our study was limited by low sample number (3 mice per age group), an arbitrary fold change criteria (> 1.5 fold difference) with no statistical analysis to determine differentially expressed genes, and a limited survey of genes expressed in the mouse genome (6347 transcripts). We therefore decided to expand our initial investigation using a larger sample size (5 mice per age group), a stringent statistical criteria to determine differentially expressed genes [posterior probability (PP) > 0.90], and a greater representation of the mouse genome (22,690 transcripts). Our current microarray study of young and old C57BL/6NHsd mice supports previous findings on specific transcript classes differentially expressed with aging and also suggests that increased p53 activity in skeletal muscle of older animals may contribute to aging phenotypes. Caloric restriction, which extends the life span of this strain of mice by approximately 40%, prevents the majority of the changes in gene expression observed in the older mice under the control diet.

Results

General

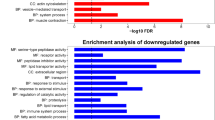

We used an empirical Bayes (EB) hierarchical modeling approach called EBarrays to identify 712 genes differentially expressed [posterior probability (PP) > .90] in old mouse gastrocnemius tissue [see additional file 1]. There are a number of advantages to our statistical approach. The main ones are the ability to combine information across genes and the dual nature of posterior probabilities. The posterior probabilities quantify evidence in favor of differential expression; however, unlike classic p-values, they can also be used to measure evidence in favor of equivalent expression. Measurements taken from gastrocnemius tissue from a group of old mice on caloric restriction (CR, n = 5), a regimen previously shown to increase lifespan and retard aging parameters in mice, was used as a negative control to aging. There were 311 genes with higher expression in the young animals and 401 genes with greater expression in the old. As expected, CR completely or partially reversed 87% of the genes with age-associated changes in expression (partial CR reversal was determined as > 25% CR effect). In agreement with previous microarray studies done on skeletal muscle of mice, monkeys and humans, we also found that genes associated with metabolic functions, particularly energy pathways, were higher in young control animals (Table 1). In contrast, genes indicative of cellular damage, such as stress response and apoptotic genes, had higher expression levels in the muscle tissue of older animals (Table 1).

Among the biological classes of transcripts with an age effect, there were several gene families whose mRNA levels were significantly increased or decreased with age [see additional file 1]. There were 8 procollagen genes (11 probe sets) that were altered with aging; 7 of these showed higher levels in the young muscle (col1a1, col1a2, col3a1, col5a1, col6a1, col6a2, col6a3) while only one procollagen gene was increased with aging (col17a1). The keratins, important cytoskeletal structural proteins, were represented by 8 genes (9 probe sets) all of which displayed increased transcript levels in older muscle. Three members (alpha, beta and delta) of the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (CEBP) family of transcription factors had increased levels of transcripts in the older mice. The encoded CEBP alpha, beta and delta proteins are important in the regulation of genes involved in immune and inflammatory responses, cell cycle arrest and body weight homeostasis (for a review, see [18]). Because many genes are represented more than once on the MOE430A Affymetrix microarray, several genes had multiple hits on our list of genes with an age effect in skeletal muscle. Among those genes with four or more independent listings were: fibromodulin (6 probe sets, all with reduced expression in the old), transferrin receptor (5 probe sets, all with reduced expression in the old), immunoglobulin kappa chain variable 8 (4 probe sets, all with increased expression in the old), and myristoylated alanine rich protein kinase C substrate (marcks) (4 probe sets, all with reduced expression in the old).

Transcript and Protein Levels of p53-Related Genes Altered with Aging

Given that skeletal muscle is largely a post-mitotic tissue, we were surprised to find that a large number of genes involved in the regulation of the cell cycle had increased mRNA levels with age (5.2% of all genes with a statistically significant effect). Two gene products that are known to play a critical role in initiating cell cycle arrest following DNA damage, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (p21) and growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible, alpha (GADD45a), were both increased significantly in the skeletal muscle of the aged mice. Expression levels for p21 and GADD45a were 1.9 and 1.8 fold higher respectively in older mouse compared to the younger animals. An age-related increase in p21 has previously been observed in muscle of both male and female humans (2.9 and 4.0 fold respectively) [16, 17] and monkeys (4.1 fold) [15], while the expression of GADD45a has been shown to be elevated in mouse gastrocnemius muscle (2.6 fold) [13] and both male and female human muscle (2.0 and 1.9 fold respectively) [16]. Because the expression of these two genes is typically mediated by the action of p53, we decided to systematically examine our list of genes differentially expressed between young and old to determine if there were any other transcripts that are also connected to p53 activity. As shown in Table 2, the transcripts that are activated by p53, or whose gene products are known to bind to p53, increase significantly with age, while the expression of genes that are known to inhibit p53 activity decline in old muscle. The average CR prevention on these p53-related genes was 77%.

To confirm the age-related changes in expression observed in p21 and GADD45a using microarrays, we probed young, old and old CR mice using RT-PCR (Figure 1A). We also examined the expression levels of the p53 gene itself, along with the expression levels of another important tumor suppressor, p16. Both p53 and p16 transcripts were considered absent (below levels of background hybridization) in all animals according to the Affymetrix software, but we were able to detect expression using the more sensitive method of RT-PCR. As is shown in Figure 1A, transcript levels for these genes increased significantly (Student's t-test, P < 0.05) with age. Furthermore, old animals undergoing CR demonstrated reduced levels for these genes compared to age-matched mice fed normal diets (only the difference in p53 levels was considered significant at P < 0.05). To examine how the expression of p21, p16, GADD45a and p53 is altered over the course of the adult mouse life span, we used RT-PCR to measure transcript levels for these genes in gastrocnemius muscle at 5 month intervals from 5 to 30 months of age (Figure 1B–E). With the exception of GADD45a (Figure 1D), the increase in expression of these genes does not show a linear pattern with age. p16 and GADD45a expression increases significantly only in the last third of the lifespan, whereas expression of p53 and its transcriptional target p21 occur as early as 10 months of age.

To determine whether the p53-mediated transcriptional program observed in older mouse skeletal muscle translated into higher levels of p53-associated proteins being expressed, we probed young, old and old CR muscle for p53-transcriptional targets p21 and GADD45a. Western immunoblot confirmed a significant increase in p21 protein (4.6 fold, P < 0.005) and GADD45a (1.6 fold, P < 0.05) in older mouse skeletal muscle (Figure 2). Levels for these proteins were reduced in the old CR mice as compared to old mice on the control diet (approximately 57% and 77% of old levels for p21 and GADD45a respectively). An attempt was made with several antibodies to measure p53 protein levels (both phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated isoforms) in GN muscle, but the signal from the Western blots was either absent or too low to accurately quantitate p53 in any age group (data not shown).

p21 , p16 , Gadd45a and p53 expression in mouse skeletal muscle. (A) Relative expression ratio ± SE for mRNA levels, as determined by RT-PCR, for p21, p16, Gadd45a and p53 in young (5 month old), old (25 month old), and old CR (n = 5 for each group). (B-E) Relative expression ratio ± SE for mRNA levels for these genes over the course of the adult mouse life span (5 to 30 months of age). The mean of 5 mice ± SE was used for each data point on the graphs. Two-tailed Student's t-test; *P < 0.05 (young versus old) and †P < 0.05 (old verses old CR).

Protein levels for p21 and GADD45a in mouse skeletal muscle. (A) Representative western blot for p21 and GADD45a staining in young, old and old CR skeletal muscle. (B) Expression ratio information on protein levels (n = 3 and n = 4 for p21 and Gadd45a respectively for each age and diet). One-tailed Student's t-test; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 (young verses old), †P < 0.005 (old versus old CR).

Transcript Levels of p21, p16 and GADD45a in Mouse Models of Increased Oxidative Stress

To test whether the changes in expression of the p53-related genes could be attributed to cumulative oxidative damage with age, we compared transcript levels for p21, p16, GADD45a and p53 in C57BL/6 mice with a heterozygous knockout for either glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4+/-) (5 mo old) or MnSOD (SOD2+/-) (~9 mo old) mutations to age-matched wild-type mice. GPX4+/-mice have approximately half the amount of mRNA and protein levels for this essential Se-dependent antioxidant protein as compared to wild type mice [19]. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from mice heterozygous for the gpx4 gene show increased evidence of lipid and DNA oxidation, and are sensitive to gamma irradiation [19, 20]. SOD2+/- mice show a ~50% reduction in MnSOD protein content and MnSOD activity in gatrocnemius tissue [21] and have increased oxidative damage as demonstrated by significantly elevated levels of 8-oxo-2-deoxyguanosine (8oxodG) in both nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in all surveyed tissues compared to wild type mice [22]. RT-PCR analysis of p21, p16, GADD45a and p53, in GPX4+/- mice showed a significant increase (P < 0.005) in p53 expression compared to the age-matched wild-type mice. We did observe a ~2 fold increase in p16, although it was not statistically significant (P < 0.12). Transcript levels of these genes were not significantly different between SOD2+/- mice and age-matched controls [see additional file 2]. Thus, constitutive oxidative damage does not always trigger the expression of the genes examined. Possibly, different types of DNA damage in GPX4-/+ and SOD2+/- mice explain the observed differences.

Increased p53 Levels in Older Muscle is Associated with Increased Expression of Genes Involved in p53-Mediated Apoptosis

A critical function of p53 is the induction of apoptosis in cells that have undergone DNA damage or exhibit uncontrolled cellular growth [23]. To investigate whether increased p53 activity with age is associated with transcription profiles indicative of apoptosis in old gastrocnemius muscle, we examined mRNA levels of four genes known to be key transducers of p53-mediated apoptosis: Bcl-2 binding component 3 (bbc3/puma) [24], phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced protein 1 (pmaip1/noxa) [25], tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10b (tnfrsf10b/killer/dr5) [26] and Bcl-2-related ovarian killer protein (bok) [27]. We observed a significant increase in mRNA levels with age for these genes in mouse gastrocnemius muscle and a significant decrease in levels due to caloric restriction in old, age-matched controls (Figure 3A). The expression levels for all of these p53-mediators of apoptosis were also examined in the gastrocnemius muscle over the course of the mouse adult lifespan (Figure 3B–E), and increased levels of transcript were usually observed in the first half of the lifespan. We also compared the levels for these proapoptotic genes in the gastrocnemius tissue of GPX4+/- and the SOD+/- mice to age-matched wild type mice using RT-PCR. Only the levels for tnfrsf10b were considered significantly higher (P < 0.005) in the GPX4+/- mice while expression of these genes was not significantly different in the SOD2+/- mice [see additional file 3]. These findings indicate that p53-dependent mediators of apoptosis are regulated with age and that the mechanism of activation is independent of endogenous levels of oxidative stress.

RT-PCR of proapoptotic bbc3 , pmaip1 , tnfrsf10b and bok expression in mouse skeletal muscle. (A) Relative expression ratio ± SE for mRNA levels of p53-mediated apoptotic genes in young, old, and old CR (n = 5 for each group). The mRNA levels for these four genes were also measured using RT-PCR in 5–30 month old C57BL/6NHsd mouse gastrocnemius muscle (B-E) (mean ± SE of 5 animals per age group). Two-tailed Student's t-test; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 (young verses old), †P < 0.05 (old versus old CR).

Increase in mRNA Levels of p53 and p53-Associated Genes in Multiple Tissues of Old C57Bl6/J Mice

To determine whether the p53-mediated transcriptional program we observe in older skeletal muscle may also occur in other tissues, we used RT-PCR to measure mRNA levels of p53-associated genes in heart, lung, liver, kidney, brain and intestine of young, old, and old CR mice (Table 3). Transcript levels for p21, p16, p53 and pmaip1 demonstrated increased levels in multiple tissue types in the old mice, while an increase in transcript levels for gadd45a, bbc3, tnfrsf10b and bok was only observed in old skeletal muscle. These findings suggest that activation of a p53-mediated transcriptional program may be a common feature of aging in multiple tissues, but the pattern of expression of p53-dependent genes is tissue specific.

Discussion and conclusion

Our initial investigation of muscle aging in mice revealed many differences in the transcriptional patterns between young and old mice [13]. In general, transcript levels for genes that are associated with cellular damage were elevated in older muscle, while transcript levels for genes involved in energy metabolism were reduced with age. The current study further demonstrates that the intrinsic transcriptional patterns are altered with aging in mouse skeletal muscle. As with other microarray studies done on older mammalian muscle [13–17], we have also found a disproportionate number of metabolic genes, such as those involved in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism, decrease in transcription levels with age. The age-related decrease in expression of these energy-associated classes likely reflects the reduction in mitochondria observed in older gastrocnemius muscle. For example, a 23–25% reduction in mtDNA copy number and a corresponding 17–22% reduction in the expression of mitochondrial DNA-encoded cytochrome c oxidase (COX) subunits I and III was previously reported in old rat gastrocnemius tissue [28]. In our study, out of 25 transcripts that are associated with the mitochondria, the expression of 18 of these probe sets are significantly reduced with age (PP < .90) [see additional file 1]. Conversely, genes associated with the stress and immune response, such as those involved in the induction of apoptosis or the response to DNA damage, have elevated mRNA levels in the older animals. The age-associated increase in genes that are activated during cellular stress and injury is probably in response to a wide variety of biological damage known to accumulate in older muscle over the course of the lifespan [9, 10, 12]. We also observed that the expressions of a large number of genes involved in the regulation of the cell cycle were increased with age in mouse skeletal muscle. A closer examination of these cell cycle genes revealed a pattern of expression indicative of increased p53 activity in older mouse muscle (Table 2).

Welle et al. also found transcriptional evidence of increased p53 activity with age in the skeletal muscle of young (20–29 yrs. old) and old (65–71 yrs. old) women [16]. In their study, genes that regulate or enhance p53 activity (Pin1, p57 and Wrn) or that are induced by p53 (p21 and GADD45a) demonstrate increased expression in older female muscle. Based on this evidence, Welle and coworkers suggested that future studies should examine the possibility that p53 levels or activity are increased in older muscle. One possible mechanism for the observed increase in p53 activity is elevated levels of DNA damage with age. The concentration of 8-oxo-2 deoxyguanosine (oxo8dG), a byproduct of DNA oxidation, has been observed to increase with age in a variety of tissues, including skeletal muscle, in rats and various strains of mice (CR reduced the levels of oxo8dG in most of these tissues) [29]. We tested this hypothesis by examining the levels of p53 mRNA and related transcripts in transgenic mice with half the wild type levels of antioxidants GPX4 or SOD2. These mice have elevated levels of oxidative DNA damage yet failed to show any significant increase in expression of p21 and GADD45a, two well studied p53-induced genes [see additional file 2]. The GPX4+/- mice did display a significant increase in transcript levels for p53 as compared to age-matched controls, but no change was observed for the SOD2+/- mice. Possibly, different types of DNA damage impact the expression of these genes differently. Another possibility is that the DNA damage signaling that is the trigger for activation of p53 in old muscle originates from chromosomal damage, such as double-strand breaks or telomere shortening, rather than from oxidative alterations. We also note that there are two likely possibilities for the cellular origin of the alteration in expression of cell cycle regulators. One is that these alterations in gene expression reflect a decline in proliferation of a muscle-associated cell such as the satellite cell. It has recently been reported that hematopoietic stem cell numbers are higher in old mice with reduced p53 activity (p53+/-) and fail to increase with age in old mice with hypermorphic p53 activity (p53+/m) as compared to their wild type counterparts [30]. A second possibility is that the expression of these genes reflects a general p53-mediated DNA damage response associated with age-related DNA modifications in myocytes.

Many recent studies have linked tumor suppressor activity, in particular the tumor suppressor p53, to organismal aging [23, 31–34]. p16INK4a, a product of the INK4a/ARF (Cdkn2a) locus also increases in expression with age in most tissues as shown in previous studies [35–37] and also in the current analysis. This increase in p16INK4a expression with age has recently been shown to contribute to age-dependent decline in regenerative potential of pancreatic islet regenerative capacity [38], decreases in forebrain progenitors and neurogenesis [39] and the decrease in hematopoietic stem cell repopulation defects [40]. However, we note that it is possible that only rare cells in tissues express p16INK4a with aging. Under these conditions, a large effect of increased ROS in a specific biologically relevant muscle compartment (e.g. satellite cells) could be missed by studying unfractionated muscle as we did in our analysis. Thus, the induction of a cell senescence and apoptotic program with age may underlie key features of the aging process.

Given our finding that mRNA levels for p53-associated genes were elevated in multiple tissues of old mice (Table 3), our data suggests that increased p53 activity is not limited to aging muscle but is also an overall consequence of organismal aging. Increased p53 mRNA levels is observed in the grey and white matter of the cortex, cerebellum, and medulla oblongata of old (24 month old) verses young (3.0–3.5 months old) rat brains and an increase in p53 protein levels is observed in the grey matter of old rats [41]. We did not find a significant difference in p53 gene expression between young and old brains, but our analysis was performed on whole brain homogenates and therefore any age-effect on p53 expression within the different regions of the brain might have been missed. Further support for the role of increased p53 activity contributing to aging process comes from transgenic studies in mice that express overactive p53 and also demonstrate accelerated aging [42, 43]. Mice with augmented p53 function develop typical age-associated phenotypes such as delayed wound healing, reduced hair growth and reduced subcutaneous adipose tissue much earlier than their p53 wild type counterparts. Conversely, the long-lived p66Shc-/- mouse, shown to have a 30% extended life span, exhibits impaired p53 apoptotic signaling [44]. Our study demonstrates that the majority of the p53-related transcriptional changes observed in old skeletal muscle are either completely or partially reversed through caloric restriction, a proven method to extended longevity. Based on the evidence for the involvement of the p53 pathway in organismal aging, it follows that p53 and p53 transcriptional targets have the potential to be good biomarkers of aging in multiple tissue types.

It has been well documented that there is a significant decrease in muscle mass with age, yet little is known as to the actual mechanism for this loss of tissue. It has been hypothesized that the decrease in muscle fiber can be attributed to increased apoptosis with age. In fact, an increase in biological markers of apoptosis, such as DNA fragmentation and proapoptotic caspase-type proteins, are increased with age in human [45] and rat skeletal muscle [46, 47]. However, the mechanism for this age-associated apoptosis is unknown. It has been suggested that increased oxidative damage to the mitochondria, along with sarcoplasmic reticulum stress in older skeletal muscle could initiate caspase activation and lead to the apoptotic pathway that ultimately results in the destruction of the aged myocyte [47]. Moreover, Dirks and Leeuwenburgh also observed a significant reduction in DNA fragmentation (mono- and oligonucleosomes) and caspase levels in old (26 month old) rats on lifelong caloric restriction when compared to their age-matched, ad libitum-fed counterparts. The authors suggest the reduction of apoptosis in response to caloric restriction is due to reduced mitochondrial oxidant production and nuclear oxidative DNA damage in skeletal muscle [48]. Our results do not support this hypothesis. Although young GPX4+/- mice did show increased levels of expression, compared to wild-type young mice, of p53-associated mediator of apoptosis tnfrsf10b, little or no change was observed for bbc3 and bok (only tnfrsf10b was considered significant at P < 0.05). The SOD2+/- mice, on the other hand, demonstrated almost identical levels of expression for all of the surveyed p53 mediators of apoptosis to the age-matched, wild type controls. It is possible that increased oxidative damage may play a role in p53-mediated apoptosis in older muscle, but our data suggests that it may not be the sole causative effect. Old calorie restricted mice displayed a significant decrease in expression levels of all four of the p53-mediators of apoptosis compared to the normally fed old mice. It is clear that caloric restriction has an inhibitory effect on age-associated apoptosis of skeletal muscle, but this prevention may not be completely explained by the reduction of endogenous reactive oxygen species and the resulting decrease in oxidative DNA damage in these animals.

The role of p53 in the aging process of skeletal muscle is likely to be a complex process involving many different cellular effectors. Various proteins and pathways interact with p53 to modulate its activity. Furthermore, there are numerous p53-transcriptional targets, each with their own associated modulators that may influence muscle aging. As evidence of this complexity, we show that the expression profiles for p53-regulated genes are not identical to that of p53, as well as to each other, over the course of the mouse adult lifespan in gastrocnemius muscle (Figure 1B–E, Figure 3B–E). Future studies will concentrate on determining which specific components of the p53 pathway play a functional role in muscle aging, and organismal aging in general.

Methods

Animal treatments

Male C57BL/6NHsd mice were purchased from Harlan Sprague-Dawley at 6–7 weeks of age and individually housed for the remainder of their lifespan. Upon arrival to our facility, mice were fed one of two life-long dietary regimens: normal diet (ND) and caloric restriction (CR). Mice on ND were provided acidic water ad libitum and fed 84 kcal/wk which is ~15% less than the average ad libitum diet. C57BL/6NHsd mice on this dietary regiment typically have an average lifespan of 30 mo. in our colony. Mice on CR were fed a diet that resulted in a 26% difference in caloric intake to the ND animals. The diet fed to CR mice was enriched in protein, vitamins and minerals such that CR and ND mice were fed nearly identical amounts of these components. Detailed information on diet composition and feeding for ND and CR mouse diets have previously been described [49]. Five replicate mice were used for each diet and age group for microarray analysis. Dissected gastrocnemius muscle from the mice were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until processed for microarray or Western analysis.

Tissue preparation and oligonucleotide array hybridization

RNA was extracted from frozen mouse tissue, transcribed to cDNA which was then used as a template to produce biotin-labeled cRNA as previously described [50]. A total of 10 μg of fragmented cRNA was used for hybridization to each MOE430A array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). After hybridization, the arrays were washed and stained with signal amplification protocol using antibody. The arrays were scanned twice and the averaged images were used for further analysis.

Data analysis

The complete set of gene expression data has been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database [51] accession # [GSE6323]. Robust Multi-Array Analysis (RMA) was used to pre-process and normalize the raw Affymetrix GeneChip data [52]. RMA is available in Bioconductor [53], an open source and open development software project for the analysis and comprehension of genomic data based primarily on the R programming language [54]. RMA fits a log-scale linear model to derive a single, normalized, summary score of expression for each probe on each array. RMA has been shown to provide greater sensitivity and specificity in detection of differentially expressed genes than the Affymetrix analysis software MAS 5.0 [52, 54]. Because RMA generally provides attenuated estimates of fold-change [55], the values reported in the expression ratios for the array data are likely minimal estimates. MAS5.0 was used to compute absent/present calls. Any gene considered absent across all 15 arrays was removed from the analysis. This left 10,892 probes (out of 22,690).

Statistical analysis

To identify genes differentially expressed over time, we used an empirical Bayes hierarchical modeling approach called EBarrays [56, 57], also implemented in Bioconductor [54]. To briefly illustrate EBarrays, first consider the simple case of two biological conditions. For a given gene g, there are then two underlying levels of expression, one in each condition. These are the quantities of interest that are approximated by the expression measurements. Of most interest is the relationship between these means. In the case of equivalent expression (EE), the two means denoted by μg1 and μg2 are equal; μg1 ≠ μg2 denotes differential expression (DE). We refer to these equality and inequality relationships as expression patterns.

EBarrays assigns a probability to each gene for each pattern. To do this, the probability distribution governing the data must be described. A Gamma-Gamma (GG) model is often used. For that model, we assume the underlying expression levels are approximately distributed as Inverse Gamma; and, for a given gene g in condition k (in our simple example, k = 1,2), measured intensities arise from a Gamma distribution with mean μgk. The Inverse Gamma distribution here describes variation in the true underlying intensity levels of different genes (some genes have low expression, others high) and the Gamma distribution describes within gene variability due to biological and technical error variations. Similarly, a log-Normal Normal (LNN) model can also be used, where the underlying expression levels are assumed Gaussian, and log intensities for gene g in condition k are considered as Normally distributed with mean prescribed by μgk. Since we never know which genes are in which patterns, the full data distribution is given by a mixture: there is some probability p that the data for a given gene arise from pattern DE and a (1-p) chance that the data are EE.

For both cases, model parameters are determined by fitting the model to the full set of array data (details are given in [57]). In this way, the approach utilizes information across genes and arrays to optimize model fit, and is thus more efficient than a number of methods that make gene inferences one gene at a time. Once model parameters are obtained, probabilities for each pattern are calculated for every gene. These probabilities are referred to as posterior probabilities, since they are calculated after observing a set of data. For a given gene and expression pattern, the posterior probability quantifies evidence that the gene is in that pattern. Posterior probability thresholds can be set to control the false discovery rate (FDR) at a desired level [58]. For example, defining DE genes to be those with a posterior probability of DE exceeding 0.95 controls the FDR at 0.05.

This approach, described for two conditions, extends naturally to multiple conditions. Whereas for two biological conditions there are only the EE and DE patterns to consider, for multiple conditions there are many patterns. Given the three conditions here (young, old, and old CR), 5 expression patterns are possible (μ1 = μ2 = μ3; μ1 ≠ μ2 = μ3; μ1 = μ2 ≠ μ3; μ1 = μ3≠μ2; μ1≠μ2≠μ3). Model fit proceeds as in the two-pattern case (the details of the multiple pattern case are also given in [57]). Posterior probabilities for each of the 5 patterns were calculated for 10,892 genes under both GG and LNN assumptions. The appropriateness of model assumptions was checked using diagnostic plots. In most cases, results were similar for both models and only results from the LNN model are reported.

Real-time (RT)-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from frozen tissue using the TRIZOL reagent (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Polyadenylate [poly(A)+] RNA (mRNA) was then purified from the total RNA with oligo-dT-linked oligotex resin (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Isolated mRNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA and amplified using the TaqMan EZ RT-PCR Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) (5 ng mRNA per 25 μl RT-PCR reaction volume). All primers and fluorescent probes for assayed genes, with the exception of the custom-made p21 and p16, were purchased from Assays-on-Demand Gene Expression probes (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The gene symbol and Applied Biosystem assay number for all Assays-on-Demand primer/probe sets used for RT-PCR are as follows: gadd45 (Mm00432802_m1), p53 (Mm00441964_g1), bbc3 (Mm00519268_m1), pmaip1 (Mm00451763_m1), tnfrsf10b (Mm00457866_m1), bok (Mm00479422_m1), tbp (Mm00446973_m1), and gapd (Mm99999915_g1). The sequence for the primers and probes for p21 and p16 are as follows: for p21, forward 5'-GGCAGACCAGCCTGACAGAT-3', reverse 5'-TTCAGGGTTTTCTCTTGCAGAAG-3', and probe 5'-TCTATCACTCCAAGGCA-3'; for p16, forward 5'- CCCAACGCCCCGAACT-3', reverse 5'- GCAGAAGAGCTGCTACGTGAA-3', and probe 5'-TTCGGTCGTACCCCGATTCAGGTG-3'. The sequence for the RT-PCR probe and primer for p16 was provided to us by Norman Sharpless's research group. The expression of TATA box binding protein (tbp) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gapd), which showed approximately the same expression levels as measured on the microarrays for all animals regardless of age or diet, was used to normalize all RT-PCR results. RT-PCR was performed and quantified using the ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Western immunoblot

Tissues homogenate was prepared from frozen in modified RIPA buffer (Tris-HCL 50 mM pH 7.4, NP-40 1%, Na-deoxycholate 0.25%, NaCl 150 mM EDTA 1 mM) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma). One hundred micrograms of each tissue extract were separated on 12.5% SDS PAGE gel (BioRad) and transferred to PVDF membrane (Pierce). Membranes were blocked in 5% milk in Tris buffered saline 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 hour. Membranes were incubated in primary antibody overnight at 4°C with agitation in either 5% milk or 5% BSA in TBST at the indicated dilutions (GADD45A Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. 1:500; p21/WAF1 Ab-6 Calbiochem 1:4000; Tubulin Sigma 1:2000). After 3 × 5 min washes, the membranes were incubated in HRP conjugated secondary antibody (Vector labs, 1:10,000 dilution) for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were washed as before, incubated in SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce) and exposed to film (Pierce). Band density was calculated using NIH Image J software.

References

Kamel HK: Sarcopenia and aging. Nutr Rev. 2003, 61: 157-167. 10.1301/nr.2003.may.157-167.

Fiatarone MA, O'Neill EF, Ryan ND, Clements KM, Solares GR, Nelson ME, Roberts SB, Kehayias JJ, Lipsitz LA, Evans WJ: Exercise training and nutritional supplementation for physical frailty in very elderly people. N Engl J Med. 1994, 330: 1769-1775. 10.1056/NEJM199406233302501.

Dutta C, Hadley EC, Lexell J: Sarcopenia and physical performance in old age: overview. Muscle Nerve Suppl. 1997, 5: S5-9. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(1997)5+<5::AID-MUS2>3.0.CO;2-E.

Kenney WL, Buskirk ER: Functional consequences of sarcopenia: effects on thermoregulation. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995, 50 Spec No: 78-85.

Bendall MJ, Bassey EJ, Pearson MB: Factors affecting walking speed of elderly people. Age Ageing. 1989, 18: 327-332. 10.1093/ageing/18.5.327.

Roubenoff R: Catabolism of aging: is it an inflammatory process?. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2003, 6: 295-299. 10.1097/00075197-200305000-00005.

Pedersen M, Bruunsgaard H, Weis N, Hendel HW, Andreassen BU, Eldrup E, Dela F, Pedersen BK: Circulating levels of TNF-alpha and IL-6-relation to truncal fat mass and muscle mass in healthy elderly individuals and in patients with type-2 diabetes. Mech Ageing Dev. 2003, 124: 495-502. 10.1016/S0047-6374(03)00027-7.

Pugh TD, Klopp RG, Weindruch R: Controlling caloric consumption: protocols for rodents and rhesus monkeys. Neurobiol Aging. 1999, 20: 157-165. 10.1016/S0197-4580(99)00043-3.

Welle S, Thornton C, Jozefowicz R, Statt M: Myofibrillar protein synthesis in young and old men. Am J Physiol. 1993, 264: E693-8.

Mecocci P, Fano G, Fulle S, MacGarvey U, Shinobu L, Polidori MC, Cherubini A, Vecchiet J, Senin U, Beal MF: Age-dependent increases in oxidative damage to DNA, lipids, and proteins in human skeletal muscle. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999, 26: 303-308. 10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00208-1.

Sohal RS, Agarwal S, Candas M, Forster MJ, Lal H: Effect of age and caloric restriction on DNA oxidative damage in different tissues of C57BL/6 mice. Mech Ageing Dev. 1994, 76: 215-224. 10.1016/0047-6374(94)91595-4.

Lee CM, Lopez ME, Weindruch R, Aiken JM: Association of age-related mitochondrial abnormalities with skeletal muscle fiber atrophy. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998, 25: 964-972. 10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00185-3.

Lee CK, Klopp RG, Weindruch R, Prolla TA: Gene expression profile of aging and its retardation by caloric restriction. Science. 1999, 285: 1390-1393. 10.1126/science.285.5432.1390.

Sreekumar R, Unnikrishnan J, Fu A, Nygren J, Short KR, Schimke J, Barazzoni R, Nair KS: Effects of caloric restriction on mitochondrial function and gene transcripts in rat muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002, 283: E38-43.

Kayo T, Allison DB, Weindruch R, Prolla TA: Influences of aging and caloric restriction on the transcriptional profile of skeletal muscle from rhesus monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001, 98: 5093-5098. 10.1073/pnas.081061898.

Welle S, Brooks AI, Delehanty JM, Needler N, Bhatt K, Shah B, Thornton CA: Skeletal muscle gene expression profiles in 20-29 year old and 65-71 year old women. Exp Gerontol. 2004, 39: 369-377. 10.1016/j.exger.2003.11.011.

Welle S, Brooks AI, Delehanty JM, Needler N, Thornton CA: Gene expression profile of aging in human muscle. Physiol Genomics. 2003, 14: 149-159.

Lekstrom-Himes J, Xanthopoulos KG: Biological role of the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein family of transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 1998, 273: 28545-28548. 10.1074/jbc.273.44.28545.

Yant LJ, Ran Q, Rao L, Van Remmen H, Shibatani T, Belter JG, Motta L, Richardson A, Prolla TA: The selenoprotein GPX4 is essential for mouse development and protects from radiation and oxidative damage insults. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003, 34: 496-502. 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)01360-6.

Ran Q, Van Remmen H, Gu M, Qi W, Roberts LJ, Prolla T, Richardson A: Embryonic fibroblasts from Gpx4+/- mice: a novel model for studying the role of membrane peroxidation in biological processes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003, 35: 1101-1109. 10.1016/S0891-5849(03)00466-0.

McArdle A, van der Meulen J, Close GL, Pattwell D, Van Remmen H, Huang TT, Richardson AG, Epstein CJ, Faulkner JA, Jackson MJ: Role of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase in contraction-induced generation of reactive oxygen species in skeletal muscle extracellular space. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004, 286: C1152-8. 10.1152/ajpcell.00322.2003.

Van Remmen H, Ikeno Y, Hamilton M, Pahlavani M, Wolf N, Thorpe SR, Alderson NL, Baynes JW, Epstein CJ, Huang TT, Nelson J, Strong R, Richardson A: Life-long reduction in MnSOD activity results in increased DNA damage and higher incidence of cancer but does not accelerate aging. Physiol Genomics. 2003, 16: 29-37. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00122.2003.

Sharpless NE, DePinho RA: p53: good cop/bad cop. Cell. 2002, 110: 9-12. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00818-8.

Yu J, Wang Z, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Zhang L: PUMA mediates the apoptotic response to p53 in colorectal cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003, 100: 1931-1936. 10.1073/pnas.2627984100.

Eferl R, Ricci R, Kenner L, Zenz R, David JP, Rath M, Wagner EF: Liver tumor development. c-Jun antagonizes the proapoptotic activity of p53. Cell. 2003, 112: 181-192. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00042-4.

Wu GS, Burns TF, McDonald ER, Jiang W, Meng R, Krantz ID, Kao G, Gan DD, Zhou JY, Muschel R, Hamilton SR, Spinner NB, Markowitz S, Wu G, el-Deiry WS: KILLER/DR5 is a DNA damage-inducible p53-regulated death receptor gene. Nat Genet. 1997, 17: 141-143. 10.1038/ng1097-141.

Yakovlev AG, Di Giovanni S, Wang G, Liu W, Stoica B, Faden AI: Bok and Noxa are essential mediators of p53-dependent apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004

Barazzoni R, Short KR, Nair KS: Effects of aging on mitochondrial DNA copy number and cytochrome c oxidase gene expression in rat skeletal muscle, liver, and heart. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275: 3343-3347. 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3343.

Hamilton ML, Van Remmen H, Drake JA, Yang H, Guo ZM, Kewitt K, Walter CA, Richardson A: Does oxidative damage to DNA increase with age?. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001, 98: 10469-10474. 10.1073/pnas.171202698.

Dumble M, Moore L, Chambers SM, Geiger H, Van Zant G, Goodell MA, Donehower LA: The impact of altered p53 dosage on hematopoietic stem cell dynamics during aging. Blood. 2006

Marcotte R, Wang E: Replicative senescence revisited. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002, 57: B257-69.

Clarke AR, Hollstein M: Mouse models with modified p53 sequences to study cancer and ageing. Cell Death Differ. 2003, 10: 443-450. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401188.

Donehower LA: Does p53 affect organismal aging?. J Cell Physiol. 2002, 192: 23-33. 10.1002/jcp.10104.

Pelicci PG: Do tumor-suppressive mechanisms contribute to organism aging by inducing stem cell senescence?. J Clin Invest. 2004, 113: 4-7. 10.1172/JCI200420750.

Nielsen GP, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, Shaw J, Roy JE, Koh J, Louis DN: Immunohistochemical survey of p16INK4A expression in normal human adult and infant tissues. Lab Invest. 1999, 79: 1137-1143.

Zindy F, Quelle DE, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ: Expression of the p16INK4a tumor suppressor versus other INK4 family members during mouse development and aging. Oncogene. 1997, 15: 203-211. 10.1038/sj.onc.1201178.

Krishnamurthy J, Torrice C, Ramsey MR, Kovalev GI, Al-Regaiey K, Su L, Sharpless NE: Ink4a/Arf expression is a biomarker of aging. J Clin Invest. 2004, 114: 1299-1307. 10.1172/JCI200422475.

Krishnamurthy J, Ramsey MR, Ligon KL, Torrice C, Koh A, Bonner-Weir S, Sharpless NE: p16(INK4a) induces an age-dependent decline in islet regenerative potential. Nature. 2006

Molofsky AV, Slutsky SG, Joseph NM, He S, Pardal R, Krishnamurthy J, Sharpless NE, Morrison SJ: Increasing p16(INK4a) expression decreases forebrain progenitors and neurogenesis during ageing. Nature. 2006

Janzen V, Forkert R, Fleming HE, Saito Y, Waring MT, Dombkowski DM, Cheng T, Depinho RA, Sharpless NE, Scadden DT: Stem-cell ageing modified by the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16(INK4a). Nature. 2006

Dorszewska J, Adamczewska-Goncerzewicz Z: Oxidative damage to DNA, p53 gene expression and p53 protein level in the process of aging in rat brain. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2004, 139: 227-236. 10.1016/j.resp.2003.10.005.

Maier B, Gluba W, Bernier B, Turner T, Mohammad K, Guise T, Sutherland A, Thorner M, Scrable H: Modulation of mammalian life span by the short isoform of p53. Genes Dev. 2004, 18: 306-319. 10.1101/gad.1162404.

Tyner SD, Venkatachalam S, Choi J, Jones S, Ghebranious N, Igelmann H, Lu X, Soron G, Cooper B, Brayton C, Hee Park S, Thompson T, Karsenty G, Bradley A, Donehower LA: p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotypes. Nature. 2002, 415: 45-53. 10.1038/415045a.

Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Mele S, Pelicci G, Reboldi P, Pandolfi PP, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci PG: The p66shc adaptor protein controls oxidative stress response and life span in mammals. Nature. 1999, 402: 309-313. 10.1038/46311.

Strasser H, Tiefenthaler M, Steinlechner M, Eder I, Bartsch G, Konwalinka G: Age dependent apoptosis and loss of rhabdosphincter cells. J Urol. 2000, 164: 1781-1785. 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)67106-6.

Dirks A, Leeuwenburgh C: Apoptosis in skeletal muscle with aging. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002, 282: R519-27.

Dirks AJ, Leeuwenburgh C: Aging and lifelong calorie restriction result in adaptations of skeletal muscle apoptosis repressor, apoptosis-inducing factor, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis, caspase-3, and caspase-12. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004, 36: 27-39. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.10.003.

Drew B, Phaneuf S, Dirks A, Selman C, Gredilla R, Lezza A, Barja G, Leeuwenburgh C: Effects of aging and caloric restriction on mitochondrial energy production in gastrocnemius muscle and heart. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003, 284: R474-80.

Pugh TD, Oberley TD, Weindruch R: Dietary intervention at middle age: caloric restriction but not dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate increases lifespan and lifetime cancer incidence in mice. Cancer Res. 1999, 59: 1642-1648.

Edwards MG, Sarkar D, Klopp R, Morrow JD, Weindruch R, Prolla TA: Age-related impairment of the transcriptional responses to oxidative stress in the mouse heart. Physiol Genomics. 2003, 13: 119-127.

Gene Expression Omnibus database. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/]

Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP: Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003, 4: 249-264. 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249.

Bioconductor. [http://www.bioconductor.org/download]

Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, Hornik K, Hothorn T, Huber W, Iacus S, Irizarry R, Leisch F, Li C, Maechler M, Rossini AJ, Sawitzki G, Smith C, Smyth G, Tierney L, Yang JY, Zhang J: Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004, 5: R80-10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80.

Wu Z, Irizarry RA, Gentleman RC, Martinez-Murillo F, Spencer F: A Model-Based Background Adjustment for Oligonucleotide Expression Arrays. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2004, 99: 909-917. 10.1198/016214504000000683.

Newton MA, Kendziorski CM, Richmond CS, Blattner FR, Tsui KW: On differential variability of expression ratios: improving statistical inference about gene expression changes from microarray data. J Comput Biol. 2001, 8: 37-52. 10.1089/106652701300099074.

Kendziorski CM, Newton MA, Lan H, Gould MN: On parametric empirical Bayes methods for comparing multiple groups using replicated gene expression profiles. Stat Med. 2003, 22: 3899-3914. 10.1002/sim.1548.

Newton MA, Noueiry A, Sarkar D, Ahlquist P: Detecting differential gene expression with a semiparametric hierarchical mixture method. Biostatistics. 2004, 5: 155-176. 10.1093/biostatistics/5.2.155.

Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarver L, Kasarskis A, Lewis S, Matese JC, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G: Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000, 25: 25-29. 10.1038/75556.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

ME performed most of the experiments in the paper and wrote the first draft and contributed to all subsequent drafts of the manuscript. RA performed all of the Western work. CK and MY performed the statistical analysis on the microarray data. RW provided all of the mice used in the study and served as advisor for this project. TP was the overall director of the research, provided the funds for this study, and contributed to the writing and editing of this manuscript. All authors have read and approved of the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12864_2006_793_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional file 1: Transcripts with age effect in mouse gastrocnemius muscle. Table of transcripts, listed alphabetically, that increased or decreased significantly (PP > 0.90) with age in mouse gastrocnemius muscle. (PDF 150 KB)

12864_2006_793_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Additional file 2: Expression of p53-related genes in wild type and transgenic GPX4 and MnSOD mice. Relative expression ratio ± SE for mRNA levels, as determined by RT-PCR, for p21, p16, Gadd45a and p53 in (a) 5 month old GPX+/+ and GPX+/- and (b) 9 month old SOD+/+ and SOD+/- gastrocnemius muscle (n = 5 for each group). Only the expression of p53 was considered significantly different (Student's T-Test; *P < 0.05) between GPX+/+ and GPX+/- mice. (PDF 12 KB)

12864_2006_793_MOESM3_ESM.pdf

Additional file 3: Expression of p53-mediated proapoptotic genes in wild type and transgenic GPX4 and MnSOD mice. Relative expression ratio ± SE for mRNA levels, as determined by RT-PCR, for Bbc3 (Puma), Pmaip1 (Noxa), Tnfrsf10b (Killer/Dr5) and Bok in (a) 5 month old GPX+/+ and GPX+/- and (b) 9 month old SOD+/+ and SOD+/- gastrocnemius muscle (n = 5 for each group). Only the expression of Tnfrsf10b was considered significantly different (Student's T-Test; *P < 0.05) between GPX+/+ and GPX+/- mice. (PDF 13 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Edwards, M.G., Anderson, R.M., Yuan, M. et al. Gene expression profiling of aging reveals activation of a p53-mediated transcriptional program. BMC Genomics 8, 80 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-8-80

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-8-80