Abstract

Background

Gamma-proteobacteria, such as Escherichia coli, can use a variety of respiratory substrates employing numerous aerobic and anaerobic respiratory systems controlled by multiple transcription regulators. Thus, in E. coli, global control of respiration is mediated by four transcription factors, Fnr, ArcA, NarL and NarP. However, in other Gamma-proteobacteria the composition of global respiration regulators may be different.

Results

In this study we applied a comparative genomic approach to the analysis of three global regulatory systems, Fnr, ArcA and NarP. These systems were studied in available genomes containing these three regulators, but lacking NarL. So, we considered several representatives of Pasteurellaceae, Vibrionaceae and Yersinia spp. As a result, we identified new regulon members, functioning in respiration, central metabolism (glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, pentose phosphate pathway, citrate cicle, metabolism of pyruvate and lactate), metabolism of carbohydrates and fatty acids, transcriptional regulation and transport, in particular: the ATP synthase operon atpIBEFHAGCD, Na+-exporting NADH dehydrogenase operon nqrABCDEF, the D-amino acids dehydrogenase operon dadAX. Using an extension of the comparative technique, we demonstrated taxon-specific changes in regulatory interactions and predicted taxon-specific regulatory cascades.

Conclusion

A comparative genomic technique was applied to the analysis of global regulation of respiration in ten gamma-proteobacterial genomes. Three structurally different but functionally related regulatory systems were described. A correlation between the regulon size and the position of a transcription factor in regulatory cascades was observed: regulators with larger regulons tend to occupy top positions in the cascades. On the other hand, there is no obvious link to differences in the species' lifestyles and metabolic capabilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Escherichia coli, the best-studied representative of gamma-proteobacteria, can adapt to a wide variety of environmental conditions. One source of this capability is the presence of numerous aerobic and anaerobic respiratory systems. To adapt to different growth conditions, this bacterium alter the composition of their respiratory systems by changing the repertoire of substrate-specific dehydrogenases and terminal oxidoreductases. The concentration of each component is strictly regulated in order to optimize the respiratory chains according to the available substrates and the physiological needs of the cell.

In facultative anaerobe E. coli, regulation of respiration depends on the availability of electron acceptors, which are used in a specific order. Thus, molecular oxygen represses all other types of respiration and fermentation. Under anaerobiosis, nitrate, the most favorable electron acceptor in such conditions, represses other types of anaerobic respiration and fermentation. This control is effected by a variety of regulatory systems [1, 2].

The first level of regulation is implemented via the Fnr protein. Fnr is an oxygen-sensitive transcription factor. Oxygen is sensed by iron-sulfur clusters formed by the N-terminal domain. Under anaerobic conditions, Fnr forms dimers that are capable of binding DNA, whereas in the presence of oxygen these clusters are reversibly destroyed and the dimers dissociate [3, 4]. Thus, Fnr is active only under anaerobic conditions, when it activates genes necessary for the anaerobic metabolism and represses genes for the aerobic respiration [2, 5]. In E. coli, Fnr is the top regulator of respiration, as it controls the expression of genes for other transcriptional factors [6, 7].

Another transcription factor regulating respiration is the ArcA protein. ArcA is a part of the ArcA-ArcB two-component system, where ArcB is an inner membrane sensor protein. ArcB is belived to sense the redox state of ubiquinones: in vitro, the activity of this protein depends on the redox status of a ubiquionone soluble analog [8, 9]. In the absence of corresponding electron acceptors, ArcB phosphorylates ArcA, enabling it to bind DNA [10, 11]. Thus, under the anaerobic conditions, ArcA regulates expression of genes for respiration and central metabolism, and probably controls the switch between the respiration and fermentation metabolisms [5, 12–14].

The next level of regulation is provided by two homologous transcription factors, NarL and NarP. These proteins are activated in the presence of nitrate and nitrite by two homologous sensor kinases NarX and NarQ. The duplicated two-component system allows for the fine tuning of the nitrate and nitrite respiration system to a dynamic ratio of two alternative substrates. NarX and NarQ respond differentially to nitrate and nitrite. Thus, in this subsystem three levels of the response specificity may be distinguished: (i) interaction between sensor proteins and respiratory substrates, (ii) interaction between sensor proteins and transcription factors, and (iii) interaction between factors and their binding sites in DNA [15–18]. Upon activation, NarL and NarP activate genes for the nitrate and nitrate respiration and repress genes for other, less effective, pathways of anaerobic respiration [19–22].

Nevertheless, in some gamma-proteobacteria, only the single NarQ-NarP system was found [23], accompanied by reduction of the nitrate and nitrite respiratory system, and the presence of only the periplasmic respiratory system. So, in most gamma-proteobacteria the fine tuning of the system is not required and a single NarQ-NarP system is sufficient for the control of the nitrate and nitrite respiration [24].

Although the physiology and regulation of respiration in E. coli has been studied in considerable depth, the regulation in other organisms is poorly understood. Moreover, in other representatives of gamma-proteobacteria, for example, in Haemophilus influenzae, regulation of respiration looks to be quite different from E. coli [25, 26].

Previously, comparative genomic analyses were performed separately for Fnr [27], ArcA [28], and NarP [24] in a small number of microorganisms. Here we report the results of a comparative genomic analysis of the respiration regulation in multiple genomes belonging to several representatives of the three families of gamma-proteobacteria. Although the NarL-DNA interactions have been studied in experiment [29–32], the existing methods for prediction of transcription factor binding sites do not allow for the reliable identification of candidate NarL sites. Because of that, we analyzed the organisms containing only the NarP regulator. In such organisms, we studied three structurally different, but functionally related Fnr, ArcA and NarP systems.

Results

Structure of the Fnr, ArcA and NarP regulogs

The procedure described in "Methods" was applied to the analysis of regulation by Fnr, ArcA and NarP. All genes predicted to form regulogs (orthologous regulons) were classified according to their functions.

In comparison with previous studies, where single regulatory systems had been studied in several gamma-protoeobacterial genomes [24, 27, 33], here we predicted additional regulatory interactions. These predictions were made possible by the use of total pairwise comparison and detailed simultaneous analysis of multiple regulatory systems. Here we consider in detail only the relevant predictions. A summary of these predictions is given in Table 1, whereas more detailed data about site prediction, including information about operon structure changes, are shown in additional files 1 and 2.

Respiration

One of the most significant results was the identification of conserved candidate sites upstream of the atpIBEFHAGCD operon. This operon encodes all subunits of the ATP synthetase complex, the key component of the oxidative phosphorylation [34]. Experimental data about regulation of the atp operon in E. coli are conflicting. In particular, expression of the atp operon was claimed to be independent of Fnr or ArcA [35]. On the other hand, 1.5- to 8-fold increase of the expression level of various atp genes in the fnr mutant E. coli, as compared to the wild-type strain, was shown using a microarray assay [36]. Similarly, 1.9- to 14-fold increase of the expression level of various atp genes was shown in the arcA mutant strain [37]. Recently, candidate Fnr and ArcA sites were observed upstream of the atp operon in E. coli K-12 genome; these sites were conserved in many Enterobacteriaceae genomes [Tsiganova and Ravcheev, unpublished observation]. In the present study, candidate ArcA sites were observed upstream of the atp operon in both Yersinia spp., and Fnr sites were detected in all Vibrionaceae. Thus, in at least some gamma-proteobacteria, expression of the ATP synthetase genes is controlled by the global regulators of respiration.

Candidate regulatory sites were found upstream of the nqrABCDEF operon encoding Na+-exporting NADH dehydrogenase [38]. Candidate Fnr-binding sites are conserved in all studied genomes, whereas ArcA sites have been found in all Vibrionaceae and Pasteurellaceae, but not in the Yersinia spp. The regulation by NarP seems to be specific for the Pasteurellaceae. Orthologs for the nqr genes were not found in E. coli, but such orthologs were detected in Klebsiella pneumoniae and various Vibrionaceae and Pasteurellaceae [38–43]. On the other hand, E. coli has an H+-exporting NADH dehydrogenase enzyme, encoded by the nuo operon, whose expression is regulated by the NarL and Fnr transcription factors [44, 45]. No genes of the nuo operon demonstrate homology with the nqr genes. Orthologs of the nuo operon were found in the Yersinia genomes, but they were not preceded by candidate Fnr, ArcA or NarP binding sites. Thus, in the studied genomes, non-homologous displacement with a partial change of function leads to the sodium-dependent energetics used in conjunction with the proton-dependent one.

One more new regulog member is the dadAX operon. The first gene of this operon encodes the small subunit of respiratory D-amino acids dehydrogenase [46]. Candidate ArcA sites were detected in the Yersinia and Vibrionaceae genomes upstream of the dadAX operon. Thus, the use of D-amino acids as electron donors in some genomes may be controlled by ArcA.

An interesting example of taxon-specific regulation was observed for duplicated operons for trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) reductases and formate dehydrogenases. Two operons for TMAO reductases, torCAD and torYZ, were found in E. coli. [47, 48]. The torCAD expression is known to be repressed by the NarL protein and activated by the transcriptional factor TorR [49, 50], whereas torYZ is transcribed at a constant low level [47]. In the three Pasteurellaceae genomes, where the torCAD genes are absent, candidate sites for all three studied regulators were found upstream of the torYZ operon. In the Vibrionaceae genomes, the torCAD transcription is likely controlled by Fnr, whereas the torYZ expression seems to be regulated by NarP (see Table 1).

A similar situation was observed in E. coli for two formate dehydrogenase operons: the fdn operon is known to be regulated by the Fnr, NarL, and NarP proteins [51, 52], whereas the expression of the fdo operon is constant [53]. Previously Fnr binding site was predicted upstream of the formate reductase operon in Y. pestis [27]. Careful analysis of the phylogenetical trees for the Fdn and Fdo proteins (additional file 3) revealed that both Yersinia spp. contain fdo but lack fdn genes. In both Yersinia spp. expression of the fdo operon is regulated by all three studied regulators. Further, regulation was predicted for the fdhD gene whose product is essential for the formation of the Fdn and Fdo protein complexes [54]. Accordingly, candidate regulatory sites upatream of fdhD were found only in genomes containing the fdo or fdn operon.

Central metabolism and fermentation

Previously, respiration-dependent regulation of some genes involved in the central metabolism was studied in experiment [5, 55, 56] and computationally [27, 28]. Here, candidate regulatory sites were observed upstream of some more genes involved in the glycolysis, the gluconeogenesis, the pentose phosphate pathway, and the pyruvate and lactate metabolism: sfcA, ppsA, pckA, eno, pgk, talB and aldB. Unexpectedly, in the Pasteurellaceae, candidate NarP binding sites were found upstream of operons for glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and citrate cycle enzymes, such as eno, pgk, mdh and sucABCD (see Table 1).

Metabolism of carbohydrates

Regulation of sugar metabolism genes by the three considered regulators has not been shown experimentally. Here, conserved candidate sites for Fnr, ArcA or NarP were found upstream of some operons involved in the metabolism of various sugars. This is not surprising: indeed, the sugar metabolism is closely related to the central metabolism and sugars provide substrates for the energy production [57]. In particular, candidate sites were observed upstream of the operons ptsHI-crr and mtlADR (glucose- and mannitol-specific phosphotransferase systems, respectively [58]), deoCABD (degradation of pyrimidine deoxynucleosydes via deoxyribose-phosphates to acetaldehyde and glycerol-3-phosphate [59]), nagB (glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase [60]), gntXY (gluconate transport system [61]), malQ (amylomaltase [62]), and glgBXCAP (glycogen biosynthesis and catabolism [63]).

An unusual situation was observed for the glg genes. According to criteria described in "Methods", these genes were assigned to a single operon in the Yersinia spp. In the Pasteurellaceae, the glg genes are preceded by the malQ gene that belongs to the candidate malQ-glgBXCAP operon. In both Yersinia spp., candidate Fnr sites were found upstream of the glgB gene, whereas in the Pasteurellaceae, Fnr and NarP sites were found upstream of the malQ gene. Site conservation despite operon reorganization shows that the regulation of the glg genes by respiratory factors is important for the bacterial cell.

However, the degree of conservation of candidate sites for the carbohydrate metabolism genes is relatively low compared to genes from other groups, the observed sites are often taxon-specific, and there are almost no cases of double or triple combinations. This also is not surprising, since regulation of carbohydrate transport and catabolism is extremely flexible and fast-evolving (O.Laikova, personal communication). On the other hand, each individual predictions should be considered as preliminary.

Fatty acids metabolism

The regulation of operons involved in the fatty acids metabolism was not described previously, although there were some indirect indications to the existence of such regulation [27, 64]. Some of these operons have conserved binding sites and thus are likely to be regulated.

The homologous fabBA and fadIJ operons encode protein complexes for beta-oxidation of fatty acids. The FadBA protein complex is used in the fatty acids degradation in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, whereas FadIJ is used predominantly during anaerobiosis [64, 65]. Previously an effect of the arcA mutation on the fadBA operon expression was observed, although direct regulation was not shown [13]. Here, conserved candidate sites for Fnr and/or ArcA were found upstream of both these operons (Table 1).

The regulation was also predicted for the fadD, acpP-fabF, and fadL operons involved in the fatty acids metabolism and transport.

There are two possible explanations for the regulation of the fatty acids metabolism by the respiratory regulators. First, the fatty acids metabolism is closely related to the central metabolism, for example, through acetyl-CoA [66, 67]. Second, different enzymes for the fatty acids oxydation are preferred under aerobic and anaerobic conditions [64].

Nucleotide reductases

Fnr is known to activate the nrdDG operon in E. coli under anaerobiosis, whereas expression of one more operon encoding nucleotide reductase, nrdAB, is uneffected by the Fnr protein in E. coli [68]. This situation is conserved in the Yersinia spp. and the Vibrionaceae. In contrast, in the Pasteurellaceae, candidate Fnr sites were found upstream of the nrdAB operon. However, in H. ducreyi, where the nrdDG operon is absent, no candidate sites were found upstream of nrdAB. So, the overall picture seems to be that at least one nucleotide reductase operon must be transcribed constantly.

Transport

Previously, regulation by at least one of the studied regulators was shown experimentally for a number of E. coli transporter operons, see references in Table 1. Here, we identified additional transporters in the studied regulogs and demonstrated changes in the regulatory interactions.

Previously regulation of dicarboxylate transporters genes dcuA, dcuB and dcuC was shown for E.coli (see references in Table 1). However, in other gamma-proteobacteria the regulation of these genes may be different. Thus, the regulation of the dcuA and dcuB genes is typical for the Yersinia spp. and Pasteurellaceae, whereas in Vibrionaceae the regulation was observed for dcuC.

Regulators of transcription

Prediction of regulation of genes encoding different transcription factors seems to be one of the most interesting results of this study. Previously, the fnr, arcA, narP, and narQ genes were shown to be regulated by respiratory regulators in E. coli (see references in Table 1).

Fis is one of the most abundant DNA architectural proteins. It regulates supercoiling of bacterial DNA [69]. Experimentally it was shown that, in E. coli, Fis together with Fnr and/or ArcA regulates expression of the nrf [70], nir [71], ndh [72], adhE [73], yfiD [74], sdhCDAB-sucABCD [75], acnB [76], and narK [77] operons. In E. coli, the fis gene is cotranscribed with dusB [78] and the structure of the dusB-fis locus is conserved in all studied genomes. In the Pasteurellaceae, candidate Fnr and ArcA sites were found upstream of the dusB gene. Thus, in these genomes fis transcription is likely to be controlled by the respiratory regulators. Since Fis participates in the control of expression of respiration genes, it is possible that Fnr and ArcA regulate expression of the fis gene to optimize the transcription control of these genes.

The cpxRA operon encodes a two-component regulatory system involved in the environmental stress response [79]. Some data point to cross-interactions between the CpxR-CpxA and ArcA-ArcB systems in E. coli [80]. In the Pasteurellaceae, conserved Fnr and ArcA sites were detected upstream of the cpx operon.

OxyR is the transcriptional factor for the oxidative stress response [81]. In all Pasteurellaceae, candidate ArcA sites were observed upstream of oxyR gene. Since ArcA is active as a transcription factor only in the absence of the oxygen, it may be possible that in these conditions it represses the transcription of the unneeded oxygen sensor gene oxyR. However, the regulatory logic in this case is not absolutely clear.

In the Pasteurellaceae, conserved Fnr sites were found upstrean of the fur gene, whereas in the Vibrionaceae, the fur gene has candidate sites for ArcA. The observation that the Fur protein, ferric uptake regulator [82], is controlled by the respiratory regulators is not unexpected, because iron is an obligatory component of most respiratory complexes [2] and the transcriptional factor Fnr itself [83].

Other members of regulogs

In addition to the regulogs members described above, some genes were assigned to regulogs based on the formal criterion (see "Methods"), although their relevance to the respiration and central metabolism is not obvious. These genes and the candidate Fnr, ArcA, and NarP sites are shown in additional files 4 and 5. Although in the absence of a functional link, these predictions are somewhat weaker then the ones in the previous sections, we belive that they still warrant experimental verification.

Divergons and false-positive predictions

In some cases we found sites in intergenic regions between two genes forming divergons. In such cases it is not immediately clear, which of the two divergently transcribed operons is regulated. These divergent operon pairs are fadR/nhaB-dsbB in most studied genomes, yfiC/brnQ, torD/torR, and yhdWXYZ/VV12702 in the Vibrionaceae, and fkpA/slyX in the Yersinia spp. and the Pasteurellaceae. The data about candidate sites upstream of divergent genes are present in additional file 5.

In other cases candidate regulog members in divergons were dismissed, as functional analysis made it clear which of two divergent operons was regulated. This category includes the argR, ung, nfo and potABCD operons (additional file 6).

Discussion

Composition of regulogs in different families

The above analysis shows that regulation often differs between bacterial families. To assess the relative role of each studied regulator in different families, we calculated the number of genes and operons belonging to each regulog in each studied family. As expected, the composition of regulogs turned out to be quite diverse.

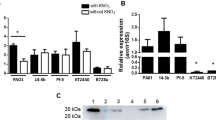

For example, in the Yersinia spp., the NarP regulog is significantly smaller than in other studied families (Figure 1a). It is not surprising, given that in these bacteria the nitrate- and nitrite-respiration system is strongly reduced, and only nitrate, but not nitrite, is used as an electron acceptor [24]. Accordingly, in these organisms, the nitrate respiration plays a less prominent role, and the nitrate-sensing system also is less important as compared to other studied genomes.

In contrast, in Pasteurellaceae, the NarP regulog is somewhat enlarged in comparison with the other two taxons. One more feature of this group is the increased overlap between regulogs. For example, conserved sites for both Fnr and NarP regulators were found upstream of 13 operons containing 53 genes (Figure 1b).

In the Vibrionaceae, the ArcA regulog is extended as compared to the other groups. In this family, conserved ArcA sites were found upstream of 47 operons containing 99 genes (Figure 1c).

Regulatory cascades

Group-specific regulatory cascades were predicted based on candidate sites upstream of the fnr, arcA, and narP genes.

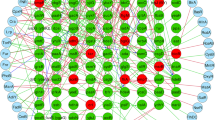

In E. coli, such cascades were analyzed experimentally (Figure 2a) [6, 7, 84]. There, the Fnr protein is the main regulator of the respiration that controls expression of genes for other regulators. Fnr represses transcription of the narXL operon [6] and regulates expression of the arcA gene [7]. Moreover, the fnr gene is autoregulated [6]. The arcA gene was predicted to be positively autoregulated [28]. The regulators of the nitrate and nitrate respiration, in turn, form a complicated regulatory network, where NarL activates expression of the narXL, narP and narQ operons, and NarP, in turn, activates the narXL transcription [84].

Respiration regulatory cascades in gamma-proteobacteria. (a) E. coli; (b) Yersinia spp.; (c) Pasteurellaceae; (d) Vibrionaceae. Experimentally determined regulation is shown by continuous arrows: green, activation; red, repression; blue, ambivalent regulation. Predicted regulation is shown by broken arrows: green, activation; black, type of regulation is not determined. Dotted arrows in (c): sites were not found in H. ducreyi.

However, this situation is not conserved in the genomes of other gamma-proteobacteria. In the Yersinia spp., Fnr apparently regulates the arcA expression and both fnr and arcA genes are autoregulated (Figure 2b). No regulatory sites were found upstream of the narP and narX genes. Thus, in the Yersinia spp., Fnr is the main regulator of respiration, similarly to E. coli. However, unlike the situation in the latter, in the Yersinia spp., the nitrate- and nitrite-responsive regulatory system does not participate in the regulatory cascades.

Even more remarkable changes in the regulatory cascades were observed in the Pasteurellaceae. In most of these genomes, candidate sites for Fnr, ArcA and NarP were found upstream of the fnr gene (Figure 2c), whereas no conserved regulatory sites were observed for the arcA and narP genes. This suggests that in this family the role of Fnr in the regulatory cascades decreases in comparison with E. coli. Minor differences were seen in H. ducreyi, where no NarP sites were found upstream of the fnr gene (Figure 2c).

In the Vibrionaceae, autoregulation for all regulator genes, fnr, arcA and narP, was observed. The ArcA protein also seems to regulate the narP gene, whereas Fnr controls the expression of the arcA and narP genes (Figure 2d). Thus, in these organisms, Fnr again is the main respiration regulator, but the role of ArcA in the regulatory cascades is increased as compared to E. coli.

Thus, the E.coli pattern of regulatory cascades is not conserved in other gamma-proteobacteria, and the relative role of each regulator in the regulatory cascades differs between families. When more genomes become available, it might be possible to describe the evolution of this regulatory system in more detail.

Family-specific regulatory interactions

In addition to differences in the regulatory cacades, there are major differences in the functional content of the respiration regulogs. These data are summarized in Figures 3, 4, 5.

Enterobacteriaceae (Yersinia spp.)

Two genomes of the Yersinia spp. were selected for this study because of the presence of a single regulator of the nitrate and nitrite respiration regulator NarP. These bacteria demonstrate a number of features that distinguish them from both E. coli and the two other studied families (Figure 3).

Most of these features relate to the nitrate and nitrite respiration. First of all, regulation is mediated by the unusual pair NarX-NarP, in contrast to other bacteria that have the pair NarQ-NarP (for details see below).

Another feature of the Yersinia spp. regulation is simplification of the regulatory cascades (see above). In comparison with E. coli, only the Fnr-ArcA cascade is conserved, whereas nitrate and nitrite responsive proteins seem to be excluded from cascades. This has an effect on the NarP regulog: in the respiration subsystem, candidate sites were found only upstream of genes essential for the nitrate respiration using formate as an electron donor (nap, ccm, fdo, fdhD), and upstream of the nir operon, whose products protect the cell from the toxic nitrite.

On the contrary, the Fnr and ArcA regulogs seemed to be quite similar to the corresponding regulogs in other studied genomes.

Pasteurellaceae

These bacteria demonstrate considerable changes in the regulatory cascade structure (see above). In the organisms from this group, Fnr loses the role of the main regulator.

A conspicious feature is the absence of orthologs for the ArcA-activating sensor ArcB (data not shown). Such situation was observed in another gamma-proteobacterium, Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 [85]. It is possible that the role of the ArcA-activating protein is played by CpxA that is homologous to ArcB. Regulation of the cpxRA operon by Fnr and ArcA also points to this possibility.

A specific feature of the Pasteurellaceae is also the existence of downstream cascades, as several transcription factor-encoding genes, cpxRA, fis, oxyR and fur, are preceded by conserved candidate sites. All of these operons, except fur, have no candidate sites in other studied genomes. One possible explanation might be that drastic re-structuring of the regulatory cascades during evolution of the Pasteurellaceae required additional fine tuning of the respiratory metabolism.

The increased role of the NarP transcriptional factor in the regulatory cascades is consistent with the expansion of the NarP regulog (Figure 4). This expansion is realized in different ways. For example, upstream of the cyd and nqr operons, NarP sites emerged in addition to the existing Fnr and ArcA ones. In the case of the mdh, eno and suc operons, we observe a change in the regulatory interactions, where NarP candidate sites appear instead of Fnr of ArcA sites seen in other families. Finally, NarP sites upstream of the eno and talB genes appear in the Pasteurellaceae, while there are no sites for the studied factors in other genomes.

Vibrionaceae

In these genomes, the Fnr role as the main regulator is conserved, but the role of the ArcA in the regulatory cascades slightly increases.

Again, this agrees with the expansion of the ArcA regulog, as there appear ArcA sites upstream of genes of central metabolism (Figure 5). Conserved candidate ArcA binding sites were also found upstream of other genes (additional file 4).

Ten analyzed representatives of gamma-proteobacteria occupy different ecological niches: H. ducreyi is an obligate pathogen [86], Y. pestis, Y. enterocolitica, P. multocida, A. actinomycetemcomitans, H. influenzae, V. vulnificus, V. parahaemolyticus and V. cholerae are facultative pathogens [87–94], and V. fischeri is a squid symbiont [95]. However, there are no obvious links between the bacterial lifestyle and specific regulatory interactions or regulog composition.

Variability of the nitrate and nitrite responsive regulatory system

Comparison of three global transcription regulators, Fnr, ArcA and NarP, demonstrates that the NarP-dependent regulation is the most flexible.

As we could not construct a NarL-site recognition rule, we considered only genomes containing NarP but not NarL. In all these genomes, the cytoplasmic nitrate respiratory system is absent and all reactions for the reduction of nitrate through nitrite to ammonium must occur in the periplasm. For this purpose, the proteins encoded by nap, ccm and nrf are sufficient. On the other hand, the genes for the cytoplasmic nitrate reduction, narGHJI and narK, are absent. In some studied genomes, the Yersinia spp. and most of the Vibrionaceae, the nir operon also is conserved [24]. This operon is used for the cytoplasmic nitrite reduction to ammonium, neutralizing toxic nitrite and providing ammonium as a substrate for the nitrogen assimilation [2]. Without the use of the cytoplasmic nitrite reduction, there is no need to select between the more effective, but also more dangerous, nitrate reduction in the cytoplasm, and the less effective but safer periplasmic reduction. Thus, all studied organisms do not require duplicated two-component regulatory systems and use the single pair NarP-NarQ.

In the Yersinia spp., an unusual sensor-regulator pair, NarX-NarP, was observed (additional file 7) [24]. However, in these genomes the sensor protein lacks the cysteine cluster typical for NarX from other species [23, 24]. Thus, we can suppose that NarX from Yersinia spp. acts as NarQ.

Another interesting result was the observation of conserved candidate NarP sites upstream of genes for aerobic respiration, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and citrate cycle, mdh, eno, pgk, sucABCD and nqr in Pasteurellaceae, and cydAB in the Pasteurellaceae and the Vibrionaceae. Regulation of genes for the aerobic metabolism by NarQ-NarP system may be explained by the fact that the NarQ sensor protein is sensitive to aeration [96].

Conclusion

Previously the regulation of respiration in the gamma-proteobacteria was well studied only in Escherichia coli and two experimental approaches prevailed. The first one was studying the regulation of a particular operon by multiple factors. The second approach was the analysis of multiple genes controlled by a specific regulatory system in one genome. With sequencing of complete genomes and development of comparative genomic methods, extensive analysis of a complex regulatory system in multiple genomes has become possible.

Here we applied a comparative genomic technique to the analysis of global regulation of respiration in numerous gamma-proteobacterial genomes. We analyzed three structurally different but functionally related regulatory systems.

One of the advantages of the applied technique is the possibility to study genomes for which no experimental data are available. It also allows one to find new members of regulons and to detect taxon-specific features of regulation. Thus, the saturation of the taxonomic space by complete genome sequences increases the opportunities for the application of comparative genomics.

In this article and supplementary materials we present the data about candidate sites, both conserved and non-conserved, in multiple genomes. These data are interesting from the point of view of evolution and also may be of use for experimental biology. At that, prediction of the specific sites upstream of particular operons facilitates the work of experimentalist in finding new members of regulons.

In the particular case of the respiration regulation, we were able to predict not only taxon-specific members of regulons, but also taxon-specific changes in regulatory cascades. We demonstrated considerable changes of regulatory interactions in different families and relative stability of the metabolic and regulatory systems taken as a whole. Similar observations were made in studies of dissimilatory metabolism of nitrogen oxides [97], iron homeostasis [98] and nitrogen fixation (work in progress). Overall, existence of a stable system core, re-wiring of regulatory cascades accompanied by shuffling of the regulators, and existence of taxon-specific periphery seem to be common features of all complex regulatory systems. At present, it is not clear what drives these changes. We have observed a correlation between the regulon size and the position of a regulator in regulatory cascades: regulators with larger regulons tend to occupy top positions in cascaeds, and thus re-wiring of cascades is accompanied with extension of regulons. On the other hand, there is no obvious link to differences in the species' lifestyles, metabolic capabilities, etc.

Methods

Genomes

Respiration was studied in ten genomes of organisms from three bacterial families:

Enterobacteriaceae (Yersinia pestis KIM, YP; Yersinia enterocolitica type 0:8, YE), Pasteurellaceae (Pasteurella multocida Pm70, PM; Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans HK1651, AA; Haemophilus influenzae Rd, HI; Haemophilus ducreyi 35000H, HD), and Vibrionaceae (Vibrio vulnificus CMCP6, VV; Vibrio parahaemolyticus RIMD 2210633, VP; Vibrio cholerae O1, VC; Vibrio fischeri ES114, VF). All studied organisms contain FNR, ArcA and NarP, but lack NarL.

The complete genome sequences of Y. pestis [99], P. multocida [100], H. influenzae [101], H. ducreyi [GenBank:AE017143], V. vulnificus [102], V. parahaemolyticus [103], V. cholerae [104], and V. fischeri [105] were downloaded from the GenBank database [106]. The complete sequence of Y. enterocolitica was taken from the Sanger Institute web site [107]. The complete sequence of A. actinomycetemcomitans was taken from the University of Oklahoma's Advanced Center for Genome Technology web site [108].

Comparative genomics of family-specific regulation

To describe three interacting regulatory systems, comparative genomic approaches were used [109]. Candidate sites were identified in upstream regions of annotated genes, including hypothetical ones. A gene was considered a putative member of a regulog (a group of regulated orthologs) [110], if it had an upstream candidate site in several genomes. Site search was performed in gene upstream regions, -500 to +100 nucleotides relative to the gene start, excluding coding regions of upstream genes. The recognition profiles (nucleotide weight matrices) [109] for Fnr [27], ArcA [28] and NarP [24] were described previously. The recognition profiles and sequence logos are shown in additional files 8 and 9, respectively.

The cutoff profile scores for ArcA and FNR sites were set using known E. coli sites from the dpinteract database [111]. All E. coli FNR-binding sites passed the threshold 3.75, and all E. coli ArcA binding sites, but one outlier (upstream of the gene pflA), scored above the used threshold 4.00. With these parameters about 600 genes per genome had candidate sites in upstream regions. The cutoff for candidate NarP binding sites (3.50) was defined as the minimum score of candidate NarP sites upstream of the nitrate and nitrite respiration genes (nap, nrf and ccm) in all studied genomes. This cutoff produced about 300 genes per genome.

Clearly, most candidate sites at this stage were false positives, but the threshold could not be made stricter without loss of true sites. Anyhow, after the filtration procedure described below the number of candidate regulog members significantly decreased. Only few genes with no obvious functional link to the studied systems remained, and in most cases this was caused by sites occurring upstream of divergently transcribed genes. These observations demonstrate that the filtration procedure seems to be sufficiently effective to remove most false positives. On the other hand, each individual prediction should be considered as preliminary. Another caveat is that "orphan" sites (species-specific sites upstream of genes not regulated by other considered factors) cannot be identified by the applied procedure.

Possible operon structure was taken into account as follows. Genes were assumed to belong to one operon if (i) they were transcribed in the same direction, (ii) the intergenic distances did not exceed 200 nucleotides, and (iii) two previous conditions were met in genomes from different families. These conditions are known to perform well in operon prediction [111].

As the regulation of respiration had not been experimentally analyzed in any of the studied organisms, we developed a technique based on exhaustive pairwise comparison of genomes within taxonomic groups. For the Pasteurellaceae and the Vibrionaceae, a gene was assigned to a regulog if candidate regulatory sites were found upstream of an operon containing this gene in at least three genomes of organisms from the same family. For the Yersinia spp., a gene was considered to be a member of a regulog if candidate sites were found in both Y. pestis and Y. enterocolitica genomes. Such sites were called "conserved sites". Sites that did not satisfy these requirements were called "nonconserved". Further, if a site for one regulator was found upstream of a particular gene in one taxon, we searched for sites for all three regulators upstream of this gene and its orthologs in all studied genomes.

This approach allowed us to find new members of regulogs and to describe taxon-specific features of regulation. Its limitation is that it allows one to detect only the fact of regulation but, due to the absence of mapped promoters in the studied genomes, does not predict the type of regulation, such as repression or activation.

Programs

The search for candidate sites was done using Genome Explorer [112]. Orthologs were determined as pairs of best bi-directional hits [113] identified by Genome Explorer [112]. Multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic trees were done using ClustalX [114]. Search for homologs of studied genes in sequence databases was done using the BLAST program [115] with E-value cutoff e-20.

References

Unden G, Bongaerts J: Alternative respiratory pathways of Escherichia coli: energetics and transcriptional regulation in response to electron acceptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997, 1320: 217-234. 10.1016/S0005-2728(97)00034-0.

Gennis RB, Stewart V: Respiration. Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Cellular and Molecular Biology 1. Edited by: Neidhart FC. 1996, Washington: ASM Press, 217-286.

Lazazzera BA, Beinert H, Khoroshilova N, Kennedy MC, Kiley PJ: DNA binding and dimerization of the Fe-S-containing FNR protein from Escherichia coli are regulated by oxygen. J Biol Chem. 1996, 27: 2762-2768.

Kiley PJ, Beinert H: Oxygen sensing by the global regulator, FNR: the role of the iron-sulfur cluster. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1999, 22: 341-352. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00375.x.

Lynch AS, Lin CC: Responses to molecular oxygen. Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Cellular and Molecular Biology 1. Edited by: Neidhart FC. 1996, Washington: ASM Press, 1526-1537.

Takahashi K, Hattori T, Nakanishi T, Nohno T, Fujita N, Ishihama A, Taniguchi S: Repression of in vitro transcription of the Escherichia coli fnr and narX genes by FNR protein. FEBS Lett. 1996, 340: 59-64. 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80173-8.

Compan I, Touati D: Anaerobic activation of arcA transcription in Escherichia coli: roles of Fnr and ArcA. Mol Microbiol. 1994, 11: 955-964. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00374.x.

Georgellis D, Kwon O, Lin EC: Quinones as the redox signal for the arc two-component system of bacteria. Science. 2001, 292: 2314-2316. 10.1126/science.1059361.

Malpica R, Franco B, Rodriguez C, Kwon O, Georgellis D: Identification of a quinone-sensitive redox switch in the ArcB sensor kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004, 101: 11318-11323. 10.1073/pnas.0403064101.

Toro-Roman A, Mack TR, Stock AM: Structural analysis and solution studies of the activated regulatory domain of the response regulator ArcA: a symmetric dimer mediated by the alpha4-beta5-alpha5 face. J Mol Biol. 2005, 349: 11-26. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.059.

Jeon Y, Lee YS, Han JS, Kim JB, Hwang DS: Multimerization of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated ArcA is necessary for the response regulator function of the Arc two-component signal transduction system. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276: 40873-40879. 10.1074/jbc.M104855200.

Lynch AS, Lin EC: Transcriptional control mediated by the ArcA two-component response regulator protein of Escherichia coli: characterization of DNA binding at target promoters. J Bacteriol. 1996, 178: 6238-6249.

Iuchi S, Lin EC: arcA (dye), a global regulatory gene in Escherichia coli mediating repression of enzymes in aerobic pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988, 85: 1888-1892. 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1888.

Unden G, Becker S, Bongaerts J, Holighaus G, Schirawski J, Six S: O2-sensing and O2-dependent gene regulation in facultatively anaerobic bacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1995, 164: 81-90.

Darwin AJ, Tyson KL, Busby SJ, Stewart V: Differential regulation by the homologous response regulators NarL and NarP of Escherichia coli K-12 depends on DNA binding site arrangement. Mol Microbiol. 1997, 25: 583-595. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4971855.x.

Rabin RS, Stewart V: Dual response regulators (NarL and NarP) interact with dual sensors (NarX and NarQ) to control nitrate- and nitrite-regulated gene expression in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1993, 175: 3259-3268.

Williams SB, Stewart V: Discrimination between structurally related ligands nitrate and nitrite controls autokinase activity of the NarX transmembrane signal transducer of Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Microbiol. 1997, 26: 911-925. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6262002.x.

Chiang RC, Cavicchioli R, Gunsalus RP: 'Locked-on' and 'locked-off' signal transduction mutations in the periplasmic domain of the Escherichia coli NarQ and NarX sensors affect nitrate- and nitrite-dependent regulation by NarL and NarP. Mol Microbiol. 1997, 24: 1049-1060. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4131779.x.

Darwin AJ, Li J, Stewart V: Analysis of nitrate regulatory protein NarL-binding sites in the fdnG and narG operon control regions of Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Microbiol. 1996, 20: 621-632. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5491074.x.

Li J, Kustu S, Stewart V: In vitro interaction of nitrate-responsive regulatory protein NarL with DNA target sequences in the fdnG, narG, narK and frdA operon control regions of Escherichia coli K-12. J Mol Biol. 1994, 241: 150-165. 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1485.

Stewart V, Bledsoe PJ: Synthetic lac operator substitutions for studying the nitrate- and nitrite-responsive NarX-NarL and NarQ-NarP two-component regulatory systems of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 2003, 185: 2104-2111. 10.1128/JB.185.7.2104-2111.2003.

Stewart V: Nitrate respiration in relation to facultative metabolism in enterobacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1988, 52: 190-232.

Stewart V: Biochemical society special lecture. Nitrate- and nitrite-responsive sensors NarX and NarQ of proteobacteria. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003, 31: 1-10.

Ravcheev DA, Rakhmaninova AB, Mironov AA, Gelfand MS: Regulation of nitrate and nitrite respiration in gammaproteobacteria: a comparative genomics study. Mol Biol (Mosk). 2005, 39: 832-846.

Stewart V, Bledsoe PJ: Fnr-, NarP- and NarL-dependent regulation of transcription initiation from the Haemophilus influenzae Rd napF(Periplasmic Nitrate Reductase). J Bacteriol. 2005, 187: 6928-6935. 10.1128/JB.187.20.6928-6935.2005.

Raghunathan A, Price ND, Galperin MY, Makarova KS, Purvine S, Picone AF, Cherny T, Xie T, Reilly TJ, Munson RJr, Tyler RE, Akerley BJ, Smith AL, Palsson BO, Kolker E: In silico metabolic model and protein expression of Haemophilus influenzae strain Rd KW20 in rich medium. OMICS. 2004, 8: 25-41. 10.1089/153623104773547471.

Gerasimova AV, Rodionov DA, Mironov AA, Gel'fand MS: Computer analysis of regulatory signals in bacterial genomes. Fnr binding segments. Mol Biol (Mosk). 2001, 35: 1001-1009.

Favorov AV, Gelfand MS, Gerasimova AV, Ravcheev DA, Mironov AA, Makeev VJ: A Gibbs sampler for identification of symmetrically structured, spaced DNA motifs with improved estimation of the signal length. Bioinformatics. 2005, 21: 2240-2245. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti336.

Baikalov I, Schroder I, Kaczor-Grzeskowiak M, Grzeskowiak K, Gunsalus RP, Dickerson RE: Structure of the Escherichia coli response regulator NarL. Biochemistry. 1996, 35: 11053-11061. 10.1021/bi960919o.

Baikalov I, Schroder I, Kaczor-Grzeskowiak M, Cascio D, Gunsalus RP, Dickerson RE: NarL dimerization? Suggestive evidence from a new crystal form. Biochemistry. 1998, 37: 3665-3676. 10.1021/bi972365a.

Maris AE, Sawaya MR, Kaczor-Grzeskowiak M, Jarvis MR, Bearson SM, Kopka ML, Schroder I, Gunsalus RP, Dickerson RE: Dimerization allows DNA target site recognition by the NarL response regulator. Nat Struct Biol. 2002, 9: 771-778. 10.1038/nsb845.

Xiao G, Cole DL, Gunsalus RP, Sigman DS, Chen CH: Site-specific DNA cleavage of synthetic NarL sites by an engineered Escherichia coli NarL protein-1,10-phenanthroline cleaving agent. Protein Sci. 2002, 12: 2427-2436. 10.1110/ps.0212502.

Gerasimova AV, Gelfand MS, Makeev VY, Mironov AA, Favorov AV: ArcA regulator of gamma-proteobacteria: Identification of the binding signal and description of the regulon. Biophysics. 2003, 48: 21-25.

Nielsen J, Jorgensen BB, van Meyenburg KV, Hansen FG: The promoters of the atp operon of Escherichia coli K12. Mol Gen Genet. 1984, 193: 64-71. 10.1007/BF00327415.

Kasimoglu E, Park SJ, Malek J, Tseng CP, Gunsalus RP: Transcriptional regulation of the proton-translocating ATPase (atpIBEFHAGDC) operon of Escherichia coli: control by cell growth rate. J Bacteriol. 1996, 178: 5563-5567.

Salmon K, Hung SP, Mekjian K, Baldi P, Hatfield GW: Global gene expression profiling in Escherichia coli K12. The effects of oxygen availability and FNR. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278: 29837-29855. 10.1074/jbc.M213060200.

Salmon KA, Hung SP, Steffan NR, Krupp R, Baldi P, Hatfield GW, Gunsalus RP: Global gene expression profiling in Escherichia coli K12: The effects of oxygen availability and ArcA. J Biol Chem. 2005, 280: 15084-15096. 10.1074/jbc.M414030200.

Beattie P, Tan K, Bourne RM, Leach D, Rich PR, Ward FB: Cloning and sequencing of four structural genes for the Na+-translocating NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase of Vibrio alginolyticus. FEBS Lett. 1994, 356: 333-338. 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01275-X.

Hase CC, Mekalanos JJ: Effects of changes in membrane sodium flux on virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999, 96: 3183-3187. 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3183.

Hayashi M, Nakayama Y, Unemoto T: Recent progress in the Na(+)-translocating NADH-quinone reductase from the marine Vibrio alginolyticus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001, 1505: 37-44. 10.1016/S0005-2728(00)00275-9.

Hayashi M, Hirai K, Unemoto T: Sequencing and the alignment of structural genes in the nqr operon encoding the Na(+)-translocating NADH-quinone reductase from Vibrio alginolyticus. FEBS Lett. 1995, 363: 75-77. 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00283-F.

Hayashi M, Nakayama Y, Unemoto T: Existence of Na+-translocating NADH-quinone reductase in Haemophilus influenzae. FEBS Lett. 1996, 381: 174-176. 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00114-7.

Bertsova YV, Bogachev AV: The origin of the sodium-dependent NADH oxidation by the respiratory chain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. FEBS Lett. 2004, 563: 207-212. 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00312-6.

Bongaerts J, Zoske S, Weidner U, Unden G: Transcriptional regulation of the proton translocating NADH dehydrogenase genes (nuoA-N) of Escherichia coli by electron acceptors, electron donors and gene regulator. Mol Microbiol. 1995, 16: 521-534. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02416.x.

Stolpe S, Friedrich T: The Escherichia coli NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) is a primary proton pump but may be capable of secondary sodium antiport. J Biol Chem. 2004, 279: 18377-18383. 10.1074/jbc.M311242200.

Lobocka M, Hennig J, Wild J, Klopotowski T: Organization and expression of the Escherichia coli K-12 dad operon encoding the smaller subunit of D-amino acid dehydrogenase and the catabolic alanine racemase. J Bacteriol. 1994, 176: 1500-1510.

Gon S, Patte JC, Mejean V, Iobbi-Nivol C: The torYZ (yecK-bisZ) operon encodes a third respiratory trimethylamine N-oxide reductase in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2000, 182: 5779-5786. 10.1128/JB.182.20.5779-5786.2000.

Mejean V, Iobbi-Nivol C, Lepelletier M, Giordano G, Chippaux M, Pascal MC: TMAO anaerobic respiration in Escherichia coli: involvement of the tor operon. Mol Microbiol. 1994, 11: 1169-1179. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00393.x.

Iuchi S, Lin EC: The narL gene product activates the nitrate reductase operon and represses the fumarate reductase and trimethylamine N-oxide reductase operons in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987, 84: 3901-3905. 10.1073/pnas.84.11.3901.

Simon G, Mejean V, Jourlin C, Chippaux M, Pascal MC: The torR gene of Escherichia coli encodes a response regulator protein involved in the expression of the trimethylamine N-oxide reductase genes. J Bacteriol. 1994, 176: 5601-5606.

Wang H, Gunsalus RP: Coordinate regulation of the Escherichia coli formate dehydrogenase fdnGHI and fdhF genes in response to nitrate, nitrite, and formate: roles for NarL and NarP. J Bacteriol. 2003, 185: 5076-5085. 10.1128/JB.185.17.5076-5085.2003.

Li J, Stewart V: Localization of upstream sequence elements required for nitrate and anaerobic induction of fdn (formate dehydrogenase-N) operon expression in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1992, 174: 4935-4942.

Abaibou H, Pommier J, Benoit S, Giordano G, Mandrand-Berthelot MA: Expression and characterization of the Escherichia coli fdo locus and a possible physiological role for aerobic formate dehydrogenase. J Bacteriol. 1995, 177: 7141-7149.

Schlindwein C, Giordano G, Santini CL, Mandrand MA: Identification and expression of the Escherichia coli fdhD and fdhE genes, which are involved in the formation of respiratory formate dehydrogenase. J Bacteriol. 1990, 172: 6112-6121.

Shalel-Levanon S, San KY, Bennett GN: Effect of oxygen, and ArcA and FNR regulators on the expression of genes related to the electron transfer chain and the TCA cycle in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2005

Shalel-Levanon S, San KY, Bennett GN: Effect of ArcA and FNR on the expression of genes related to the oxygen regulation and the glycolysis pathway in Escherichia coli under microaerobic growth conditions. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005, 92: 147-159. 10.1002/bit.20583.

Saier MH, Ramseier TM, Reizer J: Regulation of carbon utilization. Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Cellular and Molecular Biology. 1. Edited by: Neidhart FC. 1996, Washington: ASM Press, 1325-1333.

Postma PW, Lengeler JW, Jacobson GR: Phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems. Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Cellular and molecular biology. Edited by: Neidhardt FC. 1996, Washington: ASM Press, 1149-1174.

Neughard J, Kelln RA: Biosynthesis and conversions of pyrimidines. Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Cellular and molecular biology. 1. Edited by: Neidhardt FC. 1990, Washington: ASM Press, 580-599.

Plumbridge JA, Cochet O, Souza JM, Altamirano MM, Calcagno ML, Badet B: Coordinated regulation of amino sugar-synthesizing and -degrading enzymes in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1993, 175: 4951-4956.

Porco A, Alonso G, Isturiz T: The gluconate high affinity transport of GntI in Escherichia coli involves a multicomponent complex system. J Basic Microbiol. 1998, 38: 395-404. 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4028(199811)38:5/6<395::AID-JOBM395>3.0.CO;2-7.

Decker K, Peist R, Reidl J, Kossmann M, Brand B, Boos W: Maltose and maltotriose can be formed endogenously in Escherichia coli from glucose and glucose-1-phosphate independently of enzymes of the maltose system. J Bacteriol. 1993, 175: 5655-5665.

Yang H, Liu MY, Romeo T: Coordinate genetic regulation of glycogen catabolism and biosynthesis in Escherichia coli via the CsrA gene product. J Bacteriol. 1996, 178: 1012-1017.

Campbell JW, Morgan-Kiss RM, Cronan JE: A new Escherichia coli metabolic competency: growth on fatty acids by a novel anaerobic beta-oxidation pathway. Mol Microbiol. 2003, 47: 793-805. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03341.x.

Clark DP, Cronan JE: Two-carbon compounds and fatty acids as carbon sources. Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Cellular and Molecular Biology. 1. Edited by: Neidhart FC. 1996, Washington: ASM Press, 343-357.

Cronan JE, Rock CO: Biosynthesis of membrane lipids. Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Cellular and molecular biology. 1. Edited by: Neidhardt FC. 1996, Washington: ASM Press, 612-636.

Lin ECC: Amino acids as carbon sources. Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Cellular and molecular biology. 1. Edited by: Neidhardt FC. 1996, Washington: ASM Press, 358-379.

Boston T, Atlung T: FNR-mediated oxygen-responsive regulation of the nrdDG operon of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2003, 185: 5310-5313. 10.1128/JB.185.17.5310-5313.2003.

Schneider R, Lurz R, Luder G, Tolksdorf C, Travers A, Muskhelishvili G: An architectural role of the Escherichia coli chromatin protein FIS in organising DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29: 5107-5114. 10.1093/nar/29.24.5107.

Browning DF, Grainger DC, Beatty CM, Wolfe AJ, Cole JA, Busby SJ: Integration of three signals at the Escherichia coli nrf promoter: a role for Fis protein in catabolite repression. Mol Microbiol. 2005, 57: 496-510. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04701.x.

Browning DF, Cole JA, Busby SJ: Transcription activation by remodelling of a nucleoprotein assembly: the role of NarL at the FNR-dependent Escherichia coli nir promoter. Mol Microbiol. 2004, 53: 203-215. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04104.x.

Jackson L, Blake T, Green J: Regulation of ndh expression in Escherichia coli by Fis. Microbiology. 2004, 150: 407-413. 10.1099/mic.0.26869-0.

Membrillo-Hernandez J, Lin EC: Regulation of expression of the adhE gene, encoding ethanol oxidoreductase in Escherichia coli: transcription from a downstream promoter and regulation by fnr and RpoS. J Bacteriol. 1999, 181: 7571-7579.

Green J, Baldwin ML, Richardson J: Downregulation of Escherichia coli yfiD expression by FNR occupying a site at -93.5 involves the AR1-containing face of FNR. Mol Microbiol. 1998, 29: 1113-1123. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01002.x.

Cunningham L, Guest JR: Transcription and transcript processing in the sdhCDAB-sucABCD operon of Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 1998, 144: 2113-2123.

Cunningham L, Gruer MJ, Guest JR: Transcriptional regulation of the aconitase genes (acnA and acnB) of Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 1997, 143: 3795-3805.

Kolesnikow T, Schroder I, Gunsalus RP: Regulation of narK gene expression in Escherichia coli in response to anaerobiosis, nitrate, iron, and molybdenum. J Bacteriol. 1992, 174: 7104-71011.

Ninnemann O, Koch C, Kahmann R: The E.coli fis promoter is subject to stringent control and autoregulation. EMBO J. 1992, 11: 1075-1083.

Raivio TL: Envelope stress responses and Gram-negative bacterial pathogenesis. Mol Microbiol. 2005, 56: 1119-1128. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04625.x.

Iuchi S, Furlong D, Lin EC: Differentiation of arcA, arcB, and cpxA mutant phenotypes of Escherichia coli by sex pilus formation and enzyme regulation. J Bacteriol. 1989, 171: 2889-2893.

Christman MF, Storz G, Ames BN: OxyR, a positive regulator of hydrogen peroxide-inducible genes in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium, is homologous to a family of bacterial regulatory proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989, 86: 3484-3488. 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3484.

Bagg A, Neilands JB: Ferric uptake regulation protein acts as a repressor, employing iron (II) as a cofactor to bind the operator of an iron transport operon in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1987, 26: 5471-5477. 10.1021/bi00391a039.

Sutton VR, Mettert EL, Beinert H, Kiley PJ: Kinetic analysis of the oxidative conversion of the [4Fe-4S]2+ cluster of FNR to a [2Fe-2S]2+ cluster. J Bacteriol. 2004, 186: 8018-8025. 10.1128/JB.186.23.8018-8025.2004.

Darwin AJ, Stewart V: Expression of the narX, narL, narP, and narQ genes of Escherichia coli K-12: regulation of the regulators. J Bacteriol. 1995, 177: 3865-3869.

Gralnick JA, Brown CT, Newman DK: Anaerobic regulation by an atypical Arc system in Shewanella oneidensis. Mol Microbiol. 2005, 56: 1347-1357. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04628.x.

Wood GE, Dutro SM, Totten PA: Haemophilus ducreyi inhibits phagocytosis by U-937 cells, a human macrophage-like cell line. Infect Immun. 2001, 69: 4726-4733. 10.1128/IAI.69.8.4726-4733.2001.

Sebbane F, Lemaitre N, Sturdevant DE, Rebeil R, Virtaneva K, Porcella SF, Hinnebusch BJ: Adaptive response of Yersinia pestis to extracellular effectors of innate immunity during bubonic plague. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006, 103: 11766-11771. 10.1073/pnas.0601182103.

Orth JH, Lang S, Aktories K: Action of Pasteurella multocida toxin depends on the helical domain of Gαq. J Biol Chem. 2004, 279: 34150-34155. 10.1074/jbc.M405353200.

Rohde JR, Luan XS, Rohde H, Foxm JM, Minnich SA: The Yersinia enterocolitica pYV virulence plasmid contains multiple intrinsic DNA bends which melt at 37 degrees C. J Bacteriol. 1999, 181: 4198-4204.

de Haar SF, Hiemstra PS, van Steenbergen MT, Everts V, Beertsen W: Role of polymorphonuclear leukocyte-derived serine proteinases in defense against Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect Immun. 2006, 9: 5284-5291. 10.1128/IAI.02016-05.

Bayliss CD, Sweetman WA, Moxon ER: Mutations in Haemophilus influenzae mismatch repair genes increase mutation rates of dinucleotide repeat tracts but not dinucleotide repeat-driven pilin phase variation rates. J Bacteriol. 2004, 186: 2928-2935. 10.1128/JB.186.10.2928-2935.2004.

Amaro C, Biosca EG, Fouz B, Alcaide E, Esteve C: Evidence that water transmits Vibrio vulnificus biotype 2 infections to eels. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995, 61: 1133-1137.

Sizemore RK, Colwell RR, Tubiash HS, Lovelace TE: Bacterial flora of the hemolymph of the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus: numerical taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1975, 29: 393-399.

Rivera IN, Chun J, Huq A, Sack RB, Colwell RR: Genotypes associated with virulence in environmental isolates of Vibrio cholerae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001, 67: 2421-2429. 10.1128/AEM.67.6.2421-2429.2001.

Nyholm SV, McFall-Ngai MJ: The winnowing: establishing the squid-vibrio symbiosis. Nat Rev Microbial. 2004, 2: 632-642. 10.1038/nrmicro957.

Stewart V, Chen LL, Wu HC: Response to culture aeration mediated by the nitrate and nitrite sensor NarQ of Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Microbiol. 2003, 50: 1391-1399. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03776.x.

Rodionov DA, Dubchak IL, Arkin AP, Alm EJ, Gelfand MS: Dissimilatory metabolism of nitrogen oxides in bacteria: comparative reconstruction of transcriptional networks. PLoS Comput Biol. 2005, 1: e55-10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010055.

Rodionov DA, Gelfand MS, Todd JD, Curson AR, Johnston AW: Comparative reconstruction of transcriptional network controlling iron and manganese homeostasis in alpha-proteobacteria. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006, 2: e163-10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020163.

Deng W, Burland V, Plunkett G, Boutin A, Mayhew GF, Liss P, Perna NT, Rose DJ, Mau B, Zhou S, Schwartz DC, Fetherston JD, Lindler LE, Brubaker RR, Plano GV, Straley SC, McDonough KA, Nilles ML, Matson JS, Blattner FR, Perry RD: Genome sequence of Yersinia pestis KIM. J Bacteriol. 2002, 184: 4601-4611. 10.1128/JB.184.16.4601-4611.2002.

May BJ, Zhang Q, Li LL, Paustian ML, Whittam TS, Kapur V: Complete genomic sequence of Pasteurella multocida, Pm70. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001, 98: 3460-3465. 10.1073/pnas.051634598.

Fleischmann RD, Adams MD, White O, Clayton RA, Kirkness EF, Kerlavage AR, Bult CJ, Tomb JF, Dougherty BA, Merrick JM, McKenney K, Sutton GG, FitzHugh W, Fields CA, Gocayne JD, Scott JD, Shirley R, Liu LI, Glodek A, Kelley JM, Weidman JF, Phillips CA, Spriggs T, Hedblom E, Cotton MD, Utterback T, Hanna MC, Nguyen DT, Saudek DM, Brandon RC, Fine LD, Fritchman JL, Fuhrmann JL, Geoghagen NS, Gnehm CL, McDonald LA, Small KV, Fraser CM, Smith HO, Venter JC: Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995, 269: 496-512. 10.1126/science.7542800.

Kim YR, Lee SE, Kim CM, Kim SY, Shin EK, Shin DH, Chung SS, Choy HE, Progulske-Fox A, Hillman JD, Handfield M, Rhee JH: Characterization and pathogenic significance of Vibrio vulnificus antigens preferentially expressed in septicemic patients. Infect Immun. 2003, 71: 5461-5471. 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5461-5471.2003.

Makino K, Oshima K, Kurokawa K, Yokoyama K, Uda T, Tagomori K, Iijima Y, Najima M, Nakano M, Yamashita A, Kubota YKSYT, Honda T, Shinagawa H, Hattori M, Iida T: Genome sequence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a pathogenic mechanism distinct from that of V. cholerae. Lancet. 2003, 361: 743-749. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12659-1.

Heidelberg JF, Eisen JA, Nelson WC, Clayton RA, Gwinn ML, Dodson RJ, Haft DH, Hickey EK, Peterson JD, Umayam LA, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Read TD, Tettelin H, Richardson D, Ermolaeva MD, Vamathevan J, Bass S, Qin H, Dragoi I, Sellers P, McDonald L, Utterback T, Fleishmann RD, Nierman WC, White O, Salzberg SL, Smith HO, Colwell RR, Mekalanos JJ, Venter JC, Fraser CM: DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature. 2000, 406: 477-483. 10.1038/35020000.

Ruby EG, Urbanowski M, Campbell J, Dunn A, Faini M, Gunsalus R, Lostroh P, Lupp C, McCann J, Millikan D, Schaefer A, Stabb E, Stevens A, Visick K, Whistler C, Greenberg EP: Complete genome sequence of Vibrio fischeri: A symbiotic bacterium with pathogenic congeners. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005, 102: 3004-3009. 10.1073/pnas.0409900102.

GenBank Overview. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank]

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. [http://www.sanger.ac.uk]

The University of Oklahoma's Advanced Center for Genome Technology. [http://www.genome.ou.edu]

Gelfand MS, Koonin EV, Mironov AA: Prediction of transcription regulatory sites in Archaea by a comparative genomic approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28: 695-705. 10.1093/nar/28.3.695.

Alkema WB, Lenhard B, Wasserman WW: Regulog analysis: detection of conserved regulatory networks across bacteria: application to Staphylococcus aureus. Genome Res. 2004, 14: 1362-1373. 10.1101/gr.2242604.

DPInteract. [http://arep.med.harvard.edu/dpinteract]

Mironov AA, Vinokurova NP, Gel'fand MS: Software for analyzing bacterial genomes. Mol Biol (Mosk). 2000, 34: 253-262.

Tatusov RJ, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ: A genomic perspective on protein families. Science. 1997, 278: 631-637. 10.1126/science.278.5338.631.

Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG: The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25: 4876-4882. 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876.

Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ: Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25: 3389-3402. 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Alexandra B. Rakhmaninova, Alexander Favorov, Olga Laikova and Dmitry Rodionov for useful discussions.

This study was supported by grants from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (55005610), the Russian Academy of Science (Program "Molecular and Cellular Biology"), the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (04-04-49361), and INTAS (05-8028).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Authors' contributions

AAM and MSG designed and coordinated the project. DAR and AVG carried out the genome analysis. DAR and MSG drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Dmitry A Ravcheev, Anna V Gerasimova contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

12864_2006_767_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional File 1: Predicted regulatory interactions. For genome abbreviations see "Methods". Candidate sites are shown by letters: F – Fnr sites; A – ArcA sites, N – NarP sites; conserved sites are shown by capital letters, non-conserved ones by lower-case letters (for details see "Methods"). Absence of sites is shown by dashes. Absent genes are shown by zeros. Cases when the operon structure is not conserved are denoted by superscripts, and the structures of the corresponding operons are described in detail in additional file 2 using the matching superscripts. (PDF 98 KB)

12864_2006_767_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Additional File 2: Observed changes in the operon structures. For genome abbreviations see "Methods". The superscripts correspond to the superscripts in additional file 1. (PDF 95 KB)

12864_2006_767_MOESM3_ESM.pdf

Additional File 3: Phylogenetic trees for FdnG/FdoG (a), FdnH/FdoH (b) and FdnI/FdoI. The trees were constructed by the neighbour-joining method. The expected fraction of amino acid substitutions is indicated for branches longer than 0.05. Genome abbreviations: EC – Escherichia coli, ST – Salmonella typhi, EO – Erwinia carotovora, YP – Yersinia pestis, YE – Y. enterocolitica, PM – Pasteurella multocida, AA – Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, HI – Haemophilus influenzae. The analysis of the trees indicates that the most parsimonious evolutionary scenario is the duplication of the fumarate dehydrogenase operon in the ancestral Enterobacteria and further species-specific loss of the Fdn copy in the Yersinia lineage. In any case, it is clear that the fumarate dehydrogenase of the Yersinia spp. is Fdo. (PDF 292 KB)

12864_2006_767_MOESM4_ESM.pdf

Additional File 4: Additional predicted regulatory interactions. "For genome abbreviations see "Methods". Candidate sites are shown by letters: F – Fnr sites, A – ArcA sites, N – NarP sites; conserved sites are shown by capital letters, non-conserved ones, by lower-case letters (for details see "Methods"). Absence of the corresponding sites is shown by dashes. Absent genes are shown by zeros. Superscripts point to changes in operon structures described in detail in additional file 5. #: operon forms a divergon with an another one." (PDF 301 KB)

12864_2006_767_MOESM5_ESM.pdf

Additional File 5: Additional observed changes in the operon structures. For genome abbreviations see "Methods". Superscripts coincide with the corresponding superscripts in additional file 4. (PDF 99 KB)

12864_2006_767_MOESM6_ESM.pdf

Additional File 6: False-positive predictions. The last column lists the reasons to exclude the operons. For genome abbreviations see "Methods". (PDF 49 KB)

12864_2006_767_MOESM7_ESM.pdf

Additional File 7: Phylogenetic trees for NarL/NarP (a) and NarX/NarQ (b). The trees were constructed by the neighbour-joining method. The expected fraction of amino acid substitutions is indicated for brances. The branches corresponding to Yersinia spp. proteins are shown with broken lines. Genome abbreviations: EC – Escherichia coli, ST – Salmonella typhi, EO – Erwinia carotovora, YP – Yersinia pestis, YE – Y. enterocolitica, PM – Pasteurella multocida, AA – Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, HI – Haemophilus influenzae, HD – Haemophilus ducreyi, VV – Vibrio vulnificus, VP – V. parahaemolyticus, VC – V. cholerae, VF – Vibrio fischeri. (PDF 681 KB)

12864_2006_767_MOESM8_ESM.pdf

Additional File 8: Position weight matrices (profiles) for Fnr (a), ArcA (b) and NarP (c) binding sites. Rows: nucleotides. Columns: Positions. Cells: positional nucleotide weights. (PDF 466 KB)

12864_2006_767_MOESM9_ESM.pdf

Additional File 9: Sequence logos for the Fnr (a), ArcA (b) and NarP (c) binding sites. Horizontal axis, position in the binding site; vertical axis, information content in bits. The height of each column is proportional to the positional information content in the given position; the height of each individual symbol reflects its prevalence in the given position. (PDF 227 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ravcheev, D.A., Gerasimova, A.V., Mironov, A.A. et al. Comparative genomic analysis of regulation of anaerobic respiration in ten genomes from three families of gamma-proteobacteria (Enterobacteriaceae, Pasteurellaceae, Vibrionaceae). BMC Genomics 8, 54 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-8-54

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-8-54