Abstract

Background

We have developed and fabricated a salmonid microarray containing cDNAs representing 16,006 genes. The genes spotted on the array have been stringently selected from Atlantic salmon and rainbow trout expressed sequence tag (EST) databases. The EST databases presently contain over 300,000 sequences from over 175 salmonid cDNA libraries derived from a wide variety of tissues and different developmental stages. In order to evaluate the utility of the microarray, a number of hybridization techniques and screening methods have been developed and tested.

Results

We have analyzed and evaluated the utility of a microarray containing 16,006 (16K) salmonid cDNAs in a variety of potential experimental settings. We quantified the amount of transcriptome binding that occurred in cross-species, organ complexity and intraspecific variation hybridization studies. We also developed a methodology to rapidly identify and confirm the contents of a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) library containing Atlantic salmon genomic DNA.

Conclusion

We validate and demonstrate the usefulness of the 16K microarray over a wide range of teleosts, even for transcriptome targets from species distantly related to salmonids. We show the potential of the use of the microarray in a variety of experimental settings through hybridization studies that examine the binding of targets derived from different organs and tissues. Intraspecific variation in transcriptome expression is evaluated and discussed. Finally, BAC hybridizations are demonstrated as a rapid and accurate means to identify gene content.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Atlantic salmon are part of the Salmonidae family which comprise all salmon, trout, whitefish, grayling, and charr. A tremendous amount of basic biology is already known about salmonids from studies carried out on their physiology, population dynamics, behavioural ecology and phylogenetics [1]. Salmon also provide an excellent model system in which to study fundamental genetic mechanisms of growth, development, reproduction and response to infection and disease. For example, salmonids serve as prominent models for studies involving environmental toxicology [2], carcinogenesis [3], comparative immunology [4], the molecular genetics and physiology of the stress response [5], olfaction [6], vision [7], osmoregulation [8], growth [9] and gametogenesis [10].

Answers to fundamental scientific questions can also be gained from the study of salmonid genomes. The ancestor of all extant salmonids underwent a whole genome duplication and after a series of subsequent genetic events, salmon are now considered to be pseudo-tetraploid. How a genome reorganizes itself to cope with a duplicated genome and the importance of gene duplications for evolution and adaptation are long standing issues that remain unresolved. Questions regarding the origins of genomes have direct implication for our understanding of the roles of gene families, duplication and deletion of segments of genomes, and the mutational process in human health and disease. They also provide a foundation for understanding the genome of Atlantic salmon to benefit conservation and enhancement of wild stocks, aquaculture and environmental assessments. Genomic resources enable us to address fundamental scientific questions concerning the evolution of salmonid genomes, and the expression of genes and proteins in a wide variety of natural and altered environments and conditions.

Toward these goals, more than 175 cDNA libraries have been constructed from a wide variety of tissues and different developmental stages and more than 300,000 salmonid cDNA sequence reads have been combined from a consortium comprising groups from Canada (Ben Koop et al. and the Genomics Research on Atlantic Salmon Project (GRASP); Susan Douglas et al. and the Institute for Marine Biosciences, NRC); France (Yann Guiguen et al. and INRA-SCRIBE); Norway (Bjorn Hoyheim et al. and the Norwegian School of Veterinary Science (NSVS)) and the U.S.A. (Caird Rexroad III and the USDA/ARS National Center for Cool and Cold Water Aquaculture). These sequences were assembled into over 40,000 unique contigs. A preliminary microarray of 3,557 cDNAs was constructed and assessed on its' ability to provide new data in the study of cellular and tissue responses to pollutants, diseases and stress, as well as for reproduction and development [11–15]. On the basis of these results, a larger array of 16,006 genes has been constructed and initial results have shown sensitivity of gene expression patterns to disease challenge, and to small environmental and physiological changes [16].

Results and discussion

Library construction (directional cloning by 5'Eco RI, 3'Xho I in pBluescript II XR, Stratagene; or TOPO TA cloning of suppression subtractive hybridization PCR products, Invitrogen and Clontech) and subsequent EST sequencing (using M13 forward primer) were designed to generate 3'-end sequences to enable us to distinguish between potential paralogs arising from the recent salmonid genome duplication. We have determined from a weighted average measurement comparing four different directionally-cloned library types (such as non-normalized versus normalized libraries) that approximately 9% of inserts are in the reverse orientation and therefore yield 5' sequence with the M13 forward primer [11]. The GRASP 3'-end reads were used as a framework on which to build the contigs from additional data provided by the NRC, INRA, USDA/ARS and the NSVS. Part of the evaluation process for selecting genes for the microarray required criteria that would guard against chimeras. Simply put, this meant that each gene choice had to be part of a contig with multiple distinct clones covering each region, or that it was sufficiently similar to another sequence across its whole length that it was unlikely to be chimeric. We did select for immune-specific and reproduction-relevant genes for the microarray, but the preponderance of ESTs on the 16K chip were randomly picked based on EST cluster quality and uniqueness and therefore represent a wide variety of different classes of genes.

Application of a 16K cDNA microarray to different species

To explore the validity of using the 16K microarray with other fish species, the 13,421 Atlantic salmon (AS) and 2,576 rainbow trout (RT) cDNA features were interrogated with labeled liver targets from four members of the order Salmoniformes (AS, RT, chinook salmon and lake whitefish) and one member of the order Osmeriformes (rainbow smelt) (Table 1). The average percentage binding of AS, RT, chinook salmon, lake whitefish (LW) and rainbow smelt liver targets to the 16K chip was 54.0%, 63.3%, 51.0%, 50.6% and 30.1%, respectively. The average percentage of targets bound to AS and RT features for each species are also shown (Table 1).

Our study indicates that there are no significant differences in the percent of targets that bound to the 16K microarray for the four salmonids examined (AS, RT, chinook and LW). There is a similar hybridization performance for all salmonids. However, RT targets do consistently show higher overall binding to the microarray; the reason for this efficiency is not yet clear.

The hybridization performance of the rainbow smelt targets were roughly one-half those of the salmonid cDNAs. Of the species contributing targets to our heterologous hybridization experiment, the osmerid targets were the most phylogenetically removed from the salmonid features. Indeed, a recent mitogenomic study places the Osmeroidei in a separate clade from the Salmoniformes [17]. These two clades are separated by at least 200 MY with the Salmonidae having undergone at least one genome duplication event since their divergence [18, 19]. Other factors such as genome gene content (ie., numbers of paralogs) and genome size are likely to be factors affecting the overall degree of hybridization [11].

Application of a 16K cDNA microarray to different tissues

Different tissues and organs exhibit differences in transcriptome complexity, depending on their cellular heterogeneity and differentiated specializations. The mRNAs of a typical somatic cell are divided into three classes based on their sequence complexity and diversity [20]. The most prevalent class consists of only a few mRNA species that comprise the abundant transcripts present in a cell. Often these transcripts are dedicated to cellular functions common to all tissues, but they usually represent genes that specify an organs' unique function. The high complexity class of mRNAs includes thousands (perhaps millions) of different mRNA species, each represented by fewer than 15 copies per cell [20].

However, it should be noted that some subsets of genes that have been thought to be unique to one organ have been found to be expressed in others. This has been demonstrated for transcripts in the brain-gonad axis, and is probably not exclusive to these organs. For example, mammalian pheromone/odorant receptors and specific piscine hormones and receptors of the brain are also expressed in the gonad [12, 21, 22]. To date, the biological functions of these transcripts in the gonad have not been determined, raising intriguing questions regarding multiplicity of functions for complex transcripts, even in diploid vertebrates such as mammals.

To determine the differences in the transcriptome complexity of seven different AS tissues and organs, the 13,421 AS and 2,576 RT cDNA features were hybridized with labeled targets from midgut, brain, spleen, muscle, ovary, kidney and testis (Table 2). The average percentage binding of midgut, brain, spleen, muscle, ovary, kidney and testis targets to the 16K chip was 64.4%, 54.7%, 54.6%, 52.8%, 51.0%, 49.7% and 30.2%, respectively. In general, about 45% of the salmonid microarray features were not bound by targets from the various AS tissues and organs.

Application of a 16K cDNA microarray to the same tissue from cohorts

To determine the amount of gene expression variability that exists between individuals of a single species, we compared the transcriptomes of livers from three fish with identical histories. We compared the average percent of variation (or scatter) in expression of liver transcripts between cohorts 1 and 2 (liverpairs 1/2), cohorts 1 and 3 (liverpairs 1/3) and cohorts 2 and 3 (liverpairs 2/3). Two separate experiments of six hybridizations each were conducted with each liverpairing having one dye-flip.

Examining each individual array in the intraspecies study showed that the overall mean scatter was 12.6% (Table 3). When the liverpair arrays and their respective dye-flips were combined and averaged, the overall mean scatter was reduced to 9.7%. This indicates that systematic unequal dye incorporation exists resulting in high scatter values. This dye bias has been well-documented by other researchers [23–25] and illustrates the importance of incorporating dye swap pairs when performing microarray hybridizations whenever possible. The overall mean scatter was further reduced to 5.2% when the analysis included technical dye swap replicates between respective liverpairs (Table 3). This demonstrates that increasing the number of technical replicates in a microarray experiment is an important factor to consider for reducing random scatter. It is encouraging that the overall scatter between individuals from the same broodstock was quite low. Thus technical and biological variability across arrays and individuals can be significantly reduced by the investigator if the appropriate experimental design is employed.

Application of a 16K cDNA microarray to analyze BAC contents

To assess the use of the 16K array as a screening tool to identify the genes present in a salmonid BAC, the 13,421 AS and 2,576 RT features were interrogated with nebulized and labeled fragments from a single BAC whose sequence has been determined (Table 4). Analysis of our initial BAC hybridizations revealed that a high proportion of transposon-like sequences and long and short interspersed nuclear elements were binding to the array. It is known that many different repeat elements derived from once-mobile transposable segments comprise large portions of the Atlantic salmon genome [26–29]. In an effort to improve the specificity of target binding to the microarray for BAC hybridization, we employed a Cot-1 DNA protocol to reduce the binding of these repetitive elements (Table 4). The addition of Cot-1 DNA increased the number of expected genes identified and the number of hits for the expected genes by displacing many of the repeat family and transposon associated elements.

Although Cot-1 DNA did improve the ability to identify genes for the BAC we examined, Cot-1 DNA alone is not enough to block the complications that arise from repetitive elements in whole genome hybridizations. In preliminary comparative genomic hybridization studies we have found that even with Cot-1 DNA included in the hybridizations, the repetitive DNA segments found in salmonid genomes interfere with the interpretation of the data. Most investigators are not interested in these repetitive segments, but rather in the genes that are interspersed between them. Moreover, we have found that often these repetitive elements lead to false positives. Using other methods, such as including repeat-element amplified products with Cot DNA, as well as higher stringency washes, might improve binding specificities. We are currently working on various strategies to maximize blocking of this repeat element 'noise'.

Conclusion

We validate and demonstrate the usefulness of the 16K microarray over a wide range of teleosts, even for transcriptome targets distantly removed from salmonids phylogenetically. We show the potential of the use of the microarray in a variety of experimental settings through hybridization studies that examine the binding of targets derived from different organs and tissues. Intraspecific variation in transcriptome expression is evaluated and discussed. Finally, BAC hybridizations are demonstrated as a rapid and accurate means to identify gene content. We expect that this array will serve as an important resource for genetic, physiological, ecological and many other fields of salmonid study.

Methods

Gene selection

cDNA library construction, recombinant plasmid preparation and extraction, sequencing, sequence analysis and contig assembly for the GRASP have been described previously in detail [11–13]. Selection criteria for unique Atlantic salmon (AS) and rainbow trout (RT) cDNAs for inclusion on the 16K microarray were as follows: ESTs (cDNA fragments) were assembled into contiguous sequences (contigs) by PHRAP [30] under stringent assembly parameters (minimum overlap score:100; repeat stringency: 0.99). Contig consensus sequences and singleton sequences were aligned with non-redundant GenBank nucleotide and amino acid sequence databases using BLASTN and BLASTX, respectively [31, 32]. Threshold for a significant BLAST hit was set at E = 1e-15.

It was determined that a contig must contain at least one "usable" sequence, where "usable" was a)- the sequence must be 3' (with high probability; containing polyA signal or having been sequenced with an oligo-dT primer or being at the 3'-end of a contig, with orientation determined by a strong hit against a protein in GenBank's non-redundant protein database), b)- be a sequence stretch containing more than 400 bp, and c)- the sequence must be at least 95% similar to the consensus of the contig.

It was also determined that if a contig was a singleton or singleton-equivalent (where all sequences were from the same plate or library thus not providing sufficient evidence for non-chimera status), then the contig selection was reinforced either by a)- a significant BLAST hit, E<1e-15 (BLASTN or BLASTX), or b)- it having 94% (or more) identity with a homolog (either paralog or ortholog) covering at least 400 nucleotides. If the contig was a non-singleton, it was determined that it must be a)- one "block" (having no regions in the interior of the contig covered by only one sequence, to decrease probability of chimeras), and b)- of high enough overall quality (with an overall score > 95% positions without conflicts, weighted by number of sequences which support the consensus) and c)- have few leading and trailing singleton positions (no more than 25%), since such positions make it a de facto singleton.

Approximately 3,500 additional sequences were selected with the following criteria: a)- no chosen contig could have 94% or more identity with another chosen contig, and b)- tentative consensus sequences (TC) identified by TIGR [33] could be included. By these criteria, approximately 1000 clones were picked indiscriminately from both normalized AS and RT cDNA libraries, 800 clones were selected from suppression subtracted hybridization libraries and 700 sequences were added from requests of potential array users. Additionally, 949 non-overlapping sequences (856 AS, 93 RT) from clones included in the preliminary 3,557-gene chip (plus one T cell receptor beta) were selected. Finally, approximately 500 immune-specific genes were also chosen to bring the total number of genes represented on the chip to 16,006. In the 16,006 cDNA features there are 13,421 AS, 2,576 RT, 4 chinook salmon, 3 rainbow smelt and 2 LW representatives.

Gene identification

EST contigs were built using cDNAs on the array as reference and all ESTs currently in the GRASP database. Subsequent to microarray fabrication, the consensus sequences were screened for repeats using a custom salmonid repeat database with RepeatMasker. Masked consensus sequences were compared to GenBank databases. Using the stringent selection threshold above, the current percentage of the 16K features that are known and unknown genes is 55.8% and 44.2%, respectively. Analysis at less stringent thresholds is ongoing to identify all genes on the microarray.

Microarray fabrication

Clones were robotically rearrayed from daughter glycerol stock 384-well plates into 96-well plates pre-filled with 7% glycerol in LB + ampicillin, incubated overnight at 37°C, and checked for uniform optical density. Plasmid inserts were PCR amplified in a Tetrad PTC-200 thermocycler (MJ Research) using 1 ul overnight culture, 0.2 mM M13/pUC forward primer (5'-CCCAGTCACGACGTTGTAAAACG-3'), 0.2 mM M13/pUC reverse primer (5'-AGCGGATAACAATTTCACACAGG-3'), 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 250 mM dNTPs, 1U AmpliTaq (Perkin Elmer), and nuclease-free H2O (Gibco) to 100 ul. PCR conditions were: 2 min for 95°C; then 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 45 sec, 72°C for 3 min; followed by 72°C for 7 min. Five ul of each PCR product were run on a 1% agarose gel to assess yield and quality. PCR products were robotically cleaned (Qiagen) and consolidated into 384-well plates, lyophilized by speed-Vac, and resuspended in 20 ul 3X SSC. Each purified PCR product concentration was determined and diluted to give a final concentration of 400 ng/uL.

All cDNAs were printed as single spots on EZ Rays aminosilane slides (Matrix/Apogent Discoveries) with the Biorobotics Microgrid II microarray printer (Genomic Solutions). Microspot™ 10K quill pins (Biorobotics) in a 48 pin tool were used to deposit approximately 0.5 nl (0.2 ng cDNA) per spot onto the slide. The slides were crosslinked in a UV Stratalinker 2400 (Stratagene) at 300 mJ. The resulting microarrays have a 4-by-12 metagrid layout with 19 X19 spot subgrid, each spot having an approximate diameter and pitch of 100 um and 0.20 mm, respectively. A 280 bp GFP (green fluorescent protein) cDNA was amplified from a GFP clone (Clontech) using the primers (5'-GAAACATTCTTGGACACAAATTGG-3') and (5'-GCAGCTGTTACAAACTCAAGAAGG-3') and printed in each subgrid corner to assist in gridding.

Six exogenous genome (Arabidopsis) cDNAs were amplified from the following clones kindly provided by The Arabidopsis Information Resource: rubisco activase [GenBank:T41667], protochlorophyllide reductase precursor [GenBank:R30630], chlorophyll a/b-binding protein CP29 [GenBank:N65746], PSII oxygen-evolving complex protein 2 [GenBank:H36167], tonoplast intrinsic protein root-specific RB7 [GenBank:AA067532] and ferredoxin (2Fe_2S) precursor [GenBank:W43249]. The Arabidopsis cDNAs were spotted in quadruplicate on each microarray and used for thresholding (determining number of transcripts present). Also, a ubiquitin normalizer serially diluted (50 pg, 5 pg, 500 fg, 50 fg, 5 fg, 0.05 fg and 0.005 fg) was applied to the array. Spot morphology was assessed by visual inspection, SYBR® Green 1 (Molecular Probes) staining or hybridization with labeled non-specific probe. To check clone tracking, 47 high quality sequences were obtained from randomly-selected wells of the cleaned, consolidated 384-well plates used for microarray printing. Each tracked clone had BLAST identifiers matching gene IDs predicted from the re-array spreadsheet, indicating highly accurate clone tracking throughout the process of microarray fabrication.

Animals

Various tissues (brain, kidney, midgut, spleen, ovary, testis, muscle) were sampled from two three-year-old AS (S. salar) adults (Pacific Biological Station, Nanaimo, B.C.). Livers were obtained from several 2.5 year-old AS (McConnell strain) and chinook salmon (O. tshawytscha) subadults (Fisheries and Oceans Canada, West Vancouver, B.C.). RT (O. mykiss) tissues (Spring Valley Strain) were obtained from Mountain Trout Sales (Sooke, B.C.). LW (C. clupeaformis) livers were obtained from three-year-old animals (Laboratoire Bernatchez, Université Laval, Quebec) and rainbow smelt (Osmerus mordax) livers were obtained from adult smelt (NRC Institute for Marine Biosciences and Memorial University of Newfoundland). Each institution that provided tissue, raised and treated the fish in compliance with ethics committee or government body guidelines.

Tissue and RNA extraction

Fish were exsanguinated for several minutes. The tissues were removed and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until RNA extraction. Flash frozen tissues were ground using baked (220°C, 5 h) mortars and pestles under liquid N2, then total RNA was extracted in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). RNAs obtained from these preparations were used for generating labeled targets for microarray hybridizations.

Microarray hybridizations

The microarray experiments were designed to comply with MIAME guidelines [34]. To minimize technical variability, all targets were synthesized in one round and each hybridization experiment was conducted simultaneously on slides from a single batch where possible. Each hybridization experiment included dye-flips to compensate for cyanine fluor effects. Total RNA samples were quantified and quality-checked by spectrophotometer and agarose gel, respectively.

All hybridization experiments were performed using the SuperScript Indirect cDNA Labeling System kit and instructions (Invitrogen). Briefly, 5.0 ug total RNA was reverse transcribed using an anchored oligo d(T)20 primer in cDNA synthesis reactions that incorporated aminoallyl- and aminohexyl-modified nucleotides. The modified cDNAs were then labeled with fluorescent Cy5 or Cy3 dye in reactions with the amino-functional groups in coupling buffer.

BAC DNA preparation

Previously sequenced Atlantic salmon BAC 92I04 obtained from the Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute Atlantic Salmon BAC library (CHORI – 214) was isolated and purified. A total of 30 ug BAC DNA was added to shearing buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA and 20% glycerol. The DNA was sheared into fragments to a concentrated mass of 1500 bp by nebulization in an Invitrogen nebulizer (Cat# 45-0071) at 30 psi of N2 and concentrated by ethanol precipitation.

A total of 5 ug of nebulized BAC DNA was combined with 7.5 ug of pd(N)6 random hexamers (Amersham Biosciences), heated to 100°C for 5 minutes and then cooled on ice for 5 minutes. BAC fragment probes were then generated using Klenow Fragment DNA Polymerase (exo-) (New England Biolabs) in the presence of amino-modified nucleotides (Invitrogen) and labeled with fluorescent Cy3 dye in coupling buffer (see above). Before hybridizations, labeled BAC with Cot-1 salmon DNA was heated to 100°C for 15 minutes, placed on ice for 5 minutes, then warmed to 37°C; labeled BAC without Cot-1 salmon DNA was heated to 80°C for 10 minutes and then cooled to 65°C, before application of treated BAC to microarrays (see below).

Microarray preparation

All microarrays were prepared for hybridization by washing 2 X 5 min in 0.1% SDS, washing 5 X 1 min in MilliQ H2O, immersing 3 min in 95°C MilliQ H2O, and drying by centrifugation (5 min 2000 rpm in 50 ml conical tube). All slides were prehybridized in 5 X SSC, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% BSA for 1.5 h at 49°C. Arrays were briefly washed 2 X 20 sec in MilliQ H2O, then dried by centrifugation. Labeled DNAs were hybridized to prewarmed microarrays in a formamide based buffer (25% formamide, 4X SSC, 0.5% SDS, 2X Denhardt's solution) 16 h at 49°C. The arrays were washed 1 X 10 min in 49°C (2X SSC, 0.1% SDS), and then 2 X 5 min in (2X SSC, 0.1% SDS), 2 X 5 min in 1X SSC and 2 X 5 min in 0.1X SSC at room temperature, then dried by centrifugation.

Microarray analyses

Fluorescent images of hybridized arrays were acquired immediately at 10 um resolution using ScanArray Express (PerkinElmer). The Cy3 and Cy5 cyanine fluors were excited at 543 nm and 633 nm, respectively, at the same laser power (90%), with adjusted photomultiplier tube settings between slides to balance the Cy5 and Cy3 channels. Fluorescent intensity data was extracted from TIFF images using Imagene 5.5 software (Biodiscovery). Quality statistics were compiled in Excel from raw Imagene fluorescence intensity report files. Features were sorted (16,006 salmonid spots each representing different cDNAs; 24 Arabidopsis spots representing 6 different cDNAs) and median signal values and mean numbers of salmonid features passing threshold were determined for Cy3 and Cy5 data separately.

For cross-species and tissue-on-tissue experiments, the hybridization performance of labeled targets to salmonid features was assessed as a percentage of features bound from the numbers of AS and RT features passing a hybridization signal threshold, defined as two standard deviations above Arabidopsis signal mean. No transformations or normalizations were performed on these data. Only features deemed present by Imagene 5.6.1 (excluding marginal and absent values) were used for analyses. We also analyzed some of these data at two standard deviations above empty spot mean signal intensity and found that this was a less stringent method of thresholding (data not shown).

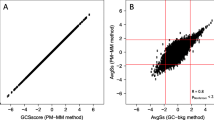

Intraspecific liver and BAC hybridization data analysis (background correction, Lowess normalization, and fold change gene list formation) was performed in GeneSpring 6.1 (Silicon Genetics). All scanned microarray TIFF images, extracted ImaGene grid files, the gene identification file and ImaGene quantified data files are available on-line as supplemental data [35]. The data is deposited in NCBI's GEO repository under PLATFORM GPL 2716 [36].

References

Thorgaard GH, Bailey GS, Williams D, Buhler DR, Kaattari SL, Ristow SS, Hansen JD, Winton JR, Bartholomew JL, Nagler JJ, Walsh PJ, Vijayan MM, Devlin RH, Hardy RW, Overturf KE, Young WP, Robison BD, Rexroad C, Palti Y: Status and opportunities for genomics research with rainbow trout. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2002, 133: 609-646. 10.1016/S1096-4959(02)00167-7.

Katchamart S, Miranda CL, Henderson MC, Pereira CB, Buhler DR: Effect of xenoestrogen exposure on the expression of cytochrome P450 isoforms in rainbow trout liver. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2002, 21: 2445-2451. 10.1897/1551-5028(2002)021<2445:EOXEOT>2.0.CO;2.

William DE, Bailey GS, Reddy A, Hendricks JD, Oganesian A, Orner GA, Pereira CB, Swenberg JA: The rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) tumor model:recent applications in low-dose exposures to tumor initiators and promoters. Toxicol Pathol. 2003, 31 (Suppl): 58-61.

Shum BP, Guethlein L, Flodin LR, Adkison MA, Hedrick RP, Nehring RB, Stet RJM, Secombes C, Parham P: Modes of salmonid MHC class I and II evolution differ from the primate paradigm. J Immunol. 2001, 166: 3297-3308.

Basu N, Todgham AE, Ackerman PA, Bibeau MR, Nakano K, Schulte PM, Iwama GK: Heat shock protein genes and their functional significance in fish. Gene. 2002, 295: 173-183. 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)00687-X.

Zhang C, Brown SB, Hara TJ: Biochemical and physiological evidence that bile acids produced and released by lake char (Salvelinus namaycush) function as chemical signals. J Comp Physiol [B]. 2001, 171: 161-171.

Faillace MP, Julian D, Korenbrot JI: Mitotic activation of proliferative cells in the inner nuclear layer of the mature fish retina: regulatory signals and molecular markers. J Comp Neurol. 2002, 451: 127-141. 10.1002/cne.10333.

Tipsmarck CK, Madsen SS, Seidelin M, Christensen AS, Cutler CP, Cramb G: Dynamics of Na(+), K(+), 2Cl(-) cotransporter and Na(+), K(+)-ATPase expression in the branchial epithelium of brown trout (Salmo trutta) and Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). J Exp Zool. 2002, 293: 106-118. 10.1002/jez.10118.

Devlin RH, Biagi CA, Yesaki TY, Smailus DE, Byatt JC: Growth of domesticated transgenic fish. Nature. 2001, 409: 781-782. 10.1038/35057314.

Madigou T, Uzbekova S, Lareyre JJ, Kah O: Two messenger RNA isoforms of the gonadotrophin-releasing hormone receptor, generated by alternative splicing and/or promoter usage, are differentially expressed in rainbow trout gonads during gametogenesis. Mol Reprod Dev. 2002, 63: 151-160. 10.1002/mrd.90006.

Rise ML, von Schalburg KR, Brown GD, Mawer MA, Devlin RH, Kuipers N, Busby M, Beetz-Sargent M, Alberto R, Gibbs AR, Hunt P, Shukin R, Zeznik JA, Nelson C, Jones SR, Smailus DE, Jones SJ, Schein JE, Marra MA, Butterfield YS, Stott JM, Ng SH, Davidson WS, Koop BF: Development and application of a salmonid EST database and cDNA microarray: data mining and interspecific hybridization characteristics. Genome Res. 2004, 14: 478-490. 10.1101/gr.1687304.

von Schalburg KR, Rise ML, Brown GD, Davidson WS, Koop BF: A comprehensive survey of the genes involved in maturation and development of the rainbow trout ovary. Biol Reprod. 2005, 72: 687-699. 10.1095/biolreprod.104.034967.

Rise ML, Jones SR, Brown GD, von Schalburg KR, Davidson WS, Koop BF: Microarray analyses identify molecular biomarkers of Atlantic salmon macrophage and hematopoietic kidney response to Piscirickettsia salmonis infection. Physiol Genomics. 2004, 20: 21-35. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00036.2004.

Abstract. [http://www.intl-pag.org/12/abstracts/P7a_PAG12_825.html]

Abstract. [http://abstracts.co.allenpress.com/pweb/setac2004/document/?ID=42585]

Abstract. [http://abstracts.co.allenpress.com/pweb/setac2004/document/?ID=42564]

Ishiguro NB, Miya M, Nishida M: Basal euteleostean relationships: a mitogenomic perspective on the phylogenetic reality of the " Protacanthopterygii". Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2003, 27: 476-488. 10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00418-9.

Allendorf FW, Thorgaard GH: Tetraploidy and the evolution of salmonid fishes. Evolutionary Genetics of Fishes. Edited by: Turner BJ. 1984, New York: Plenum Press, 1-53.

Ohno S, Wolf U, Atkin NB: Evolution from fish to mammals by gene duplication. Hereditas. 1968, 59: 169-187.

Gilbert SF: Control of development by RNA processing. Developmental Biology. 1988, Sinauer Associates, Inc. Sunderland, Massachusetts, 441-464. second

Kawasawa Y, McKenzie LM, Hill DP, Bono H, RIKEN GER Group and GSL Members, Yanagisawa M: G protein-coupled receptor genes in the FANTOM2 database. Genome Res. 2003, 13: 1466-1477. 10.1101/gr.1087603.

Kumar RS, Ijiri S, Kight K, Swanson P, Dittman A, Alok D, Zohar Y, Trant JM: Cloning and functional expression of a thyrotropin receptor from the gonads of a vertebrate (bony fish): potential thyroid-independent role for thyrotropin in reproduction. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000, 167: 1-9. 10.1016/S0303-7207(00)00304-X.

Yang YH, Dudoit S, Luu P, Lin DM, Peng V, Ngai J, Speed TP: Normalization for cDNA microarray data: a robust composite method addressing single and multiple slide systematic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30: e15-10.1093/nar/30.4.e15.

Jin W, Riley RM, Wolfinger RD, White KP, Passador-Gurgel G, Gibson G: The contribution of sex, genotype and age to transcriptional variance in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Genet. 2001, 29: 389-395. 10.1038/ng766.

Tseng GC, Oh MK, Rohlin L, Liao JC, Wong WH: Issues in cDNA microarray analysis: quality filtering, channel normalization, models of variations and assessment of gene effects. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29: 2549-2557. 10.1093/nar/29.12.2549.

Furano AV, Duvernell DD, Boissinot S: L1 (LINE-1) retrotransposon diversity differs dramatically between mammals and fish. Trends in Genetics. 2004, 20: 9-14. 10.1016/j.tig.2003.11.006.

Murata S, Takasaki N, Saitoh M, Okada N: Determination of the phylogenetic relationships among Pacific salmonids by using short interspersed elements (SINEs) as temporal landmarks of evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993, 90: 6995-6999.

Goodier JL, Davidson WS: Characterization of a repetitive element detected by NheI in the genomes of Salmo species. Genome. 1994, 37: 639-645.

Goodier JL, Davidson WS: Tc1 transposon-like sequences are widely distributed in salmonids. J Mol Biol. 1994, 241: 26-34. 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1470.

University of Washington Genome Centre. [http://www.genome.washington.edu/UWGC]

Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ: Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25: 3389-3402. 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ: Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990, 215: 403-410. 10.1006/jmbi.1990.9999.

The Institute for Genomic Research. [http://www.tigr.org]

Brazma A, Hingamp P, Quackenbush J, Sherlock G, Spellman P, Stoeckert C, Aach J, Ansorge W, Ball CA, Causton HC, Gaasterland T, Glenisson P, Holstege FC, Kim IF, Markowitz V, Matese JC, Parkinson H, Robinson A, Sarkans U, Schulze-Kremer S, Stewart J, Taylor R, Vilo J, Vingron M: Minimum information about a microarray experiment (MIAME)-toward standards for microarray data. Nat Genet. 2001, 29: 365-371. 10.1038/ng1201-365.

Genomics Research on Atlantic Salmon Project. [http://web.uvic.ca/cbr/grasp]

National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/geo/]

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Genome Canada, Genome BC, and the Province of BC, and additionally by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (BFK, WSD). We thank Jeff Zeznik, Bob Shukin and Bruce Dangerfield for microarray processing and printing (Array Facility, Prostate Centre, Vancouver General Hospital). We also would like to thank Robert Devlin, Dionne Sakhrani and Nicole Hofs (Fisheries and Oceans Canada, West Vancouver, B.C., CA) for chinook salmon and AS tissues; Simon Jones and Kim Taylor (Pacific Biological Station, Nanaimo, B.C., CA) for AS tissues; Jack and Kevin Nickolichuk (Mountain Trout Sales, Sooke, B.C., CA) for RT tissues; Robert Saint-Laurent (Laboratoire Bernatchez, University of Laval, Quebec, CA) for LW livers and Clayton Williams, Vanya Ewart (NRC Institute for Marine Biosciences, Nova Scotia, CA) and Connie Short (Ocean Sciences Center, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Newfoundland, CA) for rainbow smelt tissues.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

KRVS: co-creator of cDNA libraries; participated in coordination of project; performed organ complexity and intraspecific hybridization experiments; drafted the manuscript.

MLR: constructed and participated in the characterization of high-complexity cDNA libraries, and participated in the development of selection criteria for genes included on the 16006-gene microarray.

GAC: development and optimization of hybridization protocols; performed various species and BAC labeling hybridization experiments; data analysis for manuscript.

GDB: implemented the sequence processing pipeline (from screening and trimming reads to BLAST-identifying assembled contigs); contributed to the set of criteria for establishing that a read was not a chimera, and assisted in other computational aspects of the project.

ARG: contributed to gene selection and identification protocols and general informatics.

CCN: participated in the design and manufacture of the microarray.

WSD and BFK conceived of the study and supervised its design and coordination.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

von Schalburg, K.R., Rise, M.L., Cooper, G.A. et al. Fish and chips: Various methodologies demonstrate utility of a 16,006-gene salmonid microarray. BMC Genomics 6, 126 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-6-126

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-6-126