Abstract

Background

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized the detection of transcriptomic signatures due to its high-throughput sequencing ability. Therefore, genomic annotations on different animal species have been rapidly updated using information from tissue-enriched novel transcripts and novel exons.

Results

34 putative novel transcripts and 236 putative tissue-enriched exons were identified using RNA-Seq datasets representing six tissues available in mouse databases. RT-PCR results indicated that expression of 21 and 2 novel transcripts were enriched in testes and liver, respectively, while 31 of the 39 selected novel exons were detected in the testes or heart. The novel isoforms containing the identified novel exons exhibited more dominant expression than the known isoforms in heart and testes. We also identified an example of pathology-associated exclusion of heart-enriched novel exons such as Sorbs1 and Cluh during pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy.

Conclusion

The present study depicted tissue-enriched novel transcripts, a tissue-specific isoform switch, and pathology-associated alternative splicing in a mouse model, suggesting tissue-specific genomic diversity and plasticity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Information on the spatial and temporal signatures of transcriptomes is essential for diagnosis and treatment of severe diseases such as cardiomyopathies and malignant cancers. For the past several decades, high-throughput (HTP) data generated using the microarray method have contributed significantly to the discovery of quantitative signatures of various diseases. However, the microarray method has critical limitations, such as spatial bias, uneven probe problems, low sensitivity, and dependency on the probes spotted. Therefore, large-scale transcriptomic analyses using the microarray method have been superseded by the RNA-Seq generated through application of the recently developed next-generation sequencing (NGS) method.

RNA-Seq is a revolutionary method useful for transcriptomic signatures, since it can elucidate both quantitative and qualitative signatures (e.g., alternative splicing, AS) by de novo analysis, and it has therefore made possible the large-scale discovery of novel transcripts, such as noncoding RNAs. AS is an important event for proteome complexity and proteome diversity. However, current approaches using microarray or serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) tags have faced limitations, such as probe dependency and low coverage. The robust sequencing capacity of RNA-Seq has dramatically increased our knowledge of dynamic alternation via AS. For instance, RNA-seq has revealed the subtype-specific novel isoforms for the most common breast cancers (e.g. triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), non-TNBC, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive breast cancer [1]). Information related to novel exons, recognized in the intronic regions, has rapidly increased owing to RNA-Seq [2–4]. De novo analyses of RNA-Seq datasets have rapidly updated the genome annotations of different species through examination of novel transcripts [5–7]. Furthermore, the detection of novel non-coding RNAs by RNA-Seq has identified them as important functional molecules regulating various biological processes [8–10].

The present study employed RNA-seq data to identify novel exons and novel transcripts enriched in different tissues in mice (here “novel” means “new” exons or “new” transcripts not identified in mice so far), leading to the discovery of novel transcripts expressed in testes or liver, and recognition that the novel isoforms containing the novel exons were dominantly expressed in testes or heart. These results should contribute to a more sophisticated annotation of the mouse genome, as well as improved understanding of tissue-specific gene regulation.

Results and Discussion

In silico analysis of tissue-enriched novel transcripts and exons

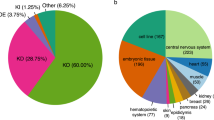

In order to identify tissue-enriched novel transcripts and exons in mice, the RNA-seq datasets for six tissues (i.e., GSE30352 for brain, cerebrum, heart, kidney, liver and testes) [11] were analyzed using the pipeline ‘Tophat-Cufflinks-Cuffcompare’ [12, 13]. As a result, 76,250 and 77,784 transcribed loci were constructed using UCSC and ENSEMBL, respectively. Among the transcribed loci, 184 transcripts located in the intergenic region were collected as putative novel transcripts (Additional file 1: Table S1). From this list of putative novel transcripts, we further examined the tissue-enriched transcripts using DESeq [14]. Novel transcripts exhibiting significant enrichment (P < 0.05) in the specific tissue were eventually defined as tissue-enriched novel transcripts. As a result, 32 and 2 novel transcripts were found to be significantly enriched in testes and liver, respectively (Table 1).

In addition to the novel transcripts, we examined the tissue-enriched novel exons for known genes and the novel junctions for the obtained de novo transcripts. In total, 5,582 novel exons were identified from 6 tissues (Additional file 2: Table S2). To examine tissue-enrichment of the novel exons, the read numbers for the novel exons were counted and compared across the 6 tissues in a pairwise manner using DESeq. Of the 236 novel exons evaluated, 197 were expressed in testes (Additional file 2: Table S2), which was consistent with a study by Howald et al. reporting that these novel transcripts are mainly identified in the testes of humans [15].

Experimental confirmation of testes- and liver-enriched novel transcripts

Enrichment of the putative novel transcripts in testes and liver was further examined experimentally using mouse heart, testes, liver, kidney, brain and lung tissues by qRT-PCR and RT-PCR, to determine the expression levels and patterns. Among the 32 testes- and 2 liver-enriched novel transcripts (32 tNT and 2 lNT), enrichment of 21 tNTs and 2 lNTs were experimentally confirmed (Figure 1). We were unable to detect 11 tNTs, including tNT-5, −31, and −32, by RT-PCR. Although highly specific expression of tNT-13 was found in testes using qRT-PCR, we could not detect the expression using RT-PCR, which may have been due to low expression levels.

Testes- and liver-enriched expression of the novel transcripts. The expressions of testes- and liver-enriched novel transcripts were experimentally confirmed by (A) RT-PCR and (B) qRT-PCR for 6 tissues (H: Heart, T: Testes, Lv: Liver, K: Kidney, B: Brain, Lu: Lung). tNT and lNT indicate testes- and liver-enriched novel transcripts, respectively. tNTs and lNTs with blue and orange circles, respectively, were experimentally confirmed by both RT-PCR and qRT-PCR experiments. Values on the X axis indicate the relative expression of tNTs and lNTs in testes and liver, respectively, compared to the expressions in brain (log10(2-△△Ct)). The values on the Y axis indicate the relative expression of the novel transcripts when compared to the expressions of 18S in testes (log10(2-△Ct)).

Expression levels of tNTs and lNTs were generally enriched in testes and liver (e.g. 8.3–1,328-fold higher than in the brain). However, the most specific expression in testes was observed in tNT-2 (1,328–3,502 fold higher than other tissues), a homolog to Slc9c2, which is a human Na+/H+ exchanger. tNT-7 was the most abundantly expressed of the tNTs (Figure 1B). No expressed sequence tag (EST) for tNT-7 has been reported to date, however, it is predicted to be homologous to cysteine-rich secretory protein (CRISP) involved in sperm-egg fusion [16]. Most of the tNTs encoding proteins with MW values ranging from 6–389 kDa exhibited a broad range of similarity (19–100%) between the species (Table 1). Despite the absence of a matched mouse gene or EST, tNT-1 was identical to the predicted protein model, XP_001475034.3, and shared high sequence identity with rat Slco6d1 (~80%), suggesting that it may function as an ion transporter in testes. tNT-18 seems to encode a protein identical to NP001028651.1 encoded by Gm1516 in chromosome 3. tNT-18 is located 3Mbps away from Gm1516 in chromosome 3, indicating that Gm1516 and tNT-18 are paralogs encoding the same protein sequence.

Many of these novel transcripts are predicted to encode functional domains or highly homologous proteins in other species, as well (Table 1). Conversely, two testes-enriched novel transcripts (tNT-10 and −22) likely represented noncoding transcripts. Noncoding transcripts are also important regulatory molecules involved in diverse processes such as gene-specific transcription [17], regulation of basal transcriptional machinery [18], splicing [19], and translation [20]. The in-depth functional characterization of the confirmed testes- and liver-enriched novel transcripts is expected to lead to important information regarding tissue-specific gene regulation.

Experimental confirmation of testes-enriched novel exons

Among 197 testis-enriched novel exons, 26 novel exons were selected for experimental validation, on the basis of their read number (expression level), easiness of primer design, and straightforward exon structures. Among the 26 testes-enriched novel exons (hereafter, tNE), the strong enrichment of 24 tNEs in testes was confirmed by qRT-PCR and RT-PCR (Figure 2A and B). tNE-17 of Ms4a5 was the most abundantly and specifically expressed in testes, whereas tNE-6 was barely expressed in testis. tNE-1, −13, −15 and −22 were strongly expressed in testes, whereas little or no expression was observed in other tissues. Multiple novel exons were identified for Eya4 (tNE-2, −12 and −26), Fam71d (tNE-4, −5 and −7) and Pkm2 (tNE-10 and −21). We further examined the expression of the genes containing tNEs to determine whether the expression was due to testes-specific genes. Results indicated that most of the genes containing tNEs were ubiquitously expressed in different tissues (Figure 2C and D). However, the expressions of genes such as Skp2, Eya4, Scamp2, and Zfp385a were significantly lower in testes than in the brain (Figure 2D), despite strong expression of the tNEs (i.e., tNE-2, −3, −9, −12, −18 and −26) in testes, while the strong expressions of tNEs of Fam71d, Ms4a5 and 1700025F22Rik were assumed to be due to the testis-specific expression of the genes.

We hypothesized that the insertion of novel exons could produce new UTRs or protein variants, as listed in Table 2. More than half of the testes-enriched novel exons (n = 112, 56.8%) were identified as alternative 5′-UTRs that would likely result in the differential regulation of transcription or translation in testes. Several studies have demonstrated that testes-specific 5′-UTRs include regulatory elements, such as the upstream open reading frames (uORFs), for translational regulation [21–23]. We also found that testes-enriched novel 5′-UTRs have abundant uORFs (n = 56, 50%) with some of 197 novel exons in the testes, suggesting a testes-specific regulatory role in translation. For example, more than 5 uORFs were found to be the testis-enriched 5′-UTRs of Nt5c2, Lrrc8b, Mllt11, Mphosph9, Kdm5b, Proca1, and 5730559C18Rik in 197 testis-enriched novel exons. Additionally, the inclusion of tNE-2, 3, 20 and 21 of Eya4, Skp2, Higd1a and Pkm2 could contribute to the 5′UTRs forming G-quadruplex, which is involved in translational control [24].

Insertions of tNEs may lead to dramatic changes in protein expression. (Example 1) The C-terminal truncation (~50%) of MS4A5 is related to the insertion of tNE-17. MS4A5 is known to have four membrane-spanning domains [25], but insertion of tNE-17 results in the loss of two domains. (Example 2) Prediction by cNLS mapper [26] suggests that the novel isoform of EFR3A lacks the C-terminal 131 residue sequence containing one of the nuclear localization signals (NLSs). It is also possible that tNE-13 plays an important role in the regulation of EFR3A localization in testes [27]. (Example 3) For tNE-11 belonging to Vapa, two variants showing a 9-bp difference were identified by Cufflinks (Additional file 3: Figure S1A) and were predicted to encode 38–41 additional amino acids, GKTPPGIASTVASLSSVSSAVATPASYHLKNDPRELKE (VKQ). Interestingly, it is likely that this sequence contributes to the membrane-spanning region in a testes-specific manner by the prediction using TopPred [27] (Additional file 3: Figure S1B). The function of VAPA in neurons is known to be associated with ER and microtubules [28], and tNE-11 might confer testes-specific functions via the membrane-spanning region. Collectively, these data suggest that the testes-enriched novel exons could be involved in dramatic structural changes.

Experimental confirmation of the heart-specific novel exons

Among 26 heart-enriched novel exons, 13 novel exons (hereafter, hNE) were selected for experimental validation, on the basis of their read number (expression level), easiness of primer design, and straightforward exon structures and the enrichment of 10 hNEs in heart was experimentally confirmed by qRT-PCR and RT-PCR (Figure 3C and D). Most hNEs were strongly expressed in the heart, except for hNE-1 and −9. Multiple novel exons (i.e., hNE-2, −5 and −6) were identified in Mylk4 and predicted to produce a different 5′UTR with slightly different N-terminal regions. Similar to the tNEs, the alternative 5′-UTRs containing 1–2 uORFs were observed in the hNEs for Cluh, Mylk4, Schip1, Larp5, and Nexn, suggesting heart-specific post-transcriptional regulation.

Among the variants identified, hNE-8 of Trdn is likely to result in truncation of the C-terminal region. A total of six isoforms were identified for Trdn, and their estimated sizes were approximately 1.3, 4.3, and 5 kb in the heart, and 5, 5.5, and 7 kb in skeletal muscle [29]. In addition, hNE-8 was specifically expressed in the heart and inserted in the transcripts expressed in skeletal muscle, which could result in the C-terminus-truncated TRDN. Based on analysis of data using Cufflinks, the relative expression of the isoform containing hNE-8 was predicted to be considerably lower than the known cardiac-specific isoforms (Additional file 4), suggesting a restricted role for hNE-8 of Trdn in the heart.

Several dramatic changes were predicted in the case of Sorbs1 variants containing hNE-9. This predicted additional exon was highly enriched in proline residues such as PPPAPPPDPP, PPCLPFP, PKPYIPPSTP, and PSLPTPTSVP. Proline-rich residues was known to be important for binding the SH3 domains in signaling cascades [30, 31], therefore it suggested the insertion of hNE-9 might be involved in the regulation of signaling cascade in a heart-specific manner. At present, seven known isoforms of Sorbs1 have been identified [32–34] and hNE-9 is novel and appears highly enriched in the heart. Additionally, data suggested that hNE-10 from Csde1 likely encoded a serine-rich region consisting of 46 additional residues (MENMLTVSSDPQPTPAAPPSLSLPLSSSSTSSWTKKQKRTPTYQRS). Interestingly, Ser-32 and Thr-34 of hNE-10 were predicted to be phosphorylated by PKC according to NetPhosK [35], suggesting heart-specific signal regulation.

Alternative splicing patterns of the novel isoforms containing the novel exons

We then compared the expression levels of the novel isoforms containing the novel exons to those of the known isoforms. As seen in Figure 4, at least 10 novel isoforms exhibited dominant expression when compared with the previously known isoforms in the heart or testes. More than 90% of the expressions of Scamp2, Vapa, Zfp385a, 1700001C02Rik, Fam71d, 1700025F22Rik, and Mtmr6 were identified in the novel isoforms in testes, suggesting testes-specific roles of the isoforms. For Mtmr6, a recent study reported that the testes-specific MTMR6 protein had a slightly higher molecular weight than the known protein, but the similar portions of the novel and known isoforms were observed at a protein level [36].

Alternative splicing patterns of the novel isoforms containing the novel exons. (A) Multiple isoforms either with or without the novel exons were produced by RT-PCR. Exon structures amplified by the primers are seen in the right panel, while novel exons are highlighted with blue boxes. (B) The relative expression levels of the isoforms were quantified by ImageJ.

Conversely, the novel isoforms for Pkm2, Ms4a5, Pfkm, and Skp2 were expressed at relatively low levels in the testes. Unexpected isoforms were observed in Zfp385a, 1700001C02Rik, Fam71d, Mtmr6, and Zfand6, implying incomplete coverage in spite of the high-resolution of NGS. However, the rapidly accumulating datasets will help complete a mouse gene annotation.

Expressional changes of heart-specific novel exons during cardiac hypertrophy

For the identified hNEs, we investigated the alternative splicing patterns occurring during cardiac hypertrophy induced by transverse aortic constriction (TAC). The number of reads mapped to all exons, including hNEs, were calculated using our RNA-Seq dataset (E-MTAB-727) on cardiac hypertrophy [37], and the differential expression levels of hNEs were identified using DEXSeq [38]. Two differentially expressed hNEs (hNE-1 and −9 for Cluh and Sorbs1, respectively) were obtained (p < 0.05) (Additional file 5: Table S3) from the analysis. As seen in Figure 5A, the expression of Cluh was significantly decreased by ~36% (p = 0.015), while the expression of hNE-1 decreased by ~65% during cardiac hypertrophy (p = 0.007), indicating that hNE-1 in Cluh was alternatively spliced during cardiac hypertrophy (gene vs. hNE-1 in TAC, p = 0.046). Cufflinks analysis (Additional file 6: Figure S3) indicated that the portion of the novel isoform containing hNE-1 represented approximately 33% of the expression of Cluh in the heart, and that the predicted protein derived from the isoform was 38 residues shorter than the known isoform. The expression of the heart-specific minor isoform containing hNE-1 was thought to be down-regulated during cardiac hypertrophy.

Alternative splicing patterns of the novel exons of Cluh and Sorbs1 during cardiac hypertrophy. (A) The expression levels of Cluh and hNE-1, (B) Sorbs1 and hNE-9, measured by qRT-PCR. Black and gray bars indicate the expression levels in Sham and TAC (n = 3 for each model), respectively, and (C) expression patterns measured by RT-PCR.

The expression of hNE-9 in Sorbs1 was also significantly decreased during cardiac hypertrophy. While the expression of Sorbs1 gene was not changed (p = 0.34), the expression of hNE-9 was significantly decreased by ~36% (p = 0.037) (Figure 5B). Thus, hNE-9 was thought to be excluded during cardiac hypertrophy suggesting a disease-related function associated with hNE-9 in the heart. Therefore, we examined the relationship between cardiac hypertrophy and hNEs, and further experimentally validated the significant exclusion of hNE-1 and −9 of Cluh and Sorbs1 during TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy. As no changes were indicated in exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy (Table S3), we concluded that the exclusion of these exons could be related to pathology of the heart.

Conclusions

The results of this study will contribute to updating mouse gene annotation through the identification of specific tissue-enriched novel transcripts and novel exons. Tissue-specific isoform switches mediated by novel exons could provide important insights into the tissue-specific roles of the novel exons. The exclusion of the hNEs during cardiac hypertrophy also suggested sensitivity of the novel exons to pathological status. Our findings emphasize the necessity of this approach to identify tissue-specific novel transcripts and exons.

Methods

Ethics Statement

All animal experiments and animal ethics were approved by the GIST Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) (Permit number: GIST-2013-22).

Identification of novel transcripts and exons

‘Tophat-Cufflinks-Cuffompare’ pipeline was used to identify novel transcripts and exons. Fastq files for six mouse tissues (brain, cerebrum, kidney, heart, liver and testis) in GSE30352 were downloaded and the reads were further aligned to mouse genome (UCSC mm9 version) using ‘Tophat’. Using resultant Bam files, de novo assembly was performed to construct the transcripts using ‘Cufflinks’. All transcripts were then compared to the predefined gene annotations such as UCSC and ENSEMBL using ‘Cuffcompare’. To identify the novel transcripts, we collected the transcripts located in intergenic region and classified as “unknown” in both UCSC and ENSEMBL as putative novel transcripts. In case of novel exons, we searched the consecutive novel junctions in-between the known neighbouring exons, thereby deduced the novel exons spanning the novel junctions.

Tissue-specificity of novel transcripts and exons

Numbers of the reads for the novel transcripts and exons were counted for heart, testis, liver, kidney, cerebrum and brain using HTSeq [39]. Multiple tests for the novel transcripts and exons were performed for a specific tissue vs. remaining tissues using DESeq and DEXSeq [14, 38], respectively, in a pairwise manner. The novel transcripts and exons significantly enriched in a specific tissue compared to all other tissues (p < 0.05) were collected.

Alternative splicing of heart-enriched novel exons during cardiac hypertrophy

Differential expression of the heart-enriched novel exons during cardiac hypertrophy were analysed using ‘Tophat-HTSeq-DEXSeq’ pipeline. Fastq files of previously reported RNA-Seq datasets on TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy were aligned to mouse genome (UCSC mm9 version) using Tophat [12]. Number of the reads mapped onto the genes containing the heart-enriched novel exons were counted using HTSeq. Then, the differential expression of the heart-enriched exons during cardiac hypertrophy were analysed using DEXSeq (p < 0.05).

Transverse aortic constriction operation

Cardiac hypertrophy was induced by TAC operation under anesthesia with intraperitoneal injection of avertin, 2-2-2 tribromoethanol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in tert-amyl alcohol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The procedure of operation was followed as previously described [37]. As a control group, sham operation (same procedure except for tying) was done. 1 week after operation, mice were sacrificed, and hearts were removed, and then stored in deep freezer at -80°C before RNA extraction.

Tissue preparation and RNA isolation

Adult (8 weeks old) C57BL6 mouse heart, testes, liver, kidney, brain and lung were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, stores at -80°C, and homogenized in liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle. Approximately 450–700 mg of grinded whole mouse heart was used for extraction of total RNA with 1 ml Trizol Reagent® (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

RT-PCR and qRT-PCR

First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA with Random hexamer using Omniscript® reverse transcription (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, qRT-PCR assays were performed using TOPreal™ qPCR premix (Enzynomics, Korea) under the following two-step conditions: denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds followed by annealing and extension at 60°C for 40 seconds, for a total of 40 cycles. The 18S transcript was used as an endogenous reference to assess the relative level of mRNA transcript. RT-PCR assays were performed on a ABI thermal cycler TP600 (TaKaRa, Japan) using nTaq-HOT DNA polymerase (Enzynomics, Daejeon, South Korea) under the following 3 step conditions: denaturation at 94°C for 30s, annealing at 55-60°C for 30s and extension at 72°C for 40s with total 35–37 cycles. All primer pairs are listed in Additional file 7: Table S4.

Availability

GSE30352 and E-MTAB-727 are publicly available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) databases, respectively.

Abbreviations

- NGS:

-

Next generation sequencing

- AS:

-

Alternative splicing

- SAGE:

-

Serial analysis of gene expression

- RNA-Seq:

-

RNA Sequencing

- TNBC:

-

Triple negative breast cancer

- HER:

-

human epidermal growth factor receptor

- UCSC:

-

University of California, Santa Cruz

- FPKM:

-

Fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped

- NLS:

-

Nuclear localization signal

- TAC:

-

Transverse aortic constriction.

References

Eswaran J, Horvath A, Godbole S, Reddy SD, Mudvari P, Ohshiro K, Cyanam D, Nair S, Fuqua SA, Polyak K, Florea LD, Kumar R: RNA sequencing of cancer reveals novel splicing alterations. Sci Rep. 2013, 3: 1689-

Chen FC, Chen CJ, Ho JY, Chuang TJ: Identification and evolutionary analysis of novel exons and alternative splicing events using cross-species EST-to-genome comparisons in human, mouse and rat. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006, 7: 136-

Pan YX, Xu J, Bolan E, Moskowitz HS, Xu M, Pasternak GW: Identification of four novel exon 5 splice variants of the mouse mu-opioid receptor gene: functional consequences of C-terminal splicing. Mol Pharmacol. 2005, 68 (3): 866-875.

Kamper N, Kessler J, Temme S, Wegscheid C, Winkler J, Koch N: A novel BAT3 sequence generated by alternative RNA splicing of exon 11B displays cell type-specific expression and impacts on subcellular localization. PLoS One. 2012, 7 (4): e35972-

Chen G, Li R, Shi L, Qi J, Hu P, Luo J, Liu M, Shi T: Revealing the missing expressed genes beyond the human reference genome by RNA-Seq. BMC Genomics. 2011, 12: 590-

Forster SC, Finkel AM, Gould JA, Hertzog PJ: RNA-eXpress annotates novel transcript features in RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics. 2013, 29 (6): 810-812.

Jakhesara SJ, Koringa PG, Joshi CG: Identification of novel exons and transcripts by comprehensive RNA-Seq of horn cancer transcriptome in Bos indicus. J Biotechnol. 2013, 165 (1): 37-44.

Sun L, Zhang Z, Bailey TL, Perkins AC, Tallack MR, Xu Z, Liu H: Prediction of novel long non-coding RNAs based on RNA-Seq data of mouse Klf1 knockout study. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012, 13: 331-

Cabili MN, Trapnell C, Goff L, Koziol M, Tazon-Vega B, Regev A, Rinn JL: Integrative annotation of human large intergenic noncoding RNAs reveals global properties and specific subclasses. Genes Dev. 2011, 25 (18): 1915-1927.

Lee JH, Gao C, Peng G, Greer C, Ren S, Wang Y, Xiao X: Analysis of transcriptome complexity through RNA sequencing in normal and failing murine hearts. Circ Res. 2011, 109 (12): 1332-1341.

Brawand D, Soumillon M, Necsulea A, Julien P, Csardi G, Harrigan P, Weier M, Liechti A, Aximu-Petri A, Kircher M, Albert FW, Zeller U, Khaitovich P, Grutzner F, Bergmann S, Nielsen R, Paabo S, Kaessmann H: The evolution of gene expression levels in mammalian organs. Nature. 2011, 478 (7369): 343-348.

Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL: TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013, 14 (4): R36-

Roberts A, Pimentel H, Trapnell C, Pachter L: Identification of novel transcripts in annotated genomes using RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2011, 27 (17): 2325-2329.

Anders S, Huber W: Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010, 11 (10): R106-

Howald C, Tanzer A, Chrast J, Kokocinski F, Derrien T, Walters N, Gonzalez JM, Frankish A, Aken BL, Hourlier T, Vogel JH, White S, Searle S, Harrow J, Hubbard TJ, Guigo R, Reymond A: Combining RT-PCR-seq and RNA-seq to catalog all genic elements encoded in the human genome. Genome Res. 2012, 22 (9): 1698-1710.

Da Ros V, Busso D, Cohen DJ, Maldera J, Goldweic N, Cuasnicu PS: Molecular mechanisms involved in gamete interaction: evidence for the participation of cysteine-rich secretory proteins (CRISP) in sperm-egg fusion. Soc Reprod Fertil Suppl. 2007, 65: 353-356.

Goodrich JA, Kugel JF: Non-coding-RNA regulators of RNA polymerase II transcription. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006, 7 (8): 612-616.

Martianov I, Ramadass A, Serra Barros A, Chow N, Akoulitchev A: Repression of the human dihydrofolate reductase gene by a non-coding interfering transcript. Nature. 2007, 445 (7128): 666-670.

Beltran M, Puig I, Pena C, Garcia JM, Alvarez AB, Pena R, Bonilla F, de Herreros AG: A natural antisense transcript regulates Zeb2/Sip1 gene expression during Snail1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Genes Dev. 2008, 22 (6): 756-769.

Wang H, Iacoangeli A, Lin D, Williams K, Denman RB, Hellen CU, Tiedge H: Dendritic BC1 RNA in translational control mechanisms. J Cell Biol. 2005, 171 (5): 811-821.

Lagace M, Xuan JY, Young SS, McRoberts C, Maier J, Rajcan-Separovic E, Korneluk RG: Genomic organization of the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis and identification of a novel testis-specific transcript. Genomics. 2001, 77 (3): 181-188.

Steel LF, Telly DL, Leonard J, Rice BA, Monks B, Sawicki JA: Elements in the murine c-mos messenger RNA 5′-untranslated region repress translation of downstream coding sequences. Cell Growth Differ. 1996, 7 (10): 1415-1424.

Huang CJ, Lin WY, Chang CM, Choo KB: Transcription of the rat testis-specific Rtdpoz-T1 and -T2 retrogenes during embryo development: co-transcription and frequent exonisation of transposable element sequences. BMC Mol Biol. 2009, 10: 74-

Bugaut A, Balasubramanian S: 5′-UTR RNA G-quadruplexes: translation regulation and targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40 (11): 4727-4741.

Hulett MD, Pagler E, Hornby JR, Hogarth PM, Eyre HJ, Baker E, Crawford J, Sutherland GR, Ohms SJ, Parish CR: Isolation, tissue distribution, and chromosomal localization of a novel testis-specific human four-transmembrane gene related to CD20 and FcepsilonRI-beta. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001, 280 (1): 374-379.

Kosugi S, Hasebe M, Tomita M, Yanagawa H: Systematic identification of cell cycle-dependent yeast nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins by prediction of composite motifs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009, 106 (25): 10171-10176.

von Heijne G: Membrane protein structure prediction. Hydrophobicity analysis and the positive-inside rule. J Mol Biol. 1992, 225 (2): 487-494.

Skehel PA, Fabian-Fine R, Kandel ER: Mouse VAP33 is associated with the endoplasmic reticulum and microtubules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000, 97 (3): 1101-1106.

Hong CS, Ji JH, Kim JP, Jung DH, Kim DH: Molecular cloning and characterization of mouse cardiac triadin isoforms. Gene. 2001, 278 (1–2): 193-199.

Kay BK, Williamson MP, Sudol M: The importance of being proline: the interaction of proline-rich motifs in signaling proteins with their cognate domains. FASEB J. 2000, 14 (2): 231-241.

Yu H, Chen JK, Feng S, Dalgarno DC, Brauer AW, Schreiber SL: Structural basis for the binding of proline-rich peptides to SH3 domains. Cell. 1994, 76 (5): 933-945.

Sparks AB, Hoffman NG, McConnell SJ, Fowlkes DM, Kay BK: Cloning of ligand targets: systematic isolation of SH3 domain-containing proteins. Nat Biotechnol. 1996, 14 (6): 741-744.

Mandai K, Nakanishi H, Satoh A, Takahashi K, Satoh K, Nishioka H, Mizoguchi A, Takai Y: Ponsin/SH3P12: an l-afadin- and vinculin-binding protein localized at cell-cell and cell-matrix adherens junctions. J Cell Biol. 1999, 144 (5): 1001-1017.

Alcazar O, Ho RC, Fujii N, Goodyear LJ: cDNA cloning and functional characterization of a novel splice variant of c-Cbl-associated protein from mouse skeletal muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004, 317 (1): 285-293.

Blom N, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Gupta R, Gammeltoft S, Brunak S: Prediction of post-translational glycosylation and phosphorylation of proteins from the amino acid sequence. Proteomics. 2004, 4 (6): 1633-1649.

Mochizuki Y, Ohashi R, Kawamura T, Iwanari H, Kodama T, Naito M, Hamakubo T: Phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphatase myotubularin-related protein 6 (MTMR6) is regulated by small GTPase Rab1B in the early secretory and autophagic pathways. J Biol Chem. 2013, 288 (2): 1009-1021.

Song HK, Hong SE, Kim T, Kim DH: Deep RNA sequencing reveals novel cardiac transcriptomic signatures for physiological and pathological hypertrophy. PLoS One. 2012, 7 (4): e35552-

Anders S, Reyes A, Huber W: Detecting differential usage of exons from RNA-seq data. Genome Res. 2012, 22 (10): 2008-2017.

Gasteiger E, Gattiker A, Hoogland C, Ivanyi I, Appel RD, Bairoch A: ExPASy: the proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31 (13): 3784-3788.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2013M3A9A7046297), NRF-2012R1A1A2043217, and the 2014 GIST Systems Biology Infrastructure Establishment Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SEH performed in silico analyses and experiments using PCR (i.e., qPCR and RT-PCR) and HKS prepared the tissue samples. DHK supervised the project and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12864_2014_6277_MOESM1_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 1: Table S1: Tissue-specific novel transcripts. Detailed information on 184 novel transcripts are listed. The novel transcripts were identified by the pipeline of ‘Tophat-Cufflinks-Cuffcompare’. Multiple isoforms transcribed from the same transcribed loci are in the list. (XLSX 30 KB)

12864_2014_6277_MOESM3_ESM.png

Additional file 3: Figure S1: Structure of Vapa (A) Structures of Vapa and magnified image for the isoforms were illustrated using UCSC Genome browser (B) Predicted hydrophobicity of the novel exon of Vapa suggest the membrane spanning ability. TopPred was applied to predict hydrophobicity. (PNG 209 KB)

12864_2014_6277_MOESM5_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 5: Table S3: Expression levels of heart-specific novel exons (hNEs) during cardiac hypertrophy. Alternative splicing of hNEs during either transverse aortic constriction (TAC) or exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy was determined using DEXSeq. (XLSX 10 KB)

12864_2014_6277_MOESM6_ESM.png

Additional file 6: Figure S3: Relative expression levels of the isoforms for Cluh and Sorbs1 in heart. Relative expression levels of the isoforms were measured by FPKM of Cufflinks. Green bars indicate the expression levels of the isoforms containing novel exons. (PNG 32 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, SE., Song, H.K. & Kim, D.H. Identification of tissue-enriched novel transcripts and novel exons in mice. BMC Genomics 15, 592 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-15-592

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-15-592