Abstract

Background

In the intracellular pathogen Brucella spp., the activation of the stringent response, a global regulatory network providing rapid adaptation to growth-affecting stress conditions such as nutrient deficiency, is essential for replication in the host. A single, bi-functional enzyme Rsh catalyzes synthesis and hydrolysis of the alarmone (p)ppGpp, responsible for differential gene expression under stringent conditions.

Results

cDNA microarray analysis allowed characterization of the transcriptional profiles of the B. suis 1330 wild-type and Δrsh mutant in a minimal medium, partially mimicking the nutrient-poor intramacrophagic environment. A total of 379 genes (11.6% of the genome) were differentially expressed in a rsh-dependent manner, of which 198 were up-, and 181 were down-regulated. The pleiotropic character of the response was confirmed, as the genes encoded an important number of transcriptional regulators, cell envelope proteins, stress factors, transport systems, and energy metabolism proteins. Virulence genes such as narG and sodC, respectively encoding respiratory nitrate reductase and superoxide dismutase, were under the positive control of (p)ppGpp, as well as expression of the cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase, essential for chronic murine infection. Methionine was the only amino acid whose biosynthesis was absolutely dependent on stringent response in B. suis.

Conclusions

The study illustrated the complexity of the processes involved in adaptation to nutrient starvation, and contributed to a better understanding of the correlation between stringent response and Brucella virulence. Most interestingly, it clearly indicated (p)ppGpp-dependent cross-talk between at least three stress responses playing a central role in Brucella adaptation to the host: nutrient, oxidative, and low-oxygen stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Gram negative bacterial pathogen Brucella is the causative agent of brucellosis, a major zoonotic disease causing abortion and sterility in animals and “Malta fever” in humans. The latter is characterized by an undulant fever and septicemia which may be followed by a subacute or chronic infection [1]. The intracellular survival and replication of Brucella is considered the essential trait of virulence where the Brucella-containing phagosomes avoid bactericidal mechanisms by evading fusion with degradative lysosomes, a process which is mainly orchestrated by the type IV secretion system VirB [2, 3]. During the infection, Brucella is able to survive and to adapt to nutrient-poor conditions like those encountered inside the Brucella-containing vacuole. A major bacterial strategy to cope with such conditions is the activation of the stringent response, a global regulatory network providing rapid adaptation to a variety of growth-affecting stress conditions [4]. This rapid adaptation is mediated by the accumulation of an alarmone molecule called (p)ppGpp that binds to RNA polymerase, resulting in a large-scale down-regulation of the translation apparatus [5]. The well-studied stringent response is involved in the adaptation to amino acid starvation [6, 7], but also to carbon or nitrogen [6, 8–10], iron [11], and fatty acid starvation [12]. In Escherichia coli, the level of (p)ppGpp is regulated by the enzymes RelA that synthesizes the alarmone following activation by the presence of uncharged tRNAs, and SpoT, a bifunctional enzyme, able to synthesize and hydrolyse (p)ppGpp [6]. The majority of Gram-positive bacteria and the α-Proteobacteria, to which belongs Brucella spp., however, possess a single, RelA-SpoT homologue named Rel or Rsh. RelA-SpoT homologues share both conserved (p)ppGpp synthase and hydrolase domains and were demonstrated to be bifunctional in Gram-positive bacteria and in α-Proteobacteria at the examples of Sinorhizobium meliloti and Rhizobium etli[10, 13–15].

Several studies demonstrated essentiality of the stringent response in many infectious processes. An active stringent response is required for the expression of pneumolysin toxin in Streptococcus pneumoniae[16], invasiveness and the expression of the type IV secretion system Dot/Icm in Legionella pneumophila[17], and mycobacterial long-term survival within macrophages [18] as well as persistence in the murine model [19]. In biofilms, which are related to many chronic infections, nutrient limitation results in a stringent response-dependent antibiotic tolerance and increased antioxydant defenses [20]. In symbiotic α-Proteobacteria such as S. meliloti and R. etli, the stringent response controls bacterial physiology which is critical to the establishment of a successful symbiosis [15, 21]. In the latter, (p)ppGpp-dependent genes have also been identified during active growth in early exponential phase [15].

In Brucella, the unique rsh gene encodes a protein of 751 amino acids, and homology analysis showed that the synthase and hydrolase residues were conserved, which suggests that Rsh is bifunctional. In a previous study, we demonstrated the role of rsh in successful intracellular adaptation [22]. The rsh null mutant showed altered morphology, reduced survival in synthetic minimal medium, strong attenuation in cellular and murine models of infection, and lack of induction of virB expression [23]. A rsh mutant of Brucella abortus is also strongly attenuated in the macrophage model of infection and shows a higher sensitivity to NO- and acid pH-mediated bacterial killing, resulting in a lower general stress resistance than the wild-type strain [24]. Such a wide-range regulation necessitates a global gene expression study to elucidate the role of (p)ppGpp in controlling the regulatory processes and networks implicated in the survival and adaptation of brucellae to various environmental conditions. In this study, we determined the transcription profiles of the wild-type and of a rsh mutant of Brucella suis, a Brucella species pathogenic for humans, after stringent response induction in a synthetic minimal medium, partially mimicking conditions encountered by the pathogen within the host cell. Transcription profiling allowed the identification of the global rsh-dependent regulatory network in this pathogenic α-Proteobacterium, revealing, amongst others, stringent response control of methionine biosynthesis as well as of nitrate reductase, Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase and cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase. Moreover, the large number of differentially regulated genes was consistent with the pleiotropic effect of the response.

Results

Differential gene expression during stringent response in B. suis

Expression profiles of B. suis 1330 wild-type and the Δrsh mutant were generated using bacteria incubated for 4 h in minimal medium at pH 7.0, conditions known to induce expression of rsh-regulated genes in Brucella spp. and necessitating the presence of Rsh for growth [23]. Viability of the rsh mutant was not affected during this incubation period (not shown). Prior to transcriptional analysis, the deletion of rsh in the Δrsh mutant was controlled and confirmed by PCR using primers flanking the mutated region. The whole-genome microarray transcriptional profiling yielded a signal for rsh expression also in the Δrsh mutant, as the sequence of the spotted 70-mer oligo specific for rsh is located downstream of the deleted region. In addition, RT-qPCR showed that the transcription level of the neighboring gene pyrE was not significantly affected, thus confirming that the Δrsh mutation has no polar effect on transcription of genes located downstream.

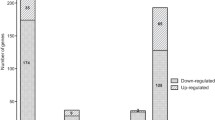

Comparative transcriptional analysis between B. suis wild-type and the Δrsh mutant revealed the Rsh-dependent differential regulation of 379 genes, which accounts for 11.6% of the genome. 198 of these genes (52%) were up-regulated and 181 genes (48%) were down-regulated by Rsh (Figure 1, and Additional file 1: Table S1).

Stringent response-regulated genes of Brucella suis 1330 have been classified into 19 functional categories. A total of 379 genes were differentially regulated in minimal medium, representing 11.6% of the Brucella genome. “Up-” (red bars) and “Down-regulated” (blue bars) refers to the wild-type situation, in the presence of functional Rsh. A: Amino acid metabolism; B: Cell Division; C: Cell envelope; D: Central intermediary metabolism; E: Chemotaxis and motility; F: Cofactor and carrier biosynthesis; G: Detoxification; H: DNA/RNA metabolism; I: Energy metabolism; J: Fatty acid metabolism; K: Nitrogen metabolism; L: Protein metabolism; M: Protein modification and repair; N: Regulation; O: Stress and adaptation/chaperones/protein folding; P: Sugar metabolism; Q: Transport systems; R: Transposon function; S: Unknown function.

The differential expression varied between a 5.3-fold Rsh-dependent up-regulation of a gene coding for a protein of unknown function (BR0629; expressed as log2: 2.41), and an 8.4-fold Rsh-dependent down-regulation (ureB-1; expressed as log2: -3.06). Differentially expressed genes were grouped into functional categories (Additional file 1: Table S1). Genes were relatively equally distributed over the different functional groups, except for a very strong representation of genes encoding proteins with unknown functions (32%). It appeared, as expected, that in B. suis, Rsh controlled a variety of different metabolic pathways through transcriptional regulation of a large number of genes. Consistent with the previously described link between the stringent response and production of (p)ppGpp, a total of 120 of the differentially expressed genes were involved in amino acid, nucleic acid, energy, fatty acid, nitrogen, protein or sugar metabolism. 31% of these metabolism genes were up-regulated and 69% were down-regulated in the presence of a functional rsh gene.

Genes up-regulated during stringent response

198 (52%) of the differentially expressed genes identified in this study were positively regulated by Rsh, characterized by a significantly higher expression rate in the wild-type than in the Δrsh strain (Additional file 1: Table S1). Among the up-regulated genes, only three (BR0793, BRA0338, BRA0340) were homologous to genes encoding enzymes involved in amino acid metabolism: BRA0338, homologous to genes encoding glutamate decarboxylase and possessing an authentic point mutation in B. suis, BRA0340, encoding a glutaminase catalyzing the formation of glutamate from glutamine, and BR0793 encoding O-acetylhomoserine sulfhydrylase, participating in the methionine biosynthesis pathway. Ten genes were implicated in DNA/RNA metabolism, including himA (BR0778) encoding the integration host factor (IHF) alpha subunit. As a transcriptional regulator, IHF binds to the promoter of the virB operon, participating in control of its expression during the intracellular and vegetative growth in various media [25]. Twelve genes, including narG and narJ from the respiratory nitrate reductase operon, and ccoN and ccoP encoding 2 cbb 3 -type cytochrome c oxidase subunits, were involved in energy metabolism. The cbb 3 -type cytochrome c oxidase is a high-oxygen-affinity terminal oxidase and hence allows brucellae to adapt to low oxygen tension. It was identified to be strongly induced under microaerobic conditions in vitro and essential for chronic, B. suis-mediated murine infection [26, 27]. Six genes involved in nitrogen metabolism and belonging to the ure2-operon were up-regulated, as well as four genes classified as belonging to protein metabolism, and one gene involved in sugar metabolism. Two genes participating in fatty acid metabolism were also up-regulated, BR1510 encoding an acyl-CoA hydrolase, and fadD (BR0289) which encodes an acyl-CoA synthase described to be required for the growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a hepatocyte cell line and in mice [28, 29] and implicated in sulfolipid production and macrophage adhesion [30]. The gene sodC, encoding a Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase participating in detoxification of free oxygen radicals [31], was also up-regulated. In addition, we observed Rsh-dependent up-regulation of two ftsK genes encoding cell division proteins. This is consistent with the morphological abnormalities described in our and another previous study on B. abortus, where a high proportion of the bacteria were characterized by a branched or unusually swollen phenotype [23, 24]. FtsK has been described to couple cell division with the segregation of the chromosome terminus [32].

The stringent response also positively affected stress-related gene expression of a number of heat and cold shock genes and molecular chaperones (grpE, hdeA, csp, dnaJ, usp). Transcription of hdeA (BRA0341) was up-regulated in the presence of rsh, and in B. abortus, HdeA contributes to acid resistance but is not required for virulence in the Balb/c murine model [33]. Several of the genes up-regulated in a Rsh-dependent manner encode functions related to transcription, with the identification of twelve transcriptional regulators belonging to different families (GntR, RpiR, MerR, LysR, Ros/MucR). GntR5 has been identified as HutC, a transcriptional regulator that exerts two different roles, as it acts as a co-activator of transcription of the virB operon, and represses the hut genes implicated in the histidine utilization pathway [34]. The regulator MucR has been described as being involved in virulence of Brucella melitensis and B. abortus in macrophage and murine models of infection [35, 36], in lipid A-core and cyclic-β-glucan synthesis in B. melitensis[37], and in the successful establishment of symbiosis in S. meliloti, including control of exopolysaccharide biosynthesis, necessary for biofilm formation [38, 39].

Several other genes encoding factors associated with Brucella virulence have been identified as being regulated by (p)ppGpp, which is in agreement with observations made in other bacterial pathogens [17, 40, 41]. These genes, up-regulated in a Rsh-dependent manner and identified in independent virulence screens [42] (the latter as review) include those involved in cell envelope formation (omp19, wbpL, lpsA, amiC, wbdA), in DNA/RNA metabolism (mutM and pyrB), in stress response (csp), in transport/secretion systems (virB5 and dppA), and one gene encoding a protein of unknown function. The roles of the cbb 3 -type cytochrome c oxidase (encoded by the genes of the operon cco) and of the Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase (encoded by sodC) were described elsewhere [26, 27]. Table 1 lists these 15 genes positively regulated by (p)ppGpp and participating in Brucella virulence.

Genes down-regulated during stringent response

In parallel, transcriptome analysis revealed 181 down-regulated genes (Additional file 1: Table S1). The gene most strongly down-regulated in the presence of Rsh was ureB1 encoding the urease beta-subunit, involved in nitrogen metabolism and forming part of the ure-1 operon. The other four genes identified as belonging to the ure-1 operon (ureC, ureD1, ureE1, and ureG1) were also repressed. The hallmark of the stringent response is the (p)ppGpp-dependent down-regulation of transcription of the genes encoding ribosomal proteins. In fact, in our transcriptome analysis, all the genes encoding ribosomal proteins identified in this transcriptome (n = 29) were down-regulated. Among the genes coding for transcriptional regulators, we identified three genes (BR1187, BR1378 and BR0872) belonging to the MerR, AspB, and ExoR family, respectively, as being down-regulated, the latter being described as repressing exopolysaccharide production. Interestingly, two genes of the flagella clusters, identified as flaF and fliG, were also affected. Flagella can be detected under certain culture conditions in Brucella, but their biological function remains yet unknown [43]. Fatty acid and glycerophospholipid biosynthesis were most likely reduced during stringent response, as we identified four genes involved in these processes being down-regulated in the presence of Rsh. Similarly, metabolism of sugars and glycolysis were apparently diminished, in agreement with a general reduction of metabolic activities. We also observed the down-regulation of the gene encoding GlnE, responsible for adenylylation of glutamine synthetase (GS). Reduced adenylylation increases GS activity, and the synthetized glutamine plays a central role in the biosynthesis of amino acids, purines, and pyrimidines.

In addition, we found a wide range of genes encoding ORFs with unknown functions to be differentially regulated during stringent response.

Validation of the microarray expression data by RT-qPCR analysis

RT-qPCR was used to validate the expression trends of selected genes identified as being differentially expressed by microarray analysis. Using the same total RNA preparations as for the microarray hybridizations, expression of selected genes, representing the previously defined different functional groups, was analyzed by RT-qPCR. Gene BR1035 of unknown function was used as internal reference for normalization, as its expression rate was constant for both strains in the experiments. The expression ratios obtained from RT-qPCR and microarrays were plotted for comparison (Figure 2, and Additional file 2: Figure S1).

Comparison of microarray analysis to real-time PCR revealed 78% of true positives. Log2-values of fold-changes of differentially expressed genes under stringent conditions are shown for normalized microarray data and RT-qPCR of 13 ORFs (out of 40 total; see also Additional file 2: Figure S1) representing the different functional groups: A- Amino acid metabolism; B- Cell Division; C- Cell envelope; D- Central intermediary metabolism; G- Detoxification. Expression of 78% of all chosen ORFs (including those presented in Additional file 2: Figure S1) was consistent for both methods, with a log2(x) > 0.66 or log2(1/x) < −0.66 (representing a plain fold-change > 1.5). For the remaining 22%, the fold-change was inferior to log2(x) = 0.66 or superior to log2(1/x) = −0.66 (representing a fold change < 1.5) or not consistent with microarray analysis. Relative differences of transcription levels between B. suis wild-type and the Δrsh mutant were determined as 2-ΔΔCt values, as described in Methods.

We investigated a total of 40 genes representing most of the previously defined functional groups. Using RT-qPCR, thirty one (78%) of the tested genes were found to be differentially expressed between wild-type and rsh-mutant, when applying a cutoff value of log2(x) > 0.66 or log2(1/x) < −0.66 (i.e. a plain fold change > 1.5), and each of these genes was regulated in the same direction (up or down), according to both RT-qPCR and the microarray study. Four other genes were identified as being regulated in the same direction (up or down) for both RT-qPCR and microarray analysis, but the rates of differential expression were not significant for RT-qPCR. Up-or down-regulation opposite to the direction of regulation obtained by the microarray study was observed by RT-qPCR for the five remaining genes, out of the total of 40. Therefore, the overall correlation between the expression levels obtained by microarrays and those obtained by RT-qPCR was good. Altogether, these results confirmed that rsh-dependent differential gene expression evidenced by oligonucleotide microarray analysis could be reproduced by RT-qPCR.

Nitrate reductase, cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase, and Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD) of B. suis are under the positive control of (p)ppGpp.

Induction of the nar operon by (p)ppGpp, as observed by microarray analysis and RT-qPCR (Additional files 1: Table S1 and 2: Figure S1), was confirmed biochemically by measurement of the enzymatic activity of the nitrate reductase operon. After a 4 h-induction of the bacteria in GMM, the NO2− production was measured in the bacterial culture supernatants. Consistent with the microarray and RT-qPCR results, significant production of NO2− was observed in the B. suis wild-type strain with a mean nitrite concentration of 698.5 ± 6.5 μM, as compared to its Δrsh isogenic mutant with a strongly reduced nitrite concentration of only 40.2 ± 6.4 μM. A ΔnarG mutant, deficient in nitrite production, was used as a negative control [44]. In the same functional group of energy metabolism, two genes encoding subunits of the cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase were also induced (Additional files 1: Table S1 and 2: Figure S1).

Both microarray and RT-qPCR results also revealed that induction of sodC, encoding Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase, was rsh-dependent (Figure 2, Additional file 1: Table S1). Production of exogenous O2 - was artificially induced by the xanthine oxydase reaction, where xanthine is converted to urate, generating O2 -. The number of surviving bacteria in the cell suspension was determined at specific time points thereafter. Despite lower initial survival of brucellae in the preculture due to pleiotropic effects of rsh mutation, there was a clear correlation between rsh expression and resistance to O2- radicals: the net difference in survival between the wild-type and the Δrsh strain was 50-fold at 30 min and 500-fold at 1 h (Figure 3). The higher sensitivity of the rsh mutant to O2- was completely abolished following complementation with the intact gene and survival was not significantly different from that of the wild-type strain (Figure 3).

The Δ rsh mutant is highly sensitive to exposure to O 2 -. Determination of the concentrations of viable B. suis wild-type (black bars), Δrsh mutant (red bars), and complemented rsh mutant (green bars) following 30 and 60 min of exposure to O2 - generated by the xanthine oxidase reaction, as described in Methods.

Growth of a rsh null mutant in minimal medium requires methionine, present in the Brucella-containing vacuole of macrophages

Lack of stringent response in a Δrsh mutant resulted in lack of growth in GMM, which was restored in the complemented strain [23]. In order to characterize the nutritional requirements of a Δrsh mutant under these growth conditions, we analyzed the amino acid requirements of the rsh null mutant in GMM. Each of the 20 culture tubes per B. suis wild-type and Δrsh strain, respectively, contained all but one of the 20 amino acids. Control cultures in medium lacking all amino acids and in medium containing all 20 amino acids (not shown), as well as a ΔmetH mutant and its complemented form, were also included. The ΔmetH mutant (BR0188) was unable to synthesize 5-methyltetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase, the last enzyme in the methionine biosynthesis pathway, transforming L-homocysteine into L-methionine. Results showed that the rsh mutant did not grow in medium lacking only methionine (Figure 4). As expected, the ΔmetH mutant behaved the same way. Growth was restored upon the addition of methionine, indicating that only the methionine biosynthesis pathway was affected in the Δrsh mutant able to synthesize all other amino acids under nutrient starvation (Figure 4). Addition of exogenous methionine to the wild-type and to the complemented ΔmetH mutant favoured earlier growth of the strains as compared to growth rates in GMM lacking methionine.

Growth of the Δ rsh mutant in minimal medium requires addition of methionine only. B. suis 1330 wild-type (black), B. suis strains Δrsh (red), ΔmetH (blue) and ΔmetH complemented with the metH gene on plasmid pBBR1-MCS (green), were grown in TS medium overnight, washed twice, and diluted 1/500 in GMM in the absence (dashed lines) or presence (solid lines) of methionine. Bacterial growth was measured at λ 600 nm. Both Δrsh and ΔmetH mutants were unable to grow in the absence of methionine and both graphs superpose as a “base line”. +met: addition of exogenous methionine; +pBBR1-MCS-metH: complementation plasmid for ΔmetH mutant.

In order to determine if the lack of capacity to synthesize methionine could also explain the inability of the Δrsh mutant to replicate in the macrophage model of infection [22], the above-described metH mutant was used in the infection experiments. Interestingly, the ΔmetH mutant was not attenuated in the J774 murine macrophage model of infection (Figure 5), leading to the conclusion that this amino acid was available in the Brucella-containing vacuoles and that the intracellular attenuation of the rsh mutant was not due to amino acid starvation.

Intracellular growth of B. suis does not require bacterial methionine synthesis. Murine J774 macrophage-like cells were infected with B. suis wild-type (black) and the ΔmetH mutant (blue). The experiments were performed three times in triplicate each. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations of one representative experiment.

Microarrays and RT-qPCR data revealed that metH was not regulated in a (p)ppGpp-dependent manner under stringent conditions, in contrast to metA (BRA0486) which was down-regulated and to the gene BR0793 which was up-regulated in the presence of Rsh (Figure 2, Additional file 1: Table S1). Mutants respectively carrying the inactivated genes metA, metZ, or BR0793 encoding O-acetylhomoserine sulfhydrylase, were characterized by reduced growth in GMM (not shown). This result was consistent with the known general methionine biosynthesis pathway composed of two parallel branches, one including metA and metZ and the other BR0793. RT-qPCR was therefore employed to systematically assess an eventual link between rsh and the expression of genes located further “upstream” on the methionine biosynthesis pathway (Figure 6).

Three genes of the methionine biosynthesis pathway were positively regulated by (p)ppGpp in B. suis . The different genes encoding the enzymes involved in the pathway from L-Aspartate to L-Methionine are represented. Gene BR0793 was identified by microarray analysis and RT-qPCR, genes BR1871 and BR1274 by RT-qPCR.

The transcripts encoding aspartate kinase (BR1871) with log2(x) of the differential expression ratio wild-type/rsh = 0.89 ± 0.15, and homoserine dehydrogenase (hom; BR1274) with log2(x) of the differential expression ratio wild-type/rsh = 0.83 ± 0.51 were found to be significantly less abundant in the rsh mutant than in the wild-type strain. These data indicated that in addition to positively regulating the transcription levels of O-acetylhomoserine sulfhydrylase (BR0793), Rsh was also involved in the positive regulation of the two genes BR1274 and BR1871 encoding proteins further upstream in the central part of the methionine biosynthesis pathway, between the L-aspartate and the L-homoserine intermediate product (Figure 6).

Discussion

The stringent response reflects the adaptation of a bacterium to nutrient stress via a complex differential gene expression pattern, affecting a large number of structural and regulatory target genes and resulting in a pleiotropic phenotype. In an earlier study, some of us showed that rsh deletion mutants were characterized by altered morphology, lack of expression of virB, and reduced survival in cellular and murine models of infection [23]. In this study, we investigated the global expression profile of the stringent response using a DNA microarray approach with the aim to characterize the (p)ppGpp-dependent regulatory network, and we also focused on methionine biosynthesis, the sole amino acid whose biosynthesis pathway was controlled by stringent response in B. suis.

A comparison of the wild-type and rsh mutant transcriptomes showed that approximately 12% of the B. suis genome were under the control of Rsh, of which 52% were up-regulated and 48% were down-regulated. The differentially transcribed genes were classified into 19 functional categories.

A key element in the establishment of Brucella infection is the ability of the bacterium to resist to acid pH and nutrient deprivation within the macrophage host cells, at least in the early phase of infection. Both signals are essential for a strong induction of the T4SS in B. suis, although RNA blot experiments with a virB5-probe reveal some virB-expression in minimal medium at pH 7 [45], corresponding to our experimental conditions in this transcriptome study. Our transcriptome study showed that virB-expression was Rsh-dependent, which is in accordance with previous work of some of us [23]. On a fine-tune level, the gene encoding the alpha-subunit of the Integration Host Factor (IHF) and hutC, which both control transcription of the virB operon via specific promoter binding sites, were also up-regulated under nutrient stress conditions. In E. coli, it has been described that expression of IHF is induced under stringent response conditions and in early-stationary phase [46, 47]. The Rsh-dependent up-regulation of IHF-expression in Brucella confirmed the regulation pathway previously suggested: Brucella senses nutrient starvation via Rsh, resulting in (p)ppGpp production, which will then increase transcription of IHF, affecting the activity of the Brucella virB promoter [48]. However, the fact that overexpression of the virB operon in a B. suis Δrsh background did not restore the parental phenotype by itself (data not shown) is an additional indication that the stringent response has a pleiotropic effect on virulence factor expression. Among transcriptional regulators participating in Brucella virulence, expression of MucR was shown to be Rsh-dependent. Studies on a mucR-mutant of B. melitensis suggest that MucR regulates genes involved in nitrogen metabolism and stress response [49], as well as in lipid A-core and cyclic-β-glucan synthesis of this pathogen [37]. In this context it is important to mention that recent work on the transcriptome analysis of stringent response in the α-proteobacterium and plant symbiont R. etli reported the observation that Rsh positively controls expression of key regulators for survival during heat and oxidative stress [15]. Remarkably, about 6% of the (p)ppGpp-regulated genes in B. suis are transcriptional regulators of, most-often, uncharacterized function.

Several consecutive genes, potentially involved in resistance to acid pH, were also induced by Rsh: genes encoding the glutamate decarboxylase A (BRA0338), the glutaminase (BRA0340), and hdeA (BRA0341). Glutamate decarboxylase, which is involved in resistance of Brucella microti to pH 2.5 [50] is not functional in B. suis. This overexpression could be the remnant of a function that has been lost during the evolution of Brucella. However, this gene potentially forms an operon with hdeA (unpublished results), which plays a role in the resistance to acid stress in B. abortus[33]. These results suggest that Rsh may prepare the bacteria to respond to a possible acid stress subsequent to nutrient deficiency.

Experimental evidence indicates that production of reactive oxygen intermediates (ROIs) represents one of the primary antimicrobial mechanisms, and ROI formation has been described during macrophage infection by Brucella[51]. Among the genes positively regulated by Rsh that contribute to the virulence of Brucella, we identified sodC encoding the Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase. A sodC mutant of B. abortus was more sensitive to killing by O2− than the wild-type, and exhibited an increased susceptibility to killing in cultured macrophages and in a murine model of infection [52]. We suggest that the lack of up-regulation of this protective gene might participate in the attenuation previously described for the Δrsh mutants of Brucella[22, 23]. In addition, it has been reported recently for biofilm-forming P. aeruginosa that an active stringent response increased not only antibiotic tolerance, but also antioxydant defenses by increasing production of active catalase and SOD against endogenous oxydant production [20]. This indicated at least a partial conservation of stringent response-dependent adaptation strategies of different bacterial pathogens to various stress conditions encountered during chronic infection or biofilm formation.

One of the hallmarks of stringent response is the down-regulation of protein synthesis, together with induction of amino acid biosynthesis pathways. Based on the transcriptome results obtained for the well-studied stringent response of E. coli[7, 53] and on earlier reports [54], a major event of the stringent response consists in the repression of the translation apparatus, including ribosomal proteins. As expected, the transcriptome data of our study clearly demonstrated that the regulation of the translation apparatus is (p)ppGpp-dependent, as we identified 29 genes coding for ribosomal proteins that were down-regulated. The microarrays used in this study lack the genes of the rRNA operons of Brucella, explaining why these genes were not also identified as being down-regulated in the wild-type strain during stringent response. Regarding induction of amino acid biosynthesis pathways, it has been described that these pathways differ, depending on the bacterial species studied. In E. coli, the stringent response positively controls the biosynthesis of the branched-chain amino acids, glutamine/glutamate, histidine, lysine, methionine and threonine [54]. In B. subtilis, proteome and transcriptome analysis has shown induction of enzymes involved in branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis during stringent response [55]. The assessment of the amino acid biosynthesis pathways positively regulated by Rsh during the stringent response in B. suis revealed that only methionine biosynthesis was controlled by (p)ppGpp. As we previously put forward the hypothesis of a nutrient-poor environment during macrophage infection, based on the observation of the attenuation of several mutants affected in amino acid and nucleotide biosynthesis pathways [22, 56], we verified the possibility that Rsh-dependent methionine synthesis might be crucial during infection. We therefore constructed a ΔmetH allelic exchange mutant of B. suis, which was auxotrophic. Intracellular growth of the ΔmetH mutant, however, was not impaired, indicating that the lack of methionine biosynthesis in the Δrsh mutant did not contribute to its attenuation and that methionine was available in the Brucella-containing vacuole. Our results are in contrast to those described by Lestrate et al.[57], who observed attenuation of a B. melitensis metH transposon mutant in vitro and in vivo, but, surprisingly, in the absence of any auxotrophic phenotype in minimal medium. In addition, genome sequencing of B. melitensis has since revealed that a gene encoding an alternative enzyme functionally replacing MetH is not present [58]. Interestingly, in the α-proteobacterium and plant symbiont R. etli, (p)ppGpp-dependent upregulation of any amino acid biosynthesis pathways during stationary phase could not be evidenced. Rather, amino acid biosynthesis was down-regulated in a (p)ppGpp-independent manner under these growth conditions [15]. It therefore appears that induction of amino acid biosynthesis during stringent response is not a key feature in α-proteobacteria.

The nar operon, which encodes the respiratory nitrate reductase in Brucella, was also induced under stringent conditions, as evidenced by the microarray analysis and by dosage of the nitrites produced by the nitrate reductase. Nar-induction was shown by the Rsh-dependent, positive control of the genes narG, narJ, and narK, involved in the first step of denitrification consisting in the reduction of nitrate to nitrite, and in nitrite extrusion towards the periplasm [59, 60]. This denitrification pathway may allow Brucella to survive under low oxygen tension, using nitrogen oxides as terminal electron acceptors [61]. Denitrification can also be used by brucellae to detoxify NO produced by activated murine macrophages during infection, and part of this denitrification island is important for virulence of B. suis in vivo[44]. Recent proteomic and gene fusion studies with B. suis evidenced the induction of the nar operon under microaerobic conditions [61]. In E. coli, expression of the narGHJI operon is induced by low oxygen tension and by the presence of nitrate [62], which is imported by NarK, also responsible for nitrite export [63]. One might speculate that our observations made in GMM broth were due to low-oxygen exposure of the strains, but this appears unlikely as pre-cultures were diluted in minimal medium under vigorous shaking for 4 hours. In M. tuberculosis, oxygen concentration-independent expression of nar has been described [64], and nitrate reductase component genes narH and narI have been identified as being under the positive control of RelMtb (Rsh) under comparable nutrient starvation culture conditions [19]. It is therefore conceivable that the Brucella nitrate reductase is expressed in a stringent response-dependent manner under aerobic conditions, and further induced under hypoxia. In analogy to the observations made for the nar-operon, genes encoding cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase were also observed being under the positive control of Rsh in B. suis, despite normal oxygenation. We hypothesize that stringent response, mediating adaptation of the pathogen to nutrient stress, therefore also represents a first step of potential adaptation to successive reduction of oxygen concentrations encountered by the pathogen in the host cells, the target organs and granulomes or abcesses.

The gene sodC, encoding Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase, was also positively regulated by the product of Rsh. The mutant was significantly more sensitive to O2- radicals then the wild-type in vitro, already at short times of treatment. It has been described previously that a sodC mutant of B. abortus exhibited much greater susceptibility to killing by O2- than the parental strain [52]. The same mutant was also much more sensitive to killing in cultured macrophages, as well as in the murine model of in vivo infection, due to its inability to detoxify the O2 - generated by the respiratory burst of the phagocytes [52]. In addition to the previous observation of some of us that virB expression is Rsh-dependent [23], we therefore have now validated by a biological survival assay a second Brucella gene product whose activity was necessary for intramacrophagic and intramurine replication and whose expression was controlled by Rsh during starvation. In B. suis, stringent response therefore also participated in protection from oxidative stress. A similar observation has been reported lately for Pseudomonas aeruginosa, where stringent response mediates increase of antioxidant defenses [20].

Interestingly, both urease operons of B. suis were regulated during stringent response in GMM: The ure-1 operon, responsible for the urease activity observed in most species [65, 66], was less expressed in the (p)ppGpp-producing wild-type strain than in the mutant, whereas ure-2 was more expressed under these conditions. In rich broth, i.e. under non-stringent conditions, urease activity, correlating with expression, has been described to be at its maximum in the absence of ammonium chloride, and enzymatic activity decreases with increasing ammonium concentrations [66]. Interestingly, a similar negative regulation of urease expression during stringent response has been described in Corynebacterium glutamicum[67]. The functions of the ure-2 cluster have been unraveled only recently: it is composed of genes encoding a urea and a nickel transport system within a single operon [68]. Our results are in agreement with those published by Rossetti et al., comparing the transcriptional profiles of B. abortus under logarithmic and stationary growth phase conditions: the ure-2 operon is induced during stationary phase, known to be triggered by stringent response [69].

The observation that flaF and fliG, belonging to flagellar loci I and loci III, respectively, were down-regulated, suggested that the flagellar apparatus of Brucella was repressed under stringent conditions. This result is in agreement with the E. coli transcription profile of the stringent response, where the expression of the flhDC flagella master regulator is rapidly down-regulated [70]. Hence, bacteria appear to shut down transcription of the flagellar cascade under starvation. This strategy makes physiological sense, as it would avoid the expending scarce energy resources for one of the bacteria’s largest macromolecular complexes. In brucellae, the biological function of the flagellar components has not been determined yet, especially in the context of host cell infection. Very recently, down-regulation of flagellar genes expression by the transcriptional regulator MucR has been described in B. melitensis[37]. Our observation that MucR is positively regulated during stringent response in B. suis, whereas genes encoding the flagellar apparatus are down-regulated under the same conditions, indicates that such a link also exists in B. suis and, more generally, that (p)ppGpp is located high up in the hierarchy of gene regulation in Brucella spp.

Altogether, the transcription analysis of the stringent response in the facultatively intracellular pathogen B. suis confirmed the pleiotropic character of the (p)ppGpp-mediated adaptation to poor nutrient conditions. Several of the genes identified as being under (p)ppGpp control have also been described previously as being essential for the virulence of the pathogen [42], establishing a link between stringent response and virulence. Among these, five genes encoded proteins involved in cell envelope biosynthesis, of which four are essential for intramacrophagic replication of Brucella[42]. In addition, four outer membrane proteins (Omps) encoded by the genes BR0119, BR0971 (both putative Omps), BRA0423 (“Omp31-2”), and BR1622 (“Omp31-1”), all under the positive control of (p)ppGpp during stringent response, have also been identified previously as being up-regulated in intramacrophagic B. suis at 48 h post infection [71]. At this rather late stage of intracellular infection, B. suis shows a high level of replication, and these four genes/proteins were described as being up-regulated in both studies, indicating the potential importance of these Omps throughout the various stages of intramacrophagic infection.

Last not least, the function of 33% of the genes encoding Rsh-dependent transcripts remains unknown. This illustrates the complexity of the processes involved in adaptation to nutrient starvation while bearing in mind that knowledge of a substantial part of the Brucella genome is still limited. In this context, it is also worthwhile to mention that in E. coli, stringent response induces the alternative, stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS [7, 53]. In brucellae and other α-proteobacterial species, however, a functional analogue of RpoS was unknown. Only very recently, an intact general stress response system (GSR), including genes encoding the regulator phyR and the alternative sigma factor rpoE1, has been described for B. abortus[72]. The transcriptome analysis of the stringent response in B. suis described here did not give any indication that stringent response might directly affect expression of these two GSR-related genes. Either stringent response controls another, yet uncharacterized alternative sigma factor in Brucella, or binding of (p)ppGpp to the RNA polymerase core affects competition between sigma factors in favor of an alternative sigma factor, which could then be RpoE1, increasing specific expression of stress-related genes.

Conclusions

Rsh, the enzyme controlling stringent response by the synthesis or hydrolysis of (p)ppGpp, affects expression of more than 10% of the genes of B. suis under nutrient starvation conditions. (p)ppGpp, as a regulator of gene expression, is thereby located high up in the hierarchy of gene regulation in Brucella spp., as we identified 17 transcriptional regulators under the control of Rsh. Expression of virB, the secretion system which plays a central role in Brucella virulence, is controlled by two transcriptional regulators which have been shown to be Rsh-dependent. Our novel data from the first stringent response transcriptome analysis of an α-proteobacterial pathogen confirm that expression of additional virulence genes is also controlled by Rsh, as 14 other genes previously identified as essential for Brucella virulence are up-regulated by Rsh under nutrient starvation. This fact emphasizes the importance of stringent response in adaptation of this pathogen to the host, and yields additional explanation for our previous observations that Rsh is essential for intramacrophagic and intramurine replication.

In contrast to the work on stringent response published for other bacteria, where the biosynthesis pathways of several amino acids, respectively, are under positive (p)ppGpp control, only methionine biosynthesis is concerned in B. suis. As this amino acid is obviously not lacking in the Brucella-containing vacuole of the macrophage, we conclude that stringent response, triggered by nutrient starvation in this compartment, is crucial for the induction of a set of virulence genes, but not for the induction of the biosynthesis pathways needed to provide the lacking amino acids.

The transcriptome analysis of the stringent response in B. suis lead to the observation that the rsh mutant had a lower general stress resistance than the wild-type strain, allowing the hypothesis that stringent response and adaptation to nutrient stress may in fact trigger cross-talk with other general stress responses in Brucella, thereby preparing the pathogen to different stress conditions possibly encountered simultaneously or soon after. In the life cycle of B. suis within the host, starvation inside the macrophage cell may be the first major stress encountered. According to the transcriptome data discussed above, such cross-talk may take place between at least three stress responses playing a central role in Brucella adaptation to host: nutrient stress, oxidative stress and low-oxygen stress.

Methods

Bacterial strains and media

The Brucella reference strains used in this study were B. suis 1330 (ATCC 23444) and B. melitensis 16 M (ATCC 23456). Ultra-competent E. coli DH5α (Invitrogen) were used for cloning and plasmid production. Brucella and E. coli strains were grown in Tryptic Soy (TS) and Luria Bertani (LB) broth (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, U.S.A.), respectively. For strains carrying resistance genes, kanamycin, ampicillin, and chloramphenicol were used at a final concentration of 50 μg/ml each. B. suis stringent response assays were performed as follows: a stationary-phase overnight culture obtained in TS was washed once in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) prior to a 1:5 dilution in Gerhardt’s Modified Minimal Medium (GMM) adjusted to pH 7.0 [73], followed by incubation at 37°C with shaking for 4 h. Concentrations of live bacteria ml-1 were determined prior and after induction by CFU counting after plating of serial dilutions onto TS agar, revealing starting concentrations of approximately 109 viable bacteria ml-1 for both strains, and almost identical concentrations at the end of the experiment. Under these conditions, both strains remained fully viable but did not start active growth.

Growth assays

For the identification of amino acids essential for Δrsh growth in GMM, B. suis cultures were grown overnight at 37°C in TS broth. Bacteria were collected by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 5 min, washed twice with 9% NaCl, diluted 1:500 and used to inoculate twenty 15-mL tubes containing 3 mL of GMM, where glutamate was replaced by ammonium sulfate, and all natural amino acids added at a concentration of 1 mM each (Sigma), except one. The method was systematically applied to each of the 20 amino acids.

Isolation and labeling of B. suisgenomic DNA

Genomic DNA was isolated from B. suis culture using Qiagen DNeasy blood and tissue kit and labeled by direct incorporation of Cy-5-dCTP fluorescent dye (Amersham) using the BioPrime DNA labeling system kit (Invitrogen) that contains random primers (octamers) and Klenow fragment. For a 50-μL reaction mixture, 2 μg of genomic DNA template in 23 μL of sterile water were heated at 95°C for 10 min, combined with 20 μl of 2.5X random primers solution, heated again at 95°C for 5 min, and chilled on ice. Remaining components were added to the following final concentrations: 0.12 mM dATP, dGTP, and dTTP; 0.06 mM dCTP; 0.02 mM Cy5-dCTP; 1 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0); 0.1 mM EDTA; and 40 units of Klenow fragment. The solution was incubated at 37°C for 2 h before the reaction was stopped by adding EDTA (pH 8.0) to a final concentration of 45 mM. The fluorescence-labeled DNA was purified using the CyScribe GFX purification kit (Amersham Biosciences) and eluted in 1 mM Tris pH 8.0 and kept in the dark at 4°C.

Isolation of total RNA from B. suis

Expression profiles of B. suis 1330 wild-type and the Δrsh mutant were generated using 9 mL of bacteria incubated in GMM containing ammonium sulfate instead of glutamate, to ensure total amino acid starvation, at pH 7.0 for 4 h, conditions that are known to induce expression of rsh-regulated genes [23]. For each strain, four independent RNA preparations from four independent cultures were used. RNA extraction was performed with the RNeasy mini kit from Qiagen according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with a modified lysis step.

Briefly, after addition of ethanol/phenol solution (9:1) to the cultures, the bacteria were recovered by centrifugation. The bacterial pellet was suspended in TE buffer-lysozyme solution (Invitrogen). After 5 min of incubation, the lysate was mixed with 10% SDS and proteinase K, and incubated for 10 min at 25°C. Buffer RLT with beta-mercaptoethanol was added to the sample followed by centrifugation. The supernatant containing the RNA was recovered and transferred to RNeasy mini spin column. RNA samples were treated with RNAse-free DNase I (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration was determined at λ 260 nm using the NanoDrop ND-1000, and quality was evaluated using a Nano-Chip on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer.

Microarray construction

The pattern of the whole-genome oligo arrays was based on the sequenced genome of B. melitensis. The 70-base nucleotides representing 3,227 ORFs plus unique sequences from B. abortus and B. suis were designed by Sigma Genosys [69]. rRNAs-genes were not represented on the microarrays. Oligonucleotides were suspended in 3× SSC (Ambion) at a final concentration of 40 μM prior to robotic arraying in quadruplicates onto ultraGAPS coated glass slides (Corning) using a spotarray 72 microarray printer (Perkin Elmer). Printed slides were steamed, UV cross-linked and stored in desiccators until use.

Probe labeling and microarray slide hybridization

The RNAs were converted to cDNA and labeled with Cy3 fluorescent dyes (Amersham Biosciences), using a two-step protocol as previously described [74, 75]. Briefly, total RNA (30 μg) was first converted to cDNAs with incorporation of a chemically reactive nucleotide analog (amino allyl-dUTP) using Superscript III reverse transcriptase and random hexamers (Invitrogen). This cDNA is then “post labeled” with the reactive forms of fluoroLink Cy3-NHS esters (Amersham), which bind to the modified nucleotides. The labeled cDNAs were then combined with 0.5 μg of labeled gDNA to a final volume of 35 μL. Samples were heated at 95°C for 5 min and then kept at 45°C until hybridization, when 35 μL of 2× formamide-based hybridization buffer (50% formamide; 10× SSC; 0.2% SDS) were added to each sample. Samples were then well-mixed and applied to custom 3.2 K Brucella oligo-arrays. Prior to hybridization, oligo-arrays were pretreated by washing in 0.2% SDS, followed by 3 washes in distilled water, and immersed in pre-hybridization buffer (5 × SSC, 0.1% SDS; 1% BSA in 100 ml of water) at 45°C for at least 45 min. Immediately before hybridization, the slides were washed 4 × in distilled water, dipped in 100% isopropanol for 10 sec and dried by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 2 min.

Four slides for each condition (i.e. B. suis 1330 wild-type and the Δrsh mutant) were hybridized at 45°C for ~ 20 h in a dark, humid chamber (Corning) and then washed for 10 min at 45°C with low stringency buffer (1× SSC, 0.2% SDS), followed by two 5-min washes in a higher stringency buffer (0.1 × SSC, 0.2% SDS and 0.1 × SSC) at room temperature with agitation. Slides were dried by centrifugation at 800 × g for 2 min and immediately scanned.

Data acquisition and microarray data analysis

Hybridized microarrays were scanned using a GenePix 4000A dual-channel (635 nm and 532 nm) confocal laser scanner (Axon Instruments). The genes represented on the arrays were adjusted for background and normalized to internal controls using image analysis software (GenePixPro 4.0; Axon Instruments Inc.). Genes with fluorescent signal values below background were disregarded in all analyses. Statistical analysis was performed by Seralogix, LLC, Austin, TX, employing their computational tools termed the BioSignature Discovery System (BioSignatureDS) to determine significant gene modulations via a Bayesian z-score sliding window threshold technique and fold change. Normalizations against genomic DNA were performed as previously described [69]. The microarray data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Accession #: GSE44688), including the ortholog gene references of B. suis attributed to the spot-IDs of the microarrays. For determination of significant differential gene expression, an absolute value for z-score cut-off of +/−1.96 was employed, which is equivalent to 95% confidence for the two-sided t-test with all genes differentially expressed having a plain fold change greater than the absolute value of 1.5. More detailed description of the computational techniques employed by BioSignatureDS was described in previous publications [76, 77].

RT-qPCR analysis

Expression of randomly selected genes from most of the different functional categories (n = 19) that we defined based on microarray analysis, and which were differentially expressed between B. suis wild-type and the rsh mutant, was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR). 800 ng from the same RNA samples used for microarray hybridization were reverse-transcribed using a 6-mer random primers mix, as described earlier [75], and quantitative RT-PCR experiments were performed using the Light Cycler 480 with SYBR green chemistry to monitor and quantify the amplification rate (Roche). Primers (Sigma Genosys) were designed using Primer 3 Software (Additional file 3: Table S2) to produce an amplicon length between 150 and 250 bp. For each gene tested, the mean calculated threshold cycles (Ct) of the wild-type and the mutant were averaged and normalized to the Ct of a gene with constant expression identified in the transcriptomic analysis. The normalized Ct was used for calculating the fold change using the ΔΔCt method [78]. Briefly, relative fold change (Δrsh mutant/wild-type) = 2-ΔΔCt, where ΔCt (Gene of interest) = Ct (Gene of interest)-Ct (Reference gene of the same sample, BR1035) and ΔΔCt (Gene of interest) = ΔCt (Δrsh mutant)-ΔCt (wild-type). BR1035, characterized by constant expression in both strains in minimal medium, was used as reference gene. For each primer pair, a negative control (water) and a RNA sample without reverse transcriptase (to determine genomic DNA contamination) were included as controls during cDNA quantification. Array data were considered valid if the fold change of each gene tested by RT-qPCR was log2(x) > 0.66 or log2(1/x) < −0.66 (representing a plain fold-change > 1.5) and consistent with microarray analysis.

Nitrate reductase assay

To assess the amount of nitrite produced, the culture supernatants were assayed for nitrite accumulation by a spectrophotometric assay based on the Griess reaction [44]. B. suis wild-type and Δrsh were washed in PBS, and incubated in GMM pH 7.0 containing 10 mM of NaNO3 for 6 h at 37°C under vigorous shaking for aeration. The nitrite concentration was measured with 100 μl of pure or diluted culture supernatants in 100 μl of Griess reagent containing 1% sulfamide in 70% acetic acid, and 0.1% N (naphthyl) ethylenediamine in 60% acetic acid. A pink color indicated nitrites in the supernatants, and OD was measured at 570 nm. Nitrite concentrations between 0 and 200 μM were used for a calibration curve.

Measurement of in vitrosensitivity to superoxide production

A previously described procedure was used to follow up superoxide dismutase activity [52]. Briefly, mid-log phase cultures of B. suis wild-type, the Δrsh mutant and the complemented mutant grown in Tryptic Soy broth were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and adjusted to a density of approximately 106 CFU/ml. Xanthine at the final concentration of 2 mM and 1 U/ml of xanthine oxidase were added to these cell suspensions along with 1,000 U/ml of bovine liver catalase to detoxify any H2O2 generated by spontaneous dismutation of the O2- produced during the xanthine oxydase reaction. At specific time points after initiating the xanthine oxidase reaction, the number of surviving bacteria in the cell suspension was determined by 10-fold serial dilutions and plating on TS agar. Plates were incubated for 3 days at 37°C. The means from 3 independent platings of each bacterial cell suspension were calculated, and the data obtained were expressed as log10 CFU/ml at each sampling time, ± standard deviations.

Construction of rsh and methionine mutants of B. suis

The rsh null mutant has been described previously [23]. The mutants in methionine biosynthesis genes (metA, metZ, metH and BR0793) contained a kanamycin resistance gene, replacing an internal portion of the target gene. For this purpose, 1239-, 1484-, 4045-, and 1451-bp fragments of metA, metZ, metH and BR0793, respectively, were amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA of B. suis with specific primers listed in Additional file 3: Table S2 (Sigma Genosys). These PCR fragments were inserted into pGEM-T Easy (Promega). The resulting plasmids were digested by BssHII, BsmI-BamHI, StuI, and BsmI-HindIII, respectively, to delete internal DNA fragments, and treated with T4-DNA-polymerase to obtain blunt-ended extremities. The deleted fragments were replaced by the kanamycin resistance gene excised from plasmid pUC4K using HincII. To generate met mutants, the resulting suicide plasmids were introduced into B. suis by electroporation. KanR/AmpS allelic exchange mutants were selected and validated by PCR. For complementation, the metH was excised from pGEM-T and subcloned into the ApaI-SacI sites of pBBR1MCS. The obtained plasmid pBBR1MCS-metH was transformed into ΔmetHBs. Complemented ΔmetH mutants were selected on the basis of their KanR-CmR phenotype.

Macrophage infection experiments with Brucellastrains

Experiments were performed as described previously [79]. Briefly, murine J774A.1 macrophage-like cells were infected with early-stationary-phase B. suis strains for 45 min at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 20 bacteria per cell. Cells were washed twice with PBS and re-incubated in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal calf serum and gentamicin at 30 μg/ml for at least 1 h to kill extracellular bacteria. After incubation of macrophages at 37°C and 5% CO2 for various time periods, cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed in 0.2% Triton X-100. The number of intracellular live bacteria was determined by plating serial dilutions on TS agar plates and incubation at 37°C for 3 days. All experiments were performed at least three times in triplicate.

References

Franco MP, Mulder M, Gilman RH, Smits HL: Human brucellosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007, 7: 775-786. 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70286-4.

Celli J, de Chastellier C, Franchini DM, Pizarro-Cerda J, Moreno E, Gorvel JP: Brucella evades macrophage killing via VirB-dependent sustained interactions with the endoplasmic reticulum. J Exp Med. 2003, 198: 545-556. 10.1084/jem.20030088.

O’Callaghan D, Cazevieille C, Allardet-Servent A, Boschiroli ML, Bourg G, Foulongne V, Frutos P, Kulakov Y, Ramuz M: A homologue of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB and Bordetella pertussis Ptl type IV secretion systems is essential for intracellular survival of Brucella suis. Mol Microbiol. 1999, 33: 1210-1220.

Cashel M, Gallant J: Two compounds implicated in the function of the RC gene of Escherichia coli. Nature. 1969, 221: 838-841. 10.1038/221838a0.

Toulokhonov I, Artsimovitch I, Landick R: Allosteric control of RNA polymerase by a site that contacts nascent RNA hairpins. Science. 2001, 292: 730-733. 10.1126/science.1057738.

Murray KD, Bremer H: Control of spoT-dependent ppGpp synthesis and degradation in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1996, 259: 41-57. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0300.

Traxler MF, Summers SM, Nguyen HT, Zacharia VM, Hightower GA, Smith JT, Conway T: The global, ppGpp-mediated stringent response to amino acid starvation in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2008, 68: 1128-1148. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06229.x.

Xiao H, Kalman M, Ikehara K, Zemel S, Glaser G, Cashel M: Residual guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate synthetic activity of relA null mutants can be eliminated by spoT null mutations. J Biol Chem. 1991, 266: 5980-5990.

Boutte CC, Crosson S: The complex logic of stringent response regulation in Caulobacter crescentus: starvation signalling in an oligotrophic environment. Mol Microbiol. 2011, 80: 695-714. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07602.x.

Krol E, Becker A: ppGpp in Sinorhizobium meliloti: biosynthesis in response to sudden nutritional downshifts and modulation of the transcriptome. Mol Microbiol. 2011, 81: 1233-1254. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07752.x.

Vinella D, Albrecht C, Cashel M, D’Ari R: Iron limitation induces SpoT-dependent accumulation of ppGpp in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2005, 56: 958-970. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04601.x.

Potrykus K, Cashel M: (p) ppGpp: Still Magical?*. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008, 62: 35-51. 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162903.

Mittenhuber G: Comparative genomics and evolution of genes encoding bacterial (p)ppGpp synthetases/hydrolases (the Rel, RelA and SpoT proteins). J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001, 3: 585-600.

Hogg T, Mechold U, Malke H, Cashel M, Hilgenfeld R: Conformational antagonism between opposing active sites in a bifunctional RelA/SpoT homolog modulates (p) ppGpp metabolism during the stringent response. Cell. 2004, 117: 57-68. 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00260-0.

Vercruysse M, Fauvart M, Jans A, Beullens S, Braeken K, Cloots L, Engelen K, Marchal K, Michiels J: Stress response regulators identified through genome-wide transcriptome analysis of the (p)ppGpp-dependent response in Rhizobium etli. Genome Biol. 2011, 12: R17-10.1186/gb-2011-12-2-r17.

Kazmierczak KM, Wayne KJ, Rechtsteiner A, Winkler ME: Roles of rel(Spn) in stringent response, global regulation and virulence of serotype 2 Streptococcus pneumoniae D39. Mol Microbiol. 2009, 72: 590-611. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06669.x.

Dalebroux ZD, Edwards RL, Swanson MS: SpoT governs Legionella pneumophila differentiation in host macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 2009, 71: 640-658. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06555.x.

Primm TP, Andersen SJ, Mizrahi V, Avarbock D, Rubin H, Barry CE: The stringent response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is required for long-term survival. J Bacteriol. 2000, 182: 4889-4898. 10.1128/JB.182.17.4889-4898.2000.

Dahl JL, Kraus CN, Boshoff HI, Doan B, Foley K, Avarbock D, Kaplan G, Mizrahi V, Rubin H, Barry CE: The role of RelMtb-mediated adaptation to stationary phase in long-term persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003, 100: 10026-10031. 10.1073/pnas.1631248100.

Nguyen D, Joshi-Datar A, Lepine F, Bauerle E, Olakanmi O, Beer K, McKay G, Siehnel R, Schafhauser J, Wang Y, et al: Active starvation responses mediate antibiotic tolerance in biofilms and nutrient-limited bacteria. Science. 2011, 334: 982-986. 10.1126/science.1211037.

Wells DH, Long SR: The Sinorhizobium meliloti stringent response affects multiple aspects of symbiosis. Mol Microbiol. 2002, 43: 1115-1127. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02826.x.

Köhler S, Foulongne V, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Bourg G, Teyssier J, Ramuz M, Liautard JP: The analysis of the intramacrophagic virulome of Brucella suis deciphers the environment encountered by the pathogen inside the macrophage host cell. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002, 99: 15711-15716. 10.1073/pnas.232454299.

Dozot M, Boigegrain RA, Delrue RM, Hallez R, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Danese I, Letesson JJ, De Bolle X, Köhler S: The stringent response mediator Rsh is required for Brucella melitensis and Brucella suis virulence, and for expression of the type IV secretion system virB. Cell Microbiol. 2006, 8: 1791-1802. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00749.x.

Kim S, Watanabe K, Suzuki H, Watarai M: Roles of Brucella abortus SpoT in morphological differentiation and intramacrophagic replication. Microbiology. 2005, 151: 1607-1617. 10.1099/mic.0.27782-0.

Sieira R, Comerci DJ, Pietrasanta LI, Ugalde RA: Integration host factor is involved in transcriptional regulation of the Brucella abortus virB operon. Mol Microbiol. 2004, 54: 808-822. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04316.x.

Loisel-Meyer S, Jiménez de Bagüés MP, Köhler S, Liautard JP, Jubier-Maurin V: Differential use of the two high-oxygen-affinity terminal oxidases of Brucella suis for in vitro and intramacrophagic multiplication. Infect Immun. 2005, 73: 7768-7771. 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7768-7771.2005.

Jiménez de Bagüés MP, Loisel-Meyer S, Liautard JP, Jubier-Maurin V: Different roles of the two high-oxygen-affinity terminal oxidases of Brucella suis: Cytochrome c oxidase, but not ubiquinol oxidase, is required for persistence in mice. Infect Immun. 2007, 75: 531-535. 10.1128/IAI.01185-06.

Rindi L, Bonanni D, Lari N, Garzelli C: Requirement of gene fadD33 for the growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a hepatocyte cell line. New Microbiol. 2004, 27: 125-131.

Dunphy KY, Senaratne RH, Masuzawa M, Kendall LV, Riley LW: Attenuation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis functionally disrupted in a fatty acyl-coenzyme A synthetase gene fadD5. J Infect Dis. 2010, 201: 1232-1239. 10.1086/651452.

Lynett J, Stokes RW: Selection of transposon mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with increased macrophage infectivity identifies fadD23 to be involved in sulfolipid production and association with macrophages. Microbiology. 2007, 153: 3133-3140. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/007864-0.

Fee JA: Regulation of sod genes in Escherichia coli: relevance to superoxide dismutase function. Mol Microbiol. 1991, 5: 2599-2610. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01968.x.

Bigot S, Sivanathan V, Possoz C, Barre FX, Cornet F: FtsK, a literate chromosome segregation machine. Mol Microbiol. 2007, 64: 1434-1441. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05755.x.

Valderas MW, Alcantara RB, Baumgartner JE, Bellaire BH, Robertson GT, Ng WL, Richardson JM, Winkler ME, Roop RM: Role of HdeA in acid resistance and virulence in Brucella abortus 2308. Vet Microbiol. 2005, 107: 307-312. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.01.018.

Sieira R, Arocena GM, Bukata L, Comerci DJ, Ugalde RA: Metabolic control of virulence genes in Brucella abortus: HutC coordinates virB expression and the histidine utilization pathway by direct binding to both promoters. J Bacteriol. 2010, 192: 217-224. 10.1128/JB.01124-09.

Wu Q, Pei J, Turse C, Ficht TA: Mariner mutagenesis of Brucella melitensis reveals genes with previously uncharacterized roles in virulence and survival. BMC Microbiol. 2006, 6: 102-10.1186/1471-2180-6-102.

Caswell CC, Elhassanny AE, Planchin EE, Roux CM, Weeks-Gorospe JN, Ficht TA, Dunman PM, Roop RM: The diverse genetic regulon of the virulence-associated transcriptional regulator MucR in Brucella abortus 2308. Infect Immun. 2013, e-pub ahead of print, Jan 14

Mirabella A, Terwagne M, Zygmunt MS, Cloeckaert A, De Bolle X, Letesson JJ: Brucella melitensis MucR, an orthologue of Sinorhizobium meliloti MucR, is involved in resistance to oxidative, detergent and saline stresses and cell envelope modifications. J Bacteriol. 2013, 195: 453-465. 10.1128/JB.01336-12.

Bahlawane C, McIntosh M, Krol E, Becker A: Sinorhizobium meliloti regulator MucR couples exopolysaccharide synthesis and motility. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2008, 21: 1498-1509. 10.1094/MPMI-21-11-1498.

Mueller K, Gonzalez JE: Complex regulation of symbiotic functions is coordinated by MucR and quorum sensing in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 2011, 193: 485-496. 10.1128/JB.01129-10.

Aberg A, Shingler V, Balsalobre C: (p)ppGpp regulates type 1 fimbriation of Escherichia coli by modulating the expression of the site-specific recombinase FimB. Mol Microbiol. 2006, 60: 1520-1533. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05191.x.

Anderson KL, Roberts C, Disz T, Vonstein V, Hwang K, Overbeek R, Olson PD, Projan SJ, Dunman PM: Characterization of the Staphylococcus aureus heat shock, cold shock, stringent, and SOS responses and their effects on log-phase mRNA turnover. J Bacteriol. 2006, 188: 6739-10.1128/JB.00609-06.

Delrue RM, Lestrate P, Tibor A, Letesson JJ, De Bolle X: Brucella pathogenesis, genes identified from random large-scale screens. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004, 231: 1-12. 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00963-7.

Fretin D, Fauconnier A, Köhler S, Halling S, Leonard S, Nijskens C, Ferooz J, Lestrate P, Delrue RM, Danese I, et al: The sheathed flagellum of Brucella melitensis is involved in persistence in a murine model of infection. Cell Microbiol. 2005, 7: 687-698. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00502.x.

Loisel-Meyer S, Jiménez de Bagüés MP, Basseres E, Dornand J, Köhler S, Liautard JP, Jubier-Maurin V: Requirement of norD for Brucella suis virulence in a murine model of in vitro and in vivo infection. Infect Immun. 2006, 74: 1973-1976. 10.1128/IAI.74.3.1973-1976.2006.

Boschiroli ML, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Foulongne V, Michaux-Charachon S, Bourg G, Allardet-Servent A, Cazevieille C, Liautard JP, Ramuz M, O’Callaghan D: The Brucella suis virB operon is induced intracellularly in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002, 99: 1544-1549. 10.1073/pnas.032514299.

Ali Azam T, Iwata A, Nishimura A, Ueda S, Ishihama A: Growth phase-dependent variation in protein composition of the Escherichia coli nucleoid. J Bacteriol. 1999, 181: 6361-6370.

Aviv M, Giladi H, Schreiber G, Oppenheim AB, Glaser G: Expression of the genes coding for the Escherichia coli integration host factor are controlled by growth phase, rpoS, ppGpp and by autoregulation. Mol Microbiol. 1994, 14: 1021-1031. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01336.x.

Rambow-Larsen AA, Petersen EM, Gourley CR, Splitter GA: Brucella regulators: self-control in a hostile environment. Trends Microbiol. 2009, 17: 371-377. 10.1016/j.tim.2009.05.006.

Arenas-Gamboa AM, Rice-Ficht AC, Kahl-McDonagh MM, Ficht TA: Protective efficacy and safety of Brucella melitensis 16MDeltamucR against intraperitoneal and aerosol challenge in BALB/c mice. Infect Immun. 2011, 79: 3653-3658. 10.1128/IAI.05330-11.

Occhialini A, Jiménez de Bagüés MP, Saadeh B, Bastianelli D, Hanna N, De Biase D, Köhler S: The glutamic acid decarboxylase system of the new species Brucella microti contributes to its acid resistance and to oral infection of mice. J Infect Dis. 2012, 206: 1424-1432. 10.1093/infdis/jis522.

Gee JM, Kovach ME, Grippe VK, Hagius S, Walker JV, Elzer PH, Roop RM: Role of catalase in the virulence of Brucella melitensis in pregnant goats. Vet Microbiol. 2004, 102: 111-115. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2004.05.009.

Gee JM, Valderas MW, Kovach ME, Grippe VK, Robertson GT, Ng WL, Richardson JM, Winkler ME, Roop RM: The Brucella abortus Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase is required for optimal resistance to oxidative killing by murine macrophages and wild-type virulence in experimentally infected mice. Infect Immun. 2005, 73: 2873-2880. 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2873-2880.2005.

Durfee T, Hansen AM, Zhi H, Blattner FR, Jin DJ: Transcription profiling of the stringent response in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2008, 190: 1084-1096. 10.1128/JB.01092-07.

Cashel M, Gentry DR, Hernandez VJ, Vinella D: The stringent response. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. Edited by: Neidhardt FC, Curtiss RIII, Ingraham JL, Lin ECC, Low KB, Magasanik B, Reznikoff WS, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger HE. 1996, Washington, D.C: ASM Press, 1458-1496. 2

Eymann C, Homuth G, Scharf C, Hecker M: Bacillus subtilis functional genomics: global characterization of the stringent response by proteome and transcriptome analysis. J Bacteriol. 2002, 184: 2500-2520. 10.1128/JB.184.9.2500-2520.2002.

Kim S, Watarai M, Suzuki H, Makino S, Kodama T, Shirahata T: Lipid raft microdomains mediate class A scavenger receptor-dependent infection of Brucella abortus. Microb Pathog. 2004, 37: 11-19. 10.1016/j.micpath.2004.04.002.

Lestrate P, Delrue RM, Danese I, Didembourg C, Taminiau B, Mertens P, De Bolle X, Tibor A, Tang CM, Letesson JJ: Identification and characterization of in vivo attenuated mutants of Brucella melitensis. Mol Microbiol. 2000, 38: 543-551. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02150.x.

DelVecchio VG, Kapatral V, Redkar RJ, Patra G, Mujer C, Los T, Ivanova N, Anderson I, Bhattacharyya A, Lykidis A, et al: The genome sequence of the facultative intracellular pathogen Brucella melitensis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002, 99: 443-448. 10.1073/pnas.221575398.

Zumft WG: Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997, 61: 533-616.

Haine V, Dozot M, Dornand J, Letesson JJ, De Bolle X: NnrA is required for full virulence and regulates several Brucella melitensis denitrification genes. J Bacteriol. 2006, 188: 1615-1619. 10.1128/JB.188.4.1615-1619.2006.

Al Dahouk S, Loisel-Meyer S, Scholz HC, Tomaso H, Kersten M, Harder A, Neubauer H, Köhler S, Jubier-Maurin V: Proteomic analysis of Brucella suis under oxygen deficiency reveals flexibility in adaptive expression of various pathways. Proteomics. 2009, 9: 3011-3021. 10.1002/pmic.200800266.

Showe MK, DeMoss JA: Localization and regulation of synthesis of nitrate reductase in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1968, 95: 1305-1313.

Clegg S, Yu F, Griffiths L, Cole JA: The roles of the polytopic membrane proteins NarK, NarU and NirC in Escherichia coli K-12: two nitrate and three nitrite transporters. Mol Microbiol. 2002, 44: 143-155. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02858.x.

Sohaskey CD, Wayne LG: Role of narK2X and narGHJI in hypoxic upregulation of nitrate reduction by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 2003, 185: 7247-7256. 10.1128/JB.185.24.7247-7256.2003.

Bandara AB, Contreras A, Contreras-Rodriguez A, Martins AM, Dobrean V, Poff-Reichow S, Rajasekaran P, Sriranganathan N, Schurig GG, Boyle SM: Brucella suis urease encoded by ure1 but not ure2 is necessary for intestinal infection of BALB/c mice. BMC Microbiol. 2007, 7: 57-10.1186/1471-2180-7-57.

Sangari FJ, Seoane A, Rodriguez MC, Aguero J, Garcia Lobo JM: Characterization of the urease operon of Brucella abortus and assessment of its role in virulence of the bacterium. Infect Immun. 2007, 75: 774-780. 10.1128/IAI.01244-06.

Brockmann-Gretza O, Kalinowski J: Global gene expression during stringent response in Corynebacterium glutamicum in presence and absence of the rel gene encoding (p)ppGpp synthase. BMC Genomics. 2006, 7: 230-10.1186/1471-2164-7-230.

Sangari FJ, Cayon AM, Seoane A, Garcia-Lobo JM: Brucella abortus ure2 region contains an acid-activated urea transporter and a nickel transport system. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10: 107-10.1186/1471-2180-10-107.

Rossetti CA, Galindo CL, Lawhon SD, Garner HR, Adams LG: Brucella melitensis global gene expression study provides novel information on growth phase-specific gene regulation with potential insights for understanding Brucella:host initial interactions. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9: 81-10.1186/1471-2180-9-81.

Lemke JJ, Durfee T, Gourse RL: DksA and ppGpp directly regulate transcription of the Escherichia coli flagellar cascade. Mol Microbiol. 2009, 74: 1368-1379. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06939.x.

Al Dahouk S, Jubier-Maurin V, Scholz HC, Tomaso H, Karges W, Neubauer H, Köhler S: Quantitative analysis of the intramacrophagic Brucella suis proteome reveals metabolic adaptation to late stage of cellular infection. Proteomics. 2008, 8: 3862-3870. 10.1002/pmic.200800026.

Kim HS, Caswell CC, Foreman R, Roop RM, Crosson S: The Brucella abortus General Stress Response System Regulates Chronic Mammalian Infection and Is Controlled by Phosphorylation and Proteolysis. J Biol Chem. 2013, 288: 13906-13916. 10.1074/jbc.M113.459305.

Lestrate P, Dricot A, Delrue RM, Lambert C, Martinelli V, De Bolle X, Letesson JJ, Tibor A: Attenuated signature-tagged mutagenesis mutants of Brucella melitensis identified during the acute phase of infection in mice. Infect Immun. 2003, 71: 7053-7060. 10.1128/IAI.71.12.7053-7060.2003.

Hegde P, Qi R, Abernathy K, Gay C, Dharap S, Gaspard R, Hughes JE, Snesrud E, Lee N, Quackenbush J: A concise guide to cDNA microarray analysis. Biotechniques. 2000, 29: 548-550. 552–544, 556 passim

Occhialini A, Cunnac S, Reymond N, Genin S, Boucher C: Genome-wide analysis of gene expression in Ralstonia solanacearum reveals that the hrpB gene acts as a regulatory switch controlling multiple virulence pathways. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2005, 18: 938-949. 10.1094/MPMI-18-0938.

Lawhon SD, Khare S, Rossetti CA, Everts RE, Galindo CL, Luciano SA, Figueiredo JF, Nunes JE, Gull T, Davidson GS, et al: Role of SPI-1 secreted effectors in acute bovine response to Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium: a systems biology analysis approach. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e26869-10.1371/journal.pone.0026869.

Khare S, Lawhon SD, Drake KL, Nunes JE, Figueiredo JF, Rossetti CA, Gull T, Everts RE, Lewin HA, Galindo CL, et al: Systems biology analysis of gene expression during in vivo Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis enteric colonization reveals role for immune tolerance. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e42127-10.1371/journal.pone.0042127.

Hanna N, Jiménez de Bagüés MP, Ouahrani-Bettache S, El Yakhlifi Z, Köhler S, Occhialini A: The virB operon is essential for lethality of Brucella microti in the Balb/c murine model of infection. J Infect Dis. 2011, 203: 1129-1135. 10.1093/infdis/jiq163.

Jiménez de Bagüés MP, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Quintana JF, Mitjana O, Hanna N, Bessoles S, Sanchez F, Scholz HC, Lafont V, Köhler S, et al: The new species Brucella microti replicates in macrophages and causes death in murine models of infection. J Infect Dis. 2010, 202: 3-10. 10.1086/653084.

Acknowledgements