Abstract

Background

Dysregulation of microRNA (miRNA) expression has been implicated in molecular genetic events leading to the progression and development of atherosclerosis. We hypothesized that miRNA expression profiles differ between baboons with low and high serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentrations in response to diet, and that a subset of these miRNAs regulate genes relevant to dyslipidemia and risk of atherosclerosis.

Results

Using Next Generation Illumina sequencing methods, we sequenced hepatic small RNA libraries from baboons differing in their LDL-C response to a high-cholesterol, high-fat (HCHF) challenge diet (low LDL-C, n = 3; high LDL-C, n = 3), resulting in 517 baboon miRNAs: 490 were identical to human miRNAs and 27 were novel. We compared miRNA expression profiles from liver biopsies collected before and after the challenge diet and observed that HCHF diet elicited expression of more miRNAs compared to baseline (chow) diet for both low and high LDL-C baboons. Eighteen miRNAs exhibited differential expression in response to HCHF diet in high LDL-C baboons compared to 10 miRNAs in low LDL-C baboons. We used TargetScan/Base tools to predict putative miRNA targets; miRNAs expressed in high LDL-C baboons had significantly more gene targets than miRNAs expressed in low LDL-C responders. Further, we identified miRNA isomers and other non-coding RNAs that were differentially expressed in response to the challenge diet in both high LDL-C and low LDL-C baboons.

Conclusions

We sequenced and annotated baboon liver miRNAs from low LDL-C and high LDL-C responders using high coverage Next Gen sequencing methods, determined expression changes in response to a HCHF diet challenge, and predicted target genes regulated by the differentially expressed miRNAs. The identified miRNAs will enrich the database for non-coding small RNAs including the extent of variation in these sequences. Further, we identified other small non-coding RNAs differentially expressed in response to diet. Our discovery of differentially expressed baboon miRNAs in response to a HCHF diet challenge that differ by LDL-C phenotype is a fundamental step in understating the role of non-coding RNAs in dyslipidemia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), a leading cause of mortality in the United States, is commonly due to the development of atherosclerosis[1]. Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting medium and large arteries, resulting from a complex interaction between genotype and environmental factors including diet, which influences dyslipidemia. Clinical and epidemiological studies indicate that atherosclerosis is positively correlated with serum LDL-C and inversely correlated with high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C)[2–5], demonstrating that increased levels of serum LDL-C is a major risk factor for atherosclerosis[6]. However, the exact mechanism by which LDL-C promotes atherosclerosis remains an active aspect for research. Early studies by Brown and Goldstein[6] demonstrated that oxidized LDL-C (ox-LDL-C) is a prerequisite for initiation of atherosclerotic lesions, leading to the development of intermediate and complex plaques[7, 8]. Subsequent studies have confirmed that ox-LDL-C is an essential atherosclerotic risk factor, triggering arterial cellular modification[9–11]. Lowering LDL-C reduces the risk for atherosclerosis in humans, and modification of diet and lifestyle, and administration of drugs is a major strategy to control CVD[12].

Apart from the physiological characteristics, understanding the genetic mechanisms underlying dyslipidemia and subsequent development of atherosclerosis is fundamental to therapeutic interventions. Many genetic factors influencing risk factors for atherosclerosis have been identified[13], including genes underlying the vulnerability of arterial intimal layer to ox-LDL-C[10, 14]. The expression of genes important for development of atherosclerosis is modulated by a variety of elements, including microRNAs (miRNAs).

miRNAs are small endogenous non-coding RNAs that are evolutionarily conserved across many species and the biogenesis of miRNAs has been described[15, 16]. miRNAs down-regulate gene expression by translational repression[15], degradation and deadenylation[17, 18]. Occasionally miRNAs can also up-regulate gene expression[19, 20]. These small non-coding RNAs have been implicated in a range of biological processes, including cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, and cholesterol metabolism[15, 21]. These processes are important for the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis. Consequently, dysregulation of miRNA function may lead to atherosclerosis. For example, miR-365 is up-regulated by ox-LDL-C, leading to reduced expression of BCL2, an antiapoptotic gene, in arterial endothelial cells[22]. miR-155 and miR-146a are associated with accumulation of ox-LDL-C in monocytes[23, 24]. It has been shown that miR-92a controls angiogenesis of atherosclerotic plaques in mice, leading to destabilization and rupture[25]. miRNAs, let-7 and miR-17-92 cluster, are known to target thrombospondin-1, an inhibitor of angiogenesis[26]. Furthermore, miR-210, -15b, -16, and -20b are implicated in down-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor[27–29], a key gene in cell migration in the atherosclerotic lesion. Studies also indicate that the up-regulation of miR-335 and −122 is associated with lipid metabolism in obese mice[30, 31] and chimpanzee[32]. This suggests that expressed miRNAs play a fundamental role in dyslipidemia, a major risk factor for atherosclerosis. Importantly miRNAs have been shown to exhibit temporal and spatial expression patterns, emphasizing the need to define cell–type–specific miRNA expression profiles, which require expression-sensitive tools to capture low-abundance small RNAs.

Although the baboon is a well-characterized model for human biomedical studies, including CVD, very little is known about baboon (Papio hamadryas) miRNAs[16]. Discovering liver miRNAs, identifying diet responsive miRNAs that differ between low and high LDL-C responders, and understanding how miRNAs regulate gene expression in the baboon will provide insights on the role of miRNAs in dyslipidemia. In this study, we have used Next-Generation sequencing methods to perform deep sequencing of small RNA libraries derived from liver biopsies collected before and after a HCHF challenge diet from six half-sib baboons (low LDL-C, n = 3; high LDL-C, n = 3), differing in their LDL-C response to dietary fat and cholesterol. The sequence reads were aligned to human genome; notably the current draft of baboon genome is an unannotated draft assembly which does not provide chromosomal coordinates or transcript identification as with the human genome sequence. However, based on physical maps, the baboon and human genomes exhibit considerable sequence conservation and synteny[33]. We identified differentially expressed miRNAs in response to the challenge diet in the two LDL-C phenotypes and used in-silico methods to identify miRNA targets.

Results

Annotation of small RNAs and identification of novel miRNA genes

Sequencing 12 baboon liver small RNA libraries yielded a total of 2,765,191 sequence reads with an average 230,433 reads per sample ranging from 95,728 to 441,911 reads. A total of 770,816 unique tags mapped perfectly to the human genome sequence, with an average of 64,235 tags per sample ranging from 38,701 to 138,915 tags. On average 7% of the tags per sample were identical to human miRNAs. Table 1 shows the number of clusters generated, number of mapped unique tags per sample, and the proportion of tags mapped to miRNA sequences and their expression levels.

The small RNA libraries exhibited a diverse size distribution of sequence reads that aligned to human genome (Figure1). Sequence reads (22nts) were the most abundant in all sequenced libraries. The proportion of expression levels of small non-coding RNAs is shown in Figure2. miRNAs were the most abundantly expressed small RNAs (mean = 62%) in libraries from low and high LDL-C baboon livers (Figure2a). Other small non-coding RNAs such as small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), small nucleolar RNAs (sno RNAs), small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), and transfer RNAs (tRNAs) comprised 27% of the total expressed tags. Repeat-associated RNAs accounted for only 3% of the tags. Unique tags that did not map (“unclassified”) to any small non-coding RNA databases or to the human genome comprised approximately 7% of the small non-coding RNAs expressed in the baboon livers. Figure2b and 2C show the distribution of expression levels of small RNAs detected in low LDL-C and high LDL-C baboons. The mean proportion of miRNAs expressed in the high LDL-C baboon livers (67%) was higher than in low LDL-C (56%) (Figure. 2b and 2C).

Frequency of small RNAs in a) combined low and high LDL-C, b) High LDL-C only and c) Low LDL-C only liver samples. The proportion of expressed baboon small RNAs identical to human: i) miRNAs are shaded light blue, ii), other non-coding RNAs (including snoRNAs, tRNAs, siRNAs, and snRNAs) are shaded red, iii) repeat-associated RNA sequences are shaded yellow, and iv) coding transcript-associated sequences are shaded green. The proportion of mapped but unclassified sequences is shaded dark blue.

We discovered 517 miRNAs in baboon livers: 490 were identical to human miRNAs, herein referred to as known miRNAs, and 27 novel baboon miRNAs (Table 2). Each novel miRNA had a corresponding near complementary sequence, referred as miRNA star (miRNA*). Table 3 shows the total numbers of known and novel miRNAs detected from low and high LDL-C baboons on chow and HCHF diets. An average of 398 known miRNAs was detected in the 12 samples ranging from 379 to 442 miRNAs per sample. A higher number of novel miRNAs was identified in high LDL-C responders compared to low LDL-C responders (low LDL-C, n = 20; high LDL-C, n = 29). Further, we identified more novel miRNAs in baboon livers from the HCHF challenge diet than chow diet in high LDL-C responders. Table 4 shows the breakdown of miRNAs expressed in each baboon phenotype in response to the two diets. In both baboon phenotypes, the majority of known miRNAs (89%) were not diet specific, while 11% of the miRNAs were expressed only in response to a specific diet. The HCHF diet elicited expression of more miRNAs in high LDL-C responders than in low LDL-C responders (Fisher’s exact test; p = 0.0001). In contrast low LDL-C responders expressed more miRNAs on chow diet (p = 0.0001) than the HCHF diet. Thus, miRNA expression is responsive to diet and potentially associated with dyslipidemia in baboons. Additional files1 and2 contain known and novel miRNAs detected from all the liver samples.

Differential expression profiling of miRNAs responsive to dietary fat

There was a statistical difference (Fisher’s exact test; p < 0.05) between the number of miRNAs differentially expressed in high LDL-C baboons in response to HCHF diet (n = 18) compared to 10 miRNAs for low LDL-C responders. Two miRNA families are shared between the two baboon phenotypes. In this study miR-29 family members were significantly down-regulated in response to HCHF diet in both low and high LDL-C baboons. Interestingly, the expression of some miRNA gene families showed polycistronic regulation, such that a subset of members of one family was either down-regulated in one phenotype or up-regulated in another. For example, a subset of miRNA let-7 family members was down-regulated in low LDL-C baboons but up-regulated in high LDL-C baboons (Additional file1). In the Additional file3: Table S1 lists the miRNAs that were differentially expressed, p-value, fold change and the complete mature miRNA sequences.

Moreover, some miRNAs were strictly diet-specific; these miRNAs, although not differentially expressed, exhibited peculiar characteristics in which they were expressed either in response to chow diet but not HCHF diet, or vice versa (Additional file3: Table S2). In addition some miRNAs were polymorphic between low and high LDL-C baboons. For example, miR-181c and 302a were expressed in low LDL-C baboon livers while 181a and 320b were detected in high LDL-C baboon livers.

We observed that a substantial portion of sequence tags perfectly mapped to other non-coding RNAs including snoRNA, siRNA, snRNAs, and tRNAs in Rfam database. These RNAs accounted for 20-33% of the total expressed tags in the two phenotypic groups (Figures 2b and 2C). Moreover, 31% (1,064/3,456) of other non-coding RNAs in high LDL-C baboons were differentially expressed between chow and HCHF diets (False Discovery Rate (FDR) ≤ 0.05) (Additional file4). These small RNAs were not differentially expressed in low LDL-C baboon livers in response to the HCHF diet.

Targets of differentially expressed miRNAs in baboon livers

miRNA target predictions indicate many-genes- to -many-miRNAs regulation modules in which one miRNA has multiple targets, and a protein coding gene has multiple miRNA sites. A significantly higher number of targets were predicted for miRNAs differentially expressed in high LDL-C livers compared to low LDL-C livers (Fisher’s exact test; p = 0.001) (Table 5). miRNAs common in both baboon phenotypes accounted for 13% (2,931/22,598) of the total human gene targets and about 80% (111/140) of the experimentally validated targets. We found that each differentially expressed miRNA family had on average 2,124 target genes ranging from 40 to 3,586. A substantial number of rhesus targets overlapped with those in human genome. Because the currently available baboon genome is an unannotated draft sequence we were not able to perform comparative analyses with baboon and rhesus and baboon and human genomes. Furthermore, the draft baboon genome sequence is not available via the TargetScan software, Identified miRNA targets included genes that have been implicated in risk factors contributing to atherosclerosis. These targets include protein coding genes involved in lipid metabolism, fatty acid biosynthesis, and immune and inflammatory systems. We estimate that 9% (1,357/14,356) of the miRNA targets comprise CVD-related genes in human and/or in mouse.

Novel miRNAs expressed in high LDL-C livers, regardless of diet, had a greater number of predicted target genes (n = 2,448) than miRNAs expressed in low LDL-C livers (n = 2,047) (Table 6). Of the 2,448 genes targeted by novel miRNAs from high LDL-C livers, 99% (2,438/2,448) are predicted to be targeted by known miRNAs expressed in high LDL-C baboon livers. Interestingly, 80% (1,631/2047) of miRNA targets in low LDL-C baboons are predicted to be regulated by miRNAs responsive to chow diet. These results suggest that liver-expressed miRNAs in high LDL-C baboons potentially target genes responsive to elevated LDL-C concentrations while in low LDL-C responders, the majority of miRNA targets are responsive to lower concentrations of LDL-C.

Discussion

Baboon and dyslipidemia

High LDL-C is the major risk factor for atherosclerosis, the leading cause of CVD. Underlying the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis are complex networks of genes regulated by a plethora of elements including miRNAs. In this study we investigated differential expression of hepatic miRNAs in baboons differing in serum LDL-C concentrations in response to HCHF diet, and predicted miRNA targets. Liver is a major organ involved in lipid metabolism and regulation of serum cholesterol including LDL-C, and hepatic inflammation is associated with early atherosclerosis[34]. To understand the liver microRNAome relevant to LDL-C phenotype and dietary fat and cholesterol, we performed high coverage Next-Generation sequencing, annotated the baboon liver small RNA transcriptome and quantified expression of small RNAs. The baboon is a well-characterized model for dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis[35, 36], and is very similar to humans both physiologically and genetically[33]. In addition to genetic background, we are able to control diet and environment in a nonhuman primate, which is not feasible in humans. For this study, animals exhibiting discordant LDL-C serum measures (low and high LDL-C responders) were challenged for 7 weeks with a HCHF diet. Liver samples were collected from six half-sibs discordant for LDL-C before and after the challenge diet. By analyzing half-sib baboons discordant for the quantitative trait (< 2 S.D. difference), we minimized genetic variation due to genetic background and increased the likelihood that we would discover miRNAs that are diet responsive and that differ by LDL-C phenotype.

Identification of baboon liver miRNAs

The distribution of non-coding RNA sequences identified in this study is in concordance with previous studies identifying miRNAs using deep sequencing methods. The length distribution of sequence reads indicates that 22-nt fragments were the most abundant (Figure2), corresponding to the average size of mature miRNAs[37]. We identified various categories of small non-coding RNAs from baboon liver samples and observed that miRNAs were the most abundant (62%), (Figure2a), in concordance with previous studies[38, 39].

Various methods were applied in the identification of baboon miRNAs. The first study to identify baboon miRNAs employed a combined approach involving genomic computation and microarray expression[16]. In our present study, we identified 490 miRNAs identical to human miRNAs. This number far exceeds the 227 liver miRNAs identified by genomic computational prediction. Moreover, the total number of expressed baboon liver miRNAs identified by sequencing increased by 21% that detected by microarray[16]. In addition we identified 27 novel baboon miRNAs with corresponding complimentary (‘star’) sequences (Table 2). The presence of star miRNAs is compelling evidence for the DICER-like processing from a miRNA hairpin and stringency measures applied in the analysis. The identified baboon miRNAs will contribute to the species-specific miRNA database. These results demonstrate the power of parallel and high-throughput Next-Generation sequencing in elucidating differential expression profiles of miRNAs in baboon livers.

Next Generation (NG) deep sequencing has become a method of choice for discovering miRNA sequences and expression. NG technology allows detection of low copy number miRNAs in the transcriptome and discovery of novel small RNAs, with excellent reproducibility[40]. Although QRT-PCR is the method of choice for validating array-based RNA expressions, it is a relative measure of expression normalized against expression of a ‘house-keeping’ gene. In contrast, expression profiling by deep sequencing is normalized against the whole transcriptome providing more robust data in a high coverage sequencing experiment than what can be attained by QRT-PCR. For example, in this study the average read counts for baboon liver small RNAs was approximately 800,000. Moreover, NG sequencing enables detection of variation in mature miRNAs and RNA editing. Thus, deep sequencing remains an extremely sensitive approach for identifying miRNA expression levels and for detecting novel and variant miRNA sequences.

Expression of small non-coding RNAs

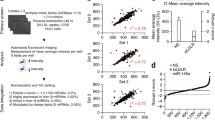

Expression profiling of non-coding RNAs in baboon livers indicated that a subset of miRNAs is diet-specific, potentially influencing LDL-C variation in baboons. A significantly higher number of miRNAs were expressed in response to HCHF challenge diet in high LDL-C baboons than in low LDL-C baboons (Table 3). In addition we have discovered miRNAs differentially expressed in response to the HCHF diet and common in both low and high LDL-C baboons (Figure3).

Several expressed miRNAs in this study were previously reported to be involved in lipid metabolism and CVD, including atherosclerosis (Table 7). For example, miR-122, which is highly abundant in liver, is associated with serum cholesterol levels in mice and primates[30, 32]. miR-221 and miR-222, which share an identical seed region, are associated with arterial smooth muscle angiogenesis[41]. Moreover, down-regulation of miR-155 and -146a is associated with enhanced accumulation of oxidized LDL-C in monocytes[23], potentiating inflammation of the intima layer of arteries and generation of atherosclerotic lesions. Further, increased expression of miR-335 is associated with elevated lipid metabolism in obese mice[31]. Our results show that miR-122 is up-regulated in response to the HCHF challenge diet in low LDL-C but down-regulated in high LDL-C baboons. miR-221 and miR-222 were significantly down-regulated in response to HCHF diet in both low and high LDL-C baboons. miR-155 and -146a were down-regulated in response to the HCHF diet in our study. Further we observed that miR-335 is up-regulated in low LDL-C baboons but is not expressed in high LDL-C animals. This may indicate that expression of some miRNAs may be dependent on the threshold level of serum cholesterol. This observation is consistent with results by Maxwell et al.[42], which indicate that reduced serum cholesterol levels may trigger expression of some genes involved in lipid metabolism. Altogether, the results from the sequence data indicate we were able to capture some of the potential miRNA candidates encoding risk factors related to atherosclerosis.

Although miR-33a/b were not differentially expressed in response to the HCHF challenge diet both miRNAs were detected in low and high LDL-C livers, however, at differing amplitudes. miR-33a was more abundant in low LDL-C while miR-33b was more abundant in high LDL-C livers. These findings are consistent with previous studies that indicate miR-33a is highly expressed in low sterol condition whereas miR-33b is more abundant in cholesterol-filled cells[50]. miR-33 family is transcribed from the introns of sterol-regulatory element-binding factor (SREBF) isoforms and is linked to cholesterol homeostasis[51].

In this study, we identified differentially expressed miRNAs that are predominantly engulfed by HDL particles[52]. miR-877 and 191 were differentially expressed in low and high LDL-C livers, respectively. The results are consistent with findings by Vickers and colleagues, indicating that miR-877 is abundantly expressed in normal individuals while miR-191 is up-regulated in familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) human subjects. Mutation in LDL receptor (LDLR) leads to FH and severe development of atherosclerotic lesions in homozygous individuals[53]. In addition we found that miR-19 was differentially expressed in high LDL-C baboons and not in low LDL-C responders. miR-19 is abundant in LDLR mutant mice[52]. Together, these findings indicate that these miRNAs are potentially involved in regulation of dyslipidemia and HDL particles may be involved in their transport to recipient cells as an anti-atherogenic mechanism.

During the biogenesis of miRNAs, a duplex RNA is generated[15]. Only a single strand (mature miRNA) is loaded into RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) while a near complementary strand, miRNA star (miRNA*), is degraded[54, 55]. Recent studies based on deep sequencing have uncovered the presence of miRNA* in different systems but in low abundance[38]. This indicates the power of deep sequencing in detecting low copy number miRNAs previously thought to be degraded. In our study we confirmed presence of miRNAs* (Additional file1). In addition we discovered that some miRNAs* exhibit higher expression than the mature miRNAs, are inversely regulated between low and high LDL-C responders, or are detected in some samples where mature miRNAs are absent. For example, miR-222* was up-regulated in response to HCHF diet in low LDL-C baboon livers but down-regulated in high LDL-C responders while mature sequences were down-regulated in both LDL-C phenotypes. These observations indicate that processing of miRNAs is regulated and that regulation of processing can affect gene expressions.

Although miRNA families have a consensus 5’ end ‘seed’ region, little is reported on upstream polymorphisms, which may affect the binding efficiency of the miRNA on mRNA UTRs, in relation to the phenotype of interest. In this study we identified some miRNAs that have nucleotide polymorphisms between low and high LDL-C responders including miR-181 and 302. miR-181 variants have identical ‘seed’ region; however, variant 181a has a G allele insertion flanking the 8-mer seed region in comparison to 181c. miR-181 has a consensus binding site in humans, chimpanzee and rhesus macaque but not mice and rats. In comparison, 302a and c have G/A substitutions at the 3’ end, contributing to differing total context scores and binding efficiency. Mice, rats, rhesus macaque, chimpanzee and humans have a consensus binding sequence for miR-302. In contrast rabbits, which are often used to model dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis do not have sites for miR-181 or 302[56].

Furthermore, differentially expressed miRNAs in baboon livers (Figure3) have been implicated to have multiple roles in different types of diseases. For example miR-16 is reportedly over-expressed in lung cancer[57], down-regulated in prostate cancer[58] and up-regulated in rheumatoid arthritis[59]. Down-regulation of miR-34b is associated with tumorogenesis suppression[60] and Parkinson’s disease[61] and its suppression via methylation confers anti-apoptotic effects on colorectal cancer[62]. miR-34b targets include TENC1 (tensin like C1 domain containing phosphatase), which has been implicated in apoptotic events in vitro[63]. These observations suggest that miRNAs have different roles in distinct tissues and that the effects on gene expression should be interpreted in the context of cell state.

Our results indicate that a significant proportion of expressed small non-coding RNAs include other miRNA-sized small non-coding RNAs such as snoRNAs, siRNAs, snRNAs and tRNAs. Non-coding RNAs (n = 3,455) were expressed in high LDL-C responders while 4,645 were identified in low LDL-C livers. We observed that 31% (1,064/3,455) of other non-coding RNAs in high LDL-C baboons were differentially expressed (FDR ≤ 0.05) in response to HCHF diet. Non-coding RNAs were not differentially expressed in low LDL-C baboons. A total of 2,277 RNAs were expressed in both baboon phenotypes including 99% of those differentially expressed in high LDL-C livers. The functional role of these small RNAs in dyslipidemia is not clear. However, prior reports indicate that deep sequencing generates a considerable number of sequence tags perfectly mapping to other known small non-coding RNAs[64]. At least one study[65] identified snoRNAs with miRNA-like function and DICER processing signatures. It is plausible these RNAs may have functional roles in dyslipidemia.

miRNAs are often expressed in gene clusters, and their transcription is thought to be closely linked[16, 66]. In this study we observed that miRNA clusters and cluster members were coordinately regulated. For example, the majority of let-7 family members are down-regulated in low LDL-C responders but up-regulated in high LDL-C responders. However, not all members of the family exhibited a coordinated pattern, suggesting an independent regulation event. A recent study[38] confirmed that some miRNAs show differential expression in distinct cells due to post-transcriptional regulation associated with variation in the levels of DICER, an enzyme involved in biosynthesis of mature miRNA. It is plausible that the expressions of some let-7 cluster members are dependent on cell context or independent of cluster transcription unit. Recent studies have uncovered the association of clustered miRNAs and complex diseases including B-cell leukemia[67, 68] and testicular carcinoma[69–71]. These miRNA clusters tend to occur in fragile regions of genomes and may be species-specific[16, 72, 73].

miRNA gene targets and atherosclerosis

Many of the predicted targets of expressed miRNA family members, with identical seed regions, overlapped considerably. Thus, it is logical to focus on identical seed regions or the miRNA family names when considering targets of miRNAs; miRNAs with same seed region are classified as one family. In this study, we sought to identify genes targeted by expressed miRNA families in low and high LDL-C baboons using in silico methods.

For differentially expressed miRNAs responsive to the HCHF diet, we observed a substantial (> 90%) overlap between targets identified in human and rhesus macaque genomes (Table 5). Because the genome assembly of baboon is in draft form, we used the rhesus genome to identify predicted gene targets. Baboon is closely related to rhesus macaque with 98% sequence identity[74]. This conservation of a large percentage of miRNA target sites between human and rhesus and the high sequence identity between rhesus and baboon suggests that our findings in baboons may translate to humans given that our data constitute sequences that are identical between human and baboon genomes. Nonetheless, a recent study[75] has shown that evolutionary changes in miRNA binding sites, may inhibit or enhance the effect of miRNAs on gene expression regulation. The study by Richardson et al. revealed that the PLIN4 3’ UTR has undergone nucleotide substitution allowing the binding of miR-522 for human individuals with A but not G allele. The miR-522 binding site with A allele was not found in Neanderthal and non-human primates suggesting a recent evolutionally change. Until an annotated baboon genome sequence is available we will not be able to assess conservation of miRNA targets sites between baboon and human and baboon and rhesus.

In this study, we observed many-genes-to-many-miRNAs regulation modules, suggesting that many genes are coordinately and cooperatively regulated by miRNAs. Genes targeted by multiple miRNAs are tightly regulated and may show graded expression in response to expression of different miRNAs. In addition, genes tightly regulated by redundant miRNAs may be an indication of their central role in the cell. We observed that, on average, about 2,000 genes are targeted by a single miRNA family, which presents daunting challenges for the development of a pharmaceutical agent with specific target. Moreover miRNA target prediction revealed that some genes are cooperatively targeted by miRNAs differing in their response to HCHF diet; i.e., one miRNA was up-regulated while the other was down-regulated in response to the HCHF diet, but both miRNAs have the same target. For example, LDLRAP1 (low density lipoprotein receptor adapter protein 1, which interacts with LDL-C receptor) is targeted by miR-27a and -26a that are up- and down-regulated, respectively, in response to the HCHF diet. The molecular interactions of these miRNAs with LDLRAP1 are not known, but it is plausible this phenomenon may be an inherent mechanism to balance gene expression levels. miR-27a and 26a are differentially regulated and implicated in adipogenesis[76, 77].

We estimate that differentially expressed miRNAs in our study targeted 9% of the total genes implicated in atherosclerosis[78, 79]. The following miRNA targets are included among those potentially associated with atherosclerosis: 1) LDLR, a cell surface protein involved in receptor-mediated endocytosis of LDL-C. Mutations in this gene cause the autosomal dominant disorder familial hypercholesterolemia[80] and increased carotid artery intima-media thickness[81]. 2) VLDLR (very low density lipoprotein receptor) plays important roles in VLDL triglyceride metabolism[82]. 3) LIPA (lipase A precursor) catalyzes the hydrolysis of cholesterol esters and triglycerides in lysosomes, and mutations in the gene is associated with impaired endothelial function in CVD[83]. Other targets of interests include PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog), which functions as a tumor suppressor by negatively regulating intracellular levels of phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate, substrates for AKT (tyrosine kinase B protein) in the intracellular AKT/PKB signaling pathway, and TENC1 (tensin-like C1 domain containing phosphatase), which is thought to act in a similar manner as PTEN in depriving substrates for AKT[84]. Further, we observed that ACVR1B (activin A receptor, type IB isoform c precursor) is considerably targeted by both novel and known miRNAs. ACVR1B is well-conserved in primates including human, rhesus, and orangutan, but relatively less-conserved in chimpanzee. ACVR1B is a receptor for activin growth factor, which belongs to TGF-beta (transforming growth factor-beta) superfamily. TGF-beta is involved and implicated in inflammatory processes, such as atherosclerosis in arteries[85]. Altogether this study identifies potential atherogenic candidate genes, targeted by differentially expressed baboon miRNAs. Identifying the roles of miRNAs and their target genes and signaling pathways in atherosclerosis will be critical for future research. miRNAs represent new regulatory factors for cardiovascular biology and are an emerging novel class of therapeutic targets for CVD.

Although identification of miRNA gene targets is a key step in elucidating miRNA functional mechanisms, comprehensive identification of targets still presents a daunting challenge. There are many bioinformatics tools available to predict miRNA targets; however, consistency among different platforms is limited[86]. In this study, we employed TargetScan, which is the most widely used tool in target prediction[87]. Because of the limitation of the high-throughput in-silico prediction, experimental validations of the miRNA-mRNA interaction are necessary. The experiments include reporter gene assay and loss- or gain-of-function of miRNA to measure target repression. However, these validation experiments are cumbersome, and, as a result, there are only a few validated miRNA targets. For example, our results generated using IPA indicate only 1% of the total miRNA targets have been validated. Recently, a high-throughput and sensitive technique for identification and quantification of miRNA targets has been reported[88]. The technique involves in-situ co-immunoprecipitation of mRNA associated with RISC, loaded with a specific miRNA, and subsequent deep sequencing. The technique, RISC-Seq, is a modification of a previous approach that utilized microarray profiling[89] and has been further optimized[90]. There is no doubt the technique provides important insight into determining the full spectrum of miRNA-mRNA interactions. However, the method is not yet fully optimized, and the modifications suggested by Matkovich et al.[90] present challenges due to over-expression of Argonaute2 protein in RISC complex, which may induce out-of-context cell state. Second, the technique does not address all outcomes of functions of miRNAs; a substantial number of miRNAs act by silencing the translation machinery and epigenetic modifications. Thus, until the RISC-Seq approach is fully optimized, in-silico prediction and basic experimental validations will remain useful approaches in deciphering the miRNA-mRNA interactions.

Conclusion

We have sequenced baboon liver small RNA samples from half-sibs discordant for serum LDL-C and were fed chow and HCHF diets. We identified 517 baboon miRNAs including 490 that are identical to human and 27 novel miRNAs. The list of miRNAs reported in this study will contribute to the public database for small RNAs. Further, we identified 30 differentially expressed miRNAs in response to a HCHF challenge diet in two distinct baboon phenotypes previously characterized for extreme responses to dietary fat. Six of these differentially expressed miRNAs have been previously identified as regulators of genes that play roles in CVD. We also identified miRNA variants and other non-coding RNAs differentially expressed in response to the HCHF diet. Analysis of target genes of the differentially expressed miRNAs showed that 9% of the currently annotated CVD-related genes are predicted to be regulated by these miRNAs. Future studies that include gene sequencing in these samples to identify all expressed genes and gene variants in combination with gene/miRNA interactions in these LDL-C responders will take us closer to understanding the genetic and epigenetic networks that underlie LDL-C response to dietary fat and cholesterol, thus providing potential central genetic targets for miRNA-based therapeutic agents to regulate LDL-C.

Methods

Animals

Baboons (Papio hamadryas) were maintained by the Southwest National Primate Research Center (SNPRC) at the Texas Biomedical Research Institute (Texas Biomed), which is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. Experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted under the supervision of Southwest National Primate Research Center staff veterinarians.

Selection of baboon sib-pairs discordant for LDL-C

Based on phenotypic and genotypic analysis of 951 pedigreed baboons, we identified three half-sib-pairs with contrasting phenotypes for LDL-C as described[91]. The sib-pairs differed by at least two standard deviations for LDL-C serum concentrations. In addition, members of each selected sibling pair were discordant for at least 1 marker loci within the support interval for an LDL-C QTL on baboon chromosome 4[92].

High-cholesterol, high-fat (HCHF) dietary challenge

The dietary challenge protocol has been described elsewhere[93, 94]. Briefly, liver biopsies were collected from the half-sib animals at baseline while consuming a basal diet (chow) low in fat (4% of calories) and cholesterol (0.03 mg/kcal). The animals were then fed the HCHF diet, high in fat (40% of calories) and cholesterol (1.7 mg/kcal), for 7 weeks, and liver biopsies were collected. Tissue samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Table 8 shows the mean and standard deviation of the LDL-C levels in low and high LDL-C baboons on chow and HCHF diets.

Liver biopsy collection

Baboons were sedated with ketamine (10 mg/kg), given atropine (0.025 mg/kg) and intubated. Anesthesia was induced and maintained with isoflurane (1-2%). Blood pressure was measured by automated arm cuff (Collin) and oxygen saturation, heart rate, and respiration were monitored by pulse oximetry. Biopsies were collected from the left lobe of the liver using Temno Evolution Needle, gauge 14 (CareFusion, San Diego, CA). During post biopsy recovery analgesia was provided in the form of Stadol, 0.15 mg/kg, bid, for 3 days and ampicillin, 25 mg/day for 10 days.

Small RNA library preparation

miRNA-enriched fractions were isolated from 10 mg of baboon liver (n = 12) using the mirVanaTM miRNA Isolation Kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and stored at −80°C until further use. Small RNA libraries were prepared from the enriched fractions with Illumina Small RNA Prep Kit v1.5 following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the Illumina 3’ adapter (5’-ATCTCGTATGCCGTCTTCTGCTTGT) was ligated to 2 μg of enriched small RNAs using T4 RNA truncated ligase (New England BioLabs) and 15% PEG at 22°C for 2 hrs. Then, the Illumina 5’ adapter (5’-GTTCAGAGTTCTACAGTCCGACGATC) was ligated onto the 3’ adapter-linked RNA using T4 RNA ligase (New England BioLabs) for 1 hr at 20°C. The 5’ and 3’ adapter-linked RNA was converted to a single-stranded cDNA using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and Illumina’s RT-Primer (5’-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The cDNA was PCR-amplified with Hotstart Phusion DNA Polymerase using the following profile: denaturation at 98°C for 30s, 15 cycles of 98°C for 10s, 60°C for 30s, 72°C for 15 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min.

The PCR product was purified on a 6% TBE urea polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen). The gel was stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV light. The gel band corresponding to 93–100 bp was excised, passed through a bottom-perforated 0.5 ml tube and eluted in 1X Elution Buffer following the manufacturer’s protocol. Notably, while the average length of a miRNA is 22 nucleotides (nts), the excised band corresponds to the total length of the adapter-ligated miRNAs. The resulting gel slurry was spun in a Spin-X filter and RNA precipitated with 2ul of glycogen, 10ul of 3 M-ammonium acetate and 325 μl of 100% cold ethanol. The mixture was centrifuged, and the resulting pellet washed with 70% ethanol. The dried RNA pellet was suspended in 10 μl of Resuspension Buffer (Illumina).

Next generation sequencing of small RNAs

Small RNA sequencing was performed using Illumina’s Genome Analyzer (GAIIx). Diluted cDNA (10 nmol/L) was amplified, sequenced, and single-read clusters generated using cBot Cluster Generation Kit and TruSeq SBS Kit v5 (36 cycles). For the control sample, we used PhiX Control Kit v3 (Illumina).

Analysis of sequence reads

Reads filtering and adapter trimming

miRNA sequence reads were analyzed using mirTools[95], an interactive web-based tool for analyzing deep sequencing reads. Briefly, the small RNA sequence reads were filtered to exclude low-quality reads and 3’/5’ adapter- and polyA-sequences. The reads were trimmed off the 3’ adapter sequences using a custom perl script. The resulting clean full-length reads were formatted into a non-redundant FASTA file. Each sequence tag in the file contains the number of reads represented by the tag.

Small RNA annotation

The resulting sequence tags (18–30 nts) were mapped onto the human genome sequence (hg18) using the SOAP2 program[96] embedded in mirTools. Subsequently, the reads were aligned against various databases including miRBase[97], Rfam[98], RepeatMasker[99], and the reference genome transcriptome database. Consequently the sequence tags were classified as a known miRNA, a degraded fragment from non-coding RNA, or RNA derived from repeat or coding sequences. Sequences that did not conform to any of the categories but mapped to a unique location on the human genome were termed “unclassified.”

Discovery of novel miRNAs

The prediction of novel miRNAs was performed by miRDeep software[54] and associated RNAfold software[100], incorporated in mirTools using default settings. Unclassified tags were used to predict candidate novel miRNAs. Using RNAfold software, a sequence fragment containing 100 nts flanking each side of the locus aligning to an unclassified tag was excised from the genome sequence. RNAfold software folds and performs computational assessment of the fragment to ensure that there is a minimum of 14 base pairings between the mature and star sequences of the hairpin. Because false positive hairpins can be formed from different types of small RNAs in the genome, miRDeep software performs further stringent analysis to test whether reads aligning to a potential miRNA precursor (pre-miRNA) are consistent with the Dicer processing signature to simulate miRNA biogenesis in the cell; presence of 2-nt 3’ overhangs and positional alignment of the reads on mature, star, or loop of the precursor sequence. Extracted sequences that do not have a Dicer signature and fold into a hairpin were discarded. An unclassified sequence tag is considered novel miRNA if it aligns to a candidate pre-miRNA. Sequences with dominantly abundant reads were denoted as mature miRNA and its complementary sequence as miRNA*.

Detection of differential expression of small RNAs

miRNAs and other non-coding RNAs differentially expressed between chow and HCHF samples were determined by assessing the read counts as described[95]. A sequence tag consists of one or more reads, which reflects the number of times the tag was sequenced, hence the expression level. We normalized an expression level of a sequence tag, within and between samples, by dividing the absolute read count by the total read count of the sample and multiplied by 1,000,000. The normalized count corresponds to the relative expression level of each tag. Normalized expression data generated from animals on chow and challenge diets were used to determine differential expression levels in each phenotype. A two-tailed student t-test was performed to test for significant expression levels for miRNAs expressed on both diets and Welch’s t-test, assuming unequal variance, was performed for miRNAs with expression detected in only one of the two groups. A small non-coding RNA was considered differentially expressed between samples when the p-value was ≤ 0.05, and multiple testing adjustments applied, where appropriate, using False Discovery Rate[101].

Target prediction

We identified potential targets of diet responsive differentially expressed miRNAs in low LDL-C and high LDL-C responders using TargetScan/Base Release 5.1 (http://www.targetscan.org/) and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (http://www.ingenuity.com) tools. We identified novel miRNA targets using TargetScan[102], employing the 7-mer seed-region of each miRNA sequence to customize prediction of targets.

Abbreviations

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- ox-LDL-C:

-

Oxidized LDL-C

- BCL2:

-

B-cell lymphoma protein 2 beta isoform

- microRNAs:

-

miRNAs

- PEG:

-

Polyethylene glycol

- HCHF:

-

High-cholesterol, high-fat

- SOAP:

-

Short oligonucleotide alignment program

- nts:

-

Nucleotides

- siRNAs:

-

Small interfering RNAs

- sno RNAs:

-

Small nucleolar RNAs

- snRNAs:

-

Small nuclear RNAs

- tRNAs:

-

Transfer RNAs

- RSC:

-

RNA-induced silencing complex

- miRNA*:

-

miRNA star

- TENC1 :

-

Tensin like C1 domain containing phosphatase

- VLDLR :

-

Very low density lipoprotein receptor

- LDLR :

-

Low density lipoprotein receptor

- LIPA :

-

Lipase A precursor

- PTEN :

-

Phosphatase and tensin homolog

- AKT :

-

Tyrosine kinase B protein

- TENC1 :

-

Tensin-like C1 domain containing phosphatase

- ACVR1B :

-

Activin A receptor, type IB isoform c precursor

- TGF-beta :

-

Transforming growth factor-beta

- cDNA:

-

Complementary DNA

- FDR:

-

False Discovery Rate.

References

Ross R: The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993, 362 (6423): 801-809.

McGill HC, McMahan CA, Kruski AW, Mott GE: Relationship of lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations to experimental atherosclerosis in baboons. Arteriosclerosis. 1981, 1 (1): 3-12.

Amarenco P, Goldstein LB, Szarek M, Sillesen H, Rudolph AE, Callahan A, Hennerici M, Simunovic L, Zivin JA, Welch KM, SPARCL Investigators: Effects of intense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol reduction in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: the Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) trial. Stroke. 2007, 38 (12): 3198-3204.

Amarenco P, Labreuche J, Touboul PJ: High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and risk of stroke and carotid atherosclerosis: a systematic review. Atherosclerosis. 2008, 196 (2): 489-496.

Assmann G, Schulte H: Relation of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides to incidence of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (the PROCAM experience). Prospective Cardiovascular Munster study. Am J Cardiol. 1992, 70 (7): 733-737.

Brown MS, Goldstein JL: Lipoprotein metabolism in the macrophage: implications for cholesterol deposition in atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1983, 52: 223-261.

McGill HC, McMahan CA, Herderick EE, Tracy RE, Malcom GT, Zieske AW, Strong JP: Effects of coronary heart disease risk factors on atherosclerosis of selected regions of the aorta and right coronary artery. PDAY Research Group. Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000, 20 (3): 836-845.

Witztum JL, Steinberg D: Role of oxidized low density lipoprotein in atherogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1991, 88 (6): 1785-1792.

Jialal I, Devaraj S: The role of oxidized low density lipoprotein in atherogenesis. J Nutr. 1996, 126 (4 Suppl): 1053S-1057S.

Daugherty A, Dunn JL, Rateri DL, Heinecke JW: Myeloperoxidase, a catalyst for lipoprotein oxidation, is expressed in human atherosclerotic lesions. J Clin Invest. 1994, 94 (1): 437-444.

Schiopu A, Frendeus B, Jansson B, Soderberg I, Ljungcrantz I, Araya Z, Shah PK, Carlsson R, Nilsson J, Fredrikson GN: Recombinant antibodies to an oxidized low-density lipoprotein epitope induce rapid regression of atherosclerosis in apobec-1(−/−)/low-density lipoprotein receptor(−/−) mice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007, 50 (24): 2313-2318.

Kushwaha RS, McGill HC: Diet, plasma lipoproteins and experimental atherosclerosis in baboons (Papio sp.). Hum Reprod Update. 1998, 4 (4): 420-429.

Monraats PS, Fang Y, Pons D, Pires NM, Pols HA, Zwinderman AH, de Maat MP, Doevendans PA, DeWinter RJ, Tio RA, Waltenberger J, Frants RR, Quax PH, van der Laarse A, van der Wall EE, Uitterlinden AG, Jukema JW: Vitamin D receptor: a new risk marker for clinical restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010, 14 (3): 243-251.

Zeibig S, Li Z, Wagner S, Holthoff HP, Ungerer M, Bultmann A, Uhland K, Vogelmann J, Simmet T, Gawaz M, Munch G: Effect of the oxLDL binding protein Fc-CD68 on plaque extension and vulnerability in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2011, 108 (6): 695-703.

Ambros V: The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004, 431 (7006): 350-355.

Karere GM, Glenn JP, VandeBerg JL, Cox LA: Identification of baboon microRNAs expressed in liver and lymphocytes. J Biomed Sci. 2010, 17: 54-

Galasso M, Elena Sana M, Volinia S: Non-coding RNAs: a key to future personalized molecular therapy?. Genome Med. 2010, 2 (2): 12-

Wu L, Fan J, Belasco JG: MicroRNAs direct rapid deadenylation of mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006, 103 (11): 4034-4039.

Orom UA, Nielsen FC, Lund AH: MicroRNA-10a binds the 5'UTR of ribosomal protein mRNAs and enhances their translation. Mol Cell. 2008, 30 (4): 460-471.

Ritchie W, Rajasekhar M, Flamant S, Rasko JE: Conserved expression patterns predict microRNA targets. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009, 5 (9): e1000513-

Guo S, Lu J, Schlanger R, Zhang H, Wang JY, Fox MC, Purton LE, Fleming HH, Cobb B, Merkenschlager M, Golub TR, Scadden DT: MicroRNA miR-125a controls hematopoietic stem cell number. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010, 107 (32): 14229-14234.

Qin B, Xiao B, Liang D, Xia J, Li Y, Yang H: MicroRNAs expression in ox-LDL treated HUVECs: MiR-365 modulates apoptosis and Bcl-2 expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011, 410 (1): 127-133.

Yang K, He YS, Wang XQ, Lu L, Chen QJ, Liu J, Sun Z, Shen WF: MiR-146a inhibits oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced lipid accumulation and inflammatory response via targeting toll-like receptor 4. FEBS Lett. 2011, 585 (6): 854-860.

Huang RS, Hu GQ, Lin B, Lin ZY, Sun CC: MicroRNA-155 silencing enhances inflammatory response and lipid uptake in oxidized low-density lipoprotein-stimulated human THP-1 macrophages. J Investig Med. 2010, 58 (8): 961-967.

Bonauer A, Carmona G, Iwasaki M, Mione M, Koyanagi M, Fischer A, Burchfield J, Fox H, Doebele C, Ohtani K, Chavakis E, Potente M, Tjwa M, Urbich C, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S: MicroRNA-92a controls angiogenesis and functional recovery of ischemic tissues in mice. Science. 2009, 324 (5935): 1710-1713.

Kuehbacher A, Urbich C, Dimmeler S: Targeting microRNA expression to regulate angiogenesis. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008, 29 (1): 12-15.

Cascio S, D'Andrea A, Ferla R, Surmacz E, Gulotta E, Amodeo V, Bazan V, Gebbia N, Russo A: miR-20b modulates VEGF expression by targeting HIF-1 alpha and STAT3 in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. J Cell Physiol. 2010, 224 (1): 242-249.

Fasanaro P, D'Alessandra Y, Di Stefano V, Melchionna R, Romani S, Pompilio G, Capogrossi MC, Martelli F: MicroRNA-210 modulates endothelial cell response to hypoxia and inhibits the receptor tyrosine kinase ligand Ephrin-A3. J Biol Chem. 2008, 283 (23): 15878-15883.

Liu XD, Wu X, Yin YL, Liu YQ, Geng MM, Yang HS, Blachier F, Wu GY: Effects of dietary L: -arginine or N-carbamylglutamate supplementation during late gestation of sows on the miR-15b/16, miR-221/222. 2011, Amino Acids: VEGFA and eNOS expression in umbilical vein

Esau C, Davis S, Murray SF, Yu XX, Pandey SK, Pear M, Watts L, Booten SL, Graham M, McKay R, Subramaniam A, Propp S, Lollo BA, Freier S, Bennett CF, Bhanot S, Monia BP: miR-122 regulation of lipid metabolism revealed by in vivo antisense targeting. Cell Metab. 2006, 3 (2): 87-98.

Nakanishi N, Nakagawa Y, Tokushige N, Aoki N, Matsuzaka T, Ishii K, Yahagi N, Kobayashi K, Yatoh S, Takahashi A, Suzuki H, Urayama O, Yamada N, Shimano H: The up-regulation of microRNA-335 is associated with lipid metabolism in liver and white adipose tissue of genetically obese mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009, 385 (4): 492-496.

Lanford RE, Hildebrandt-Eriksen ES, Petri A, Persson R, Lindow M, Munk ME, Kauppinen S, Orum H: Therapeutic silencing of microRNA-122 in primates with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Science. 2010, 327 (5962): 198-201.

Cox LA, Mahaney MC, Vandeberg JL, Rogers J: A second-generation genetic linkage map of the baboon (Papio hamadryas) genome. Genomics. 2006, 88 (3): 274-281.

Kleemann R, Verschuren L, van Erk MJ, Nikolsky Y, Cnubben NH, Verheij ER, Smilde AK, Hendriks HF, Zadelaar S, Smith GJ, Kaznacheev V, Nikolskaya T, Melnikov A, Hurt-Camejo E, van der Greef J, van Ommen B, Kooistra T: Atherosclerosis and liver inflammation induced by increased dietary cholesterol intake: a combined transcriptomics and metabolomics analysis. Genome Biol. 2007, 8 (9): R200-

McGill HC, McMahan CA, Kruski AW, Kelley JL, Mott GE: Responses of serum lipoproteins to dietary cholesterol and type of fat in the baboon. Arteriosclerosis. 1981, 1 (5): 337-344.

McGill HC, McMahan CA, Zieske AW, Tracy RE, Malcom GT, Herderick EE, Strong JP: Association of Coronary Heart Disease Risk Factors with microscopic qualities of coronary atherosclerosis in youth. Circulation. 2000, 102 (4): 374-379.

Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V: The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993, 75 (5): 843-854.

Vaz C, Ahmad HM, Sharma P, Gupta R, Kumar L, Kulshreshtha R, Bhattacharya A: Analysis of microRNA transcriptome by deep sequencing of small RNA libraries of peripheral blood. BMC Genomics. 2010, 11: 288-

Morin RD, O'Connor MD, Griffith M, Kuchenbauer F, Delaney A, Prabhu AL, Zhao Y, McDonald H, Zeng T, Hirst M, Eaves CJ, Marra MA: Application of massively parallel sequencing to microRNA profiling and discovery in human embryonic stem cells. Genome Res. 2008, 18 (4): 610-621.

t Hoen PA, Ariyurek Y, Thygesen HH, Vreugdenhil E, Vossen RH, de Menezes RX, Boer JM, van Ommen GJ, den Dunnen JT: Deep sequencing-based expression analysis shows major advances in robustness, resolution and inter-lab portability over five microarray platforms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36 (21): e141-

Felli N, Fontana L, Pelosi E, Botta R, Bonci D, Facchiano F, Liuzzi F, Lulli V, Morsilli O, Santoro S, Valtieri M, Calin GA, Liu CG, Sorrentino A, Croce CM, Peschle C: MicroRNAs 221 and 222 inhibit normal erythropoiesis and erythroleukemic cell growth via kit receptor down-modulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005, 102 (50): 18081-18086.

Maxwell KN, Soccio RE, Duncan EM, Sehayek E, Breslow JL: Novel putative SREBP and LXR target genes identified by microarray analysis in liver of cholesterol-fed mice. J Lipid Res. 2003, 44 (11): 2109-2119.

Cheng C, Tempel D, Den Dekker WK, Haasdijk R, Chrifi I, Bos FL, Wagtmans K, van de Kamp EH, Blonden L, Biessen EA, Moll F, Pasterkamp G, Serruys PW, Schulte-Merker S, Duckers HJ: Ets2 determines the inflammatory state of endothelial cells in advanced atherosclerotic lesions. Circ Res. 2011, 109 (4): 382-395.

Leeper NJ, Raiesdana A, Kojima Y, Chun HJ, Azuma J, Maegdefessel L, Kundu RK, Quertermous T, Tsao PS, Spin JM: MicroRNA-26a is a novel regulator of vascular smooth muscle cell function. J Cell Physiol. 2011, 226 (4): 1035-1043.

Quintavalle M, Elia L, Condorelli G, Courtneidge SA: MicroRNA control of podosome formation in vascular smooth muscle cells in vivo and in vitro. J Cell Biol. 2010, 189 (1): 13-22.

Ji R, Cheng Y, Yue J, Yang J, Liu X, Chen H, Dean DB, Zhang C: MicroRNA expression signature and antisense-mediated depletion reveal an essential role of MicroRNA in vascular neointimal lesion formation. Circ Res. 2007, 100 (11): 1579-1588.

Yang L, Duan R, Chen D, Wang J, Chen D, Jin P: Fragile X mental retardation protein modulates the fate of germline stem cells in Drosophila. Hum Mol Genet. 2007, 16 (15): 1814-1820.

Li T, Cao H, Zhuang J, Wan J, Guan M, Yu B, Li X, Zhang W: Identification of miR-130a, miR-27b and miR-210 as serum biomarkers for atherosclerosis obliterans. Clin Chim Acta. 2011, 412 (1–2): 66-70.

Fang Y, Shi C, Manduchi E, Civelek M, Davies PF: MicroRNA-10a regulation of proinflammatory phenotype in athero-susceptible endothelium in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010, 107 (30): 13450-13455.

Rayner KJ, Esau CC, Hussain FN, McDaniel AL, Marshall SM, van Gils JM, Ray TD, Sheedy FJ, Goedeke L, Liu X, Khatsenko OG, Kaimal V, Lees CJ, Fernandez-Hernando C, Fisher EA, Temel RE, Moore KJ: Inhibition of miR-33a/b in non-human primates raises plasma HDL and lowers VLDL triglycerides. Nature. 2011, 478 (7369): 404-407.

Fernandez-Hernando C, Moore KJ: MicroRNA modulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011, 31 (11): 2378-2382.

Vickers KC, Palmisano BT, Shoucri BM, Shamburek RD, Remaley AT: MicroRNAs are transported in plasma and delivered to recipient cells by high-density lipoproteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2011, 13 (4): 423-433.

Rader DJ, Cohen J, Hobbs HH: Monogenic hypercholesterolemia: new insights in pathogenesis and treatment. J Clin Invest. 2003, 111 (12): 1795-1803.

Friedlander MR, Chen W, Adamidi C, Maaskola J, Einspanier R, Knespel S, Rajewsky N: Discovering microRNAs from deep sequencing data using miRDeep. Nat Biotechnol. 2008, 26 (4): 407-415.

Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N: Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight?. Nat Rev Genet. 2008, 9 (2): 102-114.

Zhang C, Zheng H, Yu Q, Yang P, Li Y, Cheng F, Fan J, Liu E: A practical method for quantifying atherosclerotic lesions in rabbits. J Comp Pathol. 2010, 142 (2–3): 122-128.

Navarro A, Diaz T, Gallardo E, Vinolas N, Marrades RM, Gel B, Campayo M, Quera A, Bandres E, Garcia-Foncillas J, Ramirez J, Monzo M: Prognostic implications of miR-16 expression levels in resected non-small-cell lung cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2011, 103 (5): 411-415.

Porkka KP, Ogg EL, Saramaki OR, Vessella RL, Pukkila H, Lahdesmaki H, van Weerden WM, Wolf M, Kallioniemi OP, Jenster G, Visakorpi T: The miR-15a-miR-16-1 locus is homozygously deleted in a subset of prostate cancers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011, 50 (7): 499-509.

Feng ZT, Li J, Ren J, Lv Z: Expression of miR-146a and miR-16 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and their correlation to the disease activity. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2011, 31 (2): 320-323.

Kalimutho M, Di Cecilia S, Del Vecchio Blanco G, Roviello F, Sileri P, Cretella M, Formosa A, Corso G, Marrelli D, Pallone F, Federici G, Bernardini S: Epigenetically silenced miR-34b/c as a novel faecal-based screening marker for colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011, 104 (11): 1770-1778.

Minones-Moyano E, Porta S, Escaramis G, Rabionet R, Iraola S, Kagerbauer B, Espinosa-Parrilla Y, Ferrer I, Estivill X, Marti E: MicroRNA profiling of Parkinson's disease brains identifies early downregulation of miR-34b/c which modulate mitochondrial function. Hum Mol Genet. 2011, 20 (15): 3067-3078.

Toyota M, Suzuki H, Sasaki Y, Maruyama R, Imai K, Shinomura Y, Tokino T: Epigenetic silencing of microRNA-34b/c and B-cell translocation gene 4 is associated with CpG island methylation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2008, 68 (11): 4123-4132.

Hafizi S, Ibraimi F, Dahlback B: C1-TEN is a negative regulator of the Akt/PKB signal transduction pathway and inhibits cell survival, proliferation, and migration. FASEB J. 2005, 19 (8): 971-973.

Jung CH, Hansen MA, Makunin IV, Korbie DJ, Mattick JS: Identification of novel non-coding RNAs using profiles of short sequence reads from next generation sequencing data. BMC Genomics. 2010, 11: 77-

Ender C, Krek A, Friedlander MR, Beitzinger M, Weinmann L, Chen W, Pfeffer S, Rajewsky N, Meister G: A human snoRNA with microRNA-like functions. Mol Cell. 2008, 32 (4): 519-528.

Sempere LF, Freemantle S, Pitha-Rowe I, Moss E, Dmitrovsky E, Ambros V: Expression profiling of mammalian microRNAs uncovers a subset of brain-expressed microRNAs with possible roles in murine and human neuronal differentiation. Genome Biol. 2004, 5 (3): R13-

Agueli C, Cammarata G, Salemi D, Dagnino L, Nicoletti R, La Rosa M, Messana F, Marfia A, Bica MG, Coniglio ML, Pagano M, Fabbiano F, Santoro A: 14q32/miRNA clusters loss of heterozygosity in acute lymphoblastic leukemia is associated with up-regulation of BCL11a. Am J Hematol. 2010, 85 (8): 575-578.

Patz M, Pallasch CP, Wendtner CM: Critical role of microRNAs in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: overexpression of the oncogene PLAG1 by deregulated miRNAs. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010, 51 (8): 1379-1381.

Voorhoeve PM, le Sage C, Schrier M, Gillis AJ, Stoop H, Nagel R, Liu YP, van Duijse J, Drost J, Griekspoor A, Zlotorynski E, Yabuta N, De Vita G, Nojima H, Looijenga LH, Agami R: A genetic screen implicates miRNA-372 and miRNA-373 as oncogenes in testicular germ cell tumors. Cell. 2006, 124 (6): 1169-1181.

Murray MJ, Saini HK, van Dongen S, Palmer RD, Muralidhar B, Pett MR, Piipari M, Thornton CM, Nicholson JC, Enright AJ, Coleman N: The two most common histological subtypes of malignant germ cell tumour are distinguished by global microRNA profiles, associated with differential transcription factor expression. Mol Cancer. 2010, 9: 290-

Palmer RD, Murray MJ, Saini HK, van Dongen S, Abreu-Goodger C, Muralidhar B, Pett MR, Thornton CM, Nicholson JC, Enright AJ, Coleman N: Children's Cancer and Leukaemia Group: Malignant germ cell tumors display common microRNA profiles resulting in global changes in expression of messenger RNA targets. Cancer Res. 2010, 70 (7): 2911-2923.

Altuvia Y, Landgraf P, Lithwick G, Elefant N, Pfeffer S, Aravin A, Brownstein MJ, Tuschl T, Margalit H: Clustering and conservation patterns of human microRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33 (8): 2697-2706.

Bentwich I: Prediction and validation of microRNAs and their targets. FEBS Lett. 2005, 579 (26): 5904-5910.

Freemerman AJ, Wright RM, Flickinger CJ, Herr JC: Cloning and sequencing of baboon and cynomolgus monkey intra-acrosomal protein SP-10: homology with human SP-10 and a mouse sperm antigen (MSA-63). Mol Reprod Dev. 1993, 34 (2): 140-148.

Richardson K, Louie-Gao Q, Arnett DK, Parnell LD, Lai CQ, Davalos A, Fox CS, Demissie S, Cupples LA, Fernandez-Hernando C, Ordovas JM: The PLIN4 variant rs8887 modulates obesity related phenotypes in humans through creation of a novel miR-522 seed site. PLoS One. 2011, 6 (4): e17944-

Kajimoto K, Naraba H, Iwai N: MicroRNA and 3 T3-L1 pre-adipocyte differentiation. RNA. 2006, 12 (9): 1626-1632.

Lin Q, Gao Z, Alarcon RM, Ye J, Yun Z: A role of miR-27 in the regulation of adipogenesis. FEBS J. 2009, 276 (8): 2348-2358.

Rainwater DL, Cox LA, Rogers J, VandeBerg JL, Mahaney MC: Localization of multiple pleiotropic genes for lipoprotein metabolism in baboons. J Lipid Res. 2009, 50 (7): 1420-1428.

Skogsberg J, Lundstrom J, Kovacs A, Nilsson R, Noori P, Maleki S, Kohler M, Hamsten A, Tegner J, Bjorkegren J: Transcriptional profiling uncovers a network of cholesterol-responsive atherosclerosis target genes. PLoS Genet. 2008, 4 (3): e1000036-

Yamakawa K, Yanagi H, Saku K, Sasaki J, Okafuji T, Shimakura Y, Kawai K, Tsuchiya S, Takada K, Naito S: Family studies of the LDL receptor gene of relatively severe hereditary hypercholesterolemia associated with Achilles tendon xanthomas. Hum Genet. 1991, 86 (5): 445-449.

Pauciullo P, Giannino A, De Michele M, Gentile M, Liguori R, Argiriou A, Carlotto A, Faccenda F, Mancini M, Bond MG, De Simone V, Rubba P: Increased carotid artery intima-media thickness is associated with a novel mutation of low-density lipoprotein receptor independently of major cardiovascular risk factors. Metabolism. 2003, 52 (11): 1433-1438.

Yuan G, Liu Y, Sun T, Xu Y, Zhang J, Yang Y, Zhang M, Cianflone K, Wang DW: The therapeutic role of very low-density lipoprotein receptor gene in hyperlipidemia in type 2 diabetic rats. Hum Gene Ther. 2011, 22 (3): 302-312.

Wild PS, Zeller T, Schillert A, Szymczak S, Sinning CR, Deiseroth A, Schnabel RB, Lubos E, Keller T, Eleftheriadis MS, Bickel C, Rupprecht HJ, Wilde S, Rossmann H, Diemert P, Cupples LA, Perret C, Erdmann J, Stark K, Kleber ME, Epstein SE, Voight BF, Kuulaasma K, Li M, Schafer AS, Klopp N, Braund PS, Sager HB, Demissie S, Proust C, Konig IR, Wichmann HE, Reinhard W, Hoffmann MM, Virtamo J, Burnett MS, Siscovick D, Wiklund PG, Qu L, El Mokthari NE, Thompson JR, Peters A, Smith AV, Yon E, Baumert J, Hengstenberg C, Marz W, Amouyel P, Devaney J, Schwartz SM, Saarela O, Mehta NN, Rubin D, Silander K, Hall AS, Ferrieres J, Harris TB, Melander O, Kee F, Hakonarson H, Schrezenmeir J, Gudnason V, Elosua R, Arveiler D, Evans A, Rader DJ, Illig T, Schreiber S, Bis JC, Altshuler D, Kavousi M, Witteman JC, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, Folsom AR, Barbalic M, Boerwinkle E, Kathiresan S, Reilly MP, O'Donnell CJ, Samani NJ, Schunkert H, Cambien F, Lackner KJ, Tiret L, Salomaa V, Munzel T, Ziegler A, Blankenberg S: A Genome-wide Association Study Identifies LIPA as a Susceptibility Gene for Coronary Artery Disease. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2011, 4 (4): 403-U203.

Hafizi S, Gustafsson A, Oslakovic C, Idevall-Hagren O, Tengholm A, Sperandio O, Villoutreix BO, Dahlback B: Tensin2 reduces intracellular phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate levels at the plasma membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010, 399 (3): 396-401.

Toma I, McCaffrey TA: Transforming growth factor-beta and atherosclerosis: interwoven atherogenic and atheroprotective aspects. Cell Tissue Res. 2011, 1007/s00441-011-1189-3. PMID: 21626289

Ding J, Wang DZ: "RISCing" the heart: In vivo identification of cardiac microRNA targets by RISCome. Circ Res. 2011, 108 (1): 3-5.

Xiao F, Zuo Z, Cai G, Kang S, Gao X, Li T: miRecords: an integrated resource for microRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37 (Database issue): D105-10.

Hanina SA, Mifsud W, Down TA, Hayashi K, O'Carroll D, Lao K, Miska EA, Surani MA: Genome-wide identification of targets and function of individual MicroRNAs in mouse embryonic stem cells. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6 (10): e1001163-

Karginov FV, Conaco C, Xuan Z, Schmidt BH, Parker JS, Mandel G, Hannon GJ: A biochemical approach to identifying microRNA targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007, 104 (49): 19291-19296.

Matkovich SJ, Van Booven DJ, Eschenbacher WH, Dorn GW: RISC RNA sequencing for context-specific identification of in vivo microRNA targets. Circ Res. 2011, 108 (1): 18-26.

Cox LA, Birnbaum S, Mahaney MC, Rainwater DL, Williams JT, VandeBerg JL: Identification of promoter variants in baboon endothelial lipase that regulate high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. Circulation. 2007, 116 (10): 1185-1195.

Kammerer CM, Rainwater DL, Cox LA, Schneider JL, Mahaney MC, Rogers J, VandeBerg JL: Locus controlling LDL cholesterol response to dietary cholesterol is on baboon homologue of human chromosome 6. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002, 22 (10): 1720-1725.

Rainwater DL, Kammerer CM, Hixson JE, Carey KD, Rice KS, Dyke B, VandeBerg JF, Slifer SH, Atwood LD, McGill HC, Vandeberg JL: Two major loci control variation in beta-lipoprotein cholesterol and response to dietary fat and cholesterol in baboons. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998, 18 (7): 1061-1068.

Singh AT, Rainwater DL, Kammerer CM, Sharp RM, Poushesh M, Shelledy WR, VandeBerg JL: Dietary and genetic effects on LDL size measures in baboons. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996, 16 (12): 1448-1453.

Zhu E, Zhao F, Xu G, Hou H, Zhou L, Li X, Sun Z, Wu J: mirTools: microRNA profiling and discovery based on high-throughput sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38 (Web Server issue): W392-7.

Li R, Li Y, Kristiansen K, Wang J: SOAP: short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics. 2008, 24 (5): 713-714.

Griffiths-Jones S, Saini HK, van Dongen S, Enright AJ: miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36 (Database issue): D154-8.

Griffiths-Jones S: Annotating non-coding RNAs with Rfam. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2005, 0.1002/0471250953.bi1205s9. PMID: 18428745

Tarailo-Graovac M, Chen N: Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2009, 10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25. PMID: 19274634

Hofacker IL, Stadler PF: Memory efficient folding algorithms for circular RNA secondary structures. Bioinformatics. 2006, 22 (10): 1172-1176.

Storey JD, Tibshirani R: Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003, 100 (16): 9440-9445.

Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Bartel DP: MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell. 2007, 27 (1): 91-105.

Acknowledgements and funding

We thank Dr. Kimberly D. Spradling for assistance in data analysis and manuscript proofreading, Ms. Jane VandeBerg for assistance in measurements of serum LDL-C concentrations in baboons, and Mr. Roy Garcia for sequencing the small RNA libraries. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants P01 HL028972-27, P01 HL028972-27 S1 and P51 RR013986. This investigation was conducted in part in facilities constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program Grant Number C06 RR013556 and C06 RR015456 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. Genesio Karere is a recipient of a research grant in 2009 from the Southwest Foundation Forum Research Support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GMK, JPG and LAC participated in the conception and design of the experiments and performed data analyses. All authors contributed to writing this manuscript and all have read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12864_2011_4543_MOESM1_ESM.xls

Additional file 1: A Microsoft Excel file containing human ortholog miRNAs expressed in livers of low and high LDL-C baboons on chow and HCHF diets.(XLS 1 MB)

12864_2011_4543_MOESM2_ESM.xls

Additional file 2: A Microsoft Excel file containing baboon novel mRNAs expressed in livers of low and high LDL-C baboons on chow and HCHF diets.(XLS 151 KB)

12864_2011_4543_MOESM4_ESM.xls

Additional file 4: A Microsoft Excel file containing expressed other non-coding RNAs in response to HCHF diet in high LDL-C baboon livers.(XLS 865 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Karere, G.M., Glenn, J.P., VandeBerg, J.L. et al. Differential microRNA response to a high-cholesterol, high-fat diet in livers of low and high LDL-C baboons. BMC Genomics 13, 320 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-13-320

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-13-320