Abstract

Background

Cucumber, Cucumis sativus L., is an economically and nutritionally important crop of the Cucurbitaceae family and has long served as a primary model system for sex determination studies. Recently, the sequencing of its whole genome has been completed. However, transcriptome information of this species is still scarce, with a total of around 8,000 Expressed Sequence Tag (EST) and mRNA sequences currently available in GenBank. In order to gain more insights into molecular mechanisms of plant sex determination and provide the community a functional genomics resource that will facilitate cucurbit research and breeding, we performed transcriptome sequencing of cucumber flower buds of two near-isogenic lines, WI1983G, a gynoecious plant which bears only pistillate flowers, and WI1983H, a hermaphroditic plant which bears only bisexual flowers.

Result

Using Roche-454 massive parallel pyrosequencing technology, we generated a total of 353,941 high quality EST sequences with an average length of 175bp, among which 188,255 were from gynoecious flowers and 165,686 from hermaphroditic flowers. These EST sequences, together with ~5,600 high quality cucumber EST and mRNA sequences available in GenBank, were clustered and assembled into 81,401 unigenes, of which 28,452 were contigs and 52,949 were singletons. The unigenes and ESTs were further mapped to the cucumber genome and more than 500 alternative splicing events were identified in 443 cucumber genes. The unigenes were further functionally annotated by comparing their sequences to different protein and functional domain databases and assigned with Gene Ontology (GO) terms. A biochemical pathway database containing 343 predicted pathways was also created based on the annotations of the unigenes. Digital expression analysis identified ~200 differentially expressed genes between flowers of WI1983G and WI1983H and provided novel insights into molecular mechanisms of plant sex determination process. Furthermore, a set of SSR motifs and high confidence SNPs between WI1983G and WI1983H were identified from the ESTs, which provided the material basis for future genetic linkage and QTL analysis.

Conclusion

A large set of EST sequences were generated from cucumber flower buds of two different sex types. Differentially expressed genes between these two different sex-type flowers, as well as putative SSR and SNP markers, were identified. These EST sequences provide valuable information to further understand molecular mechanisms of plant sex determination process and forms a rich resource for future functional genomics analysis, marker development and cucumber breeding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) is an economically and nutritionally important vegetable crop cultivated world-wide and belongs to the Cucurbitaceae family which includes several other important vegetable crops such as melon, watermelon, squash and pumpkin. Cucumber has considerable impact on human nutrition and is among 35 fruits, vegetables, and herbs identified by the National Cancer Institute as having cancer-protective properties. Cucumber and melon have long served as the primary model systems for sex determination studies due to their diverse floral sex types [1]. Sex determination in flowering plants is a fundamental developmental process of great economical importance. Sex determination occurs by the selective arrest of either the male stamen or female carpel during development [2]. Sex expression in cucurbit species can be regulated by plant hormones and environmental factors [1]. Ethylene is highly correlated with the femaleness and has been regarded as the primary sex determination factor [3, 4]. Early genetics studies indicated that there are three major sex-determining genes in cucumber and melon: F, A, and M [5]. Recently, the A gene in melon and the M gene in cucumber have been cloned and both encode 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase (ACS), which is a key enzyme in ethylene biosynthesis [6, 7]. In cucumber, a series of evidences strongly support that the F gene also encodes an ACS [8, 9]. Despite such advances, the molecular mechanisms of sex expression in cucurbit species still remain largely unknown.

Cucumber is a diploid species with seven pairs of chromosomes (2n = 14). The cucumber genome is relatively small, with an estimated size of 367 Mb [10], which is similar to rice (389 Mb; [11]), and approximately three times the size of the model species Arabidopsis thaliana (125 Mb; [12]). Despite its economical and nutritional importance and the relatively small genome size, currently available genomic and genetic tools for cucumber are very limited. These combined with the fact that the genetic diversity of cucumber is very narrow are major factors limiting cucumber breeding. For the past 10 years, the average yields of both fresh and processing cucumbers have remained virtually unchanged in the United States [13]. Therefore, in order to develop improved crops, it is necessary to develop new resources that can be used to identify novel molecular markers that are linked to the trait of interest.

Recently the whole genome sequencing of the domestic cucumber, C. sativus var. sativus L., has been completed using a hybrid approach by combining traditional Sanger and next-generation Illumina GA sequencing technologies [14]. The completion of cucumber whole genome sequencing provides tremendous opportunities for evolutionary and comparative genomics analysis and facilitates the identification of key genes of economical and biological interests. Complementary to the whole genome sequences, Expressed Sequenced Tags (ESTs) present an alternative valuable resource for research and breeding as they provide the most comprehensive information regarding the dynamics of cucumber transcriptome. It has been reported that ESTs have played significant roles in accelerating gene discovery including gene family expansion [15, 16], improving genome annotation [17], elucidating phylogenetic relationships [18], facilitating breeding programs for both plants and animals by providing SSR and SNP markers [19, 20], and large-scale expression analysis [21, 22]. In addition, ESTs are a robust method for rapid identification of transcripts involved in specific biological processes. Currently there are more than 64 million ESTs in the NCBI public collection, dbEST database [23]. However, only around 8,000 EST sequences are available for cucumber and approximately 150,000 for all the species in the Cucurbitaceae family, of which ~50,000 are in the dbEST database and ~100,000 recently generated melon ESTs are available in the Cucurbit Genomics Database [24], as compared to more than 1.5 and 2 million ESTs available for Arabidopsis and maize, respectively.

Recent advances in next-generation sequencing technologies allow us to generate large scale ESTs efficiently and cost-effectively. In this study, we report the generation of more than 350,000 high quality cucumber ESTs from flower buds of two near-isogenic lines, a gynoecious plant (MMFF) which bears only female flowers and a hermaphroditic plant (mmFF) which bears bisexual flowers, using Roche-454 massive parallel pyrosequencing technology. These ESTs, together with ~5,600 high quality cucumber EST and mRNA sequences available in public domains, were clustered and assembled into 81,401 unigenes, which were further aligned to cucumber genome predicted genes and annotated extensively in this study. We then performed comparative digital expression profiling analysis to systematically characterize the differences of mRNA expression levels between the two flowers with different sex types, in an attempt to identify genes playing roles in cucumber sex determination. Furthermore, putative SNP and SSR markers were identified from these ESTs.

Results and discussion

Cucumber EST sequence generation and assembly

We performed a half 454 GS-FLX run on each of the two flower bud samples which were collected from two near-isogenic lines, a gynoecious line (WI1983G; MMFF) which bears only female flowers and a hermaphroditic line (WI1983H; mmFF) which bears only bisexual flowers. We obtained a total of approximately 405,000 raw reads. After removing low quality regions, adaptors and all possible contaminations, we obtained a total of 353,941 high quality ESTs with an average length of 175 bp and a total length of 61.9 Mb, among which 188,255 were from WI1983G and 165,686 from WI1983H (Table 1). The length distribution of these high quality ESTs is shown in Figure 1A. Despite a significant number of ESTs were very short (<100), more than 80% fell between 100 and 300 bp in length.

The ESTs generated in this study, together with 5,196 high quality ESTs and 420 mRNA sequences available in GenBank, were subjected to cluster and assembly analyses. A total of 81,401 unigenes were obtained, among which 28,452 were contigs and 52,949 were singletons. The unigenes had an average length of 231.5 bp and a total length of approximately 18.8 Mb (Table 2). The length distributions of singletons, contigs and unigenes, respectively, are shown in Figure 1B, revealing that more than 8,000 contigs are greater than 400 bp, while only around 400 singletons are greater than 400 bp.

The distribution of the number of ESTs in cucumber unigenes is shown in Figure 2. From our EST collection, we were able to identify a number of highly abundant transcripts in cucumber flowers. Around 4,400 transcripts have more than 10 EST members and these 4,400 transcripts (~5% of all the unigenes) contain ~62% of the EST reads.

Alternative Splicing in Cucumber

Alternative splicing (AS) is an important regulatory mechanism in higher organisms and plays a major role in the generation of proteomic and functional diversities [25]. In plants, a wide range of processes including development, stress response and disease resistance are regulated by AS [26–28]. Currently AS of several model plant organisms including Arabidopsis and rice has been characterized at the genome scale [29, 30] while AS in cucumber has not yet been investigated.

To identify AS events in cucumber genome, we mapped all cucumber ESTs to the genome predicted gene regions. We were able to identify a total of 25,917 unique intron-exon junction sites in 8,355 genes. Among these junction sites, 20,692 (80%) were consistent with those predicted from cucumber genome. A total of 530 AS events were identified in 443 cucumber genes based on the junction sites derived from EST-genome alignments (Additional file 1). These AS events were further classified into five different types: alternative 5' splice site (AltD), alternative 3' splice site (AltA), alternative position (AltP), intron retention (IntronR) and exon skipping (ExonS). Intron retention is the most prevalent AS type, comprising 55.7% of all AS events and 54.4% of all alternatively spliced genes identified in cucumber (Table 3). This is consistent with previous reports in Arabidopsis and Rice [30, 31]. The relatively small number of genes were identified to have AS events in this study is probably due to the limited number of ESTs and the short length of 454 sequences, most of which were aligned entirely to single exons and did not cover the intron-exon junction sites. More RNA-seq data, especially those from different tissues and conditions, are required in order to obtain a more complete picture of alternative splicing in cucumber. The alignments of ESTs on the cucumber genome can be viewed on the cucumber genome browser in the Cucurbit Genomics Database [24].

Mapping unigenes to cucumber genome predicted genes

We further aligned cucumber unigenes to cucumber genome predicted genes. Around 72% (58,524) unigenes could be mapped, allowing 95% sequence identity and 80% length coverage (Table 2). The unmappable unigenes (22,877; 28%) in cucumber might include non-coding RNAs, fusion transcripts, relatively short and low quality singletons, UTR sequences far from the translation start or stop sites (>1000 bp), and those having incomplete coverage by the genome. It has been reported that even in Arabidopsis around 13% of the 454 ESTs can't be aligned to the predicted genes [32] and in human only 64% of the 454 reads can be mapped to the RefSeq database of well annotated human genes [33]. All the mapping results were provided in the Cucurbit Genomics Database [24]

Out of 26,682 genes predicted from the cucumber genome [14], approximately 64% (17,087) were represented by this EST collection. In addition, based on the transcript assembly described above, we found that cucumber ESTs generated in this study covered ~70% (2,625/3,772, Table 2) of genes derived from GenBank ESTs and mRNAs which were generated from various different tissues including flower, fruit and leaf. Furthermore, we compared the Arabidopsis protein sequences against cucumber unigenes using the blast program with an e-value cutoff of 1e-10 and found that ~67% of all the Arabidopsis protein sequences had at least one matching cucumber unigene. Microarray analysis in Arabidopsis indicates that 55-67% genes are expressed in a single sample [34] and studies in human and mouse also indicate that around 60-70% genes are expressed in a specific tissue [35]. All the above results indicated that the ESTs generated under the present study captured the majority of genes expressed in cucumber flower buds. These ESTs represented a significant addition to the existing cucurbit genomic resources.

Functional annotation of cucumber transcriptome

Based on the alignments of unigenes to cucumber genome predicted genes, a total of 39,964 unique genes were obtained, including 17,087 that contained cucumber genome predicted genes and 22,877 unmappable unigenes. We named these unique genes as virtual unigenes. To infer putative functions of cucumber virtual unigenes, we compared their sequences against GenBank non-redundant protein database (nr) with an e value cutoff of 1e-5. The analysis indicated that 20,023 (50.1%) virtual unigenes had significant matches in the nr database, among which 15,126 were cucumber genome predicted genes (88.5% of the 17,087 EST-matched predicted genes) and 4,897 unmappable unigenes (21.4% of all unmappable unigenes). The low percentage (21.4%) of cucumber unmappable unigenes that can be assigned a putative function might be mainly due to the short sequence reads generated by the 454 sequencing technology and the relatively short sequences of the resulting unigenes (Table 1 and 2), most of which probably lack the conserved functional domains. Another possible reason is that some of these unigenes might be non-coding RNAs.

Gene Ontology (GO) terms were further assigned to cucumber virtual unigenes based on their sequence similarities to known proteins in the UniProt database annotated with GO terms as well as InterPro and Pfam domains they contain. A total of 15,901 virtual unigenes (39.8%) were assigned at least one GO term, among which 13,620 were assigned at least one GO term in the biological process category, 13,799 in the molecular function category and 12,982 in the cellular component category. These virtual unigenes were further classified into different functional categories using a set of plant-specific GO slims, which are a list of high-level GO terms providing a broad overview of the ontology content [36]. Figure 3 shows the functional classification of cucumber virtual unigenes into plant specific GO slims within the biological process category. Cellular process, metabolic process, and biosynthetic process were among the most highly represented groups, indicating the flower buds were undergoing rapid growth and extensive metabolic activities. It is worth noting that GO annotations revealed 417 and 129 genes involved in flower development and the pollination process, respectively. Genes involved in other important biological processes such as stress response, signal transduction, and cell differentiation were also identified through GO annotations.

Biochemical pathways

To further demonstrate the usefulness of cucumber ESTs generated in the present study, we identified biochemical pathways represented by the EST collection. Annotations of cucumber unigenes were fed into the Pathway Tools [37] and this process predicted a total of 343 pathways represented by a total of 5,342 unigenes, which belonged to 1,407 virtual unigenes. These predicted pathways represented the majority of plant biochemical pathways for compound biosynthesis, degradation, utilization, and assimilation, and pathways involved in the processes of detoxification and generation of precursor metabolites and energy. A database containing all the predicted cucumber pathways has been developed and is available through the Cucubit Genomics Database [24].

Enzymes catalyzing almost all steps in several major plant metabolic pathways including Calvin cycle, glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, pentose phosphate pathway, and several important secondary metabolite biosynthesis pathways including carotenoid biosynthesis and flavonoid and anthocyanin biosynthesis, could be represented by unigenes derived from the cucumber EST collection. Moreover, genes encoding oxidosqualene cyclase, an enzyme in the cucurbitacin biosynthesis pathway, were also found in the EST collection. All these evidences supported that the ESTs generated under this study provided a valuable resource for cucumber gene discovery and future functional analysis.

Comparison of transcriptomes between gynoecious and hermaphroditic flowers

Cucumber is a model system for sex determination studies due to its diverse floral sex types [1]. During the past several years, significant progresses have been made in elucidating the mechanisms of plant sex determination, an important and fundamental developmental process of flowering plants, as exemplified by cloning several major sex-determining genes in cucurbit species [6, 7, 38]. Despite such advances, little is known about transcriptome dynamics of flowers with different sex types. In the present study, we systematically compared transcriptome dynamics between flowers of two isogenic lines, a gynoecious plant and a hermaphroditic plant, using a digital expression profiling approach.

Digital expression profiling, also called tag sampling or RNA-seq, has been proved to be a powerful and efficient approach for gene expression analysis at the genome level [39] and offers several advantages over microarray technologies (See review in [40]). Due to the rapid advances in next generation sequencing technologies, the digital expression profiling approach becomes more and more widely used. It has been reported that with EST collections as small as 1,000 reads, quantitative expression data for numerous moderately and highly expressed genes can be generated [21, 41, 42]. SAGE, which is also a tag-count based gene expression analysis technology and has been widely used for transcriptome profiling study, usually collects 50,000 to 100,000 short tags for each sample [43]. In the present study, we collected more than 160,000 tags for each of the two samples (Table 1), providing sufficient coverage to identify the majority of genes of interest.

Our digital expression profiling analysis identified a total of 214 differentially expressed genes, among which 90 showed higher expression in gynoecious flowers and 124 showed higher expression in hermaphroditic flowers (Additional file 2). Few transcription factors other than a maize DELLA protein D8 [44] and a melon zinc finger protein CmWIP1 [38] have been functionally associated with the plant sex determination process. In this study we identified five transcription factors showing significantly higher expression in gynoecious flowers and six showing significantly higher expression in hermaphroditic flowers (Additional file 2).

Recently a C2H2 zinc-finger transcription factor in melon, CmWIP1, has been cloned and expression of CmWIP1 leads to carpel abortion, resulting in the development of unisexual male flowers [38]. In the present study, two zinc finger transcription factors (CU23681 and CU13995) were found to have higher expression in hermaphroditic flowers. They belong to different zinc finger transcription factor families from that of CmWIP1, as CU23681 belonging to the C2C2-GATA family and CU13995 to the VOZ family.

It has been reported that auxin can induce pistillate flower formation through its stimulation of ethylene production [45]. An Aux/IAA transcription factor (CU29035) was found to have higher expression in hermaphroditic flowers. Aux/IAA genes are early auxin responsive genes and their proteins function as active repressors of secondary auxin responsive genes [46]. Lower expression of the Aux/IAA gene in gynoecious flowers could result in higher expression of secondary auxin responsive genes thus induce femaleness. Consistent with this, an auxin-induced protein (CU23408) showed higher expression in gynoecious flowers in the present study.

Brassinosteroids (BRs) can induce femaleness in cucumber and this induction could be mediated, at least in part, by brassinosteroid-induced production of ethylene [47]. In the present study, a gene (CU27987) belonging to the BZR1-BES1 family showed higher expression in hermaphroditic flowers. BZR1-BES1 family proteins represent a novel class of plant transcription factors and are key components of the BR signaling pathway [48]. In Arabidopsis, BZR1 serves as a positive regulator of the BR signaling pathway, with a role in feedback regulation of BR biosynthesis [49]. It's worth noting that two additional genes involved in BR signaling also showed higher expression in hermaphroditic flowers. One is BRI1 (CU14635), a receptor of BRs [50]. The other (CU3495) encodes a BRI1-associated receptor kinase. In Arabidopsis, the gene has been reported to interact with BRI1 and modulate BR signaling [51, 52].

In Drosophila, a MYC transcription factor, daughterless (DA), provides an essential maternal component in the control of sex determination [53]. However, the role of MYC transcription factors in plant sex determination has not been documented. We found that a MYC transcription factor (CU12949) showed higher expression in hermaphroditic flowers.

Other putative transcription factors identified in this study, such as BEL1-like homeodomain protein, bHLH protein, WRKY DNA-binding protein, and NAC domain protein, have been found to regulate various processes of plant development, while a relationship between these transcription factors and plant sex determination has not been previously documented. In addition, among the genes differentially expressed in the two different sex-type flowers are several protein kinases. The correlation of transcription factors and protein kinases with sex determination suggested a pool of putative regulatory elements for future functional analysis. Furthermore, a large number of genes that have not associated with plant sex determination before were differentially expressed, suggesting additional pool of genes for further analysis.

Over-represented biological processes in differentially expressed genes

We further identified GO terms in the biological process category that were over-represented in the lists of genes showing higher expression in gynoecious and hermaphroditic flowers, respectively (Table 4 and 5). These GO terms serve as indications of significantly different biological processes undergoing in flowers of the two different genotypes. GO terms including biopolymer metabolic process, cellular biopolymer metabolic process, cellular macromolecule metabolic process, macromolecule metabolic process, and primary metabolic process, were enriched in both lists of genes, indicating that same biological processes could require different sets of genes during gynoecious and hermaphroditic flower development to maintain their activities. However, striking differences were found between these two lists of enriched GO terms. It is worth noting that GO terms related to responses to different kinds of abiotic/biotic stresses were highly enriched in genes showing higher expression in gynoecious flowers. It has been reported that a number of environment variables, such as light, temperature, water stress, and disease, as well as exogenous treatment of hormones or other growth-regulating substances, can directly influence plant sex expression [54, 55]. Factors including low temperature, low levels of light intensity, short-day treatment, low levels of carbon monoxide in the atmosphere, and exogenous application of auxins can promote cucumber female and depress male sex expression [54]. The results obtained from the present study could provide molecular cues underlying the effects of environmental factors on cucumber sex expression. Differences of other enriched GO terms included translation and system development that were enriched in genes showing higher expression in gynoecious flowers, and proteolysis and chromatin and chromosome organization that were enriched in genes showing higher expression in hermaphroditic flowers (Table 4 and 5). However, further studies are required to determine whether these biological processes are related to flower sex determinations.

Identification of Simple Sequence Repeats (SSRs) and Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs)

Both SSRs and SNPs are valuable markers for plant breeding programs. It has been reported that approximately 3-7% of expressed genes contain putative SSR motifs, mainly within the un-translated regions of the mRNA [56]. SSR markers derived from EST sequences have been extensively used in constructing genetic maps of cucurbit species [20, 57]. In the present study, we performed a general screen on the cucumber unigene dataset for the presence of SSRs. A total of 3,130 SSRs were found in 2,860 unigenes, whereas only 56 SSRs were found in unigenes containing only GenBank sequences. We excluded mononucleotide SSRs in our analysis because of the common homopolymer errors found in 454 sequencing data. The major types of the identified SSRs were trinucleotide (1,556) and dinucleotide (1,413), followed by tetranucleotide (89), pentanucleotide (46) and hexanucleotide (26). The most frequent SSR motif is AAG/CTT (769), followed by AG/CT (726), AT/TA (547) and AAT/ATT (204). Of the 2,860 SSR-containing unigenes, 1,679 (59%) had sufficient flanking sequences for primer design. The complete list of SSRs and their corresponding primer pair information were provided in Additional file 3.

Since the ESTs generated under the present study using the 454 technology are from two different cultivars, we expect SNPs to be present in our EST collection. We identified a total of 114 SNPs between WI1983G and WI1983H, among which 42 were transitions, 16 were transversions, and 56 were indels (Additional file 4). The frequency of SNP occurrence in our EST collection is relatively low, which is not unexpected since the sequences were derived from two near-isogenic lines.

In summary, the SSRs and SNPs identified in this study provided a valuable resource for future studies on genetic linkage mapping and the analysis of interesting traits in cucumber.

Conclusion

In this study, we describe the generation of more than 350,000 cucumber cDNA sequences from flower buds of two near-isogenic lines with different floral sex types, a gynoecious line and a hermaphroditic line, using the rapid and cost-effective massive parallel pyrosequencing technology. Currently in public domains, only ~8,000 ESTs are available for cucumber and ~150,000 for all the cucurbit species. The ESTs generated in the present study represent a significant addition to the existing genomics and functional genomics resources of cucurbit species. These ESTs have been used to facilitate the annotation of cucumber genome [14] and to identify alternatively spliced genes. In addition, these ESTs can also be served as a valuable source to derive SSR and SNP markers, which can help to further identify genes linked to interesting traits. A biochemical pathway database containing more than 300 predicted metabolite pathways was derived from these EST sequences. Digital expression analysis by comparing transcriptomes of two sex-type flowers provided some novel insights into the molecular mechanisms of cucumber sex determination, as well as a rich list of candidate genes for further functional analysis. To facilitate public usages of this EST resource, all the EST sequences, annotations, their alignments to the cucumber genome, and the derived pathway database have been made available in a searchable manner through the Cucurbit Genomics Database [24].

Methods

Plant material

Seeds of gynoecious (Cucumis sativus L. var sativus cv WI1983G; MMFF) and hermaphrodite (C. sativus L. var sativus cv WI1983H; mmFF) nearly isogenic cucumber lines were kindly provided by Dr J. E. Staub (University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA). WI1983G originated from a cross between inbred WI5821 and WI5822 [58]. An andromonoecious near-isogenic line WI1983A (mmff) was developed using a hermaphrodite line as the donor parent. Five direct backcrosses to WI1983G were made followed by three subsequent generations of self-pollination. The hermaphrodite WI1983H line was selected from a cross between WI1983G and WI1983A [59]. Seeds were germinated and grown in trays containing a soil mixture (peat: sand: pumice, 1:1:1, v/v/v). Plants were adequately watered and grown at day/night temperatures of 24/18°C with a 16-h photoperiod. Flower buds of approximately 5 mm in diameter, which represents a critical stage of cucumber sex determination [60], were collected from both lines and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen flower buds were stored at -80°C till use.

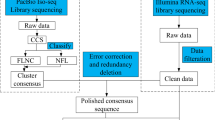

cDNA preparation and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from cucumber flower buds using the TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, USA). mRNA was purified from the total RNA using the Oligotex mRNA Midi Kit (QIAGEN, Germany). Double-strand cDNA was then synthesized using the SMART cDNA Library Construction kit (Clontech, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. The PCR products of cDNA were purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) and checked for quality using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Approximately 10 ug cDNA from each of the two flower samples were used for sequencing on a GS-FLX platform. A half-plate sequencing run was performed for each sample at the Virginia Bioinformatics Institute Core Laboratory Facility following manufacturer's protocols. All the sequences can be downloaded and queried at the Cucubit Genomics Database [24].

cDNA sequence processing and assembly

The raw 454 sequence files in SFF format were base called using the Pyrobayes base caller [61]. In addition, around 7,000 EST and mRNA sequences were collected from GenBank in April, 2009. All these sequences were then processed to remove low quality regions and adaptor sequences using programs LUCY [62] and SeqClean [63]. The resulting high quality sequences were then screened against the NCBI UniVec database and E. coli genome sequences, as well as cucumber ribosomal RNA and chloroplast genome sequences, to remove possible contaminations. Sequences shorter than 30 bp were discarded. The processed 454 and GenBank sequences were assembled using the iAssembler program [64], which uses MIRA [65] and CAP3 [66] as the core assembly engines. The program performs post-assembly quality checking and automatically corrected mis-assemblies. The post-assembly quality checking mainly include 1) aligning each cDNA sequence to its corresponding unigene sequence to identify mis-assemblies; and 2) comparing unigene sequences against themselves to identify sequences from same genes that were not assembled together.

Mapping ESTs and unigenes to cucumber genome predicted genes and identification of alternatively spliced genes

Based on full length cDNA analysis in other plant species, the majority of plant genes have 5' and 3' UTRs less than 1,000 bp [67]. For each cucumber genome predicted gene, the gene region was defined as the region from up to 1,000 bp upstream of the translation start site to up to 1,000 bp downstream of the translation stop site, allowing no overlap with the neighboring genes. ESTs and unigenes were aligned to the gene regions using SPALN [68] for those longer than 100 bp and BLAT [69] for those shorter than 100 bp. Alternative splicing events and alternatively spliced genes were identified using a custom perl script based on the alignments of ESTs to the cucumber genome predicted genes.

Cucumber gene annotation and pathway prediction

Cucumber unigenes were blasted against GenBank non-redundant protein (nr) and UniProt databases with a cutoff e value of 1e-5. The unigene sequences were also translated into proteins using ESTScan [70] and the translated protein sequences were then compared to InterPro and pfam domain databases. The gene ontology (GO) terms were assigned to each unigene based on the GO terms annotated to its corresponding homologues in the UniProt database [71], as well as those to InterPro and pfam domains using interpro2go and pfam2go mapping files provided by the GO website [72], respectively. The GO annotations of cucumber unigenes were mapped to the plant-specific GO slim ontology using the map2slim script [36] and the unigenes were classified into different functional groups based on these GO slims. The annotations of cucumber unigenes were then formatted into the PathoLogic format and used to predict cucumber biochemical pathways using the Pathway Tools [37].

Identification of differentially expressed genes, SNPs and SSRs

Following cDNA sequence assembly and unigene mapping to cucumber genome predicted genes, transcript count information for sequences corresponding to each gene was associated with the corresponding tissue source to obtain relative expression levels following normalization to the total number of sequenced transcripts per sample. Significance of differential gene expression was determined using the R statistic described in Stekel et al. [73] and the resulting raw p values were converted to q values for multiple test corrections [74]. Genes with fold change greater than two and q value less than 0.05 were identified as differentially expressed genes. GO terms enriched in the set of differentially expressed genes were identified using GO::TermFinder [75], requiring p values adjusted for multiple testing to be less than 0.05.

SSRs were identified from the unigenes using the MISA program [76]. The minimum repeat number was six for dinucleotide and five for tri-, tetra-, penta- and hexa-nucleotide and the maximal distance interrupting two SSRs in a compound microsatellite was 100 bp. Primer pairs flanking each SSR loci were designed using the Primer3 program [77]. SNPs in the cDNA sequences between WI1983G and WI1983H were identified with PolyBayes [78]. To eliminate errors introduced by PCR amplification during the cDNA synthesis step and homopolymer errors introduced by the 454 pyrosequencing technology, and to distinguish true SNPs from allele differences, we further filtered the PolyBayes results and only kept SNPs meeting all the following criteria: 1) at least 2× coverage at the potential SNP site for each cultivar; 2) not an indel site surrounded by long stretch (> = 3) homopolyers; 3) no same bases at the potential SNP site between the two cultivars.

References

Tanurdzic M, Banks JA: Sex-determining mechanisms in land plants. Plant Cell. 2004, 16: S61-71. 10.1105/tpc.016667.

Kater MM, Franken J, Carney KJ, Colombo L, Angenent GC: Sex determination in the monoecious species cucumber is confined to specific floral whorls. Plant Cell. 2001, 13: 481-493. 10.1105/tpc.13.3.481.

Rudich J, Halevy AH, Kedar N: Ethylene evolution from cucumber plants as related to sex expression. Plant Physiol. 1972, 49: 998-999. 10.1104/pp.49.6.998.

Yin T, Quinn JA: Tests of a mechanistic model of one hormone regulating both sexes in Cucumis sativus (Cucurbitaceae). Am J Bot. 1995, 82: 1537-1546. 10.2307/2446182.

Pierce LK, Whener TC: Review of genes and linkage groups in cucumber. HortScience. 1990, 25: 605-615.

Boualem A, Fergany M, Fernandez R, Troadec C, Martin A, Morin H, Sari MA, Collin F, Flowers JM, Pitrat M, Purugganan MD, Dogimont C, Bendahmane A: A conserved mutation in an ethylene biosynthesis enzyme leads to andromonoecy in melons. Science. 2008, 321: 836-838. 10.1126/science.1159023.

Li Z, Huang S, Liu S, Pan J, Zhang Z, Tao Q, Shi Q, Jia Z, Zhang W, Chen H, Si L, Zhu L, Cai R: Molecular isolation of the M gene suggests that a conserved-residue conversion induces the formation of bisexual flowers in cucumber plants. Genetics. 2009, 182: 1381-1385. 10.1534/genetics.109.104737.

Trebitsh T, Staub JE, O'Neill SD: Identification of a 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase gene linked to the female (F) locus that enhances female sex expression in cucumber. Plant Physiol. 1997, 113: 987-995. 10.1104/pp.113.3.987.

Knopf RR, Trebitsh T: The female-speciWc Cs-ACS1G gene of cucumber. A case of gene duplication and recombination between the non-sex-speciWc 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase gene and a branched-chain amino acid transaminase gene. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006, 47: 1217-1228. 10.1093/pcp/pcj092.

Arumuganathan K, Earle E: Estimation of nuclear DNA content of plants by flow cytometry. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1991, 9: 208-218. 10.1007/BF02672069.

International Rice Genome Sequencing Project: The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature. 2005, 436: 793-800. 10.1038/nature03895.

Arabidopsis Genome Initiative: Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2000, 408: 796-815. 10.1038/35048692.

USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. [http://www.nass.usda.gov]

Huang S, Li R, Zhang Z, Li L, Gu X, Fan W, Lucas WJ, Wang X, Xie B, Ni P, Ren Y, Zhu H, Li J, Lin K, Jin W, Fei Z, Li G, Staub J, Kilian A, van der Vossen EA, Wu Y, Guo J, He J, Jia Z, Ren Y, Tian G, Lu Y, Ruan J, Qian W, Wang M, Huang Q, Li B, Xuan Z, Cao J, Asan , Wu Z, Zhang J, Cai Q, Bai Y, Zhao B, Han Y, Li Y, Li X, Wang S, Shi Q, Liu S, Cho WK, Kim JY, Xu Y, Heller-Uszynska K, Miao H, Cheng Z, Zhang S, Wu J, Yang Y, Kang H, Li M, Liang H, Ren X, Shi Z, Wen M, Jian M, Yang H, Zhang G, Yang Z, Chen R, Liu S, Li J, Ma L, Liu H, Zhou Y, Zhao J, Fang X, Li G, Fang L, Li Y, Liu D, Zheng H, Zhang Y, Qin N, Li Z, Yang G, Yang S, Bolund L, Kristiansen K, Zheng H, Li S, Zhang X, Yang H, Wang J, Sun R, Zhang B, Jiang S, Wang J, Du Y, Li S: The genome of the cucumber, Cucumis sativus L. Nat Genet. 2009, 41: 1275-1281. 10.1038/ng.475.

Bourdon V, Naef F, Rao PH, Reuter V, Mok SC, Bosl GJ, Koul S, Murty VV, Kucherlapati RS, Chaganti RS: Genomic and expression analysis of the 12p11-p12 amplicon using EST arrays identifies two novel amplified and overexpressed genes. Cancer Res. 2002, 62: 6218-6223.

Cheung F, Win J, Lang JM, Hamilton J, Vuong H, Leach JE, Kamoun S, Levesque AC, Tisserat N, Buell CR: Analysis of the Pythium ultimum transcriptome using Sanger and pyrosequencing approaches. BMC Genomics. 2008, 9: 542-10.1186/1471-2164-9-542.

Seki M, Narusaka M, Kamiya A, Ishida J, Satou M, Sakurai T, Nakajima M, Enju A, Akiyama K, Oono Y, Muramatsu M, Hayashizaki Y, Kawai J, Carninci P, Itoh M, Ishii Y, Arakawa T, Shibata K, Shinagawa A, Shinozaki K: Functional annotation of a full-length Arabidopsis cDNA collection. Science. 2002, 296: 141-145. 10.1126/science.1071006.

Nishiyama T, Fujita T, Shin-I T, Seki M, Nishide H, Uchiyama I, Kamiya A, Carninci P, Hayashizaki Y, Shinozaki K, Kohara Y, Hasebe M: Comparative genomics of Physcomitrella patens gametophytic transcriptome and Arabidopsis thaliana: Implication for land plant evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003, 100: 8007-8012. 10.1073/pnas.0932694100.

Ruyter-Spira CP, de Koning DJ, van der Poel JJ, Crooijmans RP, Dijkhof RJ, Groenen MA: Developing microsatellite markers from cDNA; A tool for adding expressed sequence tags to the genetic linkage map of the chicken. Anim Genet. 1998, 29: 85-90. 10.1046/j.1365-2052.1998.00304.x.

Gonzalo MJ, Oliver M, Garcia-Mas J, Monfort A, Dolcet-Sanjuan R, Katzir N, Arus P, Monforte AJ: Simple-sequence repeat markers used in merging linkage maps of melon (Cucumis melo L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2005, 110: 802-811. 10.1007/s00122-004-1814-6.

Fei Z, Tang X, Alba R, White J, Ronning C, Martin G, Tanksley S, Giovannoni J: Comprehensive EST analysis of tomato and comparative genomics of fruit ripening. Plant J. 2004, 40: 47-59. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02188.x.

Eveland AL, McCarty DR, Koch KE: Transcript profiling by 3'-untranslated region sequencing resolves expression of gene families. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146: 32-44. 10.1104/pp.107.108597.

NCBI-dbEST database. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/dbEST]

Cucurbit Genomics Database. [http://www.icugi.org]

Blencowe BJ: Alternative splicing: New insights from global analyses. Cell. 2006, 126: 37-47. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.023.

Macknight R, Duroux M, Laurie R, Dijkwel P, Simpson G, Dean C: Functional significance of the alternative transcript processing of the Arabidopsis floral promoter FCA. Plant Cell. 2002, 14: 877-888. 10.1105/tpc.010456.

Palusa SG, Ali GS, Reddy ASN: Alternative splicing of pre-mRNAs of Arabidopsis serine/arginine-rich proteins and its regulation by hormones and stresses. Plant J. 2007, 49: 1091-1107. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.03020.x.

Zhang XC, Gassmann W: Alternative splicing and mRNA levels of the disease resistance gene RPS4 are induced during defense responses. Plant Physiol. 2007, 145: 1577-1587. 10.1104/pp.107.108720.

Campbell MA, Haas BJ, Hamilton JP, Mount SM, Buell CR: Comprehensive analysis of alternative splicing in rice and comparative analyses with Arabidopsis. BMC Genomics. 2006, 7: 327-10.1186/1471-2164-7-327.

Wang BB, Brendel V: Genomewide comparative analysis of alternative splicing in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006, 103: 7175-7180. 10.1073/pnas.0602039103.

Ner-Gaon H, Halachmi R, Savaldi-Goldstein S, Rubin E, Ophir R, Fluhr R: Intron retention is a major phenomenon in alternative splicing in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2004, 39: 877-885. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02172.x.

Weber AP, Weber KL, Carr K, Wilkerson C, Ohlrogge JB: Sampling the Arabidopsis transcriptome with massively parallel pyrosequencing. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144: 32-42. 10.1104/pp.107.096677.

Mane SP, Evans C, Cooper KL, Crasta OR, Folkerts O, Hutchison SK, Harkins TT, Thierry-Mieg D, Thierry-Mieg J, Jensen RV: Transcriptome sequencing of the Microarray Quality Control (MAQC) RNA reference samples using next generation sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2009, 10: 264-10.1186/1471-2164-10-264.

Schmid M, Davison TS, Henz SR, Pape UJ, Demar M, Vingron M, Scholkopf B, Weigel D, Lohmann JU: A gene expression map of Arabidopsis thaliana development. Nat Genet. 2005, 37: 501-506. 10.1038/ng1543.

Ramskold D, Wang ET, Burge CB, Sandberg R: An abundance of ubuquitously expressed genes revealed by tissue transcriptome sequence data. PLoS Comp Biol. 2009, 5: e1000598-10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000598.

Plant specific GO slims. [http://www.geneontology.org/GO.slims.shtml]

Karp PD, Paley S, Romero P: The Pathway Tools software. Bioinformatics. 2002, 18: S225-S232.

Martin A, Troadec C, Boualem A, Rajab M, Fernandez R, Morin H, Pitrat M, Dogimont C, Bendahmane A: A transposon-induced epigenetic change leads to sex determination in melon. Nature. 2009, 461: 1135-1138. 10.1038/nature08498.

Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M: RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2009, 10: 57-63. 10.1038/nrg2484.

Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW: Gene expression analysis goes digital. Nat Biotechnol. 2007, 25: 878-880. 10.1038/nbt0807-878.

Ewing RM, Kahla AB, Poirot O, Lopez F, Audic S, Claverie JM: Large-scale statistical analyses of rice ESTs reveal correlated patterns of gene expression. Genome Res. 1999, 9: 950-959. 10.1101/gr.9.10.950.

Ogihara Y, Mochida K, Nemoto Y, Murai K, Yamazaki Y, Shin-I T, Kohara Y: Correlated clustering and virtual display of gene expression patterns in the wheat life cycle by large-scale statistical analyses of expressed sequence tags. Plant J. 2003, 33: 1001-1011. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01687.x.

Wang SM: Understanding SAGE data. Trends Genet. 2007, 23: 42-50. 10.1016/j.tig.2006.11.001.

Peng J, Richards DE, Hartley NM, Murphy GP, Devos KM, Flintham JE, Beales J, Fish LJ, Worland AJ, Pelica F, Sudhakar D, Christou P, Snape JW, Gale MD, Harberd NP: 'Green revolution' genes encode mutant gibberellin response modulators. Nature. 1999, 400: 256-261. 10.1038/22307.

Takahashi H, Jaffe MJ: Further studies of auxin and ACC induced feminization in the cucumber plant using ethylene inhibitors. Phyton (Buenos Aires). 1984, 44: 81-86.

Tiwari SB, Wang XJ, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ: AUX/IAA proteins are active repressors, and their stability and activity are modulated by auxin. Plant Cell. 2001, 13: 2809-2822. 10.1105/tpc.13.12.2809.

Papadopoulou E, Grumet R: Brassinosteriod-induced femaleness in cucumber and relationship to ethylene production. HortScience. 2005, 40: 1763-1767.

Li L, Deng XW: It runs in the family: regulation of brassinosteroid signaling by the BZR1-BES1 class of transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10: 266-268. 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.04.002.

Wang ZY, Nakano T, Gendron J, He J, Chen M, Vafeados D, Yang Y, Fujioka S, Yoshida S, Asami T, Chory J: Nuclear-localized BZR1 mediates brassinosteroid-induced growth and feedback suppression of brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Dev Cell. 2002, 2: 505-513. 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00153-3.

Li J, Chory J: A putative leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase involved in brassinosteroid signal transduction. Cell. 1997, 90: 929-938. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80357-8.

Li J, Wen J, Lease KA, Doke JT, Tax FE, Walker JC: BAK1, an Arabidopsis LRR receptor-like protein kinase, interacts with BRI1 and modulates brassinosteroid signaling. Cell. 2002, 110: 213-222. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00812-7.

Nam KH, Li J: BRI1/BAK1, a receptor kinase pair mediating brassinosteroid signaling. Cell. 2002, 110: 203-212. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00814-0.

Caudy M, Vässin H, Brand M, Tuma R, Jan LY, Jan YN: daughterless, a Drosophila gene essential for both neurogenesis and sex determination, has sequence similarities to myc and the achaete-scute complex. Cell. 1988, 55: 1061-1067. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90250-4.

Heslop-Harrison J: The experimental modification of sex expression in flowering plants. Biol Rev. 1957, 32: 38-90. 10.1111/j.1469-185X.1957.tb01576.x.

Korpelainen H: Labile sex expression in plants. Biol Rev. 1998, 73: 157-180. 10.1017/S0006323197005148.

Thiel T, Michalek W, Varshney RK, Graner A: Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene-derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2003, 106: 411-422.

Levi A, Wechter P, Davis A: EST-PCR markers representing watermelon fruit genes are polymorphic among watermelon heirloom cultivars sharing a narrow genetic base. Plant Genetic Resources. 2009, 7: 16-32. 10.1017/S1479262108014366.

Peterson CE, Staub JE, Williams PH, Palmer MJ: Wisconsin 1983 Cucumber. HortScience. 1986, 21: 1082-1083.

Liu S, Xu L, Jia Z, Xu Y, Yang Q, Fei Z, Lu X, Chen H, Huang S: Genetic association of ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3-like sequence with the sex-determining M locus in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2008, 117: 927-933. 10.1007/s00122-008-0832-1.

Bai SL, Peng YB, Cui JX, Gu HT, Xu LY, Li YQ, Xu ZH, Bai SN: Developmental analyses reveal early arrests of the spore-bearing parts of reproductive organs in unisexual flowers of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Planta. 2004, 220: 230-240. 10.1007/s00425-004-1342-2.

Quinlan AR, Stewart DA, Strömberg MP, Marth GT: Pyrobayes: an improved base caller for SNP discovery in pyrosequences. Nat Methods. 2008, 5: 179-181. 10.1038/nmeth.1172.

Chou HH, Holmes MH: DNA sequence quality trimming and vector removal. Bioinformatics. 2001, 17: 1093-1104. 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1093.

SeqClean program. [http://compbio.dfci.harvard.edu/tgi/software]

iAssembler program. [http://bioinfo.bti.cornell.edu/tool/iAssembler]

Chevreux B, Pfisterer T, Drescher B, Driesel AJ, Müller WE, Wetter T, Suhai S: Using the miraEST assembler for reliable and automated mRNA transcript assembly and SNP detection in sequenced ESTs. Genome Res. 2004, 14: 1147-1159. 10.1101/gr.1917404.

Huang X, Madan A: CAP3: A DNA sequence assembly program. Genome Res. 1999, 9: 868-877. 10.1101/gr.9.9.868.

Aoki K, Yano K, Suzuki A, Kawamura S, Sakurai N, Suda K, Kurabayashi A, Suzuki T, Tsugane T, Watanabe M, Ooga K, Torii M, Narita T, Shin-I T, Kohara Y, Yamamoto N, Takahashi H, Watanabe Y, Egusa M, Kodama M, Ichinose Y, Kikuchi M, Fukushima S, Okabe A, Arie T, Sato Y, Yazawa K, Satoh S, Omura T, Ezura H, Shibata D: Large-scale analysis of full-length cDNAs from the tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) cultivar Micro-Tom, a reference system for the Solanaceae genomics. BMC Genomics. 2010, 11: 210-10.1186/1471-2164-11-210.

Gotoh O: A space-efficient and accurate method for mapping and aligning cDNA sequences onto genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36: 2630-2638. 10.1093/nar/gkn105.

Kent WJ: BLAT--the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002, 12: 656-664.

Iseli C, Jongeneel CV, Bucher P: ESTScan: a program for detecting, evaluating, and reconstructing potential coding regions in EST sequences. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1999, 138-148.

Camon E, Magrane M, Barrell D, Lee V, Dimmer E, Maslen J, Binns D, Harte N, Lopez R, Apweiler R: The Gene Ontology Annotation (GOA) Database: sharing knowledge in Uniprot with Gene Ontology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32: D262-266. 10.1093/nar/gkh021.

Gene Ontology Database. [http://www.geneontology.org]

Stekel DJ, Git Y, Falciani F: The comparison of gene expression from multiple cDNA libraries. Genome Res. 2000, 10: 2055-2061. 10.1101/gr.GR-1325RR.

Storey JD: The positive false discovery rate: A Bayesian interpretation and the q-value. Annals of Statistics. 2003, 31: 2013-2035. 10.1214/aos/1074290335.

Boyle EI, Weng S, Gollub J, Jin H, Botstein D, Cherry JM, Sherlock G: GO:TermFinder: open source software for accessing Gene Ontology information and finding significantly enriched Gene Ontology terms associated with a list of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004, 20: 3710-3715. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth456.

MISA program. [http://pgrc.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa]

Primer3 program. [http://frodo.wi.mit.edu]

Marth GT, Korf I, Yandell MD, Yeh RT, Gu Z, Zakeri H, Stitziel NO, Hillier L, Kwok PY, Gish WR: A general approach to single-nucleotide polymorphism discovery. Nat Genet. 1999, 23: 452-456. 10.1038/70570.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Ms. Mingyun Huang for her help in setting up the cucumber pathway database and genome browser. This work was supported by United States Department of Agriculture - Agricultural Research Service, the National Science Foundation (IOS-0501778 and IOS-0923312 to ZF), the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture (the 948 program: 2008-Z42 to SH), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (30871707 to SH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Authors' contributions

SG and YZ performed the sequence analysis. JG performed the alternative splicing analysis. SL prepared cDNA samples for 454 sequencing. ZZ and YX helped with data interpretation. ORC and BWS helped with the 454 sequencing. ZF and SH designed the experiment and provided guidance on the whole study. ZF was also involved in sequence analysis and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Shaogui Guo, Yi Zheng contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

12864_2010_2978_MOESM1_ESM.XLS

Additional file 1: List of alternatively spliced genes. The table provides the list of alternative splicing events and alternatively spliced genes identified from cucumber ESTs. (XLS 640 KB)

12864_2010_2978_MOESM2_ESM.XLS

Additional file 2: List of differentially expressed genes. The table provides the list of genes differentially expressed in flowers of gynoecious (WI1983G) and hermaphroditic (WI1983H) plants. (XLS 68 KB)

12864_2010_2978_MOESM3_ESM.XLS

Additional file 3: Cucumber SSRs. The table provides the list of SSRs identified from cucumber ESTs, their motif sequences and surrounding primer pair information. (XLS 1 MB)

12864_2010_2978_MOESM4_ESM.XLS

Additional file 4: Cucumber SNPs. The table provides the list of SNPs identified from the cucumber EST collection. (XLS 64 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, S., Zheng, Y., Joung, JG. et al. Transcriptome sequencing and comparative analysis of cucumber flowers with different sex types. BMC Genomics 11, 384 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-11-384

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-11-384