Abstract

Background

SnoRNAs represent an excellent model for studying the structural and functional evolution of small non-coding RNAs involved in the post-transcriptional modification machinery for rRNAs and snRNAs in eukaryotic cells. Identification of snoRNAs from Neurospora crassa, an important model organism playing key roles in the development of modern genetics, biochemistry and molecular biology will provide insights into the evolution of snoRNA genes in the fungus kingdom.

Results

Fifty five box C/D snoRNAs were identified and predicted to guide 71 2'-O-methylated sites including four sites on snRNAs and three sites on tRNAs. Additionally, twenty box H/ACA snoRNAs, which potentially guide 17 pseudouridylations on rRNAs, were also identified. Although not exhaustive, the study provides the first comprehensive list of two major families of snoRNAs from the filamentous fungus N. crassa. The independently transcribed strategy dominates in the expression of box H/ACA snoRNA genes, whereas most of the box C/D snoRNA genes are intron-encoded. This shows that different genomic organizations and expression modes have been adopted by the two major classes of snoRNA genes in N. crassa . Remarkably, five gene clusters represent an outstanding organization of box C/D snoRNA genes, which are well conserved among yeasts and multicellular fungi, implying their functional importance for the fungus cells. Interestingly, alternative splicing events were found in the expression of two polycistronic snoRNA gene hosts that resemble the UHG-like genes in mammals. Phylogenetic analysis further revealed that the extensive separation and recombination of two functional elements of snoRNA genes has occurred during fungus evolution.

Conclusion

This is the first genome-wide analysis of the filamentous fungus N. crassa snoRNAs that aids in understanding the differences between unicellular fungi and multicellular fungi. As compared with two yeasts, a more complex pattern of methylation guided by box C/D snoRNAs in multicellular fungus than in unicellular yeasts was revealed, indicating the high diversity of post-transcriptional modification guided by snoRNAs in the fungus kingdom.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Eukaryotic rRNAs contain a large number of nucleotide modifications including 2'-O-methylation and pseudouridylation which are directed by box C/D snoRNAs and box H/ACA snoRNAs, respectively [1, 2]. These modifications are usually found in the conserved core regions of rRNAs, and they play important roles in ribosome function [3]. SnoRNAs are among the most numerous and functionally diverse non-coding RNAs currently known [4, 5], existing widely in eukaryotes including human [6–8], plants [9–11], yeasts [12–15] and protists [16–19], as well as in Archaea [20]. This indicates that they are ancient molecules that arose over 2-3 billion years ago [21]. In addition to guiding the posttranscriptional modifications of rRNAs in eukaryotes and Archaea, snoRNAs also interact with spliceosomal RNAs [22], tRNAs [23, 24], SL RNAs in trypanosomes [25], and at least one brain-specific mRNA in mammals [26]. Recently, snoRNA U50 was found to be a candidate tumor suppressor gene in prostate cancer [27]. The existence of substantial numbers of orphan snoRNAs indicates that snoRNAs also participate in diverse biological processes that remain to be identified [4].

SnoRNAs exhibit canonical sequence motifs and structural features. Box C/D snoRNAs carry the conserved box C (RUGAUGA, where R can be any purine) and D (CUGA) motifs near their 5' and 3' termini, respectively. Additionally, the variants of the C and D boxes, designated C' and D' box, are usually present internally [28]. Box H/ACA snoRNAs possess a hairpin-hinge-hairpin-tail secondary structure and two conserved sequence motifs, box H and box ACA. The hinge region contains the H box (ANANNA) and the tail consists of the ACA box located 3 nt before the 3' end [29, 30]. The snoRNAs exert their functions by base-pairing with their targets and recruit related proteins to the sites of modification [31]. Box C/D snoRNAs can form 10-21 basepairs (bp) with multiple cellular RNAs. The methylated nucleotide in the target RNA is usually positioned 5 nt upstream of the D or D' box of the snoRNAs, the so called "D/D'+5" rule [6]. In box H/ACA snoRNAs, two short antisense sequences in one or both of the two hairpin domains form 9-13 basepairs with rRNA sequences that flank the target uridine to be converted to pseudouridine. The pseudouridine is always located 14 to 16 nt upstream from the H box or the ACA box of the snoRNA [29, 30]. These structural and functional features of box C/D and H/ACA snoRNAs provide the parameters for identifying snoRNAs and their function.

The genomic organization of snoRNA genes displays great diversity in different organisms. In vertebrates, almost all snoRNA genes are located in the introns of host genes, with a few exceptions, such as U3 which are independently transcribed [4]. In plants and trypanosomatids, snoRNA genes are present in polycistronic clusters which encode both C/D and H/ACA snoRNAs [9, 17]. A particular genomic organization, the intronic gene cluster, was first found in rice and then in Drosophila melanogaster [32, 33]. Moreover, a unique genomic organization (dicistronic tRNA-snoRNA genes) has been characterized exclusively in plants [34]. The genomic organization of snoRNA genes differs largely in fungi. In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, apart from seven intronic snoRNA genes, the majority of snoRNA are encoded by independent genes as well as five polycistronic snoRNA gene clusters [12]. In contrast, most box C/D snoRNA genes from the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe are intron-encoded. This raises the question about the genomic organization and expression modes of snoRNA genes in the fungus kingdom. It is well known that multicellular fungi dominate the population of fungi. However, little is known about snoRNAs in multicellular fungi. It was thus of interest to determine the snoRNA genes from a multicellular fungi to shed light on these characteristics.

Neurospora crassa is a filamentous fungus sharing key components with animal cells in cellular physiology and genetics, contributing to the fundamental understanding of the genome defense system, DNA methylation, post-transcriptional gene silencing, cellular differentiation and development [35]. As a model eukaryote, the genome of N. crassa has been completely sequenced [36]. However, only four box C/D snoRNAs, snR39, snR52, snR60, snR61 (Rfam) were annotated in N. crassa . Recently, we identified three U3 snoRNA genes from N. crassa; each of them is independently transcribed and contains a small intron [37](Table 1). It is evident that the majority of the N. crassa snoRNAs remain to be identified. Meanwhile, a comparative genome analysis between yeast and multicellular fungi will provide insights into the evolution of snoRNA genes in the fungus kingdom. In this study, by combining computational and experimental methods, an extensive analysis of snoRNA genes from N. crassa was performed. Here, we present the first comprehensive list of two major families of snoRNAs from N. crassa , and further discuss the characteristics and evolutionary significance of the snoRNA genes.

Results

Identification of 55 box C/D and 20 box H/ACA snoRNAs from N. crassa

We initially carried out the genome-wide analysis of snoRNAs from N. crassa by employing the snoscan [12] and snoGPS programs [13]. From this database search, 89 box C/D and 131 box H/ACA snoRNA candidates were predicted (see Methods). To validate the snoRNA candidates and identify more novel snoRNAs from N. crassa , the box C/D and box H/ACA snoRNA-specific library of N. crassa were respectively constructed from mixed-stage mycelium and spores using anchored primers (18, and see Methods). To exclude the highly abundant clones and enrich the novel RNA species in our analysis, the radiolabelled oligonucleotides were used to screen the cDNA libraries (~1800 clones in the box C/D and ~ 4000 clones in box H/ACA snoRNA libraries). Subsequently, a total of 338 and 278 clones from box C/D and box H/ACA snoRNA libraries were sequenced, respectively. Taken together, 65 snoRNAs including 45 box C/D (Table 1) and 20 box H/ACA snoRNAs (Table 2) were identified. Twenty eight box C/D snoRNAs from the cDNA library were covered by the snoscan results. However, only three H/ACA snoRNAs overlapped with snoGPS results. Because the data from the computational search of H/ACA snoRNAs may include excessive false-positive candidates, they were not included for further analyses in this study.

The snoRNA candidates identified by cDNA cloning or the snoscan program were subsequently confirmed by northern blot and/or reverse transcription analyses. The expression of 27 box C/D and all 20 box H/ACA snoRNAs were positively detected as expected (Figure 1 and 2). Among these snoRNAs, the sequence of CD31 snoRNA obtained from the cDNA cloning appears uncompleted; it corresponds to the second half of CD31 full-length which is further validated by the northern blotting.

Northern blot and RT analyses of box C/D snoRNAs from N. crassa. A. Northern blot analyses of box C/D snoRNAs. B. Reverse transcription analyses of box C/D snoRNAs generated from the computational screen. Lane M, molecular weight marker (pBR322 digested with Hae III and 5'-end -labeled with [γ-32P]ATP).

Northern blot and RT analyses of box H/ACA snoRNAs from N. crassa. A. Northern blot analyses of box H/ACA snoRNAs. B. Reverse transcription analyses of the three box H/ACA snoRNAs overlaps with the computational screen. Lane M, molecular weight marker (pBR322 digested with Hae III and 5'-end -labeled with [γ-32P]ATP.

Together, through the combination of computational analysis and construction of the specialized cDNA libraries, 55 box C/D and 20 box H/ACA snoRNAs were identified and all the snoRNAs are denominated according to the order of identification (Table 1 and 2).

In most cases (86%) the C and D boxes in snoRNAs are highly conserved when compared to the consensus sequence (UGAUGA and CUGA, see Additional file 1). However, the C' and D' box are nonconserved and exhibit much more sequence-degeneracy than their C and D box counterparts. In some instances, the C' and D' box cannot be unambiguously inferred as a result of the absence of the functional region. Generally, the box C/D snoRNAs from N. crassa are similar to their metazoan and yeast counterparts in size. However, the sizes of box H/ACA snoRNAs from N. crassa are peculiar. Almost all of them are larger than 160 nt (Figure 2), reminiscent of some irregular box H/ACA snoRNAs in S. cerevisiae. These observations show that the N. crassa snoRNAs have their own unique sequence and structural features (see Additional file 2 and 3).

Functional properties of the N. crassa box C/D and box H/ACA snoRNAs

Based on the modification rules of snoRNAs [2] , 55 box C/D snoRNAs from N. crassa were predicted to direct 71 methylations. These include 64 methylations on rRNAs which comprise 43 methyls on 26S rRNA, 20 methyls on 18S rRNA and one methyl on 5.8S rRNA (see Additional file 4A). The remnant seven methylations consist of four methyls on snRNAs and three methyls on tRNAs (see Additional file 4B and 4C). Furthermore, the structure and function elements of U14 which participate in the processing of pre-rRNA were unambiguously identified. Interestingly, two different methylated sites were predicted to be guided by the same functional element of a single snoRNA CD27. Two box C/D snoRNAs (CD53 and CD55) lack the sequences complementary to either rRNAs or snRNAs and therefore belong to orphan snoRNAs. Fourteen box H/ACA snoRNAs were predicted to guide 17 pseudouridine sites of rRNAs (see Additional file 5), and no pseudouridine sites on snRNAs were predicted. The remaining six box H/ACA snoRNAs were also classified into an orphan snoRNA family lacking functional region complementary to rRNA, tRNA or snRNA. A different modification pattern appears in N. crassa as compared to the two yeasts S. cerevisiae, and S. pombe (see discussion)[38, 39].

Interestingly, a novel snoRNA, CD29, possesses two guide elements that can form duplexes with U2 snRNA and 5.8S rRNA for 2'-O-methylation. Primer extension mapping of 2'-O-methylated nucleotides of the U2 snRNA and 5.8S rRNA in the presence of low concentration of dNTPs resulted in stop signals at the G32 and A43 residues, indicating that U2-A31 and 5.8S-A42 are methylated (Figure 3). We have identified cognates of CD29 in other filamentous fungi, however, these cognates only possess the guide sequence for the methylation of U2 snRNA. This suggests that CD29 evolves from the snoRNA with a single guide function. This is reminiscent of the human small Cajal body-specific RNAs (scaRNAs) that can guide modification of the RNA polymerase II-transcribed snRNAs such as U2 snRNA. The comparative analyses revealed that CD29 and its homologs in fungi have one functional element similar to that of human SCARNA9 which was first known as Z32 (GeneBank accession no. AJ009638), and therefore was homologous to this human scaRNA. In addition, we characterized a multi-function box C/D snoRNA, CD11, in N. crassa . CD11 has the potential to direct a methylation in U6 snRNA, and two methylations in 18S and 26S rRNAs, respectively (Figure 3). Interestingly, the CD11 is also partially similar to mgU6-47 in mammals [40], but possesses a novel function that can guide a N. crassa-specific methylation on 26S rRNA at A356.

Base-pairing model and verification of modification guided by CD11 (A) and CD29 (B). Black dots indicate nucleotides predicted to be methylated. Lane H, control reaction at 1.0 mM dNTP; Lane L, primer extension at 0.004 mM dNTP, and A, C, G and T lanes, the rDNA sequence ladder. Black triangles indicate potential methylation sites.

Genomic organization and expression of the snoRNAs in N. crassa

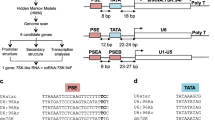

The genomic organization of the snoRNA genes in N. crassa exhibits great diversity. Among the 55 box C/D snoRNAs, forty five snoRNA genes are intron-encoded in protein-coding or non-coding host genes. The remaining nine were found in the intergenic regions with a putative polymerase II promoter upstream and appeared independently transcribed. Meanwhile, six gene clusters that only encode box C/D snoRNAs were identified from N. crassa . Interestingly, an exon-encoded snoRNA (CD6) was identified in the snoRNA gene cluster III in contrast to another two intron-encoded snoRNAs (CD9 and CD17) in the same cluster (Figure 5). Of 20 box H/ACA snoRNA genes, 16 are located in intergenic regions and two are intron-encoded. In particular, two snoRNA genes (ACA10 and ACA16) are located in the 3' UTR of two hypothetical protein genes, one of which is similar to phosphoglycerate mutase. Obviously, different strategies dominate in the expression of the two families of snoRNA genes in N. crassa .

In accordance with the mode of one snoRNA per intron in vertebrates [4], a large proportion of the box C/D snoRNA genes (45 of 55) are located within introns of the host genes. The distances from the intronic snoRNA genes to the 3' splice sites of introns, which has been proven to be important for the effective processing of intronic snoRNAs from their host mRNA precursors [41, 42], resemble those in D. melanogaster [32, 41, 42]. The distances from the snoRNA genes to the 5' splice sites appear to mainly be between 41 to 60 nt, similar to those in human[41] (Figure 4).

Remarkably, five (cluster I to V) of the six box C/D snoRNA gene clusters arehighly conserved between yeast and N. crassa (Figure 5). Although these host genes were not well annotated for their introns and exons in the N. crassa genome, canonical intron splicing sequences were observed flanking every cluster of snoRNA genes. To further confirm this observation, the mature RNA transcripts were identified with the expected sizes by cloning and sequencing of RT-PCR products. It is worth noting that two snoRNA genes, CD16 and CD37, in the cluster V are validated to be co-transcribed by RT-PCR and sequencing, though each of the snoRNA genes in the cluster has a putative promoter upstream. Intriguingly, the putative promoter upstream of CD37, a homologue of U14, would play a role in guaranteeing and promoting the function of U14 that has been demonstrated vital in diverse eukaryotes. Our results further revealed that the genomic organization of the host genes for these five clusters is most like the UHG gene in animals. The host genes of Cluster I to V only contain short open reading frames with length ranging from 159 bp to 267 bp, suggesting the little potential for protein coding just like the gas 5 [43].

Unexpectedly, various alternative splicing events were found in the processing of polycistronic transcripts from the snoRNA gene clusters I and II by analyzing cDNA sequences from RT-PCR of the transcripts (Figure 6). In cluster I, two alternatively spliced transcripts, differing by the absence of exon 2 or exon 2 plus exon 3 were detected. The pattern of alternative splicing in the expression of cluster II was contingent on an alternative 3' splice site that allows the lengthening or shortening of exon 3.

Alternative splicing in the expression of snoRNA gene cluster I and II in N. crassa. The open and black boxes represent snoRNAs and exons, respectively. The number below indicates the length (in nucleotides) of exons and introns. Thinner lines indicate introns and dashed lines indicate splicing activities. Arrows indicate the primers used in RT-PCR analysis.

Discussion

High diversity of post-transcriptional modification predicted by snoRNAs in fungi

Identification of guide snoRNAs in diverse organisms can provide valuable information towards understanding RNA modification patterns and their function [18]. It is interesting to compare the pattern of modifications on target RNAs of N. crassa to those described in the two yeasts, S. cerevisiae and S. pombe. Among 71 methylations predicted by the guide snoRNAs in N. crassa , 32 represent the most highly conserved modifications shared by the multicellular fungi and the yeasts, and 31 (43.7%) are modifications that have not yet been reported in other fungi when compared with the two unicellular yeasts(Figure 7). In the yeasts, only ten and eight methylations are S. cerevisiae-specific and S. pombe-specific, respectively. Our results imply a more complex modification pattern in multicellular fungi than in unicellular yeasts. They also reveal the high diversity of post-transcriptional modification of RNAs in the fungus kingdom as it has been shown that about 40% of methylations are species-specific in a protozoan Trypanosoma [17]. The species-specific modifications highlight the different modification patterns and their peculiar importance. Although eliminating a single modification does not have a dramatic effect on the ribosome [44], loss of three to five modifications in an intersubunit bridge of the ribosome (helix 69) impairs growth and causes broad defects in ribosome biogenesis and activity [45]. On the other hand, early studies have demonstrated that ribosome modifications play roles in determining antibiotic resistance or sensitivity [15, 46]. Thus the species-specific modifications have potential use in finding therapeutic targets for prevention and treatment of diseases caused by some eukaryotic pathogens.

Another interesting observation in this study was the presence of duplexes between box C/D snoRNAs and tRNAs (tRNATrp and tRNALeu from N. crassa Database). Duplexes between tRNA and snoRNAs have been also found in C. elegans [24] and recently in Plasmodium falciparum [47]. tRNA modification guided by snoRNAs has been also reported in Archaea [23]. This study provides for the first time a prediction of fungal snoRNAs and their potential target sites in tRNAs, although these remain to be confirmed by further experiments.

Structural and functional evolution of snoRNAs in fungi

Our study demonstrates the extensive separation and recombination of functional regions occurring during the evolution of snoRNA genes in fungi. For instance, the CD5 snoRNA in N. crassa possesses two conserved guiding elements. In S. cerevisiae, however, the conserved function of CD5 is executed by two independent snoRNAs, snR72 and snR78, with a single functional element [48] (Figure 8). This suggests that CD5 may have evolved as a double-guide snoRNA through recombination of two different halves of two ancestral single-guide snoRNAs. The other possibility is that a gene duplication of a double-guide snoRNA gene in S. cerevisiae led to specialization of each paralog to only target one modification site followed by loss of the other guide element for both paralogs. Another example is CD50 and CD51 that carry a conserved guiding function for U24 and U24b in S. pombe, respectively. In contrast, the U24 in S. cerevisiae has two guiding functions. Comparative analyses revealed that the structure and function of U24 are well conserved among the budding yeast and the flowering plants A. thaliana and rice, but the homologues of the S. cerevisiae U24 exist as two independent snoRNAs in other distant eukaryotes, such as human and mouse [49]. This suggests that U24 snoRNA gene has evolved in two pathways, with one leading to a dual functional snoRNA gene and the other separating the guiding functions and giving rise to two independent snoRNA genes.

It has been demonstrated the reciprocal evolutionary change between snoRNA complementary region and their rRNA target sequence in plants and nematodes[9, 24]. Our analyses indicate that co-evolution between snoRNAs and rRNAs exists widely in N. crassa (Figure 9) and plays an important role in preservation of phylogenetic conserved methylated sites of rRNAs which is essential for protein synthesis.

Coevolution between snoRNAs and their targets. A. Nucleotides of box C/D snoRNAs in the complementary region were changed in coordination with its target rRNA maintaining phylogenetical conservation of rRNA methylated sites. B. Nucleotides changed in box H/ACA snoRNAs respond to specific changes in the 18S rRNA of N. crassa . The nucleotides marked by black dot represent the 2'-O-methylation. Basepairs changed are indicated by arrows.

RIP may impact on the generation of snoRNA isoforms by gene duplication and transposition

SnoRNA gene isoforms or variants exist widely in diverse organisms, particularly in plants. For example, 97 box C/D snoRNAs with a total of 175 different gene variants were identified in the A. thaliana genome [50], and 346 gene variants encoding 120 box C/D snoRNAs were found in Oryza Sativa [9]. Compared with the plant snoRNAs, only a paucity of yeast snoRNA paralogs was detected because of a relatively small compact genome (~12 Mb for S. cerevisiae). The N. crassa genome (~ 40 Mb) is three-fold larger than that of the yeast; however, most snoRNA genes in this species are singleton. Why are the snoRNA genes devoid of isoforms in the N. crassa genome? It is known that a mutagenic process termed repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) has a profound impact on N. crassa genome evolution, which has greatly slowed the creation of new genes through genomic duplication and resulted in a genome with an unusually low proportion of closely related genes [51]. Of the predicted 10082 protein-coding genes, only six pairs (12 genes) share >80% nucleotide or amino-acid identities in their coding sequences [36]. RIP identifies duplications that are greater than ~400 bp (~1 kb in the case of unlinked duplications) and induces C:G to T:A during the sexual cycle [52, 53]. Early studies have provided clear evidence of retrotransposons inactivated by RIP [54, 55]. The analysis of the N. crassa genome sequence also revealed a complete absence of intact mobile elements [36]. Therefore the creation of new genes including snoRNA genes or their host genes through gene duplication and transposition seems to be impeded. It has been proposed that most, if not all paralogs in N. crassa duplicated and diverged before the emergence of RIP [51]. We have identified three U3 snoRNA gene variants, NcU3A, NcU3A-2 and NcU3A-3 in N. crassa (37). The sequence analysis revealed that these molecules have undergone nucleotide substitutions rather than RIP according to the calculation method previously reported [36]. In the case of CD46A and CD46B, we speculate that the two snoRNA gene isoforms may have duplicated and diverged before the emergence of RIP.

Alternative splicing in the expression of non-coding RNA genes with introns

It is well known that alternative splicing is an important and widespread process where one gene produces more than one type of mRNA which is then translated into different proteins in multicellular organisms [56]. Bioinformatic analysis indicates that 35-65% of human genes are involved in alternative splicing, which contributes significantly to human proteome complexity [57, 58]. However, alternative splicing is rarely reported for non-coding RNA genes which encode multiple introns. In this study, we identified several alternative splicing events that occurred in the processing of RNA precursors transcribed from the snoRNA gene cluster I and II of N. crassa. It has been reported that the mouse gas5 gene, a non-coding RNA and snoRNA host gene, had four alternative splicing transcripts [43]. Although different in snoRNA composition, the snoRNA gene clusters in N. crassa are most like UHG genes resembling gas5. Our results show that alternative splicing occurs frequently in the expression of snoRNA host genes in lower eukaryotes. This lends support to the concept that alternative splicing may be an ancient mechanism in regulating the expression of both protein-coding and non-coding RNA genes with introns. More work is necessary to elucidate the biological significance of the alternative splicing in the expression of non-coding RNA genes.

Conclusion

In this study, we report the first extensive identification of box C/D and box H/ACA snoRNAs from the filamentous fungus N. crassa using a combination of computational and experimental method. The repertoire characteristics, targets, genomic organization and the unique function of the N. crassa snoRNA genes were extensively compared with those of potential orthologues in close and distant organisms such as S. pombe, S. cerevisiae, A. n iger, M. grisea, A. thaliana and H. sapiens . Our results improve annotation of snoRNA genes in the N. crassa genome, an important model filamentous fungus, and provide insights into the characteristics and evolutionary significance of the snoRNA genes in the fungus kingdom.

Methods

Strains and Media

The N. crassa wild-type strain (As 3.1604, purchased from the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center) was used for the construction of the cDNA library and all RNA analyses. The strain was grown in PSA medium (2% sucrose, 20% extract of potato) at 30°C. The Escherichia coli strain TG1 grown in 2YT (1.6% Bacto tryptone, 1% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl) liquid or solid medium was used for cloning procedures.

Construction and screening of cDNA library

We prepared total RNA from N. crassa culture according to the guanidine thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform procedure described by Chomoczynski et al [59]. Small RNA (~20 μg) was fractionated by 50% PEG-8000 and 0.5 M NaCl. The construction of cDNA library were performed as described previously with minor modifications (see Additional file 6) [60]. After randomly sequencing clones, we employed dot hybridization to screen the colony PCR products with P47 and P48 as described by Liu et al. [37] We sequenced clones exhibiting the lowest hybridization signal.

Computational identification of box C/D snoRNA genes

Genomic sequences of N. crassa [36] available at http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/genome/neurospora/Home.html (N. crassa assembly 7) were downloaded and searched for potential box C/D snoRNAs target rRNA/snRNA using snoscan [12] with default parameters. Methylated sites prepared for the snoscan included the conserved methylated nucleotides of S. cerevisiae (yeast snoRNA database), H. sapiens (snoRNA-LBME-db), and D. melanogaster [32]. The snoscan results were processed by an in-house developed perl program for candidate selection. A sequence with the following characteristics was considered as candidate: ① box C motif bit score ≥ 7.48, box D motif bit score ≥ 8.05, ② the guide bit score ≥ 18.65, the guide sequence and the target sequence can form a concatenated 10 bp duplex with at most 1 GU pair allowed, or can form a concatenated 9 bp duplex with high GC content. ③ if the guide region is adjacent to the D' box, the length of spaces between box C and guide sequence must be ≤ 20 bp. If the guide region is adjacent to the D box, the length of spaces between box C and guide sequence must be between 40 and 85 bp. ④ total sequence length between 75 bp and 130 bp, total overall bit score ≥ 20. The candidates within CDS region predicted by Broad/Whitehead Institute automatic gene calling software (a combination of manual annotation, FGENESH, GENEID, and GENEWISE) [36] were removed. The BLAST program [61] was used to search gene variants of all novel snoRNA genes to establish the snoRNA gene isoforms. About 1 kb of flanking sequences of the snoRNA gene candidates was searched further for possible box C/D snoRNA genes and additional non-canonical C/D gene candidates.

Northern blot analysis

An aliquot of 30 μg total RNA was separated by electrophoresis on an 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 8 M urea and electrotransferred onto nylon membrane (Hybond-N+; Amersham) using semi-dry blotting apparatus (BioRad). After immobilizing RNA using a UV cross-linker, northern blot hybridization was performed as previously described [49].

Reverse transcription and mapping of ribose methylation

Reverse transcription was carried out in a 20 μl reaction mixture containing 15 μg of total RNA and a corresponding 5'-end-labeled primer. After denaturation at 65°C for 5 min and then cooling to 42°C, 200 units of M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega) were added and extension carried out at 42°C for 1 hour. The cDNA was separated on an 8% polyacrylamide gel (8 M urea) and then analyzed with an imager.

The mapping of rRNA methylated sites was determined by primer extension at low dNTP concentrations as described previously [40, 62]. Briefly, the N. crassa 18S and 26S rDNA were amplified by PCR with the primer pair Nc18SF/Nc18SR and Nc26SF/Nc26SR, respectively, and then cloned into the pMD-18T vector (Takara). The plasmid DNA insert was directly sequenced with the same primer used for reverse transcription and run in parallel with the reverse transcription reaction on an 8% polyacrylamide gel (8 M urea).

RT-PCR analysis

15 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed with 200 U of M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega) using the box C/D snoRNA gene cluster specific reverse primers (see Additional file 7) in a 20 μl reaction mixture as described above for reverse transcription and mapping of ribose methylations. The negative RT control was carried out without M-MLV reverse transcriptase. We designed two specific antisense oligonucleotides: the first reverse primer used in the reverse transcription reaction overlaps the last several nucleotides of the second reverse primer used in the PCR reaction to help avoid non-specific PCR products. After 1 h at 42°C, 2 μl of RT reaction was used for PCR amplification with the second reverse primer and the corresponding forward primer (see Additional file 7) in a final volume of 20 μl. The positive PCR control was performed on N. crassa genomic DNA with the same pair of primers. Negative PCR control was performed on 2 μl of the negative control RT reaction with the same pair of primers. The PCR program: 30 cycles of denaturation (30 s, 94°C), annealing (30 s, 50-55°C), and extension (1-2 min, 72°C), following by a final extension (10 min, 72°C). The PCR product was purified from a 1.5% agarose gel with the QIAquick Gel extraction Kit (QIAGEN) and cloned into pMD-18T vector (Takara) and transformed into the strain TG1 of E. coli . Positive clones were subsequently chosen for sequencing.

Oligonucleotides

Oligonucleotides used for construction of the cDNA library, northern blot analyses of novel snoRNAs and the primers for reverse transcription and RT-PCR experiments are not shown (see Additional file 7).

Database accession numbers

The sequences of all snoRNAs determined in this work have been deposited in the GenBank Nucleotide Sequence Databases under accession numbers EU780925 - EU780999 and EU526091-EU526095.

Abbreviations

- snoRNA:

-

small nucleolar RNAs

- rRNA:

-

ribosomal RNA

- snRNA:

-

spliceosomal nuclear RNA

- tRNA:

-

transfer RNA

- UHG:

-

U snoRNA host gene

- SL RNA:

-

spliced-leader RNA

- pre-rRNA:

-

precursor ribosomal RNA

- bp:

-

basepairs

- dNTP:

-

deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate

- scaRNAs:

-

small Cajal body-specific RNA

- RIP:

-

Repeat-Induced Point Mutation

- gas5:

-

growth arrest-specific 5

- UTR:

-

untranslated region

- RT-PCR:

-

reversed transcript PCR

- cDNA:

-

complementary DNA

- CDS:

-

coding sequence.

References

Decatur WA, Fournier MJ: rRNA modifications and ribosome function. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002, 27 (7): 344-351.

Bachellerie JP, Cavaille J, Huttenhofer A: The expanding snoRNA world. Biochimie. 2002, 84 (8): 775-790.

Maden BEH: The numerous modified nucleotides in eukaryotic ribosomal RNA. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1990, 39: 241-303.

Kiss T: Small nucleolar RNAs: an abundant group of noncoding RNAs with diverse cellular functions. Cell. 2002, 109 (2): 145-148.

Dennis PP, Omer A: Small non-coding RNAs in Archaea. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005, 8 (6): 685-694.

Kiss-Laszlo Z, Henry Y, Bachellerie JP, Caizergues-Ferrer M, Kiss T: Site-specific ribose methylation of preribosomal RNA: a novel function for small nucleolar RNAs. Cell. 1996, 85 (7): 1077-1088.

Schattner P, Barberan-Soler S, Lowe TM: A computational screen for mammalian pseudouridylation guide H/ACA RNAs. RNA. 2006, 12 (1): 15-25.

Vitali P, Royo H, Seitz H, Bachellerie JP, Huttenhofer A, Cavaille J: Identification of 13 novel human modification guide RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31 (22): 6543-6551.

Chen CL, Liang D, Zhou H, Zhuo M, Chen YQ, Qu LH: The high diversity of snoRNAs in plants: identification and comparative study of 120 snoRNA genes from Oryza sativa. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31 (10): 2601-2613.

Barneche F, Gaspin C, Guyot R, Echeverria M: Identification of 66 box C/D snoRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana: extensive gene duplications generated multiple isoforms predicting new ribosomal RNA 2'-O-methylation sites. J Mol Biol. 2001, 311 (1): 57-73.

Qu LH, Meng Q, Zhou H, Chen YQ: Identification of 10 novel snoRNA gene clusters from Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29 (7): 1623-1630.

Lowe TM, Eddy SR: A computational screen for methylation guide snoRNAs in yeast. Science. 1999, 283 (5405): 1168-1171.

Schattner P, Decatur WA, Davis CA, Ares M, Fournier MJ, Lowe TM: Genome-wide searching for pseudouridylation guide snoRNAs: analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32 (14): 4281-4296.

Torchet C, Badis G, Devaux F, Costanzo G, Werner M, Jacquier A: The complete set of H/ACA snoRNAs that guide rRNA pseudouridylations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA. 2005, 11 (6): 928-938.

Li SG, Zhou H, Luo YP, Zhang P, Qu LH: Identification and functional analysis of 20 Box H/ACA small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Biol Chem. 2005, 280 (16): 16446-16455.

Liang XH, Hury A, Hoze E, Uliel S, Myslyuk I, Apatoff A, Unger R, Michaeli S: Genome-wide analysis of C/D and H/ACA-like small nucleolar RNAs in Leishmania major indicates conservation among trypanosomatids in the repertoire and in their rRNA targets. Eukaryot Cell. 2007, 6 (3): 361-377.

Liang XH, Uliel S, Hury A, Barth S, Doniger T, Unger R, Michaeli S: A genome-wide analysis of C/D and H/ACA-like small nucleolar RNAs in Trypanosoma brucei reveals a trypanosome-specific pattern of rRNA modification. RNA. 2005, 11 (5): 619-645.

Russell AG, Schnare MN, Gray MW: A large collection of compact box C/D snoRNAs and their isoforms in Euglena gracilis: structural, functional and evolutionary insights. J Mol Biol. 2006, 357 (5): 1548-1565.

Yang CY, Zhou H, Luo J, Qu LH: Identification of 20 snoRNA-like RNAs from the primitive eukaryote, Giardia lamblia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005, 328 (4): 1224-1231.

Omer AD, Lowe TM, Russell AG, Ebhardt H, Eddy SR, Dennis PP: Homologs of small nucleolar RNAs in Archaea. Science. 2000, 288 (5465): 517-522.

Matera AG, Terns RM, Terns MP: Non-coding RNAs: lessons from the small nuclear and small nucleolar RNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007, 8 (3): 209-220.

Tycowski KT, You ZH, Graham PJ, Steitz JA: Modification of U6 spliceosomal RNA is guided by other small RNAs. Mol Cell. 1998, 2 (5): 629-638.

Dennis PP, Omer A, Lowe T: A guided tour: small RNA function in Archaea. Mol Microbiol. 2001, 40 (3): 509-519.

Zemann A, op de Bekke A, Kiefmann M, Brosius J, Schmitz J: Evolution of small nucleolar RNAs in nematodes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34 (9): 2676-2685.

Liang XH, Xu YX, Michaeli S: The spliced leader-associated RNA is a trypanosome-specific sn(o) RNA that has the potential to guide pseudouridine formation on the SL RNA. RNA. 2002, 8 (2): 237-246.

Kishore S, Stamm S: The snoRNA HBII-52 regulates alternative splicing of the serotonin receptor 2C. Science. 2006, 311 (5758): 230-232.

Dong XY, Rodriguez C, Guo P, Sun X, Talbot JT, Zhou W, Petros J, Li Q, Vessella RL, Kibel AS, et al: SnoRNA U50 is a candidate tumor suppressor gene at 6q14.3 with a mutation associated with clinically significant prostate cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2008, 17 (7): 1031-1042.

Kiss-Laszlo Z, Henry Y, Kiss T: Sequence and structural elements of methylation guide snoRNAs essential for site-specific ribose methylation of pre-rRNA. EMBO J. 1998, 17 (3): 797-807.

Ganot P, Bortolin ML, Kiss T: Site-specific pseudouridine formation in preribosomal RNA is guided by small nucleolar RNAs. Cell. 1997, 89 (5): 799-809.

Ni J, Tien AL, Fournier MJ: Small nucleolar RNAs direct site-specific synthesis of pseudouridine in ribosomal RNA. Cell. 1997, 89 (4): 565-573.

Reichow SL, Hamma T, Ferre-D'Amare AR, Varani G: The structure and function of small nucleolar ribonucleoproteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35 (5): 1452-1464.

Huang ZP, Zhou H, He HL, Chen CL, Liang D, Qu LH: Genome-wide analyses of two families of snoRNA genes from Drosophila melanogaster, demonstrating the extensive utilization of introns for coding of snoRNAs. RNA. 2005, 11 (8): 1303-1316.

Liang D, Zhou H, Zhang P, Chen YQ, Chen X, Chen CL, Qu LH: A novel gene organization: intronic snoRNA gene clusters from Oryza sativa. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30 (14): 3262-3272.

Kruszka K, Barneche F, Guyot R, Ailhas J, Meneau I, Schiffer S, Marchfelder A, Echeverria M: Plant dicistronic tRNA-snoRNA genes: a new mode of expression of the small nucleolar RNAs processed by RNase Z. EMBO J. 2003, 22 (3): 621-632.

Davis RH, Perkins DD: Timeline: Neurospora: a model of model microbes. Nat Rev Genet. 2002, 3 (5): 397-403.

Galagan JE, Calvo SE, Borkovich KA, Selker EU, Read ND, Jaffe D, FitzHugh W, Ma LJ, Smirnov S, Purcell S, et al: The genome sequence of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Nature. 2003, 422 (6934): 859-868.

Liu N, Huang QJ, Zhou H, Liang YT, Yu CH, Qu LH: Identification, expression and functional analysis of U3 snoRNA genes from Neurospora crassa. Progress in Natural Science. 2009, 19 (2): 167-172.

Luo YP: RNomics in fission yeast: analysis of genomic organization and expression of box C/D snoRNAs from large scale screen of cDNA library. PhD thesis. 2004, Sun Yat-sen University, School of Life Science

Bi YZ, Qu LH, Zhou H: Characterization and functional analysis of a novel double-guide C/D box snoRNA in the fission yeast. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007, 354 (1): 302-308.

Zhou H, Chen YQ, Du YP, Qu LH: The Schizosaccharomyces pombe mgU6-47 gene is required for 2'-O-methylation of U6 snRNA at A41. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30 (4): 894-902.

Hirose T, Steitz JA: Position within the host intron is critical for efficient processing of box C/D snoRNAs in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001, 98 (23): 12914-12919.

Vincenti S, De Chiara V, Bozzoni I, Presutti C: The position of yeast snoRNA-coding regions within host introns is essential for their biosynthesis and for efficient splicing of the host pre-mRNA. RNA. 2007, 13 (1): 138-150.

Raho G, Barone V, Rossi D, Philipson L, Sorrentino V: The gas 5 gene shows four alternative splicing patterns without coding for a protein. Gene. 2000, 256 (1-2): 13-17.

Piekna-Przybylska D, Decatur WA, Fournier MJ: New bioinformatic tools for analysis of nucleotide modifications in eukaryotic rRNA. RNA. 2007, 13 (3): 305-312.

Liang XH, Liu Q, Fournier MJ: rRNA modifications in an intersubunit bridge of the ribosome strongly affect both ribosome biogenesis and activity. Mol Cell. 2007, 28 (6): 965-977.

Chow CS, Lamichhane TN, Mahto SK: Expanding the nucleotide repertoire of the ribosome with post-transcriptional modifications. ACS Chem Biol. 2007, 2 (9): 610-619.

Chakrabarti K, Pearson M, Grate L, Sterne-Weiler T, Deans J, Donohue JP, Ares M: Structural RNAs of known and unknown function identified in malaria parasites by comparative genomics and RNA analysis. RNA. 2007, 13 (11): 1923-1939.

Qu LH, Henras A, Lu YJ, Zhou H, Zhou WX, Zhu YQ, Zhao J, Henry Y, Caizergues-Ferrer M, Bachellerie JP: Seven novel methylation guide small nucleolar RNAs are processed from a common polycistronic transcript by Rat1p and RNase III in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 1999, 19 (2): 1144-1158.

Qu LH, Henry Y, Nicoloso M, Michot B, Azum MC, Renalier MH, Caizergues-Ferrer M, Bachellerie JP: U24, a novel intron-encoded small nucleolar RNA with two 12 nt long, phylogenetically conserved complementarities to 28S rRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995, 23 (14): 2669-2676.

Brown JW, Echeverria M, Qu LH: Plant snoRNAs: functional evolution and new modes of gene expression. Trends Plant Sci. 2003, 8 (1): 42-49.

Galagan JE, Selker EU: RIP: the evolutionary cost of genome defense. Trends Genet. 2004, 20 (9): 417-423.

Cambareri EB, Singer MJ, Selker EU: Recurrence of repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) in Neurospora crassa. Genetics. 1991, 127 (4): 699-710.

Watters MK, Randall TA, Margolin BS, Selker EU, Stadler DR: Action of repeat-induced point mutation on both strands of a duplex and on tandem duplications of various sizes in Neurospora. Genetics. 1999, 153 (2): 705-714.

Margolin BS, Garrett-Engele PW, Stevens JN, Fritz DY, Garrett-Engele C, Metzenberg RL, Selker EU: A methylated Neurospora 5S rRNA pseudogene contains a transposable element inactivated by repeat-induced point mutation. Genetics. 1998, 149 (4): 1787-1797.

Kinsey JA, Garrett-Engele PW, Cambareri EB, Selker EU: The Neurospora transposon Tad is sensitive to repeat-induced point mutation (RIP). Genetics. 1994, 138 (3): 657-664.

Ast G: How did alternative splicing evolve?. Nat Rev Genet. 2004, 5 (10): 773-782.

Modrek B, Lee C: A genomic view of alternative splicing. Nat Genet. 2002, 30 (1): 13-19.

Mironov AA, Fickett JW, Gelfand MS: Frequent alternative splicing of human genes. Genome Res. 1999, 9 (12): 1288-1293.

Chomczynski P, Sacchi N: Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987, 162 (1): 156-159.

Gu AD, Zhou H, Yu CH, Qu LH: A novel experimental approach for systematic identification of box H/ACA snoRNAs from eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33 (22): e194-

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ: Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990, 215 (3): 403-410.

Maden BEH, Corbett ME, Heeney PA, Pugh K, Ajuh PM: Classical and novel approaches to the detection and localization of the numerous modified nucleotides in eukaryotic ribosomal RNA. Biochimie. 1995, 77 (1-2): 22-29.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Xiao-Hong Chen, Qiao-Juan Huang and Yi-Ling Chen for technical assistances. This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30570398, 30830066), the funds from the Ministry of Education of China and Guangdong Province (No. IRT0447, NSF05200303) and the National Basic Research Program (No. 2005CB724600).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Authors' contributions

NL, LHQ and HZ conceived the study and contributed to manuscript writing. NL performed the experiments. YTL assisted in partial experiments of Northern blot analysis and mapping of ribose methylation. ZDX and DGG assisted in the computational searching for box C/D and box H/ACA snoRNA genes, respectively. CLC and JHY assisted in the data analysis of box C/D and box H/ACA snoRNA genes, respectively. CHY and PS helped to draft the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12864_2009_2399_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional file 1: The sequences and accession numbers of the box C/D snoRNAs identified from the N. crassa genome. The data showedall the box C/D snoRNA sequences identified from N. crassa. (PDF 49 KB)

12864_2009_2399_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Additional file 2: The sequences and accession numbers of the box H/ACA snoRNAs identified from the N. crassa genome. The data showed all box H/ACA snoRNA sequences identified from N. crassa. (PDF 26 KB)

12864_2009_2399_MOESM3_ESM.pdf

Additional file 3: Secondary structures of partial N. crassa box H/ACA snoRNAs. The figures present the secondary structures of six representative box H/ACA snoRNAs from N. crassa. (PDF 27 KB)

12864_2009_2399_MOESM4_ESM.pdf

Additional file 4: Potential base-pairing between box C/D snoRNAs and rRNA (A), snRNA (B) or tRNA (C). The data showed the functional analysis of the N. crassa box C/D snoRNAs. (PDF 39 KB)

12864_2009_2399_MOESM5_ESM.pdf

Additional file 5: Potential base-pairing between box H/ACA snoRNAs and rRNAs. The data showed the functional analysis of the N. crassa box H/ACA snoRNAs. (PDF 25 KB)

12864_2009_2399_MOESM6_ESM.pdf

Additional file 6: Strategy for construction of the specialized cDNA libraries enriched in N. crassa box C/D and box H/ACA snoRNAs. The figure shows that the strategy and pipeline for construction of the N. crassa box C/D snoRNA library (A) and box H/ACA snoRNA library (B). (PDF 12 KB)

12864_2009_2399_MOESM7_ESM.pdf

Additional file 7: Sequences of oligonucleotides and primers used in this study. The data listed all the sequences of oligonucleotides and primers used in this study. (PDF 52 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, N., Xiao, ZD., Yu, CH. et al. SnoRNAs from the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa: structural, functional and evolutionary insights. BMC Genomics 10, 515 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-10-515

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-10-515