Abstract

Background

Reliable marking systems are critical to the prospective field release of transgenic insect strains. This is to unambiguously distinguish released insects from wild insects in the field that are collected in field traps, and tissue-specific markers, such as those that are sperm-specific, have particular uses such as identifying wild females that have mated with released males. For tephritid fruit flies such as the Mexican fruit fly, Anastrepha ludens, polyubiquitin-regulated fluorescent protein body markers allow transgenic fly identification, and fluorescent protein genes regulated by the spermatocyte-specific β2-tubulin promoter effectively mark sperm. For sterile male release programs, both marking systems can be made male-specific by linkage to the Y chromosome.

Results

An A. ludens wild type strain was genetically transformed with a piggyBac vector, pBXL{PUbnlsEGFP, Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3}, having the polyubiquitin-regulated EGFP body marker, and the β2-tubulin-regulated DsRed.T3 sperm-specific marker. Autosomal insertion lines effectively expressed both markers, but a single Y-linked insertion (YEGFP strain) expressed only PUbnlsEGFP. This insertion was remobilized by transposase helper injection, which resulted in three new autosomal insertion lines that expressed both markers. This indicated that the original Y-linked Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3 marker was functional, but specifically suppressed on the Y chromosome. The PUbnlsEGFP marker remained effective however, and the YEGFP strain was used to create a sexing strain by translocating the wild type allele of the black pupae (bp+) gene onto the Y, which was then introduced into the bp- mutant strain. This allows the mechanical separation of mutant female black pupae from male brown pupae, that can be identified as adults by EGFP fluorescence.

Conclusions

A Y-linked insertion of the pBXL{PUbnlsEGFP, Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3} transformation vector in A. ludens resulted in male-specific expression of the EGFP fluorescent protein marker, and was integrated into a black pupae translocation sexing strain (T(YEGFP/bp+), allowing the identification of male adults when used in sterile male release programs for population control. A unique observation was that expression of the Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3 sperm-specific marker, which was functional in autosomal insertions, was specifically suppressed in the Y-linked insertion. This may relate to the Y chromosomal regulation of male-specific germ-line genes in Drosophila.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A critical component to any prospective field release of a transgenic insect strain is a reliable and robust marking system. Foremost, this is to unambiguously identify the transgenic insects, and to distinguish them from insects in the field, especially in traps that monitor the effectiveness of the release program [1]. For tephritid fruit flies, fluorescent protein markers regulated by the constitutive polyubiquitin (PUb) gene promoter are quite effective since the PUb promoter is active in all cell types throughout development (see [2–4]), and for the Caribbean fruit fly, PUb-DsRed.T3 can be visualized unambiguously and detected by PCR in deceased flies maintained in two types of liquid field traps for up to three weeks [5]. A high priority for SIT programs is evaluating the number of wild females that have mated with released sterile males, which can be achieved by sperm-specific markers. Using the spermatocyte-specific β2-tubulin promoter [6] to regulate either EGFP or DsRed, fluorescent sperm markers detectable specifically in the female spermathecae, have been developed for several tephritid and mosquito species [7–11].

The Mexican fruit fly, Anastrepha ludens, has been successfully transformed using piggyBac transposon vectors [12], and specifically by those having fluorescent protein marker genes regulated by the Drosophila polyubiquitin and A. suspensa β2-tubulin (Asβ2tub) promoters [13]. In selecting for dual-marked pBXL{PUbnlsEGFP, Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3} transformants, we noted that in autosomal integrations, as determined by segregation analysis, males and females expressed EGFP in the body while only males expressed testis-specific DsRed. However, one line expressed EGFP specifically in males and not in females, suggesting a Y-linked integration, but the expected testis-specific expression of DsRed was not apparent. Here we provide data showing that remobilization of the Y-linked insertion to autosomal sites restores Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3 expression, indicating that Y-specific suppression of the Asβ2-tubulin promoter may be occurring.

Sex-specific fluorescent protein markers, such as those linked to the Y-chromosome (or Z-chromosome in moths), or whose expression is controlled by a sex-specific promoter or intron-splicing mechanism, can be used for sexing strains previous to release [14, 15]. This is particularly advantageous for SIT [16] where sterilization and release of females with males is highly inefficient. However, current sorting systems for fluorescent-marked larvae (or eggs) are not efficient enough for most current fruit fly sterile release programs [9], and automated sexing systems usually rely on pupal color markers (which is combined with an embryonic temperature-sensitive lethal system only in Ceratitis capitata [17]). Sex-specificity is achieved in these strains by having the wild type color marker gene translocated to the Y-chromosome, while the homozygous autosomal recessive mutation exists in both males and females [18, 19]. Thus, the normal wild type pupal color in males can be distinguished from the mutant color phenotype in females, which has been achieved for the mexfly using the black pupae (bp) mutation [20, 21]. While this system is highly effective for sex separation previous to release, identifying released male adults still depends upon fluorescent powders that are not totally effective, and a health risk for workers [22]. Therefore, male-specific fluorescent protein markers are still the most effective and safe system for identifying released males in the field. Here we describe the creation of strains having both male-specific expression of bp+ for pupal sexing, and PUbnlsEGFP for identification in field traps.

Results

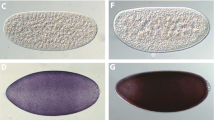

YEGFP vector remobilization . Segregation analysis of lines transformed with the piggyBac transformation vector, pBXL{PUbnlsEGFP, Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3} (see Additional file 1) [13], indicated that one line, YEGFP, was Y-linked due to PUbnlsEGFP fluorescent marker expression being limited to males, and segregation analysis showing male-specific inheritance (Figure 1). However, the sperm-specific expression of Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3, observed in four other autosomal insertion lines, was not observed in the Y-linked line (Fig. 1A-C). The structural integrity of the Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3 vector construct in YEGFP was verified by PCR sequencing (see Additional file 2), indicating that this was not due to a mutation or rearrangement.

Y-linked and autosomal fluorescent marker expression in A. ludens transformed with pBXL{ PUbnlsEGFP, Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3 }. The brightfield (BF; A, D, G) and epifluorescent EGFP (GFP2; B, E, H), and DsRed (TXR; C, F, I) phenotypes of: a YEGFP male (left) and female (right) shown in panels A, B, and C; an autosomal insertion (unmapped) strain male (left) and female (right) shown in panels D, E, and F; and testes from a YEGFP and autosomal insertion strain male shown in panels G, H, and I. See Methods for details on epifluorescent microscopy and filter sets.

Therefore, to determine whether suppression of Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3 was due to a chromosomal position effect the vector was re-mobilized by injection of phsp-pBac transposase helper plasmid into 832 embryos from the YEGFP hemizygous line. Of these, 40 G0 surviving males were individually crossed to three wild type females, resulting in three G1 lines where adult males expressed both thoracic EGFP and testis-specific DsRed fluorescence (Fig. 1D-F), whereas the remaining 37 fertile matings expressed only EGFP. Segregation analysis of crosses to wild type indicated that the DsRed fluorescent lines resulted from remobilization into autosomal loci. In addition to PCR transgene sequencing in the YEGFP line and ME8 autosomal line, derived from the vector remobilization in YEGFP (see Additional file 2), this verifies the functional integrity of the original Y-linked vector insertion, and suggests that Y chromosome suppression of Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3 expression had occurred. Transposon vector remobilizations typically result in local insertions (or 'hops') into sites within the same linkage group (which facilitates transposon mutagenesis strategies) [23]. It is not unlikely that local hops occurred in this remobilization as well, which would not have been recognized if Asβ2-tubulin promoter suppression was a general attribute of Y linkage, and not limited to a specific locus (or loci).

Translocation Y-EGFP/bp+ strain development . To create a black pupae sexing strain marked with male-specific PUbnlsEGFP expression to identify released males in traps, the YEGFP strain was used as a host strain for a bp+ translocation induced by γ-irradiation as described in Methods. From YEGFP irradiated pupae, 900 adult males were screened, from which five potential lines were selected where all females had the mutant black pupae (bp-) phenotype, and all males had the brown pupae (bp+) wild type phenotype, in addition to green fluorescence observed under epifluorescent optics (Table 1; Figure 2).

Phenotypes of T(YEGFP/ bp+ ) pupal and adult males and females. A. ludens T(YEGFP/bp+) male bp+ brown pupa (A) and male adult (B) under epifluorescent GFP optics, and a female bp- black pupa (C) and female adult (D) under brightfield optics. All T(YEGFP/bp+) males express the wild type brown pupal and EGFP phenotype, while all females express the mutant black pupal phenotype and lack EGFP fluorescence (not shown).

Evaluation of the T(YEGFP/bp+) strains . Life fitness parameters for the five translocation strains were evaluated by observing the survival of 1,000 embryos through life stages from larval hatching to adulthood. Overall survival from the egg stage to adulthood was 17.6% in line T(YEGFP/bp+)-1 to 36.4% in line T(YEGFP/bp+)-4, which was comparable to 38.1% survival in the Tapachula-7 control strain already being mass-reared for SIT programs. Line T(YEGFP/bp+)-3 had a similar survival rate of 33.4% (Table 2).

The integrity of translocation strains can often be compromised by recombination, especially between sequences within the translocated autosome. When this occurs in sequences proximal to the centromere, the mutant and WT alleles can be exchanged resulting in a breakdown of the sexing system. To assess such recombination in the T(YEGFP/bp+) lines, they were maintained without selection for four generations and then screened for an exchange of the bp+ and bp- phenotypes in males and females. In the T(YEGFP/bp+)-1 and -2 lines recombinant individuals were not detected, while the T(YEGFP/bp+)-3, -4 and -5 lines exhibited 0.28% (1 male bp-), 0.23% (1 female bp+) and 1.74% (4 male bp-; 2 female bp+) recombinant frequencies, respectively. These frequencies are considerably higher than the 0.05% frequency for Tapachula-7 [21], and is most likely a function of the distance between the bp allele and translocation breakpoint, which is expected to increase with distance [24]. Since the strains exhibiting recombinants were also the most highly viable, induction of an inversion in this region to suppress recombination, as has been achieved for the medfly VIENNA-8 translocation sexing strain [24], may be considered. Selection of additional translocation lines having strong viability and minimal recombination is also feasible.

Discussion

Here we report the creation of an A. ludens transgenic line with a piggyBac transformation vector that includes fluorescent protein markers useful for identifying released males in the field and wild females that have mated with the released males. Notably, the vector insertion site is Y-linked, so that a sexing line could be created by translocating the wild type allele for the bp mutation onto the Y chromosome, allowing the separation of black pupal (bp-) females from brown pupal (bp+) males during rearing.

Use of pupal color markers in Y-translocation strains has been an efficient means of creating sexing strains in tephritid flies [18, 19]. Recessive mutations resulting in pupal phenotypes exhibiting darker or lighter coloration than wild type are relatively common, and translocations of their wild type allele to the male-specific Y chromosome are straightforward to create and select. Relatively inexpensive rice sorters can then be used to efficiently separate large numbers of wild type male pupae from mutant females. One drawback is that, typically, pupal markers do not confer an adult phenotype (or one that is easily identifiable), so that identification of released males depends upon the use of fluorescent powders that can be unreliable (due to loss from grooming or transfer to wild males), and a health risk to workers involved in rearing and release [22]. Thus, the male-specific Y-linked fluorescent protein transgene marker provides a reliable means of identifying released male adults in traps, a secondary means of verifying pupal sex if cuticle coloration is ambiguous, and a rapid means of identifying putative recombinants (having an EGFP/bp- phenotype). If Y-linked fluorescence is detectable in embryos or early stage larvae, it may be eventually useful as a means to select males by automated fluorescence-based sorters early in development [9], thereby eliminating females previous to rearing to the pupal stage, which is costly and inefficient.

The Y-linked transformant line was originally selected during a previous transformation experiment, where both the polyubiquitin-regulated EGFP body color marker and the β2-tubulin-regulated sperm marker were easily identifiable and distinguishable in autosomal integrations [13]. However, while the Y-linked PUbnlsEGFP marker was strongly expressed and reliably detected in males, the Asβ2tub-DsRed marker was not visibly detectable, which we presume is the result of suppressed transcription since its sequence integrity has been verified. This is unfortunate since it eliminates the ability to identify females that have mated with the transgenic males by identifying fluorescent sperm stored in their spermathecae. However, remobilization of the Y-linked integration to autosomal sites restored Asβ2tub-DsRed expression, which may be similarly achieved in T(YEGFP/bp+) strains by a local remobilization of the pBXL{PUbnlsEGFP, Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3} vector to the translocated autosome, thereby maintaining male-specificity. Alternatively, an autosome carrying the vector transgene could be crossed into the translocation line, thus providing both fluorescent markers.

Beyond an unusual phenomenon, the Y-specific suppression of the Asβ2tubulin promoter may, nevertheless, have important implications for how the male germ-line is regulated by the Y chromosome in tephritids. Position effect variegation (PEV), resulting from suppression of gene expression typically affecting euchromatic genes positioned proximal to or within heterochromatin, is well documented [25]. Differential promoter regulation by PEV is less well established, but evidence exists in D. melanogaster for the Y chromosome having a general suppressive effect on PEV [26–28], and for specific regions of the Y chromosome having a positive trans-activator function specifically for transcription of male germ-line genes [29]. If this type of activity occurs in mexfly, it is conceivable that the transgene vector integration may have disrupted Y-activation of the Asβ2-tubulin promoter, but if so, other germ-line genes (including the native A. ludens β2-tubulin gene) also should have been affected resulting in diminished fertility, which was not apparent. Remobilization of the transgene could have also resulted in local hops within the Y, with the expectation that a site or region-specific position effect on the original insertion would be less effective in some remobilized Y-linked lines, which was also not apparent. Thus far, the specific suppression of a Y-linked β2-tubulin gene promoter, or any other promoter, is a unique observation. It will be important to determine whether this is the result of a gene expression regulatory function that is specific to a particular Y-linked locus or region, or a chromosome-wide effect for the chromosome, and whether other male germ-line specific genes are similarly affected.

Methods

Insect strains . The black pupae (bp-) mutant strain was originally isolated from A. ludens flies mass-reared at the MOSCAFRUT facility. The pBXL{PUbnlsEGFP, Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3} transgenic strains were created as previously described [13], with the YEGFP strain having a Y-linked integration based on segregation analysis. Transgenic flies were screened by epifluorescence microscopy for DsRed (TXR filter: ex: 560/40; em: 610 LP) and EGFP (GFP2 filter; ex: 480/40, em: 510 LP) fluorescence. The wild type Chiapas strain was originally collected from infested fruit in the state of Chiapas, Mexico, and the genetic sexing strain "Tapachula-7" was created as described [21].

Plasmids . The pBXL{PUbnlsEGFP, Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3} piggyBac transformation vector (plasmid #389) used to create the YEGFP strain was described previously (see Additional file 1) [10, 13]. The piggyBac transposase helper plasmid, phsp-pBac, used to remobilize pBXL{PUbnlsEGFP, Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3} in YEGFP, was described previously [30].

pBXL{PUbnlsEGFP, Asβ2-tub-DsRed.T3} remobilization . Remobilization of the pBXL{PUbnlsEGFP, Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3} vector in YEGFP followed typical germ-line transformation procedures for Anastrepha species [3, 13], except that YEGFP G0 embryos were injected solely with 500 µg/ml of phsp-pBac helper plasmid. Eclosed G0 adults were backcrossed in small groups to Chiapas wild type host flies, with resulting G1 adult progeny examined under epifluorescence optics for EGFP and DsRed expression. Autosomal or sex-linkage of vector insertions were determined by outcrossing G2 and G3 males and females to wild type. Chromosomal insertions of pBXL{PUbnlsEGFP, Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3} determined to be Y-linked due to male-specific marker expression were designated as YEGFP.

YEGFP /bp+ translocation strain . Pupae from the YEGFP; bp+/bp+ strain were γ-irradiated with 30 Gy using Cobalt60, with newly eclosed males crossed to homozygous bp-/bp-mutant females. Phenotypic wild type (brown) F1 males, having the genotypes YEGFP; bp+/bp- or T(YEGFP, bp+); Df(bp+)/bp-, were backcrossed to bp-/bp- females in single pair matings, with F2 T(YEGFP, bp+) translocation lines identified by those having all males eclosing from brown pupae (bp+) (expected in all lines), but where all females eclosed from black pupae (bp-), versus black and brown female pupae generated from non-translocation males. F2 females inheriting the Df(bp+) autosome from translocation males were lethal due to aneuploidy, and thus only bp-/bp- females survived. Male-specific expression of PUbnlsEGFP also indicated that the pBXL{PUbnlsEGFP, Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3} Y-linked insertion was not deleted by the translocation, and these lines were designated as T(YEGFP/bp+).

Life fitness test . All translocation lines were inbred with approximately 1,000 eggs from each line put on artificial diet in groups of 100 eggs, with larvae and pupae collected and recorded [31]. Pupae were sexed by pupal color that was verified after adult eclosion. The same procedure was applied as a control to the Chiapas wild type and Tapachula-7 strains. Statistical analysis was carried out comparing the YEGFP translocation strains, the Tapachula-7 strain and the wild type A. ludens strain by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey-Kramer tests [32].

PCR analysis. To verify the integrity of the Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3 marker transgene in autosomal and Y-linked vector integrations, genomic DNA from the autosomal ME8 and Y-linked T(YEGFP, bp+) lines was isolated for PCR reactions using the primer pair P15 (GGTGGAGCTCCAGCTTTTGTTCC) / MFS-10 (ACGACCGCGTGAGTCAAAATGACG) and Platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen). PCR was performed on both genomic samples and the control AH389 vector plasmid using the following conditions: 1 min at 95°C; 5 cycles of 15 s at 94°C, 20 s at 65°C (-2°C/cycle), 2.5 min at 72°C; 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 45 s at 56°C, 2.5 min at 72°C; and 3 min at 72°C. All 2.4 kb fragments were subcloned in pCR4 vector (Invitrogen) and sequenced at Macrogen using the oligos M13F, M13R and P17 (CCGTCGGAGGGGAAGTTCACG). Multiple sequence alignments were performed in Geneious 7.1 (Biomatters, Ltd.) using the standard Geneious Alignment algorithm.

References

Handler AM: Use of the piggyBac transposon for germ-line transformation of insects. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2002, 32 (10): 1211-1220. 10.1016/S0965-1748(02)00084-X.

Bevis BJ, Glick BS: Rapidly maturing variants of the Discosoma red fluorescent protein (DsRed). Nature biotechnology. 2002, 20 (1): 83-87. 10.1038/nbt0102-83.

Handler AM, Harrell RA: Transformation of the Caribbean fruit fly, Anastrepha suspensa, with a piggyBac vector marked with polyubiquitin-regulated GFP. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2001, 31 (2): 199-205. 10.1016/S0965-1748(00)00119-3.

Handler AM, Harrell RA: Polyubiquitin-regulated DsRed marker for transgenic insects. Biotechniques. 2001, 31 (4): 824-828. 820

Nirmala X, Olson S, Holler T, Cho K, Handler AM: A DsRed fluorescent protein marker under polyubiquitin promoter regulation allows visual and amplified gene detection of transgenic Caribbean fruit flies in liquid traps. BioControl. 2011, 56 (3): 333-340. 10.1007/s10526-011-9347-9.

Michiels F, Gasch A, Kaltschmidt B, Renkawitz-Pohl R: A 14 bp promoter element directs the testis specificity of the Drosophila beta 2 tubulin gene. The EMBO journal. 1989, 8 (5): 1559-1565.

Scolari F, Schetelig MF, Bertin S, Malacrida AR, Gasperi G, Wimmer EA: Fluorescent sperm marking to improve the fight against the pest insect Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann; Diptera: Tephritidae). New biotechnology. 2008, 25 (1): 76-84. 10.1016/j.nbt.2008.02.001.

Scolari F, Schetelig M, Gabrieli P, Siciliano P, Gomulski L, Karam N, Wimmer E, Malacrida A, Gasperi G: Insect transgenesis applied to tephritid pest control. Journal of Applied Entomology. 2008

Catteruccia F, Benton JP, Crisanti A: An Anopheles transgenic sexing strain for vector control. Nature biotechnology. 2005, 23 (11): 1414-1417. 10.1038/nbt1152.

Zimowska GJ, Nirmala X, Handler AM: The beta2-tubulin gene from three tephritid fruit fly species and use of its promoter for sperm marking. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2009, 39 (8): 508-515. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2009.05.004.

Smith RC, Walter MF, Hice RH, O'Brochta DA, Atkinson PW: Testis-specific expression of the β2 tubulin promoter of Aedes aegypti and its application as a genetic sex-separation marker. Insect molecular biology. 2007, 16 (1): 61-71. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00701.x.

Condon KC, Condon GC, Dafa'alla TH, Forrester OT, Phillips CE, Scaife S, Alphey L: Germ-line transformation of the Mexican fruit fly. Insect molecular biology. 2007, 16 (5): 573-580. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00752.x.

Meza JS, Nirmala X, Zimowska GJ, Zepeda-Cisneros CS, Handler AM: Development of transgenic strains for the biological control of the Mexican fruit fly, Anastrepha ludens. Genetica. 2011, 139 (1): 53-62. 10.1007/s10709-010-9484-6.

Condon KC, Condon GC, Dafa'alla TH, Fu G, Phillips CE, Jin L, Gong P, Alphey L: Genetic sexing through the use of Y-linked transgenes. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2007, 37 (11): 1168-1176. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.07.006.

Schetelig MF, Handler AM: Y-Linked Markers for Improved Population Control of the Tephritid Fruit Fly Pest, Anastrepha suspensa. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology. 2013

Knipling EF: Possibilities of insect control or eradication through the use of sexually sterile males. Journal of Economic Entomology. 1955, 48: 459-462. 10.1093/jee/48.4.459.

Robinson AS, Franz G, Fisher K: Genetic sexing strains in the medfly, Ceratitis capitata: development, mass rearing and field application. Trends in Entomology. 1999, 2: 81-104.

McInnis D, Leblanc L, Mau R: Melon fly (Diptera: Tephritidae) genetic sexing: all-male sterile fly releases in Hawaii. Proceedings of the Hawaiian Entomological Society. 2007, 39: 105-110.

McCombs SD, Lee SG, Saul SH: Translocation-based genetic sexing system to enhance the sterile insect technique against the melon fly (Diptera: Tephritidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 1993, 86 (5): 651-654. 10.1093/aesa/86.5.651.

Zepeda-Cisneros CS, Meza JS, García-Martínez V, Ibanez J, Zacharopoulou A, Franz G: Development, genetic and cytogenetic analyses of genetic sexing strains of the Mexican fruit fly Anastrepha ludens Loew. BMC Genetics. 2014, in press

Orozco D, Meza JS, Zepeda S, Solis E, Quintero-Fong JL: Tapachula-7, a new genetic sexing strain of the Mexican fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae): sexual compatibility and competitiveness. Journal of Economic Entomology. 2013, 106 (2): 735-741. 10.1603/EC12441.

Hagler JR, Jackson CG: Methods for marking insects: current techniques and future prospects. Annual Review of Entomology. 2001, 46: 511-543. 10.1146/annurev.ento.46.1.511.

Tower J, Karpen GH, Craig N, Spradling AC: Preferential transposition of Drosophila P elements to nearby chromosomal sites. Genetics. 1993, 133 (2): 347-359.

Franz G, Gencheva E, Kerremans P: Improved stability of genetic sex-separation strains for the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata. Genome / National Research Council Canada = Genome / Conseil national de recherches Canada. 1994, 37 (1): 72-82. 10.1139/g94-009.

Elgin SC, Reuter G: Position-effect variegation, heterochromatin formation, and gene silencing in Drosophila. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2013, 5 (8): a017780-

Branco AT, Tao Y, Hartl DL, Lemos B: Natural variation of the Y chromosome suppresses sex ratio distortion and modulates testis-specific gene expression in Drosophila simulans. Heredity. 2013, 111 (1): 8-15. 10.1038/hdy.2013.5.

Jiang PP, Hartl DL, Lemos B: Y not a dead end: epistatic interactions between Y-linked regulatory polymorphisms and genetic background affect global gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2010, 186 (1): 109-118. 10.1534/genetics.110.118109.

Dimitri P, Pisano C: Position effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster: relationship between suppression effect and the amount of Y chromosome. Genetics. 1989, 122 (4): 793-800.

Zhang P, Timakov B, Stankiewicz RL, Turgut IY: A trans-activator on the Drosophila Y chromosome regulates gene expression in the male germ line. Genetica. 2000, 109 (1-2): 141-150.

Handler AM, Harrell RA: Germline transformation of Drosophila melanogaster with the piggyBac transposon vector. Insect molecular biology. 1999, 8 (4): 449-457. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1999.00139.x.

FAO/IAEA/USDA: Manual for Product Quality Control and Shipping Procedures for Sterile Mass Reared Tephritid Fruit Flies Version 5 International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Austria. Vienna: IAEA. 2003, 1-84.

Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ: Biometry: the principles and practice of statistics in biological research. 1995, New York, NY: W.H. Freeman and Co., 3

Acknowledgements

This research benefited from discussions at the International Atomic Energy Agency Coordinated Research Project, "Development and Evaluation of Improved Strains of Insect Pests for SIT", and was supported by the Programa Moscafrut/ SAGARPA-IICA, the 'Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT)' (no. 229669; to JSM, SZ-C), the Emmy Noether program of the German Research Foundation (SCHE 1833/1-1; MFS) and the LOEWE Center for Insect Biotechnology and Bioresources (to MFS), and the USDA-NIFA-Biotechnology Risk Assessment Grant Program (no. 2011-39211-30769; to AMH). We also thank Tanja Rehling for excellent technical assistance.

This article has been published as part of BMC Genetics Volume 15 Supplement 2, 2014: Development and evaluation of improved strains of insect pests for SIT. The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://www.biomedcentral.com/bmcgenet/supplements/15/S2.

Publication of this supplement was funded by the International Atomic Energy Agency. The peer review process for articles published in this supplement was overseen by the Supplement Editors in accordance with BioMed Central's peer review guidelines for supplements. The Supplement Editors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JSM, AMH, MFS, and CSZ-C conceived of the study, its design and coordination, and JSM carried out the transformation and vector remobilization studies and creation of the translocation strain. AMH created the vector and helper plasmids and MFS carried out PCR analysis. AMH, MFS and JSM wrote the manuscript, for which the final draft was read and approved by all authors.

Electronic supplementary material

12863_2014_1314_MOESM2_ESM.tif

Additional file 2: Integrity of Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3 marker transgene. A multiple sequence alignment of PCR sequenced transgene vector fragments from genomic DNA from the Y-linked YEGFP and autosomal ME8 transformant lines, and the pBXL{PUbnlsEGFP, Asβ2tub-DsRed.T3} plasmid vector. This verifies the integrity of the marker transgene in the two transformant lines based on 100% identity among the sequences. (TIF 2 MB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Meza, J.S., Schetelig, M.F., Zepeda-Cisneros, C.S. et al. Male-specific Y-linked transgene markers to enhance biologically-based control of the Mexican fruit fly, Anastrepha ludens(Diptera: Tephritidae). BMC Genet 15 (Suppl 2), S4 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-15-S2-S4

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-15-S2-S4