Abstract

Background

We previously established a congenic mouse strain with TALLYHO/Jng (TH) donor segment on chromosome 6 in a C57BL/6 (B6) background that harbors an obesity quantitative trait locus, tabw2. The B6.TH-tabw2 congenic mice developed increased adiposity that became exacerbated upon feeding a high fat-high sucrose (HFS) diet. To fine map the tabw2, in this study we generated and characterized subcongenic lines with smaller TH donor segments.

Results

We fixed four subcongenic lines, with maximum size of donor segment retained in the lines ranging from 10.8 – 92.5 Mb. For mapping, all the subcongenic mice, along with B6.TH-tabw2 congenic and B6-homozygous control mice were fed either chow or HFS diets, and their post-mortem fat pads were weighed. Mice were also characterized for energy expenditure, respiratory exchange ratio, locomotor activity, and food intake. As previously reported, B6.TH-tabw2 congenic mice showed a significantly larger fat mass than controls on both diets. On chow, a subcongenic line retaining the distal region of the TH donor congenic interval exhibited significantly larger fat mass than B6-homozygous controls, and comparable that to B6.TH-tabw2 congenic mice. Two nested subcongenic lines within that region suggested that the effect of tabw2 on obesity could be attributed to at least two subloci. On HFS diets, on the other hand, all the subcongenic mice had significantly larger fat mass than controls without genotype differences, but none of them had fat mass as large as the original congenic mice. This possibly implicates that further genetic complexity involves in the effect of tabw2 on diet-induced obesity. Significantly reduced locomotor activity was exhibited in B6.TH-tabw2 congenic and subcongenic mice compared to controls when animals were fed HFS diets. B6.TH-tabw2 congenic mice, but not subcongenic mice, also had significantly increased food intake on HFS diets.

Conclusions

It appears that at least two subloci explaining the tabw2 effect under chow feeding map to the distal region of the congenic interval, whereas the diet-induced obesity mediated by tabw2 is attributed to more complex genetic mechanism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Obesity is characterized by excessive storage of fat in adipose tissue [1]. The etiology of human obesity involves genetic predisposition from multiple genes and nongenetic risk factors such as sedentary lifestyle and energy-dense diets [2–5]. Closely resembling this disease in humans, polygenic mouse model of obesity with natural variants offers a valuable alternative for studying genetic architecture of obesity [6, 7]. One powerful application available with mouse models is construction of congenic mice. Congenic mouse strains are virtually identical except for a small donor chromosomal segment harboring a gene of interest [8, 9]. Therefore, congenic mice allow the multiple genes underlying polygenic obesity to be dissected into individual genes for further study.

TALLYHO/Jng (TH) mice are a polygenic inbred model of type 2 diabetes and obesity [10]. Previously, we have established a congenic mouse strain that harbors a TH-derived chromosome 6 genomic segment containing an obesity quantitative trait locus (QTL), tabw2 (TALLYHO associated body weight 2), on a B6 background [11]. This B6.TH-tabw2 congenic strain develops increased adiposity that becomes exacerbated upon feeding high fat-high sucrose (HFS) diets. In this study, we generated and characterized subcongenic lines of mice with smaller TH donor segments to fine map the tabw2 QTL. Unlike conventional linkage mapping, such as with F2 cross, multiple mice with the same recombination can be analyzed from subcongenic lines, resulting in more accurate estimation of the phenotype conferred by the QTL. This subcongenic approach has been successfully used for refining the location of QTLs and identification of susceptibility genes for diabetes and obesity [12–14].

Results

Generation of subcongenic lines of mice for tabw2QTL on chromosome 6

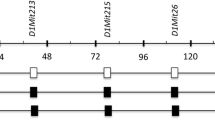

To fine map the tabw2 QTL, subcongenic lines of mice with different segments of the TH donor congenic interval were generated from B6.TH-tabw2 congenic mice (Figure 1). These subcongenic lines captured the full congenic region, except the end-proximal portion of ~20-Mb. The maximal TH interval retained in the lines, marked as the most proximal and distal primers with known B6 homozygous genotypes for a given donor segment, ranged from 10.8 (line D) – 92.5 (line B) Mb. The minimal TH interval retained in the lines, marked as the most proximal and distal primers with known TH homozygous genotypes for a given donor segment, ranged from 1.4 (line D) – 57.2 (line B) Mb. Alleotype of the genomic region between maximal and minimal interval primers is unknown.

B6.TH- tabw2 congenic and subcongenic intervals at the tabw2 locus on mouse chromosome 6. SSLP primers shown at the top were used to allelotype the congenic interval. The open and filled boxes represent a B6 and TH allele, respectively. Mean fat pad weights (g) are listed for each group under two diets for comparison (detailed phenotypic data are presented in Table 1).

Mapping of the adiposity trait using subcongenic mice

For subcongenic mapping, male B6.TH-tabw2 congenic, subcongenic, and B6-homozygous control mice were fed either chow or HFS diets, and body and fat pad weights were measured. As previously reported [11], B6.TH-tabw2 congenic mice showed a significantly larger fat pad weight than B6-homozygous control mice on both diets (Table 1). Therefore, we used fat pad weight as the phenotypic trait for fine mapping.

We first compared subcongenic lines A and B that overlap and together cover the largest subcongenic donor region. Under chow feeding, the mean value of fat pad weight in line A was not statistically different from that in B6-homozygous control mice, while line B had significantly greater fat pad weight than controls, comparable to that in B6.TH-tabw2 congenic mice (Table 1). These results suggest that the tabw2 candidate region is most likely located within the unique segment retained in line B, extending distally from the marker D6Mit29 (Figure 1). Interestingly, lines C and D, two nested subcongenic lines of the line B, but not overlapping each other, exhibited fat pad weights numerically intermediate between B6-homozygous control and B6.TH-tabw2 congenic mice (Table 1). This may suggest that the effect of tabw2 on obesity could be attributed to at least two subloci, named tabw2a (associated with line C) and tabw2b (associated with line D).

Under HFS diet feeding, on the other hand, all the subcongenic lines had significantly greater fat pad weight than B6-homozygous control mice, without genotype differences among the lines (Table 1). However, none of the subcongenic lines had fat pad weight that was as great as B6.TH-tabw2 congenic mice.

Indirect calorimetry, locomotor activity, and food intake

In order to elucidate metabolic mechanisms driving increased fat mass in the obesity mediated by tabw2, B6.TH-tabw2 congenic, subcongenic, and B6-homozygous control mice fed either chow or HFS diets were allowed to acclimate to Comprehensive Laboratory Animal Monitoring System (CLAMS) for 24 hours followed by 48-hours continuous monitoring of heat production, respiratory exchange ratio (RER), locomotor activity, and food intake. The 2-day averages are presented in Table 2. Since body composition of tabw2 mice varies mainly in adipose tissue [11], which exerts a limited contribution to total energy expenditure [15, 16], CLAMS data were calculated per animal rather than correcting for body weight.

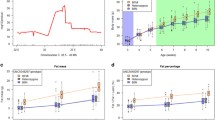

Energy expenditure, determined as heat production (kcal/hour), was not largely different across the groups of mice fed chow, with the lowest value in line B. When animals were fed HFS diets, energy expenditure elevated in all mice compared to chow feeding, but there was no genotype effect.

Fuel source preference, as RER, was not significantly different between groups of mice fed chow. When animals were placed on HFS diets, RER values were generally lower compared to chow, demonstrating that whole body substrate metabolism was shifted towards fat oxidation. Notably, subcongenic line A mice showed significantly lower value of RER than other groups on HFS diets; this may be related with the significantly lower food intake in this group.

Locomotor activity, determined by the ambulatory count over a 24-hour period, was not significantly different among the groups of mice fed chow, with the lowest value in line B. On HFS diets, however, B6.TH-tabw2 congenic and subcongenic mice showed significantly reduced locomotor activity compared to B6-homozygous control mice.

Food intake, determined as kcal consumed/day, was significantly higher (~ 26%) in B6.TH-tabw2 congenic mice compared to B6-homozygous control mice on HFS diets. However, none of the subcongenic lines showed differences compared to control mice, except line A showed significantly lower caloric intake than controls. Despite the isocaloric or hypocaloric intake, the fat mass of subcongenic mice was ~1.4 – 1.6-fold higher than B6-homozygous control mice, potentially suggesting higher energy retention efficiency in subcongenic mice than controls.

Discussion

In the current study, we conducted subcongenic mapping to fine map the tabw2 QTL on chromosome 6 captured in B6.TH-tabw2 congenic mice. We also assessed metabolic components regulating the energy homeostasis of B6.TH-tabw2 congenic, subcongenic, and B6-homozygous control mice.

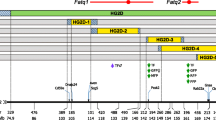

Our findings suggest that there are possibly at least two subloci, named tabw2a and tabw2b, responsible for the tabw2-mediated obesity on chow. The maximal interval for tabw2a would be a 38.5-Mb region between D6Mit29 and D6Mit254. This region contains multiple obesity QTLs previously mapped, including Efw (epididymal fat weight) identified in F2 mice (NSY x C3H/He) [17], Bw18 (body weight QTL 18) in SMXA mice [18], Pbwg8 (postnatal body weight growth 8) in backcross mice [F1(B6 x CAST) x CAST] [19], Egrm (early growth rate, maternal effect 2) in F2 mice (SM/J x LG/J) [20], Pfat2 (predicted fat percentage 2) in F2 mice (B6 x DBA/2J) [21], Obq14 (obesity QTL 14) in F2 mice (NZO x SM) [22], and Obwq3 (obesity and body weight QTL 3) in F2 mice (SM/J x NZB/BINJ) [23]. Tabw2b resides within a maximal interval of 10.8-Mb. A couple of obesity QTLs were previously mapped in this region, including Wta2 (weight adult 2) identified in F2 mice (LG/J x SM/J) [24] and Bwtq10 (body weight QTL 10) in F2 mice (SM/J x NZB/BINJ [23]. The concurrence of obesity QTLs in these regions may suggest that candidate gene(s) for the tabw2 may be involved in obesity in other mouse models.

The present data also demonstrate a potential genetic complexity underlying the diet-induced obesity associated with tabw2. Unlike shown in chow feeding, there was no net effect of tabw2a and tabw2b on the fat pad weight in subcongenic line B mice fed HFS diets. At this stage the nature of tabw2 effect on diet-induced obesity is unknown: however, it could arise from complex interactions among multiple subloci and/or interactions between the subloci and other genes that interact but have no effect on their own. Potentially, these interactions may occur in a context-dependent manner [25] involving a certain environment, such as HFS diets. Several examples of this complex genetic architecture for obesity QTLs have previously been reported and include a QTL on mouse chromosome 7 [26] and Wg2a-d (weight gain in high growth mice 2a-d) [27] and Pbwg1.1-8 (postnatal body weight growth1.1-8) [28] on mouse chromosome 2. Also, we cannot rule out the possibility that the end-proximal portion of the congenic interval, not captured in subcongenic lines in this study, might be required for the full congenic effect on diet-induced obesity. Previously, we performed fine mapping of the tabw2 locus by standard linkage analysis using F2 mice fed HFS diets and gained only a rough map position of 15 cM [11], probably due to the genetic complexity underlying the diet-induced obesity in tabw2 congenic mice. Nonetheless, the 15 cM interval overlaps the tabw2a interval.

Using CLAMS experiments, we report that modest, but significant, hypoactivity emerged in B6.TH-tabw2 congenic and subcongenic mice when animals were placed on HFS diets. This modest decrease in activity, however, did not significantly change the energy expenditure as assessed by heat production calculated from VO2. Therefore, it appears that these VO2 measurements in indirect calorimetric system reflect relative energy expenditure rather than absolutely accurate measurements as previously discussed [29]. Similar observations of little effect of changes in locomotor activity on energy expenditure were previously reported in other indirect calorimetric studies using mice [30, 31]. Overfeeding usually results in compensatory increases in energy expenditure and physical activity in an attempt to maintain constant body mass [32]. Therefore, an inability to increase locomotor activity in response to HFS diets over time could lead to the diet-induced obesity mediated by tabw2, although it does not fully explain the full congenic phenotype. Currently, the mechanism by which decreases in locomotor activity in the diet-induced obesity associated with tabw2 is unknown. Possibilities include lack of motivation or the presence of physical limitations accompanied by increased body fat mass.

Unlike the reduced locomotor activity, increased food intake was only shown in B6.TH-tabw2 congenic mice fed HFS diets. Therefore, we speculate that the increased food intake might be a contributing factor for the full congenic phenotype of adiposity. However, as food intake data are not presently available on chow, we cannot conclude whether the hyperphagia is constitutive or disrupted compensatory response to HFS diets.

Conclusions

We have created subcongenic lines, with smaller TH donor segments from the tabw2 congenic interval, which develop detectable phenotypes, thus narrowing target intervals for positional cloning. The data presented here also identify potential pathological mechanisms underlying the diet-induced obesity mediated by tabw2. Future studies to further define subloci of tabw2 and functional studies involving candidate genes could provide useful knowledge in understanding genetic contributions in human obesity.

Methods

Animals and diets

All mice were allowed free access to food and water in a temperature and humidity controlled room with a 12-hour light/dark cycle. At 4 weeks of age, mice were weaned onto standard rodent chow (Purina 5001, PMI Nutrition, Brentwood, MO, USA) or HFS diets (32% kcal from fat and 25% kcal from sucrose) (12266B, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) and maintained. Detailed composition of chow and HFS diets are presented in Table 3. All animal studies were carried out with the approval of Marshall University Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation.

Generation of subcongenic lines of mice

B6.TH-tabw2 congenic mice and B6-homozygous control mice were previously established [11]. First, a B6.TH-tabw2 congenic strain was crossed with B6-homozygous control strain, and the resultant F1 hybrids were intercrossed to produce F2 progeny. The F2 mice were then genotyped with simple sequence length polymorphism (SSLP) primers spaced throughout the congenic interval to search for crossovers. When a desirable crossover was identified within the region of interest, the recombinants were backcrossed to B6-homozygous control strain to duplicate the fragment. Male and female heterozygous backcrossed mice were then intercrossed to derive progeny that are TH homozygous for the region of interest and B6 homozygous for the rest of the chromosome.

Genotyping by PCR

Genomic DNA was extracted from tail tips using proteinase K [11] and two series of salt precipitation steps. The DNA was PCR amplified using SSLP primers synthesized (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) based on sequences from Mouse Genome Informatics (http://www.informatics.jax.org). The thermal cycle consisted of 95°C for 2 min, followed by 49 cycles of 94°C (20 sec), 50°C (30 sec) and 72°C (40 sec) and a final extension at 72°C (7 min). Amplified products were electrophoretically separated on 3% MetaPhor agarose (50184, Lonza, Rockland, ME, USA)/1% agarose (0710-500G, Amresco, Solon, OH, USA) gels in 0.5 x tris-borate-EDTA buffer, pH 7.4. The DNA was visualized by ethidium bromide (E-1510, Sigma-Aldrich) staining.

Subcongenic mapping of the adiposity trait

For subcongenic mapping, B6.TH-tabw2 congenic, sucongenic, and B6-homozygous control mice fed either chow or HFS diets were weighed and killed at 14–17 weeks of age (non-fasting). Five white fat pads (inguinal, epididymal, mesenteric, retroperitoneal including perirenal, and subscapular) were then collected and weighed. The sum of these five pad weights was used as the adiposity trait.

Indirect calorimetry, locomotor activity, and food intake

At 14–15 weeks of age, food intake, energy expenditure, RER, and locomotor activity were measured using an eight-chamber CLAMS (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA). In this system, total oxygen consumption (VO2) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2) were measured, and VO2 was converted to individual heat production (kcal/hour) by Columbus software. This software calculates the heat production by multiplying the calorific value by the observed . RER is the ratio between the VCO2 and , reflecting the daily whole-body oxidation rate of carbohydrate and fat; ~ 0.7 (complete reliance on fat oxidation) and 1.0 (complete reliance on carbohydrate oxidation). A system of infrared beams detects movement of animals in CLAMS, and locomotor activity was determined as ambulatory count, the number of times different beams were broken in either the x- or y-axes during an interval. The CLAMS allows continuous measurement of food intake by each animal. All mice were acclimatized to monitoring cages for 24 hours prior to an additional 48 hours of recordings under the regular 12-hour light–dark cycle.

Statistical analysis

All response variables were analyzed using ANOVA (SAS version 9.3, Cary, NC), with group, diet, and interaction effects in the model. Differences among means were sliced by diet (group differences only compared within diets), and tested using Fisher's LSD at P < 0.05. All data are presented as least squares means ± SEM.

References

Ahima RS: Digging deeper into obesity. J Clin Invest. 2011, 121: 2076-2079. 10.1172/JCI58719.

Qi L, Cho YA: Gene-environment interaction and obesity. Nutr Rev. 2008, 66: 684-694. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00128.x.

Oldham S: Obesity and nutrient sensing TOR pathway in flies and vertebrates: functional conservation of genetic mechanisms. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2011, 22: 45-52. 10.1016/j.tem.2010.11.002.

Herrera BM, Keildson S, Lindgren CM: Genetics and epigenetics of obesity. Maturitas. 2011, 69: 41-49. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.02.018.

Ramachandrappa S, Farooqi IS: Genetic approaches to understanding human obesity. J Clin Invest. 2011, 121: 2080-2086. 10.1172/JCI46044.

Speakman J, Hambly C, Mitchell S, Król E: The contribution of animal models to the study of obesity. Lab Anim. 2008, 42: 413-432. 10.1258/la.2007.006067.

Warden CH, Fisler JS: Obesity: from animal models to human genetics to practical applications. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2010, 94: 373-389.

Rogner UC, Avner P: Congenic mice: cutting tools for complex immune disorders. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003, 3: 243-252. 10.1038/nri1031.

Brockmann GA, Bevova MR: Using mouse models to dissect the genetics of obesity. Trends Genet. 2002, 18: 367-376. 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02703-8.

Kim JH, Sen S, Avery CS, Simpson E, Chandler P, Nishina PM, Churchill GA, Naggert JK: Genetic analysis of a new mouse model for non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Genomics. 2001, 74: 273-286. 10.1006/geno.2001.6569.

Kim JH, Stewart TP, Zhang W, Kim HY, Nishina PM, Naggert JK: Type 2 diabetes mouse model TallyHo carries an obesity gene on chromosome 6 that exaggerates dietary obesity. Physiol Genomics. 2005, 22: 171-181. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00197.2004.

Clee SM, Yandell BS, Schueler KM, Rabaglia ME, Richards OC, Raines SM, Kabara EA, Klass DM, Mui ET, Stapleton DS, Gray-Keller MP, Young MB, Stoehr JP, Lan H, Boronenkov I, Raess PW, Flowers MT, Attie AD: Positional cloning of Sorcs1, a type 2 diabetes quantitative trait locus. Nat Genet. 2006, 38: 688-693. 10.1038/ng1796.

Chiu S, Kim K, Haus KA, Espinal GM, Millon LV, Warden CH: Identification of positional candidate genes for body weight and adiposity in subcongenic mice. Physiol Genomics. 2007, 31: 75-85. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00267.2006.

Scherneck S, Nestler M, Vogel H, Blüher M, Block MD, Diaz MB, Herzig S, Schulz N, Teichert M, Tischer S, Al-Hasani H, Kluge R, Schürmann A, Joost HG: Positional cloning of zinc finger domain transcription factor Zfp69, a candidate gene for obesity-associated diabetes contributed by mouse locus Nidd/SJL. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5: e1000541-10.1371/journal.pgen.1000541.

Butler AA, Kozak LP: A recurring problem with the analysis of energy expenditure in genetic models expressing lean and obese phenotypes. Diabetes. 2010, 59 (2): 323-329. 10.2337/db09-1471.

Himms-Hagen J: On raising energy expenditure in ob/ob mice. Science. 1997, 276 (5315): 1132-1133. 10.1126/science.276.5315.1132.

Ueda H, Ikegami H, Kawaguchi Y, Fujisawa T, Yamato E, Shibata M, Ogihara T: Genetic analysis of late-onset type 2 diabetes in a mouse model of human complex trait. Diabetes. 1999, 48: 1168-1174. 10.2337/diabetes.48.5.1168.

Kaput J, Klein KG, Reyes EJ, Kibbe WA, Cooney CA, Jovanovic B, Visek WJ, Wolff GL: Identification of genes contributing to the obese yellow Avy phenotype: caloric restriction, genotype, diet x genotype interactions. Physiol Genomics. 2004, 18: 316-324. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00065.2003.

Ishikawa A, Namikawa T: Mapping major quantitative trait loci for postnatal growth in an intersubspecific backcross between C57BL/6J and Philippine wild mice by using principal component analysis. Genes Genet Syst. 2004, 79: 27-39. 10.1266/ggs.79.27.

Wolf JB, Vaughn TT, Pletscher LS, Cheverud JM: Contribution of maternal effect QTL to genetic architecture of early growth in mice. Heredity (Edinb). 2002, 89: 300-310. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800140.

Keightley PD, Morris KH, Ishikawa A, Falconer VM, Oliver F: Test of candidate gene–quantitative trait locus association applied to fatness in mice. Heredity (Edinb). 1998, 81: 630-637. 10.1046/j.1365-2540.1998.00450.x.

Taylor BA, Wnek C, Schroeder D, Phillips SJ: Multiple obesity QTLs identified in an intercross between the NZO (New Zealand obese) and the SM (small) mouse strains. Mamm Genome. 2001, 12: 95-103. 10.1007/s003350010254.

Stylianou IM, Korstanje R, Li R, Sheehan S, Paigen B, Churchill GA: Quantitative trait locus analysis for obesity reveals multiple networks of interacting loci. Mamm Genome. 2006, 17: 22-36. 10.1007/s00335-005-0091-2.

Cheverud JM, Vaughn TT, Pletscher LS, Peripato AC, Adams ES, Erikson CF, King-Ellison KJ: Genetic architecture of adiposity in the cross of LG/J and SM/J inbred mice. Mamm Genome. 2001, 12: 3-12. 10.1007/s003350010218.

Mackay TF, Stone EA, Ayroles JF: The genetics of quantitative traits: challenges and prospects. Nat Rev Genet. 2009, 10: 565-577.

Diament AL, Warden CH: Multiple linked mouse chromosome 7 loci influence body fat mass. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004, 28: 199-210.

Farber CR, Medrano JF: Dissection of a genetically complex cluster of growth and obesity QTLs on mouse chromosome 2 using subcongenic intercrosses. Mamm Genome. 2007, 18: 635-645. 10.1007/s00335-007-9046-0.

Ishikawa A, Kim EH, Bolor H, Mollah MB, Namikawa T: A growth QTL (Pbwg1) region of mouse chromosome 2 contains closely linked loci affecting growth and body composition. Mamm Genome. 2007, 18: 229-239. 10.1007/s00335-007-9009-5.

Kaiyala KJ, Schwartz MW: Toward a more complete (and less controversial) understanding of energy expenditure and its role in obesity pathogenesis. Diabetes. 2011, 60: 17-23. 10.2337/db10-0909.

Bates SH, Dundon TA, Seifert M, Carlson M, Maratos-Flier E, Myers MG: LRb-STAT3 signaling is required for the neuroendocrine regulation of energy expenditure by leptin. Diabetes. 2004, 53: 3067-3073. 10.2337/diabetes.53.12.3067.

Choi SJ, Yablonka-Reuveni Z, Kaiyala KJ, Ogimoto K, Schwartz MW, Wisse BE: Increased energy expenditure and leptin sensitivity account for low fat mass in myostatin-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011, 300: E1031-E1037. 10.1152/ajpendo.00656.2010.

Novak CM, Levine JA: Central neural and endocrine mechanisms of non-exercise activity thermogenesis and their potential impact on obesity. J Neuroendocrinol. 2007, 19: 923-940. 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01606.x.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Michael A. Pellizzon for providing information about composition of HFS diets. This work was supported by NIH/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease Grant R01DK077202 and in part by American Heart Association Grant 0855300E.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

TPS and MNA constructed the subcongenic lines. DU and KDD did additional genotyping and KDD maintained the mouse colony. TPS phenotyped mice for mapping. TPS and XM did CLAMS experiments. AMS conducted statistical analysis of the data. JHK conceived the study and was primarily responsible for its coordination and design. AMS and JHK drafted the manuscript, tables and figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Stewart, T.P., Mao, X., Aqqad, M.N. et al. Subcongenic analysis of tabw2obesity QTL on mouse chromosome 6. BMC Genet 13, 81 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-13-81

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-13-81