Abstract

Background

Lineage-specific genes, the genes that are restricted to a limited subset of related organisms, may be important in adaptation. In parasitic organisms, lineage-specific gene products are possible targets for vaccine development or therapeutics when these genes are absent from the host genome.

Results

In this study, we utilized comparative approaches based on a phylogenetic framework to characterize lineage-specific genes in the parasitic protozoan phylum Apicomplexa. Genes from species in two major apicomplexan genera, Plasmodium and Theileria, were categorized into six levels of lineage specificity based on a nine-species phylogeny. In both genera, lineage-specific genes tend to have a higher level of sequence divergence among sister species. In addition, species-specific genes possess a strong codon usage bias compared to other genes in the genome. We found that a large number of genus- or species-specific genes are putative surface antigens that may be involved in host-parasite interactions. Interestingly, the two parasite lineages exhibit several notable differences. In Plasmodium, the (G + C) content at the third codon position increases with lineage specificity while Theileria shows the opposite trend. Surface antigens in Plasmodium are species-specific and mainly located in sub-telomeric regions. In contrast, surface antigens in Theileria are conserved at the genus level and distributed across the entire lengths of chromosomes.

Conclusion

Our results provide further support for the model that gene duplication followed by rapid divergence is a major mechanism for generating lineage-specific genes. The result that many lineage-specific genes are putative surface antigens supports the hypothesis that lineage-specific genes could be important in parasite adaptation. The contrasting properties between the lineage-specific genes in two major apicomplexan genera indicate that the mechanisms of generating lineage-specific genes and the subsequent evolutionary fates can differ between related parasite lineages. Future studies that focus on improving functional annotation of parasite genomes and collection of genetic variation data at within- and between-species levels will be important in facilitating our understanding of parasite adaptation and natural selection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Comparative genomics has revealed pronounced differences in gene content across species [1]. In an early analysis of eight microbial genomes, 20–56% of the genes in a genome were shown to not have high similarity to any sequence in public databases [2]. Initially these genes were referred to as orphan genes, or ORFans, because they correspond to stretches of open reading frame in bacterial genomes that have no known relationship to other sequences. As more eukaryote genome sequences become available, the term 'lineage-specific gene' is gaining in popularity because one can specify the 'lineage specificity' of a gene to describe its phylogenetic distribution [3].

Newly evolved genes may be important for adaptation and generation of diversity [4]. For example, the protozoan parasite Cryptosporidium parvum possesses a set of nucleotide salvage genes that are unique among all apicomplexans surveyed to date [5]. Acquisition of the nucleotide salvage pathway from a proteobacterial source as well as other sources apparently facilitated loss of genes involved in de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis, rendering this parasite entirely dependent on the host for both its purines and pyrimidines. Characterization of these lineage-specific genes not only leads to a better understanding of the parasite's biology but also provides a promising therapeutic target against an important parasite, since blocking the nucleotide salvage pathway can inhibit parasite growth but not harm its human host [5].

Currently, there are several hypotheses regarding the origin of lineage-specific genes. The first model invokes the process of horizontal gene transfer, in which organisms acquire genes from other distantly related species. This mechanism can create lineage-specific genes that are not shared by closely related organisms, as in the example of nucleotide salvage enzymes in C. parvum [5]. Previous studies have shown that horizontal gene transfer is an important force for genome evolution in bacteria [6–8], unicellular eukaryotes [9], and multicellular eukaryotes [10].

The second model is based on gene duplication followed by rapid sequence divergence [11, 12]. Based on the observation that the sequence divergence rate is positively correlated with lineage specificity in a diverse set of organisms [3, 11–14], Alba and Castresana [12] proposed that newly duplicated genes may be released from selective constraint and accumulate mutations at a faster rate. While most of the mutations may be deleterious and lead to loss of function in one copy [15], it is also possible that one of the copies can acquire new functions and become a novel gene in the genome. However, whether gene duplication followed by rapid divergence is truly an important mechanism of generating lineage-specific genes is still under debate. Elhaik et al. [16] suggested that the correlation between divergence rate and lineage specificity may simply be an artifact, stemming from our inability to identify homologs of fast-evolving genes across distantly related taxa based on sequence similarity searches. However, a recent simulation study by Alba and Castresana [17] demonstrated that sequence similarity searches performed at the amino acid level can reliably detect fast-evolving genes due to the rate heterogeneity among sites.

In addition to the two main models discussed above, other explanations for the origin of lineage-specific genes such as de novo creation from non-coding sequences [18, 19], exon-shuffling [20, 21], intracellular gene transfer between organellar and nuclear genomes [9], and differential gene loss [22] also have been proposed. However, the relative importance of various forces that generate lineage-specific genes remains largely unknown.

While erroneous annotation has also been proposed as one explanation for the abundance of lineage-specific genes [23, 24], expression data [25, 26] and nucleotide substitution patterns [24, 27] suggest that many lineage-specific genes are indeed functional and not annotation artifacts. Unfortunately, understanding the biological function of these genes is difficult due to the lack of homologs in model organisms to use for functional characterization. As a result, a large percentage of the lineage-specific genes that have been identified to date are annotated as hypothetical proteins of unknown function.

In this study, we aim to characterize the lineage-specific genes in a group of unicellular eukaryotes from the phylum Apicomplexa, including several important pathogens of humans and animals. The most infamous member of this phylum is the causative agent of malaria, Plasmodium, which causes more than one million human deaths per year globally [28]. Other important lineages include Cryptosporidium that causes cryptosporidiosis in humans and animals [29, 30], Theileria that causes tropical theileriosis and East Coast fever in cattle [31, 32], and Toxoplasma that causes toxoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients and congenitally infected fetuses [33]. The availability of genome sequences from these apicomplexan species has provided us with new and exciting opportunities to study their genome evolution. Improved knowledge of the lineage-specific genes in these important parasites can lead to a better understanding of their adaptation history and possibly identification of novel therapeutic targets.

Results

Inference of the species tree

We based our comparative analyses on a phylogenetic framework in order to infer the lineage specificity of individual genes. Among the nine species included in the data set (seven apicomplexans as well as two outgroup ciliates), we identified 83 single-copy genes that contain at least 100 alignable amino acid sites to infer the species tree (see Methods for details; a list of these 83 genes is provided in Additional file 1). Based on the concatenated alignment of these 83 genes (with 24,494 aligned amino acids sites), we infer a species tree with strong bootstrap support (Figure 1). This tree is consistent with our prior understanding of apicomplexan relationships based on morphology and development [34], rDNA analyses [35, 36], and multigene phylogenies [37, 38].

The apicomplexan species tree. Maximum likelihood tree generated from the concatenated alignment of 83 single-copy genes (24,494 aligned amino acid sites). Two free-living ciliates, Paramecium tetraurelia and Tetrahymena thermophila, are included as the outgroup to root the tree. Labels above branches indicate the level of clade support inferred by 100 bootstrap replicates.

Phylogenetic distribution of orthologous genes

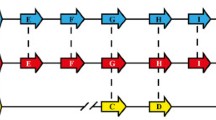

Using the species tree (Figure 1) as the foundation, we characterized the phylogenetic distribution of orthologous gene clusters among the apicomplexan genomes analyzed (Figure 2, Table 1). The orthologous gene identification was performed using OrthoMCL [39] based on sequence similarity searches with an additional step of Markov Clustering [40] to improve sensitivity and specificity (see Methods for details). Our results indicated that many genes are genus-specific, ranging from approximately 30% of the genes in Plasmodium and Theileria up to about 45% in Cryptosporidium.

Phylogenetic distribution of orthologous gene clusters. The numbers after species name abbreviation (see Table 1) indicate the total number of annotated protein coding genes in the genome. The numbers above a branch and proceeded by a '+' sign indicate the number of orthologous gene clusters that are uniquely present in all daughter lineages; the numbers below a branch and proceeded by a '-' sign indicate the number of orthologous gene clusters that are uniquely absent. For example, on the internal branch that leads to the two Plasmodium species, 1,645 gene clusters contain sequences from both Pf and Pv but not any other species present on the tree. Similarly, there are 22 gene clusters that contain sequences from all species except Pf and Pv. Note that a gene cluster may contain more than one sequence from a species if paralogs are present in the genome. The levels refer to the degree of lineage specificity; genes in level 1 are shared by all species on the tree and genes in level 6 are species-specific.

We selected Plasmodium falciparum and Theileria annulata for further investigations of lineage-specific genes. The asymmetrical topology of the species tree allows categorization of the genes in these two species into six levels of lineage specificity (Figure 2), yielding the highest resolution in determining the lineage specificity of a gene. The least specific genes at level 1, denoted as Pf1 for those in the P. falciparum genome and Ta1 for those in the T. annulata genome, are shared by all nine species analyzed, including two free-living ciliates; the most specific genes at level 6, denoted as Pf6 for those in the P. falciparum genome and Ta6 for those in the T. annulata genome, are species-specific. Together these six sets of genes account for 77% of annotated P. falciparum proteins (4,141/5,411) and 84% of annotated T. annulata proteins (3,191/3,795). Genes that are shared by a non-monophyletic group (e.g., shared by P. falciparum and T. annulata but are not found in any other species) are omitted from the following analyses. Additionally, the two species pairs, P. falciparum-P. vivax and T. annulata-T. parva, may have comparable divergence times in the range of approximately 80–100 million years [41, 42] such that we can directly compare the properties of their species-specific genes. Finally, within the two focal genera, P. falciparum and T. annulata have a higher level of completeness of genome assembly than their sister species and thus are better choices for determining the chromosomal location of the lineage-specific genes.

Sequence divergence

The two Plasmodium species, P. falciparum and P. vivax, differ greatly in their base composition. In the coding region, P. falciparum has a (G + C) content of 24% while P. vivax has a (G + C) content of 46%. Estimates of d N (the number of nonsynonymous substitutions per nonsynonymous site) and d S (the number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site) are not reliable due to the extreme AT-bias in the P. falciparum genome. The average d S calculated from 4,159 P. falciparum-P. vivax sequence pairs is 45.7. For this reason, we quantified sequence divergence at the amino acid level based on the protein distance calculated by TREE-PUZZLE [43]. We found that the level of sequence divergence between sister taxa is positively correlated with the lineage specificity of a gene (Figure 3). The same trend is observed in both species-pairs. Compared to the two Plasmodium species, the Theileria species-pair has a lower level of sequence divergence. Level 6 genes are not included in the sequence divergence result because they are species-specific and have no orthologous sequence in the sister species for comparison.

We identified 1,701 genes that are single copy in both Theileria species and are reasonably conserved for substitution rate analysis at the nucleotide level (i.e., d S <= 1). Consistent with the sequence divergence measured at the amino acid level, nucleotide substitution rates are higher in genes with higher lineage specificity (Table 2). We do not find strong evidence of any gene under positive selection (i.e., d N /d S ratio > 1, data not shown).

(G + C) content and relative codon bias

The average (G + C) content at the third codon position (i.e., (G+C3)) increases with lineage specificity in P. falciparum (Figure 4), suggesting that phylogenetically conserved genes are biased toward AT-rich codons in this extremely AT-rich genome. In T. annulata, the opposite trend is observed; genes with high lineage specificity have a lower (G + C) content at the third codon position (Figure 4).

We used the relative codon bias developed by Karlin et al. [44] to compare the differences in codon usage between different gene sets within each species (Table 3). In both P. falciparum and T. annulata, the level 6 (i.e., species-specific) genes exhibit a high level of deviation with regard of their codon preference compared to the other gene sets (see Methods for details). In P. falciparum, the average pairwise difference in all comparisons is 0.049 and the mean pairwise difference involving Pf6 genes is 0.102 (Table 3A). In T. annulata, the average pairwise difference in all comparison is 0.098 and the mean pairwise difference involving Ta6 genes is 0.183 (Table 3B).

Functional analyses based on annotation

As expected, most of the phylogenetically conserved genes have functional annotation or have at least one identifiable protein domain (Table 4). As the phylogenetic distribution of a gene becomes more restricted, it is more likely to be annotated as a hypothetical protein. Functional analysis based on available gene annotation indicates that most conserved genes (levels 1 and 2) are responsible for basic cellular processes (e.g., DNA replication, transcription, translation, etc), while most genus- and species-specific genes (levels 5 and 6) are hypothetical proteins of unknown function (see Additional files 2 and 3). Despite the poor annotation of genus- and species-specific genes, 87% of level 5 genes and 72% of level 6 genes in P. falciparum have expression data available based on oligonucleotide microarrays [26]. This result suggests that most of the hypothetical proteins are real genes and not annotation artifacts.

The two focal lineages in our analysis, Plasmodium and Theileria, exhibit one interesting difference in terms of the phylogenetic distribution of surface antigens. We found that surface antigens are species-specific in Plasmodium and genus-specific in Theileria. All members of the three large surface antigen protein families in P. falciparum genome, including 161 rifin, 74 PfEMP1, and 35 stevor, are found in the Pf6 list and have no ortholog in P. vivax. Of the 163 T. annulata proteins that contain FAINT, a protein domain that associates with proteins exported to the host cell [31], 116 are in the Ta5 list (i.e., shared by T. annulata and T. parva) and only 28 are in the Ta6 list (i.e., specific to T. annulata).

In P. falciparum 41% of the genus-specific proteins and 62% of the species-specific proteins contain a putative signal peptide or at least one predicted transmembrane domain (Table 4), which suggests that these proteins may be exported to the host cell or present on the surface of the parasite or its vacuole. This result is consistent with the hypothesis that lineage-specific genes in apicomplexan parasites are likely to be involved in host-parasite interactions and thus, potentially adaptation.

Chromosomal location

Analysis of chromosomal location demonstrated that most species-specific genes in P. falciparum are located near chromosome ends (see Figure 5 for one example chromosome and Additional file 4 for all 14 chromosomes). In T. annulata (see Figure 6 for one example chromosome and Additional file 5 for all four chromosomes), we observed a similar pattern that the regions adjacent to chromosome ends are devoid of the phylogenetically conserved genes (cf. Figures 5B and 6B). However, unlike the pattern found in P. falciparum, most of the species-specific genes in T. annulata (i.e., Ta6) are distributed across the entire length of chromosomes and are not enriched in the regions adjacent to chromosome ends (cf. Figures 5A and 6A).

Chromosomal location of genes in Plasmodium falciparum. Chromosomal location of genes on P. falciparum chromosome 10. See Additional file 4 for views of all 14 chromosomes in this species. The level of lineage specificity is as defined in Figure 2. A. View of entire chromosome 10 (MAL10). B. Close-up view of the first 200 kb of chromosome 10.

Chromosomal location of genes in Theileria annulata. Chromosomal location of genes on T. annulata chromosome 2. See Additional file 5 for views of all four chromosomes in this species. The level of lineage specificity is as defined in Figure 2. A. View of entire chromosome 2. B. Close-up view of the first 200 kb of chromosome 2.

To quantify the pattern of gene distribution on chromosomes, we calculated the distance of each gene to the nearest chromosome end. For each set of genes (levels 1 through 6 in each species), we utilized (1) the average distance to the nearest chromosome end and (2) the minimal distance to the nearest chromosome end (i.e., the minimal found in a given gene set) for this analysis. In P. falciparum, the average distance scales with chromosome size and the species-specific genes (i.e., Pf6) are closer to chromosome ends (Figure 7A). In contrast, minimal distance does not scale with chromosome size (Figure 7B). For all chromosomes, the minimal distances of phylogenetically conserved genes from the chromosome ends (i.e., Pf1 through Pf4) are larger than 50–100 kb. This result indicates that the regions that are occupied exclusively by genus- and species-specific genes are proportionally larger in smaller chromosomes. Consistent with this observation, three of the smallest chromosomes in P. falciparum (i.e., MAL1, MAL2, and MAL4) have many more species-specific genes than random expectation (Chi-square test d.f. = (6 gene sets -1) * (14 chromosomes - 1) = 65, P-value = 1e-12).

Average and minimal distance of mapped genes to chromosome end. The level of lineage specificity is as defined in Figure 2. A. Average distance to chromosome end in Plasmodium falciparum. B. Minimum distance to chromosome end in P. falciparum. C. Average distance to chromosome end in Theileria annulata. B. Minimum distance to chromosome end in T. annulata.

In T. annulata, genes with different levels of lineage specificity have similar average distances to chromosome ends (Figure 7C). This result corroborates the visual pattern in Figure 6A that species-specific genes are distributed across the entire length of a chromosome, in contrast to the clustering near chromosome ends observed in P. falciparum (Figure 5A). For all four chromosomes in T. annulata, the regions that are adjacent to chromosome ends and devoid of phylogenetically conserved genes (i.e., Ta1 through Ta4) are approximately 20–40 kb (Figure 7D), a distance smaller than in P. falciparum. Unlike the pattern found in P. falciparum in which species-specific genes are closer to chromosome ends than genus-specific genes, genus- and species-specific genes in T. annulata (i.e., Ta5 and Ta6) have similar minimal distances in all four chromosomes (Figure 7D).

In both P. falciparum and T. annulata, genes located near chromosome ends have a higher level of sequence divergence relative to its ortholog in the sister species at the amino acid level (Figure 8). This trend is observed in genes with different levels of lineage specificity and is stronger in T. annulata.

Amino acid sequence divergence and chromosomal location. Plot of amino acid sequence divergence as a function of the distance to the nearest chromosome end. A. Plasmodium falciparum. B. Theileria annulata. The black lines in both panels (i.e., Pf1-5 in panel A and Ta1-5 in panel B) refer to the combined results from genes with five different levels of lineage specificity and are included as the background reference. Error bars indicate standard errors.

Discussion

We identified a pattern in which lineage-specific genes have a higher level of sequence divergence among sister species in a group of important protozoan parasites. This result is consistent with previous studies in bacteria [13], fungi [3], and animals [11, 12, 14]. Now we further confirm that this pattern also holds true in a protistan phylum, suggesting that it may be universal across much of the tree-of-life. Results from functional analyses agree with our intuitive expectation that conserved genes are involved in basic cellular functionalities and are well annotated. A large number of the lineage-specific genes (at the species level in Plasmodium and the genus level in Theileria) are found to be putative surface antigens that the parasites use to interact with their hosts. This result supports the hypothesis that lineage-specific genes may be important in adaptation [4]. In addition, the physical distance of a gene to the nearest chromosome end is correlated with the level of sequence divergence.

We found three contrasting properties of lineage-specific genes between two major apicomplexan lineages. First, families of surface antigens are species-specific in Plasmodium but genus-specific in Theileria. Second, most of the species-specific genes are located in sub-telomeric regions in P. falciparum but no such pattern exists in T. annulata. Third, the (G + C) content at the third codon position increases with lineage specificity in P. falciparum but decreases in T. annulata. Taken together, these results suggest that the mechanisms of generating lineage-specific genes and their subsequent evolutionary fates differ between apicomplexan parasite lineages.

Gene content evolution

All apicomplexan species analyzed have small genomes compared to the free-living out-group. This result is consistent with comparative genomic analyses conducted in other pathogenic bacteria and eukaryotes; extreme genome reduction is a common theme in the genome evolution of these organisms [45].

A large proportion of the genes in apicomplexans are genus-specific (Figure 2). One parsimonious explanation for this observation is that each lineage acquired a new set of genes during its evolutionary history. An alternative explanation invokes differential loss among lineages when evolving from a free-living ancestor with a relatively large genome. We found that 23% of the protein coding genes in P. falciparum and 16% in T. annulata have a complex phylogenetic distribution pattern and do not fit into a simple single gain/loss model. These results suggest that some ancestral genes in the apicomplexans may have experienced multiple independent losses during their evolutionary history. Further investigation is necessary to distinguish true gene gains from differential retention of ancestral genes.

Comparison of genes with different levels of lineage specificity

Consistent with previous studies in bacteria [13], fungi [3], and animals [11, 12, 14], we observed a pattern in which sequence divergence is higher in genes with a higher level of lineage specificity. One explanation is that phylogenetically conserved genes are often involved in fundamental cellular processes (see Results). These genes are likely to be under purifying selection that constrains the rate of sequence divergence. In support of this hypothesis, we observe that the mean d N /d S ratio among the level 1 genes in Theileria is only 0.07 (Table 2), indicating an extremely low rate of nonsynonymous substitution relative to synonymous substitution.

Based on the hypothesis that lineage-specific genes are often involved in adaptation [4], such as invasion of hosts or evasion of the immune responses, lineage-specific genes may be under positive selection and have a faster rate of sequence divergence. Our data is suggestive in this regard, as genus-specific genes exhibit higher sequence divergence than genes with lower levels of lineage specificity. Unfortunately we cannot directly test the hypothesis that lineage-specific genes are more likely to be under positive selection using the d N /d S ratio data. The level of sequence divergence is too high in both species pairs for such analysis. Practically all of the genes from the Plasmodium pair and approximately 1,000 genes from the Theileria pair (i.e., more than a quarter of the gene repertoire) have a d S estimate that is larger than one. Under this high level of sequence divergence, we cannot confidently estimate the substitution rate due to saturation. Better detection of positive selection in these genes requires data on genetic variation at within- and between-species levels [46, 47].

Codon bias analyses indicate that species-specific genes have a different codon preference compared to other genes in the same genome, whereas the genes with lower levels of lineage specificity are relatively similar to each other (Table 3). It is possible that species-specific genes are relatively young and have yet to adapt to the codon usage pattern of the genome. Support for this hypothesis provided by the observation that the (G + C) content at the third codon position is much lower in the phylogenetically conserved genes in P. falciparum (Figure 4), suggesting that these 'older' genes are more biased toward GC-poor codons in this AT-rich genome. Alternatively, some species-specific genes may be subject to a different pattern of selection and thus possess different codon preference.

For the lineage-specific genes at the genus and species level that have functional annotations, many are known surface antigens. Because surface antigens are used by the parasites to interact with their hosts [48], such as adhesion to the cell surface or evasion of the host immune response, this result supports the hypothesis that (at least some) lineage-specific genes are involved in host-parasite interactions and have facilitated lineage-specific adaptation. Interestingly, surface antigens are species-specific in Plasmodium, but are genus-specific in Theileria. In addition, 62% of P. falciparum-specific genes contain a putative signal peptide or at least one predicted transmembrane domain. This result is consistent with one previous study that compared P. falciparum with three other Plasmodium species that cause rodent malaria [49]. Of the 168 P. falciparum-specific genes identified in this previous study that are not located in sub-telomeric regions, 68% are predicted to be exported to the surface of the parasites or the infected host cells.

Comparison between Plasmodium and Theileria

Previous studies suggest that the two focal species pairs have similar divergence times. The two Plasmodium species diverged about 80–100 million years ago [41] and the two Theileria species diverged about 82 million years ago [42]. Our results indicate that sequence divergence is much higher between the two Plasmodium species (Figures 1 and 3). This may be caused by the difference in nucleotide composition, since P. falciparum has a GC content of 24% while P. vivax has a GC content of 46% in the coding region. Bias in nucleotide composition has been shown to change codon usage and amino acid composition [50]. Alternatively, it is also possible that the divergence time between T. annulata and T. parva was overestimated because it was based on a simplified assumption that the synonymous substitution rate in Theileria is similar to that in Plasmodium [42].

In both P. falciparum and T. annulata, the sub-telomeric regions contain exclusively genus- or species-specific genes. Interestingly, the physical size of these regions is not correlated with chromosome size. This observation indicates that these regions are proportionally larger in smaller chromosomes and helps explains the pattern that the three small chromosomes in P. falciparum have many more species-specific genes than predicted by random expectations (see Results). In addition, genes that are located near a chromosome end have a higher level of sequence divergence in both species, regardless of their lineage specificity (Figure 8). The high evolutionary rates in sub-telomeric regions are shared by many eukaryotic lineages; high rates of inter-chromosomal recombination, local duplication, and segmental rearrangement have been reported in organisms including humans [51], yeasts [52], and plants [53].

Given the high rates of evolution in sub-telomeric regions, it may be advantageous for pathogens to have their surface antigen genes located in these evolutionary hotspots to facilitate the generation of antigenic diversity. Consistent with this hypothesis, many micro-parasites have large gene families that encode surface antigens in sub-telomeric regions (reviewed in [54]). The best-studied example is the causative agent of African trypanosomiasis, Trypanosoma brucei. The vsg gene family in T. brucei encodes variant surface glycoproteins (VSG) that form a dense coat on the outside of the parasite. In the bloodstream stage, T. brucei sequentially expresses different members of the vsg gene family, one at a time, to generate antigenic variation [55]. The positioning of vsg genes in the genome is tightly linked to regulation of expression; the actively expressed vsg is duplicated into one of the bloodstream expression sites located in the sub-telomeric regions (reviewed in [56, 57]). This homologous recombination process which involves loci that are not positional alleles is hypothesized to be important in generating genetic diversity within the gene family [54]. Although the genes encoding surface antigens in P. falciparum are not known to be duplicated into specific expression sites as observed in T. brucei, the clustering of these genes in sub-telomeric regions can facilitate inter-chromosomal recombination that increases antigenic variation [58].

We found that most of the surface antigen genes in P. falciparum are located in sub-telomeric regions, as previously noted [28]. Several studies have established the importance of genome location in the generation and maintenance of antigenic variation in P. falciparum [58, 59]. The surface antigen PfEMP1 possessed by P. falciparum is exported to the cell surface of infected erythrocytes. PfEMP1 can remove infected erythrocytes from blood circulation by cellular adherence to microvascular endothelial cells and avoid spleen-dependent killing [60]. The study on genetic structuring suggested that the approximately 60 copies of var genes (which encode PfEMP1) in the P. falciparum genome can be divided into three functionally diverged groups with two in sub-telomeric regions and one close to the centers of chromosomes [59]. Furthermore, the recombination rate is found to be high among members in the same functional group but low for members belonging to different groups. This recombinational hierarchy may facilitate the generation of genetic diversity within a group and promote specialization between different groups. Experimental evidence suggests that the clustering of var genes in the sub-telomeric regions is important in the epigenetic regulation of gene expression in P. falciparum [61, 62].

Given the generality of association between surface antigen genes and sub-telomeric regions in micro-parasites, it is interesting to see that T. annulata appears to be an exception to this rule. This finding may provide an explanation for the difference in host range between the two apicomplexan lineages. Because a large percentage of surface antigen genes in Plasmodium are located in sub-telomeric regions, the generation of antigenic variation may be faster in Plasmodium than in Theileria. Our results indicate that gene families encoding surface antigens in Plasmodium are highly diverged between species within the genus, whereas the two Theileria species still share most of their surface antigens and the genes encoding them are distributed across the entire lengths of chromosomes. For this reason, Plasmodium may be able to adapt to new host species at a faster rate, resulting in its much wider host range compared to Theileria; Plasmodium spp. can infect mammals, birds, and reptiles, whereas Theileria spp. are limited to ruminants [34].

Conclusion

Our results agree with previous observations in other organisms that lineage-specific genes have a higher level of sequence divergence compared to phylogenetically conserved genes. In addition, two major apicomplexan lineages may have different mechanisms for generating or retaining species-specific genes. Because many lineage-specific genes in these parasites are surface antigens that interact with the host, future investigations on genome evolution in these parasites may facilitate the identification of new therapeutic or vaccine targets. Future studies that focus on improving functional annotation of parasite genomes and the collection of genetic variation data at different phylogenetic levels will be important in our understanding of parasite adaptation and natural selection.

Methods

Data source and orthologous gene identification

The data sources of the annotated proteins are listed in Table 1. Protein domain identification was performed with HMMPFAM [63] (version 20.0). Transmembrane domain prediction [28] and gene expression data [26] of annotated Plasmodium falciparum genes were downloaded from PlasmoDB [64] (Release 5.3).

Orthologous gene clusters were identified using OrthoMCL [39] (version 1.3, April 10, 2006) with default parameter settings. The ortholog identification process in OrthoMCL is largely based on the popular criterion of reciprocal best-hits but also involves an additional step of Markov Clustering [40] to improve sensitivity and specificity. We used WU-BLAST [65] (version 2.0) for the all-against-all BLASTP similarity search step with the e-value cutoff set to 1e-15.

Phylogenetic inference

Based on the orthologous gene clustering result, we identified genes that are shared by all nine species to infer the species tree. Orthologous gene clusters that contain more than one gene from any given species were removed to avoid the complications introduced by paralogous genes in phylogenetic inference. Of the 768 orthologous gene clusters that are shared by all nine species (Figure 2), 154 clusters were single-copy in all species. For each gene, CLUSTALW [66] (version 1.83) was used for multiple sequence alignment. We enabled the 'tossgaps' option to ignore gaps when constructing the guide tree and used the default settings for all other parameters. The alignments produced by CLUSTALW were filtered by GBLOCKS [67] (version 0.91b) to remove regions that contain gaps or are highly divergent. Individual genes that had less than 100 aligned amino acid sites (33/154) or contained identical sequences from different taxa (38/154) after GBLOCKS filtering were eliminated from further analysis. We concatenated the alignments from the remaining 83 genes (with a total of 24,494 aligned amino acid sites) and utilized PHYML [68] to infer the species tree based on the maximum likelihood method. We used PHYML to estimate the proportion of invariable sites and the gamma distribution parameter (with eight substitution categories). The substitution model was set to JTT [69] and we enabled the optimization options for tree topology, branch lengths, and rate parameters. To estimate the level of support on each internal branch, we performed 100 non-parametric bootstrap samplings.

Quantification of sequence divergence

The nonsynonymous and synonymous substitution rates at the nucleotide level (i.e., d N and d S ) were estimated using CODEML in the PAML package [70]. We performed pairwise sequence alignment at the amino acid level using CLUSTALW [66] with default parameters for all orthologous genes that are single copy in both Plasmodium species or both Theileria species. The protein alignments were converted into the corresponding nucleotide alignments using NAL2PAL [71] (version 12). All gap positions were removed from the alignments before the substitution rate estimation by CODEML. To avoid problems of inaccurate rate estimation caused by saturation, we excluded sequences with a synonymous substitution rate (d S ) that is greater than one.

To quantify the level of sequence divergence at the amino acid level, we used TREE-PUZZLE [43] to calculate the protein distance between orthologs in sister species. The parameters were set to the JTT substitution model [69], mixed model of rate heterogeneity with one invariable and eight Gamma rate categories, and the exact and slow parameter estimation. Orthologous sequences were first aligned using CLUSTALW [66] followed by a filtering step using GBLOCKS [67] to remove gaps and highly divergent regions before the calculation of protein distance. Five sequences (PFA0650w, PFD0105c, PFL0060w, and PFD1140w from P. falciparum and TA18345 from T. annulata) that were not reliably aligned to their ortholog in the sister species were excluded from this analysis.

Calculation of relative codon bias

The relative codon bias between sets of genes in the two focal species, P. falciparum and T. annulata, was calculated based on the method developed by Karlin et al. [44]. Briefly, the method considers two sets of genes, one focal set and one reference set, and calculates the difference in relative frequency of codon family that encode the same amino acid between the two sets. The theoretical maximum of the difference between two sets of genes is 2.000, but the empirical values based on biological data generally range from 0.050 to 0.300 [44, 72, 73]. This measurement is different from the conventional codon adaptation index (CAI) developed by Sharp and Li [74], in which a set of highly expressed genes is always used as the reference set. We choose the relative codon bias to measure codon preference because it can provide a better resolution under certain conditions. For example, two sets of weakly expressed genes may have similar values of codon adaptation index but still possess vastly different codon preferences.

Visualization and quantification of chromosomal location

GBROWSE [75] was used for visualization of gene distribution on chromosomes. To quantify the pattern of chromosomal location, we calculated the distance of each gene to the nearest chromosome end. For example, the P. falciparum gene PF10_0023 on chromosome MAL10 (physical size is 1,694,445 bp) starts at position 99,380 and ends at 100,362. Its distance to the nearest chromosome end was calculated as 99,380 - 1 = 99,379 bp. For gene PF10_0369 on the same chromosome that starts at 1,493,991 and ends at 1,496,955, its distance to the nearest chromosome end was calculated as 1,694,445 – 1,496,955 = 197,490 bp. The orientation of a gene (i.e., whether it is on the '+' strand or the '-' strand) is ignored for distance calculation.

References

Rubin GM, Yandell MD, Wortman JR, Gabor Miklos GL, Nelson CR, Hariharan IK, Fortini ME, Li PW, Apweiler R, Fleischmann W, Cherry JM, Henikoff S, Skupski MP, Misra S, Ashburner M, Birney E, Boguski MS, Brody T, Brokstein P, Celniker SE, Chervitz SA, Coates D, Cravchik A, Gabrielian A, Galle RF, Gelbart WM, George RA, Goldstein LSB, Gong F, Guan P, et al: Comparative Genomics of the Eukaryotes. Science. 2000, 287: 2204-2215. 10.1126/science.287.5461.2204.

Fischer D, Eisenberg D: Finding families for genomic ORFans. Bioinformatics. 1999, 15: 759-762. 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.9.759.

Cai J, Woo P, Lau S, Smith D, Yuen K-y: Accelerated evolutionary rate may be responsible for the emergence of lineage-specific genes in Ascomycota. J Mol Evol. 2006, 63: 1-11. 10.1007/s00239-004-0372-5.

Wilson GA, Bertrand N, Patel Y, Hughes JB, Feil EJ, Field D: Orphans as taxonomically restricted and ecologically important genes. Microbiology. 2005, 151: 2499-2501. 10.1099/mic.0.28146-0.

Striepen B, Pruijssers AJP, Huang JL, Li C, Gubbels MJ, Umejiego NN, Hedstrom L, Kissinger JC: Gene transfer in the evolution of parasite nucleotide biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004, 101: 3154-3159. 10.1073/pnas.0304686101.

Gogarten JP, Townsend JP: Horizontal gene transfer, genome innovation and evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005, 3: 679-687. 10.1038/nrmicro1204.

Ochman H, Lawrence JG, Groisman EA: Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation. Nature. 2000, 405: 299-304. 10.1038/35012500.

Lerat E, Daubin V, Ochman H, Moran NA: Evolutionary origins of genomic repertoires in bacteria. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3: e130-10.1371/journal.pbio.0030130.

Huang JL, Mullapudi N, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Kissinger JC: A first glimpse into the pattern and scale of gene transfer in the Apicomplexa. Int J Parasitol. 2004, 34: 265-274. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.11.025.

Hotopp JCD, Clark ME, Oliveira DCSG, Foster JM, Fischer P, Torres MCM, Giebel JD, Kumar N, Ishmael N, Wang S, Ingram J, Nene RV, Shepard J, Tomkins J, Richards S, Spiro DJ, Ghedin E, Slatko BE, Tettelin H, Werren JH: Widespread lateral gene transfer from intracellular bacteria to multicellular eukaryotes. Science. 2007, 317: 1753-1756. 10.1126/science.1142490.

Domazet-Loso T, Tautz D: An evolutionary analysis of orphan genes in Drosophila. Genome Res. 2003, 13: 2213-2219. 10.1101/gr.1311003.

Alba MM, Castresana J: Inverse relationship between evolutionary rate and age of mammalian genes. Mol Biol Evol. 2005, 22: 598-606. 10.1093/molbev/msi045.

Daubin V, Ochman H: Bacterial genomes as new gene homes: the genealogy of ORFans in E. coli. Genome Res. 2004, 14: 1036-1042. 10.1101/gr.2231904.

Wang W, Zheng H, Yang S, Yu H, Li J, Jiang H, Su J, Yang L, Zhang J, McDermott J, Samudrala R, Wang J, Yang H, Yu J, Kristiansen K, Wong GK: Origin and evolution of new exons in rodents. Genome Res. 2005, 15: 1258-1264. 10.1101/gr.3929705.

Kellis M, Birren BW, Lander ES: Proof and evolutionary analysis of ancient genome duplication in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2004, 428: 617-624. 10.1038/nature02424.

Elhaik E, Sabath N, Graur D: The "Inverse relationship between evolutionary rate and age of mammalian genes" is an artifact of increased genetic distance with rate of evolution and time of divergence. Mol Biol Evol. 2006, 23: 1-3. 10.1093/molbev/msj006.

Alba MM, Castresana J: On homology searches by protein Blast and the characterization of the age of genes. BMC Evol Biol. 2007, 7: 53-10.1186/1471-2148-7-53.

Levine MT, Jones CD, Kern AD, Lindfors HA, Begun DJ: Novel genes derived from noncoding DNA in Drosophila melanogaster are frequently X-linked and exhibit testis-biased expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006, 103: 9935-9939. 10.1073/pnas.0509809103.

Chen S-T, Cheng H-C, Barbash DA, Yang H-P: Evolution of hydra, a recently evolved testis-expressed gene with nine alternative first exons in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3: e107-10.1371/journal.pgen.0030107.

Patthy L: Genome evolution and the evolution of exon-shuffling – a review. Gene. 1999, 238: 103-114. 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00228-0.

Moran JV, DeBerardinis RJ, Kazazian HH: Exon shuffling by L1 retrotransposition. Science. 1999, 283: 1530-1534. 10.1126/science.283.5407.1530.

Blomme T, Vandepoele K, De Bodt S, Simillion C, Maere S, Van de Peer Y: The gain and loss of genes during 600 million years of vertebrate evolution. Genome Biol. 2006, 7: R43-10.1186/gb-2006-7-5-r43.

Schmid KJ, Aquadro CF: The evolutionary analysis of "orphans" from the Drosophila genome identifies rapidly diverging and incorrectly annotated genes. Genetics. 2001, 159: 589-598.

Ochman H: Distinguishing the ORFs from the ELFs: short bacterial genes and the annotation of genomes. Trends Genet. 2002, 18: 335-337. 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02668-9.

Rosenow C, Saxena RM, Durst M, Gingeras TR: Prokaryotic RNA preparation methods useful for high density array analysis: comparison of two approaches. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29:

Le Roch KG, Zhou Y, Blair PL, Grainger M, Moch JK, Haynes JD, De la Vega P, Holder AA, Batalov S, Carucci DJ, Winzeler EA: Discovery of gene function by expression profiling of the malaria parasite life cycle. Science. 2003, 301: 1503-1508. 10.1126/science.1087025.

Nekrutenko A, Makova KD, Li W-H: The KA/KS ratio test for assessing the protein-coding potential of genomic regions: an empirical and simulation study. Genome Res. 2002, 12: 198-202. 10.1101/gr.200901.

Gardner MJ, Hall N, Fung E, White O, Berriman M, Hyman RW, Carlton JM, Pain A, Nelson KE, Bowman S, Paulsen IT, James K, Eisen JA, Rutherford K, Salzberg SL, Craig A, Kyes S, Chan MS, Nene V, Shallom SJ, Suh B, Peterson J, Angiuoli S, Pertea M, Allen J, Selengut J, Haft D, Mather MW, Vaidya AB, Martin DMA, et al: Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum . Nature. 2002, 419: 498-511. 10.1038/nature01097.

Abrahamsen MS, Templeton TJ, Enomoto S, Abrahante JE, Zhu G, Lancto CA, Deng M, Liu C, Widmer G, Tzipori S, Buck GA, Xu P, Bankier AT, Dear PH, Konfortov BA, Spriggs HF, Iyer L, Anantharaman V, Aravind L, Kapur V: Complete genome sequence of the Apicomplexan, Cryptosporidium parvum . Science. 2004, 304: 441-445. 10.1126/science.1094786.

Xu P, Widmer G, Wang Y, Ozaki LS, Alves JM, Serrano MG, Puiu D, Manque P, Akiyoshi D, Mackey AJ, Pearson WR, Dear PH, Bankier AT, Peterson DL, Abrahamsen MS, Kapur V, Tzipori S, Buck GA: The genome of Cryptosporidium hominis. Nature. 2004, 431: 1107-1112. 10.1038/nature02977.

Pain A, Renauld H, Berriman M, Murphy L, Yeats CA, Weir W, Kerhornou A, Aslett M, Bishop R, Bouchier C, Cochet M, Coulson RMR, Cronin A, de Villiers EP, Fraser A, Fosker N, Gardner M, Goble A, Griffiths-Jones S, Harris DE, Katzer F, Larke N, Lord A, Maser P, McKellar S, Mooney P, Morton F, Nene V, O'Neil S, Price C, et al: Genome of the host-cell transforming parasite Theileria annulata compared with T. parva. Science. 2005, 309: 131-133. 10.1126/science.1110418.

Gardner MJ, Bishop R, Shah T, de Villiers EP, Carlton JM, Hall N, Ren Q, Paulsen IT, Pain A, Berriman M, Wilson RJM, Sato S, Ralph SA, Mann DJ, Xiong Z, Shallom SJ, Weidman J, Jiang L, Lynn J, Weaver B, Shoaibi A, Domingo AR, Wasawo D, Crabtree J, Wortman JR, Haas B, Angiuoli SV, Creasy TH, Lu C, Suh B, et al: Genome sequence of Theileria parva, a bovine pathogen that transforms lymphocytes. Science. 2005, 309: 134-137. 10.1126/science.1110439.

Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O: Toxoplasmosis. Lancet. 2004, 363: 1965-1976. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16412-X.

Lee J, Leedale G, Bradbury P: An Illustrated Guide to the Protozoa. Edited by: Lawrence KS. 2000, USA: Society of Protozoologists, 2

Escalante A, Ayala F: Evolutionary origin of Plasmodium and other Apicomplexa based on rRNA genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995, 92: 5793-5797. 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5793.

Morrison DA, Ellis JT: Effects of nucleotide sequence alignment on phylogeny estimation: A case study of 18S rDNAs of Apicomplexa. Mol Biol Evol. 1997, 14: 428-441.

Douzery EJP, Snell EA, Bapteste E, Delsuc F, Philippe H: The timing of eukaryotic evolution: Does a relaxed molecular clock reconcile proteins and fossils?. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004, 101: 15386-15391. 10.1073/pnas.0403984101.

Philippe H, Snell EA, Bapteste E, Lopez P, Holland PWH, Casane D: Phylogenomics of eukaryotes: Impact of missing data on large alignments. Mol Biol Evol. 2004, 21: 1740-1752. 10.1093/molbev/msh182.

Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Roos DS: OrthoMCL: Identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 2003, 13: 2178-2189. 10.1101/gr.1224503.

Van Dongen S: Graph clustering by flow simulation. PhD thesis. 2000, University of Utrecht

Perkins SL, Schall JJ: A molecular phylogeny of malarial parasites recovered from cytochrome b gene sequences. J Parasitol. 2002, 88: 972-978.

Roy SW, Penny D: Large-scale intron conservation and order-of-magnitude variation in intron loss/gain rates in apicomplexan evolution. Genome Res. 2006, 16: 1270-1275. 10.1101/gr.5410606.

Schmidt HA, Strimmer K, Vingron M, von Haeseler A: TREE-PUZZLE: maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis using quartets and parallel computing. Bioinformatics. 2002, 18: 502-504. 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.502.

Karlin S, Mrazek J, Campbell AM: Codon usages in different gene classes of the Escherichia coli genome. Mol Microbiol. 1998, 29: 1341-1355. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01008.x.

Lawrence JG: Common themes in the genome strategies of pathogens. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005, 15: 584-588. 10.1016/j.gde.2005.09.007.

Kidgell C, Volkman SK, Daily J, Borevitz JO, Plouffe D, Zhou Y, Johnson JR, Le Roch KG, Sarr O, Ndir O, Mboup S, Batalov S, Wirth DF, Winzeler EA: A systematic map of genetic variation in Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Pathog. 2006, 2: e57-10.1371/journal.ppat.0020057.

Barry AE, Leliwa-Sytek A, Tavul L, Imrie H, Migot-Nabias F, Brown SM, McVean GAV, Day KP: Population genomics of the immune evasion (var) genes of Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Pathog. 2007, 3: e34-10.1371/journal.ppat.0030034.

Bull PC, Berriman M, Kyes S, Quail MA, Hall N, Kortok MM, Marsh K, Newbold CI: Plasmodium falciparum variant surface antigen expression patterns during malaria. PLoS Pathog. 2005, 1: e26-10.1371/journal.ppat.0010026.

Kooij TWA, Carlton JM, Bidwell SL, Hall N, Ramesar J, Janse CJ, Waters AP: A Plasmodium whole-genome synteny map: indels and synteny breakpoints as foci for species-specific genes. PLoS Pathog. 2005, 1: e44-10.1371/journal.ppat.0010044.

Foster P, Jermiin L, Hickey D: Nucleotide composition bias affects amino acid content in proteins coded by animal mitochondria. J Mol Evol. 1997, 44: 282-288. 10.1007/PL00006145.

Linardopoulou EV, Williams EM, Fan Y, Friedman C, Young JM, Trask BJ: Human subtelomeres are hot spots of interchromosomal recombination and segmental duplication. Nature. 2005, 437: 94-100. 10.1038/nature04029.

Ricchetti M, Dujon B, Fairhead C: Distance from the chromosome end determines the efficiency of double strand break repair in subtelomeres of haploid yeast. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2003, 328: 847-862. 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00315-2.

Kuo H-F, Olsen KM, Richards EJ: Natural variation in a subtelomeric region of Arabidopsis: implications for the genomic dynamics of a chromosome end. Genetics. 2006, 173: 401-417. 10.1534/genetics.105.055202.

Barry JD, Ginger ML, Burton P, McCulloch R: Why are parasite contingency genes often associated with telomeres?. Int J Parasitol. 2003, 33: 29-45. 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00247-3.

Cross GAM, Wirtz LE, Navarro M: Regulation of vsg expression site transcription and switching in Trypanosoma brucei. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 1998, 91: 77-91. 10.1016/S0166-6851(97)00186-2.

Navarro M, Penate X, Landeira D: Nuclear architecture underlying gene expression in Trypanosoma brucei. Trends Microbiol. 2007, 15: 263-270. 10.1016/j.tim.2007.04.004.

Dreesen O, Li B, Cross GAM: Telomere structure and function in trypanosomes: a proposal. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007, 5: 70-75. 10.1038/nrmicro1577.

Freitas-Junior LH, Bottius E, Pirrit LA, Deitsch KW, Scheidig C, Guinet F, Nehrbass U, Wellems TE, Scherf A: Frequent ectopic recombination of virulence factor genes in telomeric chromosome clusters of P. falciparum . Nature. 2000, 407: 1018-1022. 10.1038/35039531.

Kraemer SM, Smith JD: Evidence for the importance of genetic structuring to the structural and functional specialization of the Plasmodium falciparum var gene family. Mol Microbiol. 2003, 50: 1527-1538. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03814.x.

Baruch DI, Gormley JA, Ma C, Howard RJ, Pasloske BL: Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 is a parasitized erythrocyte receptor for adherence to CD36, thrombospondin, and intercellular adhesion molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996, 93: 3497-3502. 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3497.

Duraisingh MT, Voss TS, Marty AJ, Duffy MF, Good RT, Thompson JK, Freitas-Junior LH, Scherf A, Crabb BS, Cowman AF: Heterochromatin silencing and locus repositioning linked to regulation of virulence genes in Plasmodium falciparum . Cell. 2005, 121: 13-24. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.036.

Scherf A, Figueiredo LM, Freitas-Junior LH: Plasmodium telomeres: a pathogen's perspective. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2001, 4: 409-414. 10.1016/S1369-5274(00)00227-7.

Bateman A, Coin L, Durbin R, Finn RD, Hollich V, Griffiths-Jones S, Khanna A, Marshall M, Moxon S, Sonnhammer ELL, Studholme DJ, Yeats C, Eddy SR: The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32: D138-D141. 10.1093/nar/gkh121.

Bahl A, Brunk B, Crabtree J, Fraunholz MJ, Gajria B, Grant GR, Ginsburg H, Gupta D, Kissinger JC, Labo P, Li L, Mailman MD, Milgram AJ, Pearson DS, Roos DS, Schug J, Stoeckert CJ, Whetzel P: PlasmoDB: the Plasmodium genome resource. A database integrating experimental and computational data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31: 212-215. 10.1093/nar/gkg081.

WU-BLAST. [http://blast.wustl.edu/]

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ: CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, positions-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22: 4673-4680. 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673.

Castresana J: Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol. 2000, 17: 540-552.

Guindon S, Gascuel O: A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003, 52: 696-704. 10.1080/10635150390235520.

Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM: The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput Appl Biosci. 1992, 8: 275-282.

Yang Z: PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007, 24: 1586-1591. 10.1093/molbev/msm088.

Suyama M, Torrents D, Bork P: PAL2NAL: robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34: W609-612. 10.1093/nar/gkl315.

Karlin S, Mrazek J: Predicted highly expressed genes of diverse prokaryotic genomes. J Bacteriol. 2000, 182: 5238-5250. 10.1128/JB.182.18.5238-5250.2000.

Karlin S, Campbell AM, Mrazek J: Comparative DNA analysis across diverse genomes. Annu Rev Genet. 1998, 32: 185-225. 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.185.

Sharp PM, Li WH: The codon adaptation index – a measure of directional synonymous codon usage bias, and its potential applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987, 15: 1281-1295. 10.1093/nar/15.3.1281.

Stein LD, Mungall C, Shu S, Caudy M, Mangone M, Day A, Nickerson E, Stajich JE, Harris TW, Arva A, Lewis S: The generic genome browser: a building block for a model organism system database. Genome Res. 2002, 12: 1599-1610. 10.1101/gr.403602.

Heiges M, Wang HM, Robinson E, Aurrecoechea C, Gao X, Kaluskar N, Rhodes P, Wang S, He CZ, Su YQ, Miller J, Kraemer E, Kissinger JC: CryptoDB: a Cryptosporidium bioinformatics resource update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34: D419-D422. 10.1093/nar/gkj078.

Hertz-Fowler C, Peacock CS, Wood V, Aslett M, Kerhornou A, Mooney P, Tivey A, Berriman M, Hall N, Rutherford K, Parkhill J, Ivens AC, Rajandream M-A, Barrell B: GeneDB: a resource for prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32: D339-343. 10.1093/nar/gkh007.

J Craig Venter Institute. [http://jcvi.org/]

Gajria B, Bahl A, Brestelli J, Dommer J, Fischer S, Gao X, Heiges M, Iodice J, Kissinger JC, Mackey AJ, Pinney DF, Roos DS, Stoeckert CJ, Wang H, Brunk BP: ToxoDB: an integrated Toxoplasma gondii database resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, gkm981-

Aury J-M, Jaillon O, Duret L, Noel B, Jubin C, Porcel BM, Segurens B, Daubin V, Anthouard V, Aiach N, Arnaiz O, Billaut A, Beisson J, Blanc I, Bouhouche K, Camara F, Duharcourt S, Guigo R, Gogendeau D, Katinka M, Keller A-M, Kissmehl R, Klotz C, Koll F, Le Mouel A, Lepere G, Malinsky S, Nowacki M, Nowak JK, Plattner H, et al: Global trends of whole-genome duplications revealed by the ciliate Paramecium tetraurelia. Nature. 2006, 444: 171-178. 10.1038/nature05230.

Arnaiz O, Cain S, Cohen J, Sperling L: ParameciumDB: a community resource that integrates the Paramecium tetraurelia genome sequence with genetic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35: D439-444. 10.1093/nar/gkl777.

Eisen JA, Coyne RS, Wu M, Wu DY, Thiagarajan M, Wortman JR, Badger JH, Ren QH, Amedeo P, Jones KM, Tallon LJ, Delcher AL, Salzberg SL, Silva JC, Haas BJ, Majoros WH, Farzad M, Carlton JM, Smith RK, Garg J, Pearlman RE, Karrer KM, Sun L, Manning G, Elde NC, Turkewitz AP, Asai DJ, Wilkes DE, Wang YF, Cai H, et al: Macronuclear genome sequence of the ciliate Tetrahymena thermophila, a model eukaryote. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4: 1620-1642. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040286.

Acknowledgements

CHK was supported by a NIH Training Grant (GM07103), the Kirby and Jan Alton Graduate Fellowship, and a Dissertation Completion Assistantship at the University of Georgia. Funding for this work was provided by NIH R01 AI068908 to JCK. The Institute of Bioinformatics and the Research Computing Center at the University of Georgia provided computation resources. P. Brunk, F. Chen, J. Felsenstein, M. Heiges, J. Mrazek, A. Oliveira, E. Robinson, and H. Wang provided valuable assistance on the use of computer hardware and software. D. Promislow, J. Bennetzen, D. Hall, J. Linder, J. Moorad, B. Striepen, and four anonymous reviewers provided helpful comments that improved the manuscript. We thank the J. Craig Venter Institute for providing pre-publication access to the genome sequence data of Plasmodium vivax and Toxoplasma gondii. The US Department of Defense, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund provided funding for the genome sequencing project of Plasmodium vivax and Toxoplasma gondii.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

CHK developed the concept of this study, performed the analysis, and wrote the manuscript. JCK provided supervision, feedback, and comments on the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12862_2007_677_MOESM1_ESM.xls

Additional file 1: Genes used to infer the species tree. List of the 83 single-copy genes used to infer the species tree. Gene ID and description are based on the Plasmodium falciparum sequence annotation in each ortholog group. (XLS 46 KB)

12862_2007_677_MOESM2_ESM.xls

Additional file 2: Lists of lineage-specific genes in Plasmodium falciparum. Lists of lineage-specific genes, grouped by the level of lineage specificity defined in Figure 2. (XLS 855 KB)

12862_2007_677_MOESM3_ESM.xls

Additional file 3: Lists of lineage-specific genes in Theileria annulata. Lists of lineage-specific genes, grouped by the level of lineage specificity defined in Figure 2. (XLS 616 KB)

12862_2007_677_MOESM4_ESM.pdf

Additional file 4: Chromosomal location of lineage-specific genes in Plasmodium falciparum. Graphical distribution of genes on all 14 Plasmodium falciparum chromosomes. (PDF 310 KB)

12862_2007_677_MOESM5_ESM.pdf

Additional file 5: Chromosomal location of lineage-specific genes in Theileria annulata. Graphical distribution of genes on all 4 Theileria annulata chromosomes. (PDF 144 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuo, CH., Kissinger, J.C. Consistent and contrasting properties of lineage-specific genes in the apicomplexan parasites Plasmodium and Theileria. BMC Evol Biol 8, 108 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-8-108

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-8-108