Abstract

Background

Marine pelagic fishes exhibit rather complex patterns of genetic differentiation, which are the result of both historical processes and present day gene flow. Comparative multi-locus analyses based on both nuclear and mitochondrial genetic markers are probably the most efficient and informative approach to discerning the relative role of historical events and life-history traits in shaping genetic heterogeneity. The European sardine (Sardina pilchardus) is a small pelagic fish with a relatively high migratory capability that is expected to show low levels of genetic differentiation among populations. Previous genetic studies based on meristic and mitochondrial control region haplotype frequency data supported the existence of two sardine subspecies (S. p. pilchardus and S. p. sardina).

Results

We investigated genetic structure of sardine among nine locations in the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea using allelic size variation of eight specific microsatellite loci. Bayesian clustering and assignment tests, maximum likelihood estimates of migration rates, as well as classical genetic-variance-based methods (hierarchical AMOVA test and R ST pairwise comparisons) supported a single evolutionary unit for sardines. These analyses only detected weak but significant genetic differentiation, which followed an isolation-by-distance pattern according to Mantel test.

Conclusion

We suggest that the discordant genetic structuring patterns inferred based on mitochondrial and microsatellite data might indicate that the two different classes of molecular markers may be reflecting different and complementary aspects of the evolutionary history of sardine. Mitochondrial data might be reflecting past isolation of sardine populations into two distinct groupings during Pleistocene whereas microsatellite data reveal the existence of present day gene flow among populations, and a pattern of isolation by distance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Understanding the rather complex population structure and dynamics of marine pelagic fishes requires discerning the relative influence of life-history traits and historical processes in shaping present-day population patterns (e.g. [1–7]). Marine pelagic fishes exhibit great dispersal capability that enhances gene flow, as well as large effective population sizes that impose limitations to genetic drift (e.g. [8–11]). The combination of both life-history traits acts as major homogenizing force, which hampers genetic differentiation, and ultimately may lead to panmixia (e.g. [2, 12, 13]). In contrast, other life-history traits such as phylopatric behavior or local larval retention and recruitment act promoting isolation by distance, and local adaptations that eventually render low but significant levels of genetic differentiation in marine pelagic fish populations (e.g. [2, 10, 14]). Moreover, population structuring and dynamics of marine fishes are also heavily influenced by the physical peculiarities of the marine environment, where connectivity, and thus dispersal, is greatly dependant on ocean fronts and currents, as well as on bathymetry. For instance, the Agulhas current [15] seems to promote migration of bigeye tuna across the Cape of Good Hope from the Indian Ocean into the Atlantic Ocean (e.g. [9, 16, 17]) whereas the Almeria-Oran front [18] acts as a major barrier to gene flow between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean for some species such as e.g. the mackerel [2], the anchovy [3] or the swordfish [7]. In addition, historical factors including past changes in the direction and sense of ocean currents, vicariant events caused by both climatic and eustatic sea level changes [7, 9, 19], as well as climate-associated periodical extinctions and recolonizations [20] have also decisively contributed to shaping present-day population genetic differentiation and geographic distribution.

Comparative analyses of both nuclear and mitochondrial genetic markers offer the best and most powerful approach to characterizing population genetic structure and diagnosing the evolutionary processes responsible for genetic differentiation in marine pelagic fishes (e.g. [6, 17, 21]). Therefore, genetic studies including both types of molecular markers are largely wanting.

The European sardine (Sardina pilchardus, Walbaum 1792) is a small pelagic fish that inhabits the coasts of the eastern North Atlantic Ocean (from the North Sea to Senegal), as well as the Mediterranean Sea, the Sea of Marmara, and the Black Sea [22, 23]. Adults usually swim close to the littoral zone, and display daily vertical movement capacity [23, 24]. Spawning occurs in open waters and larvae remain in plankton for long periods of time [24]. In spite of the relatively great dispersal capability of sardines both at the larval and adult stages, tagging and egg production data suggest that total inter annual displacement may be restricted by changes in the ocean water temperature and productivity, as well as by hydrogeographic boundaries [24–26]. Based on these life-history traits, sardine populations in close geographic proximity are expected to show modest genetic differentiation. That is the case in the Aegean Sea [27], the Spanish Mediterranean coast [28], and the Adriatic Sea [29]. At a larger scale, isolation by distance, and the existence of potential past or present-day barriers may promote higher levels of genetic differentiation.

Morphological studies based on gill raker counts and head length [22, 30] found enough phenotypic variation to differentiate two subspecies, S. p. pilchardus (Eastern Atlantic Ocean, from the North Sea to Southern Portugal) and S. p. sardina (Mediterranean Sea and Northwest African coast). Although no private mitochondrial control region sequence haplotype could be found for each proposed subspecies, they were suggested to be genetically distinct based on significant pairwise haplotype frequency differences [31]. Moreover, some subspecies pairwise comparisons involving locations around the Atlantic Ocean region off the Gibraltar Strait showed no significant haplotype frequency differences, which suggested that this area could be a contact zone of both subspecies [31]. According to mitochondrial evidence, the well-known Almeria-Oran oceanographic front [18] between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea is not a phylogenetic break for sardines.

The sardine is heavily fished all over its distribution with global catches of 1.600,000 tons per year (Fishery statistics 2003,[32]). In particular, Spain and Morocco are the countries with the largest captures (representing about the 77% of the total annual catch of sardines), and collapse of a sardine stock was reported off the Safi coast (Morocco) during the 1970s [33, 34]. Population genetic and historical demographic analyses of sardines from Safi based on mitochondrial sequence data showed strong genetic differentiation of this population sample, and the signature of an early genetic bottleneck. The genetic singularity of the sardines at Safi (also detected with allozyme data [35]), could have enhanced the effects of the historical collapse of the sardine stock [31].

In this study, we analyzed allele size variation of eight polymorphic microsatellite loci in Atlantic and Mediterranean sardines. We used coalescent-based approaches for the estimation of the actual number of populations, and employed hierarchical AMOVA and isolation by distance tests to study population genetic differentiation. Our main objective was to explore whether microsatellites provide concordant genetic differentiation patterns with respect to mitochondrial control region sequence data [31]. Comparative analysis of mitochondrial and nuclear multilocus data were used to further understand the historical and contemporary (i.e. life-history) components of sardine population structure. In addition, we tested whether the genetic singularity of the Safi population sample could be confirmed with nuclear data, and whether any signature of a genetic bottleneck was detected in this or other population samples.

Results

Microsatellite diversity among loci

Microsatellite polymorphism levels were high at the eight genotyped loci with 41 to 94 alleles per locus (mean NA value ± standard deviation was 60 ± 18.60), and mean observed and expected heterozygosities of HO = 0.738 ± 0.13 and HE = 0.748 ± 0.14, respectively (Table 1). The inbreeding coefficient varied between 0.003 at locus SAR2F and 0.450 at locus SAR1.12 (mean FIS = 0.202 ± 0.18), and only two loci (SAR2.18 and SARA2F) were in Hardy-Weinberg (HW) equilibrium over all population samples (Table 1). Tests for linkage disequilibrium showed a very low (3.6%) number of significant pairwise comparisons, which suggests independence of all examined loci.

Genetic diversity among sardine population samples and between subspecies

The amount of genetic variability was homogeneous among sardine population samples as indicated by the low standard deviations associated to the estimated mean number of alleles (NA = 29.3 ± 1.4), by mean allelic richness after rarefaction (NS = 27.3 ± 0.95), and by mean observed (HO = 0.747 ± 0.04) and expected (HE = 0.948 ± 0.00) heterozygosities (Table 1). The overall proportion of private alleles for the analyzed population samples was considerably high (32.1%). The inbreeding coefficient FIS within population samples across all loci was on average 0.224 ± 0.04. Sardine population samples at four locations (Larache, Quarteira, Pasajes, and Nador) showed significant mean FIS values, indicating significant departures from HW equilibrium due to homozygote excess (Table 1). A non-significant bimodal test indicated no evidence of unspecific locus amplification or genotyping errors, which could have resulted in null alleles. In addition, a null allele test based on expected homozygote and heterozygote allele size difference frequencies [36] detected that 55% of the pairwise comparisons presented HW disequilibrium mainly involving loci SAR193B, SAR19B5 and SARA3C (Additional file 1). We found that correcting for null allele frequencies [37] did not qualitatively affect the results (49% of the pairwise comparisons were still significant, data not shown). This suggests that putative null alleles had a very low effect on the average genetic diversity of our data, and hence the complete data set was included in further analyses.

The differences between S. p. pilchardus and S. p. sardina (as represented by Pasajes and the remaining population samples, respectively) genetic diversity measures were non-significant. The ANOVA test showed no differences for the mean number of alleles (NA) (F1,7 = 0.33, P = 0.58), the mean allelic richness after rarefaction (NS) (F1,7 = 0.85, P = 0.39), mean observed (HO) (F1,7 = 0.08, P = 0.78) and expected (HE) (F1,7 = 3.14, P = 0.12) heterozygosities, and the mean inbreeding coefficient (FIS) (F1,7 = 0.14, P = 0.71) between subspecies (Table 1).

Estimation of the number of possible populations and assignment of individuals

Bayesian clustering analyses [38] detected the highest likelihood for the model with K = 5. However, the modal value of ΔK was shown at K = 4 (Fig. 1). A Bayesian inference under a Dirichlet process prior [39, 40] estimated that the number of populations with the highest posterior probability was K = 3 (P = 1.0).

Number of sardine populations with the highest posterior probability expressed as the ΔK, for each of the nine assumed sardine populations (K). ΔK is calculated as the mean of the absolute values of the second derivative of L(K), (L" (K)) average over five runs divided by the standard deviation of L(K) [71].

The probability of assignment of individuals to the four or five possible populations as inferred using Bayesian clustering analyses [38] was generally low (P < 0.8). The Bayesian assignment test correctly assigned 20.1% of the individuals to their own source location (22.4 % being the proportion of individuals that could not be assigned to any of the reference populations).

Measures of genetic differentiation

The null hypothesis of no contribution of the Stepwise Mutation model (SMM; [41]) to genetic differentiation (ρRST = FST) was rejected (P < 0.000) based on the multilocus data set (Table 2), suggesting that RST should be preferred over FST for the calculation of genetic differentiation between sardine population samples [42]. Three out of eight loci showed significant differences in the allele permutation test (Table 2). The significant global RST test (0.024, P < 0.000, 95% C.I. 0.026 – 0.047) over all loci suggested population structuring in sardines. Of 36 pairwise comparisons, only nine comparisons involving Nador, Barcelona and Kavala locations revealed significant values after correction for multiple tests (Table 3). Interestingly, all pairwise comparisons between Pasajes (representing S. s. pilchardus) and the rest of the sampling sites (representing S. s. sardina) were non-significant.

The hierarchical AMOVA revealed overall significant genetic structuring of the analyzed samples (P < 0.00) (Table 4). A two gene pool structure separating the subspecies S. p. pilchardus (Pasajes sampling site) versus S. p. sardina samples was not significant (P = 0.44). A possible a priori hypothesis of geographic structuring (organized as Atlantic Ocean versus Mediterranean Sea samples) was also not supported by the AMOVA (P = 0.07) (Table 4). The Atlantic Ocean versus Mediterranean Sea comparison was repeated excluding the Pasajes population sample, which could mask small genetic differentiation. Potential geographic structuring between the two areas remained not significant (Table 4). According to the Mantel test, correlation between genetic distance determined as RST and geographical distance (log Km) was significant (correlation coefficient r = 0.51, R2 = 0.26, P < 0.009) (Fig. 2). The Mantel test correlating FST and geographic distances was not significant (not shown). Similarly, we found no significant correlation when using the Bayesian assignment DLR distances (correlation coefficient r = 0.09, R2 = 0.01, P = 0.59) (Fig. 2).

Genetic isolation by distance of all S. pilchardus population samples inferred from multilocus estimates of RST (solid circles) and DLR (solid squares) genetic distances versus geographical distance (Mantel test). Correlation coefficients: for RST r = 0.51, R2 = 0.26, P < 0.009; for DLR r = 0.09, R2 = 0.01, P = 0.59.

The Wilcoxon test detected recent bottlenecks in two population samples from the Mediterranean Sea corresponding to Nador and Kavala sampling sites (P two tails value of 0.031 for both tests), under the SMM model. No trace of genetic bottleneck was detected in Safi. Additionally, the test was performed using the Two Phase model (TPM; [43]) and the Infinite Allele model (IAM; [44]). In the first case, the test rendered non-significant results in all population samples. However Safi, Larache, Pasajes, Nador, and Kavala rendered significant results under the IAM.

Levels and patterns of gene flow among populations

The estimates of the population size parameter (Θ) ranged from 0.38 to 0.81 (0.51 ± 0.13) (Table 5) and were translated to an average effective population size (N e ) of 12,818 ± 325 sardine individuals (assuming a microsatellite mutation rate of 10-4 per locus per generation [45]). Migration rates between population samples were all of the same order, and no preferential directionality of the migrants was observed. The mixed model-nested ANOVA test showed no significant variation of the number of emigrants and immigrants between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea (F1,8 = 0.44, P = 0.53; F1,8 = 0.12, P = 0.74). Also the test rendered no significant variation of the number of emigrants among population samples (F1,8 = 0.00, P = 1.0). However a significant variation of immigrants among population samples (F1,8 = 3.14, P = 0.01) was detected. A one-way ANOVA was applied to test the null hypothesis of equal rate of immigrants between population samples. The analyses rendered a significant difference in the immigration rates among population samples (F1,8 = 3.67, P = 0.001), being Barcelona-Quarteira the only pairwise comparison that was significantly different (t > 1.998).

Discussion

The study of population genetic variation of marine pelagic fish species has proven to be particularly challenging because of the biological peculiarities of these fishes including large effective population sizes and high dispersal capacities, as well as because of the apparent lack of physical barriers to gene flow in the marine realm [6, 46–48]. Mitochondrial DNA is maternally inherited, lacks recombination, and shows relatively fast evolutionary rates, which make this molecular marker particularly suitable for inferring phylogeographic patterns [49]. This molecular marker is particularly appropriate for detecting historical vicariant or genetic bottleneck events, and has been very useful in describing present day phylogeography of taxa with relatively low dispersal capacity [49]. However, mitochondrial genetic variation is less helpful when tackling questions on present-day genetic structuring of taxa with large population sizes and high levels of gene flow within their distribution such as marine pelagic fishes (e.g. [6, 21]). Microsatellites are nuclear markers with higher mutation rates [50] that have proved to be more efficient and informative for detecting fine-scale population structure in marine pelagic fishes [17, 21, 51]. Overall, comparative analyses of nuclear and mitochondrial data should provide insights not achieved by each type of data separately, and should help in disentangling historical versus ecological factors involved in shaping contemporary population genetic structure of marine pelagic fishes [21].

Population genetic structure in sardines

The eight species-specific microsatellite loci used in this study showed high levels of polymorphism [52] and no significant linkage disequilibrium. All but two of the analyzed loci showed departures from HW equilibrium expectations due to homozygote excess. The null allele test [36] indicated that these departures could be due to the presence of null alleles, which seem to be rather common in large marine fish populations [53]. Nevertheless, since adjusting frequencies to take into account null alleles did not affect inbreeding coefficient estimates, all loci were used in the analyses.

Overall R ST detected weak but significant genetic structuring among sardine population samples. Pairwise estimates of R ST varied between 0.001 and 0.083, and were of the same level of magnitude to those reported for other marine fishes [53–56]. These relatively low R ST values could be attributed to high levels of size homoplasy, as expected when using polymorphic microsatellites with high mutation rates in species with large effective population sizes [53, 57, 58]. However, the observed relatively high number (32.1%) of private alleles, and their even distribution among population samples indicate that allele sharing between sardines at the different locations is rather limited and thus, that the effects of size homoplasy are minimal. Alternatively, it is more likely that the high levels of locus polymorphism are the ones responsible of only detecting weak genetic structuring [53, 58].

The difficulty in detecting genetic structuring is further evidenced by Bayesian clustering and assignment tests, as well as by hierarchical AMOVA and migration rate analyses. Although the different assayed Bayesian clustering analyses agree in rejecting the null hypothesis of panmixia, they failed to predict the exact number of inferred populations, which ranges from 3 to 5. Furthermore, assignment of individuals to the inferred populations was poor regardless of the method used. In addition, none of the tested a priori hypotheses of genetic structuring rendered significant results in the AMOVA. Maximum likelihood estimates of migration rates showed that gene flow among population samples is high and even. All these results together support that sardine population samples are acting as a single significant evolutionary unit. The Mantel test detected positive and significant correlation between genetic differentiation (only when using RST) and geographical distance suggesting that a model of isolation by distance could explain the subtle genetic structuring of sardines within the evolutionary unit. Isolation by distance seems to be a rather common pattern in small-medium pelagic marine fishes (e.g. [2, 19, 51]). It is important to note here that temporal replicates at the studied locations are needed to test whether the observed population genetic patterns are stable over time.

Relative effects of life-history traits and historical factors on genetic differentiation in sardines

All significant R ST pairwise comparisons involved Mediterranean Sea versus Central Atlantic Ocean population samples. Theses results could reflect the existence of a phylogeographic discontinuity between the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea, around the Gibraltar Strait and the Almeria-Oran front, as it has been postulated previously for different marine pelagic fish species (e.g. [2, 3, 7]). However, this hypothesis was rejected for sardines at the nuclear level because the hierarchical AMOVA failed to detect significant geographical structuring between the Atlantic and the Mediterranean sardine population samples, and high and even migration rates were observed between both basins. These results are congruent with those derived from population genetic analyses based on mitochondrial control region sequence data that also failed to find a barrier to gene flow for sardines at the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea [31]. The inferred genetic pattern for sardine is in agreement with the present-day gene flow exhibited by other marine pelagic fish species such as e.g. Scomber japonicus [2] or Thunnus thynnus [7] through the Atlantic-Mediterranean transition. The fact that the Gibraltar Strait and the Almeria-Oran front may or not act as barrier to gene flow for different marine pelagic species has been attributed to differences in life-history traits (e.g. dispersal capacity [2]) and for other marine fish species due to the existence of distinct past demographical events (e.g. bottlenecks [7]). More comparative studies on the biology and population dynamics of marine pelagic fishes distributed at both sides of the Gibraltar Strait, as well as additional population genetic analyses including temporal series are needed to further understand the factors that promote or prevent gene flow of these species across the Atlantic-Mediterranean transition.

The existence of two different subspecies (S. p. pilchardus and S. p. sardina) as previously reported based on meristic studies [22, 30], and mitochondrial control region sequence haplotypes frequency differences [31] was not supported by population genetic analyses (R ST pairwise comparisons, AMOVA test, and estimations of migration rates) based on microsatellite data. However, these results need to be taken with caution since one of the subspecies (S. p. pilchardus) was only represented by a single location (Pasajes). A more thorough sampling of sardine at North Atlantic locations would be mandatory to further test the validity of the two subspecies using microsatellite allele frequency data.

The discordant genetic structuring patterns inferred based on mitochondrial and microsatellite data could indicate that the two different classes of molecular markers may be reflecting different and complementary aspects of the evolutionary history of sardine. The significant genetic structuring evidenced by mitochondrial data might be reflecting past isolation of sardine populations into two distinct groupings during Pleistocene [31]. Afterwards, sardine populations expanded and secondary contact was re-established around the Gibraltar Strait. Microsatellite data reveal the existence of a present day single evolutionary unit that shows weak genetic structuring due to isolation by distance. At micro geographical scale, genetic drift is supposed to overcome gene flow as geographical distance increases [59] because of the effect of different life-history traits such as e.g. larval retention, homing behavior, or reduced dispersal capacity, that need to be further studied in sardines.

Periodic population extinctions and recolonizations at the regional level are common in sardines and other clupeids and may be responsible for the shallow coalescence of mitochondrial genealogies [20]. In this regard, mitochondrial and nuclear markers exhibit different performance in detecting instances of genetic bottlenecks. Mitochondrial control region sequence data support the existence of a past (Pleistocene) genetic bottleneck of sardines in Safi that is only detected at the nuclear level using the IAM. In addition, analyses of microsatellite data under both the SMM and IAM revealed potential genetic bottlenecks at Kavala and Nador, which would be too recent to be detected by mitochondrial data.

Different types of genetic markers occasionally may render contrasting population genetic structure patterns for a given species [21, 60]. In some instances, discordance among marker classes may result from methodological biases, which when appropriately corrected allow obtaining reconciled patterns [21, 60]. In other cases, conflicting results in describing population genetic structure may arise from the differential effects of genetic drift and mutation on a marker class [21]. In such cases, discordance could be interpreted as a source of alternative and complementary information useful for investigating how evolutionary processes at different time scales shape patterns of genetic heterogeneity. In this study, the comparison of two classes of molecular markers with different mutation rates and modes of inheritance has allowed us to gain complementary and broader insights on sardine historical and contemporary population genetics and dynamics, which ultimately could serve to improve fishery management of this commercially important marine pelagic fish species.

Conclusion

The discordant genetic structuring patterns inferred based on mitochondrial and microsatellite data appear to be pointing to complementary aspects of the evolutionary history of sardine. Past isolation of sardine populations into two distinct groupings is supported by mitochondrial data whereas current gene flow within a single evolutionary unit and a weak genetic structuring due to isolation by distance are evidenced by microsatellite data. This study shows that only the combination of molecular markers with different modes of inheritance and mutation rates is able to disentangle the complex patterns of population structure and dynamics of a small marine pelagic fish such as the sardine.

Methods

Sample collection

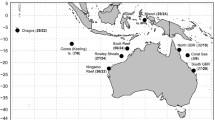

We extended the sample collection of a previous study [61] from about 25–30 to nearly 50 mature sardine specimens per landing port. Overall, population genetic analyses included 433 individuals from six localities (Dakhla, Tantan, Safi, Larache, Quarteira and Pasajes) in the Atlantic Ocean (N = 293) and three localities (Nador, Barcelona and Kavala) in the Mediterranean Sea (N = 140) (Fig. 3). The sardines from the Pasajes location were assigned to the subspecies S. p. pilchardus based on distribution area, and mitochondrial haplotypes frequencies. The sardines from the remaining locations were assigned to the subspecies S. p. sardina based on the same criteria.

Microsatellite genotyping

Genomic DNA of newly analyzed specimens was extracted from fresh muscle following standard phenol-chloroform procedures as previously reported [61]. Specific polymorphic microsatellites (SAR1.5, SAR1.12, SAR2.18, SAR9, SAR19B3, SAR19B5, SARA2F and SARA3C) of S. pilchardus were PCR amplified following optimized reaction conditions [62]. Forward primers were labeled with fluorescent dye (Invitrogen), and PCR amplified products were genotyped on an ABI 3730 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Data collection and sizing of alleles were carried out using GeneMapper v3.7 software (Applied Biosystems). Approximately 10% of the samples were re-run to assess repeatability in scoring.

Statistical analyses

Microsatellite genetic diversity was quantified per locus and per sampling site as the observed and expected heterozygosities [63], number of alleles (NA), and number of alleles standardized to those of the population sample with the smallest size (NS) [64], using both GENETIX 4.02 [65] and FSTAT 2.9.3 [66] (Additional file 2). Deviations from HW equilibrium (by estimating the inbreeding coefficient, FIS) and linkage disequilibrium for each locus and sardine sampling site were assessed using GENEPOP version3.3 [67]. Significance of both analyses was tested with a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) that was run for 1000 batches of 2000 iterations each, with the first 500 iterations discarded before sampling [68]. P values from multiple comparisons were corrected using a Bonferroni correction [69]. Significant differences of genetic diversity measures between S. pilchardus subspecies were tested using a one-way ANOVA test.

A bimodal test for each locus and sampling site was performed to detect possible genotyping errors due to preferential amplification of one of the two alleles, misreading of bands or transcription errors, using the program DROPOUT [70]. Additionally, MICRO-CHECKER v2.23 [36], was used to explore the existence of null alleles, and to evaluate their impact on the estimation of genetic differentiation.

Genetic and spatial variation between populations

Several alternative methods were used to determine sardine population genetic structure. The program STRUCTURE 2.0 [38] uses a model-based Bayesian clustering approach to determine the number of populations (K) with the highest posterior probability and to estimate admixture proportions. Simulations were conducted using an admixture model and correlated allele frequencies between populations (MCMC consisted of 5 × 105 burn-in iterations followed by 2 × 106 sampled iterations). Additionally, the inference of the best value of K was also based on the modal value of ΔK [71]. The range of possible tested K s was from one to nine, and five trial runs of STRUCTURE were carried out for each putative K.

The program STRUCTURAMA [72] infers population genetic structure from genetic data by allowing the number of populations to be a random variable that follows a Dirichlet process prior [39, 40]. We run 1 × 106 MCMC cycles, and we let α (the prior mean of the number of populations) be a random variable. The first 1 × 105 cycles were discarded as burn-in.

We finally applied a Bayesian assignment test as implemented in the program GENECLASS 2.0 [73], which provides the probability for each individual of belonging to the reference population. The computation followed the partial exclusion method [74], and simulation consisted of 10,000 individuals.

The relative contributions of mutation and genetic drift to genetic differentiation of sardine populations could be determined by comparing the variance in allelic identity (FST, IAM [44]) and allelic size (RST, SMM [41]). The program SPAGEDI 1.1 [75] generates a simulated distribution of R ST values (ρR ST ) for testing the null hypothesis of no contribution of SSM to genetic differentiation (ρRST = FST), and the alternative hypothesis that genetic differentiation is caused mainly by SMM-like mutation (ρRST > FST,) [42]. The test rendered a significant result (P < 0.000), and thus, further analyses of genetic differentiation between samples were mostly based on RST pairwise comparisons, as estimated by the program RST-CALC [76].

To determine the amount of genetic variability partitioned within and among populations, an analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) [77] was performed with ARLEQUIN v3.0 [78]. For all calculations, significance was assessed by 20,000 permutations, and reported P-values were Bonferroni adjusted [69]. The Mantel test was used to test correlation between geographical and genetic distances as implemented in GENEPOP version3.3 [67]. The logarithm of geographical distance in kilometers was regressed against either R ST as estimated in RST-CALC [76] or genetic distances based on Bayesian assignment values (DLR) as computed in SPASSIGN [79].

To detect possible genetic bottlenecks (i.e. significant heterozygote excess) in any of the analyzed population samples, we assumed the SMM, IAM, and TPM, and applied the Wilcoxon sign-rank test as implemented in the software BOTTLENECK [80].

Gene flow among sardine populations

The program MIGRATE v 2.1.0 [81] was used to infer the population size parameter Θ (i.e. 4 N e μ, were N e is the effective population size and μ is the mutation rate per site) and the migration rate, M (M = m/μ, were m is the immigration rate per generation) among sardine population samples based on the maximum likelihood method [82]. A subset of 20 individuals per population sample was analyzed due to computational constraints. The analyses were carried under the SMM. F ST estimates and a UPGMA tree were used as starting parameters for the estimation of Θ and M. The MCMC run consisted of ten short and two long chains with 5,000 and 50,000 recorded genealogies respectively, after discarding the first 100,000 genealogies (burn-in). One of every 20 and 200 reconstructed genealogies was sampled for the short and long chains, respectively. To test the null hypothesis that the number of emigrants/ immigrants between the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea has equal rates, a nested mixed-model ANOVA was performed using two variables (basin and location of origin), with emigrant and immigrant rates as repeated measurements.

References

Carvalho GR, Hauser L: Molecular-genetics and the stock concept in fisheries. Rev Fish Biol Fisher. 1994, 4: 326-350. 10.1007/BF00042908.

Zardoya R, Castilho R, Grande C, Favre-Krey L, Caetano S, Marcato S, Krey G, Patarnello T: Differential population structuring of two closely related fish species, the mackerel (Scomber scombrus) and the chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus), in the Mediterranean Sea. Mol Ecol. 2004, 13: 1785-1798. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02198.x.

Magoulas A, Castilho R, Caetano S, Marcato S, Patarnello T: Mitochondrial DNA reveals a mosaic pattern of phylogeographical structure in Atlantic and Mediterranean populations of anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006, 39: 734-746. 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.01.016.

Mariani S, Hutchinson WF, Hatfield EMC, Ruzzante DE, Simmonds EJ, Dahlgren TG, Andre C, Brigham J, Torstensen E, Carvalho GR: North Sea herring population structure revealed by microsatellite analysis. Mar Ecol-Prog Ser. 2005, 303: 245-257. 10.3354/meps303245.

Larsson LC, Laikre L, Palm S, Andre C, Carvalho GR, Ryman N: Concordance of allozyme and microsatellite differentiation in a marine fish, but evidence of selection at a microsatellite locus. Mol Ecol. 2007, 16: 1135-1147. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03217.x.

Hauser L, Ward RD: Advances in Molecular Ecology pp 191-224. 1998, Amsterdam , IOS Press,Population identification in pelagic fish: the limits of molecular markers, Carvalho GR, Series A: Life Sciences, Science Series NATO,

Alvarado Bremer JR, Vinas J, Mejuto J, Ely B, Pla C: Comparative phylogeography of Atlantic bluefin tuna and swordfish: the combined effects of vicariance, secondary contact, introgression, and population expansion on the regional phylogenies of two highly migratory pelagic fishes. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2005, 36: 169-187. 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.12.011.

Waples RS: A multispecies approach to the analysis of gene flow in marine shore fishes. Evolution. 1987, 41: 385-400. 10.2307/2409146.

Martínez P, Gonzalez EG, Castilho R, Zardoya R: Genetic diversity and historical demography of Atlantic bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006, 39: 404-416. 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.07.022.

Nesbø CL, Rueness EK, Iversen SA, Skagen DW, Jakobsen KS: Phylogeography and population history of Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus L.): a genealogical approach reveals genetic structuring among the eastern Atlantic stocks. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2000, 267: 281-292. 10.1098/rspb.2000.0998.

Carlsson J, McDowell JR, Diaz-Jaimes P, Carlsson JE, Boles SB, Gold JR, Graves JE: Microsatellite and mitochondrial DNA analyses of Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus thynnus) population structure in the Mediterranean Sea. Mol Ecol. 2004, 13: 3345-3356. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02336.x.

Grewe PM, Appleyard SA, Ward RD: Determining genetic stock structure of bigeye tuna in the Indian Ocean using mitochondrial DNA and DNA microsatellites. Report for the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation FRDC No 97/122 Hobart:FRDC. 2000

Graves JE, McDowell JR: Stock structure of the world's istiophorid billfishes: a genetic perspective. Mar Freshwater Res. 2003, 54: 287-298. 10.1071/MF01290.

Bekkevold D, Andre C, Dahlgren TG, Clausen LAW, Torstensen E, Mosegaard H, Carvalho GR, Christensen TB, Norlinder E, Ruzzante DE: Environmental correlates of population differentiation in Atlantic herring. Evolution. 2005, 59: 2656-2668.

Gyory J, Beal LM, Bischof B, Mariano AJ, Ryan EH: Website title "The Agulhas Current." Ocean Surface Currents. [http://oceancurrents.rsmas.miami.edu/atlantic/agulhas.html]

Alvarado Bremer JR, Stequert B, N.W. R, Ely B: Genetic evidence for inter-oceanic subdivision of bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus) populations. Mar Biol. 1998, 132: 547-557. 10.1007/s002270050420.

Durand JD, Collet A, Chow S, Guinand B, Borsa P: Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA markers indicate unidirectional gene flow of Indo-Pacific to Atlantic bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus) populations, and their admixture off southern Africa. Mar Biol. 2005, 147: 313-322. 10.1007/s00227-005-1564-2.

Tintore J, Violette PE, Blade I, Cruzado A: A study of an intense density front in the eastern alboran sea: the Almeria-Oran front. J Phys Oceanogr. 1998, 18: 1384-1397. 10.1175/1520-0485(1988)018<1384:ASOAID>2.0.CO;2.

Viñas J, Alvarado Bremer J, Pla C: Phylogeography of the Atlantic bonito (Sarda sarda) in the northern Mediterranean: the combined effects of historical vicariance, population expansion, secondary invasion, and isolation by distance. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004, 33: 32-42. 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.04.009.

Grant WS, Bowen BW: Shallow population histories in deep evolutionary lineages of marine fishes: insights from sardines and anchovies and lessons for conservation. J Hered. 1998, 89: 415-426. 10.1093/jhered/89.5.415.

Buonaccorsi VP, McDowell JR, Graves JE: Reconciling patterns of inter-ocean molecular variance from four classes of molecular markers in blue marlin (Makaira nigricans). Mol Ecol. 2001, 10: 1179-1196. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2001.01270.x.

Parrish RH, Serra R, Grant WS: The monotypic sardines, Sardina and Sardinops - Their taxonomy, distribution, stock structure, and zoogeography. Can J of Fish Aquat Sci. 1989, 46: 2019-2036.

Whitehead PJ: FAO species catalogue. Clupeoid fishes of the world (suborder Clupeioidei). An annotated and illustrated catalogue of the herrings, sardines, pilchards, sprats, shads, anchovies and wolf-herrings. Part 1 - Chirocentridae, Clupeidae and Pristigasteridae. 1985, 125: 1-303.

Olivar MP, Salat J, Palomera I: Comparative study of spatial distribution patterns of the early stages of anchovy and pilchard in the NW Mediterranean sea. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2001, 217: 111-120. 10.3354/meps217111.

Somarakis S, Ganias K, Siapatis A, Koutsikopoulos C, Machias A, Papaconstantinou C: Spawning habitat and daily egg production of sardine (Sardina pilchardus) in the eastern Mediterranean. Fish Oceanogr. 2006, 15: 281-292.

Rodríguez JM, Hernandez-Leon S, Barton ED: Mesoscale distribution of fish larvae in relation to an upwelling filament off Northwest Africa. Deep-Sea Res Pt I. 1999, 46: 1969-1984. 10.1016/S0967-0637(99)00036-9.

Spanakis E, Tsimenides N, Zouro E: Genetic differences between populations of sardine, Sardina pilchardus, and anchovy, Engralis encrasicolus, in the Aegean and Ionean seas. J Fish Biol. 1989, 35: 417-437. 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1989.tb02993.x.

Ramon MM, Castro JA: Genetic variation in natural stocks of Sardina pilchardus (sardines) from the western Mediterranean Sea. Heredity. 1997, 78: 520-528. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6881410.

Tinti F, Di Nunno C, Guarniero I, Talenti M, Tommasini S, Fabbri E, Piccinetti C: Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation suggests the lack of genetic heterogeneity in the Adriatic and Ionian stocks of Sardina pilchardus. Mar Biotechnol. 2002, 4: 163-172. 10.1007/s10126-002-0003-3.

Andreu B: Las branquiespinas en la caracterización de las poblaciones de Sardina pilchardus. Invest Pesq. 1969, 33: 425-607.

Atarhouch T, Rüber L, Gonzalez EG, Albert EM, Rami M, Dakkak A, Zardoya R: Signature of an early genetic bottleneck in a population of Moroccan sardines (Sardina pilchardus). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006, 39: 373-383. 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.08.003.

Fishery_statistics: [http://www.fao.org/fi/website/FIRetrieveAction.do?dom=topic&fid=16003]

Belveze H, Erzini K: The influence of hydroclimatic factors on the availability of the sardine (Sardina pilchardus, Walbaum) in the Moroccan Atlantic fishery. FAO Fish Rep. 1983, 291: 285-328.

Kifani S: Approache spatio-temporelle des relations hydroclimat-dynamique des espéces pélagiques en région d'upwelling: cas de la sardine du stock central marocain. Université de Bretagne Occidentale, France. 1995

Chlaida M, Kifani S, Lenfant P, Ouragh L: First approach for the identification of sardine populations Sardina pilchardus (Walbaum 1792) in the Moroccan Atlantic by allozymes. Mar Biol. 2006, 149: 169-175. 10.1007/s00227-005-0185-0.

Van Oosterhout C, Hutchinson WF, Wills DPM, Shipley P: MICRO-CHECKER: software for identifying and correcting genotyping errors in microsatellite data. Mol Ecol Notes. 2004, 4: 535-538. 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2004.00684.x.

Brookfield JFY: A simple new method for estimating null allele frequency from heterozygote deficiency. Mol Ecol. 1996, 5: 453-455. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.1996.00098.x.

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P: Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000, 155: 945-959.

Pella J, Masuda M: The Gibbs and split-merge sampler for population mixture analysis from genetic data with incomplete baselines. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 2006, 63: 576-596. 10.1139/f05-224.

Huelsenbeck JP, Andolfatto P: Inference of population structure under a Dirichlet process model. Genetics. 2007, 175: 1787-1802. 10.1534/genetics.106.061317.

Michalakis Y, Excoffier L: A generic estimation of population subdivision using distances between alleles with special reference for microsatellite loci. Genetics. 1996, 142: 1061-1064.

Hardy OJ, Charbonnel N, Freville H, Heuertz M: Microsatellite allele sizes: A simple test to assess their significance on genetic differentiation. Genetics. 2003, 163: 1467-1482.

DiRienzo A, Peterson AC, Garza JC, Valdes AM, Slatkin M, Freimer N: Mutational processes of simple-sequence repeat loci in human populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994, 91: 3166-3170. 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3166.

Weir BS, Cockerham CC: Estimating F-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution. 1984, 38: 1358-1370. 10.2307/2408641.

Whittaker JC, Harbord RM, Boxall N, Mackay I, Dawson G, Sibly RM: Likelihood-based estimation of microsatellite mutation rates. Genetics. 2003, 164: 781-787.

Avise JC: Conservation genetics in the marine realm. J Hered. 1998, 89: 377-382. 10.1093/jhered/89.5.377.

Graves JE: Molecular insights into the population structures of cosmopolitan marine fishes. J Hered. 1998, 89: 427-437. 10.1093/jhered/89.5.427.

Ward RD, Woodwark M, Skibinski DOF: A comparison of genetic diversity levels in marine, freshwater and anadromous fishes. J Fish Biol. 1994, 44: 213-232. 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1994.tb01200.x.

Avise JC: Phylogeography: the history and formation of species. 2000, Cambridge, Massachussets , Harvard University Press, 447-

Goldstein DB, Roemer GW, Smith DA, Reich DE, Bergman A, Wayne RK: The use of microsatellite variation to infer population structure and demographic history in a natural model system. Genetics. 1999, 151: 797-801.

Ruzzante DE, Mariani S, Bekkevold D, Andre C, Mosegaard H, Clausen LAW, Dahlgren TG, Hutchinson WF, Hatfield EMC, Torstensen E, Brigham J, Simmonds EJ, Laikre L, Larsson LC, Stet RJM, Ryman N, Carvalho GR: Biocomplexity in a highly migratory pelagic marine fish, Atlantic herring. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006, 273: 1459-1464.

DeWoody JA, Avise JC: Microsatellite variation in marine, freshwater and anadromous fishes compared with other animals. J Fish Biol. 2000, 56: 461-473. 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2000.tb00748.x.

O'Reilly PT, Canino MF, Bailey KM, Bentzen P: Inverse relationship between FST and microsatellite polymorphism in the marine fish, walleye pollock (Theragra chalcogramma): implications for resolving weak population structure. Mol Ecol. 2004, 13: 1799-1814. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02214.x.

Ward RD, Grewe PM: Appraisal of molecular genetic techniques in fisheries. Molecular Genetics in Fisheries. Edited by: Carvalho GR, Pitcher TJ. 1995, London , Chapman and Hall, 29-54.

Ruzzante DE: A comparison of several measures of genetic distance and population structure with microsatellite data: bias and sampling variance. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 1998, 55: 1-14. 10.1139/cjfas-55-1-1.

Knutsen H, Jorde PE, Andre C, Stenseth NC: Fine-scaled geographical population structuring in a highly mobile marine species: the Atlantic cod. Mol Ecol. 2003, 12: 385-394. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01750.x.

Hey J, Won YJ, Sivasundar A, Nielsen R, Markert JA: Using nuclear haplotypes with microsatellites to study gene flow between recently separated Cichlid species. Mol Ecol. 2004, 13: 909-919. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.02031.x.

Carreras-Carbonell J, Macpherson E, Pascual M: Population structure within and between subspecies of the Mediterranean triplefin fish Tripterygion delaisi revealed by highly polymorphic microsatellite loci. Mol Ecol. 2006, 15: 3527-3539. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03003.x.

Koizumi I, Yamamoto S, Maekawa K: Decomposed pairwise regression analysis of genetic and geographic distances reveals a metapopulation structure of stream-dwelling Dolly Varden charr. Mol Ecol. 2006, 15: 3175-3189. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03019.x.

Brown KM, Baltazar GA, Hamilton MB: Reconciling nuclear microsatellite and mitochondrial marker estimates of population structure: breeding population structure of Chesapeake Bay striped bass (Morone saxatilis). Heredity. 2005, 94: 606-615. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800668.

Atarhouch T, Rami M, Naciri M, Dakkak A: Genetic population structure of sardine (Sardina pilchardus) off Morocco detected with intron polymorphism (EPIC-PCR). Marine Biology. 2007, 150 (3): 521-528. 10.1007/s00227-006-0371-8.

Gonzalez EG, Zardoya R: Isolation and characterization of polymorphic microsatellites for the sardine, Sardina pilchardus (Clupleidae). Mol Ecol Notes. 2007, 7: 519-521. 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2006.01640.x.

Nei M: Molecular evolutionary genetics. 1987, New York , Columbia University Press

Nei M, Chesser RK: Estimation of Fixation Indexes and Gene Diversities. Ann Hum Genet. 1983, 47: 253-259. 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1983.tb00993.x.

Belkir K, Borsa P, Chickhi L, Raufaste N, Bonhomme F: GENETIX 4.04 Logici el sous Windows TM, pour la Génétique des Populations. 2000, Laboratoire Génome, Populations, Interactions, CNRS UMR 5000, Université de Montpellier II, Montpellier, France.

Goudet J: FSTAT, a Programe to Estimate and Test Gene Diversities and Fixation Indices, Version 2.9.3. 2001, [http://www2.unil.ch/popgen/softwares/fstat.htm]

Raymond M, Rousset F: GENEPOP 3.3: population genetic software for exact test and ecumenism. J Hered. 1995, 86: 248-249.

Guo SW, Thompson EA: Performing the exact test of Hardy-Weinberg proportion for multiple alleles. Biometrics. 1992, 48: 361-372. 10.2307/2532296.

Rice WR: Analysing tables of statistical tests. Evolution. 1989, 43: 223-225. 10.2307/2409177.

McKelvey KS, Schwartz MK: DROPOUT: a program to identify problem loci and samples for noninvasive genetic samples in a capture-mark-recapture framework. Mol Ecol Notes. 2005, 5: 716-718. 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2005.01038.x.

Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J: Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol. 2005, 14: 2611-2620. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x.

Huelsenbeck JP, Huelsenbeck ET, Andolfatto P: Structurama: Bayesian inference of population structure. Bioinformatics.

Baudouin L, Piry S, Cornuet JM: Analytical Bayesian approach for assigning individuals to populations. J Hered. 2004, 95: 217-224. 10.1093/jhered/esh035.

Rannala B, Mountain JL: Detecting immigration by using multilocus genotypes. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997, 94: 9197-9201. 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9197.

Hardy OJ, Vekemans X: SPAGEDi: a versatile computer program to analyse spatial genetic structure at the individual or population levels. Mol Ecol Notes. 2002, 2: 618-620. 10.1046/j.1471-8286.2002.00305.x.

Goldman SJ: Rst Calc: a collection of computer programs for calculating estimates of genetic differentiation from microsatellite data and determining their significance. Mol Ecol. 1997, 6: 881-885. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.1997.00260.x.

Excoffier L, Smouse PE, Quattro JM: Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among DNA haplotypes: application to human mitochondrial DNA restriction data. Genetics. 1992, 131: 479-491.

Excoffier L, Laval G, Schneider S: Arlequin ver. 3.0: An integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol Bioinf online. 2005, 1: 47-50.

Palsson S: Isolation by distance, based on microsatellite data, tested with spatial autocorrelation (SPAIDA) and assignment test (SPASSIGN). Mol Ecol Notes. 2004, 4: 143-145. 10.1046/j.1471-8286.2003.00581.x.

Piry S, Luikart G, Cornuet JM: BOTTLENECK: A computer program for detecting recent reductions in the effective population size using allele frequency data. J Hered. 1999, 90: 502-503. 10.1093/jhered/90.4.502.

Beerli P: MIGRATE- a maximum likelihood program to estimate gene flow using the coalescent. 2003, [http://people.scs.fsu.edu/~beerli/download.html]

Beerli P, Felsenstein J: Maximum-likelihood estimation of migration rates and effective population numbers in two populations using a coalescent approach. Genetics. 1999, 152: 763-773.

Acknowledgements

We thank M.J. San Sebastián, G. Krey, A. Lombarte, R. Cunha, and T. Atarhouch for kindly providing us with samples. We also thank P. Fitze for his help with analyses and insightful comments. Two anonymous reviewers provided constructive comments on a previous version of the manuscript. This work received financial support from a project of the MEC (Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia) to R. Z. (REN 2001-1514/GLO) and AECI-MAE (Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional – Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores) project to T. Atarhouch and R.Z (project n° 168/03/P). E.G.G. was sponsored by a predoctoral fellowship of the MEC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declares that there are no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

EGG carried out the DNA genotyping, performed the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. RZ conceived the study, supervised the genetic studies, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12862_2007_488_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional file 1: Summary statistics for eight microsatellite loci of Sardina pilchardus population samples. The data provided summarizes the statistical analyses (N = sample size, NA = number of alleles per locus, NS = number of alleles per locus standardized to the smallest sample size (42), expected (HE) and observed (HO) heterozygosities and FIS = Wright's statistics) for each locus and sampling site. (PDF 54 KB)

12862_2007_488_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Additional file 2: Allele frequency and allele size for eight microsatellite loci and each sample of Sardina pilchardus. The table shows the allele frequency and allele size values for each locus and sampling site. (PDF 58 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Gonzalez, E.G., Zardoya, R. Relative role of life-history traits and historical factors in shaping genetic population structure of sardines (Sardina pilchardus). BMC Evol Biol 7, 197 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-7-197

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-7-197