Abstract

Background

Wolbachia are endosymbiotic bacteria that commonly infect numerous arthropods. Despite their broad taxonomic distribution, the transmission patterns of these bacteria within and among host species are not well understood. We sequenced a portion of the wsp gene from the Wolbachia genome infecting 138 individuals from eleven geographically distributed native populations of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. We then compared these wsp sequence data to patterns of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) variation of both infected and uninfected host individuals to infer the transmission patterns of Wolbachia in S. invicta.

Results

Three different Wolbachia (wsp) variants occur within S. invicta, all of which are identical to previously described strains in fire ants. A comparison of the distribution of Wolbachia variants within S. invicta to a phylogeny of mtDNA haplotypes suggests S. invicta has acquired Wolbachia infections on at least three independent occasions. One common Wolbachia variant in S. invicta (wSinvictaB) is associated with two divergent mtDNA haplotype clades. Further, within each of these clades, Wolbachia-infected and uninfected individuals possess virtually identical subsets of mtDNA haplotypes, including both putative derived and ancestral mtDNA haplotypes. The same pattern also holds for wSinvictaA, where at least one and as many as three invasions into S. invicta have occurred. These data suggest that the initial invasions of Wolbachia into host ant populations may be relatively ancient and have been followed by multiple secondary losses of Wolbachia in different infected lineages over time. Finally, our data also provide additional insights into the factors responsible for previously reported variation in Wolbachia prevalence among S. invicta populations.

Conclusion

The history of Wolbachia infections in S. invicta is rather complex and involves multiple invasions or horizontal transmission events of Wolbachia into this species. Although these Wolbachia infections apparently have been present for relatively long time periods, these data clearly indicate that Wolbachia infections frequently have been secondarily lost within different lineages. Importantly, the uncoupled transmission of the Wolbachia and mtDNA genomes suggests that the presumed effects of Wolbachia on mtDNA evolution within S. invicta are less severe than originally predicted. Thus, the common concern that use of mtDNA markers for studying the evolutionary history of insects is confounded by maternally inherited endosymbionts such as Wolbachia may be somewhat unwarranted in the case of S. invicta.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Innumerable insects and other terrestrial arthropods are infected with maternally transmitted endosymbionts. While many endosymbionts spread by increasing the fitness of their hosts, others spread by manipulating host reproduction in ways that specifically enhance transmission of infected cytoplasm, even if this results in reduced transmission of nuclear genes [1]. In these latter cases, such symbionts act as parasites. Parasitic endosymbionts are extremely prevalent in nature, and include many bacteria in the genus Wolbachia [2–4]. These endosymbiotic bacteria infect a wide variety of arthropods and filarial nematodes [2–4]. Although Wolbachia infecting filarial nematodes generally are considered mutualists, most Wolbachia strains infecting insects act as parasites. Recent surveys suggest that Wolbachia infect a substantial proportion of insect species, with estimates ranging from 17% [5–7] to 76% [8]. Extrapolation of these estimates suggests that millions of insect species are currently infected with Wolbachia, making these bacteria among the most widespread parasites on earth.

Wolbachia transmission within host species mainly occurs maternally through the egg cytoplasm, and as such, these microbes have evolved several mechanisms to enhance their own transmission that either increase their host's investment in daughters or decrease the reproductive success of uninfected females. These mechanisms include cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI), thelytokous parthenogenesis, feminization of genetic males, and male-killing [for recent reviews see [1, 9, 10]]. In addition to their vertical (maternal) transmission from mother to offspring, several independent lines of evidence clearly show Wolbachia are also horizontally transmitted both within and among different host species [3, 11–18]. However, despite knowledge that Wolbachia can be transmitted horizontally, a general understanding of the frequency and mode of horizontal transmission within natural host populations is poorly documented.

One approach often employed to infer the transmission patterns and evolutionary history of Wolbachia infections within a given host species is to compare patterns of Wolbachia and host mtDNA genetic variation [19–40]. If the two genomes are strictly co-transmitted vertically from mother to offspring as predicted, then there should be strong linkage between a host's mtDNA genome and the associated Wolbachia genome. Depending on the age of infection, such linkage should be observable in patterns of molecular variation of the two genomes such that a given Wolbachia strain is associated with a particular mtDNA haplotype or clade of haplotypes [24, 30, 38, 41–47]. On the other hand, this tight association is lost if horizontal transmission of Wolbachia occurs, in which case one would not necessarily expect concordant patterns of variation between the two genomes. As an example of using this approach, extensive studies of Drosophila simulans have revealed that this species is infected with at least four genetically distinct strains of Wolbachia, presumably representing four independent invasions across three distinct clades of mitochondrial haplotypes [26, 30–37, 44].

Several studies have been conducted examining the distribution and prevalence of Wolbachia infections among native South American populations of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta, as well as the effects of Wolbachia on mtDNA variation in this species. The general findings of these previous studies were: 1) the prevalence of Wolbachia infections varies significantly among different native geographic populations of S. invicta, 2) two divergent mtDNA haplotype lineages and two Wolbachia variants occur within S. invicta, and 3) a strong association between each Wolbachia variant and host mtDNA lineage exists, albeit these latter two conclusions were based on a relatively small number of samples from only two populations [38, 46, 48]. Interestingly, despite the apparent strong association between genomes, as well as evidence for a high fidelity of maternal transmission of Wolbachia within colonies of S. invicta in the field, Shoemaker et al. [46] found no consistent correlation between the presence of Wolbachia and either levels or patterns of mtDNA diversity. That is, levels of mtDNA variation in Wolbachia-infected and uninfected populations were similar and patterns of mtDNA variation within Wolbachia-infected populations did not differ consistently from neutral expectations, despite the prediction that strong positive selection acting on Wolbachia influences the evolutionary dynamics of other cytoplasmic genomes [46]. There are three potential non-mutually exclusive explanations for these puzzling results: 1) Wolbachia infections in S. invicta are sufficiently ancient so that levels of mtDNA variation have re-equilibrated to their levels prior to invasion of Wolbachia, 2) Wolbachia infections are horizontally transmitted within S. invicta such that the two genomes are not strictly co-transmitted as previously suggested, or 3) the evolutionary history of Wolbachia infections within S. invicta involves multiple independent invasions of one or more Wolbachia variants.

The major goal of the present study was to infer the transmission patterns and evolutionary history of Wolbachia infections within S. invicta. To accomplish our objective, we generated sequence data from two portions of the Wolbachia genome present in numerous infected individuals of S. invicta collected throughout the species' native range and subsequently compared these data to patterns of mtDNA variation to determine the extent of Wolbachia strain variation as well as the predominant mode of Wolbachia transmission in this species. In addition, we also use these data to address the issue of whether or not the significant variation in Wolbachia prevalence among fire ant populations is simply due to the presence of different Wolbachia variants in these populations. As we show below, our results based on these extensive sequence data lead to new insights regarding the history of Wolbachia infections in S. invicta, and in so doing, partly explain the paradoxical findings of previous studies on these ants.

Results and discussion

Diversity of Wolbachia strains in S. invicta

Our Wolbachia (wsp) sequence data, which includes partial wsp sequences from 138 Wolbachia-infected individuals, revealed only three unique variants within S. invicta. All three variants are identical to previously reported Wolbachia (wsp) variants from fire ants and fall into one of the two divergent major Wolbachia subgroups comprising Wolbachia strains specific to New World ants (InvA and InvB) [49, 50]. Two of the variants were identical to Wolbachia variants previously reported to infect S. invicta (wSinvictaA and wSinvictaB; InvA and InvB subgroups, respectively), whereas the third "new" variant is identical to a variant previously reported to infect the closely related fire ant species S. richteri (wSrichteriA; InvA subgroup) [38].

Additionally, the Wolbachia 16S sequence data from a subset of infected individuals did not reveal any new Wolbachia variants within S. invicta. The 16S sequences from all individuals infected with the variants wSinvictaA and wSrichteriA (based upon wsp sequences) were identical to each other as were the 16S sequences from individuals infected with wSinvictaB. However, the 16S sequences from individuals infected with the variants wSinvictaA and wSrichteriA differed by a single nucleotide substitution from those in individuals infected with wSinvictaB. All 16S sequences belong to the A group of Wolbachia (as opposed to the A and B groups for wsp sequences). This discrepancy between the two genes most likely results from an historical recombination event within the Wolbachia genome, which perhaps is not unexpected given previous studies showing recombination of Wolbachia genomes commonly occurs [51, 52].

Transmission patterns of Wolbachia in S. invicta

Both Wolbachia (wsp) and mtDNA sequence data were available for 133 of 138 infected individuals (Table 1 and Figure 1): MtDNA sequence data were lacking for the remaining five Wolbachia-infected individuals, which are excluded from the comparative analyses below. The distribution of all mtDNA haplotypes within each of the eleven populations is shown in Table 2 and the particular haplotypes that are associated with Wolbachia infections is shown in Table 2 and Figure 1. A comparison of wsp and mtDNA sequence variation suggests a complex evolutionary history of Wolbachia infections in S. invicta, involving multiple independent invasions of Wolbachia into S. invicta followed by frequent secondary loss of infections in different maternal lineages. Indeed, these data suggest that at least six independent invasions involving three different Wolbachia variants have occurred into S. invicta (scenario 1 of Figure 1). The variant wSinvictaB apparently invaded S. invicta on two separate occasions. One of these invasions is most likely a rather recent event, as it is associated with only three individuals, all of which harbour an identical mtDNA haplotype (haplotype #51; incidentally, all three individuals also are infected with the wSrichteriA variant). The other invasion of wSinvictaB into S. invicta is presumably more ancient as evidenced by the strong association of this variant with a highly divergent mtDNA clade comprising closely related mtDNA haplotypes (i.e., clade I in Figure 1). There appears to have been a single invasion of the wSrichteriA variant into S. invicta, as its presence is limited to a single clade of mtDNA haplotypes (clade IV), all of which come from individuals collected from two populations in southern Brazil: Arroio dos Ratos and Rincão dos Cabrais (Figure 2; see Ahrens et al. [53]). Finally, the association of Wolbachia variant wSinvictaA with three highly divergent clades of mtDNA haplotypes (clades II, III, and V) is consistent with three separate, rather ancient invasions of this Wolbachia strain into S. invicta.

Bayesian phylogenetic tree (A) and minimum spanning network (B) of mtDNA haplotypes from S. invicta. Both the Bayesian phylogenetic tree and minimum spanning network of mtDNA haplotypes from S. invicta reprinted from Ahrens et al. [53]. Haplotypes associated with the three Wolbachia variants in S. invicta are indicated by coloured bars/circles. For each mtDNA haplotype, the coloured areas of bars/circles are proportional to the number of Wolbachia-infected individuals, also indicated by the values in parentheses. The five haplotype clades in the Bayesian tree harbouring Wolbachia infected individuals are linked to their corresponding haplotype clusters by Roman numerals I-V. Purported invasion/horizontal transmission events of Wolbachia into S. invicta under scenarios 1 and 2 are indicated by the grey and black coloured bars, respectively, on the Bayesian tree. Also indicated is the evolutionary transition of variant wSinvictaA to variant wSrichteriA (black box to blue box). See text for more details.

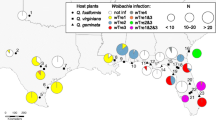

Distribution and prevalence of Wolbachia variants in eleven sampled populations of S. invicta. Each pie diagram shows the proportions of Wolbachia-infected (separately for each variant) and uninfected individuals in each geographic population (sample sizes in parentheses). The native range of S. invicta as currently understood is indicated by green shading and is based on Buren et al. [63], Trager [57], and Pitts [64].

An alternative scenario, however, is that there have been only three independent invasions of Wolbachia into S. invicta: Two of these invasions involve wSinvictaB (as described above) whereas the third invasion involves Wolbachia variant wSinvictaA (scenario 2 of Figure 1). Under this scenario such a single invasion of wSinvictaA into S. invicta presumably would have to be quite ancient, since it requires that the infection would have had to be present in the common ancestor of clades II-V (see Figure 1). Assuming a divergence rate of 2% per million years [54], our estimate of the net average nucleotide divergence among all mtDNA haplotypes comprising clades II-V (2.4%; Ahrens et al. [53]) would suggest this invasion of wSinvictaA (or most recent Wolbachia sweep) occurred roughly 1.2 mya. An additional caveat of this scenario is that wSrichteriA is not a novel, independently acquired Wolbachia infection but instead represents a derived variant of wSinvictaA (see Figure 1).

Although these rather restrictive conditions might lead one to conclude that a single invasion of wSinvictaA into S. invicta seems unlikely, this is not necessarily the case. First, whilst it is tempting to interpret the high levels of divergence among mtDNA haplotypes as indicating an ancient invasion of Wolbachia, one must be cautious when using estimates of mtDNA sequence divergence for inferring evolutionary rates simply because such high divergence may be the result a Wolbachia-driven increase in mtDNA substitution rates [39]. If true, then we may have substantially overestimated the time of invasion of wSinvictaA into S. invicta. A necessary requirement, however, is that individuals comprising the separate clades correspond to different lineages or populations that themselves are connected by little or no migration, since significant gene exchange would erase the signature of high divergence among clades. Otherwise, the most plausible explanation for the association of wSinvictaA with these divergent clades is that multiple independent invasions have occurred into S. invicta (i.e., scenario 1 above). For most populations currently infected with wSinvictaA, the condition of substantially reduced gene flow among populations holds: Ahrens et al. [53] found that genetic divergence among populations is very high and that mtDNA genetic variation is correlated with geography such that 76 out of 81 mtDNA haplotypes identified in S. invicta were exclusive to single populations. Thus, the likelihood of a single invasion seems much more reasonable when we consider not only the possible effects of Wolbachia within populations but also how Wolbachia infections can accelerate divergence among populations (divergence among mtDNA lineages), especially those connected by very limited gene flow. Finally, we should also point out that the additional above requirement that wSrichteriA is a derived variant of wSinvictaA also is quite reasonable given that these two strains differ by only a single nucleotide substitution at the highly evolving wsp gene.

Regardless of the presumed number of invasions of Wolbachia into S. invicta (three, six, or perhaps more), it is clear that the secondary loss of Wolbachia infections from host lineages following invasion is very common. Such frequent loss of infections is most obvious when one considers the fact that uninfected individuals harbour both derived mtDNA haplotypes and ancestral haplotypes inferred to be associated with the original infection (Figure 1). Previously, Shoemaker et al. [48] estimated that the fidelity of maternal transmission of Wolbachia in S. invicta in nature generally is very high (>99%), but nonetheless is not perfect, ranging from 90–100% within different matrilines.

Thus, our data partly resolve the paradox of a lack of a consistent correlation between the presence of Wolbachia and either levels or patterns of mtDNA diversity in S. invicta. Clearly, the previous assertion of strictly vertical transmission of Wolbachia in fire ants breaks down upon finer-scale analysis. Multiple independent invasions of Wolbachia into S. invicta have occurred, and in every case these have been followed by frequent secondary loss of infections. Thus, although we predicted a strong association between the mtDNA and Wolbachia genomes since both are co-transmitted from mother to offspring, the strong association of the two genomes in fire ants clearly has broken down over time due to frequent horizontal transmission and secondary loss of Wolbachia strains [26, 36, 44–46, 55].

Wolbachia distribution and prevalence in S. invicta

Variation in the distribution and prevalence of Wolbachia in natural populations of S. invicta may be due to: 1) presence of different Wolbachia variants within and among populations 2) genetic differences among host individuals from different populations or 3) genetic drift [48]. To attempt to address this issue, we examined the Wolbachia strain identities and their corresponding frequencies within each of the eleven sampled populations of S. invicta. If variation in Wolbachia prevalence is due simply to differences in the particular Wolbachia variants or combinations of variants within and among these populations, then we might expect that despite differences in overall Wolbachia prevalence among populations the prevalence of any particular Wolbachia variant is similar in each of the host populations where it occurs. Thus, a simple explanation for the observed variation in prevalence may be that the array of Wolbachia variants differs among host populations. On the other hand, if this variation results from genetic differences among host individuals from different populations, then one might expect that the prevalence of specific Wolbachia variants varies among different host populations, and possibly that the variants are associated with quite different mtDNA haplotypes in each population. Although the effects of Wolbachia on S. invicta are currently unknown, we would expect infection prevalence to vary stochastically if Wolbachia do not have any measurable fitness or sex ratio effects on their fire ant hosts.

The distribution and prevalence of the three Wolbachia variants within the eleven sampled populations of S. invicta is shown in Figure 2. The wSinvictaA variant occurs at similar prevalence (11.4–27.8% of individuals) in four of the five populations where it is found, possibly indicating this low prevalence represents the stable equilibrium frequency of this variant. The similar prevalence of wSinvictaA in different populations that are both genetically differentiated and separated by great geographical and ecological differences [53] suggests that the dynamics and prevalence of this variant are most likely not strongly affected by its host or environment. The wSinvictaB variant is largely confined to individuals collected from the southwestern populations of Corrientes and Roldán/Rosario. This variant occurs at relatively high prevalence in these populations (39.2–75.0%). Finally, the wSrichteriA variant has a very restricted distribution and is found only in individuals from the Arroio dos Ratos and Rincão dos Cabrais populations in the southernmost portion of Brazil. Our survey data revealed that 36% of all colonies surveyed from these populations harbour this Wolbachia variant.

Together, these data indicate that the variation in Wolbachia prevalence among populations can be explained largely by differences in the array of Wolbachia variants within host populations. Even so, we cannot discount completely a role for host effects in determining Wolbachia prevalence given the very high levels of genetic differentiation among populations [46, 53, 56]. Additionally, while our data do not imply an obvious role for environmental conditions affecting Wolbachia dynamics, it is interesting to note the apparent positive correlation between Wolbachia prevalence and latitude. An analogous pattern previously has been reported for a Wolbachia variant infecting the beetle Chelymorpha alternans. In this host species, Wolbachia prevalence apparently is lower in areas experiencing longer dry seasons and higher average daily temperatures [24]. Thus, although unlikely, it remains possible that the overall Wolbachia infection dynamics in S. invicta are influenced by differences in environmental conditions as well, with higher Wolbachia prevalence occurring in the more southerly temperate populations.

Finally, our results combined with mtDNA data from earlier studies argue against the previous hypothesis that variation in Wolbachia prevalence is simply due to the recent invasion and ongoing spread of Wolbachia in S. invicta. First, a substantial number of polymorphic sites were found in the mtDNA sequences comprising each of five clades (I-V), indicating the Wolbachia infections are sufficiently ancient enough that numerous mtDNA mutations have accumulated since the most recent invasion(s) of Wolbachia. Assuming a divergence rate of 2% per million years [54], estimates of the average sequence divergence among mtDNA haplotypes within clades I-V (0.1–1.2%; Ahrens et al. [53]) would suggest the most recent invasion of Wolbachia (or most recent Wolbachia sweep) within any of these clades roughly occurred at least 50,000 years BP (Although Wolbachia endosymbionts may accelerate divergence between lineages or populations, recurrent Wolbachia sweeps have the opposite effect on differentiation within populations and result in substantially reduced mtDNA variation within populations [30, 39]). The finding that the composition and diversity of mtDNA haplotypes found in infected and uninfected individuals within populations are virtually identical clearly suggests that uninfected individuals are derived from infected lineages via incomplete maternal transmission of Wolbachia and lends further support to the hypothesis that Wolbachia infections in S. invicta are evolutionarily old. An alternative possibility, which we consider less likely, is that there has been rampant horizontal transmission of the same Wolbachia variants within and among S. invicta populations.

Conclusion

The evolutionary history of Wolbachia in S. invicta is far more complex than previously recognized: at least three and possibly as many as six horizontal transmission events involving three different variants have occurred into S. invicta. Further, in every case these independent acquisitions of Wolbachia have been followed by multiple independent losses of Wolbachia infections over time. Indeed, we should note that if loss of Wolbachia infection occurs as commonly as our data suggest, then we likely have underestimated the number of invasions or horizontal transmissions of Wolbachia. These extensive sequence data also suggest that the significant variation in Wolbachia prevalence among fire ant populations most likely is due simply to the presence of different variants limited to specific regions of S. invicta's range, but roles for both host effects and the environment in accounting for the observed patterns cannot be excluded. Our results also partly explain the previous puzzling findings of no clear effects of Wolbachia infection on patterns of mtDNA variation and substitution in fire ants [46]. Wolbachia transmission over evolutionary time appears to be uncoupled from that of the mtDNA genome such that the predicted effect of Wolbachia in reducing host mtDNA variation is not clearly evident as originally predicted. Thus, our previous concern that recurrent Wolbachia sweeps within fire ant populations may confound the use of mtDNA markers for studying the evolutionary history of fire ants (i.e. phylogeographic studies, identification of source populations), as the invasion of new strains would erase all pre-existing variation, seems somewhat unwarranted.

On the other hand, the high levels of divergence among mtDNA haplotype clades (~3.2% [53]) are analogous to patterns reported for the two Wolbachia-infected insect species, Drosophila recens and D. simulans, and may be the footprint of another predicted effect of Wolbachia infections, namely, an accelerated mtDNA substitution rate as a result of recurrent Wolbachia sweeps (see Shoemaker et al. [39] for full discussion). For example, Shoemaker et al. [39] observed an mtDNA-specific accelerated rate of evolution in D. recens, a species in which virtually all individuals are infected by a single Wolbachia strain, relative to the closely related uninfected species D. subquinaria. In D. simulans, previous studies have revealed that despite very little sequence variation within each of the three defined mtDNA haplotype clades, substantial differentiation exists among these clades [26, 30–37, 44]. Although no formal comparative analyses have been conducted in either S. invicta or D. simulans to test the above hypothesis, one possible explanation for the high level of divergence among these well-defined mtDNA haplotype clades in both species is that it results from Wolbachia-driven acceleration in the mtDNA substitution rate [39]. Together, these three studies lend support to the hypothesis that maternally-inherited endosymbiont infections may increase the rate of substitution in mtDNA [39]. Clearly, additional comparative studies in other insects are needed to test the generality of this hypothesis, especially since such effects have important consequences for the assumptions of neutrality and use of mtDNA as a molecular clock in insects.

Methods

Collection and identification of ants

Individuals of S. invicta were collected from native populations in Argentina and Brazil in 1992 and 1998 (Table 1). Multiple workers and winged virgin queens were collected from each of 555 colonies representing eleven geographic populations distributed over much of the known native range of S. invicta (see Figure 1 of Ahrens et al. [53] for locations). All collected individuals were identified as S. invicta by J. P. Pitts using species-informative morphological characters [57, 58].

Sequencing of Wolbachia strains

DNA was extracted from a single individual from each of the 555 colonies using the Puregene DNA isolation kit (Gentra Systems) [38, 59]. We previously screened all 555 DNA extracts for the presence of Wolbachia by means of PCR using the primers wsp 81F and wsp 691R [48, 59, 60]. These wsp primers amplify a portion of a highly-variable gene encoding the Wolbachia outer surface protein [59, 60]. Our previous survey of S. invicta revealed that 138 of the 555 individuals (colonies) were Wolbachia-infected (see Table 1). For the present study, we sequenced a portion of the wsp gene from all 138 infected individuals using the above primers. Wolbachia DNA was PCR-amplified in 30-μL volumes, with the PCR reaction components and thermal cycling conditions identical to those described in Shoemaker et al. [38]. Wsp PCR amplicons were purified for sequencing using Ampure magnetic beads (Agencourt Bioscience Corp.) and subsequently used directly in standard fluorescent cycle-sequencing PCR reactions (ABI Prism Big Dye terminator chemistry, Applied Biosystems). Sequencing reactions were purified using CleanSEQ magnetic beads (Agencourt Bioscience Corp.) and run on an ABI 3700 sequencer at the UW Biotechnology Center DNA Sequencing Laboratory.

Initial sequencing results of the wsp gene revealed the presence of more than one Wolbachia strain in three individuals of S. invicta (i.e., multiple peaks or frameshifts in electropherogram profiles were observed). For these three individuals, Wolbachia DNA was PCR-amplified as described above, except the final extension at 72°C was increased to 30 minutes. PCR amplicons were cloned directly into a vector following manufacturer's suggestions (Topo TA cloning kit, Invitrogen corp.) and resulting colonies screened for the presence of the desired wsp PCR insert using the wsp primers. For each individual, PCR-amplified products from ten colonies (which presumably had the wsp insert) were purified and sequenced as described above.

We also PCR-amplified and sequenced a 945 base portion of the Wolbachia 16S gene using primers specific to this region [3] from a subset of the infected individuals within each population in an attempt to further characterize and identify unique Wolbachia strains (27 sequences total). PCR reaction components and thermal cycling conditions were identical to those described in O'Neill et al. [3]. Purification and sequencing of 16S amplicons, as well as cloning and sequencing of individuals possessing more than one Wolbachia strain, were carried out as described for the wsp gene above.

Comparing Wolbachia (wsp) and mtDNA variation

Both the phylogeny and minimum spanning network of 81 unique mtDNA haplotypes representing 400 individuals (colonies) from the eleven populations used in the present study were generated previously by Ahrens et al. [53] using MrBayes 3.0 [61] and ARLEQUIN ver. 2.000 [62], respectively. Both methods of analysis identified six well-supported clades (clusters) of closely related mtDNA haplotypes, with each clade separated from the others by at least 18 mutational steps. With few exceptions, each clade is comprised of mtDNA haplotypes present in individuals from only one or two geographically proximal populations of S. invicta [for a more detailed description, see [53]]. For the present study, we used our wsp gene sequence data to determine the infection status, infection frequency, and strain identity for individuals of each mtDNA haplotype within the pre-existing networks.

References

Stouthamer R, Breeuwer JAJ, Hurst GDD: Wolbachia pipientis: Microbial manipulator of arthropod reproduction. Annual Review of Microbiology. 1999, 53: 71-102. 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.71.

Werren JH, O'Neill SL: The evolution of heritable symbionts. Influential Passengers: Inherited Microorganisms and Arthropod Reproduction. Edited by: O'Neill SL, Hoffmann AA, Werren JH. 1997, New York , Oxford University Press, 1-41.

O'Neill SL, Giordano R, Colbert AME, Karr TL, Robertson HM: 16S rRNA phylogenetic analysis of the bacterial endosymbionts associated with cytoplasmic incompatibility in insects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1992, 89: 2699-2702.

Bandi C, Anderson T, Genchi C, Blaxter M: Phylogeny of Wolbachia in filarial nematodes. Proceedings of The Royal Society of London: Series B, Biological Sciences. 1998, 265 (1413): 2407-2413. 10.1098/rspb.1998.0591.

Werren JH, Guo L, Windsor DW: Distribution of Wolbachia in Neotropical arthropods. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London: Series B, Biological Sciences. 1995, 262: 197-204.

Werren JH, Windsor DM: Wolbachia infection frequencies in insects: Evidence of a global equilibrium?. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London: Series B, Biological Sciences. 2000, 267: 1277-1285. 10.1098/rspb.2000.1139.

West SA, Cook J, Werren JH, Godfrey HCJ: Wolbachia in two insect host-parasitoid communities. mol ecol. 1998, 7: 1457-1465. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00467.x.

Jeyaprakash A, Hoy MA: Long PCR improves Wolbachia DNA amplification: wsp sequences found in 76% of sixty-three arthropods. Insect Molecular Biology. 2000, 9: 393-405. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00203.x.

Werren JH: Biology of Wolbachia. Annual Review of Entomology. 1997, 42: 537-609. 10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.587.

Stevens L, Giordano R, Fialho RF: Male-killing, nematode infections, bacteriophage infection, and virulence of cytoplasmic bacteria in the genus Wolbachia. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 2001, 32: 519-545. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114132.

Huigens ME, deAlmeida RP, Boons PAH, Luck RF, Stouthamer R: Natural interspecific and intraspecific horizontal transfer of parthenogensis-inducing Wolbachia in Trichogramma wasps. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London: Series B, Biologial Sciences. 2004, 271 (1538): 509-515. 10.1098/rspb.2003.2640.

Vavre F, Fleury F, Lepetit D, Fouillet P, Bouletreau: Phylogenetic evidence for horizontal transmission of Wolbachia in host-parasitoid associations. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 1999, 16: 1711-1723.

Heath BD, Butcher RDJ, Whitfield WGF, Hubbard SF: Horizontal transfer of Wolbachia between phylogenetically distant insect species by a naturally occurring mechanism. Current Biology. 1999, 9: 313-316. 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80139-0.

van Meer MMM, Witteveldt J, Stouthamer R: Phylogeny of the arthropod endosymbiont Wolbachia based on the wsp gene. Insect Molecular Biology. 1999, 8 (3): 399-408. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1999.83129.x.

Huigens ME, Luck RF, Klaassen RHG, Maas MFPM, Timmermans MJTN, Stouthamer R: Infectious parthenogenesis. Nature. 2000, 405 (6783): 178-179. 10.1038/35012066.

Werren JH, Zhang W, Guo LR: Evolution and phylogeny of Wolbachia: Reproductive parasites of arthropods. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London: Series B, Biological Sciences. 1995, 261: 55-71.

Noda H, Miyoshi T, Zhang Q, Watanabe K, Deng K, Hoshizaki S: Wolbachia infection shared among planthoppers (Homoptera: Delphacidae) and their endoparasite (Strepsiptera: Elenchidae): a probable case of interspecies transmission. Mol Ecol. 2001, 10 (8): 2101-2106. 10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01334.x.

Schilthuizen M, Stouthamer R: Horizontal transmission of parthenogenesis-inducing microbes in Trichogramma wasps. Proceedings of the Royal society of London: Series B, Biological Sciences. 1997, 264: 361-366. 10.1098/rspb.1997.0052.

Cordaux R, Michel-Salzat A, Frelon-Raimond M, Rigaud T, Bouchon D: Evidence for a new feminizing Wolbachia strain in the isopod Armadillidium vulgare: Evolutionary implications. Heredity. 2004, 93 (1): 78-84. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800482.

Rigaud T, Bouchon D, Souty-Grosset C, Raimond R: Mitochondrial DNA polymorphism, sex ratio distorters, and population genetics in the isopod Armadillidium vulgare. Genetics. 1999, 152: 1669-1677.

Michel-Salzat A, Cordaux R, Bouchon D: Wolbachia diversity in the Porcellionides pruinosus complex of species (Crustacea : Oniscidea): evidence for host-dependent patterns of infection. Heredity. 2001, 87: 428-434. 10.1046/j.1365-2540.2001.00920.x.

Guillemaud T, Pasteur N, Rousset F: Contrasting levels of variability between cytoplasmic genomes and incompatibility types in the mosquito Culex pipiens. Proceedings of The Royal Society of London: Series B, Biological Sciences. 1997, 264: 245-251. 10.1098/rspb.1997.0035.

Rousset F, Solignac M: Evolution of single and double Wolbachia symbioses during speciation in the Drosophila simulans complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1995, 92: 6389-6393.

Keller GP, Windsor DM, Saucedo JM, Werren JH: Reproductive effects and geographical distributions of two Wolbachia strains infecting the Neotropical beetle, Chelymorpha alternans Boh. (Chrysomelidae, Cassidinae). Molecular Ecology. 2004, 13 (8): 2405-2420. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02213.x.

Behura SK, Sahu SC, Mohan M, Nair S: Wolbachia in the Asian rice gall midge, Orseolia oryzae (Wood- Mason): correlation between host mitotypes and infection status. Insect Mol Biol. 2001, 10 (2): 163-171. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2001.00251.x.

Turelli M, Hoffmann AA, McKechnie SW: Dynamics of cytoplasmic incompatibility and mtDNA variation in natural Drosophila simulans populations. Genetics. 1992, 132 (3): 713-723.

Marcade I, Souty-Grosset C, Bouchon D, Rigaud T, Raimond R: Mitochondrial DNA variability and Wolbachia infection in two sibling woodlice species. Heredity. 1999, 83: 71-78. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6885380.

Rokas A, Atkinson RJ, Brown GS, West SA, Stone GN: Understanding patterns of genetic diversity in the oak gallwasp Biorhiza pallida: demographic history or a Wolbachia selective sweep?. Heredity. 2001, 87: 294-304. 10.1046/j.1365-2540.2001.00872.x.

Jiggins FM: Male-killing Wolbachia and mitochondrial DNA: Selective sweeps, hybrid introgression and parasite population dynamics. Genetics. 2003, 164 (1): 5-12.

Turelli M, Hoffmann AA: Rapid spread of an inherited incompatibility factor in California Drosophila. Nature. 1991, 353: 440-442. 10.1038/353440a0.

Ballard JWO: Comparative genomics of mitochondrial DNA in Drosophila simulans. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 2000, 51: 64-75.

Ballard JWO: Sequential evolution of a symbiont inferred from the host: Wolbachia and Drosophila simulans. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2004, 21 (3): 428-442. 10.1093/molbev/msh028.

Ballard JWO, Chernoff B, James AC: Divergence of mitochondrial DNA is not corroborated by nuclear DNA, morphology, or behavior in Drosophila simulans. Evolution. 2002, 56 (3): 527-545.

Ballard JWO, Hatzidakis OJ, Karr TL, Kreitman M: Reduced variation in Drosophila simulans mitochondrial DNA. Genetics. 1996, 144: 1519-1528.

Dean MD, Ballard KJ, Glass A, Ballard JWO: Influence of two Wolbachia strains on population structure of East African Drosophila simulans. Genetics. 2003, 165 (4): 1959-1969.

James AC, Dean MD, McMahon ME, Ballard JWO: Dynamics of double and single Wolbachia infections in Drosophila simulans from New Caledonia. Heredity. 2002, 88: 182-189. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800025.

James AC, Ballard JWO: Expression of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila simulans and its impact on infection frequencies and distribution of Wolbachia pipientis. Evolution. 2000, 54: 1661-1672.

Shoemaker DD, Ross KG, Keller L, Vargo EL, Werren JH: Wolbachia infections in native and introduced populations of fire ants (Solenopsis spp.). Insect Molecular Biology. 2000, 9: 661-673. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00233.x.

Shoemaker DD, Dyer KA, Ahrens M, McAbee K, Jaenike J: Decreased diversity but increased substitution rate in host mtDNA as a consequence of Wolbachia endosymbiont infection. Genetics. 2004, 168: 2049-2058. 10.1534/genetics.104.030890.

Charlat S, Nirgianaki A, Bourtzis K, Mercot H: Evolution of Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila simulans and D. Sechellia. Evolution. 2002, 56 (9): 1735-1742.

Caspari E, Watson GS: On the evolutionary importance of cytoplasmic sterility in mosquitoes. Evolution. 1959, 13: 568-570.

Fine PEM: On the dynamics of symbiote-dependent cytoplasmic incompatibility in Culicine mosquitoes. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 1978, 30: 10-18. 10.1016/0022-2011(78)90102-7.

Prout T: Some evolutionary possibilities for a microbe that causes incompatibility in its host. Evolution. 1994, 48: 909-911.

Turelli M, Hoffmann AA: Cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila simulans: Dynamics and parameter estimates from natural populations. Genetics. 1995, 140: 1319-1338.

Turelli M: Evolution of incompatibility-inducing microbes and their hosts. Evolution. 1994, 48: 1500-1513.

Shoemaker DD, Keller G, Ross KG: Effects of Wolbachia on mtDNA variation in two fire ant species. Mol Ecol. 2003, 12 (7): 1757-1771. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01864.x.

Charlat S, Bonnavion P, Mercot H: Wolbachia segregation dynamics and levels of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila sechellia. Heredity. 2003, 90 (2): 157-161. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800211.

Shoemaker DD, Ahrens M, Sheill L, Mescher M, Keller L, Ross KG: Distribution and prevalence of Wolbachia infections in native populations of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta (Hymenoptera : Formicidae). Environmental Entomology. 2003, 32 (6): 1329-1336.

Tsutsui ND, Kauppinen SN, Oyafuso AF, Grosberg RK: The distribution and evolutionary history of Wolbachia infection in native and introduced populations of the invasive argentine ant (Linepithema humile). Mol Ecol. 2003, 12 (11): 3057-3068. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01979.x.

Van Borm S, Wenseleers T, Billen J, Boomsma JJ: Cloning and sequencing of wsp encoding gene fragments reveals a diversity of co-infecting Wolbachia strains in Acromyrmex leafcutter ants. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2003, 26: 102-109. 10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00298-1.

Jiggins FM: The rate of recombination in Wolbachia bacteria. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2002, 19 (9): 1640-1643.

Werren JH, Bartos J: Recombination in Wolbachia. Current Biology. 2001, 11: 431-435. 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00101-4.

Ahrens M, Ross KG, Shoemaker DD: Phylogeographic structure of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta in its native South American range: Roles of natural barriers and habitat connectivity. Evolution. 2005, in press:

Brower AVZ: Rapid morphological radiation and convergence among races of the butterfly Heliconius errato inferred from patterns of mitochondrial DNA evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1994, 91: 6491-6495.

Shoemaker DD, Katju V, Jaenike J: Wolbachia and the evolution of reproductive isolation between Drosophila recens and Drosophila subquinaria. Evolution. 1999, 53 (4): 1157-1164.

Ross KG, Shoemaker DD: Species delimitation in native South American fire ants. Molecular Ecology. 2005, in press:

Trager JC: A revision of the fire ants, Solenopsis geminata group (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae). Journal of the New York Entomological Society. 1990, 99 (2): 141-198.

Pitts JP, McHugh JV, Ross KG: Revision of the fire ants of the Solenopsis saevissima species-group (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa. 2005, in press:

Zhou W, Rousset F, O'Neill S: Phylogeny and PCR-based classification of Wolbachia strains using wsp gene sequences. Proceedings of The Royal Society of London: Series B, Biological Sciences. 1998, 265: 509-515. 10.1098/rspb.1998.0324.

Braig HR, Zhou W, Dobson S, O'Neill SL: Cloning and characterization of a gene encoding the major surface protein of the bacterial endosymbiont Wolbachia. Journal of Bacteriology. 1998, 180: 2373-2378.

Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F, Nielsen R, Bollback JP: Evolution - Bayesian inference of phylogeny and its impact on evolutionary biology. Science. 2001, 294 (5550): 2310-2314. 10.1126/science.1065889.

Schneider S, Roessli D, Excoffier L: Arlequin ver. 2.000: A software for population genetic data analysis. 2000, University of Geneva, Switzerland , Genetics Biometry Laboratory

Buren WF, Allen GE, Whitcomb WH, Lennartz FE, Williams RN: Zoogeography of the imported fire ants. Journal of the New York Entomological Society. 1974, 82: 113-124.

Pitts JP: A cladistic analysis of the Solenopsis saevissima species-group (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomology. 2002, Athens, GA , University of Georgia

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Laurent Keller, Mark Mescher, and Ken Ross for their invaluable assistance in the collecting of ants used for the present study. We also thank Ken Ross and three anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. This study was supported by grants from the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at the University of Wisconsin, the United States Department of Agriculture NRICGP, and the U.S. National Science Foundation to DDS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

MEA carried out the majority of the molecular work and performed phylogenetic data analyses. DDS designed and coordinated the study, collected all of the ants used for the study, carried out a portion of the molecular work, and performed most of the data analyses. Both authors contributed to writing the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahrens, M.E., Shoemaker, D. Evolutionary history of Wolbachia infections in the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. BMC Evol Biol 5, 35 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-5-35

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-5-35