Abstract

Background

It is often proposed that females should select genetically dissimilar mates to maximize offspring genetic diversity and avoid inbreeding. Several recent studies have provided mixed evidence, however, and in some instances females seem to prefer genetically similar males. A preference for genetically similar mates can be adaptive if outbreeding depression is more harmful than inbreeding depression or if females gain inclusive fitness benefits by mating with close kin. Here, we investigated genetic compatibility and mating patterns in an insular population of house sparrow (Passer domesticus), over a three-year period, using 12 microsatellite markers and one major histocompability complex (MHC) class I gene. Given the small population size and the distance from the mainland, we expected a reduced gene flow in this insular population and we predicted that females would show mating preferences for genetically dissimilar mates.

Results

Contrary to our expectation, we found that offspring were less genetically diverse (multi-locus heterozygosity) than expected under a random mating, suggesting that females tended to mate with genetically similar males. We found high levels of extra-pair paternity, and offspring sired by extra-pair males had a better fledging success than those sired by the social male. Again, unexpectedly, females tended to be more closely related to extra-pair mates than to their social mates. Our results did not depend on the type of genetic marker used, since microsatellites and MHC genes provided similar results, and we found only little evidence for MHC-dependent mating patterns.

Conclusions

These results are in agreement with the idea that mating with genetically similar mates can either avoid the disruption of co-adapted genes or confer a benefit in terms of kin selection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The adaptive function of mate choice remains unclear and one of the most challenging problems in behavioural ecology [1–3]. Choosy females can potentially obtain direct or indirect genetic benefits for their progeny (genetic quality or compatibility) [3–5]. Females that avoid mating with related or genetically similar mates avoid the costs of inbreeding depression [6–10]. Inbreeding avoidance may also increase the genetic diversity of progeny, which might confer fitness benefits in temporally and spatially heterogeneous environments. Yet, several recent studies have surprisingly reported evidence for mate choice for genetically related reproductive partners [11–13]. It is unclear whether or how inbreeding per se could be beneficial, though such findings may be due to outbreeding avoidance. If local environmental conditions selectively favour co-adapted ensembles of genes, mating with genetically distant partners could disrupt these assemblages and result in a loss of fitness (outbreeding depression) [14–17]. Bateson [18, 19] suggested that maximal reproductive success may be achieved by pairs with intermediate genetic relatedness, and there is support for his ‘optimal outbreeding’ hypothesis [20–22]. Mating preferences for kin could also allow females to increase their inclusive fitness [23–25] in the absence of significant inbreeding depression [18, 26, 27]. Similarly, selecting kin as social mates may improve cooperation between the sexes and reduce sexual conflict over parental investment [28].

The rapid development of molecular genetic tools in recent years has considerably aided mate choice research in several ways. First, although the vast majority of bird species are socially monogamous, many species also engage in extra-pair copulations so that broods are usually composed of chicks sired by different fathers [29–32]. Genetic paternity analyses allow the detection of extra-pair (EP) paternity and identification of EP males and EP offspring. Moreover, extra-pair mating presents an opportunity to examine the processes governing mate choice in the absence of any potential direct benefit since the extra-pair male does not contribute to parental care. According to the inbreeding avoidance hypothesis, for example, females mated with closely related males should engage in extra-pair copulations with genetically dissimilar mates [3], whereas the outbreeding avoidance and the kin selection hypotheses predict that females should engage in extra-pair copulations with genetically similar males [8, 33]. Second, molecular genetic tools make it possible to infer individuals’ genome-wide diversity and relatedness between partners using both neutral loci (e.g. microsatellites) and functional selected genes [1–5]. Third, molecular tools have helped to test the hypothesis that genetic benefits from mate choice include increasing offspring heterozygosity at the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) loci [34–39]. MHC genes encode cell-surface glycoproteins that control antigen presentation, and MHC heterozygotes are supposed to better face infectious diseases [40, 41]. Yet, just as different species show inbreeding or outbreeding preferences, recent work indicates the MHC-dependent mating preferences can be disassortative or assortative for alleles, disassortative for allelic diversity, or for specific alleles. It has been suggested that ‘if there is an optimal level of MHC heterozygosity for combating infections, then females should prefer to mate with males that have intermediate levels of MHC dissimilarity’ [35], and subsequent work has provide evidence that female preferences depend on males’ individual allelic diversity [39, 42, 43].

We studied mate choice both for social and extra-pair mates in a small insular population of the house sparrow (Passer domesticus), using microsatellite loci and MHC class I genes, over three consecutive years. Mating patterns were assessed by examining offspring genetic diversity. This indirect assessment only allowed us to infer realized mate choice, whereas assessing female preference would have required letting females choose a partner in the absence of constraints [44]. Given the small population size and the isolated nature of the studied population, we expected reduced gene flow. This led us to predict that females should preferentially mate with diverse and genetically dissimilar males to i) reduce the risk of inbreeding; ii) enhance genetic diversity of their progeny.

Methods

The study population

The house sparrow population studied here is located at Hoëdic, a small (2.08 km2) island off the French coast of Brittany (47°20’24.40”N-2°52’43.09”W). Adult house sparrows were captured using mist nets and banded with a metal ring and a unique combination of coloured rings which allowed individual recognition. At the first capture, we obtained a small amount of blood (20 μl) by brachial vein puncture and stored it in 500 μl of Queen’s Lysis Buffer (QLB) [45]. We monitored pairs breeding in nest boxes that were set up in the village, from 2009 to 2011. For logistic reasons, we were only able to monitor the first two broods during each year, even though house sparrows can lay up to 3-4 clutches per breeding season. Between late April and the end of June, we visited nest boxes at least twice per week and recorded clutch size and the number of hatched and fledged chicks. When chicks were 8 days old, they were banded with a metal ring and a drop of blood was collected and stored as for adults. The identities of social parents were assessed during focal observations when adults were brooding or feeding the chicks. Sample sizes are summarized in Table 1. Ringing licence and permit to take blood samples were given by the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (Paris) and the Préfecture du Morbihan.

We estimated population size using the POPAN module of the software MARK [46]. POPAN gives an estimate of the population size while taking into account the probabilities of recapture (p) and survival (ϕ), as well as the probability of new individuals entering the population (pent). We ran models where each of the three parameters was either constant or varied as a function of capture session (time) (three sessions per year, three years = nine capture sessions). The best model was selected based on the AIC criterion and was the model where the three parameters varied with time. We also used the U-CARE module to check any violation of the assumptions underlying the use of capture-mark-recapture models and did not find any departure from these assumptions [47].

Microsatellite genotyping

DNA was extracted using the Wizard® SV 96 Genomic DNA Purification kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All individuals were genotyped using the following twelve microsatellite loci: PdomD09, PdomA08, PdomB01, PdomH05 [48], Mjg1 [49], Ase18 [50], Pdo3, Pdo5 [51], Pdo1 [52], Pdo10 [53], Pdo16 and Pdo27 [54]. Polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed in a final volume of 10 μl including 10 to 50 ng of DNA, 2 μl of 5X buffer, 1.5 to 2 mM of MgCl2, 400 μl of dNTPs, 1 μM of each primers and 0,2 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega). The PCR program comprised: 94°C 3 to 4 min, 30 to 35 cycles of 94°C 20s, 20s for annealing (48°C to 62°C according to the different loci), and 72°C 30 to 40s, followed by a final extension of 72°C 5 to 7 min. Samples were then run in an ABI3730 automated sequencer. Allele sizes were determinated using GeneMapper v4.0.

MHC class I genotyping

We amplified the MHC class I exon 3, which corresponds to the highly variable peptide-binding region (PBR) of the protein [55]. Passerines have been shown to have several loci at the MHC class I exon 3 due to gene duplication and fragmentation, which makes it impossible to determine the number of amplified loci or estimate heterozygosity at each locus [42, 55–58].

PCR amplifications were performed using a fluorescent (6’FAM) labelled primer (A23M – GCG CTC CAG CTC CTT CTG CCC ATA) and an unlabeled primer (A21M – GTA CAG CGC CTT GTT GGC TGT GA). PCRs were performed in a final volume of 10 μl, including 50 to 100 ng of genomic DNA, 0.6 μM of each primer and 5 μl of Multiplex PCR reagent (QIAGEN GmbH) containing hot-start DNA polymerase, buffer and dNTPs. The PCR program began with 5min initial denaturation at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of 30s denaturation at 94°C, 90s annealing at 56°C and 90s extension at 72°C. A final elongation step was run for 10 min at 72°C. To control for PCR artefacts, we used 2 negative controls, for PCR and for sequencer, by adding purified water instead of DNA or PCR products. MHC diversity was screened using capillary electrophoresis single conformation polymorphism (CE-SSCP) [43]. PCR samples were prepared for electrophoresis by combining 1 μl PCR product, with 8.75 μl Hi-Di formamide and 0.25 μl of in-house prepared ROX size standard [59]. This mix was heated for 5min at 95°C to separate the complementary DNA strands. Electrophoresis was conducted in an automated DNA sequencer (ABI PRISM 3130 xl automated DNA Sequencer, Applied Biosystems). The retention time of allelic variants was assessed relative to the ROX size standard.

Statistical analyses

Estimations of within-individual genetic diversity and between-individual dissimilarity

Genome-wide inbreeding was assessed with individual Internal Relatedness (IR, [60]). IR corresponds to the number of homozygous loci, divided by the number of genotyped loci, weighted by the allele frequencies. To measure the genetic similarity between paired males and females, we also computed unbiased pairwise relatedness (r, [61]), where each locus is weighted using the method described in [62, 63]. IR and r were assessed from multilocus microsatellite genotypes.

Allele-sharing was calculated to estimate MHC similarity between males and females forming a pair-bond. Allele-sharing is twice the number of shared alleles divided by the number of different alleles of each individual [D = 2Fab/(Fa + Fb)] [42, 64].

Paternity analysis

In each nest, social parents were identified during the brooding and chick feeding period. To assess extra-pair paternity, we used the likelihood-based approach implemented in the software CERVUS 3.0 [65]. The software allows excluding and assigning putative fathers based on their multi locus genotypes. The probability of exclusion and assignment was fixed to 95%. We also tested if there was any mismatch between the maternal identity based on the field observations and the one based on microsatellites. Maternal mismatches would indicate that brood parasitism had occurred. Over the entire study period, in only two instances we found a mismatch between the maternal identity based on the field observations and the genetic markers. However, these mismatches involved complete clutches which likely reflect errors in the reading of the color bands rather than brood parasitism. Accordingly these two records were excluded from the statistical analyses. We considered a chick as being extra-pair if it was sired by a male other than the social male that was identified by field observations. We also tested whether there was any evidence suggesting a departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium of the microsatellite loci using CERVUS 3.0 [65]. We did not find any departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (all p < 0.05; Table 2).

Mate choice

The null hypothesis of random mating with respect to parental relatedness was tested by comparing observed chick IR values to expected distributions under this null hypothesis. We computed observed IRs for i) the overall sample of chicks produced over the three-year study period (n = 222), ii) chicks produced by social males (n = 111), and iii) chicks produced by extra-pair males (n = 65). Over the entire sample of 222 chicks, paternal identity could not be assigned for 46 chicks. We also compared the relatedness (r) between pair members (between the female and her social mate, and her genetic mate when she engaged in EP copulations) to the expected distribution of values under random mating. Expected values were generated using the software STORM [66] by randomly sampling (1000 iterations for each year) reproductive males and females that were observed in a given year in order to generate the same number of chicks and mating pairs to the observed ones in the same year.

MHC allele-sharing (D, between the female and her social mate, and her genetic mate when she engaged in EP copulations) was compared with the distribution of expected D values obtained by randomly generating mating pairs (1000 bootstraps for each year, R version 2.15.0, R Development Core Team 2011). As for IR and r, D was computed using social and extra-pair partners.

Hypothesis testing

We used General Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) to test the hypothesis that females mated with more closely related social males would also engage in extra-pair fertilization. Brood type was modeled as a binary response variable (with or without extra-pair chicks). The explanatory (fixed) variables were social male IR, relatedness to the female (r), band-sharing within the male-female pair, and year. Since some females laid several clutches during the three-year period covered by the study, female identity nested within year was set as a random factor.

We also compared the hatching and fledging success of broods with no extra-pair chicks to the hatching and fledging success of broods containing at least one extra-pair young. Here, fledging success was entered as a binomial response variable (fledged or not), year and brood type (broods with extra-pair or no extra-pair young) were also included as fixed factors and female identity was nested within year as a random factor.

Internal Relatedness (IR) of chicks produced by social males was compared to IR of chicks produced by extra-pair males using a GLMM with a binomial distribution of errors. Year, chick type (sired by the social or the extra-pair male), and their interactions were added as fixed factors. Female identity was nested within year and entered as a random factor.

We also compared IR, r and D between social and extra-pair males, for the restricted sample of females that engaged in extra-pair copulations, with the aim of investigating if male genetic characteristics and the relatedness with the female affected the likelihood of being a social or an extra-pair male. We constructed a GLMM where male status (social or extra-pair) was entered as a binomial response variable. Male IR, D, r and year were included as fixed factors. Breeding event nested within female and within year was also declared as a random factor. When a female mated with several extra-pair mates during a single reproductive event, we computed the mean IR, r and D and used these values in the statistical models.

We used a similar GLMM to test if within-brood chicks sired by the social or the extra-pair male(s) differed in their fledging success. Fledging success corresponds to the number of fledged chicks sired by a given male, divided by the total number of eggs laid and this was modeled as a binomial response variable. Male type (social or extra-pair), year and their interaction were added as fixed factors. Breeding event, nested within female identity and year was added as a random factor.

We used the package lme4 [67], implemented in R 2.15.0 to run all GLMMs. We used the information-theoretic (IT) approach to perform model selection [68]. Model support was assessed using the corrected version of Akaike Information Criterion (AICc) for small sample sizes, and ΔAIC was used to infer support for models in the candidate set [69]. ΔAIC corresponds to the difference in AICc of the focus model minus the AICc of the best model (the model with the lowest AIC) [68]. We calculated the Akaike weights (ω) for each model, which is the probability that a model is selected as the best in a model set [68]. Using the package MuMIn [70], we also calculated the summed AIC weight (ΣAICω) for each variable. This corresponds to the sum of the weights of the models in which the variable is present and can be interpreted as the probability that a given variable is retained in the selected model [68, 71]. Following Burnham and Anderson [68], we considered that a model had substantial empirical support if its ΔAIC was lower than 2.

Results and discussion

The number of alleles for each microsatellite locus varied between 8 and 21, whereas observed heterozygosity varied between 0.70 and 0.91 (Table 2). Individuals had a mean of 21.50 (± 1.05 SE) microsatellite alleles over 12 loci, and a mean of 2.31 (± 0.05 SE) MHC class I alleles. The individual MHC allele number varied between 1 and 6 (from as many as 3 class I loci amplified) and a total of 37 MHC alleles were found in the entire population.

Over the three study years the average population size of adult birds was 204 individuals (± 21 SE). Therefore, we sampled a substantial fraction of the total estimated breeding population each year.

In 2009, 2010 and 2011, respectively 35.3, 40.2 and 48.3% of chicks were from extra-pair matings. Similarly, 64.3, 57.7 and 69.0% of broods contained at least one extra-pair young, respectively.

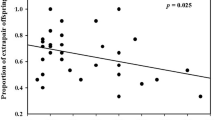

The observed IR computed over the entire sample of chicks (IRobs) was significantly higher than expected under random mate choice (mean = 0.037 ± 0.001 SE; n = 222; p = 0.020; Figure 1A). The results were similar when IR was computed on within-pair only (IRobswithin-pair = 0.032 ± 0.014 SE; p = 0.046; n = 112), or extra-pair only chicks (IRobsextra-pair = 0.044 ± 0.020 SE; p = 0.009; n = 53) (Figure 1A).

Distribution of the 1,000 bootstraped Internal Relatedness IR (A), pairwise-relatedness r (B) and MHC allele-sharing (C). IRobs, IRobswithin-pair and IRobsextra-pair correspond to the observed IR computed on the entire sample of chicks, chicks produced by social males and chicks produced by extra-pair males, respectively. robssocial, Dobssocial correspond to the observed r and allele-sharing between the female and her social mate. robsgenetic, Dobsgenetic corresponds to the observed r and allele-sharing between the female and her extra-pair mate.

Mean pairwise relatedness (robssocial) between females and their social mates was -0.008 (± 0.016 SE; n = 96) and did not differ from expected values under a random mate choice (Figure 1B). Mean pairwise relatedness (robsgenetic) between females and their genetic mates was 0.011 (± 0.018 SE; n = 79) and did not differ from expected values under random mate choice (Figure 1B).

MHC allele-sharing (Dobssocial) between females and their social mates and allele-sharing (Dobsgenetic) between females and their extra-pair mates where respectively 0.263 (± 0.024 SE; n = 56) and 0.333 (± 0.045 SE; n = 75), and did not differ from expected values under random mate choice (Figure 1C).

None of the measures of relatedness between the female and her social mate (r), and inbreeding level of the male (IR) affected the female likelihood to engage in extra-pair fertilizations, since the model with the lowest AIC value was the null model (Table 3, n = 70). Similarly, none of the variables improved the fit of the model exploring the variation in hatching success (the null model had the lowest AIC and the highest ω (Table 4, n = 61). However, fledging success did vary among years (0.89 in 2009, 0.75 in 2010, and 0.59 in 2011) and the model including year had the lowest AIC and the highest ω values (Table 4, n = 53). IR of chicks was not influenced by mating type (social or extra-pair) but tended to vary across years. However, we should note that the null model is very close suggesting that the effect of year is rather weak (Table 5, n = 222).

We then focused on broods that contained both within and extra-pair chicks to compare the genetic characteristics (IR, r and D) between social and extra-pair mates. The best model was the one that included pairwise relatedness (r, Table 6, n = 60). The ΔAICc and ΣAICω of the other competitive models also suggested a possible role for MHC band sharing and pairwise relatedness (Table 6). The mean pairwise relatedness was 0.074 (± 0.029 SE, n = 30) between females and extra-pair mates whereas it was 0.008 (± 0.029 SE, n = 30) between females and social mates. MHC allele-sharing was 0.34 (± 0.050 SE, n = 30) between females and extra-pair mates, and 0.24 (± 0.047 SE, n = 30) between females and social mates. We should however mention that the null model is also competitive suggesting that the contribution of these variables is weak.

Fledging success of chicks sired by extra-pair males (0.41 ± 0.047 SE, n = 30) was higher than for chicks sired by the social mate (0.20 ± 0.044 SE, n = 30). The model including sire type (social vs. extra-pair) had the lowest AIC (Table 7, n = 60), and sire type had a very high ΣAICω (0.99).

We expected that the particular demographic and ecological characteristics of the studied insular population of house sparrows would have promoted the evolution of mating preference for dissimilar mates to avoid the depletion of genetic diversity and inbreeding [6–13, 72]; however, our results do not provide support for the “inbreeding avoidance” hypothesis. On the contrary, we found evidence suggesting a preference for genetically similar mates. Over the three years covered by the study, we found that offspring were less heterozygous than expected under random mate choice (based on 12 microsatellite loci), though there was little support that MHC class I genes influenced pair formation. This pattern was consistent even when taking into account the relatively high proportion of extra-pair fertilizations. When focusing on broods containing both within and extra-pair chicks, we also found that extra-pair mates tended to be genetically more similar to the females than social mates both for microsatellite markers and MHC genes, even though the statistical support for these findings was less clear-cut than for offspring heterozygosity. Interestingly, in broods containing both within- and extra-pair young, fledging success of chicks sired by extra-pair males was higher than for chicks sired by social mates.

We could only assess realized mate choice (actual mating patterns) and not female preference (the preference that females might express in the absence of constraints). A number of environmental constraints might prevent females from expressing their actual preferences. For example, imperfect sampling of potential mates or the cost of mate searching can indeed affect the pattern of realized mate choice [44].

Our prediction that females would tend to mate with genetically dissimilar mates was based on the assumption that this insular population has low genetic diversity and that it is therefore vulnerable to inbreeding depression. However, as a part of a larger study on the population genetics of the house sparrow, we found that the within-population diversity of both microsatellites and MHC was similar between this (Hoëdic) and six mainland populations located within a radius of 200 km (Bichet et al., unpublished observations). The Hoëdic population was nevertheless genetically differentiated (based on Fst values) from the other populations used in this study. Therefore, while genetic variation has been maintained in this insular population, isolation and reduced gene flow have still produced genetic divergence from the mainland populations (Bichet et al., unpublished observations).

Insofar as the elevated IR of both intra- and extra-pair offspring reflects a female mating preference for genetically similar males (but see findings on pairwise relatedness between mates, Figure 1B), there are several possible mechanisms that could explain such a preference. First, spatially variable environmental conditions (such as variable risks to contract infectious diseases) might have promoted the evolution of co-adapted genes conferring a benefit under the locally prevailing conditions. Second, preference for genetically similar mates might also evolve through kin selection where females seek to increase their own inclusive fitness [23, 25]. Our finding that females engaging in extra-pair matings showed a preference for more genetically similar males is also in agreement with the results of two recent avian studies on ground tits (Parus humilis) [13] and barn swallows (Hirundo rustica) [33]. Wang and Lu [13] showed that even though the propensity of females to engage in extra-pair matings did not depend on the relatedness with the social mates, females nevertheless sought extra-pair copulations with males with whom they were more related to than their social mates. Since there was no cost due to mating with relatives, Wang and Lu [13] suggested that these results support the hypothesis that females gain inclusive fitness by mating with related males.

Findings based on offspring heterozygosity (IR) and based on relatedness between pair members (r) provided a quite different picture, which might appear puzzling. One possible explanation involves the residual variation in IR that is not accounted for by r. Alternatively, we would also like to remind that the two indices refer to two different steps in the process of mate choice, r refers to the similarity between mates, IR refers to the product of the mate choice where recombination, early embryo failure, etc. might contribute to generate the observed discrepancy.

Population structure or ‘environmental constraints’ might also affect pair formation potentially interfering with mating preferences [44]. For instance, related individuals might tend to cluster in the same flock, as reported for instance in lekking peacocks (Pavo cristatus) [73] and to occupy nearby nest boxes, which might increase the likelihood of mating with genetically similar mates. However, since the relatedness between social mates was not higher than for random pairs, this type of clustering seems unlikely in the present case.

A large proportion of chicks were sired by an extra-pair mate. The proportion of extra-pair chicks was higher than those previously reported for other house sparrow populations [51, 74–77]. One possible explanation is a bias in estimates of extra-pair chicks due to mistaken identification of birds (coloured leg bands), however, this is unlikely as we found a mismatch in maternal identity in only 3% (2/69) of broods (and in both cases the entire brood was assigned to a single mother). In five broods, none of the chicks was assigned to the social father. However, in all of these five cases, chicks were assigned to at least two different males, strongly suggesting that the high proportion of extra-pair chicks was not the result of mistakes in the identification of the social father. Most of the previous work found that extra-pair paternity is low in insular populations [12, 51, 78], although some exceptions have been reported [79–81], with as much as 55% of extra-pair chicks reported for an insular population of tree swallows (Tachycineta bicolor) [75]. The ecological factors that might explain why insular populations have lower or higher levels of extra-pair paternity compared to mainland populations are unclear and contentious. One might speculate that insular populations with high breeding density and synchrony might be more prone to extra-pair copulations because of the increased availability of extra-pair mates, but this would require additional work.

There have been extensive reports of MHC-dependent mating preferences [9, 39, 82–88]; however, we found no support for a potential role of MHC genes in mate choice, other than the general assessment of relatedness. Insular populations might be less exposed to parasites and pathogens [89–92], which could weaken the selection for specific MHC alleles and diversity (but see [9]).

Conclusions

These results tend to support the idea that mating with genetically similar mates can either avoid the disruption of co-adapted genes or confer a benefit in terms of kin selection. Definitely, more work should be devoted to the role of MHC-based mate choice in mainland and insular populations that differ in their exposure to infectious diseases.

Abbreviations

- MHC:

-

Major Histocompatibility Complex

- EP:

-

Extra-pair

- PBR:

-

Peptide-binding region

- IR:

-

Internal relatedness

- IRobs:

-

Observed internal relatedness

- IRobsextra-pair:

-

Observed internal relatedness for extra-pair chicks

- IRobswithin-pair:

-

Observed internal relatedness for within-pair chick

- MLH:

-

Multi-locus heterozygosity

- r:

-

Pairwise relatedness

- robssocial:

-

Observed pairwise relatedness for social pairs, between the female and her social male

- robsgenetic:

-

Observed pairwise relatedness for genetic pairs, between the female and the male who sired the chicks

- D:

-

Number of shared MHC alleles

- Dobssocial:

-

Observed number of shared MHC alleles for social pairs

- Dobsgenetic:

-

Observed number of shared MHC alleles for genetic pairs

- GLMM:

-

General Linear Mixed Model

- AIC:

-

Akaike Information Criterion

- ω:

-

AIC weights

- ∑AICω:

-

Summed AIC weights.

References

Andersson MB: Sexual Selection. 1994, New Jersey: Princeton University Press

Clutton-Brock T: Sexual selection in males and females. Science. 2007, 318: 1882-1885. 10.1126/science.1133311.

Kempenaers B: Mate choice and genetic quality: a review of the heterozygosity theory. Advances in the Study of Behavior, Vol 37. 2007, San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press Inc, 189-278. Advances in the Study of Behavior

Neff BD, Pitcher TE: Genetic quality and sexual selection: an integrated framework for good genes and compatible genes. Mol Ecol. 2005, 14: 19-38.

Mays HL, Albrecht T, Liu M, Hill GE: Female choice for genetic complementarity in birds: a review. Genetica. 2008, 134: 147-158. 10.1007/s10709-007-9219-5.

Mays HL, Hill GE: Choosing mates: good genes versus genes that are a good fit. Trends Ecol Evol. 2004, 19: 554-559. 10.1016/j.tree.2004.07.018.

Tregenza T, Wedell N: Genetic compatibility, mate choice and patterns of parentage: invited review. Mol Ecol. 2000, 9: 1013-1027. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.00964.x.

Ferretti V, Massoni V, Bulit F, Winkler DW, Lovette IJ: Heterozygosity and fitness benefits of extrapair mate choice in White-rumped Swallows (Tachycineta leucorrhoa). Behav Ecol. 2011, 22: 1178-1186. 10.1093/beheco/arr103.

Richardson DS, Komdeur J, Burke T, von Schantz T: MHC-based patterns of social and extra-pair mate choice in the Seychelles warbler. Proc Royal Soc B-Biolog Sci. 2005, 272: 759-767. 10.1098/rspb.2004.3028.

Charlesworth D, Willis JH: Fundamental concepts in genetics. The genetics of inbreeding depression. Nat Rev Genet. 2009, 10: 783-796. 10.1038/nrg2664.

Cohen LB, Dearborn DC: Great frigatebirds, Fregata minor, choose mates that are genetically similar. Anim Behav. 2004, 68: 1229-1236. 10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.12.021.

Krokene C, Lifjeld JT: Variation in the frequency of extra-pair paternity in birds: a comparison of an island and a mainland population of blue tits. Behaviour. 2000, 137: 1317-1330. 10.1163/156853900501944.

Wang C, Lu X: Female ground tits prefer relatives as extra-pair partners: driven by kin-selection?. Mol Ecol. 2011, 20: 2851-2863. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05070.x.

Shields WM: The natural and unnatural history of inbreeding and outbreeding. The Natural and Unnatural History of Inbreeding and Outbreeding: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives. Edited by: Thornhill NW. 1993, Chicago: Chicago University Press, 143-169.

Waller NM: The statics and dynamics of mating system evolution. The Natural and Unnatural History of Inbreeding and Outbreeding: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives. Edited by: Thornhill NW. 1993, Chicago: Chicago University Press, 97-117.

Frankham R, Ballou JD, Eldridge MDB, Lacy RC, Ralls K, Dudash MR, Fenster CB: Predicting the probability of outbreeding depression. Conserv Biol. 2011, 25: 465-475. 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2011.01662.x.

Puurtinen M: Mate choice for optimal (K) inbreeding. Evolution. 2011, 65: 1501-1505. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01217.x.

Bateson P: Sexual imprinting and optimal outbreeding. Nature. 1978, 273: 659-660. 10.1038/273659a0.

Bateson P: Optimal outbreeding. Mate Choice. Edited by: Bateson P. 1983, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 257-277.

Dolgin ES, Charlesworth B, Baird SE, Cutter AD: Inbreeding and outbreeding depression in Caenorhabditis nematodes. Evolution. 2007, 61: 1339-1352. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00118.x.

Ryder TB, Tori WP, Blake JG, Loiselle BA, Parker PG: Mate choice for genetic quality: a test of the heterozygosity and compatibility hypotheses in a lek-breeding bird. Behav Ecol. 2010, 21: 203-210. 10.1093/beheco/arp176.

Sherman CDH, Wapstra E, Uller T, Olsson M: Males with high genetic similarity to females sire more offspring in sperm competition in Peron’s tree frog Litoria peronii. Proc Royal Soc B-Biolog Sci. 2008, 275: 971-978. 10.1098/rspb.2007.1626.

Kokko H, Ots I: When not to avoid inbreeding. Evolution. 2006, 60: 467-475.

Oh KP: Inclusive fitness of ‘kissing cousins’: new evidence of a role for kin selection in the evolution of extra-pair mating in birds. Mol Ecol. 2011, 20: 2657-2659. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05118.x.

Waser PM, Austad SN, Keane B: When should animals tolerate inbreeding. Am Nat. 1986, 128: 529-537. 10.1086/284585.

Lehmann L, Perrin N: Inbreeding avoidance through kin recognition: choosy females boost male dispersal. Am Nat. 2003, 162: 638-652. 10.1086/378823.

Parker GA: Sexual conflict over mating and fertilization: an overview. Philos Transac Royal Soc B-Biolog Sci. 2006, 361: 235-259. 10.1098/rstb.2005.1785.

Thunken T, Bakker TCM, Baldauf SA, Kullmann H: Active inbreeding in a cichlid fish and its adaptive significance. Curr Biol. 2007, 17: 225-229. 10.1016/j.cub.2006.11.053.

Cockburn A: Prevalence of different modes of parental care in birds. Proc Royal Soc B-Biolog Sci. 2006, 273: 1375-1383. 10.1098/rspb.2005.3458.

Lack D: Ecological Adaptations for Breeding in Birds. 1968, London: Methuen

Griffith SC, Owens IPF, Thuman KA: Extra pair paternity in birds: a review of interspecific variation and adaptive function. Mol Ecol. 2002, 11: 2195-2212.

Moller AP, Ninni P: Sperm competition and sexual selection: a meta-analysis of paternity studies of birds. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1998, 43: 345-358. 10.1007/s002650050501.

Kleven O, Jacobsen F, Robertson RJ, Lifjeld JT: Extrapair mating between relatives in the barn swallow: a role for kin selection?. Biol Lett. 2005, 1: 389-392. 10.1098/rsbl.2005.0376.

Apanius V, Penn D, Slev PR, Ruff LR, Potts WK: The nature of selection on the major histocompatibility complex. Crit Rev Immunol. 1997, 17: 179-224. 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v17.i2.40.

Penn DJ, Potts WK: The evolution of mating preferences and major histocompatibility complex genes. Am Nat. 1999, 153: 145-164. 10.1086/303166.

Milinski M: The major histocompatibility complex, sexual selection, and mate choice. Annual Review of Ecology Evolution and Systematics. Volume 37. 2006, Palo Alto: Annual Reviews, 159-186. Annual Review of Ecology Evolution and Systematics

Piertney SB, Oliver MK: The evolutionary ecology of the major histocompatibility complex. Heredity. 2006, 96: 7-21.

Landry C, Garant D, Duchesne P, Bernatchez L: ‘Good genes as heterozygosity’: the major histocompatibility complex and mate choice in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Proc Royal Soc B-Biolog Sci. 2001, 268: 1279-1285. 10.1098/rspb.2001.1659.

Reusch TBH, Haberli MA, Aeschlimann PB, Milinski M: Female sticklebacks count alleles in a strategy of sexual selection explaining MHC polymorphism. Nature. 2001, 414: 300-302. 10.1038/35104547.

Penn DJ: The scent of genetic compatibility: Sexual selection and the major histocompatibility complex. Ethology. 2002, 108: 1-21. 10.1046/j.1439-0310.2002.00768.x.

Penn DJ, Damjanovich K, Potts WK: MHC heterozygosity confers a selective advantage against multiple-strain infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002, 99: 11260-11264. 10.1073/pnas.162006499.

Bonneaud C, Chastel O, Federici P, Westerdahl H, Sorci G: Complex Mhc-based mate choice in a wild passerine. Proc Royal Soc B-Biolog Sci. 2006, 273: 1111-1116. 10.1098/rspb.2005.3325.

Griggio MGM, Biard C, Penn DJ, Hoi H: Female house sparrows “count on” male genes: experimental evidence for MHC-dependent mate preference in birds. Bmc Evol Biol. 2011, 11: 44-10.1186/1471-2148-11-44.

Wagner WE: Measuring female mating preferences. Anim Behav. 1998, 55: 1029-1042. 10.1006/anbe.1997.0635.

Seutin G, White BN, Boag PT: Preservation of avian blood and tissue samples for DNA analyses. Canad J Zool-Revue Canadienne De Zoologie. 1991, 69: 82-90. 10.1139/z91-013.

White GC, Burnham KP: Program MARK: survival estimation from populations of marked animals. Bird Study. 1999, 46: 120-139. 10.1080/00063659909477239.

Choquet R, Lebreton JD, Gimenez O, Reboulet AM, Pradel R: U-CARE: Utilities for performing goodness of fit tests and manipulating CApture-REcapture data. Ecography. 2009, 32: 1071-1074. 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2009.05968.x.

Garnier S, Durand P, Arnathau C, Risterucci AM, Esparza-Salas R, Cellier-Holzem E, Sorci G: New polymorphic microsatellite loci in the house sparrow, Passer domesticus. Mol Ecol Resour. 2009, 9: 1063-1065. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02552.x.

Li SH, Huang YJ, Brown JL: Isolation of tetranucleotide microsatellites from the Mexican jay Aphelocoma ultramarina. Mol Ecol. 1997, 6: 499-501. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.1997.00215.x.

Richardson DS, Jury FL, Dawson DA, Salgueiro P, Komdeur J, Burke T: Fifty Seychelles warbler (Acrocephalus sechellensis) microsatellite loci polymorphic in Sylviidae species and their cross-species amplification in other passerine birds. Mol Ecol. 2000, 9: 2226-2231.

Griffith SC, Stewart IRK, Dawson DA, Owens IPF, Burke T: Contrasting levels of extra-pair paternity in mainland and island populations of the house sparrow (Passer domesticus): is there an ‘island effect’?. Biol J Linn Soc. 1999, 68: 303-316.

Neumann K, Wetton JH: Highly polymorphic microsatellites in the house sparrow Passer domesticus. Mol Ecol. 1996, 5: 307-309. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.1996.00095.x.

Griffith SC, Dawson DA, Jensen H, Ockendon N, Greig C, Neumann K, Burke T: Fourteen polymorphic microsatellite loci characterized in the house sparrow Passer domesticus (Passeridae, Aves). Mol Ecol Notes. 2007, 7: 333-336.

Dawson DA, Horsburgh GJ, Kupper C, Stewart IRK, Ball AD, Durrant KL, Hansson B, Bacon I, Bird S, Klein A, Krupa AP, Lee J-W, Martin-Galvez D, Simeoni M, Smith G, Spurgin LG, Burke T: New methods to identify conserved microsatellite loci and develop primer sets of high cross-species utility - as demonstrated for birds. Mol Ecol Resour. 2010, 10: 475-494. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02775.x.

Bonneaud C, Sorci G, Morin V, Westerdahl H, Zoorob R, Wittzell H: Diversity of Mhc class I and IIB genes in house sparrows (Passer domesticus). Immunogenetics. 2004, 55: 855-865. 10.1007/s00251-004-0648-3.

Loiseau C, Richard M, Garnier S, Chastel O, Julliard R, Zoorob R, Sorci G: Diversifying selection on MHC class I in the house sparrow (Passer domesticus). Mol Ecol. 2009, 18: 1331-1340. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04105.x.

Loiseau C, Zoorob R, Robert A, Chastel O, Julliard R, Sorci G: Plasmodium relictum infection and MHC diversity in the house sparrow (Passer domesticus). Proc Biol Sci. 2011, 278: 1264-1272. 10.1098/rspb.2010.1968.

Balakrishnan CN, Ekblom R, Volker M, Westerdahl H, Godinez R, Kotkiewicz H, Burt DW, Graves T, Griffin DK, Warren WC, Edwards SV: Gene duplication and fragmentation in the zebra finch major histocompatibility complex. Bmc Biology. 2010, 8: 29-10.1186/1741-7007-8-29.

DeWoody JA, Schupp J, Kenefic L, Busch J, Murfitt L, Keim P: Universal method for producing ROX-labeled size standards suitable for automated genotyping. Biotechniques. 2004, 37: 348-

Amos W, Wilmer JW, Fullard K, Burg TM, Croxall JP, Bloch D, Coulson T: The influence of parental relatedness on reproductive success. Proc Roy Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001, 268: 2021-2027. 10.1098/rspb.2001.1751.

Li CC, Weeks DE, Chakravarti A: Similarity of DNA fingerprints due to chance and relatedness. Hum Hered. 1993, 43: 45-52. 10.1159/000154113.

Lynch M, Ritland K: Estimation of pairwise relatedness with molecular markers. Genetics. 1999, 152: 1753-1766.

Van de Casteele T, Galbusera P, Matthysen E: A comparison of microsatellite-based pairwise relatedness estimators. Mol Ecol. 2001, 10: 1539-1549. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2001.01288.x.

Wetton JH, Carter RE, Parkin DT, Walters D: Demographic-study of a wild house sparrow population by DNA fingerprinting. Nature. 1987, 327: 147-149. 10.1038/327147a0.

Kalinowski ST, Taper ML, Marshall TC: Revising how the computer program CERVUS accommodates genotyping error increases success in paternity assignment. Mol Ecol. 2007, 16: 1099-1106. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03089.x.

Frasier TR: STORM: software for testing hypotheses of relatedness and mating patterns. Mol Ecol Resour. 2008, 8: 1263-1266. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2008.02358.x.

Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B: lme4: linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. R package version 0.999375-42. 2011, http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4,

Burnham KP, Anderson DR: Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach. 2002, New York: Springer, 2

Bolker BM, Brooks ME, Clark CJ, Geange SW, Poulsen JR, Stevens MHH, White JSS: Generalized linear mixed models: a practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol Evol. 2009, 24: 127-135. 10.1016/j.tree.2008.10.008.

Barton K: MuMIn: Multi-model inference. R Package Version 1.7.2. edition. 2012, http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn,

Symonds MRE, Moussalli A: A brief guide to model selection, multimodel inference and model averaging in behavioural ecology using Akaike’s information criterion. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2011, 65: 13-21. 10.1007/s00265-010-1037-6.

Frankham R: Do island populations have less genetic variation than mainland populations?. Heredity. 1997, 78: 311-327. 10.1038/hdy.1997.46.

Petrie M, Krupa A, Burke T: Peacocks lek with relatives even in the absence of social and environmental cues. Nature. 1999, 401: 155-157. 10.1038/43651.

Stewart IRK, Hanschu RD, Burke T, Westneat DF: Tests of ecological, phenotypic, and genetic correlates of extra-pair paternity in the House Sparrow. Condor. 2006, 108: 399-413. 10.1650/0010-5422(2006)108[399:TOEPAG]2.0.CO;2.

Veiga JP, Boto L: Low frequency of extra-pair fertilisations in House Sparrows breeding at high density. J Avian Biol. 2000, 31: 237-244. 10.1034/j.1600-048X.2000.310215.x.

Cordero PJ, Wetton JH, Parkin DT: Extra-pair paternity and male badge size in the House Sparrow. J Avian Biol. 1999, 30: 97-102. 10.2307/3677248.

Whitekiller RR, Westneat DF, Schwagmeyer PL, Mock DW: Badge size and extra-pair fertilizations in the House Sparrow. Condor. 2000, 102: 342-348.

Griffith SC: High fidelity on islands: a comparative study of extrapair paternity in passerine birds. Behav Ecol. 2000, 11: 265-273. 10.1093/beheco/11.3.265.

Charmantier A, Blondel J: A contrast in extra-pair paternity levels on mainland and island populations of mediterranean blue tits. Ethology. 2003, 109: 351-363. 10.1046/j.1439-0310.2003.00880.x.

Conrad KF, Johnston PV, Crossman C, Kempenaers B, Robertson RJ, Wheelwright NT, Boag T: High levels of extra-pair paternity in an isolated, low-density, island population of tree swallows (Tachycineta bicolor). Mol Ecol. 2001, 10: 1301-1308. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2001.01263.x.

Fridolfsson AK, Gyllensten UB, Jakobsson S: Microsatellite markers for paternity testing in the willow warbler Phylloscopus trochilus: high frequency of extra-pair young in an island population. Hereditas. 1997, 126: 127-132.

Potts WK, Manning CJ, Wakeland EK: Matting patterns in seminatural populations of mice influenced by MHC genotype. Nature. 1991, 352: 619-621. 10.1038/352619a0.

Egid K, Brown JL: The major histocompatibility complex and female mating preferences in mice. Anim Behav. 1989, 38: 548-550. 10.1016/S0003-3472(89)80051-X.

Olsson M, Madsen T, Nordby J, Wapstra E, Ujvari B, Wittsell H: Major histocompatibility complex and mate choice in sand lizards. Proc Roy Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2003, 270: S254-S256. 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0079.

Ekblom R, Saether SA, Grahn M, Fiske P, Kalas JA, Hoglund J: Major histocompatibility complex variation and mate choice in a lekking bird, the great snipe (Gallinago media). Mol Ecol. 2004, 13: 3821-3828. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02361.x.

von Schantz T, Wittzell H, Goransson G, Grahn M: Mate choice, male condition-dependent ornamentation and MHC in the pheasant. Hereditas. 1997, 127: 133-140.

Freeman-Gallant CR, Meguerdichian M, Wheelwright NT, Sollecito SV: Social pairing and female mating fidelity predicted by restriction fragment length polymorphism similarity at the major histocompatibility complex in a songbird. Mol Ecol. 2003, 12: 3077-3083. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01968.x.

Westerdahl H: No evidence of an MHC-based female mating preference in great reed warblers. Mol Ecol. 2004, 13: 2465-2470. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02238.x.

Maitland K, Kyes S, Williams TN, Newbold CI: Genetic restriction of Plasmodium falciparum in an area of stable transmission: an example of island evolution?. Parasitology. 2000, 120: 335-343. 10.1017/S0031182099005612.

Moro D, Lawson MA, Hobbs RP, Thompson RCA: Pathogens of house mice on arid Boullanger Island and subantarctic Macquarie Island, Australia. J Wildl Dis. 2003, 39: 762-771. 10.7589/0090-3558-39.4.762.

Lenaghan S, Boback S, Sundermann C, Crim A, Hester L, Hill B, Tedin K: Comparison of parasitic infections of Boa constrictor from mainland Belize and the surrounding islands. ICOPA XI: Proceedings of the 11th International Congress of Parasitology. 2006, Bologna: Medimond S R L, 471-474.

Nieberding C, Morand S, Libois R, Michaux JR: Parasites and the island syndrome: the colonization of the western Mediterranean islands by Heligmosomoides polygyrus (Dujardin, 1845). J Biogeogr. 2006, 33: 1212-1222. 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01503.x.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the volunteers for their help in the field: J. Bailly, M. Brenier, S. Cornet, B. Faivre, V. Maicher, C. Petit, F. Spinnler, and S. Stradella. We are very grateful to M. Gillingham, F.-X. Dechaume-Moncharmont, H. Brandl, G. Munimanda, W. van Dongen, P. Vegh and J. White for their help during various stages of this work.

Financial support was provided by the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche and the Region Bourgogne to C.B. and G.S., and from the Austrian Academy of Sciences to D.J.P. and Y.M.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Study design: DJP, YM, GS. Data collection in the field: CB, EC-H, MB, SG, GS. Molecular genetic analyses: CB, MB. Statistical analyses: CB, LD. Manuscript writing: CB, DJP, YM, LD, SG, GS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bichet, C., Penn, D.J., Moodley, Y. et al. Females tend to prefer genetically similar mates in an island population of house sparrows. BMC Evol Biol 14, 47 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-14-47

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-14-47