Abstract

Background

Disentangling the roles of geography and ecology driving population divergence and distinguishing adaptive from neutral evolution at the molecular level have been common goals among evolutionary and conservation biologists. Using single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) multilocus genotypes for 31 sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) populations from the Kvichak River, Alaska, we assessed the relative roles of geography (discrete boundaries or continuous distance) and ecology (spawning habitat and timing) driving genetic divergence in this species at varying spatial scales within the drainage. We also evaluated two outlier detection methods to characterize candidate SNPs responding to environmental selection, emphasizing which mechanism(s) may maintain the genetic variation of outlier loci.

Results

For the entire drainage, Mantel tests suggested a greater role of geographic distance on population divergence than differences in spawn timing when each variable was correlated with pairwise genetic distances. Clustering and hierarchical analyses of molecular variance indicated that the largest genetic differentiation occurred between populations from distinct lakes or subdrainages. Within one population-rich lake, however, Mantel tests suggested a greater role of spawn timing than geographic distance on population divergence when each variable was correlated with pairwise genetic distances. Variable spawn timing among populations was linked to specific spawning habitats as revealed by principal coordinate analyses. We additionally identified two outlier SNPs located in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II that appeared robust to violations of demographic assumptions from an initial pool of eight candidates for selection.

Conclusions

First, our results suggest that geography and ecology have influenced genetic divergence between Alaskan sockeye salmon populations in a hierarchical manner depending on the spatial scale. Second, we found consistent evidence for diversifying selection in two loci located in the MHC class II by means of outlier detection methods; yet, alternative scenarios for the evolution of these loci were also evaluated. Both conclusions argue that historical contingency and contemporary adaptation have likely driven differentiation between Kvichak River sockeye salmon populations, as revealed by a suite of SNPs. Our findings highlight the need for conservation of complex population structure, because it provides resilience in the face of environmental change, both natural and anthropogenic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Disentangling the roles of geography and ecology driving population divergence and speciation has been a common goal among evolutionary biologists [1]. Several studies spanning diverse taxa suggest that the influence of these factors is often hierarchical: geography, landscape features, and vicariance may be important at larger spatial scales, whereas ecology and life history may be important at finer spatial scales (fishes: [2, 3]; birds: [4, 5]; mammals: [6]; plants: [7]). Hierarchical structure and divergence below the species level have key implications for conservation and the definition of evolutionary significant units [8]. For management applications, a hierarchical distribution of population-level diversity has been deemed critical for the resilience of commercially exploited species, which some authors have defined as biocomplexity [9–11]; hierarchical structure may also provide a strong buffer against interannual fluctuations in abundance or 'portfolio effect', therefore ensuring long-term sustainability of wild populations in an era of growing anthropogenic impacts [12].

Research on salmonid systems has greatly enhanced our understanding of hierarchical divergence; in fact, genetic variance is normally larger between salmon populations inhabiting different basins than between salmon populations from the same basin that differ in ecological attributes [2, 3, 13, 14]. This configuration is likely a result of historical contingency (e.g., postglacial recolonization) and contemporary evolution of life history types [2, 15]. Anadromous salmon populations are highly philopatric; adults return to their natal sites in freshwater to reproduce, thus promoting genetic isolation and local adaptation [16]. In particular, adult sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka, Walbaum 1792) spawn among tributaries, outlet rivers, beaches, and even glacial habitats [13, 14, 17] after typically spending 2 or 3 years in the ocean [18, 19]. A combination of natural and sexual selection appears to maintain phenotypic divergence between populations, but especially between those using different types of spawning habitats (e.g., beaches and tributaries: [20, 21]). In addition, the timing of spawning often differs systematically between habitat types, and the regularity in timing of migration and spawning is critical to the structure and conservation of populations [22–24].

Molecular tools have become instrumental for quantifying population divergence and reproductive isolation in applied evolutionary biology studies. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are now the marker of choice among many geneticists for addressing evolutionary questions [25–28]. The majority of studies using these abundant bi-allelic markers have hitherto focused on model organisms [26] with fewer applications to nonmodel taxa (but see [29–31]). Because SNPs can be linked to functional genes, it is important to determine which markers have been likely targets of selection, otherwise, estimates of gene flow may be compromised [32]. So-called 'genome scans' have enabled identification of putative markers under selection exhibiting larger or smaller estimates of divergence--often referred to as 'outliers'--than selectively neutral markers [33]. Outliers have been related to adaptive divergence in several studies [34–36]; nevertheless, demography and neutral processes can leave similar signatures to selection in the genome. Population bottlenecks or expansions can be mistaken for selective sweeps [33, 37]. Furthermore, recent models of hierarchical structure suggest that, when gene flow occurs predominantly within rather than between groups of demes, the number of outliers could be upwardly biased [38].

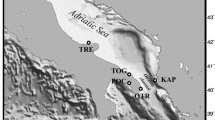

Here we employed multilocus genotypes from 42 nuclear and three mitochondrial SNPs isolated for sockeye salmon [39–41] to typify 31 spawning populations throughout the Kvichak River, which drains into Bristol Bay, southwest Alaska (Figure 1; Table 1). Our primary goal was to assess the differential roles of geography (e.g., discrete boundaries or continuous distance) and ecology (e.g., spawning habitat and timing) driving the spatial distribution of genetic diversity as revealed by SNPs. The Kvichak River is divided into two major subdrainages, each containing multiple lakes (Figure 1; Table 1). Subdrainages and lakes should represent natural landscape boundaries driving genetic diversity within and between O. nerka populations because (i) they were likely recolonized at varying times through different founding events as ice sheets sequentially retreated at the end of the Late Wisconsin glacial maximum (ca. 25,000 - 10,000 years BP: [42]); (ii) lakes provide nursery habitat for juvenile sockeye salmon growth, and also, an opportunity for strong olfactory imprinting, a crucial aid for adult homing behaviour [19]; and (iii) they may be isolated by the presence of waterfalls (Figure 1) that delay or deter upstream migration of returning adults, especially during years with increased river runoff [43, 44]. Lakes in turn harbour locally adapted populations that spawn among diverse environments, including mainland-beach, island-beach, and tributary habitats [45]. Some of these populations have discrete patterns of migration and spawn timing [23, 24], which adds a temporal dimension to spatial divergence [46]. Both ecological attributes--spawning habitat and timing of reproduction--predict that dispersal is most likely to occur between populations spawning in the same habitat, at the same time, or both, and this has found empirical support [21, 47–49]. Dispersal in salmonids may also follow an isolation-by-distance pattern if migration and drift have reached equilibrium [50], implying that gene flow is more efficient between nearby populations than those far apart [16]. We hypothesize that both geography and ecology should interact to influence large- (lake, subdrainages) and fine-scale dispersal (intralake) but we expected their importance to vary depending on the spatial scale: geographic attributes should be more important at larger scales, whereas ecological characteristics should be more important at finer scales.

Populations of sockeye salmon from the Kvichak River drainage. Location in southwest Alaska appears in rectangle of upper left insert. Numbers correspond to populations within Alagnak (1 - 9) and Kvichak (10 - 31) subdrainages. Population legends--tributaries: squares; mainland beaches: triangles; and island beaches: circles. Grey crosses indicate two waterfalls that may represent velocity barriers for migrating adults.

Our secondary goal was to evaluate the scope of neutral vs. adaptive differentiation in sockeye salmon as revealed by locus-specific estimates of divergence. Here we used two outlier detection methods to identify and characterize potential candidate SNPs responding to environmental selection, emphasizing which mechanism(s) may maintain the genetic variation of outlier loci. These analyses were conducted and reported first (see below) in order to avoid estimates of (neutral) divergence that may be biased by selection. Emphasis was placed on violations of the demographic assumptions of outlier detection models, including potential bottlenecks and hierarchical structure between populations [38, 51]. We subsequently conducted exploratory analyses of Hardy-Weinberg and linkage disequilibrium, estimated genetic diversity and differentiation, and tested for the relative effects of geography and ecology on population divergence, using SNP sets that included or excluded these outlier loci.

Results

Detection and characterization of outliers

BAYESCAN [51] suggested seven candidates for diversifying selection and one candidate for balancing selection (Table 2; Figure 2a). It quickly became apparent, though, that the majority of outlier SNPs were driven by a few divergent populations from Lake Clark (Figure 1; Table 1). When Lake Clark populations were removed, four loci no longer appeared as outliers (Figure 2b); their allele frequencies were very similar and showed strong differences (>0.5) only between Lake Clark and the rest of populations (e.g., One_HpaI-99: Figure 3a). Lake Clark populations further showed the lowest estimates of diversity within populations (see Results: Genetic diversity and differentiation), possibly indicating presence of bottlenecks. Marked allele frequency differences between subdrainages (~0.5) characterized other outliers, such as One_GPH-414 (Figure 3b) and One_STC-410 (not shown), suggesting that gene flow was more predominant within subdrainages than between subdrainages. Simulations in Arlequin 3.5 [52] confirmed that One_GPH-414 and One_STC-410 were no longer outliers assuming hierarchical structure between subdrainages (Figure 4). Therefore, only One _MHC2-190 and One_MHC2-251 consistently appeared to be under diversifying selection (Figure 2a-c; Figure 4).

Detection of outlier SNPs using BAYESCAN. Populations included in the analysis: (a) the entire Kvichak River drainage, (b) after excluding Lake Clark, and (c) Iliamna Lake only. FST: locus-specific genetic divergence among populations; log10Bayes Factor: decision factor in logarithmic scale (base 10) to determine selection; a vertical line indicates "decisive" evidence for selection. Filled circles represent candidates for selection; empty circles represent putatively neutral loci. Marker labels have been simplified (the prefix "One_" is missing).

Frequency plots of the major allele for four outlier SNPs in sockeye salmon. SNPs correspond to (a) One_HpaI-99, (b) One_GPH-414, (c) One_MHC2-190, and (d) One_MHC2-251 genotyped across 31 Alaskan populations (see Table 1 for population codes). Squares represent lakes from the Alagnak subdrainage (Battle: black; Kukaklek: grey; Nonvianuk: empty), whereas circles represent lakes from the Kvichak subdrainage (Clark: black; Sixmile: grey; Iliamna: empty).

Detection of outlier SNPs using Arlequin 3.5. Assuming a hierarchical model of migration and excluding Lake Clark populations. FST: locus-specific genetic divergence among populations; h0/(1 - FST): a modified measure of heterozygosity per locus. Dashed lines indicate lower and upper 95% confidence intervals for variation in neutral FST as a function of h0/(1 - FST). Filled circles represent candidates for selection; empty circles represent putatively neutral loci. Marker labels have been simplified (the prefix "One_" is missing).

Outlier SNPs were annotated to protein-encoding sequences with three exceptions (Table 2). Even though most mutations were intronic, One_MHC2-190 was located in exon β1 of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II which corresponded to a nonsynonymous substitution (aspartic acid to tyrosine) in the putative antigen recognition site [53]. Only 61 nucleotides separated this and the paired locus One_MHC2-251 located within an intervening intron [54]. Interestingly, allele frequencies appeared uncorrelated between One_MHC2-190 and One_MHC2-251 for some populations (Figure 3c-d); for instance, they fluctuated greatly between Sixmile Lake populations (1.0 to 0.01). Also, a group of populations from the east end of Iliamna Lake (16-Chinkelyes Creek, 20-Finger Beach, 23-Iliamna River, and 24-Knutson Beach) had much higher frequencies than the remaining populations for One_MHC2-251 (Figure 3d), but not One_MHC2-190 (Figure 3c).

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and linkage disequilibrium tests

No significant (p = 0.05) departures from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium were observed in any population or locus following exclusion of three mitochondrial SNPs (Table 1). However, we detected highly significant linkage disequilibrium for 3 nuclear locus-pairs across populations after a sequential Bonferroni correction for k tests (k = 703, p < 7.1 × 10-5): One_MHC2-190 (I = 0.433) and One_MHC2-251 (I = 0.465); One_Tf_ex10-7 (I = 0.632) and One_Tf_ex3-18 (I = 0.084); One_GPDH (I = 0.668) and One_GPDH2 (I = 0.082). Based on the information content per locus, I (Shannon-Weaver's index: in parentheses above), both One_MHC2-190 and One_MHC2-251 were kept for subsequent analyses, while One_Tf_ex3-18 and One_GPDH2 were excluded from further analyses. Exclusion of these loci decreased the pool of nuclear SNPs from 42 to 40.

Genetic diversity and differentiation

Estimates of SNP diversity and differentiation were obtained for three distinct nuclear sets of markers to account for possible effects of selection: 'No Outliers' or the putatively neutral set (38 SNPs: excluding One_MHC2-190 and One_MHC2-251), 'Outlier 1' (39 SNPs: including One_MHC2-190), and 'Outlier 2' (39 SNPs including One_MHC2-251). Differences between sets were emphasized if present; otherwise 'No Outliers' should be considered the default set.

Allelic richness (AR) ranged between 1.785 (3-Battle Lake River) and 1.979 (26-Nick Creek) and expected heterozygosity (HE) varied between 0.207 (13-Upper Tlikakila) and 0.264 (28-Upper Talarik Creek: Table 1). Both metrics were highly correlated across all populations (Spearman R = 0.733 p < 0.001). We also detected differences in AR (χ2 = 21.2, p < 0.001) and HE between lakes (χ2 = 21.5, p < 0.001). The lowest diversities were found within Clark and Battle, whereas the highest were in Sixmile and Iliamna (Table 3). Diversity contrasts between subdrainages (Alagnak vs. Kvichak) were also significant (AR: U = 22.5, p = 0.004; HE: U = 11.5, p = 0.012).

Estimates of global divergence were slightly higher for 'Outlier 1' (FST = 0.082; 95% CI: 0.047 - 0.123; p < 0.001) and 'Outlier 2' (FST = 0.080; 95% CI: 0.047 - 0.118; p < 0.001) than for the 'No Outliers' set (FST = 0.060; 95% CI: 0.041 - 0.095; p < 0.001). Pairwise FST for the entire drainage were significantly correlated between SNP sets based on simple Mantel tests and Pearson correlation coefficient, r ('No Outliers' vs. 'Outlier 1' r = 0.98, p < 0.001; 'No Outliers' vs. 'Outlier 2' r = 0.98, p < 0.001; 'Outlier 1' vs. 'Outlier 2' r = 0.97, p < 0.001). Global differentiation among mitochondrial SNPs was also highly significant (ΦPT = 0.054; p < 0.001) but lower than estimates found for nuclear SNPs.

Pairwise FST values were consistently significant between populations located in different lakes for all three SNP sets, even though multiple population comparisons within Iliamna Lake suggested no differentiation (see additional file 1). Notable examples included: (i) 1-Battle Lake Beach and 2-Battle Lake Tributary, two populations that spawn in contrasting habitats but are in close geographic proximity; (ii) 5-Moraine Creek and 6-Moraine Creek Early, and (iii) 7-Nanuktuk Creek and 8-Nanuktuk Creek Early, which may represent either two discrete populations migrating at different times or one large population with a protracted spawning period.

Effects of geography at large spatial scales (entire drainage)

Simple and partial Mantel tests suggested that geographic distance played a greater role than spawn timing influencing genetic distances for the entire drainage, albeit the effects of both variables were significant at this scale (Table 4). We also found strong evidence for hierarchical structure in both nuclear and mitochondrial SNPs through an analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA: see additional file 2); significance of variance components was found in all three SNP sets. Lakes harboured the highest percentage of genetic variance (6- to 13-times higher than between populations within lakes, depending on marker type), whereas subdrainage variance was similar to that found between populations within subdrainages. However, subdrainage structure became important after markedly differentiated Lake Clark populations were excluded. Yet, between-lake genetic variance was consistently higher than subdrainage variance, even when Lake Clark was excluded (additional file 2).

An unrooted neighbour-joining tree using Cavalli-Sforza & Edwards [55] chord distances revealed that spatial structure was largely driven by marked differences between populations inhabiting distinct lakes, followed by less pronounced differences between populations within lakes (Figure 5); this result was consistent with the hierarchical AMOVA. Within the Alagnak subdrainage, a long branch separated Nonvianuk Lake from the rest of the populations; for the Kvichak subdrainage, Lake Clark showed the longest branch indicative of strong reproductive isolation. Also, a tree R2 = 0.97 indicates that branch lengths explained a substantial amount of the variation present in the matrix of population distances [56].

Unrooted neighbour-joining tree between sockeye salmon populations. Based on Cavalli-Sforza & Edwards [51] chord distances for 38 nuclear ('No Outliers') SNPs. Segmented lines indicate the Alagnak (blue) and Kvichak (red) subdrainages; squares represent lakes from Alagnak (Battle: black; Kukaklek: grey; Nonvianuk: empty squares), whereas circles represent lakes from Kvichak (Clark: black; Sixmile: grey; Iliamna: empty). Numbers on branches represent percentages (only >50% are shown) of bootstrap support after generating 1000 resampled trees. R2 depicts how well branch length and the variation of the distance matrix are correlated.

Effects of ecology at fine spatial scales (Iliamna Lake)

Simple and partial Mantel tests performed within the population-rich Iliamna Lake suggested that spawn timing had a higher degree of correlation with pairwise genetic distances than geographic distances, albeit only for the 'Outlier 2' SNP set (Table 4). The effects of geography were still evident at this scale, however, despite the fact that they exhibited lower correlation values (Table 4).

Principal coordinate analyses (PCO) from pairwise FST within Iliamna Lake showed that spawning habitat explained a great extent of fine-scale clustering patterns (Figure 6a-c). Island beaches (21-Flat Island, 27-Triangle Island, and 29-Woody Island) comprised a genetically homogeneous group (all tests of differentiation: p > 0.1; see additional file 1) that was markedly distinct from populations spawning in tributaries and mainland beaches. Tributary spawners comprised a homogeneous cluster despite some exceptions, namely 16-Chinkelyes Creek (Figure 6c), 17-Copper River (Figure 6b) and 23-Iliamna River (Figure 6a, 6c); the latter population spawns later in the season than the majority of Iliamna Lake tributary populations. No significant divergence was evident between mainland-beach sites 20-Finger Beach and 24-Knutson Beach (all tests of differentiation: p > 0.1; see additional file 1), and both appeared significantly differentiated from tributaries for 'Outlier 2' with exception of 16-Chinkelyes Creek (Figure 6c), but less for the other two sets (Figure 6a, 6b).

Principal coordinate analysis (PCO) between sockeye salmon populations from Iliamna Lake. Based on (a) 38 SNPs ('No Outliers'), (b) 39 SNPs including One_MHC2-190 ('Outlier 1'), or (c) 39 SNPs including One_MHC2-251 ('Outlier 2'). Population numbers can be found in Table 1. Population legends--tributary spawners: empty squares; island-beach spawners: black circles; mainland-beach spawners: grey triangles; Iliamna River (#23, a late-spawning population, Table 1): black square.

We found a significant isolation-by-distance relationship between Iliamna Lake populations even if we ignored habitat differences between them, although determination coefficients were low for all three sets ('No Outliers' R2 = 0.06; 'Outlier 1' R2 = 0.07; 'Outlier 2' R2 = 0.15). These values underwent a two- to five-fold increase once we conducted separate isolation-by-distance analyses for different spawning habitats (Figure 7a-c). Dispersal was thus more likely to occur between tributary populations only than between tributary and island-beach populations, or between tributary and mainland-beach spawners, though only for the 'Outlier 2' set (Figure 7c).

Scatterplots of genetic ( F ST ) vs. geographic distances between sockeye salmon populations from Iliamna Lake. Scatterplots used (a) 38 SNPs ('No Outliers'), (b) 39 SNPs including One_MHC2-190 ('Outlier 1'), or (c) 39 SNPs including One_MHC2-251 ('Outlier 2'). Legend for population comparisons--tributary-tributary: yellow squares; tributary-island beach: purple circles; tributary-mainland beach: red circles. Regression lines and coefficients of determination (R2) were only reported for tributary-island beach (purple) and tributary-tributary comparisons (black) as no significant isolation-by-distance patterns were found for tributary-mainland beach comparisons.

Discussion

Hierarchical divergence between Alaskan sockeye salmon populations: the roles of geography and ecology at varying spatial scales

Our premise, that geography and ecology should hierarchically influence population divergence between Kvichak River sockeye salmon populations, was largely supported by various spatial analyses using SNPs. Simple and partial Mantel tests suggested a greater role of geographic distance than differences in spawn timing for the entire drainage. The positive relationship between large-scale genetic and geographic distances was likely driven by discrete genetic differences between lakes as hierarchical AMOVA and the neighbour-joining tree implied: the largest differentiation occurred between populations from distinct lakes followed by differences between populations within lakes. Differences between the two subdrainages in the region (Alagnak and Kvichak) were prominent as well, especially after accounting for the differentiation of Lake Clark.

Large-scale divergence between sockeye salmon populations in the Kvichak River may have initially evolved from historical contingency, followed by contemporary adaptation. Recolonization of lakes and subdrainages was likely sequential as ice sheets retreated after the Late Wisconsin glacial maximum [42]. The best example to illustrate this point is Lake Clark: glacier retreat has only occurred during the last few hundred years in some areas, such as the 13-Upper Tlikakila River [46]. Lake Clark sockeye salmon populations may have therefore become established only very recently. Areas of difficult migratory passage on the Newhalen River below Lake Clark and Sixmile Lake may have also caused bottlenecks during or after the colonization events. Consistent with these findings, Lake Clark populations harboured the lowest estimates of SNP genetic diversity in our study; moreover, an earlier survey using microsatellite DNA indicated widespread presence of bottlenecked populations throughout Lake Clark [46]. Differences in HE and AR were also noticeable between the Alagnak and Kvichak subdrainages, which can be attributed to differences in both number and size of populations. For instance, sockeye salmon have historically been much more abundant in the Kvichak than the Alagnak systems [57, 58], though recently there has been a surge in abundance among Alagnak populations [59].

Contemporary adaptation to distinct limnetic environments may also help explain the high fidelity of returning adults. Reproductive isolation between nursery lakes is typical of lake-type sockeye salmon, which spend half of their lives rearing in freshwater before migrating to sea [13, 44, 60–62]. Lake-type sockeye salmon are characterized by a low tendency to disperse, limiting gene flow and enhancing reproductive isolation between populations [14]. Olfactory imprinting during juvenile stages allows lake-type adult salmon to recognize their natal sites [18, 19]. In addition to homing, timing of spawning further isolate populations occupying different lakes [49], although its importance may be secondary as suggested by Mantel tests. For instance, Lake Clark populations tend to spawn during early fall, in contrast to populations from Sixmile and Iliamna lakes that spawn from middle to late summer, thus supporting the idea that temporal segregation reduces gene flow [46, 47, 49, 63, 64].

The role of ecology (spawn timing and habitat) was more prominent at fine scales or for intralake patterns of divergence, with geographic distance having a significant but secondary role. This conclusion was drawn from analyses conducted within Iliamna Lake, a large and population-rich lake harbouring three different spawning habitats. Mantel tests for one SNP set ('Outlier 2') strongly suggested that variable timing of spawning, particularly among populations of the three spawning-habitat types (see summary in additional file 3), may be the most important barrier to dispersal between these populations. Salmon populations are generally composed of early, late, and even intermediate migrants that breed asynchronously [24, 47]. Variable timing of reproduction between spawning-habitat types is thought to be function of historical thermal regimes at the incubation sites of the progeny [23, 24]. Temperatures and various other physical attributes vary substantially among tributary, mainland-beach, and island-beach habitats (additional file 3: see also [65–67], which together have promoted locally adapted populations. PCO and isolation-by-distance plots reiterated our expectation that dispersal was more likely to occur between sockeye salmon populations spawning within the same habitat as seen in the Wood River, Alaska [48]. This was particularly striking for the homogeneous group of island beaches as they consistently clustered far from tributaries and mainland beaches. Historical abundances among island-beach populations spanning 45 years of aerial surveys appeared highly correlated [67], which mirrors the genetic homogeneity found in this and other studies [68]. Unique habitat characteristics of island beaches have likely driven this marked divergence (additional file 3). Island-beach populations spawn during an unusually contracted period (about 2 weeks), from early to middle August, in mild wind-circulated water. Temperatures in the range 10 - 13°C allow embryos to hatch prior to freezing in early December; conversely, embryos hatch much later among mainland beaches and tributaries [45]. Island-beach sockeye salmon are also younger and smaller for a given age than tributary sockeye salmon, suggestive of distinct norms of reaction between growth and maturation [45]. Island and mainland beaches further differ in gravel size of incubation sites, which selects for larger eggs among females in island- than mainland-beach spawners [69].

Differences between mainland beaches and tributaries were more obvious for 'Outlier 2' (39 SNPs, including the intronic One_MHC2-251) than for the other two sets: 'No Outliers' (38 SNPs, excluding One_MHC2-190 and One_MHC2-251) suggested mild separation, whereas 'Outlier 1' (39 SNPs, including the exonic One_MHC2-190) indicated no clear separation. Assuming MHC introns have shorter coalescent times than exons (see following section, Nonsynonymous and linked SNPs in the MHC class II), populations from mainland beaches may have diversified only recently from tributaries, and different SNP sets reflect different times since divergence. Consistent with this hypothesis, mainland beach populations appeared undifferentiated from 16-Chinkelyes Creek, a tributary of the Iliamna River, implying that habitat-driven isolation is incomplete. It is possible that populations from 16-Chinkelyes Creek and adjacent tributaries colonized 20-Finger Beach given that only ca. 5 km separates it from the mouth of Iliamna River, where 16-Chinkelyes Creek drains. Interestingly, 23-Iliamna River also clustered more closely to mainland beaches than the majority of tributary spawners. We speculate that the four populations from the east of Iliamna Lake (16-Chinkelyes Creek, 20-Finger Beach, 24-Knutson Beach, and 23-Iliamna River) shared a common ancestor. Likely, divergent attributes of their breeding sites as well as discrete patterns of spawn timing have driven them apart over time.

Overall, the fact that geography and ecology have influenced genetic divergence and structure of Kvichak River sockeye salmon in a hierarchical manner has fundamental and applied implications. First, it provides a compelling mechanism for reproductive isolation at varying scales, including isolation-by-distance [50] and isolation-by-time [47]. Also, and because there is substantial phenotypic divergence between spawning ecotypes (additional file 3), it is possible that gene flow is maladaptive between these populations (i.e., immigrants have lower reproductive success than residents). This hypothesis is consistent with findings from another lake system that drains into Bristol Bay, where dispersers between beach and tributary habitats resemble phenotypically their recipient rather than their source populations [21]. Second, it reinforces the importance of maintaining the integrity of all hierarchical levels of intraspecific biodiversity or biocomplexity [9], which have evolved during thousands of years [15], but are currently threatened by anthropogenic changes that have intensified during the last century [12].

Nonsynonymous and linked SNPs in the MHC class II: evidence for adaptive divergence at the molecular level?

Two SNPs found in one exon (One_MHC2-190) and one intron (One_MHC2-251) within the MHC class II locus appeared robust to violations of demographic assumptions (e.g., bottlenecks, hierarchical structure) and consistently appeared as outliers during genome scans. MHC class II genes are translated on the surface of antigen-presenting B cells and macrophages and play a key role in the successful mounting of the immune response of vertebrates [70]. Several investigations support the adaptive nature of MHC polymorphisms resulting from pathogen-mediated selection [53, 71–74]. Adaptive variation in the MHC is thus likely to affect mate choice, because parents would try to increase pathogen resistance in the offspring, avoid inbreeding, or both [70]. Miller et al. [53] concluded that balancing selection is a strong candidate to maintain the allele diversity of the MHC class II locus in Fraser River sockeye salmon (Canada), including the substitution found at One_MHC2-190 located in the antigen recognition site. Yet, evidence for diversifying selection or neutrality of alleles could not be ruled out for some populations [53].

We hypothesize that large FST estimates for MHC SNPs (One_MHC2-190 FST = 0.434; One_MHC2-251 FST = 0.387) in comparison with putatively neutral loci are consistent with signatures of diversifying selection; such force is expected to drive adaptive mutations and tightly linked sites to fixation by positive selection, hence increasing differentiation between populations [33]. Kvichak River sockeye salmon populations may have evolved resistance or immunocompetence to specific pathogens that vary in space [53]. Three other studies in salmonids have found signatures of diversifying selection at MHC class I and II gene-linked markers that were also characterized by elevated estimates of population differentiation [75–77].

Even though the argument for diversifying selection seems compelling, it is based on a genome scan involving only 42 nuclear loci, a limitation of most genetic surveys in nonmodel organisms [31, 32]. Evaluating alternative hypotheses for the evolution of MHC genes among Kvichak River sockeye salmon populations may be appropriate in the light of some additional findings. In particular, we found that nuclear SNP sets with and without outliers were significantly correlated for the entire drainage. Landry & Bernatchez [78] compared MHC class II and microsatellite alleles for Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) from Central Québec (Canada), and concluded that between-river differentiation was highly correlated between alleles of different marker types, whereas within-river differentiation was not. For Kvichak River sockeye salmon, it is feasible that neutral evolution has played a more prominent role than selection influencing large-scale divergence. Moreover, recent studies argue that the evolution of MHC variation may proceed in neutral fashion: estimates of population divergence from MHC genes appear no different from estimates using neutrally evolving microsatellite DNA markers [79–81].

Could differences between SNP sets found at fine spatial scales be also attributed to selection at the molecular level? Within Iliamna Lake only, differences were evident among 'No Outliers', 'Outlier 1', and 'Outlier 2' sets, including results from PCO and Mantel tests relating spawn timing and genetic distances. These differences were expected if diversifying selection affects those sets containing MHC outliers ('Outlier 1', 'Outlier 2', or both) but not the putatively neutral set ('No Outliers'). The observed dichotomy between sets containing the MHC exon ('Outlier 1') and MHC intron ('Outlier 2') was however unexpected based on the premise that diversifying selection should fix variation in tightly linked sites around the adaptive mutation; here, we have assumed that the MHC exon may have a selective advantage, whereas the MHC intron is subjected to hitchhiking selection [33]. We propose that differences between 'Outlier 1' and 'Outlier 2' may reflect varying coalescent times and thus provide distinct measures of time since population divergence. Introns coalesce more rapidly than exons, because variation in the latter can be maintained by balancing selection, a mechanism that has been demonstrated in MHC exon-intron boundaries where recombination occurs [82, 83].

In summary, diversifying selection--as suggested by outlier analyses--acting on two SNPs found in the MHC class II locus complex remains one possible hypothesis with support from other three studies in salmonids. However, neutral evolution of these polymorphisms and impacts of balancing selection represent alternatives that may operate at varying spatial scales. Resolving between these hypotheses is beyond the scope of this investigation; we encourage further studies in sockeye salmon that address mate choice [81] as well as pathogen-host interactions [72–74] to discern between these alternatives.

Conclusions

Two main conclusions emerge from this study. First, we have demonstrated that geography and ecology have hierarchically influenced genetic divergence between Kvichak River sockeye salmon populations depending on the spatial scale. Contrasts between lakes, subdrainages, and geographic distance dominated large-scale differentiation, whereas differences in the timing of spawning linked to discrete spawning habitat dominated fine-scale (intralake) differentiation. Second, we determined signatures of selection in two SNPs located in the MHC class II that appeared robust to violations of demographic assumptions. We propose that one possible mechanism that has driven the evolution of these SNPs is diversifying selection in response to local pathogens; however, neutral evolution of these polymorphisms at large spatial scales, as well as effects of balancing selection at fine spatial scales, cannot be ruled out at this stage. Both conclusions imply that historical contingency and contemporary adaptation have driven differentiation between Kvichak River sockeye salmon populations, as revealed by a suite of SNPs. Our findings highlight the need for conservation of complex population structure, because it provides resilience in the face of environmental change, both natural and anthropogenic.

Methods

Samples and population attributes

Adult sockeye salmon (n = 3,945) were taken from a larger collection of reference populations used for identification of juvenile mixtures in the high seas of the northern Pacific Ocean [41]. Briefly, spawning grounds associated with six major lakes--Battle, Kukaklek, Nonvianuk, Iliamna, Sixmile, and Clark--were surveyed between 1999 and 2006 (Figure 1 and Table 1). Temporal replicates taken in the same location one or more years apart were pooled following earlier assessment guidelines [84], but samples from discrete early- or late-migrant collections were kept separate. Populations were classified according to the type of spawning habitat: mainland beaches, island beaches, or tributaries (Table 1). In both beach types the salmon spawn in the lake itself, but the mainland- and island-beach habitats differ markedly in a number of physical attributes including temperature, gravel size, and flow regime. Consequently, the salmon using these beaches differ in life-history traits such as size at age, age composition, egg size, and spawn timing [45, 69]. Habitat characteristics of the three spawning ecotypes and their life-history attributes can be found in additional file 3. We estimated historical dates (day and month) of peak spawning activity (spawn timing, hereafter) as the median of the spawning period reported by Regnart [85] for the Kvichak subdrainage, or the approximate date with the highest live-to-dead fish ratio reported by Clark [57] for the Alagnak subdrainage. Peak spawning dates reported by Ramstad et al. [46] were also used as reference for some populations. When spawning periods were unavailable for some populations of the Kvichak subrainage, we calculated the median of the spawning period for the geographic group they belong to. For some late- or early-migrant populations (Table 1) we used the collection date as spawning date.

Genotyping

Uniplex and array-based genotyping followed Seeb et al. [86]. All individuals were genotyped for a panel of 45 SNPs spanning 42 nuclear and three mitochondrial loci [39–41]. Quality control consisted of re-genotyping of 8% of each population to ensure accuracy and reproducibility. Genotyping error was estimated in less than 0.5% [41].

Detection of outliers (genome scans)

We employed BAYESCAN to identify outliers or those SNPs characterized by higher or lower levels of population divergence than strictly neutral loci, suggestive of diversifying or balancing selection, respectively [51]. BAYESCAN incorporates locus- as well as population-specific regression terms, therefore avoiding unrealistic assumptions of previous methods, such as an island model of migration, symmetrical gene flow, and equal population sizes [31, 51]. Prior to simulations, we removed mitochondrial SNPs and monomorphic nuclear SNPs (using a cutoff criterion of >0.98 for the most common allele). Inclusion of monomorphic markers resulted in 40% of our SNPs being outliers, which we considered an unrealistic outcome (authors' unpublished results; see also [31]). After 10 pilot runs of 5000 iterations each, default values of proposed distributions were updated throughout 100,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo steps after an initial burn-in of 50,000 steps. We assumed chains converged if acceptance rates ranged between 0.25 and 0.45. The top criterion of 'decisive' (log10 Bayes Factor: 2 - 5), which corresponds roughly to a posterior probability range of 0.99 - 1, was indicative that a locus was affected by selection. BAYESCAN simulations were repeated after iteratively removing groups of populations (lakes or subdrainages) to investigate if outliers had a specific geographic origin. This was done in conjunction with allele frequency plots across multiple populations to ascertain geographic trends.

We also used Arlequin 3.5 [52] to detect outlier loci taking into account the hierarchical structure of the Kvichak River, wherein dispersal is likely to be more predominant within subdrainages than between subdrainages. Even though BAYESCAN incorporates population-specific terms, it is unclear whether it takes into account hierarchical structure in its decision-making process. We ran 20,000 simulations assuming 100 demes per group, two hierarchical groups (subdrainages), and a hierarchical island model. These analyses were performed following the exclusion of strongly differentiated populations (Lake Clark) that were flagged in the previous analysis using BAYESCAN.

Outlier loci were classified as exonic or intronic using BLASTX or TBLASTX (National Center for Biotechnology Information) to gauge the scope of selection acting directly on these markers. We followed Smith et al. [39] guidelines that considered an alignment significant if an E-value < 10-5 was found.

Linkage disequilibrium and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium tests

We tested for deviations from linkage equilibrium between markers in each population using GENEPOP 4.0 [87]. Exact probabilities using a Markov Chain consisting of 100 batches and 5000 iterations per batch were calculated. Correction for multiple tests was done using a sequential Bonferroni correction for multiple k tests [88]. For SNPs in significant linkage disequilibrium, we removed the least informative of the pair based on Shannon-Weaver's index (I) per locus supplied by GENALEX 6.3 [89]. Linked mitochondrial SNPs were combined into haplotypes following Habicht et al. [41] and analyzed separately from nuclear SNPs.

Deviations from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium among nuclear SNPs were estimated in GENALEX with probabilities for locus-specific χ2 tests. Multilocus HWE goodness-of-fit probabilities were calculated by summing across loci (degrees of freedom = number of loci).

Genetic diversity and differentiation

Estimation of allele frequencies and heterozygosities (observed and expected) for nuclear SNPs was done in GENALEX. Allelic richness or the number of alleles corrected for sample size was additionally estimated using a rarefaction method implemented in FSTAT 2.9.3 [90, 91]. Correlation between allelic richness and expected heterozygosity was judged employing Spearman R coefficient in SPSS 17.0. For mitochondrial SNPs, we calculated haplotype frequencies in GENALEX via the AMOVA option for haploid data. Differences in genetic diversity between spatial groups (e.g., subdrainages, lakes) were evaluated using nonparametric Kruskall-Wallis χ2 tests or Mann-Whitney U-tests for multiple and pairwise comparisons, respectively, using SPSS 17.0.

For nuclear SNPs, global FST plus confidence intervals (95% CI) were obtained from FSTAT, whereas pairwise FST values were calculated in GENALEX along with population differentiation tests based on 1000 permutations. Global differentiation tests for FST were calculated in GENEPOP using Fisher's method. For mitochondrial SNP haplotypes we quantified global differentiation using ΦPT [92] in GENALEX.

Hierarchical analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA)

We employed the AMOVA option in GENALEX to partition the total genetic variance within and between regions. Hierarchical regions corresponded to either subdrainages or lakes. AMOVA first included populations from the entire drainage; variance components were recalculated after excluding highly differentiated populations to account for an uneven distribution of the total genetic variance. Our objective was to define which grouping explained the highest proportion of the variance. Permutations (1000 times) of elements between and within regions were carried out using Φ-statistics [92] to enable comparisons between nuclear and mitochondrial SNPs.

Spatial genetic structure

Using PHYLIP [93] we built an unrooted neighbour-joining tree from a matrix of Cavalli-Sforza & Edwards [55] chord distances between populations for the entire drainage. Branch bootstrap support--the percentage each branch appeared in a consensus tree built from 1000 resampled ones--was also estimated; bootstrap support values higher than 50% were reported to highlight those branches that consistently appeared in the bootstrap consensus tree. Branch lengths and tree topologies were visualized in Treeview [94]. Additionally, we used TreeFit [56] to calculate a R2-value that explains how well the branch lengths of a bifurcating tree captures the variation of the distance matrix. Kalinowski [56] suggests that only trees with R2 >0.90 reliably reflect the underlying spatial genetic structure of a distance matrix.

We used a principal coordinate analysis (PCO) in GENALEX to summarize multidimensional genetic data between populations within Iliamna Lake. Pairwise FST were preferred at fine scales instead of Cavalli-Sforza & Edwards [51] chord distances. Scores from the first two eigenvectors were plotted, which often accounted for 50% or more of the total variation in the data.

Testing the relative influence of geographic distance and ecological factors (spawn timing and habitat) on population divergence

Geographic distances (km) corresponded to direct waterway distances calculated in the DeLorme Topo USA® 6.0 software (Alagnak subdrainage) or were taken from a spatial analysis of historical abundances among populations of the Kvichak subdrainage [67]. The difference in spawn timing (days) corresponded to the absolute difference between peak spawning dates of two populations. Associations between these variables and genetic distances were tested in the software ZT [95] using simple and partial Mantel tests. Whereas simple Mantel tests can be used to estimate the strength of the correlation between two matrices of distances, partial Mantel tests enable inclusion of a third matrix that is held constant [96]. A partial test may be more informative than a simple Mantel test to gauge the relative importance of the two factors that simultaneously influence genetic structure. Mantel tests were performed for the entire drainage (large scale) and for Iliamna Lake populations only (fine scale), which concentrated the highest number of populations and the greatest diversity of spawning-habitat types. We reported Pearson correlation coefficients (r) and their p-values after 10000 randomizations. Independence of geographic distances and differences in spawn timing was verified at large scales (entire drainage: r = -0.015, p = 0.464) and fine scales (Iliamna Lake: r = 0.14, p = 0.13).

Because spawning-habitat type was a categorical variable, it was not included in Mantel tests. However, we explored whether dispersal gauged through isolation-by-distance patterns [50] was more likely to occur between populations spawning in the same habitat than different habitats (tributary, island beach, and mainland beach) in Iliamna Lake. Because tributary populations outnumbered the other two, we recalculated correlation values between pairwise FST and geographic distance for tributary-to-tributary, tributary-to-island-beach, and tributary-to-mainland-beach population comparisons. Linearized (FST/1 - FST: Rousset et al. [97]) or standard pairwise FST generated identical results; we thus opted for the latter measure for simplicity.

Ethics statement

Experimental research reported in this manuscript consisted of genetic analyses of animal tissues collected from wild populations. Collection was done in compliance with protocols from the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and permits from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

References

Nosil P: Ernst Mayr and the integration of geographic and ecological factors in speciation. Biol J Linn Soc. 2008, 95: 26-46. 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.01091.x.

Waples RS, Teel DJ, Myers JM, Marshall AR: Life-history divergence in Chinook salmon: Historic contingency and parallel evolution. Evolution. 2004, 58: 386-403.

Dionne M, Caron F, Dodson JJ, Bernatchez L: Landscape genetics and hierarchical genetic structure in Atlantic salmon: the interaction of gene flow and local adaptation. Mol Ecol. 2008, 17: 2382-2396. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03771.x.

Mila B, Wayne RK, Fitze P, Smith TB: Divergence with gene flow and fine-scale phylogeographical structure in the wedge-billed woodcreeper, Glyphorynchus spirurus, a Neotropical rainforest bird. Mol Ecol. 2009, 18: 2979-2995. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04251.x.

Mila B, Warren B, Heeb P, Thebaud C: The geographic scale of diversification on islands: genetic and morphological divergence at a very small spatial scale in the Mascarene grey white-eye (Aves: Zosterops borbonicus). BMC Evol Biol. 2010, 10: 158-10.1186/1471-2148-10-158.

Matocq MD, Patton JL, da Silva MNF: Population genetic structure of two ecologically distinct Amazonian spiny rats: Separating history and current ecology. Evolution. 2000, 54: 1423-1432.

Drummond CS, Hamilton MB: Hierarchical components of genetic variation at a species boundary: population structure in two sympatric varieties of Lupinus microcarpus (Leguminosae). Mol Ecol. 2007, 16: 753-769. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03186.x.

Fraser DJ, Bernatchez L: Adaptive evolutionary conservation: towards a unified concept for defining conservation units. Mol Ecol. 2001, 10: 2741-2752.

Hilborn R, Quinn TP, Schindler DE, Rogers DE: Biocomplexity and fisheries sustainability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003, 100: 6564-6568. 10.1073/pnas.1037274100.

Ruzzante D, Mariani S, Bekkevold D, Andre C, Mosegaard H, Clausen L, Dahlgren T, Hutchinson W, Hatfield E, Torstensen E, et al: Biocomplexity in a highly migratory pelagic marine fish, Atlantic herring. Proc R Soc B. 2006, 273: 1459-1464. 10.1098/rspb.2005.3463.

Olsen EM, Knutsen H, Gjosaeter J, Jorde PE, Knutsen JA, Stenseth NC: Small-scale biocomplexity in coastal Atlantic cod supporting a Darwinian perspective on fisheries management. Evol Appl. 2008, 1: 524-533. 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2008.00024.x.

Schindler DE, Hilborn R, Chasco B, Boatright CP, Quinn TP, Rogers LA, Webster MS: Population diversity and the portfolio effect in an exploited species. Nature. 2010, 465 (7298): 609-612. 10.1038/nature09060.

Wood CC: Life history variation and population structure in sockeye salmon. Am Fish Soc Symp. 1995, 17: 195-216.

Wood CC, Bickham JW, Nelson RJ, Foote CJ, Patton JC: Recurrent evolution of life history ecotypes in sockeye salmon: implications for conservation and future evolution. Evol Appl. 2008, 1: 207-221. 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2008.00028.x.

Waples RS, Pess GR, Beechie T: Evolutionary history of Pacific salmon in dynamic environments. Evol Appl. 2008, 1: 189-206. 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2008.00023.x.

Hendry AP, Castric V, Kinnison MT, Quinn TP: The Evolution of Philopatry and Dispersal: Homing vs. Straying in Salmonids. Evolution Illuminated: Salmon and Their Relatives. Edited by: Hendry AP, Stearns SC. 2004, New York: Oxford University Press, 52-91.

Ramstad KM, Woody CA, Allendorf FW: Recent local adaptation of sockeye salmon to glacial spawning habitats. Evol Ecol. 2010, 24: 391-411. 10.1007/s10682-009-9313-5.

Dittman AH, Quinn TP: Homing in Pacific salmon: Mechanisms and ecological basis. J Exp Biol. 1996, 199: 83-91.

Quinn TP: The Behavior and Ecology of Pacific Salmon and Trout. 2005, Seattle: University of Washington Press

Quinn TP, Wetzel L, Bishop S, Overberg K, Rogers DE: Influence of breeding habitat on bear predation and age at maturity and sexual dimorphism of sockeye salmon populations. Can J Zool. 2001, 79: 1782-1793. 10.1139/cjz-79-10-1782.

Lin J, Quinn TP, Hilborn R, Hauser L: Fine-scale differentiation between sockeye salmon ecotypes and the effect of phenotype on straying. Heredity. 2008, 101: 341-350. 10.1038/hdy.2008.59.

Brannon EL: Mechanisms stabilizing salmonid fry emergence timing. Can Spec Pub Fish Aquat Sci. 1987, 96: 120-124.

Hodgson S, Quinn TP: The timing of adult sockeye salmon migration into fresh water: adaptations by populations to prevailing thermal regimes. Can J Zool. 2002, 80: 542-555. 10.1139/z02-030.

Boatright C, Quinn T, Hilborn R: Timing of adult migration and stock structure for sockeye salmon in Bear Lake, Alaska. Trans Am Fish Soc. 2004, 133: 911-921. 10.1577/T03-142.1.

Brumfield RT, Beerli P, Nickerson DA, Edwards SV: The utility of single nucleotide polymorphisms in inferences of population history. Trends Ecol Evol. 2003, 18: 249-256. 10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00018-1.

Morin PA, Luikart G, Wayne RK, Grp SNPW: SNPs in ecology, evolution and conservation. Trends Ecol Evol. 2004, 19: 208-216. 10.1016/j.tree.2004.01.009.

Seeb JE, Pascal CE, Grau ED, Seeb LW, Templin WD, Harkins T, Roberts SB: Transcriptome sequencing and high-resolution melt analysis advance single nucleotide polymorphism discovery in duplicated salmonids. Mol Ecol Res. 2011, 11: 335-348. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02936.x.

Seeb JE, Carvalho GR, Hauser L, Naish KA, Roberts SB, Seeb LW: Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) discovery and applications of SNP genotyping in nonmodel organisms. Mol Ecol Res. 2011, 11: 1-8. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02979.x.

Smith CT, Antonovich A, Templin WD, Elfstrom CM, Narum SR, Seeb LW: Impacts of marker class bias relative to locus-specific variability on population inferences in Chinook salmon: A comparison of single-nucleotide polymorphisms with short tandem repeats and allozymes. Trans Am Fish Soc. 2007, 136: 1674-1687. 10.1577/T06-227.1.

Smith CT, Seeb LW: Number of alleles as a predictor of the relative assignment accuracy of short tandem repeat (STR) and single-nucleotide-polymorphism (SNP) baselines for chum salmon. Trans Am Fish Soc. 2008, 137: 751-762. 10.1577/T07-104.1.

Nielsen EE, Hansen J, Poulsen N, Loeschcke V, Moen T, Johansen T, Mittelholzer C, Taranger G, Ogden R, Carvalho GR: Genomic signatures of local directional selection in a high gene flow marine organism; the Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua). BMC Evol Biol. 2009, 9: 276-10.1186/1471-2148-9-276.

Luikart G, England PR, Tallmon D, Jordan S, Taberlet P: The power and promise of population genomics: From genotyping to genome typing. Nat Rev Genet. 2003, 4: 981-994. 10.1038/nrg1226.

Storz JF: Using genome scans of DNA polymorphism to infer adaptive population divergence. Mol Ecol. 2005, 14: 671-688. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02437.x.

Wilding CS, Butlin RK, Grahame J: Differential gene exchange between parapatric morphs of Littorina saxatilis detected using AFLP markers. J Evol Biol. 2001, 14: 611-619. 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00304.x.

Vasemagi A, Nilsson J, Primmer CR: Expressed sequence tag-linked microsatellites as a source of gene-associated polymorphisms for detecting signatures of divergent selection in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Mol Biol Evol. 2005, 22: 1067-1076. 10.1093/molbev/msi093.

Nosil P, Funk DJ, Ortiz-Barrientos D: Divergent selection and heterogeneous genomic divergence. Mol Ecol. 2009, 18: 375-402. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03946.x.

Hofer T, Ray N, Wegmann D, Excoffier L: Large allele frequency differences between human continental groups are more likely to have occurred by drift during range expansions than by selection. Ann Hum Genet. 2009, 73: 95-108. 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2008.00489.x.

Excoffier L, Hofer T, Foll M: Detecting loci under selection in a hierarchically structured population. Heredity. 2009, 103 (4): 285-298. 10.1038/hdy.2009.74.

Smith CT, Elfstrom CM, Seeb LW, Seeb JE: Use of sequence data from rainbow trout and Atlantic salmon for SNP detection in Pacific salmon. Mol Ecol. 2005, 14: 4193-4203. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02731.x.

Elfstrom CM, Smith CT, Seeb JE: Thirty-two single nucleotide polymorphism markers for high-throughput genotyping of sockeye salmon. Mol Ecol Notes. 2006, 6: 1255-1259. 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2006.01507.x.

Habicht C, Seeb LW, Myers KW, Farley EV, Seeb JE: Summer-Fall Distribution of Stocks of Immature Sockeye Salmon in the Bering Sea as Revealed by Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms. Trans Am Fish Soc. 2010, 139: 1171-1191. 10.1577/T09-149.1.

Stilwell KB, Kaufman DS: Late Wisconsin glacial history of the northern Alaska peninsula, southwestern Alaska, USA. Arctic Alpine Res. 1996, 28: 475-487. 10.2307/1551858.

Habicht C, Olsen JB, Fair L, Seeb JE: Smaller effective population sizes evidenced by loss of microsatellite alleles in tributary-spawning populations of sockeye salmon from the Kvichak River, Alaska drainage. Environ Biol Fish. 2004, 69: 51-62. 10.1023/B:EBFI.0000022887.62009.54.

Habicht C, Seeb LW, Seeb JE: Genetic and ecological divergence defines population structure of sockeye salmon populations returning to Bristol Bay, Alaska, and provides a tool for admixture analysis. Trans Am Fish Soc. 2007, 136: 82-94. 10.1577/T06-001.1.

Blair GR, Rogers DE, Quinn TP: Variation in life history characteristics and morphology of sockeye salmon in the Kvichak River system, Bristol Bay, Alaska. Trans Am Fish Soc. 1993, 122: 550-559. 10.1577/1548-8659(1993)122<0550:VILHCA>2.3.CO;2.

Ramstad KM, Woody CA, Sage GK, Allendorf FW: Founding events influence genetic population structure of sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) in Lake Clark, Alaska. Mol Ecol. 2004, 13: 277-290. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.2062.x.

Hendry AP, Day T: Population structure attributable to reproductive time: isolation by time and adaptation by time. Mol Ecol. 2005, 14: 901-916. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02480.x.

McGlauflin MT, Schindler DE, Seeb LW, Smith CT, Habicht C, Seeb JE: Spawning habitat and geography influence population structure and juvenile migration timing of sockeye salmon in the Wood River lakes, Alaska. Trans Am Fish Soc.

Creelman E, Hauser L, Simmons R, Templin WD, Seeb LW: Temporal and geographic genetic divergence: Characterizing sockeye salmon populations in the Chignik watershed, Alaska, using single nucleotide polymorphisms. Trans Am Fish Soc.

Slatkin M: Isolation by distance in equilibrium and nonequilibrium populations. Evolution. 1993, 47: 264-279. 10.2307/2410134.

Foll M, Gaggiotti O: A Genome-Scan Method to Identify Selected Loci Appropriate for Both Dominant and Codominant Markers: A Bayesian Perspective. Genetics. 2008, 180: 977-993. 10.1534/genetics.108.092221.

Excoffier L, Lischer HEL: Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Res. 2010, 10: 564-567. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x.

Miller KM, Kaukinen KH, Beacham TD, Withler RE: Geographic heterogeneity in natural selection on an MHC locus in sockeye salmon. Genetica. 2001, 111: 237-257. 10.1023/A:1013716020351.

Miller KM, Withler RE: Sequence analysis of a polymorphic MHC class II gene in Pacific salmon. Immunogenetics. 1996, 43: 337-351. 10.1007/BF02199802.

Cavalli-Sforza LL, Edwards AWF: Phylogenetic analysis: models and estimation procedures. Evolution. 1967, 21: 550-570. 10.2307/2406616.

Kalinowski ST: How well do evolutionary trees describe genetic relationships among populations?. Heredity. 2009, 102: 506-513. 10.1038/hdy.2008.136.

Clark JH: Abundance of sockeye salmon in the Alagnak River system of Bristol Bay Alaska. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Fishery Manuscript No. 05-01. 2005, Anchorage

Fair LF: Critical elements of Kvichak River sockeye salmon management. Alaska Fish Res Bull. 2003, 10: 95-103.

Schindler DE, Leavitt PR, Johnson SP, Brock CS: A 500-year context for the recent surge in sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) abundance in the Alagnak River, Alaska. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 2006, 63: 1439-1444. 10.1139/F06-069.

Seeb LW, Habicht C, Templin WD, Tarbox KE, Davis RZ, Brannian LK, Seeb JE: Genetic diversity of sockeye salmon of Cook Inlet, Alaska, and its application to management of populations affected by the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Trans Am Fish Soc. 2000, 129: 1223-1249. 10.1577/1548-8659(2000)129<1223:GDOSSO>2.0.CO;2.

Withler RE, Le KD, Nelson RJ, Miller KM, Beacham TD: Intact genetic structure and high levels of genetic diversity in bottlenecked sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) populations of the Fraser River, British Columbia, Canada. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 2000, 57: 1985-1998. 10.1139/cjfas-57-10-1985.

Beacham TD, Varnavskaya NV, McIntosh B, MacConnachie C: Population structure of sockeye salmon from Russia determined with microsatellite DNA variation. Trans Am Fish Soc. 2006, 135: 97-109. 10.1577/T05-118.1.

Varnavskaya NV, Wood CC, Everett RJ, Wilmot RL, Varnavsky VS, Midanaya VV, Quinn TP: Genetic differentiation of subpopulations of sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) within lakes of Alaska, British Columbia, and Kamchatka, Russia. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 1994, 51: 147-157. 10.1139/f94-301.

Quinn TP, Unwin MJ, Kinnison MT: Evolution of temporal isolation in the wild: Genetic divergence in timing of migration and breeding by introduced chinook salmon populations. Evolution. 2000, 54: 1372-1385.

Hendry AP, Leonetti FE, Quinn TP: Spatial and temporal isolation mechanisms - the formation of discrete breeding aggregations of sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka). Can J Zool. 1995, 73: 339-352. 10.1139/z95-038.

Quinn TP, Volk EC, Hendry AP: Natural otolith microstructure patterns reveal precise homing to natal incubation sites by sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka). Can J Zool. 1999, 77: 766-775. 10.1139/cjz-77-5-766.

Stewart IJ, Hilborn RA, Quinn TP: Coherence of observed adult sockeye salmon abundance within and among spawning habitats in the Kvichak River watershed. Alaska Fish Res Bull. 2003, 10: 28-41.

Stewart IJ, Quinn TP, Bentzen P: Evidence for fine-scale natal homing among island beach spawning sockeye salmon, Oncorhynchus nerka. Environ Biol Fish. 2003, 67 (1): 77-85. 10.1023/A:1024436632183.

Quinn TP, Hendry AP, Wetzel LA: The influence of life history trade-offs and the size of incubation gravels on egg size variation in sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka). Oikos. 1995, 74: 425-438. 10.2307/3545987.

Bernatchez L, Landry C: MHC studies in nonmodel vertebrates: what have we learned about natural selection in 15 years?. J Evol Biol. 2003, 16: 363-377. 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00531.x.

van Oosterhout C, Joyce DA, Cummings SM, Blais J, Barson NJ, Ramnarine IW, Mohammed RS, Persad N, Cable J: Balancing selection, random genetic drift, and genetic variation at the major histocompatibility complex in two wild populations of guppies (Poecilia reticulata). Evolution. 2006, 60: 2562-2574. 10.1554/06-286.1.

Dionne M, Miller KM, Dodson JJ, Caron F, Bernatchez L: Clinal variation in MHC diversity with temperature: Evidence for the role of host-pathogen interaction on local adaptation in Atlantic salmon. Evolution. 2007, 61: 2154-2164. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00178.x.

Dionne M, Miller KM, Dodson JJ, Bernatchez L: MHC standing genetic variation and pathogen resistance in wild Atlantic salmon. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2009, 364: 1555-1565. 10.1098/rstb.2009.0011.

Evans ML, Neff BD: Major histocompatibility complex heterozygote advantage and widespread bacterial infections in populations of Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha). Mol Ecol. 2009, 18: 4716-4729. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04374.x.

Hansen MM, Skaala O, Jensen LF, Bekkevold D, Mensberg KLD: Gene flow, effective population size and selection at major histocompatibility complex genes: brown trout in the Hardanger Fjord, Norway. Mol Ecol. 2007, 16: 1413-1425. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03255.x.

Heath DD, Shrimpton JM, Hepburn RI, Jamieson SK, Brode SK, Docker MF: Population structure and divergence using microsatellite and gene locus markers in Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) populations. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 2006, 63: 1370-1383. 10.1139/F06-044.

Ackerman MW, Habicht C, Seeb LW: SNPs under diversifying selection provide increased accuracy and precision in mixed stock analyses of sockeye salmon from Copper River, Alaska. Trans Am Fish Soc.

Landry C, Bernatchez L: Comparative analysis of population structure across environments and geographical scales at major histocompatibility complex and microsatellite loci in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Mol Ecol. 2001, 10: 2525-2539. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2001.01383.x.

Boyce WM, Hedrick PW, Muggli-Cockett NE, Kalinowski S, Penedo MCT, Ramey RR: Genetic variation of major histocompatibility complex and microsatellite loci: A comparison in bighorn sheep. Genetics. 1997, 145: 421-433.

Miller HC, Allendorf F, Daugherty CH: Genetic diversity and differentiation at MHC genes in island populations of tuatara (Sphenodon spp.). Mol Ecol. 2010, 19: 3894-3908. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04771.x.

Huchard E, Knapp LA, Wang JL, Raymond M, Cowlishaw G: MHC, mate choice and heterozygote advantage in a wild social primate. Mol Ecol. 2010, 19: 2545-2561.

Hughes AL: Evolution of introns and exons of class II major histocompatibility complex genes of vertebrates. Immunogenetics. 2000, 51 (6): 473-486. 10.1007/s002510050646.

Reusch TBH, Langefors A: Inter- and intralocus recombination drive MHC class IIB gene diversification in a teleost, the three-spined stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus. J Mol Evol. 2005, 61: 531-545. 10.1007/s00239-004-0340-0.

Waples RS: Temporal changes of allele frequency in Pacific salmon - implications for mixed-stock fishery analysis. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 1990, 47: 968-976. 10.1139/f90-111.

Regnart JR: Kvichak River sockeye salmon spawning ground surveys, 1955-1996. Regional Information Report 2A96-42. 1996, Anchorage: Alaska Department of Fish and Game

Seeb JE, Pascal CE, Ramakrishnan R, Seeb LW: SNP Genotyping by the 5'-Nuclease Reaction: Advances in High-Throughput Genotyping with Nonmodel Organisms. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms, Methods in Molecular Biology. Edited by: Komar AA. 2009

Rousset F: GENEPOP ' 007: a complete re-implementation of the GENEPOP software for Windows and Linux. Mol Ecol Res. 2008, 8: 103-106. 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01931.x.

Rice WR: Analyzing tables of statistical tests. Evolution. 1989, 43: 223-225. 10.2307/2409177.

Peakall R, Smouse PE: GENALEX 6: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol Ecol Notes. 2006, 6: 288-295. 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2005.01155.x.

Goudet J: FSTAT (Version 1.2): A computer program to calculate F-statistics. J Hered. 1995, 86: 485-486.

Goudet J: FSTAT, a program to estimate and test gene diversities and fixation indices. Ver. 2.9.3. [http://www2.unil.ch/popgen/softwares/fstat.htm]

Peakall R, Smouse PE, Huff DR: Evolutionary implications of allozyme and RAPD variation in diploid populations of dioecious buffalograss Buchloe dactyloides. Mol Ecol. 1995, 4: 135-147. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.1995.tb00203.x.

Felsenstein J: PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package), version 3.6. Distributed by the author. Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washingto. [http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html]

Page RDM: TreeView: An application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996, 12: 357-358.

Van de Peer Y, Bonnet E: zt: a software tool for simple and partial Mantel tests. J Stat Soft. 2002, 7: 1-12.

Smouse PE, Long JC, Sokal RR: Multiple regression and correlation extensions of the Mantel test of matrix correspondance. Syst Zool. 1986, 35: 627-632. 10.2307/2413122.

Rousset F: Genetic differentiation and estimation of gene flow from F-statistics under isolation by distance. Genetics. 1997, 145: 1219-1228.

Acknowledgements

Building the baseline for sockeye salmon in Bristol Bay has been ongoing since the mid-1990s and has been financially supported through funding from the State of Alaska, Alaska Disaster Grant, National Park Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service Office of Subsistence Management, North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission, North Pacific Research Board, National Marine Fisheries Service, and Bristol Bay Science and Research Institute. We thank the many people who helped collect samples used in the baseline, including S. Morstad and other staff from Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) King Salmon office; Gregory Buck and Harry B. Rich, Jr. (University of Washington); C. A. Woody (U.S. Geological Survey), D. Young (National Park Service); and K. Ramstad (University of Montana). We thank the dedicated ADF&G laboratory staff who processed the samples and I. Stewart for facilitating a matrix of geographic distances between populations for the Kvichak subdrainage. We also thank M. Ackerman, L. Creelman, J. Lin, M. McGlauflin, K. O'Malley, and two anonymous reviewers for suggestions on earlier versions of the manuscript. C. Pascal helped with the analysis of SNPs within MHC class II genes. S. Kalinowski and T. Seamons stimulated discussions about the methodological approaches used in the study. Funding for the analysis and writing of this manuscript was provided by a grant to the University of Washington from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

DGU conducted the majority of statistical analyses and was the primary responsible for writing the manuscript. JES conceived and designed the study, helped collect many of the samples and interpret the results, and contributed to drafting and editing the manuscript. MJS performed exploratory spatial and genetic analyses and commented on the manuscript. CH participated in the study design, collected and analyzed genetic data, helped interpreting the results, and commented on earlier drafts. TPQ provided ecological expertise on the system, helped collect many of the samples, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. LWS conceived and designed the study, helped interpret the results, and contributed to drafting and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12862_2010_1655_MOESM1_ESM.XLS

Additional file 1: Pairwise FST values and tests of differentiation between Kvichak River sockeye salmon populations(XLS 113 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Gomez-Uchida, D., Seeb, J.E., Smith, M.J. et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms unravel hierarchical divergence and signatures of selection among Alaskan sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) populations. BMC Evol Biol 11, 48 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-11-48

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-11-48