Abstract

Background

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) was shown previously to modify stretch induced differentiation in the lung. The mechanism for CFTR modulation of lung development was examined by in utero gene transfer of either a sense or antisense construct to alter CFTR expression levels.

The BAT-gal transgenic reporter mouse line, expressing β-galactosidase under a canonical Wnt/β-catenin-responsive promoter, was used to assess the relative roles of CFTR, Wnt, and parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) in lung organogenesis. Adenoviruses containing full-length CFTR, a short anti-sense CFTR gene fragment, or a reporter gene as control were used in an intra-amniotic gene therapy procedure to transiently modify CFTR expression in the fetal lung.

Results

A direct correlation between CFTR expression levels and PTHrP levels was found. An inverse correlation between CFTR and Wnt signaling activities was demonstrated.

Conclusion

These data are consistent with CFTR participating in the mechanicosensory process essential to regulate Wnt/β-Catenin signaling required for lung organogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Organogenesis in the lung requires the sequential development of the large airways, bronchioles and alveoli. The lung begins as a simple structure with increasing complexity that is necessary for efficient air exchange at maturity. Recently, several laboratories have demonstrated that this complex process involves the promotion of mechanical stretch [1–4]. Specifically, muscle contractions of the large airways compress amniotic fluid in the fetal lung generating a pressure gradient that is converted to biochemical signals necessary for cell differentiation.

Mechanical force modulation of biochemical processes is a well known phenomenon that is mediated by multimeric proteins [4, 5]. Mechanicosensing and the genes involved, however, are less well known. Sensing molecules such as integrins, ion channels, and kinase-linked receptors have been implicated in changes in gene expression related to stretch [6]. Most of the evidence from these studies implicates vascular responses to stretch in hemodynamic stasis, although little is known about these sensors in fetal organogenesis.

Recently, control of muscle contractions via the Rho kinase-dependent and independent pathways was shown to be important in lung development [3]. In particular, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) was found to influence muscle contractions in lung development via a Rho kinase-independent mechanism involving ATP and calcium [7]. In other work, we and others demonstrated that the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays crucial roles in lung organogenesis [8, 9]. These studies utilized our laboratory's transient in utero gene transfer technique [10] with sense and antisense constructs to modulate gene expression [11–16]. This technique has the advantage in lung development studies by transiently targeting the developing respiratory epithelium for temporal modulation of gene expression without any inflammatory consequences and no premature expression leakage.

In the study reported here the role of CFTR in downstream regulation of lung differentiation effectors was examined. Specifically, the relationship between CFTR function and Wnt/β-catenin signaling in lung development was examined. Previous studies have suggested that Wnt signaling via a stretch-induced mechanism involving parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) is required for normal lung development [17–20]. Therefore, we used our experimental system to determine if altering CFTR expression has downstream effects on Wnt and PTHrP which would provide further evidence of CFTR involvement in mechanicosensing necessary for normal lung development.

Results

CFTR influences Wnt/β-catenin signaling

BAT-gal reporter mice express β-galactosidase under the control of Wnt//β-catenin-responsive elements [24]. To evaluate the role of CFTR in modulating the Wnt signaling cascade, fetuses from time pregnant BAT-gal mice were injected at E15, E16, and E17 via the amniotic fluid using our established techniques [11, 23, 25]. Recombinant adenoviruses with either eGFP (AdCMVeGFP; control), CFTR (Av1CF2; [12, 13, 15]), or antisense CFTR (AdCMVascftr; [22] were used to alter levels of CFTR gene expression in the developing lung. Tissues were harvested at 24 hours post-gene transfer, homogenized (3–4 fetuses/pool), and β-galactosidase enzyme and total protein assays performed and the enzymatic activity was expressed as units/μg protein.

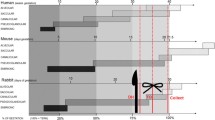

BAT-gal expression during normal lung development was found to be highly regulated. At E16 little if any Wnt/β-catenin-dependent β-galactosidase activity was detected in control tissues (Fig. 1). Enzyme activity peaked at E17 and then decreased by E18. CFTR over expression resulted in a small but significant (p < 0.05) increase in BAT-gal expression at E16. At E17 there was a non-significant decrease in activity in the CFTR-treated animals, and by E18 there was no difference between control and CFTR-treated animals. In contrast, antisense knockdown of CFTR showed highly significant (p < 0.01) increases in BAT-gal activity at E16, E17, and E18 when compared to either control or CFTR-treated animals consistent with a relationship between CFTR expression and canonical Wnt signaling between E16–E18 in the mouse lung.

β-galactosidase activity following in utero modification of CFTR expression. Bat-gal mice were injected at E15, E16, or E17 with adenoviruses expressing eGFP (control), antisense CFTR (ASCFTR), or CFTR and lungs harvested 24 hours later. Tissue was homogenized and β-galactosidase enzyme assays and total protein determinations performed. * p < 0.05.

The distribution by fluorescent immunohistochemistry of β-galactosidase expression was significantly different in fetuses treated at E15 and examined at E16 (Fig. 2A, C, D), AdCMVeGFP, control, lungs showed little or no expression as would be expected from the enzyme assay data presented in Fig. 1. Antisense CFTR treated lungs, which had the largest increase in β-galactosidase enzyme activity, exhibited expression in randomly distributed individual cells (arrows; Fig. 2C). In contrast, CFTR over expression, which showed a smaller but significant increase in enzyme activity, exhibited increased clusters of β-galactosidase expressing cells (arrows; Fig. 2E). In fetuses treated at E16 and examined at E17, normal, control, and CFTR over expression (Fig. 2B and 2F), β-galactosidase was seen around small airways with some expression in the parenchyma consistent with CFTR accelerating the normal developmental Wnt/β-catenin signaling. In contrast, inhibition of CFTR expression at E16 resulted in further expansion of β-galactosidase positive cell populations to the parenchyma (Fig. 2D). Thus, consistent with the results of Fig. 1, Wnt/β-catenin signaling patterns are dependent upon CFTR expression levels. Over expression facilitated the normal pattern for Wnt/β-catenin and antisense inhibition of CFTR resulted in an abnormal increase and distribution in foci of β-galactosidase positive cells.

Distribution of β-galactosidase expression in embryonic lungs. Immunohistochemistry was used to identify cells expressing β-galactosidase in Bat-gal mouse fetal lungs from either E16 (Panels A, C, & E) or E17 (Panels B, D, & F). 24 hours prior to harvest animals were treated with either AdCMVeGFP (control; panels A & B); AdCMVascftr (antisense CFTR; Panels C & D); Av1CF2 (CFTR; Panels E & F). 10 μm scale bar is presented in Panel F.

Developmental programming of PTHrP expression by CFTR

Based on the previously demonstrated relationship between mechanical stretch, Wnt signaling and PTHrP expression [17, 19, 20, 26] and our previous work on CFTR that has shown that it modulates stretch to influence gene regulation in the developing lung [7], we investigated the relationship between CFTR-dependent stretch and PTHrP levels.

Immunohistochemistry was used to visualize PTHrP expression at E17, the time when CFTR expression had the greatest effect on BAT-gal reporter expression (Fig. 1). In control animals low levels of PTHrP were detected in the developing parenchyma (Fig. 3, Panel A). In marked contrast, down-regulation of CFTR with the antisense construct resulted in a dramatic decrease in PTHrP immunostaining (Panel B), whereas CFTR over expression (Panel C) resulted in a significant increase in PTHrP expression in comparison to both control- and antisense CFTR-treated lungs (Panel C). Quantitative evaluation of PTHrP showed statistically significant differences between control-, antisense CFTR-, and CFTR-treated lungs (Panel D). Thus, there was a direct correlation between CFTR expression and PTHrP levels in the developing lung at E17.

PTHrP in lung development. Bat-gal mice were injected with either AdCMVeGFP (Panel A), AdCMVascftr (Panel B), or Av1CF2 (Panel C; Adenovirus CFTR) at E15 and tissues harvest at E16. Tissues were stained with DAPI (Blue), Phalloidin (Green), and immunofluorescent analysis of PTHrP (Red). Slidebook software was used for pixel counting of PTHrP in a series of slides (Panel D).

Discussion

CFTR is expressed at high levels during specific periods of lung organogenesis and expression subsequently decreases by 75 fold as the lung matures [27, 28]. This pattern of expression suggests a role for this gene in normal lung development. The finding that CFTR has a role in mechanical stretch which is necessary for lung organogenesis [7] provides a possible mechanism for this gene in lung development.

Specifically, our findings of a direct correlation between CFTR expression and PTHrP levels (Fig. 3) in developing lung and the inverse correlation with Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Fig. 1 &2) are consistent with the mechanical stretch-dependent development of surfactant production[29]. These data collectively reveal a possible mechanism for how a chloride channel, CFTR, could have a global effect on lung development. By directly effecting mechanical stretch necessary for generating lung complexity this chloride channel could have an essential role in normal lung organogenesis.

In the normal Bat-gal mouse lung Wnt expression peaked at a specific time (Fig. 1) in lung development that may be defined by the total induced stretch (Fig. 4, Arrow). If CFTR increases stretch as shown previously [7] and illustrated in Fig. 4, then one would predict that the slope of the change in stretch would be increased. Thus, Wnt expression would peak earlier for a shorter time and lower level. Antisense CFTR, however, would lower the slope of the stretch effect, prolonging Wnt activation and increasing its activity. Thus, the changes observed in Fig. 1 can be explained by a change in CFTR-dependent, stretch-induced regulation of Wnt. This interpretation is consistent with the previous work by the Torday and Rehan group showing the relationship between stretch and Wnt [19, 26]

Our previous studies examining the effects of in utero CFTR gene transfer on lung growth and development showed that over expression of CFTR resulted in increased bronchial cell differentiation and proliferation, decreased alveolar complexity, and increased stretch [7, 12]. In this paper we demonstrated that CFTR over expression increases PTHrP (Fig 3); and decreased CFTR expression dramatically increased Wnt signaling (Fig 1, 2). If one examines all these CFTR-dependent effects both previously published [7, 12, 13, 15, 22, 30] and current data provided here, CFTR, a chloride channel, has many, seemingly independent, affects on lung organogenesis. However, stretch was previously shown by Torday and Rehan [17, 19, 26, 29, 31] to correlate directly with PTHrP which controls a cascade in which lower PTHrP (from lower stretch) increases Wnt activation that leads to increased bronchial cell differentiation and proliferation and decreased alveolar complexity. Thus, it is possible to correlate all the effects seen independently by altering CFTR levels in the fetal lung with a direct effect of CFTR on stretch that then modifies the Torday-Rehan PTHrP-Wnt pathway for terminal differentiation of the lung. Initially, mechanical stretch promotes proximal airway development but with growth, distal airway differentiation results in decreased pressure and Wnt-dependent alveolar differentiation and complexity. Our results correlated with those of Torday and Rehan [17–20, 31–34] suggest that CFTR could play a central role in this process along with other genes that affect mechanical stretch including Rho kinase [35] and ENaC [36, 37].

Delineation of the exact role of CFTR in this process requires further investigation. However, several recent findings may suggest a mechanism. Treharne et al. [38] recently showed that CFTR function was linked to casein kinase 2, a rather promiscuous protein kinase. In addition, CFTR function is known to be associated with actin filaments [39, 40] and recent work has shown that a cAMP/protein kinase A-dependent annexin 2 S100A10 complex with CFTR also affects its function [41]. These observations provide increasing evidence that the CFTR gene product plays important roles beyond that of a chloride channel and that it is part of a complex of molecules within the cytoskeleton of the cell that have a high potential for kinase-mediated gene regulation. Therefore, we speculate that stretch of the cytoskeleton could be the signal to modulate CFTR function and mechanical stretch. Thus, CFTR could function as a mechanicosensor essential for lung organogenesis.

Conclusion

During late lung development CFTR probably acting through a mechanicosensory pathway regulates Wnt/β-Catenin signaling.

Methods

BAT-gal Wnt/β-Catenin Reporter Mice

Generation and characterization of the BAT-gal mice have been previously described [21]. E1 was defined as the day that the vaginal plug was observed.

In Utero Gene Transfer

In utero gene transfer used three first generation adenovirus vectors. Av1CF2 is a recombinant with the CFTR gene (Genetic Therapy, Inc), AdCMVascftr is an antisense CFTR construct previously described [22] and AdCMVeGFP with the green fluorescent protein gene (J. Kolls, Univ. Pittsburgh) was used as a control virus. All viruses were resuspended in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (DMEM) and injected into the amniotic fluid as described previously [23]. Fetuses were injected at gestation day E15, E16, or E17. Individual fetuses were injected with a final amniotic fluid virus concentration of 109 pfu/ml. All animals were harvested at 24 hours post-gene transfer.

Enzyme Assay

Beta galactosidase activity was measured using Applied Biosystems Galacto-Light Plus System (catalog # T1007). Lung tissues were disassociated in the supplied lysis solution, endogenous activity was lowered by heat inactivating for 50 minutes at 48°C and then measured in triplicate. Measurements were made using a tube luminometer (Monolight 2010). Protein concentrations were measured using Bio-Rad Dc Protein Assay (#500–0112).

Immunofluorescent Microscopy

Lung tissue fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde was embedded in Cryo-Gel and sectioned. Sections were stained with PTHrP (Santa Cruz, sc-20728) and the protein of interest was tagged with Alexa Fluor donkey anti-rabbit 568 (Molecular Probes, A-10042). Nuclei were stained with DAPI and actin was stained with Phalloidin 488 (Molecular Probes, A-12379).

Statistical methods

Image software SLIDEBOOK was used to capture images and then quantitatively evaluate pixel count. Blinded random fields from taken from 5 independent sections were used. Graph Pad Prism was used for statistic analysis (unpaired, T-test).

References

Featherstone NC, Jesudason EC, Connell MG, Fernig DG, Wray S, Losty PD, Burdyga TV: Spontaneous propagating calcium waves underpin airway peristalsis in embryonic rat lung. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2005, 33 (2): 153-160. 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0137OC.

Featherstone NC, Connell MG, Fernig DG, Wray S, Burdyga TV, Losty PD, Jesudason EC: Airway smooth muscle dysfunction precedes teratogenic congenital diaphragmatic hernia and may contribute to hypoplastic lung morphogenesis. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2006, 35 (5): 571-578. 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0079OC.

Ingber DE: Cellular mechanotransduction: putting all the pieces together again. Faseb J. 2006, 20 (7): 811-827. 10.1096/fj.05-5424rev.

Mucenski ML, Wert SE, Nation JM, Loudy DE, Huelsken J, Birchmeier W, Morrisey EE, Whitsett JA: beta-Catenin is required for specification of proximal/distal cell fate during lung morphogenesis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003, 278 (41): 40231-40238. 10.1074/jbc.M305892200.

Vogel V: Mechanotransduction involving multimodular proteins: converting force into biochemical signals. Annual review of biophysics and biomolecular structure. 2006, 35: 459-488. 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102013.

Haga JH, Li YS, Chien S: Molecular basis of the effects of mechanical stretch on vascular smooth muscle cells. Journal of biomechanics. 2007, 40 (5): 947-960. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.04.011.

Cohen JC, Larson JE: Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) dependent cytoskeletal tension during lung organogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2006, 235 (10): 2736-2748. 10.1002/dvdy.20912.

Cohen JC, Scott D, Miller J, Zhang J, Zhou P, Larson JE: Transient in utero knockout (TIUKO) of C-MYC affects late lung and intestinal development in the mouse. BMC developmental biology. 2004, 4: 4-10.1186/1471-213X-4-4.

Cardoso WV, Lu J: Regulation of early lung morphogenesis: questions, facts and controversies. Development (Cambridge, England). 2006, 133 (9): 1611-1624.

Sekhon HS, Keller JA, Proskocil BJ, Martin EL, Spindel ER: Maternal nicotine exposure upregulates collagen gene expression in fetal monkey lung. Association with alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002, 26 (1): 31-41.

Larson JE, Morrow SL, Delcarpio JB, Bohm RP, Ratterree MS, Blanchard JL, Cohen JC: Gene transfer into the fetal primate: evidence for the secretion of transgene product. Mol Ther. 2000, 2 (6): 631-639. 10.1006/mthe.2000.0209.

Larson JE, Delcarpio JB, Farberman MM, Morrow SL, Cohen JC: CFTR modulates lung secretory cell proliferation and differentiation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000, 279 (2): L333-41.

Morrow SL, Larson JE, Nelson S, Sekhon HS, Ren T, Cohen JC: Modification of development by the CFTR gene in utero. Molecular genetics and metabolism. 1998, 65 (3): 203-212. 10.1006/mgme.1998.2755.

Larson JE, Morrow SL, Happel L, Sharp JF, Cohen JC: Reversal of cystic fibrosis phenotype in mice by gene therapy in utero. Lancet. 1997, 349 (9052): 619-620. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61567-X.

Cohen JC, Morrow SL, Cork RJ, Delcarpio JB, Larson JE: Molecular pathophysiology of cystic fibrosis based on the rescued knockout mouse model. Molecular genetics and metabolism. 1998, 64 (2): 108-118. 10.1006/mgme.1998.2683.

Larson JE, Cohen JC: Improvement of pulmonary hypoplasia associated with congenital diaphragmatic hernia by in utero CFTR gene therapy. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006, 291 (1): L4-10. 10.1152/ajplung.00372.2005.

Rehan VK, Torday JS: Exploiting the PTHrP signaling pathway to treat chronic lung disease. Drugs Today (Barc). 2007, 43 (5): 317-331. 10.1358/dot.2007.43.5.1062665.

Torday JS, Rehan VK: Developmental cell/molecular biologic approach to the etiology and treatment of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatric research. 2007, 62 (1): 2-7. 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31806772a1.

Torday JS, Rehan VK: Up-regulation of fetal rat lung parathyroid hormone-related protein gene regulatory network down-regulates the Sonic Hedgehog/Wnt/betacatenin gene regulatory network. Pediatric research. 2006, 60 (4): 382-388. 10.1203/01.pdr.0000238326.42590.03.

Torday JS: Parathyroid hormone-related protein is a gravisensor in lung and bone cell biology. Adv Space Res. 2003, 32 (8): 1569-1576. 10.1016/S0273-1177(03)90397-8.

Echelard Y, Vassileva G, McMahon AP: Cis-acting regulatory sequences governing Wnt-1 expression in the developing mouse CNS. Development (Cambridge, England). 1994, 120 (8): 2213-2224.

Sekhon HS, Larson JE: In utero gene transfer into the pulmonary epithelium. Nat Med. 1995, 1 (11): 1201-1203. 10.1038/nm1195-1201.

Garrett DJ, Larson JE, Dunn D, Marrero L, Cohen JC: In utero recombinant adeno-associated virus gene transfer in mice, rats, and primates. BMC Biotechnol. 2003, 3 (1): 16-10.1186/1472-6750-3-16.

Cohen JC, Larson JE: Pathophysiologic consequences following inhibition of a CFTR-dependent developmental cascade in the lung. BMC developmental biology. 2005, 5 (1): 2-10.1186/1471-213X-5-2.

Torday JS, Rehan VK: The evolutionary continuum from lung development to homeostasis and repair. American journal of physiology. 2007, 292 (3): L608-11.

Broackes-Carter FC, Mouchel N, Gill D, Hyde S, Bassett J, Harris A: Temporal regulation of CFTR expression during ovine lung development: implications for CF gene therapy. Human molecular genetics. 2002, 11 (2): 125-131. 10.1093/hmg/11.2.125.

Marcorelles P, Montier T, Gillet D, Lagarde N, Ferec C: Evolution of CFTR protein distribution in lung tissue from normal and CF human fetuses. Pediatric pulmonology. 2007, 42 (11): 1032-1040. 10.1002/ppul.20690.

Sanchez-Esteban J, Tsai SW, Sang J, Qin J, Torday JS, Rubin LP: Effects of mechanical forces on lung-specific gene expression. The American journal of the medical sciences. 1998, 316 (3): 200-204. 10.1097/00000441-199809000-00009.

Larson JE, Cohen JC: Improvement of Pulmonary Hypoplasia Associated with Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia by In Utero CFTR Gene Therapy. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006

Torday JS, Sanchez-Esteban J, Rubin LP: Paracrine mediators of mechanotransduction in lung development. The American journal of the medical sciences. 1998, 316 (3): 205-208. 10.1097/00000441-199809000-00010.

Rehan VK, Dargan-Batra SK, Wang Y, Cerny L, Sakurai R, Santos J, Beloosesky R, Gayle D, Torday JS: A paradoxical temporal response of the PTHrP/PPARgamma signaling pathway to lipopolysaccharide in an in vitro model of the developing rat lung. American journal of physiology. 2007, 293 (1): L182-90.

Rehan VK, Sakurai R, Wang Y, Santos J, Huynh K, Torday JS: Reversal of nicotine-induced alveolar lipofibroblast-to-myofibroblast transdifferentiation by stimulants of parathyroid hormone-related protein signaling. Lung. 2007, 185 (3): 151-159. 10.1007/s00408-007-9007-0.

Rehan VK, Sugano S, Wang Y, Santos J, Romero S, Dasgupta C, Keane MP, Stahlman MT, Torday JS: Evidence for the presence of lipofibroblasts in human lung. Experimental lung research. 2006, 32 (8): 379-393. 10.1080/01902140600880257.

Moore KA, Polte T, Huang S, Shi B, Alsberg E, Sunday ME, Ingber DE: Control of basement membrane remodeling and epithelial branching morphogenesis in embryonic lung by Rho and cytoskeletal tension. Dev Dyn. 2005, 232 (2): 268-281. 10.1002/dvdy.20237.

Sheridan MB, Fong P, Groman JD, Conrad C, Flume P, Diaz R, Harris C, Knowles M, Cutting GR: Mutations in the beta-subunit of the epithelial Na+ channel in patients with a cystic fibrosis-like syndrome. Human molecular genetics. 2005, 14 (22): 3493-3498. 10.1093/hmg/ddi374.

Tavernarakis N, Driscoll M: Mechanotransduction in Caenorhabditis elegans: the role of DEG/ENaC ion channels. Cell biochemistry and biophysics. 2001, 35 (1): 1-18. 10.1385/CBB:35:1:01.

Treharne KJ, Crawford RM, Xu Z, Chen JH, Best OG, Schulte EA, Gruenert DC, Wilson SM, Sheppard DN, Kunzelmann K, Mehta A: Protein kinase CK2, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, and the deltaF508 mutation: F508 deletion disrupts a kinase-binding site. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007, 282 (14): 10804-10813. 10.1074/jbc.M610956200.

Chasan B, Geisse NA, Pedatella K, Wooster DG, Teintze M, Carattino MD, Goldmann WH, Cantiello HF: Evidence for direct interaction between actin and the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Eur Biophys J. 2002, 30 (8): 617-624. 10.1007/s00249-001-0188-9.

Cantiello HF: Role of actin filament organization in CFTR activation. Pflugers Arch. 2001, 443 Suppl 1: S75-80.

Borthwick LA, McGaw J, Conner G, Taylor CJ, Gerke V, Mehta A, Robson L, Muimo R: The formation of the cAMP/protein kinase A-dependent annexin 2 S100A10 complex with cystic fibrosis conductance regulator protein (CFTR) regulates CFTR channel function. Molecular biology of the cell. 2007, 18 (9): 3388-3397. 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0126.

Jarvinen E, Salazar-Ciudad I, Birchmeier W, Taketo MM, Jernvall J, Thesleff I: Continuous tooth generation in mouse is induced by activated epithelial Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006, 103 (49): 18627-18632. 10.1073/pnas.0607289103.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Brady Foundation to J.E.L and J.C.C. and NIH R01 DK073191 to K.I.T.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

JCC, EK, DL, and K–IT are responsible for performing the required laboratory work. JCC, JEL, and K–IT developed the experimental framework and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Cohen, J.C., Larson, J.E., Killeen, E. et al. CFTR and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in lung development. BMC Dev Biol 8, 70 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-213X-8-70

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-213X-8-70