Abstract

Background

Rybp (Ring1 and YY1 binding protein) is a zinc finger protein which interacts with the members of the mammalian polycomb complexes. Previously we have shown that Rybp is critical for early embryogenesis and that haploinsufficiency of Rybp in a subset of embryos causes failure of neural tube closure. Here we investigated the requirement for Rybp in ocular development using four in vivo mouse models which resulted in either the ablation or overexpression of Rybp.

Results

Our results demonstrate that loss of a single Rybp allele in conventional knockout mice often resulted in retinal coloboma, an incomplete closure of the optic fissure, characterized by perturbed localization of Pax6 but not of Pax2. In addition, about one half of Rybp-/- <-> Rybp+/+ chimeric embryos also developed retinal colobomas and malformed lenses. Tissue-specific transgenic overexpression of Rybp in the lens resulted in abnormal fiber cell differentiation and severe lens opacification with increased levels of AP-2α and Sox2, and reduced levels of βA4-crystallin gene expression. Ubiquitous transgenic overexpression of Rybp in the entire eye caused abnormal retinal folds, corneal neovascularization, and lens opacification. Additional changes included defects in anterior eye development.

Conclusion

These studies establish Rybp as a novel gene that has been associated with coloboma. Other genes linked to coloboma encode various classes of transcription factors such as BCOR, CBP, Chx10, Pax2, Pax6, Six3, Ski, Vax1 and Vax2. We propose that the multiple functions for Rybp in regulating mouse retinal and lens development are mediated by genetic, epigenetic and physical interactions between these genes and proteins.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The vertebrate eye is a complex neurosensory organ. Normal function of the eye requires precise spatial organization and interaction between individual tissues to respect the laws of optics. During embryonic development, reciprocal inducing events result in the formation of the lens and the retina that originate from progenitor cells located in the head surface ectoderm and neuroepithelium of the ventral diencephalon, respectively (see reviews:[1, 2]). Abnormal lens and retinal development can cause isolated or widespread ocular abnormalities that can obstruct vision at different levels and lead to blindness (reviewed in [3]).

Between embryonic day E9.5 and E11.5 of mouse development, the optic vesicle undergoes dorso-ventral patterning of the neuroepithelium followed by its invagination to form the bilayered optic cup [4]. This process gives rise to the optic fissure, allowing blood vessels originating from the vascular mesoderm to enter the developing eye. By E13.5, the nasal and temporal retina on either side of the choroid fissures fuses around the optic nerve axons and blood vessels. Failure of this closure results in a specific developmental abnormality, called ocular coloboma. Ocular coloboma is often seen in association with severe neurological and/or craniofacial abnormalities [5] or can develop as an isolated condition [6].

Lens differentiation at E12.5 is marked by cellular elongation of the lens cells forming the posterior part of the lens vesicle [7]. Differentiating lens fiber cells upregulate expression of various classes of structural proteins including crystallins, intermediate filament bead proteins, and cytoskeletal, membrane, and channel proteins. Abnormal lens fiber cell differentiation disrupts lens homeostasis leading to precipitation of lens proteins resulting in lens opacification and perturbed vision (see review [8]).

At the molecular level, a significant number of genes involved in the control of eye development also regulate brain development [9]. The most notable classes are homeobox genes such as Lhx2, Otx2, Pax6, Rx and Six3, and the basic helix-loop-helix genes Math5, Neurod1 and Neurog2. In contrast, other genes play specialized roles during lens (e.g., Foxe3, Mab21like1, c-Maf, Pitx3, Sox1 and Hsf4) or retinal (e.g., Chx10, Mab21like2, Six6/Optx2, Vax1, Vax2) development [10, 11]. Several global regulatory genes are also integral to normal ocular development. For example, Brg1 [12], Snf2h [13] and Sox2 [14] regulate embryonic development prior to the organ formation. Later, Brg1 and Snf2h are thought to regulate retinal [15] and lens development [16], and Sox2 is required for lens placode formation [17] and optic cup formation [18]. AP-2α [19, 20], pRb [21] and its partners, the E2Fs [22] play roles in both retinal and lens differentiation.

Rybp (RING1 and YY1 binding protein) is an evolutionarily conserved protein with a zinc-finger motive that was identified first as an interacting partner for the Polycomb group protein Ring1A [23]. Polycomb group (PcG) proteins function as transcriptional repressors acting part through histone modification, and are believed to be important regulators of organogenesis and cell lineage specification [24, 25]. Recent studies in Drosophila have shown that Drosophila RYBP depends upon PcG proteins to repress transcription, suggesting that Rybp could be classified as a PcG protein itself [26]. Other studies have demonstrated Rybp's interaction with DNA binding transcription factors [27–29] as well as with apoptotic [30] and ubiquitinated proteins [31]. Although the precise molecular function of Rybp is not yet known, these interactions suggest that Rybp may be a multifunctional developmental regulator. Indeed, we have shown recently that the Rybp is required both for early mouse development and for proper brain formation. Specifically a dose-dependent role in the central nervous system (CNS) for Rybp was uncovered: haploinsufficiency in the subset of embryos caused an exencephalic phenotype due to imperfect closure of the neural tube [32].

Given established parallels between brain and eye development, we hypothesized that Rybp may also play a role in ocular development. Here we determined Rybp protein localization patterns in the murine eye and analyzed the function of Rybp in four mouse models representing reduced or increased Rybp gene dosage. These studies have shown that aberration in the normal protein levels of Rybp can result in retinal coloboma, abnormal lens and anterior eye development, and corneal neovascularization.

Results

Rybp is expressed in multiple tissues of the mouse embryonic eye

In previous work, we reported the localization of Rybp in the developing CNS [32]. The common embryonic origin of the brain, lens, and retina from the primitive ectoderm prompted us to determine the protein localization of Rybp during mouse ocular development (Fig. 1). At E10.5, Rybp staining first strongly marked the head surface ectoderm surrounding the invaginating lens placode (Fig. 1A). Weak, speckled expression was also seen beneath the surface ectoderm, in the periocular mesenchyme, and throughout the emerging optic cup (Fig. 1A). From E11.5, Rybp appeared both in the anterior cells of the lens vesicle and in the nuclei of the elongating primary lens fiber cells (Fig. 1B). Similar to the lens, speckled expression was also evident in the optic cup, with a higher density of positive cells towards the ventral and marginal portion (Fig. 1B). Expression of Rybp in the hyaloid plexus was also detected (Fig. 1B). With progressive development, expression of Rybp persisted in the cells of the hyaloid cavity (Fig. 1C, D) and the head surface ectoderm. Between E14.5 and E16.5, Rybp localized in the differentiating secondary fiber cells of lens (E16.5; Fig. 1C and 1E) and in the ventral part of the neuroretina (E16.5; Fig. 1C, F). At E16.5 Rybp was also detected in the lens epithelium (Fig. 1C, G). In the cornea, Rybp was expressed in the corneal epithelium and some cells of the corneal stroma (Fig. 1G). Rybp displayed non-uniform weak staining in the cells of the optic nerve and stronger staining in the perioptic mesenchyme (Fig. 1H). One marked change in the expression pattern of Rybp during mouse eye development is that its widespread expression in undifferentiated cells of the retina becomes restricted to a layer-specific expression profile marking the gradually emerging ganglion (GCL) and inner nuclear (INL) cell layers (Fig. 1I–L). Rybp's expression is robust in the ganglion cell layer of the differentiating retina, but strong staining is also visible in the INL and in a few cells of the future photoreceptor layer of the neuroretina (Fig. 1L).

Rybp localization during prenatal mouse ocular development. (A-H) Sagittal sections were immunostained for Rybp (brown) and counterstained lightly with hematoxylin (purple) at E10.5 (A), E11.5 (B) and E16.5 (C-H). Higher-magnification of areas stained with the Rybp antibody indicated in (C) are shown in panels D-G. (I-L) Panels show the gradual increase of Rybp expression in the developing neural retina at E10.5 (I), E11.5 (J), E13.5 (K) and E18.5 (L). C; cornea, E; embryonic, GCL; ganglion cell layer, INL; inner nuclear layer, L; lens, NR; neuroretina, ON; optic nerve, PM; periocular mesenchyme, SE; surface ectoderm, OC; optic cup. Magnifications: A (×460); B(×320); C(×250); D(×800); E-H(×400); I(×630); J(×460), K(×320); L(×250).

Next, we analyzed the localization of Rybp in two day (P2, Figs. 2A,C,E,G), and twenty one day old (P21, Figs. 2B,D) mouse eyes. In the postnatal P2 retina, Rybp showed intense staining in the GCL and in the differentiating INL of the retina (Fig. 2A). At P21, Rybp still was expressed in the GCL and in the INL, specifically in its dorsal part likely coincident with the bipolar and horizontal cell layers (Fig. 2B). Although Rybp was detected in the early stages of primary lens fiber cell development (Fig. 1B), in the more mature lens its expression was attenuated both in fully elongated primary lens fiber cells and in the lens epithelium (Figs. 2C and 2D). However, strong expression of Rybp in the lens was seen in the transitional zone where the secondary lens fiber cells are formed (Figs. 2C and 2D). At P2.0, Rybp was expressed in the majority of lens epithelial cells, and sporadic expression also was observed in the corneal epithelium, stroma, and basal membrane (Fig. 2E). By P21.0, Rybp is no longer expressed in the lens epithelium but still is weakly expressed in the corneal epithelium (Fig. 2F). Finally, Rybp was strongly expressed postnatally in the connectiva (Fig. 2G), and uniform localization of Rybp was observed around the newborn optic nerve (Fig. 2H). This dynamic and cell-type restricted expression pattern of Rybp (Figs. 1 and 2) raises the possibility that Rybp may have specific functional roles in the generation/maintenance of particular cell types during mammalian eye development.

Rybp localization in the postnatal mouse eye. Sagittal sections of the eye at the level of the optic nerve at P2.0 (A, C, E, G, and H), and P21 (B, D, and F) were immunostained for Rybp. Shown are the retina (A, B), lens (C, D) cornea (E, F), connectiva (G) and optic nerve (H). C; cornea, Ep; corneal epithelium, GCL; ganglion cell layer, INL; inner nuclear layer, L; lens, LE; lens epithelium, ON; optic nerve, PLF primary lens fiber cells, T; transitional zone P; postnatal day. Magnification: (320×)

A subset of the Rybp+/-embryos exhibits retinal coloboma

Previously we reported that a subset of Rybp heterozygous null embryos exhibited perturbed brain development including forebrain overgrowth and exencephaly [32]. As the retina forms from the forebrain, we next examined the possibility of aberrant eye development in these animals. We found that 32% (6/19) of Rybp+/- exencephalic mice examined at several stages of development (from E12.5 to postnatal stages) showed retinal/optic nerve coloboma (compare Fig. 3A and 3B). Colobomas of this type often are caused by an incomplete closure of the optic fissure that occurs normally at E13.5 [33]. Rybp+/- colobomas were observed both bilaterally and unilaterally. In addition, Rybp+/- eyes had thickened neuroretinas, their lenses were ventrally rotated and misplaced within the eyeball (see Fig. 3B in comparison to Fig. 3A). The optic nerve was also frequently regressed (Fig. 3F). One possible explanation for the development of colobomas is that the decreased level of Rybp in the mutant retinas influences the normal distribution of regulatory proteins such as Pax6 [34–36] or Pax2 [33, 37, 38]. Both Pax6 and Pax2 have been shown to be essential for proper closure of the optic fissure. Accordingly, we tested whether immuno-localization of Pax6 and Pax2 was affected in the mutant Rybp eyes. Normally, Pax6 protein is localized in the ventral side of the retina but disappears from the developing optic nerve after E12.0 in wild-type animals [39]. In the Rybp mutant embryos, Pax6 expression spreads across the entire thickness of the retina, expanding to its margin (Figs. 3C, D). In contrast, the localization of Pax2 in mutant eyes were unchanged (Fig. 3E compare to 3F).

Retinal coloboma in Rybp +/- mouse embryo. (A-B) Hematoxylin and eosin- stained coronal sections of normal (A) and Rybp heterozygous null (B) eyes at E14.5. The neuroretina of the mutant eye is thickened and fails to close leading to the formation of coloboma (B; arrowhead). (C-D) Immunolocalization of Pax6 in wild type (C) and mutant (D) eyes. Pax6 is normally expressed in the ventral side of neuroretina. In the mutant eyes it shows broader expression in the retina and it is also more posteriorly positioned in the transition zone of the lens (C compare to D). (E-F) Immunolocalization of Pax2 in wild type (E) and mutant (F) eyes. L; lens, NR; neuroretina, ON; optic nerve, V; ventral, T; transitional zone. HE; hematoxylin and eosin. Magnifications: A-D(×320); E-F(×460)

The proper ratio between neural progenitor and postmitotic neuronal cell types is important for normal retinal development and disturbed morphogenesis of this process can lead to colobomas. [40]. Accordingly, we investigated whether the ratio between early- and late-born neurons changed in the mutant retinas exhibiting the coloboma phenotype. In the prenatal mutant retina, expression of specific neuronal cell fate markers was similar to the expression of these markers in the retina of control mice. These included Tuj1 (marks early neural cell types; Fig. 4A,B), NeuN (postmitotic, marks late neuronal cell types; Fig. 4C, D) and nestin (marks neural progenitor cells; Fig. 4E, F). The apparent normal distribution of these neuronal markers shows that the neuronal cell differentiation is not affected in the Rybp mutant retinas and probably is not the direct cause of the failure of optic fissure closure.

Progenitor cell fate is not changed in the mutant retinas of the Rybp heterozygous eyes. Wild type (A, C, E) and Rybp heterozygous null eyes exhibiting retinal coloboma (B, D, F) were stained with TUJ1 (A, B), NeuN (C, D) and Nestin (E, F) at E14.5. (A-B) TUJ1 staining, marking early neuronal cell types including ganglion cells of the retina, is comparable in the wildtype and mutant mice. (C-D) Similarly, NeuN, a postmitotic neural marker, shows no significant alteration in the mutant retinas. (E-F) The distribution of nestin, an intermediate filament marker for neural progenitor cells, is not affected in the mutant retinas. L; lens, NR; neuroretina, Magnifications: (×460)

Rybp-/- <-> Rybp+/+ chimeric embryos show a series of eye defects

Early lethality of Rybp -/- embryos [32] prevented our analysis of the effect of a complete loss of Rybp during eye development. However, chimeric mice (n = 90) have been generated from Rybp homozygous null -/- and wild type (+/+) ES cells, and 20% of them showed low overall contribution of Rybp -/- ES cells and displayed forebrain abnormalities [32]. Half of the chimeric embryos (examined between E9.5 and E14.5) with brain abnormalities also showed eye defects similar to those described above for the Rybp+/- embryos. These included retinal colobomas (Figs. 5A and 5B), and defects in lens formation (compare Figs. 5D to 5C and 5F to 5E). In addition, in an E13.5 chimera, the separation between the lens epithelium and the surface ectoderm was compromised (compare Fig. 5H to 5G). Our findings again indicate that normal lens and retinal development cannot occur in the context of suboptimal Rybp dosage.

Multiple ocular abnormalities in Rybp-/- <-> Rybp+/+ chimeric embryos. (A-B) Whole mount eyes from E13.5 wild type (A) and chimeric (B) embryos. The normal eye is symmetrical, while in the chimeric eye the chorioid fissure fails to close, leaving a large coloboma (arrowhead). (C-F) Histology of coronal sections of E13.5 wild type (C, E) and chimeric (D, F) eyes. Higher-magnification views of areas indicated in (C) and (D) are shown in (E) and (F), respectively. In the chimeric embryos, the eyes are rotated, lens development is delayed and overall lens size is reduced, and the retina is asymmetric with thickening on one side (F; arrowhead). (G-H) At E13.5 in the normal eye there is a mesenchymal cell layer between the SE and the LE (G; black arrowhead). In the chimeric eye, the lens epithelium is continuous and mixed with the mesenchyme and the surface epithelium (H; black arrowhead). H; hyaloid cavity, L; lens, LE; lens epithelium, NR; neuroretina, SE; surface ectoderm. Magnification: A-B (×120); C-D (×60); E-F (160×); G-H (×400)

Overexpression of Rybpresults in lens, retinal and corneal defects

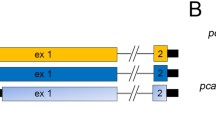

Next we employed a conditional ectopic overexpression strategy [41] to assess the effects of Rybp overexpression in the lens. First we introduced an inducible Rybp – green fluorescent protein (EGFP) fusion gene into the mouse genome (ROSA26-RYBP/EGFP mice; Fig. 6A). Proteins were extracted from the targeted ES cell lines (ROSA26-RYBP/EGFP cell line) prior to and following Cre induction (ROSA26-RYBP/EGFP; Cre cell line), and the expected 66 kDa Rybp/EGFP fusion protein was observed (Fig. 6B). To demonstrate that this fusion protein is functional and can bind to Ring1A as described earlier [23], the excised cells (ROSA26-RYBP/EGFP; Cre cell line) were transiently transfected with Flag-tagged Ring1A, and lysates were immunoprecipitated with either RYBP or GFP antibodies and blotted with a Flag antibody. As expected, the RYBP/EGFP fusion protein was found together with Ring1A in vivo (Fig. 6C).

Lens-specific and ubiquitous expression of RYBP/EGFP fusion protein. (A) Scheme illustrating the strategy used to generate a Cre recombinase-mediated conditional ectopic Rybp allele by targeting the ROSA26 locus (for details, see Methods). The position of the hybridization probe (dot) and restriction enzyme EcoRV (arrows) used for detecting the correct homologous integrants by Southern blotting is shown. The 5' probe used detects an 11 kb wt band and a 3.8 kb targeted band, due to the presence of an extra EcoRV site in the targeted allele. The exons shown as open boxes. Cre: Cre-recombinase, EGFP; enhance green fluorescent protein, Neo; neomycin phosphotransferase. (B) Western blotting analysis showing the expression of the RYBP/EGFP fusion in lysates of cells that have been exposed to Cre recombinase. Lane 1, lysates from ROSA26 knock-in ES cells prior to Cre exposure (-Cre); lane 2, lysates from Rosa26 knock-in ES cells after Cre exposure (+Cre); lane 3, lysates from ES cells transfected with an RybpFlag construct, as a positive control. The blot was probed with the anti-Rybp antibody. (C) Ectopically expressed Rybp can associate with Ring1A. Lanes 1–2: Cells lysates of transfected ES cells blotted with anti-Flag antibody showing that both Ring1aFlag (Lane 1) and Maf1Flag (Lane 2) strongly expressed in the transfected cells; Lane 1, Cells transfected with Ring1AFlagconstruct., Lane 2, Cells transfected with Maf1Flagconstruct. Lane 3–4: Cells transfected with either Ring1AFlag(Lane 3) or with MAF1Flag(Lane 4), then immunoprecipitated with Rybp and blotted with anti-Flag antibody. Lane 3 shows the 57 kdDa Ring1AFlag fusion protein as the result of the association with the RYBP/EGFP fusion protein. Maf1 cannot bind Rybp (Lane 4). (D) P1 eyes harvested from double transgenic (ROSA26-RYBP/EGFP; αA-crystallin/Cre mice) and wildtype (WT) animals shown in dark field and fluorescence. (E) Lens specific over-expression of the RYBP/EGFP fusion protein in newborn (P2) lenses. EGFP immunohistochemistry shows the overexpression of the transgene in the ROSA26-RYBP/EGFP; αA-crystallin/Cre lens (TG). The wild-type lens shows only background staining (WT). (F) Bright-field and dark-field pictures of E11.5 littermates. All embryos that genotyped double transgenic for ROSA26-RYBP/EGFP;β-Actin/Cre also exhibited detectable EGFP fluorescence (TG) when compared to wildtype (WT) littermates. Magnification: D (×40); E (×10)

The ROSA26-RYBP/EGFP mice were crossed with two different reporter mouse lines and the proper expression of the fusion protein was confirmed by fluorescent microscopy: lens specific expression was seen for the ROSA26-RYBP/EGFP;αA-crystallin/Cre double transgenics (Fig. 6D) and ubiquitous expression for the ROSA26-RYBP/EGFP;β-Actin/Cre double transgenics (Fig 6F). Aberrant lens morphology of the ROSA26-RYBP/EGFP; αA-crystallin/Cre mice is shown in Fig. 7. Although the P2 embryonic lenses showed only subtle abnormalities in fiber cell morphology (7A–B), older mice developed severe opacities of the lens resulting in a collapse of lens fiber mass (Figs. 7C–D). Eyes from ROSA26-RYBP/EGFP; β-Actin/Cre mice were examined at embryonic (E16.5, E18.5), postnatal (P1–P4, P7, P14, P21) and adult stages (2, 3, 6 month) (Fig. 8, and data not shown). This ubiquitous overexpression of RYBP/EGFP led to the abnormal formation of a number of ocular tissues. The most frequent phenotype seen (in 35% of the mice) was neovascularization of the corneas (compare Fig. 8C–D to 8A–B). These structural changes were visible at postnatal stages (P7-21) during which the stromal layer thickened. When hemizygous mice were mated to obtain mice homozygous for the RYBP/EGFP transgene, the penetrance of the phenotype increased to 80%. Small vessels were apparent in the stroma of the cornea under bright field microscopy, and by 2–4 months postnatal, gross corneal neovascularization was visible (data not shown). Electron microscopy studies showed that the capillaries are already present at birth in the transgenic corneas (Fig. 8E, F). This was further supported by immunohistochemistry using an anti-CD34 antibody which marked the newly formed vessels of the mutant corneas (data not shown). Aside from neovascularization, other observed ocular phenotypes included irregular folding of the retina, retinal coloboma, defects in anterior eye development (absence of the vitreous body, absence of the anterior chamber), and lens opacification during later adulthood (Fig. 8G,H and data not shown). In summary we have developed transgenic mouse models in which expression of Rybp in the lens disrupted normal fiber cell differentiation and ubiquitous expression of Rybp resulted in corneal neovascularization and defects in the anterior eye development. These models suggest that normal eye development is sensitive for the proper dose of Rybp and that improper dosage of Rybp causes multiple eye abnormalities.

Abnormal lens development in the lens-specific Rybp transgenic mice. (A-D) Histological appearance of wild type (A, C) and ROSA26-RYBP/EGFP; αA-crystallin/Cre transgenic (B, D) lenses at early postnatal (P2) development (A, B) and adulthood (3 month) (C, D). (A, C) Wild type eyes with normal morphology of the lens epithelium and fiber cells. (B, D) Transgenic eyes showing cortical inhomogeneity as a sign of developing cataract and impaired lens development (B). Lenses of adult transgenic mice (3 month) show progressed cataractous morphology (D). CA; cataract, L; lens, LE; lens epithelium, T; transitional zone, TG; transgenic, WT; wild type; P; postnatal. Magnification: A-B (×160); C-D (×250); E-F (×120)

Genes with altered expression level in the Rybptransgenic lenses

As a first attempt to elucidate the molecular basis of abnormal lens fiber cell differentiation of the ROSA26-RYBP/EGFP; αA-crystallin/Cre mice (Figs 7, 8), we performed expression analysis of the genes involved in this process including major lens structural proteins, selected cell adhesion molecules, and major transcription factors implicated in lens development (Fig. 9). Total RNA from P1 transgenic and control lenses was used to synthesize cDNA, and quantitative RT-PCR was performed. The expression level of both Rybp and EGFP mRNA was increased 16-times compared to the non-transgenic control as expected. From the major lens structural proteins, the Cryba4 transcript showed a seven-fold reduction in transgenic lenses, while the expression of other crystallins and filensin was unchanged. From the tested cell adhesion molecules, α6-integrin mRNA level was five-times reduced while other integrins (α5- and β1-integrins) remained unchanged. Among tested transcription factors, AP-2α mRNA level was 30-times and Sox2 was 12-times elevated. The level of transcription factors Pax6, Prox1, MafA, MafB and c-Maf did not change significantly in the ROSA26-RYBP/EGFP; αA-crystallin/Cre lenses. These results further confirm that normal lens development depend on the Rybp gene dosage. RNA microarray studies may need to be conducted in the future to provide further insight into which membrane proteins, gap junctions and β/γ-crystallins are being affected.

Corneal neovascularization and irregular retinal development in ubiquitous Rybp transgenic mice. (A-F) Neovascularization of the ROSA26-RYBP/EGFP;β-Actin/Cre transgenic corneas in adult (2-month old) mice. Sagittal sections from wild type (A, B) and transgenic eyes (C, D) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin; boxes in panels A and C show areas magnified in panels B and D, respectively. The appearance of vessels (arrowheads in panel D) in the stroma of transgenic mice only is indicative of corneal neovascularization. The epithelium of the transgenic mice is also disorganized (D; open arrowhead). (E-F) Electron micrographs showing the corneal stroma next to the corneal epithelium in transgenic (Tg) and wild-type (Wt) animals at three weeks of age. While the stroma of the wild-type animal is not vascularized, a capillary (Ca) is seen close to the corneal epithelium in the transgenic animal. (G-H) Abnormal retinal folding and colobomas in newborn β-Actin/RYBP Tg mice (H) in comparison to normal retina in controls (G). C; cornea, Col; coloboma, E; epithelium, Ep; corneal epithelium; L; lens, NR; neuroretina, WT; wild type, S; stroma, TG; Transgenic. Magnification: A, C (×200); B, D (×460); G-H (×160)

Discussion

Rybp encodes an essential regulatory protein involved in early post-implantation development of the mouse embryo. In addition, Rybp plays important roles in organogenesis as evidenced by disrupted development of the forebrain found both in Rybp heterozygous null and chimeric embryos [32]. Here we characterized the protein localization and in vivo function of Rybp in another organ – the developing mouse eye. We show that Rybp is required for normal retinal and lens development, and may also be involved in the formation of the anterior eye segment.

Our previous work revealed that during CNS development, Rybp is predominantly localized in postmitotic neurons and differentiated cell types of the developing mouse embryo [32]. In the present study, we show that in the developing mouse eye, Rybp also becomes robustly made in the differentiating layers of the neuroretina including the ganglion and inner nuclear layer cells. This suggests once again a possible role for Rybp in cell cycle exit or the commitment to differentiation. Gaining further insight into the precise cellular role of Rybp during mouse ocular development likely requires a conditional mutant version of the gene where Rybp can be eliminated in specific cell lineages or at specific time points of embryonic development.

The major phenotypic malformation observed in all Rybp mouse models (heterozygous, chimeric and transgenic, see Table 1) was the failure of the closure of the optic fissure, retinal coloboma. Morphological analysis of embryonic eyes showed that 32% of Rybp deficient (heterozygous) and 50% of chimeric mice have eye coloboma in conjunction with brain defects, but coloboma was also seen in the Rybp transgenic mice that did not display obvious brain defects. A number of mammalian genes encoding transcription factors (BCOR, CBP, Chx10, Cited2, c-Maf, Foxg1, Pax2, Pax6, Ptch, Six3, Ski, Vax1 and Vax2), signaling molecules (Jnk1, Jnk2 and Shh), or members of the retinoic acid pathway have been associated with coloboma [5]. Our study describes Rybp as a novel gene associated with coloboma. While the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying this condition are still poorly understood, they likely involve perturbations in cell adhesion, cell shape, cell proliferation, cell death, and/or the extracellular matrix.

Aside from the retinal colobomas, a wide range of lens abnormalities were found in the Rybp mouse models. In both Rybp heterozygous and chimeric eyes, ventral rotation of the lens was found in association with coloboma (see Fig. 3 and 5). A similar phenotype has been reported for Otx mutant mice [42]. Lenses of Rybp chimeric embryos showed abnormal separation of the lens vesicle from the surface ectoderm (Fig. 5), a condition found in Pax6 heterozygous [43] and Foxe3 homozygous [44] mouse embryos. Transgenic lenses overexpressing Rybp developed abnormally differentiated lenses at birth (if not earlier), and this condition further deteriorated with age resulting in a total collapse of the lens fiber mass (see Fig. 7). This demonstrates that high level of Rybp disrupts normal fiber cell differentiation and maturation. Similar phenotype was observed when AP-2α transcription factor, individual E2Fs or growth factors were overexpressed in lens specific manner ([19, 45], see review [46]). Whether excess of Rybp interferes with adhesion and migration (like AP-2α), cell cycle (like E2Fs), terminal differentiation (like TGFβ) of secondary fiber cells or acts via completely different mechanisms, requires further studies. Indeed, RYBP was shown to be involved in specification of function within the family of E2F transcription factors in cell culture systems [28] however this has not been investigated in vivo during lens fiber cell differentiation.

Ubiquitous overexpression of Rybp caused similar lens defects and additionally led to corneal neovascularization (see Fig. 8). Genes such as VEGF, FGF2 and MMP-2 have already been associated with corneal neovascularization [47–50]. A possible connection between Rybp and angiogenesis warrants further investigation, especially in light of the observation that during embryonic development Rybp is expressed in hyaloid vessels and in the endothelium of blood vessels outside of the eye (Fig. 1; Pirity and Schreiber-Agus, unpublished data).

The variable penetrance of the phenotypes may indicate that expression and/or function of the retained wild type Rybp allele is being modified differentially in affected or non-affected animals. This is also supported by our previous observation that the penetrance of the exencephaly, a previously described heterozygous semipenetrant phenotype, was influenced by genetic background [32]. Indeed the phenomenon "semi-penetrance" is a common observation in genetically-engineered mice.

One potential molecular mechanism for abnormal eye development in Rybp mice could relate to Rybp's role in Polycomb group protein transcriptional regulation [23]. Polycomb proteins function in multiprotein complexes to regulate expression of homeotic and other regulatory genes during embryonic development [51–57] and also in eye development [58, 59]. Notably, in our limited gene expression studies using a candidate approach (Figure 9), several key eye regulators were found to be significantly affected in the Rybp transgenic lenses examined, including Sox2 and AP-2α (see also [60, 18, 19, 61]) as well as were some of the crystallins [62]. Moreover, Pax6 localization in retina and lens appears affected in the Rybp heterozygous null mice (Figure 3). Taken together, our findings suggest that Rybp may be regulating the expression of other developmental regulators, whose altered levels in the Rybp mouse models could be causal to the observed phenotypes. Further studies are necessary to determine whether Rybp directly regulates these (and other) genes, and whether this regulation occurs via the interaction of Rybp with Polycomb group transcriptional repressors. Interestingly, the abnormal anterior eye formation of Ring1-deficient mice, which is exacerbated in compound YY1+/-Ring1-/- mice, is similar to what we have observed in the Rybp mutant mice ([59] and Fig. 7H). Since both YY1 and Ring1A interact with Rybp and with other class II PcG proteins, it is possible that these proteins functionally interact to orchestrate normal vertebral eye development.

Conclusion

Collectively, the present work provides the first in vivo evidence for a role of the Polycomb group binding protein Rybp in mouse eye development and disease. Further studies need to address the molecular basis of this role and to determine how Rybp functionally relates to other known regulators of ocular processes.

Methods

Es cell injections, mouse breeding, husbandry and genotyping

ES cell injections, mouse breeding, husbandry, and genotyping of the Rybp knockout colonies was as previously described [32]. Chimeric embryos were generated by microinjecting Rybp-/- R1 ES cells (129/Sv × 129-Cp; [63]) into blastocysts derived from wild-type (Rybp+/+) mice (C56/BL6), as described previously [32]. The αA-crystallin/Cre transgenic mice were a kind gift of M.L. Robinson (Columbus, Ohio, USA); [64]. Analysis of the Cre-mediated recombination pattern in the αA-Cre line was performed by mating with the ROSA26 reporter line (Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1Sor) as described [65]. The β-Actin/Cre transgenic mice (FVB/N-Tg(ACTB-cre)2Mrt/J) line MRL [66] were purchased from Jackson laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA). Cre mice were crossed with the Rybp transgenic mice (see next) to obtain F1 Rybp transgenic mice (FVB).

Mice were housed in a 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle and maintained in the animal facility at AECOM in accordance with institutional guidelines. Noon of the day the vaginal plug was observed was considered E0.5 of embryogenesis. For genotyping targeted ES cell colonies/mice, EGFP Primers: A, (5'-aagttcatctgcaccaccg-3') and B, (5'-tgctcaggtagtggttgtcg-3') were used as described. The genotypes were determined by PCR analysis on DNA extracted from the tail or yolk sac.

Rybpconditional transgenics

The strategy used to generate a Cre recombinase-mediated conditional ectopic Rybp allele by targeting the ubiquitous ROSA26 locus is shown on Figure 6. The ROSA26 locus (referred to as an R26 knock-in) was targeted with a floxed neo cassette followed by an RYBP/EGFP fusion. To generate the RYBP/EGFP fusion, the Rybp open reading frame (ORF) was amplified with primers A (5'-gcacgtcgaccagcccgtccatgaccatgg-3') and B (5'-ctctggatccgaaagattcatcattcactgc 3') and cloned into pEGFP-N3 with NheI/SalI. The Rybp/EGFP fusion was transferred to pBigT [41] with NheI/Not1, and then the Rybp/EGFP together with the floxed neomycin cassette was cloned into the pROSA26 vector [41] with AscI/PacI. Rybp transgenic ES cell lines were generated by electroporating linearized targeting vector into R1 ES cells [63] as described in 96 clones resistant to G418 (Gibco, 300 μg/ml) were selected, and screened by genomic Southern blot hybridization on DNA digested with EcoRV as previously described [41]. Two targeted clones were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts and produced germ-line chimeras (ROSA26-RYBP/EGFP mice) [67]; mice carrying the targeted allele were genotyped by the PCR as described [41]. Male chimeras were mated with ICR females, and their agouti offspring were tested for transmission by tail PCR and blotting. Animals heterozygous for the mutation were bred with corresponding Cre transgenic lines and analyzed for the phenotype. Non-transgenic littermates were used as controls for all experiments. Heterozygous transgenic progeny were mated to maintain the allele. All analyses were performed on a mixed (129 × ICR) background and mutant mice were analyzed in comparison to their wild-type littermates.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

All embryos were dissected in PBS, fixed overnight in PBS buffered 4% paraformaldehyde, and paraffin-embedded sections (6 μm) were mounted for staining. For immunohistochemistry, deparaffinized and rehydrated tissue slides were first treated for 30 min with 3% H2O2 to inactivate endogenous peroxidases. After rinsing washing in PBS for 5–10 min, slides were blocked with 10% (w/v) BSA in PBS and then incubated overnight at 4°C with antibodies against Rybp (anti-DEDAF; dilution 1:1000; Chemicon, AB3637; rabbit), Pax2 (dilution 1:200, Babco, PRB276P, rabbit), Pax6 (dilution 1:500, mouse IgG1, DSHB), Nestin (dilution: 1:100, mouse IgG1, DSHB Rat-401), NeuN (dilution: 1:1000, Chemicon MAB377), or TUJ1 (dilution: 1:2000, Sigma T8660). After removing excess antibody, samples were incubated with a 1:400 dilution of biotin-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit (Dako, EO466) or anti-mouse antibodies (Dako, EO433) for 45 minutes at room temperature, washed in PBS, and incubated with avidin-biotinylated enzyme complex for 45 minutes. The reaction was developed with the DAB kit (Vector labs). For better visualization, slides were often slightly counterstained with hematoxylin. Samples were viewed and photographed under epifluorescent illumination with Leica MZFLIII microscope.

Electron microscopy

Dissected P1 and P21 day old eyes were placed in Ito's fixative [68] for 24 h after the cornea had been pierced with a fine needle. The eyes were washed overnight in cacodylate buffer, postfixed with OsO4, dehydrated, and embedded in Epon (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). Semithin sections were stained with toluidine blue. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and viewed with a Zeiss (Oberkochen, Germany) EM 902 electron microscope.

Western blots

Western blotting analysis was conducted upon protein extracts from embryonic stem cells as described earlier [32]. Primary antibodies were used against RYBP (anti-DEDAF; 1:1,000, Chemicon AB3637), GFP (1:1,000, Molecular Probes A11122) and Flag HRP (1:5000, M2, Sigma).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA isolated from the lens and retina of the ROSA26-Rybp/EGFP; αA-crystallin/Cre P1 and P21 day old mice was extracted and reverse transcript was obtained as described elsewhere [16]. Real time PCR was performed as previously described using primers to amplify Pax6, Prox1, MafA, MafB and c-Maf transcripts [69, 70]). The additional primers are: Rybp primers A, (5'-agaccagcgaaacaaaccac-3') and B, (5'-aggaggagcgagtcttttcc-3'); Crystallin βA4 (Cryba4) primers A, (5'-gggtttgttcccagttcct-3') and B, (5'-acctgagtggtgatcgctct-3'); Filensin (Bfsp1) Primers: A, (5'-cattgagattgaaggcagca-3') B, (5'-acactggatccaaggctgag-3'); AP2α primer A, (5'-gtgtcagagatgctgcggta-3') and B (5'-tgaggatggtgtccacgta-3'); Integrin α-6 primers A, (5'-attctcctgagggcttccat-3') and B, (5'-ttgagggaaacaccgtcact-3'); Sox2 primer A, (5'-acttttgtccgagaccgaga-3') and B, (5'-ctccggcaagcgtgtactta-3'); and B2M primers A, (5'-catacgcctgcagagttaagc-3') and B, (5'-gatgcttgatcacatgtctcg-3'). Amplification of the cDNA was performed using 7900 HP Applied Biosystems Real Time PCR machine. Relative fold changes were calculated using CCNI as an internal control as described [70].

Abbreviations

- C:

-

cornea

- Ca:

-

capillary

- CA:

-

cataract

- Co:

-

cortex

- Col:

-

coloboma

- Cre:

-

Cre recombinase

- E:

-

embryonic day

- Ep:

-

corneal epithelium

- GCL:

-

ganglion cell layer

- EGFP:

-

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- H:

-

hyaloid cavity

- HE:

-

hematoxylin and eosin

- INL:

-

inner nuclear layer

- L:

-

lens

- LE:

-

lens epithelium

- M:

-

marginal

- ME:

-

mesenchyme

- NE:

-

neuroepithelium

- NR:

-

neuroretina

- P:

-

postnatal day

- PLF:

-

primary lens fiber cells

- PcG:

-

polycomb group protein

- OC:

-

optic cup

- ON:

-

optic nerve

- ONL:

-

outer nuclear layer

- ORF:

-

open reading frame

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- PM:

-

periocular mesenchyme

- qRT-PCR:

-

quantitative reverse transcriptase – polymerase chain reaction

- S:

-

stroma

- SE:

-

surface ectoderm

- T:

-

transitional zone

- V:

-

ventral

- TG:

-

transgenic

- WT:

-

wild type

References

Marquardt T, Ashery-Padan R, Andrejewski N, Scardigli R, Guillemot F, Gruss P: Pax6 is required for the multipotent state of retinal progenitor cells. Cell. 2001, 105: 43-55. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00295-1.

Donner AL, Maas RL: Conservation and non-conservation of genetic pathways in eye specification. Int J Dev Biol. 2004, 48: 743-53. 10.1387/ijdb.041877ad.

Graw J: The genetic and molecular basis of congenital eye defects. Nat Rev Genet. 2003, 4: 876-88. 10.1038/nrg1202.

Mui SH, Kim JW, Lemke G, Bertuzzi S: Vax genes ventralize the embryonic eye. Genes Dev. 2005, 19: 1249-59. 10.1101/gad.1276605.

Gregory-Evans CY, Williams MJ, Halford S, Gregory-Evans K: Ocular coloboma: a reassessment in the age of molecular neuroscience. J Med Genet. 2004, 41: 881-91. 10.1136/jmg.2004.025494.

Barbieri AM, Lupo G, Bulfone A, Andreazzoli M, Mariani M, Fougerousse F, Consalez GG, Borsani G, Beckmann JS, Barsacchi G, et al: A homeobox gene, vax2, controls the patterning of the eye dorsoventral axis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999, 96: 10729-34. 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10729.

Piatigorsky J: Lens differentiation in vertebrates. A review of cellular and molecular features. Differentiation. 1981, 19: 134-53. 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1981.tb01141.x.

Hejtmancik JF, Kantorow M: Molecular genetics of age-related cataract. Exp Eye Res. 2004, 79: 3-9. 10.1016/j.exer.2004.03.014.

Lupo G, Harris WA, Lewis KE: Mechanisms of ventral patterning in the vertebrate nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006, 7: 103-14. 10.1038/nrn1843.

Bailey TJ, El-Hodiri H, Zhang L, Shah R, Mathers PH, Jamrich M: Regulation of vertebrate eye development by Rx genes. Int J Dev Biol. 2004, 48: 761-70. 10.1387/ijdb.041878tb.

Lang RA: Pathways regulating lens induction in the mouse. Int J Dev Biol. 2004, 48: 783-91. 10.1387/ijdb.041903rl.

Bultman S, Gebuhr T, Yee D, La Mantia C, Nicholson J, Gilliam A, Randazzo F, Metzger D, Chambon P, Crabtree G, et al: A Brg1 null mutation in the mouse reveals functional differences among mammalian SWI/SNF complexes. Mol Cell. 2000, 6: 1287-95. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00127-1.

Stopka T, Skoultchi AI: The ISWI ATPase Snf2h is required for early mouse development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003, 100: 14097-102. 10.1073/pnas.2336105100.

Kamachi Y, Uchikawa M, Collignon J, Lovell-Badge R, Kondoh H: Involvement of Sox1, 2 and 3 in the early and subsequent molecular events of lens induction. Development. 1998, 125: 2521-32.

Gregg RG, Willer GB, Fadool JM, Dowling JE, Link BA: Positional cloning of the young mutation identifies an essential role for the Brahma chromatin remodeling complex in mediating retinal cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003, 100: 6535-40. 10.1073/pnas.0631813100.

Yang Y, Stopka T, Golestaneh N, Wang Y, Wu K, Li A, Chauhan BK, Gao CY, Cveklova K, Duncan MK, et al: Regulation of alphaA-crystallin via Pax6, c-Maf, CREB and a broad domain of lens-specific chromatin. Embo J. 2006, 25: 2107-18. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601114.

Furuta Y, Hogan BL: BMP4 is essential for lens induction in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 1998, 12: 3764-75.

Taranova OV, Magness ST, Fagan BM, Wu Y, Surzenko N, Hutton SR, Pevny LH: SOX2 is a dose-dependent regulator of retinal neural progenitor competence. Genes Dev. 2006, 20: 1187-202. 10.1101/gad.1407906.

West-Mays JA, Zhang J, Nottoli T, Hagopian-Donaldson S, Libby D, Strissel KJ, Williams T: AP-2alpha transcription factor is required for early morphogenesis of the lens vesicle. Dev Biol. 1999, 206: 46-62. 10.1006/dbio.1998.9132.

Dwivedi DJ, Pontoriero GF, Ashery-Padan R, Sullivan S, Williams T, West-Mays JA: Targeted deletion of AP-2alpha leads to disruption in corneal epithelial cell integrity and defects in the corneal stroma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005, 46: 3623-30. 10.1167/iovs.05-0028.

Morgenbesser SD, Williams BO, Jacks T, DePinho RA: p53-dependent apoptosis produced by Rb-deficiency in the developing mouse lens. Nature. 1994, 371: 72-4. 10.1038/371072a0.

McCaffrey J, Yamasaki L, Dyson NJ, Harlow E, Griep AE: Disruption of retinoblastoma protein family function by human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein inhibits lens development in part through E2F-1. Mol Cell Biol. 1999, 19: 6458-68.

Garcia E, Marcos-Gutierrez C, del Mar Lorente M, Moreno JC, Vidal M: RYBP, a new repressor protein that interacts with components of the mammalian Polycomb complex, and with the transcription factor YY1. Embo J. 1999, 18: 3404-18. 10.1093/emboj/18.12.3404.

Buszczak M, Spradling AC: Searching chromatin for stem cell identity. Cell. 2006, 125: 233-6. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.004.

Pirrotta V: Ernst Schering Res Found Workshop. 2006, 97-113.

Bejarano F, Gonzalez I, Vidal M, Busturia A: The Drosophila RYBP gene functions as a Polycomb-dependent transcriptional repressor. Mech Dev. 2005, 122: 1118-29. 10.1016/j.mod.2005.06.001.

Kalenik JL, Chen D, Bradley ME, Chen SJ, Lee TC: Yeast two-hybrid cloning of a novel zinc finger protein that interacts with the multifunctional transcription factor YY1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25: 843-9. 10.1093/nar/25.4.843.

Schlisio S, Halperin T, Vidal M, Nevins JR: Interaction of YY1 with E2Fs, mediated by RYBP, provides a mechanism for specificity of E2F function. Embo J. 2002, 21: 5775-86. 10.1093/emboj/cdf577.

Ogawa H, Ishiguro K, Gaubatz S, Livingston DM, Nakatani Y: A complex with chromatin modifiers that occupies E2F- and Myc-responsive genes in G0 cells. Science. 2002, 296: 1132-6. 10.1126/science.1069861.

Zheng L, Schickling O, Peter ME, Lenardo MJ: The death effector domain-associated factor plays distinct regulatory roles in the nucleus and cytoplasm. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276: 31945-52. 10.1074/jbc.M102799200.

Arrigoni R, Alam SL, Wamstad JA, Bardwell VJ, Sundquist WI, Schreiber-Agus N: The Polycomb-associated protein Rybp is a ubiquitin binding protein. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580: 6233-41. 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.027.

Pirity MK, Locker J, Schreiber-Agus N: Rybp/DEDAF is required for early postimplantation and for central nervous system development. Mol Cell Biol. 2005, 25: 7193-202. 10.1128/MCB.25.16.7193-7202.2005.

Torres M, Gomez-Pardo E, Gruss P: Pax2 contributes to inner ear patterning and optic nerve trajectory. Development. 1996, 122: 3381-91.

Hogan BL, Horsburgh G, Cohen J, Hetherington CM, Fisher G, Lyon MF: Small eyes (Sey): a homozygous lethal mutation on chromosome 2 which affects the differentiation of both lens and nasal placodes in the mouse. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1986, 97: 95-110.

Walther C, Gruss P: Pax-6, a murine paired box gene, is expressed in the developing CNS. Development. 1991, 113: 1435-49.

Grindley JC, Davidson DR, Hill RE: The role of Pax-6 in eye and nasal development. Development. 1995, 121: 1433-42.

Sanyanusin P, McNoe LA, Sullivan MJ, Weaver RG, Eccles MR: Mutation of PAX2 in two siblings with renal-coloboma syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1995, 4: 2183-4. 10.1093/hmg/4.11.2183.

Favor J, Sandulache R, Neuhauser-Klaus A, Pretsch W, Chatterjee B, Senft E, Wurst W, Blanquet V, Grimes P, Sporle R, et al: The mouse Pax2(1Neu) mutation is identical to a human PAX2 mutation in a family with renal-coloboma syndrome and results in developmental defects of the brain, ear, eye, and kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996, 93: 13870-5. 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13870.

Schwarz M, Cecconi F, Bernier G, Andrejewski N, Kammandel B, Wagner M, Gruss P: Spatial specification of mammalian eye territories by reciprocal transcriptional repression of Pax2 and Pax6. Development. 2000, 127: 4325-34.

Livesey FJ, Young TL, Cepko CL: An analysis of the gene expression program of mammalian neural progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004, 101: 1374-9. 10.1073/pnas.0307014101.

Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, William CM, Tanabe Y, Jessell TM, Costantini F: Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev Biol. 2001, 1: 4-10.1186/1471-213X-1-4.

Martinez-Morales JR, Signore M, Acampora D, Simeone A, Bovolenta P: Otx genes are required for tissue specification in the developing eye. Development. 2001, 128: 2019-30.

Baulmann DC, Ohlmann A, Flugel-Koch C, Goswami S, Cvekl A, Tamm ER: Pax6 heterozygous eyes show defects in chamber angle differentiation that are associated with a wide spectrum of other anterior eye segment abnormalities. Mech Dev. 2002, 118: 3-17. 10.1016/S0925-4773(02)00260-5.

Medina-Martinez O, Brownell I, Amaya-Manzanares F, Hu Q, Behringer RR, Jamrich M: Severe defects in proliferation and differentiation of lens cells in Foxe3 null mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2005, 25: 8854-63. 10.1128/MCB.25.20.8854-8863.2005.

Chen Q, Liang D, Yang T, Leone G, Overbeek PA: Distinct capacities of individual E2Fs to induce cell cycle re-entry in postmitotic lens fiber cells of transgenic mice. Dev Neurosci. 2004, 26: 435-45. 10.1159/000082285.

Lovicu FJ, McAvoy JW: Growth factor regulation of lens development. Dev Biol. 2005, 280: 1-14. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.020.

Asahara T, Takahashi T, Masuda H, Kalka C, Chen D, Iwaguro H, Inai Y, Silver M, Isner JM: VEGF contributes to postnatal neovascularization by mobilizing bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells. Embo J. 1999, 18: 3964-72. 10.1093/emboj/18.14.3964.

Kato T, Kure T, Chang JH, Gabison EE, Itoh T, Itohara S, Azar DT: Diminished corneal angiogenesis in gelatinase A-deficient mice. FEBS Lett. 2001, 508: 187-90. 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02897-6.

Berglin L, Sarman S, van der Ploeg I, Steen B, Ming Y, Itohara S, Seregard S, Kvanta A: Reduced choroidal neovascular membrane formation in matrix metalloproteinase-2-deficient mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003, 44: 403-8. 10.1167/iovs.02-0180.

Samolov B, Steen B, Seregard S, van der Ploeg I, Montan P, Kvanta A: Delayed inflammation-associated corneal neovascularization in MMP-2-deficient mice. Exp Eye Res. 2005, 80: 159-66. 10.1016/j.exer.2004.08.023.

Pirrotta V, van Lohuizen M: Differentiation and gene regulation Genomic programs and differentiation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006

Muyrers-Chen I, Hernandez-Munoz I, Lund AH, Valk-Lingbeek ME, van der Stoop P, Boutsma E, Tolhuis B, Bruggeman SW, Taghavi P, Verhoeven E, et al: Emerging roles of Polycomb silencing in X-inactivation and stem cell maintenance. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2004, 69: 319-26. 10.1101/sqb.2004.69.319.

Raaphorst FM: Of mice, flies, and man: the emerging role of polycomb-group genes in human malignant lymphomas. Int J Hematol. 2005, 81: 281-7. 10.1532/IJH97.05023.

Cernilogar FM, Orlando V: Epigenome programming by Polycomb and Trithorax proteins. Biochem Cell Biol. 2005, 83: 322-31. 10.1139/o05-040.

Gil J, Bernard D, Peters G: Role of polycomb group proteins in stem cell self-renewal and cancer. DNA Cell Biol. 2005, 24: 117-25. 10.1089/dna.2005.24.117.

Ringrose L, Paro R: Epigenetic regulation of cellular memory by the Polycomb and Trithorax group proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 2004, 38: 413-43. 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091907.

Levine SS, King IF, Kingston RE: Division of labor in polycomb group repression. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004, 29: 478-85. 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.07.007.

Takihara Y, Tomotsune D, Shirai M, Katoh-Fukui Y, Nishii K, Motaleb MA, Nomura M, Tsuchiya R, Fujita Y, Shibata Y, et al: Targeted disruption of the mouse homologue of the Drosophila polyhomeotic gene leads to altered anteroposterior patterning and neural crest defects. Development. 1997, 124: 3673-82.

Lorente M, Perez C, Sanchez C, Donohoe M, Shi Y, Vidal M: Homeotic transformations of the axial skeleton of YY1 mutant mice and genetic interaction with the Polycomb group gene Ring1/Ring1A. Mech Dev. 2006, 123: 312-20. 10.1016/j.mod.2006.02.003.

Nottoli T, Hagopian-Donaldson S, Zhang J, Perkins A, Williams T: AP-2-null cells disrupt morphogenesis of the eye, face, and limbs in chimeric mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998, 95: 13714-9. 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13714.

Kamachi Y, Uchikawa M, Tanouchi A, Sekido R, Kondoh H: Pax6 and SOX2 form a co-DNA-binding partner complex that regulates initiation of lens development. Genes Dev. 2001, 15: 1272-86. 10.1101/gad.887101.

Wistow GJ, Piatigorsky J: Lens crystallins: the evolution and expression of proteins for a highly specialized tissue. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988, 57: 479-504. 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.002403.

Nagy A, Rossant J, Nagy R, Abramow-Newerly W, Roder JC: Derivation of completely cell culture-derived mice from early-passage embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993, 90: 8424-8. 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8424.

Zhao H, Yang Y, Rizo CM, Overbeek PA, Robinson ML: Insertion of a Pax6 consensus binding site into the alphaA-crystallin promoter acts as a lens epithelial cell enhancer in transgenic mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004, 45: 1930-9. 10.1167/iovs.03-0856.

Soriano P: Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999, 21: 70-1. 10.1038/5007.

Lewandoski M, Meyers EN, Martin GR: Analysis of Fgf8 gene function in vertebrate development. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1997, 62: 159-168.

Chowdhury K, Bonaldo P, Torres M, Stoykova A, Gruss P: Evidence for the stochastic integration of gene trap vectors into the mouse germline. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25: 1531-6. 10.1093/nar/25.8.1531.

Ito SKM: Formaldehyde-glutaraldehyde fixatives containing trinitro compounds. J Cell Biol. 1968, 39: 168A-169A.

Yang Y, Cvekl A: Tissue-specific regulation of the mouse alphaA-crystallin gene in lens via recruitment of Pax6 and c-Maf to its promoter. J Mol Biol. 2005, 351: 453-69. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.05.072.

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD: Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001, 25: 402-8. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. M.L. Robinson (Miami University, Oxford, OH) for the αA-crystallin/cre transgenic mice. We thank the Histopathology Shared Resource of the Albert Einstein Cancer Center for histology, Radma Mahmood and Kveta Cveklova for superb technical assistance. We thank Dr. J.D. Locker for his kind help during revisions of this manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants EY12200 and 14237 (AC) and CA92558 (NSA). A.C. is a recipient of the Irma T. Hirschl Career Scientist Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

M.K.P, N.S.A and A.C. conceived the project, designed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. M.K.P. performed most of the experimental manipulations. W.W. carried out the RT-PCR analyses. L.V.W. contributed to the phenotypic analyses. E.T. performed the E.M. experiments and contributed to the phenotypic analyses. All authors read and modified drafts, and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pirity, M.K., Wang, WL., Wolf, L.V. et al. Rybp, a polycomb complex-associated protein, is required for mouse eye development. BMC Dev Biol 7, 39 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-213X-7-39

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-213X-7-39