Abstract

Background

The bacterial endotoxin, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), is a well-characterized inflammatory factor found in the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria. In this investigation, we studied the cytotoxic interaction between 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulfide (CEES or ClCH2CH2SCH2CH3) and LPS using murine RAW264.7 macrophages. CEES is a sulfur vesicating agent and is an analog of 2,2'-dichlorodiethyl sulfide (sulfur mustard). LPS is a ubiquitous natural agent found in the environment. The ability of LPS and other inflammatory agents (such as TNF-alpha and IL-1beta) to modulate the toxicity of CEES is likely to be an important factor in the design of effective treatments.

Results

RAW 264.7 macrophages stimulated with LPS were found to be more susceptible to the cytotoxic effect of CEES than unstimulated macrophages. Very low levels of LPS (20 ng/ml) dramatically enhanced the toxicity of CEES at concentrations greater than 400 μM. The cytotoxic interaction between LPS and CEES reached a maximum 12 hours after exposure. In addition, we found that tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and interleukin-1-beta (IL-1-beta) as well as phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) also enhanced the cytotoxic effects of CEES but to a lesser extent than LPS.

Conclusion

Our in vitro results suggest the possibility that LPS and inflammatory cytokines could enhance the toxicity of sulfur mustard. Since LPS is a ubiquitous agent in the natural environment, its presence is likely to be an important variable influencing the cytotoxicity of sulfur mustard toxicity. We have initiated further experiments to determine the molecular mechanism whereby the inflammatory process influences sulfur mustard cytotoxicity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In this investigation, we explored the potential cytotoxic interaction between LPS and CEES using a murine macrophage cell line (RAW264.7). CEES is a monofunctional analog of sulfur mustard (bis-2-(chloroethyl)sulfide) which a bifunctional vesicant and a chemical warfare agent. Both bis-2-(chloroethyl)sulfide) and CEES are known to provoke acute inflammatory responses in skin [1–3]. The resulting skin blistering is thought to involve the stimulation of specific protease(s) [4]. Apoptosis is now considered a possible molecular mechanism whereby CEES induces cytotoxicity [5, 6].

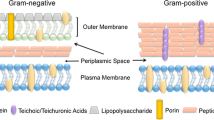

LPS is a major component of the cell wall of gram-negative bacteria and is known to trigger a variety of inflammatory reactions in macrophages and other cells having CD14 receptors [7, 8]. In particular, LPS is known to stimulate the macrophage secretion of nitric oxide [9] and inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and interleukin-1-beta (IL-1-beta) [10]. For this reason, we also determined if TNF-alpha or IL-1-beta were capable of enhancing the cytotoxic effects of CEES.

LPS stimulation of macrophages is known to involve the activation of protein phosphorylation by kinases as well as the activation of nuclear transcription factors such as NF-kappaB [10–13]. The activation of protein kinase C (PKC) by diacylglycerol is also a key event in LPS macrophage activation [8]. In vitro experiments have shown that the secretion of TNF-alpha and IL-1-beta by LPS-stimulated monocytes is dependent upon PKC activation [13, 14]. In this study, we also determined if phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) activation of PKC also enhanced CEES toxicity. Evidence suggests that LPS [15, 16] as well as TNF-alpha [17] stimulate the production of free radicals by macrophages. Our long-term goal is to understand the molecular mechanism of sulfur mustard toxicity and to determine if free radical production plays an important role in this toxicity.

In our experiments, cytotoxicity was measured by a decrease in the optical density by the MTT ((3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay or by an increase in the fluorescence of propidium iodide (PI). The MTT assay is based on reduction of MTT by actively growing cells to produce a blue formazan product with absorbance at 575 nm. A low MTT absorbance indicates cell death. The PI assay differentiates between live and dead cells. Cells that have lost membrane integrity cannot exclude PI, which emits a red fluorescence after binding to cellular DNA or double stranded RNA. A high PI% indicates cell death.

Results

Cytotoxic interaction between LPS and CEES as measured by the MTT assay

RAW 264.7 macrophages were incubated with LPS (100 ng/ml), CEES (500 μM) or both agents for 24 hours and cell viability then measured by the MTT assay. As shown in Figure 1, we found that LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages were markedly more susceptible (p < 0.05) to CEES toxicity (24 hr) than resting macrophages as indicated by the dramatic drop in dehydrogenase activity. In the absence of LPS, CEES at a level of 500 μM did not significantly affect cell viability as measured by the MTT assay.

The characteristics of CEES toxicity to LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages were further characterized by varying the concentrations of both LPS and CEES. The MTT data in Figure 2 show that very low levels (25 ng/ml) of LPS dramatically enhanced the toxicity of CEES (measured after 24 hr) to macrophages at concentrations > 300 μM. In general, LPS levels beyond 25 ng/ml did not further enhance the toxicity of CEES. However, LPS level at a level of 100 ng/ml significantly increased the cytotoxicity of 300 μM CEES compared to LPS activated RAW265.7 cells not treated with CEES. Statistical analyses indicate that cells treated with 100 μM CEES were not significantly different from control cells (not treated with CEES) in the presence of 0, 25 or 50 ng/ml of LPS. However, at a LPS level of 100 ng/ml, cells treated with 100 μM CEES showed a great MTT optical density than control cells. This might be due to a slight mitogenic response to low levels of CEES.

Time course for the cytotoxic interaction between LPS and CEES as measured by the propidium iodide (PI) assay

In order to insure that our results could be reproduced with an alternative assay for cell viability, we also utilized the propidium iodide (PI) assay. In this assay, the percent fluorescence increase over the control cells (i.e., 100 × (PItreatment-PIcontrol)/PIcontrol) indicates cytotoxicity. For each experiment, the value for the control cells is zero and is not, therefore, shown. Figure 3 indicates that the PI assay provides the same qualitative results as the MTT assay, i.e., a synergistic toxic interaction between CEES (500 μM) and LPS (20 ng/ml). Moreover, the cytotoxic interaction between LPS and CEES was noticeable after 6 hours (p < 0.05) and reached a maximum 12 hours after exposure. After 24 hours, CEES (500 μM) was significantly toxic to RAW 264.7 macrophages even in the absence of LPS. LPS alone was never significantly different than cells with no treatment, which always has a zero percent PI% increase.

TNF-alpha and IL-1beta also enhance the cytotoxic effect of CEES

LPS from Gram-negative bacteria binds to CD14 and initiates a complex signal transduction pathway involving the Toll receptor family, which eventually results in the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha and IL-1beta. We, therefore, investigated the potential roles of TNF-alpha and IL-1beta in enhancing CEES cytotoxicity. Table 1 shows that IL-1beta (50 ng/ml) and CEES (500 μM) are significantly more cytotoxic (after 24 hours) when administered together than when administered alone. In this experiment, LPS (25 ng/ml) and CEES (500 μM) combined gave PI(%) and MTT values of 120.8 ± 2.3 and 0.25 ± 0.07, respectively. These MTT data suggest that LPS, at 25 ng/ml, is able to enhance the toxicity of CEES (an MTT value of 0.25 ± 0.07) to a greater extent (p < 0.05) than IL-1beta at 50 ng/ml (an MTT value of 0.74 ± 0.07). The ternary mixture of LPS (25 ng/ml), IL-1beta (50 ng/ml) and CEES (500 μM) was not found to be more cytotoxic than LPS (25 ng/ml) and CEES (500 μM).

Table 2 shows completely analogous data with TNF-alpha, i.e., an amplification of CEES toxicity (after 24 hours) in the presence of the inflammatory cytokine. In this experiment, LPS at 25 ng/ml plus CEES (at 500 μM) gave PI(%) and MTT values of 62.6 ± 1.4 and 0.32 ± 0.05, respectively. This indicates that TNF-alpha at 50 ng/ml is not as potent at LPS (at 25 ng/ml) in enhancing the cytotoxicity of CEES at 500 μM. TNF-alpha combined with LPS (in the absence of CEES) was found to not exert any cytotoxic effect on the RAW264.7 macrophages.

Protein kinase C is a non-receptor serine/threonine kinase that is maximally active in the presence of diacylglycerol and calcium ions. In vitro experiments by Coffey et al.[14] have shown that TNF-alpha and IL-1beta secretion and mRNA accumulation by monocytes following LPS treatment is dependent on PKC activity. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) is a specific activator of group A and group B protein kinase C. We wanted to determine, therefore, if protein kinase C activation by PMA would enhance the toxicity of CEES. As shown in Table 3, the combination of PMA (50 ng/ml) and CEES (500 μM) was more cytotoxic (after 24 hours) toward the RAW264.7 macrophages than LPS or CEES alone. However, as was the case with IL-1beta and TNF-alpha, PMA was not as effective as LPS in enhancing CEES toxicity.

Discussion

We have found that inflammatory agents such as LPS, TNF-alpha, IL-1beta, and PMA amplify the cytotoxicity of CEES to RAW264.7 macrophages. There is evidence suggesting that CEES can modulate levels of inflammatory cytokines but this information is controversial and inconsistent. Cultured monocytes exposed to CEES show a transient increase in TNF-alpha [18]. Similarly, cultured normal human keratinocytes exposed to CEES show a transient increase in both TNF-alpha and IL-1beta [19, 20]. In contrast to the results of Arroyo et al. [18–20], Ricketts et al. [21] found that IL-1beta or TNF-alpha protein did not increase in sulfur mustard-exposed mouse skin. Blaha et al. [1], using an in vitro human skin model, found that CEES treatment resulted in a decreased level of IL-1alpha.

Sabourin et al. [3] also addressed this issue and studied the in vivo temporal sequence of inflammatory cytokine gene expression in sulfur mustard exposed mouse skin. These investigators found an increase in IL-1beta mRNA levels after 3 hours that dramatically increased between 6–24 hours post exposure [3]. Moreover, immunohistochemical studies showed an increase in tissue levels of IL-1beta [3]. The in vitro results reported here support a role for inflammatory cytokines in the mechanism and kinetics of CEES toxicity. Our unique findings with regards to LPS are significant because they demonstrate that this bacterial endotoxin enhances CEES toxicity even when present at extremely low levels, i.e., nanograms of LPS per ml.

LPS is ubiquitous and is present in serum, tap water, and dust. Military and civilian personnel would, indeed, always have some degree of exposure to environmental LPS, which could increase the toxicity of sulfur mustard. In addition, there is always the possibility of purposeful LPS exposure. Our primary future goals are to understand the general mechanism for the enhanced toxicity of CEES in the presence of inflammatory agents and use this information to develop effective countermeasures. Our experiments with PMA (Table 3) suggest that the activation of protein kinase C may play a key role in molecular mechanism whereby LPS enhances the cytotoxic of CEES.

In experiments that will be reported elsewhere, we have found the antioxidants such as RRR-alpha-tocopherol and N-acetylcysteine are effective in reducing the cytotoxic effects of CEES on LPS-stimulated macrophages. We have also initiated experiments to distinguish the roles of apoptosis and necrosis in the observation reported here.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that that LPS dramatically enhances the toxicity of sulfur mustard. Since LPS is a ubiquitous agent in the natural environment, its presence is likely to be an important variable influencing the cytotoxicity of sulfur mustard toxicity. LPS is known to stimulate the production of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha and IL-1beta in human monocytes [10]. We, therefore, also determined if these cytokines influenced the cytotoxicity of CEES. The data in Tables 1 and 2 demonstrate that both these cytokines enhance the cytotoxicity of CEES as measured by either the MTT assay or the PI assay. Inhibition of protein kinase C is known to block the secretion of TNF-alpha and IL-1beta [10] whereas stimulation of protein kinase C promotes TNF-alpha and IL-1beta production [22]. The data reported in Table 3 show that stimulation of protein kinase C activity by PMA also enhances the cytotoxicity of CEES. Collectively, the data reported here provide the basis for future experiments attempting to determine the signal transduction mechanisms whereby inflammatory agents enhance sulfur mustard cytotoxicity.

Methods

Materials

LPS (Escherichia Coli Serotype 0111:B4) and PMA (Phorbol 12-Myristate 13-Acetate) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. St. Louis, MO. Murine IL-1-beta was obtained from Research Diagnostic Inc. (Flanders, NJ). r-TNF-alpha (human) was obtained from Promega Co (Madison, WI).

Cell culture and treatments

RAW264.7 murine macrophage-like cells (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) were cultured at 37°C in a humidified incubator (95% air with 5% CO2) in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (GiBcoBRL Grand Island, NY). Adherent cells were subcultured over night in 96 well Costar tissue culture plates in serum-free RPMI with 0.1% BSA (RPMI-0.1%BSA).

MTT assay for determination of cell viability

This assay for cell viability is based on the reduction of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) by mitochondrial dehydrogenase in viable cells to produce a purple formazan product. Schweitzer et al. [23] have shown that this assay provides linearity between optical density and cell number. This assay was performed by a slight modification of the method described by Wasserman et al. [24, 25]. Briefly, at the end of each experiment, cells cultured in 96 well plates (with 100 μl of medium per well) were incubated with MTT (20 μl of 5 μg/ml per well) at 37°C for 4 hours. The formazan product was solubilized by addition of 100 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 100 μl of 10% SDS (in 0.01 M HCl) for 16 hours at 37°C. The dehydrogenase activity was expressed as the absorbance (read with a Molecular Devices microplate reader) of the formazan product at 575 nm.

Dye exclusion assay (PI assay)

This assay uses propidium iodide (PI) dye to differentiate live and dead cell [26–28]. Cells that have lost membrane integrity cannot exclude PI, which emits a red fluorescence after binding to cellular DNA or double stranded RNA. After each experiment, cells were washed with PBS and incubated with 200 μl of RPMI medium with 5 μg/ml PI for five minutes at room temperature. PI fluorescence was measured using a Fluostar Galaxy microplate reader using an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 650 nm. We expressed the results as the percent increase in the fluorescence of treated cells over the fluorescence of control cells (no treatments), i.e., 100 × (PItreatment-PIcontrol)/PIcontrol)

Statistical analyses

Means among treatments were compared by one-way ANOVA followed by the Scheffe test with a significance level of 0.05. In both the Tables and Figures, means not sharing a common letter are significantly different (p < 0.05). Means sharing a common letter are not significantly different. The means and standard deviations of three independent experiments are provided in both the Figures and Tables.

References

Blaha M, Bowers W, Kohl J, DuBose D, Walker J: Il-1-related cytokine responses of nonimmune skin cells subjected to CEES exposure with and without potential vesicant antagonists. In Vitr Mol Toxicol. 2000, 13: 99-111. 10.1089/109793300440695.

Blaha M, Bowers W, Kohl J, DuBose D, Walker J, Alkhyyat A, Wong G: Effects of CEES on inflammatory mediators, heat shock protein 70A, histology and ultrastructure in two skin models. J Appl Toxicol. 2000, 20 (Suppl 1): S101-8. 10.1002/1099-1263(200012)20:1+<::AID-JAT672>3.0.CO;2-R.

Sabourin CL, Petrali JP, Casillas RP: Alterations in inflammatory cytokine gene expression in sulfur mustard-exposed mouse skin. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2000, 14: 291-302. 10.1002/1099-0461(2000)14:6<291::AID-JBT1>3.0.CO;2-B.

Ray P, Chakrabarti AK, Broomfield CA, Ray R: Sulfur mustard-stimulated protease: a target for antivesicant drugs. J Appl Toxicol. 2002, 22: 139-40. 10.1002/jat.829.

Hur GH, Kim YB, Choi DS, Kim JH, Shin S: Apoptosis as a mechanism of 2-chloroethylethyl sulfide-induced cytotoxicity. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 1998, 110: 57-70. 10.1016/S0009-2797(97)00112-9.

Zhang P, Ng P, Caridha D, Leach RA, Asher LV, Novak MJ, Smith WJ, Zeichner SL, Chiang PK: Gene expressions in Jurkat cells poisoned by a sulphur mustard vesicant and the induction of apoptosis. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2002, 137: 245-52. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704856.

Wright SD, Ramos RA, Tobias PS, Ulevitch RJ, Mathison JC: CD14, a receptor for complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. Science. 1990, 249: 1431-3.

Downey JS, Han J: Cellular activation mechanisms in septic shock. Front Biosci. 1998, 3: d468-76.

Tepperman BL, Chang Q, Soper BD: Protein kinase C mediates lipopolysaccharide- and phorbol-induced nitric-oxide synthase activity and cellular injury in the rat colon. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2000, 295: 1249-57.

Shapira L, Takashiba S, Champagne C, Amar S, Van Dyke TE: Involvement of protein kinase C and protein tyrosine kinase in lipopolysaccharide-induced TNF-alpha and IL-1 beta production by human monocytes. J Immunol. 1994, 153: 1818-24.

Chen CC, Wang JK, Lin SB: Antisense oligonucleotides targeting protein kinase C-alpha, -beta I, or -delta but not -eta inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide synthase expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages: involvement of a nuclear factor kappa B-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 1998, 161: 6206-14.

Fujihara M, Connolly N, Ito N, Suzuki T: Properties of protein kinase C isoforms (beta II, epsilon, and zeta) in a macrophage cell line (J774) and their roles in LPS-induced nitric oxide production. J Immunol. 1994, 152: 1898-906.

Shapira L, Sylvia VL, Halabi A, Soskolne WA, Van Dyke TE, Dean DD, Boyan BD, Schwartz Z: Bacterial lipopolysaccharide induces early and late activation of protein kinase C in inflammatory macrophages by selective activation of PKC-epsilon. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997, 240: 629-34. 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7717.

Coffey RG, Weakland LL, Alberts VA: Paradoxical stimulation and inhibition by protein kinase C modulating agents of lipopolysaccharide evoked production of tumour necrosis factor in human monocytes. Immunology. 1992, 76: 48-54.

Fu Y, McCormick CC, Roneker C, Lei XG: Lipopolysaccharide and interferon-gamma-induced nitric oxide production and protein oxidation in mouse peritoneal macrophages are affected by glutathione peroxidase-1 gene knockout. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 2001, 31: 450-9. 10.1016/S0891-5849(01)00607-4.

deRojas_Walker T, Tamir S, Ji H, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR: Nitric oxide induces oxidative damage in addition to deamination in macrophage DNA. Chem Res in Toxicol. 8: 473-477.

Wang S, Leonard SS, Castranova V, Vallyathan V, Shi X: The role of superoxide radical in TNF-alpha induced NF-kappaB activation. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1999, 29: 192-9.

Arroyo CM, Von Tersch RL, Broomfield CA: Activation of alpha-human tumour necrosis factor (TNF-alpha) by human monocytes (THP-1) exposed to 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulphide (H-MG). Human and Experimental Toxicology. 1995, 14: 547-53.

Arroyo CM, Schafer RJ, Kurt EM, Broomfield CA, Carmichael AJ: Response of normal human keratinocytes to sulfur mustard: cytokine release. Journal of Applied Toxicology : Jat. 2000, 20 (Suppl 1): S63-72. 10.1002/1099-1263(200012)20:1+<::AID-JAT687>3.0.CO;2-B.

Arroyo CM, Schafer RJ, Kurt EM, Broomfield CA, Carmichael AJ: Response of normal human keratinocytes to sulfur mustard (HD): cytokine release using a non-enzymatic detachment procedure. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1999, 18: 1-11. 10.1191/096032799678839329.

Ricketts KM, Santai CT, France JA, Graziosi AM, Doyel TD, Gazaway MY, Casillas RP: Inflammatory cytokine response in sulfur mustard-exposed mouse skin. J Appl Toxicol. 2000, 20 (Suppl 1): S73-6. 10.1002/1099-1263(200012)20:1+<::AID-JAT685>3.0.CO;2-H.

Kontny E, Ziokowska M, Ryzewska A, Maliski W: Protein kinase c-dependent pathway is critical for the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-alpha, IL-1beta, IL-6). Cytokine. 1999, 11: 839-48. 10.1006/cyto.1998.0496.

Schweitzer CM, van de Loosdrecht AA, Jonkhoff AR, Ossenkoppele GJ, Huijgens PC, Drager AM, Broekhoven MG, Langenhuijsen MM: Spectrophotometric determination of clonogenic capacity of leukemic cells in a semisolid microtiter culture system. Exp Hematol. 1993, 21: 573-8.

Wasserman TH, Twentyman P: Use of a colorimetric microtiter (MTT) assay in determining the radiosensitivity of cells from murine solid tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1988, 15: 699-702.

Twentyman PR, Luscombe M: A study of some variables in a tetrazolium dye (MTT) based assay for cell growth and chemosensitivity. Br J Cancer. 1987, 56: 279-85.

Dengler WA, Schulte J, Berger DP, Mertelsmann R, Fiebig HH: Development of a propidium iodide fluorescence assay for proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. Anticancer Drugs. 1995, 6: 522-32.

Sano N, Kurata O, Okamoto N, Ikeda Y: A new fluorochromasia method using a fluorescence microplate reader for assay of cytotoxic activity of carp leucocytes. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1995, 47: 173-8. 10.1016/0165-2427(94)05378-6.

Zhang L, Mizumoto K, Sato N, Ogawa T, Kusumoto M, Niiyama H, Tanaka M: Quantitative determination of apoptotic death in cultured human pancreatic cancer cells by propidium iodide and digitonin. Cancer Lett. 1999, 142: 129-37. 10.1016/S0304-3835(99)00107-X.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a United States Army Medical Research Command Grant: The Influence of Antioxidant Liposomes on Macrophages Treated with Mustard Gas Analogues, USAMRMC Grant No. 98164001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

WLS drafted the manuscript and supervised the overall conduct of the research, which was performed in his laboratory. MQ carried out all of the experimental work in this study and performed the statistical analyses. MS (along with WLS) conceived of the study, participated in the study design, and provided continuous evaluation of the experimental data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Stone, W.L., Qui, M. & Smith, M. Lipopolysaccharide enhances the cytotoxicity of 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulfide. BMC Cell Biol 4, 1 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2121-4-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2121-4-1