Abstract

Background

The mitotic exit network (MEN) is required for events at the end of mitosis such as degradation of mitotic cyclins and cytokinesis. Bub2 and its binding partner Bfa1 act as a GTPase activating protein (GAP) to negatively regulate the MEN GTPase Tem1. The Bub2/Bfa1 checkpoint pathway is required to delay the cell cycle in response to mispositioned spindles. In addition to its role in mitotic exit, Tem1 is required for actomyosin ring contraction.

Results

To test the hypothesis that the Bub2 pathway prevents premature actin ring assembly, we compared the timing of actin ring formation in wild type, bub2Δ, mad2Δ, and bub2Δmad2Δ cells both with and without microtubules. There was no difference in the timing of actin ring formation between wild type and mutant cells in a synchronized cell cycle. In the presence of nocodazole, both bub2Δ and mad2Δ cells formed rings after a delay of the same duration. Double mutant bub2Δmad2Δ and bfa1Δmad2Δ cells formed rings at the same time with and without nocodazole. To determine if Bub2 has an effect on actomyosin ring contraction through its regulation of Tem1, we used live cell imaging of Myo1-GFP in a bub2Δ strain. We found a significant decrease in the total time of contraction and an increase in rate of contraction compared to wild type cells. We also examined myosin contraction using Myo1-GFP in cells overexpressing an epitope tagged Bub2. Surprisingly, overexpression of Bub2 also led to a significant increase in the rate of contraction, as well as morphological defects. The chained cell phenotype caused by Bub2 overexpression could be rescued by co-overexpression of Tem1, and was not rescued by deletion of BFA1.

Conclusion

Our data indicate that the Bub2 checkpoint pathway does not have a specific role in delaying actin ring formation. The observed increase in the rate of myosin contraction in the bub2Δ strain provides evidence that the MEN regulates actomyosin ring contraction. Our data suggest that the overexpression of the Bub2 fusion protein acts as a dominant negative, leading to septation defects by a mechanism that is Tem1-dependent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The coordination of multiple events during M phase is essential for accurate chromosome segregation. Mitotic checkpoints ensure that chromosomes and the spindle are correctly aligned, and mitotic kinase activity prevents cytokinesis from occurring before mitosis is completed. Budding yeast is an excellent model system to study the complex regulation that couples mitotic exit with the onset of actomyosin ring contraction to complete cell division.

The mitotic checkpoint in budding yeast has two separate pathways, one for sensing kinetochore attachment to microtubules, and another for sensing spindle position [1]. The first pathway requires a number of known genes, including MAD2, and acts to prevent the metaphase to anaphase transition [2]. The second pathway relies on the Bub2/Bfa1 complex to inhibit mitotic exit [3–6]. Both pathways must be intact for complete arrest of the cell cycle in mitosis in response to microtubule depolymerization, as deletion of genes in a single pathway results in a cell cycle delay after which cells exit mitosis [3–6].

The spindle orientation pathway inhibits exit from mitosis through negative regulation of the mitotic exit network (MEN) [4]. Tem1, a small GTPase at the top of the pathway, is activated by its GEF Lte1, and inactivated by the two part GAP Bub2/Bfa1 [7–9]. The MEN regulates both mitotic exit and the onset of cytokinesis and septation. MEN activation leads to mitotic cyclin degradation, and the inactivation of mitotic kinase activity is required for cytokinesis [10, 11]. In addition, some MEN proteins localize to the bud neck at the time of cytokinesis, and Tem1 has been shown to be required for myosin contraction [12–16]. Examination of actin ring formation in apc2–8 mutants with and without a BUB2 deletion led to the hypothesis that the Bub2 pathway acts to prevent premature actin ring formation [17, 18]. This model predicts that bub2Δ cells will form actin rings earlier than BUB2 cells under conditions where the Bub2 checkpoint pathway is normally activated. It has also been proposed that Bub2 acts every cell cycle to restrain Tem1 activity until the end of mitosis [18], in which case even unperturbed cells lacking Bub2 may show premature actin ring formation. Here, we test these hypotheses by examining actin ring formation in synchronized cells with and without nocodazole to depolymerize microtubules and cause checkpoint activation. We found no evidence that the Bub2 checkpoint pathway acts to prevent premature actin ring formation, but we did see an effect on myosin contraction in bub2Δ cells, as well as a septation defect in cells overexpressing a dominant negative Bub2.

Results

The Bub2 checkpoint pathway does not regulate actin ring formation

Previous studies showed that deletion of BUB2 led to MEN dependent actin ring formation in an apc2–8 mutant at the non-permissive temperature [17, 18]. This led to the hypothesis that the Bub2 branch of the spindle assembly checkpoint specifically prevents premature actin ring formation. To test this idea, we looked at the timing of actin ring assembly in synchronized cells. Wild-type, bub2Δ, mad2Δ, and bub2Δmad2Δ cells were arrested in G1 using α-mating factor. After release from the arrest, cells were fixed at 10-minute intervals as they progressed through the cell cycle and stained for actin filaments. As shown in Figure 1A, actin ring formation peaked 80 minutes after release from G1 arrest in all strains. Therefore, deletion of BUB2 did not noticeably affect the timing of actin ring formation in a normal cell cycle.

The Bub2 checkpoint pathway does not regulate actin ring formation. A. and B. Actin ring formation in synchronized cells. Isogenic wild type (KSY3), bub2Δ (KSY19), bub2Δmad2Δ (KSY47), mad2Δ (KSY51), bub2Δbfa1Δ (KSY110) and mad2Δbfa1Δ (KSY111) strains were arrested in G1 with α mating factor, released from arrest and fixed at regular intervals during mitosis. Cells were stained for actin with Alexa 586 phalloidin and ≥ 300 cells were examined microscopically at each time point to calculate the percentage of cells with an actin ring. Reproducible results were obtained in three independent experiments, and representative results from a single experiment are shown. C. and D. Actin ring formation in nocodazole. The same strains as in A. and B. were treated as above, except for the addition of nocodazole at release from α mating factor (time 0).

We next examined actin ring formation after perturbation of the cell cycle using nocodazole, a drug that causes microtubule disassembly. As before, wild-type, bub2Δ, mad2Δ, and bub2Δmad2Δ cells were arrested in G1 using α-mating factor. Cells were released from the arrest into media containing 15 μg/ml nocodazole, fixed at 10-minute intervals, and stained for actin filaments. As expected, wild type cells did not form an actin ring due to cell cycle arrest (Figure 1C). Cells lacking either BUB2 or MAD2 formed actin rings with the same kinetics, with actin rings peaking at 140 minutes after release from G1 arrest (Figure 1C). The delay in actin ring formation in these strains relative to untreated cells is consistent with the cell cycle delay caused by loss of one of the two spindle damage checkpoints [3–6]. Double mutant bub2Δmad2Δ cells had peak actin ring formation at 80 minutes (Figure 1C), the same as unperturbed cells (Figure 1A), consistent with the complete loss of mitotic spindle checkpoints in the double mutant.

Our data show that actin ring formation in the presence of nocodazole occurs at the same time in bub2Δ cells as mad2Δ cells. Additionally, bub2Δmad2Δ cells form rings at the same time with or without microtubules. Therefore, Bub2 does not specifically restrain actin ring formation in response to spindle damage.

Bfa1 does not show a Bub2 independent effect on actin ring formation

It has been proposed that Bfa1 has Bub2 independent functions, as overexpression of Bfa1 causes mitotic arrest even in the absence of Bub2 [6, 19]. Therefore, we analyzed actin ring formation in synchronized bub2Δbfa1Δ and mad2Δbfa1Δ cells with and without nocodazole to see if deletion of BFA1 had an additional effect. In unperturbed cells, actin ring formation peaked at 80 minutes in wild type controls as well as bub2Δbfa1Δ and mad2Δbfa1Δ cells, the same as in bub2Δ and mad2Δ cells (Figure 1A and 1B). In nocodazole, bub2Δbfa1Δ cells had a peak of actin ring formation at 140 minutes, the same as in bub2Δ cells (Figure 1C and 1D). Nocodazole treated mad2Δbfa1Δ cells had a peak of actin ring formation at 80 minutes, similar to mad2Δbub2Δ cells in nocodazole and untreated cells (Figure 1C and 1D). Therefore, we found no evidence for Bfa1 having a Bub2 independent effect on actin ring formation.

The rate of myosin contraction is affected by Bub2

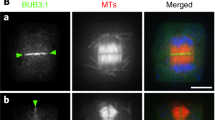

Previous studies have suggested that the MEN regulates actomyosin ring contraction [14]. To test this hypothesis, we examined myosin contraction using Myo1-GFP in bub2Δ cells and compared myosin dynamics in bub2Δ cells to wild type and mad2Δ. Cells expressing Myo1-GFP were filmed at one-minute intervals on agarose pads and analyzed as described in Methods. Cells had a band of Myo1-GFP fluorescence across the bud neck that began to decrease in size at the onset of cytokinesis (Figure 2). The total time of contraction was measured from the time when the Myo1-GFP band began to decrease in size until Myo1-GFP was no longer visible at the bud neck (Figure 2 and Table 1). For wild type cells, the time of contraction was an average of 8.1 min (+/- 0.9), consistent with previously published results (Table 1, Figure 2A, and Additional File 1) [20, 21]. Deletion of BUB2 resulted in a more rapid contraction, 5.9 min (+/- 1.3), (P < .005, Table 1, Figure 2B, and Additional File 2). In contrast, deletion of MAD2 resulted in a slightly slower average time of Myo1-GFP contraction, 10.1 min (+/- 3.5), although this difference was not significantly different from wild type (Table 1). We also calculated the average rate of contraction by measuring the width of the bud neck and dividing by the time of contraction. Deletion of BUB2 resulted in a significantly increased rate, 0.23 μm/min, compared to 0.16 μm/min in wild type cells (Table 1). The rapid contraction of the Myo1-GFP ring in bub2Δ cells prevented the observation of a clear "dot" of myosin signal normally seen at the bud neck at the end of cytokinesis (Figure 2). Analysis of fluorescence intensity profiles indicated that the Myo1-GFP signal ingressed equally from both sides without a loss of intensity. Overall, this data shows that the Bub2 checkpoint pathway has an effect on the timing of actomyosin ring contraction, while the Mad2 branch of the pathway does not.

Deletion of Bub2 decreases the time of myosin contraction. A. Wild type cells expressing Myo1-GFP (KSY70) show contraction of myosin over 10 minutes. B. bub2Δ cells expressing Myo1-GFP (KSY71) show contraction of myosin over 4 minutes. The asterisk indicates the frame (T = 0) after which contraction is evident. Images in the series were taken at one-minute intervals.

Bub2 overexpression affects myosin contraction and causes septation defects

Since bub2Δ caused an increase in the rate of contraction, we wanted to determine if overexpression of Bub2 would slow contraction. Bub2 tagged at the N terminus with T7 and at the C terminus with 6His under control of the inducible GAL1 promoter [19] was integrated into wild type cells expressing Myo1-GFP. These cells were grown in YPR, and then arrested in G1 with α factor with the addition of galactose for three hours to induce Bub2 expression. After release from G1 arrest, Myo1-GFP images were captured as cells underwent cytokinesis. Unexpectedly, Bub2 overexpression increased the speed and rate of Myo1 contraction similar to bub2Δ (Table 1). This result could be due to the overexpressed Bub2, which is tagged with T7 and 6His, acting as a dominant negative. See Additional file 3 for a time-lapse image of Myo1-GFP following Bub2 overexpression.

We further investigated the effects of T7-Bub2-6His overexpression by comparing cells with the GAL1-T7-Bub2-6His construct grown in conditions to repress (YPD) or induce (YPGR) expression. All strains showed a similar level of Bub2 protein expression when grown in YPGR (Figure 3C). As shown previously, cells exhibited slower growth on YPGR plates compared to YPD [19]. The slow growth was evident even in bub2Δ and bfa1Δ backgrounds (Figure 3A and 3B). This growth defect was rescued by co-overexpression of Tem1 using the GAL1 promoter (Figure 3A, B, and 3D). These data support the idea that the T7-Bub2-6His acts as a dominant negative.

Overexpression of a Bub2 construct slows growth. A. Cells grown on YPD at 30°C for two days. B. Cells grown on YPGR at 30°C for two days. 1.) wild type (KSY3), 2.) wild type with GAL1-BUB2 (KSY129), 3.) bub2Δ with GAL1-BUB2 (KSY130), 4.) bfa1Δ with GAL1-BUB2 (KSY169) 5.) wild type with GAL1-Tem1 and GAL1-Bub2 (KSY171). C. GAL1-T7-Bub2-6His is expressed in galactose and repressed in glucose. Anti-T7 blot of protein extracts lane 1: wild type with GAL1-BUB2 (KSY129) grown in YPD, lane 2: wild type with GAL1-BUB2 (KSY129) grown in YPGR, lane 3: bub2Δ with GAL1-BUB2 (KSY130) grown in YPD, lane 4: bub2Δ with GAL1-BUB2 (KSY130) grown in YPGR, lane 5: bfa1Δ with GAL1-BUB2 (KSY169) grown in YPD, lane 6: bfa1Δ with GAL1-BUB2 (KSY169) grown in YPGR. D. Expression of GAL1-TEM induced by galactose and repressed by glucose. Anti-myc blot of protein extracts lane 1: GAL1-Tem1 GAL1-Bub2 (KSY171) in YPD, lane 2: GAL1-Tem1 GAL1-Bub2 (KSY171) in YPGR.

The overexpression of this Bub2 construct has been reported to cause a cytokinesis defect, although the data was not shown [19]. To study this effect more closely, we determined effects on cell morphology by examining cells grown in YPD or YPGR with and without zymolase treatment to remove the cell wall. In a wild type background, cells with the GAL1-T7-Bub2-6His construct grown on YPD had a very low incidence of the chain phenotype, defined as three or more cell bodies (Figure 4). After induction of Bub2 overexpression, an average of 53% of cells exhibited the chained phenotype (Figure 4). After treatment with zymolase, the chains were reduced to 42% on average (Figure 4). In support of the idea that GAL1-T7-Bub2-6His acts in a dominant negative fashion, the effect of overexpression was similar in a bub2Δ strain, with 55.5% of bub2Δ cells exhibiting a chain phenotype before zymolase, and 43% after zymolase treatment (Figure 4). If the epitope-tagged Bub2 were acting the same as endogenous Bub2, one would expect the phenotype to be relieved, rather than exacerbated, by deletion of BUB2. This data also shows that deletion of BUB2 does not cause a cytokinesis or septation defect, as wild type cells and bub2Δ cells had similar numbers of chained cells on YPD (Figure 4). Unlike the previous report [19], we did not find that deletion of BFA1 rescued the chain phenotype (Figure 4). The morphological defects were rescued by co-overexpression of Tem1, which reduced the percentage of chained cells in YPGR to similar levels as in YPD (Figure 4). Together, our data shows that overexpression of a T7-Bub2-6His fusion protein acts as a dominant negative, causing a chained cell phenotype that can be rescued by Tem1 overexpression. The results of the zymolase assay suggest that overexpression of Bub2 caused both a cytokinesis and a septation defect.

Bub2 overexpression causes cytokinesis and septation defects that are rescued by co-overexpression of Tem1. Cells were grown overnight (15 hours) in YPD or YPGR, then fixed. Strains used were: GAL1-BUB2 (KSY 129), GAL1-BUB2 bub2Δ (KSY130), GAL1-BUB2 bfa1Δ (KSY169), and GAL1-Bub2 GAL1-Tem1 (KSY171). Cells with (+ zym) and without zymolase treatment were examined under a microscope and the percentage of cells with chains (3 or more cell bodies) was calculated. Results shown are an average of three independent experiments, and error bars represent the standard deviation. 200 cells were counted for each treatment.

Because the percentage of chains caused by Bub2 overexpression decreased about 10% in zymolase, we examined plasma membrane and cell wall formation after Bub2 overexpression. The plasma membrane was visualized using FM 4–64, and the cell wall was stained using Calcofluor. Examination of chains with three of four cell bodies, formed after eight hours of Bub2 overexpression, showed that chains typically had plasma membrane across some bud necks, but not others (Figure 5A). In contrast, these chains showed a complete lack of cell wall formation at all bud necks (Figure 5C). This result was surprising, since the zymolase assay (Figure 4) suggested greater defects in cytokinesis than septation. Therefore, we repeated the analysis after fifteen hours in YPGR. Most bud necks showed plasma membrane formation between cell bodies, although in some cases the plasma membrane had abnormal bright dots or clumps at the bud neck (Figure 5B). Only the buds at the end of the chains did not have plasma membrane, consistent with being the most recently formed buds. Cell wall formation looked very different after the longer Bub2 induction, with most bud necks now showing septum formation, although in many cases the septa seemed thicker and brighter than normal (Figure 5D). These results suggest that overexpression of the dominant negative Bub2 causes primary septum formation to fail, but over time cells may be able to separate by forming an abnormal secondary septum (see Discussion).

Bub2 overexpression causes a defect in cell wall formation. Wild type cells with GAL1-BUB2 (KSY 129) were grown in YPGR for eight (A. and C.) or fifteen (B. and C.) hours. A. and B. FM4-64 staining to visualize the plasma membrane. Arrow points to closed bud necks. Arrowhead points to abnormal plasma membrane at the bud neck. C. Calcofluor staining shows lack of septum between buds in chains. D. Calcofluor staining shows abnormal septum formation after longer incubation in YPGR (arrowhead). Images are a single plane from a Z series and represent open or closed bud necks as determined from examination of all planes of the series. Scale bar = 5 μm.

Discussion

Regulation of actin ring formation

The MEN pathway in budding yeast regulates cytokinesis as well as exit from mitosis. However, how the MEN controls cytokinesis is not understood. Experimental evidence that actin rings form in apc2–8 bub2Δ cells suggested that the Bub2 checkpoint pathway prevents premature actin ring formation [17, 18]. However, this hypothesis is inconsistent with data showing that Tem1, the target of Bub2 regulation, is not required for actin ring formation [14].

Our examination of actin ring formation in bub2Δ and bfa1Δ strains shows that actin ring formation occurs with normal kinetics in the absence of the Bub2 checkpoint. Although it is possible that Bub2 or Bfa1 has a subtle effect on actin ring formation that was missed by the 10 minute intervals used to examine the cells, this seems unlikely, as our data is consistent with previous results showing that bub2Δ does not advance anaphase onset [5].

Bub2 and Mad2 are required for two separate branches of the mitotic spindle checkpoint in budding yeast. Our data show that cells lacking either one of these checkpoint pathways form actin rings with the same kinetics after nocodazole treatment. Therefore, the delay in actin ring formation in bud2Δ and mad2Δ cells is caused by a cell cycle delay. The actin rings seen in apc2–8 bub2Δ cells [17, 18] are likely due to loss of cell cycle arrest and subsequent downstream events such as actin ring formation. In fact, the authors noted that apc2–8 cells remained arrested in mitosis, while apc2–8 bub2Δ cells exited mitosis after two hours [18]. Therefore, progression through late anaphase, when MEN mutants arrest, is required for actin ring formation, but there is no evidence that the MEN regulates actin ring formation directly.

Our data also do not support a Bub2 independent function of Bfa1 in actin ring formation. There was no apparent difference in the timing of actin ring formation in unperturbed or nocodazole treated cells in isogenic strains with and without a BFA1 deletion.

The MEN and actomyosin ring contraction

One way the MEN may act to regulate cytokinesis is to trigger the onset of myosin contraction. Our data show that deletion of BUB2 or overexpression of a dominant negative Bub2 decreases the total time for contraction of the myosin ring and increases the rate of contraction. This effect on myosin contraction could either be due to direct regulation of contraction by the MEN or an indirect effect caused by defects in primary septum formation. Previous studies have shown that preventing primary septum synthesis results in a cytokinesis failure due to premature breaking and disassembly of the actomyosin ring [22, 23].

We do not think our results are due to indirect effects of septation defects for two reasons. Firstly, we did not see any evidence of abnormal or asymmetrical contraction in bub2Δ or GAL1-T7-Bub2-6His cells, which would be predicted by this model. Secondly, bub2Δ cells showed no evidence of a defect in primary septum formation, yet still exhibited the myosin contraction phenotype. Our results suggest that MEN activation directly influences either the onset or the rate of myosin contraction, and that the Bub2 checkpoint pathway acts as a brake on actomyosin ring contraction. This model is also supported by previous results showing that Tem1 and Mob1 are required for actomyosin ring contraction when the requirement for MEN function in mitotic exit is bypassed [14, 24]. The MEN therefore has a role in promoting cytokinesis that is separate from its role in mitotic kinase inactivation. In contrast, the role of the MEN in promoting primary septum formation depends only on exit from mitosis [25]. The identification of MEN targets involved in the regulation of actomyosin ring contraction will be of great interest. Potential targets include Iqg1, which has been shown to interact with Tem1 in vitro, and Hof1, which is phosphorylated in a MEN-dependent manner [26, 27].

Dominant negative effects of Bub2 overexpression

The GAL1-T7-Bub2-6His construct used in this study has been previously described as partially inhibiting cell growth only in the presence of Bfa1 [19]. It was also reported to cause a chained cell phenotype, although this data was not shown. We have confirmed that this construct causes a mild growth defect as well as a chain phenotype on galactose-containing media in our strain background. However, we did not find that deletion of BFA1 rescued either the growth defect or the chain morphology caused by overexpression of the Bub2 fusion protein. We have further examined the chained cell phenotype, and found evidence for the presence of both cytokinesis and septation defects.

We obtained this construct in the hopes that overexpressing Bub2 would decrease the rate of myosin contraction, since deletion of Bub2 increased the rate. However, we found similar rates of Myo1-GFP contraction in cells expressing T7-Bub2-6His and bub2Δ cells. This is most likely due to the T7-Bub2-6His acting as a dominant negative that interferes with normal Tem1 function. Supporting this conclusion, overexpression of an untagged Bub2 using the GAL1 promoter does not result in a growth defect [28]. Interestingly, overexpression of Bfa1 has a different phenotype than overexpression of either untagged or dominant negative Bub2. Bfa1 overexpression arrests cells in mitosis, and this arrest does not require Bub2 [6, 19].

Causes of cytokinesis and septation defects

Interestingly, we did not observe a correlation between increased rates of myosin contraction and cytokinesis or septation defects. Deletion of BUB2 or overexpression of Bub2 had a similar effect on Myo1-GFP dynamics, but only Bub2 overexpression resulted in the chained cell phenotype. Therefore, the significantly increased rate of myosin contraction we observed does not have an effect on cell morphology under normal growth conditions.

How then does overexpression of a dominant negative Bub2 cause morphological defects? Our data suggest that the T7-Bub2-6His must be affecting Tem1 in a way that does not prevent exit from mitosis, but perturbs septum formation. A temperature sensitive mutant of the MEN kinase Cdc15, cdc15-2, has been shown to have a septation defect when grown at the semipermissive temperature (31°C) [13]. Since binding of Cdc15 to Tem1 is required for Cdc15 activation and prevented by Bub2/Bfa1, the interaction of Cdc15 with Tem1 could be partly inhibited by T7-Bub2-6His overexpression [29, 30].

Zymolase treatment of cells after fifteen hours of Bub2 overexpression resulted in approximately 10% fewer chains than without zymolase, suggesting that some of the chains were due to septation failure, and most of the chains were due to cytokinesis failure. However, staining of plasma membrane and cell wall structures at earlier timepoints showed that lack of septum formation was the primary defect (Figure 5C). Staining at later timepoints indicated that many of the bud necks in the chains had become separated by plasma membrane and chitin, some of which appeared abnormal (Figure 5) and may represent the deposition of thick secondary septa that eventually separate the cells, sometimes trapping pockets of membrane within. Electron microscopy has shown that yeast cells that fail cytokinesis due to lack of myosin and those that fail to form the primary septum due to a lack of chitin synthase have identical phenotypes [23]. In both cases, the cells form a thick cell wall that lack the normal trilaminar structure [23]. It is unclear whether or not zymolase can efficiently digest this abnormally thick septum. Therefore, the zymolase assay may not be able to distinguish failure to contract an actomyosin ring from failure to build a primary septum, since in both cases the cells can eventually separate the plasma membrane by lateral thickening of the cell wall. Additionally, it has been shown that preventing primary septum formation causes instability of the actomyosin ring [22]. Therefore, the two processes of cytokinesis and septation may be so closely linked in budding yeast that defects in one process result in problems in the other.

We think it is likely that the formation of chains of cells after overexpression of a dominant negative Bub2 is caused by a failure to form the primary septum, and that these cells eventually form an abnormal septum as seen previously by EM. The contradictory results from the zymolase assay may be due to incomplete digestion of these thick septal structures, failing to separate the chained cell bodies even though they are separated by plasma membrane. Together, our data suggest that the Bub2 pathway, and therefore the MEN, regulates septation or the coordination of septation with actomyosin ring contraction.

Conclusion

Deletion of BUB2 did not affect the timing of actin ring assembly, but did increase the rate of myosin contraction. Overexpression of a tagged Bub2 protein caused septation defects that were rescued by Tem1 overexpression. Together, the data suggest that the MEN regulates actomyosin ring contraction and septation.

Methods

Yeast media

Yeast cell culture and genetic techniques were carried out by methods described [31]. Yeast cells were grown in YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto peptone, 2% glucose), YPR (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto peptone, 2% raffinose), or YPGR (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto peptone, 2% galactose, 2% raffinose) liquid medium, or on – HIS, -LEU, -TRP or -URA drop-out solid and/or liquid medium at 30°C.

Strain Construction

All S. cerevisiae strains were W303 background, derived from KSY3 (MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-1 ade2 Δbar1). All yeast strains used for this study are listed in Table 2. To create Myo1-GFP expressing strains, pKT36 (MYO1 under its endogenous promoter tagged with GFP on a TRP1 CEN plasmid) [14] was digested with AgeI enzyme and transformed into KSY3, KSY19, KSY51, and KSY129 strains to make KSY 70, 71, 73, and 132 respectively.

To create Bub2 over-expressing strains, pKT1315 (Ro et al., 2001) was digested with NcoI and transformed into KSY3, KSY19 and KSY167 to make KSY129, 130, and 169 respectively. To create the GAL1-myc-TEM1 strain KSY171, pKT25 (GAL1-myc-TEM1 on a LEU2 CEN plasmid) was cut with XcmI and transformed into KSY129. Expression of Bub2 and Tem1 was verified by Western Blot.

To make strains more sensitive to alpha mating factor, the BAR1 locus was replaced by HIS3 or URA3 in strains KSY21, KSY22, KSY24, and KSY25 using PCR-mediated one-step gene replacement [32] using PRS313 or PRS316 as the template and primers as in [33] to make KSY110, KSY111, KSY51, and KSY47 respectively.

Yeast Transformation

Yeast transformations were performed by modified lithium acetate method [34]. After 30 minutes incubation at 30°C, 50 μl of DMSO was added and mixed. Cells were plated on appropriate media and incubated at 30°C for two-three days.

Fluorescence staining of Yeast Cells

KSY3, KSY19, KSY47, KSY51, KSY111 and KSY112 were grown in YPD overnight. α-factor was added to a final concentration of 100 ng/ml for 2 hours to synchronize cells. Cells were washed with sterile dH2O three times and resuspended in YPD or YPD with nocodazole (15 μg/ml final). After release, cells were incubated at 30°C. Cells released into YPD were incubated for 60 to 100 minutes, during this period at every ten minutes, 5 ml of cells were taken and fixed with 670 μl 37% formaldehyde for two hours at room temperature. Cells released in YPD with nocodazole were incubated for 60 to 240 minutes. At 60, 80, 100, 140, 180, 220 240 minutes time points, 5 ml of cells were collected and fixed as above. Fixed cells were stained with Alexa 568 (Invitogen) or rhodamine (Cytoskeleton Inc. Denver, CO) phalloidin as described [21].

Cells were observed using an Olympus IX51 inverted microscope at 1,000× total magnification using a UPLSAPO 100× NA 1.4 objective. A Texas-red filter (Brightline) was used to view phalloidin staining. Images were captured with a Hamamatsu ORCA285 CCD camera. Shutters, filters, and camera were controlled using Slide Book software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO).

Time-lapse microscopy

Cells were grown overnight and placed on agarose pads made by melting 0.2 g of agarose in 1 ml -TRP media [35]. Cells from strain KSY132 were grown overnight in YPR, then arrested with alpha factor with galactose added to 2% final for three hours. Cells were washed 3× with sterile water to release from arrest before imaging. Cells were placed on the agarose pad and covered with cover slip sealed with valap (1:1:1 mixture of Vaseline, lanolin, and paraffin). Living cells were viewed using an Olympus IX51 inverted microscope at 1,000× total magnification using a UPLSAPO 100× NA 1.4 objective. FITC (EX 482/35 506DM EM 536/40) filter was used to visualize GFP (Brightline). Images were captured with a Hamamatsu ORCA285 CCD camera. Shutters, filters, and camera were controlled using Slide Book software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO). Images were collected with exposure (100 ms to 200 ms) to fluorescent light at 1 minute intervals.

Analysis of myosin contraction

To determine the onset of myosin contraction, the time-lapse series of Myo1-GFP expressing cells was viewed at 200% magnification. Time zero was defined as the timepoint after which the ring decreased in diameter. The ruler tool in Slidebook was used to measure the ring at T = 0 and the following frame to confirm that a change in diameter had occurred. A second blind analysis to determine time zero was performed in order to eliminate observer bias. Total time of contraction was the time elapsed between time zero and when the Myo1-GFP signal disappeared from the bud neck. To determine the rate of contraction, the width of the bud neck was measured using the ruler tool in Slidebook and divided by the total time of contraction. Fluorescence intensity profiles were used to examine symmetry of ring contraction. Excel was used to calculate standard deviation and P-values using the two-tailed T test.

Morphological Observations

Cultures of KSY129, 130, 169, and 171 were grown in YPR overnight, then diluted into YPD and YPGR and grown for fifteen hours at 30°C before addition of formaldehyde to 5% final. Fixed cells were treated both with and without zymolyase before observing cells under the microscope for phenotypic changes as described [21]. Morphology was observed and cells were counted under Olympus CH2, objective EA40 NA0.65.

Immunoblot Analysis

Cultures of KSY129, 130, 169, and 171 were grown in YPR overnight, then diluted into either YPD or YPGR and grown for three hours at 30°C before total yeast extracts were prepared by glass bead lysis in SDS sample buffer. Extracts were run on 4–20% Tris-Glycine gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to nitrocellulose. T7-Bub2-6His was detected using anti-T7 antibody diluted 1:1000 (Novagen), and myc-Tem1 was detected using anti-myc monoclonal antibody diluted 1:1000 (Covance). Donkey anti-mouse HRP conjugated secondary antibody was diluted 1:2500 (Jackson ImmunoResearch). The Pierce chemiluminescence detection kit was used (Thermo Scientific). Comparable amounts of total protein were loaded in each lane as shown by Coomassie staining of the same extracts on a separate gel.

Plasma membrane and cell wall staining

To visualize the plasma membrane, FM4–64 (Invitrogen) was added to cells in growth media on ice. For cell wall staining, Calcofluor was used as described [36]. Calcofluor (Fluorescent brightener 28, Sigma) was added to cells in growth medium to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. Cells were incubated 5 minutes, washed twice with H2O, and observed with a DAPI filter set.

References

Hoyt MA: Exit from mitosis: spindle pole power. Cell. 2000, 102 (3): 267-270.

Shah JV, Cleveland DW: Waiting for anaphase: Mad2 and the spindle assembly checkpoint. Cell. 2000, 103 (7): 997-1000.

Alexandru G, Zachariae W, Schleiffer A, Nasmyth K: Sister chromatid separation and chromosome re-duplication are regulated by different mechanisms in response to spindle damage. Embo J. 1999, 18 (10): 2707-2721.

Fesquet D, Fitzpatrick PJ, Johnson AL, Kramer KM, Toyn JH, Johnston LH: A Bub2p-dependent spindle checkpoint pathway regulates the Dbf2p kinase in budding yeast. Embo J. 1999, 18 (9): 2424-2434.

Fraschini R, Formenti E, Lucchini G, Piatti S: Budding yeast Bub2 is localized at spindle pole bodies and activates the mitotic checkpoint via a different pathway from Mad2. J Cell Biol. 1999, 145 (5): 979-991.

Li R: Bifurcation of the mitotic checkpoint pathway in budding yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999, 96 (9): 4989-4994.

Geymonat M, Spanos A, Smith SJ, Wheatley E, Rittinger K, Johnston LH, Sedgwick SG: Control of mitotic exit in budding yeast. In vitro regulation of Tem1 GTPase by Bub2 and Bfa1. J Biol Chem. 2002, 277 (32): 28439-28445.

Shirayama M, Matsui Y, Tanaka K, Toh-e A: Isolation of a CDC25 family gene, MSI2/LTE1, as a multicopy suppressor of ira1. Yeast. 1994, 10 (4): 451-461.

Shirayama M, Matsui Y, Toh EA: The yeast TEM1 gene, which encodes a GTP-binding protein, is involved in termination of M phase. Mol Cell Biol. 1994, 14 (11): 7476-7482.

Balasubramanian MK, McCollum D, Surana U: Tying the knot: linking cytokinesis to the nuclear cycle. J Cell Sci. 2000, 113 (Pt 9): 1503-1513.

Surana U, Amon A, Dowzer C, McGrew J, Byers B, Nasmyth K: Destruction of the CDC28/CLB mitotic kinase is not required for the metaphase to anaphase transition in budding yeast. Embo J. 1993, 12 (5): 1969-1978.

Frenz LM, Lee SE, Fesquet D, Johnston LH: The budding yeast Dbf2 protein kinase localises to the centrosome and moves to the bud neck in late mitosis. J Cell Sci. 2000, 113 (Pt 19): 3399-3408.

Hwa Lim H, Yeong FM, Surana U: Inactivation of mitotic kinase triggers translocation of MEN components to mother-daughter neck in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2003, 14 (11): 4734-4743.

Lippincott J, Shannon KB, Shou W, Deshaies RJ, Li R: The Tem1 small GTPase controls actomyosin and septin dynamics during cytokinesis. J Cell Sci. 2001, 114 (Pt 7): 1379-1386.

Xu S, Huang HK, Kaiser P, Latterich M, Hunter T: Phosphorylation and spindle pole body localization of the Cdc15p mitotic regulatory protein kinase in budding yeast. Curr Biol. 2000, 10 (6): 329-332.

Yoshida S, Toh-e A: Regulation of the localization of Dbf2 and mob1 during cell division of saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Genet Syst. 2001, 76 (2): 141-147.

Lee SE, Frenz LM, Wells NJ, Johnson AL, Johnston LH: Order of function of the budding-yeast mitotic exit-network proteins Tem1, Cdc15, Mob1, Dbf2, and Cdc5. Curr Biol. 2001, 11 (10): 784-788.

Lee SE, Jensen S, Frenz LM, Johnson AL, Fesquet D, Johnston LH: The Bub2-dependent mitotic pathway in yeast acts every cell cycle and regulates cytokinesis. J Cell Sci. 2001, 114 (Pt 12): 2345-2354.

Ro HS, Song S, Lee KS: Bfa1 can regulate Tem1 function independently of Bub2 in the mitotic exit network of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002, 99 (8): 5436-5441.

Bi E, Maddox P, Lew DJ, Salmon ED, McMillan JN, Yeh E, Pringle JR: Involvement of an actomyosin contractile ring in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cytokinesis. J Cell Biol. 1998, 142 (5): 1301-1312.

Lippincott J, Li R: Sequential assembly of myosin II, an IQGAP-like protein, and filamentous actin to a ring structure involved in budding yeast cytokinesis. J Cell Biol. 1998, 140 (2): 355-366.

VerPlank L, Li R: Cell cycle-regulated trafficking of Chs2 controls actomyosin ring stability during cytokinesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2005, 16 (5): 2529-2543.

Schmidt M, Bowers B, Varma A, Roh DH, Cabib E: In budding yeast, contraction of the actomyosin ring and formation of the primary septum at cytokinesis depend on each other. J Cell Sci. 2002, 115 (Pt 2): 293-302.

Luca FC, Mody M, Kurischko C, Roof DM, Giddings TH, Winey M: Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mob1p is required for cytokinesis and mitotic exit. Mol Cell Biol. 2001, 21 (20): 6972-6983.

Zhang G, Kashimshetty R, Ng KE, Tan HB, Yeong FM: Exit from mitosis triggers Chs2p transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to mother-daughter neck via the secretory pathway in budding yeast. J Cell Biol. 2006, 174 (2): 207-220.

Shannon KB, Li R: The multiple roles of Cyk1p in the assembly and function of the actomyosin ring in budding yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1999, 10 (2): 283-296.

Vallen EA, Caviston J, Bi E: Roles of Hof1p, Bni1p, Bnr1p, and myo1p in cytokinesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2000, 11 (2): 593-611.

Fraschini R, D'Ambrosio C, Venturetti M, Lucchini G, Piatti S: Disappearance of the budding yeast Bub2-Bfa1 complex from the mother-bound spindle pole contributes to mitotic exit. J Cell Biol. 2006, 172 (3): 335-346.

Asakawa K, Yoshida S, Otake F, Toh-e A: A novel functional domain of Cdc15 kinase is required for its interaction with Tem1 GTPase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2001, 157 (4): 1437-1450.

Visintin R, Amon A: Regulation of the mitotic exit protein kinases Cdc15 and Dbf2. Mol Biol Cell. 2001, 12 (10): 2961-2974.

Sherman F, Fink G, Lawrence C: Methods in Yeast Genetics. 1974, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Baudin A, Ozier-Kalogeropoulos O, Denouel A, Lacroute F, Cullin C: A simple and efficient method for direct gene deletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993, 21 (14): 3329-3330.

Bieganowski P, Shilinski K, Tsichlis PN, Brenner C: Cdc123 and Checkpoint Forkhead Associated with RING Proteins Control the Cell Cycle by Controlling eIF2{gamma} Abundance. J Biol Chem. 2004, 279 (43): 44656-44666.

Gietz D, St Jean A, Woods RA, Schiestl RH: Improved method for high efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992, 20 (6): 1425-

Waddle JA, Karpova TS, Waterston RH, Cooper JA: Movement of cortical actin patches in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1996, 132 (5): 861-870.

Pringle JR: Staining of bud scars and other cell wall chitin with calcofluor. Methods Enzymol. 1991, 194: 732-735.

Acknowledgements

KBS would like to thank Kyoung Lee for the generous gift of pKL1315, Rong Li for strains and comments on the manuscript, and the Department of Biological Sciences for support. KS was funded by an Opportunities for Undergraduate Research (OURE) fellowship from Missouri S&T. KBS was funded by a Research Board grant from the University of Missouri system.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

SYP made strains, produced a majority of the data, and wrote Methods section. AC performed some of the live cell imaging experiments. JB made additional strains and produced data shown in Figure 4. KS participated in data analysis. KBS planned, supervised, and performed experiments and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12860_2009_392_MOESM1_ESM.mov

Additional File 1: Myo1-GFP in wild type cell. This movie shows myosin contraction in the cell shown in Figure 2A. The movie begins at asterisk in the figure, and was taken at one-minute intervals. (MOV 49 KB)

12860_2009_392_MOESM2_ESM.mov

Additional File 2: Myo1-GFP in a bub2Δ cell. This movie shows myosin contraction in the cell shown in Figure 2B. The movie begins at asterisk in the figure, and was taken at one-minute intervals. (MOV 30 KB)

12860_2009_392_MOESM3_ESM.mov

Additional File 3: Myo1-GFP in a cell overexpressing Bub2. This movie shows myosin contraction in two cells after Bub2 induction by addition of galactose for three hours. The movie was taken at one-minute intervals. (MOV 390 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, S.Y., Cable, A.E., Blair, J. et al. Bub2 regulation of cytokinesis and septation in budding yeast. BMC Cell Biol 10, 43 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2121-10-43

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2121-10-43