Abstract

Background

Ornithine decarboxylase antizymes are proteins which negatively regulate cellular polyamine levels via their affects on polyamine synthesis and cellular uptake. In virtually all organisms from yeast to mammals, antizymes are encoded by two partially overlapping open reading frames (ORFs). A +1 frameshift between frames is required for the synthesis of antizyme. Ribosomes change translation phase at the end of the first ORF in response to stimulatory signals embedded in mRNA. Since standard sequence analysis pipelines are currently unable to recognise sites of programmed ribosomal frameshifting, proper detection of full length antizyme coding sequences (CDS) requires conscientious manual evaluation by a human expert. The rapid growth of sequence information demands less laborious and more cost efficient solutions for this problem. This manuscript describes a rapid and accurate computer tool for antizyme CDS detection that requires minimal human involvement.

Results

We have developed a computer tool, OAF (O DC a ntizyme f inder) for identifying antizyme encoding sequences in spliced or intronless nucleic acid sequenes. OAF utilizes a combination of profile hidden Markov models (HMM) built separately for the products of each open reading frame constituting the entire antizyme coding sequence. Profile HMMs are based on a set of 218 manually assembled antizyme sequences. To distinguish between antizyme paralogs and orthologs from major phyla, antizyme sequences were clustered into twelve groups and specific combinations of profile HMMs were designed for each group. OAF has been tested on the current version of dbEST, where it identified over six thousand Expressed Sequence Tags (EST) sequences encoding antizyme proteins (over two thousand antizyme CDS in these ESTs are non redundant).

Conclusion

OAF performs well on raw EST sequences and mRNA sequences derived from genomic annotations. OAF will be used for the future updates of the RECODE database. OAF can also be useful for identifying novel antizyme sequences when run with relaxed parameters. It is anticipated that OAF will be used for EST and genome annotation purposes. OAF outputs sequence annotations in fasta, genbank flat file or XML format. The OAF web interface and the source code are freely available at http://recode.ucc.ie/oaf/ and at a mirror site http://recode.genetics.utah.edu/oaf/.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ornithine Decarboxylase Antizymes are important negative regulators of cellular polyamine levels. In mammals, antizyme-1 inhibits ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), an enzyme catalyzing the first and rate-limiting step in polyamine biosynthesis. Antizyme-1 binds to ODC and targets it for ubiquitin-independent degradation by the 26S proteosome in a multiple-turnover manner (a single antizyme molecule can cause degradation of several ODC molecules) [1, 2]. Additionally, antizyme-1 regulates the intracellular concentration of polyamines by inhibiting cellular import of polyamines and accelerating polyamine export from the cell [3–5]. While genomes of lower eukaryotes contain single antizyme genes, multiple paralogs have evolved in higher eukaryotes, with at least two antizymes in vertebrates [6, 7], three in mammals [8, 9] and up to five in certain fish species [10]. Antizyme paralogs vary somewhat in their function, although all are implicated in the regulation of polyamine synthesis (and some are reported to link with other pathways [11, 12]). Antizyme paralogs usually have a distinct expression pattern with certain paralogs being expressed in a strictly restrictive tissue-specific manner, such as testis-specific mammalian antizyme 3 [8, 9] or retina and brain specific antizyme AZR from Danio rerio [13]. Reviews of antizyme function and distribution are available [10, 14, 15].

Given the important role that antizymes play in the regulation of polyamine concentrations, it is not surprising that their own biosynthesis is regulated in response to changes of cellular polyamine concentrations. Polyamines' concentrations are sensed during the elongation stage of antizyme mRNA translation. Unlike the great majority of CDS-es, that for virtually all eukaryotic antizymes consists of two overlapping open reading frames. Synthesis of full-length antizyme protein requires a portion of translating ribosomes to switch translation phase at the end of the first ORF into the partially overlapping ORF (in +1 translation phase) in a process termed programmed ribosomal frameshifting [16]. The portion of ribosomes that do not shift frames, terminate at the end of the first ORF with release of relatively short encoded polypeptide. Increases in cellular polyamine levels result in elevated frameshifting efficiency and so of synthesis of fully functional antizyme. The competition between frameshifting and termination at the end of the first ORF is a sensor of polyamine concentration that provides an elegant mechanism for regulatory negative feedback (Figure 1A).

Scheme of negative regulatory feedback in regulation of antizyme synthesis and conservation of the frameshift site. A. The competition between ribosomal frameshifting and standard translation (termination) is sensitive to polyamine levels. An increase in polyamine concentrations shifts the competition toward frameshifting resulting in elevation of antizyme synthesis and consequent inhibition of polyamine synthesis and uptake. A decrease in polyamine concentrations shifts the competition towards standard translation and produces the opposite effect on the synthesis of antizyme and polyamines. B. WebLogo representing the alignment of 153 OAZ sequences. The last codon in the zero frame and the first codon -in +1 frame are indicated by red and blue bars respectively. It can be seen that the only universal nucleotide of the frameshift site is T (U in mRNA) corresponding to the first position of the stop codon at the end of the first ORF.

The +1 frameshifting event during antizyme biosynthesis significantly complicates automatic detection of its full-length CDS in mRNA. This is due to the lack of reliable and efficient algorithms for predicting ribosomal frameshifting locations. A number of attempts have been made recently to develop computational approaches for predicting instances of the ribosomal frameshifting [17–22]. Some of these approaches could be useful for detecting candidate sequences that are prone to efficient (not necessarily programmed) frameshifting within particular groups of organisms [17–19, 23]. However, they are not suitable for reliable detection of programmed ribosomal frameshifting events without experimental verification or additional expert human involvement. The reasons underlying the consistent failure to develop highly accurate algorithms for ribosomal frameshifting prediction lie in the very nature of programmed ribosomal frameshifting. The efficiency of ribosomal frameshifting is modulated by highly diverse sequence elements many of which evolved independently. The mechanisms by which such elements alter translation also vary considerably. The situation is further complicated by differences in the translation machinery (sequences of ribosomal components, differences in tRNAs properties and their relative concentrations) across different organisms, leading to a situation where the same sequence is shift-prone in one organism, but in another it is accurately translated in a standard triplet-manner. Therefore, it is not possible to find even a single nucleotide sequence feature that would specify a site of ribosomal frameshifting universal for all organisms. Information regarding the diversity of genes utilizing programmed ribosomal frameshifting for their expression as well as multifarious sequences modulating frameshifting process is available at the Recode database, which is currently the richest Internet resource [24, 25], as well as, comprehensive literature reviews on this and related topics [26–35]. In fact, currently antizyme mRNAs themselves are the most plentiful source of diverse frameshift stimulator signals as evident from the recent detailed review covering nearly three hundred antizyme mRNA sequences [10]. A collection of sequences described in that review was used here for the design of OAF (Additional file 1).

It appears that approaches to predict frameshifting specifically for particular clusters of related genes produce more reliable results. Such approaches were applied for -1 frameshifting involved in the synthesis of viral polyproteins [21], different types of frameshifting events in decoding bacteriophage tail assembly genes [20], and +1 frameshifting during the synthesis of bacterial release factors 2 [22]. Indeed ribosomal frameshifting utilized by a group of homologous genes likely has the same origin. While evolution introduces organism specific alterations in the sequence of the frameshifting cassette, as well as, diversifying protein sequence, a detectable degree of similarity is frequently recognizable. Though existence of such similarity may not be a universal rule (as evident with the frameshifting utilized in decoding bacteriophage tail assembly genes [20] where only genomic localization of overlapping ORFs is conserved), it holds true for many cases. Therefore, knowledge of a few examples of ribosomal frameshifting from homologous genes can be sufficient for designing algorithms for automatic and accurate prediction of ribosomal frameshifting utilized in decoding of homologous genes. By dealing with each group of homologous genes utilizing ribosomal frameshifting separately one-by-one, we aim to build a collection of autonomic computer tools capable of automatically predicting most cases of ribosomal frameshifting in newly sequenced organisms. OAF is our second computer tool designed in pursuit of this goal. Our first tool, ARFA detects and annotates the programmed ribosomal frameshifting required for expression of certain bacterial release factors [22]. Both tools will be used for future updates of the Recode database.

Implementation

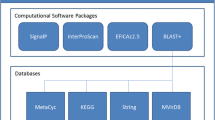

OAF is written in Perl, it utilizes BioPerl libraries [36]. The OAF Web interface was designed using PHP.

Outline of the analysis performed by OAF

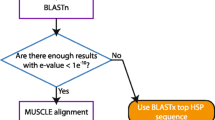

Antizyme mRNAs from different organisms have evolved a remarkable assortment of RNA signals for stimulating or modulating the +1 ribosomal frameshifting used in their expression. Many sequence features are shared among closely related antizyme mRNAs. For example, two distinct types of frameshift-enhancing RNA pseudoknots are embedded in antizyme-1 and antizyme-2 mRNAs from mammals. Nevertheless, not a single feature is universally conserved. Instead of trying to account for known frameshifting stimulators, we have devised an antizyme gene detection scheme based on detection of sequences encoding antizymes. While antizyme protein sequences are highly diverse, there is a reasonable degree of sequence similarity within large phylogenetic groups allowing their detection based on similarity searches. Most importantly, eukaryotic antizyme genes share the same ORF organisation: the upstream ORF is smaller than the downstream ORF and the downstream ORF is always in the +1 translational phase relative to the first one. Therefore our method is based on a search for two overlapping ORFs corresponding to profile HMMs designed using sequences of known antizymes. Mutual orientation of the ORFs is further examined to verify that it corresponds to an expected transition between translational phases. For large sequences (>20 kb), OAF performs an initial FASTA search with relaxed parameters, where a mixture of divergent antizyme sequences is used as a query. This is used to increase OAF speed by reducing the number of candidate sequences for subsequent HMM analysis. Relaxed parameters decrease the chances of losing true positives in this process. The scheme of analyses performed by OAF is illustrated in Figure 2.

Profile HMMs and automatic classification of antizymes

To design profile HMMs exploited by OAF, we used a collection of protein sequences derived from mRNA fragments using manually assembled ESTs. These sequences were described in some detail in a recent antizyme review [10] and are available in this article as an Additional File 1 (manualOAZs.fasta). Evolutionary distances between protein sequences were estimated using a Neighbour-Joining algorithm and poisson correction evolutionary model implemented in MEGA3.1 program [37]. Based on these distances, sequences were clustered into 12 homologous groups for which separate pairs of profile HMMs were designed using HMMER [38]. These HMMs are used to allow discrimination among different antizyme paralogs and to permit approximate estimation of the taxonomic origins of antizyme encoding sequences. The clustering is shown on the tree generated with MEGA3.1 (see Figure 3).

A separate profile HMM is built for the frameshift site itself. This HMM is not used for identification of antizymes or frameshift sites. However a predicted frameshift site is compared to the HMM and corresponding E-score can be reported in the output to facilitate further processing of data such as identification of unusual frameshift sites or detection of sequencing errors disguised as cryptic frameshift sites. Figure 1B illustrates conservation of OAZ frameshift sites as a web logo [39].

OAF I/O interface

Input

There are two types of searches that can be performed by OAF. First a given nucleotide sequence or multiple sequences (either provided in a user's file in a fasta format or as a Genbank accession number) can be analyzed for the presence of antizyme CDS (first two modes in Figure 2). Second (third mode in Figure 2), protein sequences of known antizymes in a user's fasta file can be used as query for a search against a database of nucleotide sequences (either in a local Blast database or in a remote BLAST database at NCBI). A user can specify the genetic code table and usage of alternative initiation codons (by default CDS can start only with ATG/AUG).

Output

OAF reports sequences of encoded antizymes either as raw sequence, or in fasta, genbank or XML format. XML contains detailed information regarding the frameshift site and is compatible with a future version of Recode database. By default, OAF reports all sequences encoding antizymes, even if their ORF organization does not correspond to that for utilization of +1 frameshifting or if only a partial antizyme sequence is found. Such, likely erroneous sequences, can be filtered out automatically.

Web interface

The web interface of OAF (see Availability and Requirements section). It serves mostly illustrative purposes and has limited capabilities compared to a full version of Oaf. Web service allows analysis of a single user-provided sequence for the presence of encoding antizyme.

Results and Discussion

To evaluate OAF prediction sensitivity for genome annotations, the mRNA sequences of 20 completed eukaryotic genomes were downloaded from the RefSeq database [40]. OAF detected 18 OAZ genes (Table 1). No genes encoding antizymes were detected in plant genomes (Table 1). To evaluate OAF prediction selectivity, a random sequence database (totalling 10 Tbp) was generated by a fifth order Markov chains based on six-mer frequencies of each mRNA of the genomic sequences. OAF did not detect any OAZ sequence in this database.

To estimate OAF accuracy on EST sequences, the June 2007 dbEST was used [41]. OAF detected antizyme sequences in 6639 ESTs, among them there are 2067 unique sequences coding for antizyme. Many of these sequences were truncated mRNA fragments that can be grouped as corresponding to the same antizyme mRNA. 24 new antizyme sequences, which were not present in the original dataset (Additional file 1), were detected, see Table 2.

OAF has detected a number of highly similar variant OAZ sequences supported by multiple ESTs corresponding to the same species. Some of these sequences are most likely allelic variants while others correspond to recent gene duplication events. OAZ variants are summarized in Table 3.

OAF detected a number of sequences whose OAZ clustering (Figure 3) did not match the taxonomy of the source organisms. These sequences are likely contaminants that were introduced from pests, symbionts, food or cell hosts (see Table 4). Some of these contaminations were previously reported in [10].

Conclusion

We have developed a simple computer utility for identification of OAZ encoding sequences in nucleic acids, called OAF (O DC a ntizyme f inder). It performs with high speed and accuracy on mRNA sequences annotated in completed genomes as well as on raw RNA sequences from EST collections.

Availability and requirements

* Project name: OAF (O rnithine Decarboxylase A ntizyme F inder)

* Project home pages: http://recode.ucc.ie/oaf/

http://recode.genetics.utah.edu/oaf/

* Operating system(s): Platform independent

* Programming language: Perl, PHP

* Other requirements: Mandatory: BioPerl 1.5.1+, FASTA 3.4+, HMMER 2.3.2. Optional (required for searches against local blast databases): NCBI BLAST

* License: CCL

* Any restrictions to use by non-academics: yes, see the home page.

Abbreviations

- ARFA:

-

Automatic Release Factor Annotation tool

- AZR:

-

AntiZyme from Retina

- BLAST:

-

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

- CDS:

-

CoDing Sequence

- EST:

-

Expressed Sequence Tag

- HMM:

-

Hidden Markov Model

- MEGA:

-

Molecular Evolution Genetic Analysis

- mRNA:

-

messenger RiboNucleic Acid

- NCBI:

-

National Center of Biotechnology and Informatics, Perl: Practical Extraction and Report Language

- PHP:

-

Personal Home Page tools

- OAF:

-

Ornithine decarboxylase Antizyme Finder

- OAZ:

-

Ornithine decarboxylase AntiZyme

- ODC:

-

Ornithine DeCarboxylase

- ORF:

-

Open Reading Frame

- RNA:

-

RiboNucleic Acid

- tRNA:

-

transport RiboNucleic Acid

- URL:

-

Uniform Resource Locator

- XML:

-

eXchange Markup Language.

References

Murakami Y, Matsufuji S, Kameji T, Hayashi S, Igarashi K, Tamura T, Tanaka K, Ichihara A: Ornithine decarboxylase is degraded by the 26S proteasome without ubiquitination. Nature 1992, 360(6404):597–599. 10.1038/360597a0

Zhang M, Pickart CM, Coffino P: Determinants of proteasome recognition of ornithine decarboxylase, a ubiquitin-independent substrate. The EMBO journal 2003, 22(7):1488–1496. 10.1093/emboj/cdg158

Suzuki T, He Y, Kashiwagi K, Murakami Y, Hayashi S, Igarashi K: Antizyme protects against abnormal accumulation and toxicity of polyamines in ornithine decarboxylase-overproducing cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1994, 91(19):8930–8934. 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8930

Mitchell JL, Judd GG, Bareyal-Leyser A, Ling SY: Feedback repression of polyamine transport is mediated by antizyme in mammalian tissue-culture cells. The Biochemical journal 1994, 299(Pt 1):19–22.

Hoshino K, Momiyama E, Yoshida K, Nishimura K, Sakai S, Toida T, Kashiwagi K, Igarashi K: Polyamine transport by mammalian cells and mitochondria: role of antizyme and glycosaminoglycans. The Journal of biological chemistry 2005, 280(52):42801–42808. 10.1074/jbc.M505445200

Ivanov IP, Gesteland RF, Atkins JF: A second mammalian antizyme: conservation of programmed ribosomal frameshifting. Genomics 1998, 52(2):119–129. 10.1006/geno.1998.5434

Zhu C, Lang DW, Coffino P: Antizyme2 is a negative regulator of ornithine decarboxylase and polyamine transport. The Journal of biological chemistry 1999, 274(37):26425–26430. 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26425

Ivanov IP, Rohrwasser A, Terreros DA, Gesteland RF, Atkins JF: Discovery of a spermatogenesis stage-specific ornithine decarboxylase antizyme: antizyme 3. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2000, 97(9):4808–4813. 10.1073/pnas.070055897

Tosaka Y, Tanaka H, Yano Y, Masai K, Nozaki M, Yomogida K, Otani S, Nojima H, Nishimune Y: Identification and characterization of testis specific ornithine decarboxylase antizyme (OAZ-t) gene: expression in haploid germ cells and polyamine-induced frameshifting. Genes Cells 2000, 5(4):265–276. 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00324.x

Ivanov IP, Atkins JF: Ribosomal frameshifting in decoding antizyme mRNAs from yeast and protists to humans: close to 300 cases reveal remarkable diversity despite underlying conservation. Nucleic acids research 2007, 35(6):1842–1858. 10.1093/nar/gkm035

Mangold U, Hayakawa H, Coughlin M, Munger K, Zetter BR: Antizyme, a mediator of ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation and its inhibitor localize to centrosomes and modulate centriole amplification. Oncogene 2007.

Lim SK, Gopalan G: Antizyme1 mediates AURKAIP1-dependent degradation of Aurora-A. Oncogene 2007, 26(46):6593–6603. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210482

Ivanov IP, Pittman AJ, Chien CB, Gesteland RF, Atkins JF: Novel antizyme gene in Danio rerio expressed in brain and retina. Gene 2007, 387(1–2):87–92. 10.1016/j.gene.2006.08.016

Hayashi S, Murakami Y, Matsufuji S: Ornithine decarboxylase antizyme: a novel type of regulatory protein. Trends in biochemical sciences 1996, 21(1):27–30.

Coffino P: Regulation of cellular polyamines by antizyme. Nature reviews 2001, 2(3):188–194. 10.1038/35056508

Matsufuji S, Matsufuji T, Miyazaki Y, Murakami Y, Atkins JF, Gesteland RF, Hayashi S: Autoregulatory frameshifting in decoding mammalian ornithine decarboxylase antizyme. Cell 1995, 80(1):51–60. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90450-6

Moon S, Byun Y, Kim HJ, Jeong S, Han K: Predicting genes expressed via -1 and +1 frameshifts. Nucleic acids research 2004, 32(16):4884–4892. 10.1093/nar/gkh829

Hammell AB, Taylor RC, Peltz SW, Dinman JD: Identification of putative programmed -1 ribosomal frameshift signals in large DNA databases. Genome research 1999, 9(5):417–427.

Shah AA, Giddings MC, Parvaz JB, Gesteland RF, Atkins JF, Ivanov IP: Computational identification of putative programmed translational frameshift sites. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2002, 18(8):1046–1053. 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.8.1046

Xu J, Hendrix RW, Duda RL: Conserved translational frameshift in dsDNA bacteriophage tail assembly genes. Molecular cell 2004, 16(1):11–21. 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.006

Bekaert M, Rousset JP: An extended signal involved in eukaryotic -1 frameshifting operates through modification of the E site tRNA. Molecular cell 2005, 17(1):61–68. 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.009

Bekaert M, Atkins JF, Baranov PV: ARFA: a program for annotating bacterial release factor genes, including prediction of programmed ribosomal frameshifting. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2006, 22(20):2463–2465. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl430

Jacobs JL, Belew AT, Rakauskaite R, Dinman JD: Identification of functional, endogenous programmed -1 ribosomal frameshift signals in the genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic acids research 2007, 35(1):165–174. 10.1093/nar/gkl1033

Baranov PV, Gurvich OL, Fayet O, Prere MF, Miller WA, Gesteland RF, Atkins JF, Giddings MC: RECODE: a database of frameshifting, bypassing and codon redefinition utilized for gene expression. Nucleic acids research 2001, 29(1):264–267. 10.1093/nar/29.1.264

Baranov PV, Gurvich OL, Hammer AW, Gesteland RF, Atkins JF: Recode 2003. Nucleic acids research 2003, 31(1):87–89. 10.1093/nar/gkg024

Gesteland RF, Atkins JF: Recoding: dynamic reprogramming of translation. Annual review of biochemistry 1996, 65: 741–768. 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.003521

Farabaugh PJ: Programmed translational frameshifting. Annual review of genetics 1996, 30: 507–528. 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.507

Giedroc DP, Theimer CA, Nixon PL: Structure, stability and function of RNA pseudoknots involved in stimulating ribosomal frameshifting. Journal of molecular biology 2000, 298(2):167–185. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3668

Brierley I, Pennell S: Structure and function of the stimulatory RNAs involved in programmed eukaryotic-1 ribosomal frameshifting. Cold Spring Harbor symposia on quantitative biology 2001, 66: 233–248. 10.1101/sqb.2001.66.233

Stahl G, Ben Salem S, Li Z, McCarty G, Raman A, Shah M, Farabaugh PJ: Programmed +1 translational frameshifting in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae results from disruption of translational error correction. Cold Spring Harbor symposia on quantitative biology 2001, 66: 249–258. 10.1101/sqb.2001.66.249

Baranov PV, Gesteland RF, Atkins JF: Recoding: translational bifurcations in gene expression. Gene 2002, 286(2):187–201. 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)00423-7

Klobutcher LA, Farabaugh PJ: Shifty ciliates: frequent programmed translational frameshifting in euplotids. Cell 2002, 111(6):763–766. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01138-8

Baranov PV, Gesteland RF, Atkins JF: P-site tRNA is a crucial initiator of ribosomal frameshifting. RNA (New York, NY) 2004, 10(2):221–230.

Namy O, Rousset JP, Napthine S, Brierley I: Reprogrammed genetic decoding in cellular gene expression. Molecular cell 2004, 13(2):157–168. 10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00031-0

Baranov PV, Fayet O, Hendrix RW, Atkins JF: Recoding in bacteriophages and bacterial IS elements. Trends Genet 2006, 22(3):174–181. 10.1016/j.tig.2006.01.005

Stajich JE, Block D, Boulez K, Brenner SE, Chervitz SA, Dagdigian C, Fuellen G, Gilbert JG, Korf I, Lapp H, et al.: The Bioperl toolkit: Perl modules for the life sciences. Genome research 2002, 12(10):1611–1618. 10.1101/gr.361602

Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M: MEGA3: Integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Briefings in bioinformatics 2004, 5(2):150–163. 10.1093/bib/5.2.150

HMMER[http://hmmer.janelia.org]

Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE: WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome research 2004, 14(6):1188–1190. 10.1101/gr.849004

Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Maglott DR: NCBI reference sequences (RefSeq): a curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic acids research 2007, (35 Database):D61–65. 10.1093/nar/gkl842

Boguski MS, Lowe TM, Tolstoshev CM: dbEST – database for "expressed sequence tags". Nature genetics 1993, 4(4):332–333. 10.1038/ng0893-332

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge continuous excellent support of RECODE database computational resources by IT staff at the Human Genetics Department, University of Utah lead by Rick Haycock. This work is supported by grants from Science Foundation Ireland to JFA and PVB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MB designed and scripted OAF and its web interface. IPI manually reconstructed antizyme mRNA sequences from EST collections. JFA provided encouragement, general coordination and financial support to the project. PVB conceived the project, helped to design OAF and wrote the manuscript. All authors have contributed to the final revision of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12859_2007_2163_MOESM1_ESM.fast

Additional file 1: Collection of OAZ sequences. Manually collected and assembled OAZ sequences that were used to device OAF. (FAST 103 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bekaert, M., Ivanov, I.P., Atkins, J.F. et al. Ornithine decarboxylase antizyme finder (OAF): Fast and reliable detection of antizymes with frameshifts in mRNAs. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 178 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-9-178

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-9-178