Abstract

Background

The kelch motif is an ancient and evolutionarily-widespread sequence motif of 44–56 amino acids in length. It occurs as five to seven repeats that form a β-propeller tertiary structure. Over 28 kelch-repeat proteins have been sequenced and functionally characterised from diverse organisms spanning from viruses, plants and fungi to mammals and it is evident from expressed sequence tag, domain and genome databases that many additional hypothetical proteins contain kelch-repeats. In general, kelch-repeat β-propellers are involved in protein-protein interactions, however the modest sequence identity between kelch motifs, the diversity of domain architectures, and the partial information on this protein family in any single species, all present difficulties to developing a coherent view of the kelch-repeat domain and the kelch-repeat protein superfamily. To understand the complexity of this superfamily of proteins, we have analysed by bioinformatics the complement of kelch-repeat proteins encoded in the human genome and have made comparisons to the kelch-repeat proteins encoded in other sequenced genomes.

Results

We identified 71 kelch-repeat proteins encoded in the human genome, whereas 5 or 8 members were identified in yeasts and around 18 in C. elegans, D. melanogaster and A. gambiae. Multiple domain architectures were identified in each organism, including previously unrecognised forms. The vast majority of kelch-repeat domains are predicted to form six-bladed β-propellers. The most prevalent domain architecture in the metazoan animal genomes studied was the BTB/kelch domain organisation and we uncovered 3 subgroups of human BTB/kelch proteins. Sequence analysis of the kelch-repeat domains of the most robustly-related subgroups identified differences in β-propeller organisation that could provide direction for experimental study of protein-binding characteristics.

Conclusion

The kelch-repeat superfamily constitutes a distinct and evolutionarily-widespread family of β-propeller domain-containing proteins. Expansion of the family during the evolution of multicellular animals is mainly accounted for by a major expansion of the BTB/kelch domain architecture. BTB/kelch proteins constitute 72 % of the kelch-repeat superfamily of H. sapiens and form three subgroups, one of which appears the most-conserved during evolution. Distinctions in propeller blade organisation between subgroups 1 and 2 were identified that could provide new direction for biochemical and functional studies of novel kelch-repeat proteins.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The kelch motif is an ancient and evolutionarily-widespread sequence motif of 44–56 amino acids in length. Eight residues within the motif are highly-conserved and constitute a consensus sequence [1–3] (Fig. 1A). Kelch motifs occur as groups of five to seven repeats and have been identified in proteins of otherwise distinct molecular architecture, termed the kelch-repeat superfamily. Currently, over 28 kelch-repeat proteins have been sequenced and functionally characterised in diverse organisms including viruses, plants, fungi and mammals [3]. Several kelch repeat-containing proteins have been recognised in Bacteria and Archaea (GenBank NP_713516, NP_639451 and Pfam01344 species distribution link), revealing the universal nature of the repeats. On the basis of the crystal structure determined for a single kelch-repeat protein, Hypomyces rosellus galactose oxidase (PDB 1GOF), the sets of repeated kelch motifs are predicated to form a β-propeller structure [2, 4].

The kelch motif and the β-propeller fold. A, Consensus sequence of the kelch motif. Compiled from [2] and [3]. The sequence motif is shown in relation to the four β-sheets of a propeller blade structure, as determined for the kelch motifs of fungal galactose oxidase [4]. In the consensus, G= glycine, Y = tyrosine, W = tryptophan, s = small residue; l = large residue; h = hydrophobic residue. B, Structure of a kelch-repeat propeller blade. A single blade from the crystal structure of fungal galactose oxidase (1GOF) is shown. β sheets 1–4 are colored as in panel A. The N- and C-termini join to adjacent blades. As indicated by the mapping of the consensus amino acids onto the blade, the most highly-conserved residues are located in the β-sheets. In various examples of β-propeller proteins, the intra- and inter-blade loops have variable sequences and contribute to protein-protein interactions [3]. C, Structure of the kelch-repeat β-propeller domain of fungal galactose oxidase (1GOF). β-sheets 1–4 in each blade are colored as in panel A. As indicated, this β-propeller contains seven blades. The β-4 strand of blade 7 is derived from the amino-terminus of the domain and thus closes the circular structure.

The β-propeller is a widespread and universal protein domain fold, as revealed from crystal structures of diverse proteins [5–7]. Many unrelated primary sequences can adopt the stereotypical topology of a β-propeller; however, several sequence repeat motifs have been identified in relation to known crystal structures that are predictors of propeller domains. These include the WD motif, the regulator of chromosome condensation 1 (RCC1) motif and the tachylectin-2 repeat, as well as the kelch motif [3, 5–9]. Each "blade" of a β-propeller structure is formed from a four-stranded antiparallel twisted β-sheet fold, in which each β-sheet packs onto the adjoining sheets through hydrophobic contacts (Fig. 1B). Four to eight of these β-sheet modules are radially arranged around a central axis to form the β-propeller domain, with the twist of the β-sheets within each module producing the propeller-blade appearance (Fig. 1C). Intra- and inter-blade loops of varying lengths protrude above, below, or at the sides of the β-sheets and contribute variability to the binding properties of individual β-propellers [3, 5, 6] (Fig. 1B). The whole structure is closed and stabilised by interactions between the first and last blades. In the four-bladed β-propellers of hemopexin and collagenase this is achieved by disulphide bonding between the first and last blades [10, 11]. In the other examples for which there is crystal structural information, the last blade of the β-propeller is assembled as a composite from sequences at the amino- and carboxy-terminal ends of the domain, that are held together by hydrogen bonds [3, 5, 6, 9] (example of galactose oxidase shown in Fig. 1C).

Kelch-repeat β-propellers undergo a variety of binding interactions with other molecules. Several kelch proteins, including D. melanogaster kelch and mammalian IPP, bind and cross-link F-actin through the β-propeller domain [12, 13]. In contrast, the kelch repeats of other proteins, such as gigaxonin, Keap1, or recombination-activating gene 2, (RAG-2), have unique binding partner proteins [14–16] and the β-propeller of fungal galactose oxidase corresponds to the catalytic domain of the enzyme [2, 4]. The kelch-repeat β-propeller is thus considered to form a general protein-protein interaction module that associates with diverse and specific binding partners [3]. Several kelch-repeat proteins contain other protein domains, of particular note being the Broad-Complex, Tramtrack, and Bric-a-Brac/Poxvirus and Zincfinger (BTB/POZ) domain (CDD6184, Pfam 00651, SMART0225) [1, 3, 17]. The BTB/POZ domain was first identified as a dimerisation domain of transcription factors and also mediates homodimerisation of kelch and other BTB/kelch domain proteins [10, 17, 18].

As summarised above, the current view of the kelch-repeat superfamily has been compiled from studies of individual kelch-repeat proteins from diverse organisms. The extent and complexity of the kelch-repeat family within an individual species is unknown. An overview of this domain family would be of value in order to make a rational assignment of structural subgroups and to develop a coherent perspective on the evolution of this protein domain between modern organisms. A clear view of kelch-repeat proteins could also open up new possibilities for sequence analysis, prediction and experimental analysis of structure/function relationships, and a greater understanding of the specific properties of kelch-repeat proteins within the large β-propeller fold group. In modern life sciences, such molecular information provides a fundamental context for well-targeted biochemical and biological studies of individual proteins. Building on the availability of complete genome sequence information for H. sapiens, D. melanogaster, A. gambiae, C. elegans, S. cerevisiae, S. pombe and A. thaliana we have addressed these questions through database mining and bioinformatic sequence analyses.

Results

Identification and characterisation of kelch-repeat proteins encoded in the human genome

To identify the kelch-repeat proteins encoded in the human genome, BLAST and PSI-BLAST searches of the human genome predicted protein database were carried out with the kelch-motif consensus (CDD543, Pfam01344, SMART 00612) as a query sequence. This search identified 57 kelch-repeat proteins and hypothetical proteins. We noted that several of the known human kelch-repeat proteins [3] were not identified by this method, probably because there are relatively few consensus residues in each kelch motif, none of which is completely invariant across all examples of the motif, and also because of variation in the lengths of the loops between the β-strands [2, 3, 6]. Therefore further searches were made with the kelch-repeats of all 28 known superfamily members, as described in the Methods. These searches identified 18 additional kelch-repeat proteins encoded in the human genome. Cross referencing all 75 entries against GenBank identified 9 of the entries as partial sequences and/or duplicate entries for the same protein or hypothetical ORF, and two of the entries as non-kelch containing proteins. We also cross-referenced the search results to the domain entries for kelch in the Pfam [19] and SMART [20] domain databases. Many entries were listed in both SMART and Pfam, however a number of the proteins we had identified were not listed in these databases (indicated in Table 1), even though when we searched these polypeptides against SMART or Pfam, kelch motifs were clearly identified. Furthermore, the numbers of kelch repeat proteins assigned to H. sapiens in the Species tree or Taxbreak links of Pfam and SMART were over-estimated because of inclusion of incomplete ORFs and multiple entries for the same polypeptide. We also carried out additional searches of GenBank with single kelch motifs from the 28 known kelch-repeat proteins that were distinctly longer than the CDD kelch-motif consensus, in order to search more extensively for proteins containing more divergent repeats. From these multiple evaluations and with exclusion of partial sequences (as described in the Methods), we identified at least 71 kelch-repeat proteins encoded in the human genome (Table 1).

To determine the number of repeated kelch motifs in each protein or hypothetical protein, BLASTP searches were made with each sequence against the Conserved Domain Database (CDD) and Pfam, together with manual identification of kelch motifs. The number of kelch motifs identified varied from two to seven. Four blades is the minumum number that has been documented from crystal structures of β-propeller domains [5, 6, 8, 9]. Thus, it appeared unlikely that entries encoding two or three kelch motifs corresponded to complete ORFs and these were excluded from further analysis (entries NP-689579, XP_209285, XP_058629). On this basis, 12.7 % (9/71) of sequences were predicted to contain five-bladed β-propellers, 84.5 % (60/71) to be six-bladed, and 2.8 % (2/71) to contain seven-bladed β-propellers (Table 1). To our knowledge, only one seven-bladed kelch repeat protein has been identified previously, fungal galactose oxidase [2, 4].

In galactose oxidase, the single kelch-repeat protein for which there is crystal structure information, the propeller is circularised by formation of a composite seventh blade, with the β-one to β-three strands provided from the most C-terminal sequence repeat and the β-four strand provided by sequence amino-terminal to the first full sequence repeat, a mechanism referred to as "N-terminal β-strand closure" [3, 4], (Fig. 1C). We examined the the human kelch-repeat proteins by secondary structure prediction of β-sheets and by manual analysis of the sequence repeats, and found that for 77.5 % (55/71) of the proteins the β-propeller structure was predicted to be closed by a C-terminal β-strand. For five sequences, no clear prediction could be made (Table 1).

Chromosomal localisation of Human kelch-repeat proteins

The encoding sequences for human kelch-repeat proteins are dispersed throughout the genome, being located on all chromosomes except chromosome 21 and the Y chromosome (Table 1). Several instances of genes in physical proximity were noticed, for example NP_006460 and NP_067646 at 1q31.3 and NP_569713 and NP_060114 at 3q27.3 (Table 1). However, in the majority of cases these did not correspond to the most closely-related protein sequences as would be expected for recently-duplicated genes. One exception was NP_055130 and NP-751943 which were located at 14q21.3 and which were the most closely-related to each other (46 % identity). Overall, there was no evidence for physical grouping of kelch-protein encoding sequences within the human genome. In contrast, genes encoding the numerous F-box/kelch proteins of A. thaliana are clustered such that some of the most highly-related sequences are encoded from physically close genomic locations [21, 22].

Domain Architecture of Human Kelch-repeat proteins

Twenty-eight kelch-repeat proteins from various organisms were previously grouped into 5 structural categories according to the positioning of the kelch repeats within the polypeptide sequence and the presence of other conserved structural domains [3]. To evaluate the complexity of domain architectures within a single organism, each human kelch-repeat protein sequence was re-analysed by searching against CDD, SMART and Pfam and then subgrouped according to domain architecture.

Strikingly, 72 % (51/71) of the human kelch-repeat proteins contained a BTB/POZ domain. In all but one of the proteins, the BTB domain was amino-terminal to the kelch domain (Table 1). This hypothetical protein, LZTR-1, contained two tandem BTB domains. Four (5.6%) kelch-repeat proteins contained a single additional conserved domain. Muskelin was the only kelch-repeat protein identified in the human genome to contain a discoidin domain (CDD 7753, Pfam 00231, SMART 00231, also known as F5/F8 type C domain) (Prag, Collett and Adams, in preparation). The discoidin domain acts as a protein-protein interaction domain in a number of extracellular and intracellular proteins and, in clotting factors V and VIII, mediates phospholipid binding [23]. Another kelch-protein, XP_048774, contained a F-box domain (CDD9197, Pfam 00646). The F-box is a domain of about forty residues, first identified in cyclin A, that interacts with Skp1 to anchor proteins to the ubiquitin-ligase assembly for ubiquitination and targeting to proteosome-mediated degradation [24]. The combination of F-box and kelch-repeat domains has previously been described in A. thaliana, where at least 67 F-box/kelch proteins and hypothetical proteins are encoded in the genome [21, 22]. Several of these function in light-dependent regulation of the circadian clock, but the function of many others is obscure [21, 22, 25]. To our knowledge, this is the first recognition of a F-box/kelch protein in an animal genome. One predicted kelch-repeat protein, NP_055608, contained a leucine carboxyl methyltansferase (LCM) domain (CDD9631, Pfam 04072) with 34% identity to the LCM domain of protein phosphatase 2 leucine carboxyl methyltransferase [26]. Recombination-activating gene-2 (RAG-2) contains a plant homeodomain (PHD) finger domain (Pfam00628) at the carboxy-terminus [16].

Six kelch-repeat proteins (11 %) were very large, multidomain proteins (Table 1). Attractin/mahogany (that are splice variants from a single gene; 27–29) and MEGF8 are each over 1000 amino acids long and contained a CUB-domain, kelch repeats, a C-type lectin domain and EGF-like domains. Diverse functions have been attributed to attractin and mahogany that include a role in T-cell interactions (attractin, the secreted splice variant) [27] and obesity regulation in mice (mahogany, the transmembrane splice variant) [28, 29]. Host cell factor-1 and -2 (HCF-1 and HCF-2) are also large proteins which contain amino-terminal kelch-repeats, two fibronectin type III domains and, in the case of HCF-1, a series of unique HCF repeats. These proteins function as transcriptional coactivators of herpes simplex virus immediate early gene expression [30, 31].

We identified three hypothetical kelch-repeat proteins as containing unrelated unique sequences that did not correspond to recognised structural domains, positioned either amino- or carboxy-terminal to the kelch repeats (Table 1).

Rab9 effector p40 [32] and six other kelch-repeat proteins were short polypeptides, from 350–442 amino acids in length, that consisted almost entirely of kelch repeats (Table 1). Five of these proteins or hypothetical proteins, including p40, contained six sequence repeats and thus are predicted to form six-bladed β-propellers. Two hypothetical proteins, NP_060673 and XP_114323, consisted of putative seven-bladed β-propellers. Together, these structural distinctions form the basis for the novel categorisation of human kelch-repeat proteins that is presented here (Table 1).

Structural relationships of human BTB/kelch proteins

The unexpectedly large number of BTB/kelch proteins encoded in the human genome prompted us to study this group in more detail, with the aim of identifying structural subgroups that might also represent functional subsets. The 38 full-length sequences that contained single BTB domains and predicted six-bladed β-propellers were aligned according to sequence similarity in CLUSTALW and viewed as neighbourhood-joining trees. Alignment of the full-length sequences revealed three subgroups of approximately equal size, which we termed subgroups 1 to 3 (Fig. 2A). When the same analysis was performed with the kelch domains alone, the same grouping was apparent for subgroup 1 and a substantial proportion of subgroup 2, termed subgroup 2A (Fig. 2B). In an alignment of the BTB domains only, subgroups 1 and 2 were maintained for the majority of sequences (Fig. 2C). Unrooted trees produced by a separate method for alignment based on maximum parsimony analysis of sequences, PROTPARS, did not support subgroup 3 but consistently demonstrated the relationship of the sequences in subgroups 1 and 2A (data not shown). We focused on these robustly-related kelch-repeat sequences in subgroups 1 and 2A, for a closer analysis of the kelch-repeat domains.

Relationships between human BTB/kelch proteins. The amino acid sequences of the 38 full-length human BTB/kelch proteins predicted to contain six-bladed β-propellers were aligned in CLUSTALW and are presented in Phylip Drawgram for A) full-length sequences; B) kelch-repeat domains only; C) BTB domains only, with shade codes for the three identified subgroups as indicated. Asterisk in panel A indicate known actin-binding BTB/kelch proteins. Panel B shows the robust grouping of a set of sequences from subgroup 2, termed subgroup 2A.

CLUSTALW multiple sequence alignment of the kelch-repeat domains from each of subgroups 1 and 2A demonstrated distinctive features in terms of repeat organisation. In both subgroups (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4), the intrablade loop between β-strands 2 and 3 (the 2–3 loop, Fig. 5A) and the interblade 4–1 loop were major sources of variation within the repeats with regard to their length and primary structure. In the context of an intact β-propeller domain, the 1–2 and 3–4 loops protrude above one face of the β-sheets and the 2–3 loop protrudes from the opposite face (Fig. 5A). The 4–1 loop lies either on the same face as the 2–3 loop, or may be positioned more closely to the β-sheet core of the propeller (Fig. 5). In subgroup 1, the longest 2–3 loops were found in repeats 1, 5 and 6, with shorter loops in blades 2, 3 and 4. The longest 4–1 loop were that between repeats 5 and 6 (Fig. 3). In the context of a β-propeller, this suggests that the side of the propeller formed by repeats 5, 6 and 1 may be particularly involved in protein interactions (see Fig. 1C). In subgroup 2A, the longest 2–3 loops were those in repeats 1 and 2, repeats 4 and 5 had intermediate 2–3 loops and repeats 3 and 6 contained the shortest 2–3 loops. The longest 4–1 loops were those between repeats 1 and 2, and repeats 3 and 4 (Fig. 4). This suggests that there is a different organisation of binding sites in subgroup 2A β-propellers, with perhaps two binding faces formed by repeats 1 and 2, and repeats 4 and 5. At the level of individual sequences, there were also specific examples of variation from the standard repeat organisation that could be of functional importance for individual proteins. For example, NP_695002 in subgroup 2A has an unusually long and highly charged 3–4 loop in repeat 1 and XP_ 040383 has a long 3–4 loop in repeat 4 (Fig. 4).

Multiple sequence alignment of subgroup 1 human BTB/kelch proteins. The kelch-repeat domains of the 15 subgroup 1 BTB/kelch proteins were aligned in CLUSTALW to generate a 50 % identity threshold level consensus sequence. The alignments are presented for each repeat, with the repeat unit assigned according to the 1GOF structure. The four β-strands in each repeat are color-coded as in Fig. 1A. Alignments are presented in Boxshade: black shading indicates identical amino acids, grey shading indicates similar amino acids and white background indicates unrelated amino acids.

Multiple sequence alignment of subgroup 2A human BTB/kelch proteins. The kelch-repeat domains of the 10 subgroup 2A BTB/kelch proteins were aligned in CLUSTALW to generate a 50 % identity threshold level consensus sequence. The alignments are presented for each repeat, with the repeat unit assigned according to the 1GOF structure. The four β-strands in each repeat are color-coded as in Fig. 1A. Alignments are presented in Boxshade: black shading indicates identical amino acids, grey shading indicates similar amino acids and white background indicates unrelated amino acids.

Relationships of consensus kelch-motifs to propeller blade structure. A, Side view of single propeller blade structure from galactose oxidase (1GOF). β-strands are color-coded as in Fig. 1A and the nomenclature for the intra- and inter-blade loops is indicated. B, Alignment of consensus kelch motifs derived from BTB/kelch subgroups 1 and 2A to blade structure, demonstrating distinctions in the 2–3 loop size and charge distribution. The position of each β-strand is indicated.

We also found that the consensus sequences for the fold were distinctive between the two subgroups. The 50 % identity consensus sequence from each subgroup was realigned against the kelch-repeat unit to derive mean 50 % identity consensus sequences for subgroup 1 and subgroup 2A. These motifs were mapped against the known blade structure of galactose oxidase (Fig. 5). The consensus motifs included both amino acids of importance to the fold (located within the β-strands) and certain amino acids within loops, that would be predicted to contribute to binding interactions. Of note, the average length of the motif was shorter in subgroup 1 than subgroup 2A. The subgroup 2A consensus is predicted to contain a longer 2–3 loop. The consensus motifs were distinct in the positioning of highly-conserved charged residues within the loop regions (Fig. 5). The conservation of these charged residues was most pronounced in subgroup 1, where these positions were conserved in the motif to the 70 % identity threshold level (data not shown). These distinctions in loop characteristics are also suggestive of different modalities of protein-protein interactions for the β-propellers of subgroups 1 and 2A. With regard to previously-characterised protein-binding properties, we observed that the BTB/kelch proteins that bind to actin were split between subgroups 1 and 3; thus this function does not have a simple relationship to the primary structure (Fig. 2A).

Kelch-repeat Proteins encoded in invertebrate genomes

We wished to compare the evolutionary development of kelch-repeat proteins between humans and modern invertebrates, and so repeated the analysis of kelch-repeat proteins and their structural subgroups encoded in the genomes of D. melanogaster, A. gambiae and C. elegans [33–35]. We identified 18 kelch-repeat proteins encoded in the Drosophila and Anopheles genomes (Table 2). Seventeen of these were orthologues conserved between the two species (the average identity between orthologous genes of D. melanogaster and A. gambiae is 56 % [36]) and one was unique to each species. Thus, an Actinfilin homologue was identified in A. gambiae but not in D. melanogaster and the D. melanogaster genome contained a homologue of NP_116164 which was not present in A. gambiae (Table 2). Only three kelch-repeat proteins were previously characterised in D. melanogaster, namely Kelch [1, 37], Muskelin [38] and Drosophila host cell factor [39]. Two others, diablo and scruin-like at the midline (SLIM-1), have been recognised as kelch-repeat proteins [33].

Within the group of 19 proteins and hypothetical proteins, 95 % contained six kelch-repeats. Only one protein with five kelch-repeats was identified in either D. melanogaster or A. gambiae, which corresponded to an orthologue of the human F-box/kelch protein, XP_048774 (Table 2). 56 % of the kelch-repeat proteins of D. melanogaster and A. gambiae were BTB/kelch proteins. Both D. melanogaster and A. gambiae contained one discoidin/kelch protein orthologous to muskelin, one F-box/kelch protein, three kelch and multidomain proteins, one kelch and unique protein, and two propeller-only proteins. Thus, all of the 19 kelch-repeat proteins identified had homologues in the human genome and the BTB/kelch domain architecture was the most prevalent (Table 2).

We identified 16 kelch-repeat proteins encoded within the C. elegans genome (Table 3). Of these proteins, only kel-1, spe-26 and CeHCF have been functionally characterised. Kel-1 is an intracellular protein involved in the regulation of feeding behavior during larval development [40]. Spe-26 contributes to the cellular organisation of spermatocytes and mutations are associated with sterility [41]. CeHCF might be involved in the regulation of cell proliferation [42–44]. 43.7 % (7/16) of the proteins had the BTB/kelch domain architecture, two were homologues of HCF and attractin with similar multidomain architectures, two contained unique sequences outside of the kelch repeats and two were propeller-only proteins, both of which were predicted to form six-bladed β-propellers. A single F-box/kelch protein was identified, but no muskelin-like protein was found (Table 3), [34]. Instead, two hypothetical proteins with distinctive domain architectures were identified : NP_506605 which also contained a cyclin carboxy-terminal domain (CDD 7965, Pfam 02984, SMART 00385) and NP_506602, that contained a RING domain (CDD 8941, Pfam 00097, SMART 00184). The cyclin carboxy-terminal domain forms an α-helical fold that may constitute a protein interaction site [45]. The RING domain is a zinc-finger fold that mediates protein-protein interactions [46].

Kelch-repeat Proteins encoded in yeast genomes

Several kelch-repeat proteins have been studied functionally in budding and fission yeast but none of these correspond to BTB/kelch proteins [3, 47, 48]. We investigated whether the prevalance of the BTB/kelch domain architecture we had identified in multicellular animals extended to yeast, by analysing the complement of kelch-repeat proteins encoded in the S. pombe and S. cerevisiae genomes [49, 50]. We found that each genome encoded a small number of kelch-repeat proteins (five in S. pombe, eight in S. cerevisiae), none of which corresponded to a BTB/kelch protein (Table 4). Proteins and hypothetical proteins consisting of an amino-terminal kelch β-propeller and an extended coiled-coil region [3, 47, 48] and a protein corresponding to a putative leucine carboxyl methyltransferase [26] were common to S. pombe and S. cerevisiae. The other encoded kelch-repeat proteins were non-homologous (Table 4). Muskelin-like 1 protein and Ral-2p were identified in S. pombe but not S. cerevisiae [38, 51]. Two proteins with distantly-related kelch repeats, Gpb1/Krh1 and Gpb2/Krh2, have been characterised functionally as G protein-coupled receptor-binding proteins in S. cerevisiae [52, 53]. Homologous proteins were not identified in S. pombe in the context of our study. Thus, the BTB/kelch domain architecture was not identified in these yeasts.

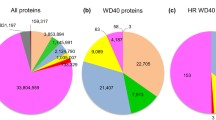

Restriction of BTB/kelch proteins to metazoan animals and poxviruses

Because the BTB/kelch domain architecture appeared prevalent in animals but was not identified in yeast we were interested to consider if any other organisms might contain kelch-repeat proteins with this domain architecture. A number of BTB/kelch proteins have been reported as hypothetical open reading frames (ORFs) in the poxvirus family of animal viruses [54]. The Conserved Domain Architecture Retrieval Tool (CDART) database at NCBI lists 333 entries for BTB/kelch proteins, all of which originate from vertebrates, insects, C. elegans or poxviruses. To date, the BTB domain has only been identified in eucaryotes (Pfam 00651 species tree). In addition to reviewing the SMART and Pfam species trees for categorisation of the BTB/kelch domain architecture, we conducted our own BLASTP and TBLASTX searches of the A. thaliana genome database [55] with the CDD kelch motif consensus (this search tool identified 44 BTB/kelch proteins from the human genome and is thus very effective in uncovering these proteins) and identified 72 protein sequences, the majority of which were F-box/kelch proteins, some of which were serine-threonine phosphatase/kelch proteins, [21, 22, 56], and none of which were BTB/kelch proteins. Searches with the BTB domains of several human or invertebrate kelch-repeat proteins also did not identify BTB/kelch proteins in A. thaliana. BLAST genomes searches of the databases of complete or partially-sequenced eucaryotic animal and plant genomes at NCBI (Entrez/genome_tree, [57]), that included the fully-sequenced genomes of the Apicomplexium Plasmodium falciparum [58], the Microsporidium Encephalitozoon cuniculi [59], the plant Oryza sativa (rice; [60]) and the fungus Neurospora crassa [61] identified many predicted kelch-repeat-containing proteins, but no ORFs that had the BTB/kelch domain architecture. Results for selected domain architectures in five eucaryotic organisms are presented in Fig. 6. We did, however, note in Apicomplexia species, two proteins with K Tetra /kelch domain architecture (NP_705330 and EAA22466). The K tetra domain (Pfam 02214) is a distant structural relative of the BTB/POZ domain [62]. Overall, these results provide a significant indication that protein-encoding sequences for the BTB/kelch domain architecture have become expanded during the evolution of multicellular animals, compared to Apicomplexia, fungi, plants and other eucaryotes.

Prevalence of selected kelch-repeat protein domain architectures in eucaryotes. The bar charts represent the number of kelch-repeat proteins with the indicated domain architectures encoded in the proteomes of H. sapiens (Hs), D. melanogaster (Dm), C. elegans (Ce), S. pombe (Sp) and A. thaliana (At).

Discussion

Our analysis of the molecular organisation and phylogeny of kelch-repeat proteins provides a new view on the evolution of the kelch-repeat domain and the proteins that share this domain. Several features distinguish the kelch-motif and its domain superfamily from other sequence motifs that fold as β-propeller structures. First, the consensus sequence of a kelch motif differs from that of other β-propeller motifs, such as the WD motif, RCC1 motif, tachylectin-2 repeat or YWTD motif [3, 5, 7]. Secondly, the majority of the β-propeller domains that have been crystallised are seven- or eight-bladed β-propeller structures [3, 5, 7, 8]. A geometric preference for assembly of seven-bladed β-propellers over six or eight bladed-forms has been demonstrated by mathematical modelling [63] and indeed the majority of WD motif proteins, a considerably more numerous domain family in metazoa than the kelch-repeat proteins, are predicted to form seven-bladed β-propellers [7, 64]. Our comprehensive evaluation of kelch-repeat domains in the proteomes of multiple eucaryotic organisms clearly delineates a preponderance of predicted six-bladed β-propellers in the kelch-repeat superfamily. In addition, WD proteins have been identified as proteins of eucaryotic animals and plants [5, 6, 64], whereas kelch-repeats are universally represented in eucaryotes, bacteria and viruses.

The data also present new insights into the evolution of domain organisation in kelch-repeat proteins. Kelch-repeat domains are found in proteins from all forms of life, yet the diverse domain architectures of kelch-repeat proteins and the significant differences in the relative representation of domain architecture groups encoded in the genomes of animals, fungi and plants attest to considerable functional diversification and biological specialisation of the superfamily. The prevalence of the F-box/kelch domain architecture in plants has been recognised [21, 22]. We report clear evidence for the prevalence of the BTB/kelch domain architecture in the kelch-repeat proteins of metazoan animals from C. elegans to human (Fig. 6). The expansion of this subgroup appears animal-specific, because although kelch repeats are found in all eucaryotes and the BTB domain is present in fungi and animals, the combination of the BTB/kelch domain organisation was only identified in animals, where the subgroup appears to have expanded as a gene family in conjunction with multicellularity. Other domain architectures, such as F-box/kelch or discoidin domain/kelch, are present in a wider range of eucaryotic organisms, suggestive of an earlier evolutionary origin.

The other organisms in which BTB/kelch proteins have been identified are members of the animal poxvirus family. In these viruses, which are thought to have acquired these genes by horizontal transfer from animals, BTB/kelch-encoding ORFs are found with the variable long terminal regions (LTR) of the genomes which determine the species-trophism and strain-specific properties of each virus. [54]. Cowpox virus, which has the broadest host range, contains six BTB/kelch-encoding sequences, whereas in variola virus (smallpox virus), that has a single host, all the kelch/BTB sequences are disrupted by mutations that truncate the ORFs [54, 65]. Therefore, it has been suggested that the BTB/kelch proteins encoded in poxviruses could detemine the host range and/or pathogenicity of a virus [54]. Alternatively, the proteins might act to modulate host immune response to virus infection or might be necessary for in vivo host/virus interactions, for example subversion of host cell functions such as cytoskeletal organisation or formation of cell signaling protein complexes, that would affect the ability of the virus to persist within the host. The three BTB/kelch proteins of vaccina virus are not necessary for viral replication in culture and further targeted experiments are needed to establish the function of BTB/kelch proteins in cowpox and other poxviruses [66]. A greater understanding of the normal functions of animal BTB/kelch proteins could help reveal the roles of poxvirus BTB/kelch proteins.

In addition, the large numbers of BTB/kelch proteins identified in metazoan animal genomes, particularly in human, present an interesting enigma. Why do animals need so many BTB/kelch proteins? Only eight out of the 51 human BTB/kelch proteins are of known function (Table 1). Although there are multiple examples of BTB/kelch proteins that bind actin [3], multiple sequence alignment of the human BTB/kelch proteins showed that the known actin-binding kelch-repeat proteins did not belong to a specific sequence subgroup (Fig. 2A). This result is not unexpected, given the low sequence constraints for assembly of a β-propeller and the preference for a binding "supersite" on one propeller face [67]. Our studies of the two robust BTB/kelch subgroups indicate distinctions in specific secondary or tertiary structural features of these β-propellers, with regard to loop and β-propeller organisation, that could be important for the functions of these proteins. Although, for the reasons stated above, it is unlikely that the these features specify a common binding partner, we suggest that the differences in positioning of the major loops in the kelch-repeats of subgroups 1 and 2A could provide important indications of the location and characteristics of putative protein-binding sites. The studies identified general distinctions between the two subgroups (the positioning of the longest 2–3 and 4–1 loops within the domain and the mean length of 2–3 loops) and also unusual features of single repeats in specific proteins. This information could be important for the analysis of proteins within these groups, to accelerate rational design of mutational and functional studies. It would also be of obvious interest to have crystal structure information for a representative β-propeller from each BTB/kelch subgroup and for the other domain architecture groups. Interestingly, the BTB/kelch proteins of insects and C. elegans were all, with one exception, most closely-related to the subgroup 1 human BTB/kelch proteins (Tables 2 and 3, Fig. 2). Thus, subgroup 1 may represent the BTB/kelch proteins of earliest origin from which others have diversified during evolution, making these proteins particularly significant for further study. The majority of eucaryotic kelch-repeat proteins are predicted to be intracellular proteins. Many proteins in the β-propeller fold family function as enzymatic, scaffolding, or transducer components of protein complexes [5, 6, 8]. We speculate that many of the currently uncharacterised BTB/kelch-repeat proteins of animals will turn out to be components of multiprotein complexes with roles in reception of extracellular cues, cell signaling and transport, or cell organisation.

Conclusions

The kelch-repeat superfamily constitutes a distinct and evolutionarily-widespread family of β-propeller domain-containing proteins. Expansion of the family during the evolution of multicellular animals is mainly accounted for by a major expansion of the BTB/kelch domain architecture. BTB/kelch proteins constitute 72 % of the kelch-repeat superfamily of H. sapiens and form three subgroups, one of which appears the most-conserved during evolution. Distinctions in propeller blade organisation between subgroups 1 and 2, with respect to loop length and charge distribution and the positioning of major loops within the β-propeller domain were identified that could provide new direction for biochemical and functional studies of novel kelch-repeat proteins.

Methods

BLAST Database searches and identification of Domain Architectures

The whole human genome http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/seq/HsBlast.html was searched with the 46 residue consensus sequence for the Kelch motif (PRSGAGVVVVGGKIYVIGGFDGSQSLSSVEVYDPETNTWEKLPSMP; CDD543) by the basic local alignment search tools BLASTP and PSI-BLAST [67, 68] at standard parameters, with a default expectation value of 10 and reporting up to 500 protein sequences. The database was also searched with the kelch repeats from human host cell factor-1 (aa1-aa357; [30]), mouse leucine-zipper-like transcriptional regulator (aa49-aa369; [69]), rat Actinfilin (aa331-aa616; [70]), human Rag2 (aa1-aa348; [16]), human muskelin (aa 249–636; [71]), the complete sequences of all the previously-characterised kelch-repeat proteins [3] and examples of single kelch-repeats that differ in length or sequence characteristics from the kelch motif consensus (repeat 3 of mouse muskelin, repeats 3, 4, 5 of RAG-2, repeat 1 of NP_695002, repeat 4 of NP_040383, repeat 1 of NP_071324). The listings of kelch proteins in Pfam 9.0 [19] (Wellcome Trust-Sanger Institute) and SMART [20] (EMBL) domain databases were also analysed and any apparent additional human kelch-repeat proteins searched against GenBank. From these searches, we found that the species listings in Pfam and SMART did not include all the kelch-repeat proteins identified in our searches and contained multiple redundant entries including partial ORFs for the same protein. Each identified protein sequence was reciprocally searched against the non-redundant protein database of GenBank and Conserved Domain Database [72] (which includes the Pfam and SMART databases) to confirm the identification of kelch repeats and to identify additional domains. Novel hypothetical ORFs within the human genome were used to query the database of human expressed sequence tags (ESTs) to determine whether corresponding translation products could be identified. Hits that appeared ambiguous as putative incomplete open reading frames in the initial search were excluded from further analysis, but were also searched against the mouse and rat genome databases at NCBI. The same search methods were used to identify kelch-repeat proteins in the genome databases of D. melanogaster [33], A. gambiae [34], C. elegans [35], S. cerevisiae [50], S. pombe [49] and A. thaliana [55] at NCBI. A. gambiae proteins were not listed in the Pfam or SMART species trees. All these searches were carried out in the period March 18 to April 20, 2003. A second set of searches were carried out between 14th June and 22nd July, 2003. Each identified sequence from these species was used in BLAST searches of the human genome to identify the closest human homologue (ie, an ORF with significant identity to the entire protein sequence, not only to the kelch repeats). Previously unknown proteins identified in these searches were also used to query the human genome database to determine if additional human kelch-repeat proteins could be identified. Other eucaryotic genomes were searched through the BLAST Genomes interface at NCBI [57]. At the time of search, this database included complete or partial genome sequence information for 48 eucaryotic genomes (12 complete), 222 eubacterial genomes and 18 archaebacterial genomes.

Entries in the human proteome which appeared to be partial sequences included GenBank XP_054631, which was 91 % identical to the C3IP1 Kelch-protein (Accession NP_067646). Comparison of the two sequences at the nucleotide level showed that a single nucleotide deletion (ACAG TGG→ACATG G) in the XP_054631 entry generated an additional start-codon, in the equivalent position to valine100 in C3IP1. Additionally, a single mutation in XP_054631 (GTCC GACG→GTCTGA CG) generates a stopcodon and consequently a truncated open reading frame. Thus, the XP_054631 and NP_067646 entries appeared to be derived from the same gene and only NP_067646 is included in Table 1. The entry XP_209285 encoded a open reading frame of 128 amino acids, containing 3 kelch-repeats with highest sequence identity to rat actinfilin, NP_663704, length 640 amino acids [70]. Additional searches with rat actinfilin did not identify a full-length human sequence. The entry NP_689579 encoded a 263 residue polypeptide containing 2 kelch-repeats. We identified orthologues in both Mus musculus and Rattus norvegicus of 303 amino acids and 238 amino acids, respectively. Alignments of all three orthologues indicate a highly conserved segment identified in all three orthologues, a segment only present in human, and a segment only present in mouse. These discrepancies may arise from alternate predictions of intron-exon boundaries during genome annotation. All these entries were excluded from Table 1 and from the further sequence analyses at this time.

Prediction of β-propeller closure mechanisms

β-propeller closure mechanisms for the human kelch-repeat proteins were predicted by use of Jpred secondary structure prediction, to identify beta-sheet secondary structure either amino- or carboxy-terminal to the kelch motifs in each polypeptide sequence http://www.compbio.dundee.ac.uk/~www-jpred. Each sequence was also examined manually for the presence of a tryptophan residue amino-terminal to the first motif or carboxy-terminal to the last motif, as a second predictor of amino-terminal or carboxy-terminal β-propeller closure mechanisms, respectively, [3].

Multiple sequence alignment and identification of human BTB/kelch protein subgroups

All the full-length human BTB/kelch protein sequences predicted to form six-bladed propellers (38 sequences) were aligned by CLUSTALW [73] multiple sequence alignment at EMBnet http://www.ch.EMBnet.org, European Bioinformatics Institute http://www.ebi.ac.uk and at the San Diego Supercomputer Center Biology Workbench 3.2 http://workbench.sdsc.edu, with similar results. Alignments, bootstrap analysis and neighborhood-joining trees were carried out at default parameters from the full-length sequences, from the kelch-repeats alone, or from the BTB domains alone, at the Biology Workbench and are presented as neighbourhood-joining trees (rooted dendrograms prepared by reference to the unrooted trees) prepared in the Phylip Drawgram 3.5c software at Biology Workbench [74], with annotation in Adobe Illustrator. These analyses identified two major robustly-related subgroups within the kelch/BTB proteins. These groupings were substantiated by a second method, PROTPARS (Felsenstein, J. 1993. PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package) version 3.5c, distributed by the author, Department of Genetics, University of Washington, Seattle) for maximum parsimony analysis of sequence relationships, also carried out at Biology Workbench. CLUSTALW multiple sequence alignments of the kelch-repeats from the two subgroups consistently identified by CLUSTALW and PROTPARS were used to derive a 50 % identity consensus sequence for each subgroup and are presented in Boxshade 3.2. The 50 % identity consensus sequence derived from each set of six kelch motifs were re-aligned with each other to prepare a averaged single motif consensus at 50 % identity for each subgroup in CLUSTALW. These averaged consensus motifs were mapped against the tertiary structure of a kelch-repeat β-propeller blade using the structure of fungal galactose oxidase (PDB 1GOF) as a template and the Swiss-PDB viewer software http://www.expasy.org/spdbv/.

Acknowledgements

We thank Raymond Monk for assistance with checking database entries.

Abbreviations

- BLAST:

-

basic local alignment search tool

- BTB/POZ:

-

Broad-Complex, Tramtrack, and Bric-a-Brac/ Poxvirus and Zincfinger domain

- CDD:

-

conserved domain database

- EST:

-

expressed sequence tag

- ORF:

-

open reading frame, Pfam, Protein families database of alignments and HMMs

- SMART:

-

simple modular architecture research tool.

References

Xue F, Cooley L: kelch encodes a component of intercellular bridges in Drosophila egg chambers. Cell 1993, 72: 681–693.

Bork P, Doolittle R: Drosophila kelch motif is derived from a common enzyme fold. J Mol Biol 1994, 236: 1277–1282.

Adams JC, Kelso R, Cooley L: The kelch repeat superfamily : propellers of cell function. Trends Cell Biol 2000, 10: 17–24. 10.1016/S0962-8924(99)01673-6

Ito N, Phillips SEV, Yadav KDS, Knowles PF: Crystal structure of a free radical enzyme, galactose oxidase. J Mol Biol 1994, 238: 794–814. 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1335

Fulop V, Jones DT: Beta propellers : structural rigidity and functional diversity. Curr Opin Struct Biol 1999, 9: 715–721. 10.1016/S0959-440X(99)00035-4

Jawad Z, Paoli M: Novel sequences propel familiar folds. Structure 2002, 10: 447–454. 10.1016/S0969-2126(02)00750-5

Andrade MA, Perez-Iratxeta C, Ponting C: Protein repeats : structures, functions and evolution. J Struct Biol 2001, 134: 117–131. 10.1006/jsbi.2001.4392

Smith TF, Gaitatazes C, Saxena K, Neer EJ: The WD repeat : a common architecture for diverse functions. Trends Biochem Sci 1999, 24: 181–185. 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01384-5

Renault A, Nassar N, Vetter I, Becker J, Klebe C, Roth M, Wittinghofer A: The 1.7A crystal structure of the regulator of chromosome condensation (RCC1) reveals a seven-bladed propeller. Nature 1998, 392: 97–101. 10.1038/32204

Faber HR, Groom CR, Baker HM, Morgan WT, Smith A, Baker EN: 1.8A structure of the C-terminal domain of rabbit serum hemopexin. Structure 1995, 3: 551–559.

Li J, Brick P, O'Hare MC, Skarzynski T, Lloyd LF, Curry VA, Clark IM, Bigg HF, Hazleman BL, Cawston TE, Blow DM: Structure of full-length porcine synovial collagenase reveals a C-terminal domain containing a calcium-linked, four-bladed beta-propeller. Structure 1995, 3: 341–349.

Robinson DN, Cooley L: Drosophila kelch is an oligomeric ring canal actin organiser. J Cell Biol 1997, 138: 799–810. 10.1083/jcb.138.4.799

Kim IF, Mohammadi E, Huang RC: Isolation and characterization of IPP, a novel human gene encoding an actin-binding, kelch-like protein. Gene 1999, 228: 73–83. 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00006-2

Ding J, Liu JJ, Kowal AS, Nardine T, Bhattacharya P, Lee A, Yang Y: Microtubule-associated protein 1B: a neuronal binding partner for gigaxonin. J Cell Biol 2002, 158: 427–433. 10.1083/jcb.200202055

Itoh K, Wakabayashi N, Katoh Y, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Engel JD, Yamamoto M: Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain. Genes Dev 1999, 13: 76–86. 10.1101/gad.13.17.2328

Callebaut I, Mornon J-P: The V(D)J recombination activating protein RAG2 consists of a six-bladed propeller and a PHD fingerlike domain, as revealed by sequence analysis. Cell Mol Life Sci 1998, 54: 880–891. 10.1007/s000180050216

Albagli O, Dhordain P, Deweindt C, Lecocq G, Leprince D: The BTB/POZ domain: a new protein-protein interaction motif common to DNA- and actin-binding proteins. Cell Growth Differ 1995, 6: 1193–1198.

Zipper LM, Mulcahy RT: The Keap1 BTB/POZ dimerization function is required to sequester Nrf2 in cytoplasm. J Biol Chem 2002, 277: 36544–36552. 10.1074/jbc.M206530200

Bateman A, Birney E, Cerruti L, Durbin R, Etwiller L, Eddy SR, Griffiths-Jones S, Howe KL, Marshall M, Sonnhammer EL: The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res 2002, 30: 276–280. 10.1093/nar/30.1.276

Schultz J, Milpetz F, Bork P, Ponting CP: SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool : Identification of signaling domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 1998, 95: 5857–5864. 10.1073/pnas.95.11.5857

Andrade MA, Gonzalez-Guzman M, Serrano R, Rodriguez PL: A combination of the F-box-motif and kelch repeats defines a large Arabidopsis family of F-box proteins. Plant Mol Biol 2001, 46: 603–614. 10.1023/A:1010650809272

Kuroda H, Takahashi N, Shimada H, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Matsui M: Classification and expression analysis of Arabidopsis F-box-containing protein genes. Plant Cell Physiol 2002, 43: 1073–1085. 10.1093/pcp/pcf151

Baumgartner S, Hofmann K, Chiquet-Ehrismann R, Bucher P: The discoidin domain family revisited: new members from prokaryotes and a homology-based fold prediction. Protein Sci 1998, 7: 1626–1631.

Craig KL, Tyers M: The F-box: a new motif for ubiquitin dependent proteolysis in cell cycle regulation and signal transduction. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 1999, 72: 299–328. 10.1016/S0079-6107(99)00010-3

Somers DE: Clock-associated genes in Arabidopsis : a family affair. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2001, 3560: 1745–1753. 10.1098/rstb.2001.0965

De Baere I, Janssens V, van Hoof C, Waelkens E, Merlevede W, Goris J: Purification of porcine brain protein phosphatase 2A leucine carboxyl methyltransferase and cloning of the human homologue. Biochemistry 1999, 38: 16539–16547. 10.1021/bi991646a

Duke-Cohan JS, Gu J, McLaughlin DF, Xu Y, Freeman GJ, Schlossman SF: Attractin (DPPT-L) a member of the CUB family of cell adhesion and guidance proteins, is secreted by activated human T lymphocytes and modulates immune cell interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 1998, 95: 11336–11341. 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11336

Gunn TM, Miller KA, He L, Hyman RW, Davis RW, Azarani A, Schlossman SF, Duke-Cohan JS, Barsch GS: The mouse mahogany locus encodes a transmembrane form of human attractin. Nature 1999, 398: 152–156. 10.1038/18217

Nagle DL, McGrail SH, Vitale J, Woolf EA, Dussault BJ, DiRocco L, Holmgren L, Montagno J, Bork P, Huszar D, Fairchild-Huntress V, Ge P, Keilty J, Ebeling C, Baldini L, Gilchrist J, Burn P, Carlson GA, Moore KJ: The mahogany protein is a receptor involved in suppression of obesity. Nature 1999, 398: 148–152. 10.1038/18210

Wilson AC, Freiman RN, Goto H, Nishimoto T, Herr W: VP16 targets an amino-terminal domain of HCF involved in cell-cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol 1997, 17: 6139–6146.

Johnson KM, Mahajan SS, Wilson AC: Herpes simplex virus transactivator VP16 discriminates between HCF-1 and a novel family member, HCF-2. J Virol 1999, 73: 3930–3940.

Diaz E, Schimmoller F, Pfeffer SR: A novel Rab9 effector required for endosome to TGN transport. J Cell Biol 1997, 138: 283–290. 10.1083/jcb.138.2.283

Adams MD, Celnicker SE, Holt RA, Evans CA, Gocayne JD, Amanatides PG, Scherer SE, Li PW, Hoskins RA, Galle RF, George RA, Lewis SE, Richards S, Ashburner M, Henderson SN, Sutton GG, Wortman JR, Yandell MD, Zhang Q, Chen LX, Brandon RC, Rogers YH, Blazej RG, Champe M, Pfeiffer BD, Wan KH, Doyle C, Baxter EG, Helt G, Nelson CR, Gabor GL, Abril JF, Agbayani A, An HJ, Andrews-Pfannkoch C, Baldwin D, Ballew RM, Basu A, Baxendale J, Bayraktaroglu L, Beasley EM, Beeson KY, Benos PV, Berman BP, Bhandari D, Bolshakov S, Borkova D, Botchan MR, Bouck J, Brokstein P, Brottier P, Burtis KC, Busam DA, Butler H, Cadieu E, Center A, Chandra I, Cherry JM, Cawley S, Dahlke C, Davenport LB, Davies P, de Pablos B, Delcher A, Deng Z, Mays AD, Dew I, Dietz SM, Dodson K, Doup LE, Downes M, Dugan-Rocha S, Dunkov BC, Dunn P, Durbin KJ, Evangelista CC, Ferraz C, Ferriera S, Fleischmann W, Fosler C, Gabrielian AE, Garg NS, Gelbart WM, Glasser K, Glodek A, Gong F, Gorrell JH, Gu Z, Guan P, Harris M, Harris NL, Harvey D, Heiman TJ, Hernandez JR, Houck J, Hostin D, Houston KA, Howland TJ, Wei MH, Ibegwam C, Jalali M, Kalush F, Karpen GH, Ke Z, Kennison JA, Ketchum KA, Kimmel BE, Kodira CD, Kraft C, Kravitz S, Kulp D, Lai Z, Lasko P, Lei Y, Levitsky AA, Li J, Li Z, Liang Y, Lin X, Liu X, Mattei B, McIntosh TC, McLeod MP, McPherson D, Merkulov G, Milshina NV, Mobarry C, Morris J, Moshrefi A, Mount SM, Moy M, Murphy B, Murphy L, Muzny DM, Nelson DL, Nelson DR, Nelson KA, Nixon K, Nusskern DR, Pacleb JM, Palazzolo M, Pittman GS, Pan S, Pollard J, Puri V, Reese MG, Reinert K, Remington K, Saunders RD, Scheeler F, Shen H, Shue BC, Siden-Kiamos I, Simpson M, Skupski MP, Smith T, Spier E, Spradling AC, Stapleton M, Strong R, Sun E, Svirskas R, Tector C, Turner R, Venter E, Wang AH, Wang X, Wang ZY, Wassarman DA, Weinstock GM, Weissenbach J, Williams SM, Woodage T, Worley KC, Wu D, Yang S, Yao QA, Ye J, Yeh RF, Zaveri JS, Zhan M, Zhang G, Zhao Q, Zheng L, Zheng XH, Zhong FN, Zhong W, Zhou X, Zhu S, Zhu X, Smith HO, Gibbs RA, Myers EW, Rubin GM, Venter JC: The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster . Science 2000, 287: 2185–2195. 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185

Holt RA, Subramanian GM, Halpern A, Sutton GG, Charlab R, Nusskern DR, Wincker P, Clark AG, Ribeiro JM, Wides R, Salzberg SL, Loftus B, Yandell M, Majoros WH, Rusch DB, Lai Z, Kraft CL, Abril JF, Anthouard V, Arensburger P, Atkinson PW, Baden H, de Berardinis V, Baldwin D, Benes V, Biedler J, Blass C, Bolanos R, Boscus D, Barnstead M, Cai S, Center A, Chaturverdi K, Christophides GK, Chrystal MA, Clamp M, Cravchik A, Curwen V, Dana A, Delcher A, Dew I, Evans CA, Flanigan M, Grundschober-Freimoser A, Friedli L, Gu Z, Guan P, Guigo R, Hillenmeyer ME, Hladun SL, Hogan JR, Hong YS, Hoover J, Jaillon O, Ke Z, Kodira C, Kokoza E, Koutsos A, Letunic I, Levitsky A, Liang Y, Lin JJ, Lobo NF, Lopez JR, Malek JA, McIntosh TC, Meister S, Miller J, Mobarry C, Mongin E, Murphy SD, O'Brochta DA, Pfannkoch C, Qi R, Regier MA, Remington K, Shao H, Sharakhova MV, Sitter CD, Shetty J, Smith TJ, Strong R, Sun J, Thomasova D, Ton LQ, Topalis P, Tu Z, Unger MF, Walenz B, Wang A, Wang J, Wang M, Wang X, Woodford KJ, Wortman JR, Wu M, Yao A, Zdobnov EM, Zhang H, Zhao Q, Zhao S, Zhu SC, Zhimulev I, Coluzzi M, della Torre A, Roth CW, Louis C, Kalush F, Mural RJ, Myers EW, Adams MD, Smith HO, Broder S, Gardner MJ, Fraser CM, Birney E, Bork P, Brey PT, Venter JC, Weissenbach J, Kafatos FC, Collins FH, Hoffman SL: The genome sequence of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae . Science 2002, 298: 129–149. 10.1126/science.1076181

The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium: Genome Sequence of the Nematode C. elegans . Science 1998, 282: 2012–2018. 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012

Zdobnov EM, von Mering C, Letunic I, Torrents D, Suyama M, Copley RR, Christophides GK, Thomasova D, Holt RA, Subramanian GM, Mueller HM, Dimopoulos G, Law JH, Wells MA, Birney E, Charlab R, Halpern AL, Kokoza E, Kraft CL, Lai Z, Lewis S, Louis C, Barillas-Mury C, Nusskern D, Rubin GM, Salzberg SL, Sutton GG, Topalis P, Wides R, Wincker P, Yandell M, Collins FH, Ribeiro J, Gelbart WM, Kafatos FC, Bork P: Comparative genome and proteome analysis of Anopheles gambiae and Drosophila melanogaster . Science 2002, 298: 149–159. 10.1126/science.1077061

Robinson DN, Cooley L: Examination of the function of two kelch proteins generated by stop codon suppression. Development 1997, 124: 1405–1417.

Adams JC: Characterization of a Drosophila melanogaster orthologue of muskelin. Gene 2002, 297: 69–78. 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)00887-9

Izeta A, Malcomber S, O'Hare P: Primary structure and compartmentalization of Drosophila melanogaster host cell factor. Gene 2003, 305: 175–183. 10.1016/S0378-1119(03)00380-9

Ohmachi M, Sugimoto A, Iino Y, Yamamoto M: kel-1, a novel Kelch-related gene in Caenorhabditis elegans , is expressed in pharyngeal gland cells and is required for the feeding process. Genes Cells 1999, 4: 325–337. 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1999.00264.x

Varkey JP, Muhlrad PJ, Minniti AN, Do B, Ward S: The Caenorhabditis elegans spe-26 gene is necessary to form spermatids and encodes a protein similar to the actin-associated proteins kelch and scruin. Genes Dev 1995, 9: 1074–1086.

Maeda I, Kohara Y, Yamamoto M, Sugimoto A: Large-scale analysis of gene function in Caenorhabditis elegans by high-throughput RNAi. Curr Biol 2001, 11: 171–176. 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00052-5

Wysocka J, Liu Y, Kobayashi R, Herr W: Developmental and cell-cycle regulation of Caenorhabditis elegans HCF phosphorylation. Biochemistry 2001, 40: 5786–5794. 10.1021/bi010086o

Liu Y, Hengartner MO, Herr W: Selected elements of herpes simplex virus accessory factor HCF are highly conserved in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Cell Biol 1999, 19: 909–915.

Brown NR, Noble ME, Endicott JA, Garman EF, Wakatsuki S, Mitchell E, Rasmussen B, Hunt T, Johnson LN: The crystal structure of cyclin A. Structure 1995, 3: 1235–1247.

Freemont PS: The RING finger. A novel protein sequence motif related to the zinc finger. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1993, 684: 174–192.

Mata J, Nurse P: tea1 and the microtubular cytoskeleton are important for generating global spatial order within the fission yeast cell. Cell 1997, 89: 939–949.

Philips J, Herskowitz I: Identification of Kel1p, a kelch domain-containing protein involved in cell fusion and morphology in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . J Cell Biol 1998, 143: 375–389. 10.1083/jcb.143.2.375

Wood V, Gwilliam R, Rajandream MA, Lyne M, Lyne R, Stewart A, Sgouros J, Peat N, Hayles J, Baker S, Basham D, Bowman S, Brooks K, Brown D, Brown S, Chillingworth T, Churcher C, Collins M, Connor R, Cronin A, Davis P, Feltwell T, Fraser A, Gentles S, Goble A, Hamlin N, Harris D, Hidalgo J, Hodgson G, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Howarth S, Huckle EJ, Hunt S, Jagels K, James K, Jones L, Jones M, Leather S, McDonald S, McLean J, Mooney P, Moule S, Mungall K, Murphy L, Niblett D, Odell C, Oliver K, O'Neil S, Pearson D, Quail MA, Rabbinowitsch E, Rutherford K, Rutter S, Saunders D, Seeger K, Sharp S, Skelton J, Simmonds M, Squares R, Squares S, Stevens K, Taylor K, Taylor RG, Tivey A, Walsh S, Warren T, Whitehead S, Woodward J, Volckaert G, Aert R, Robben J, Grymonprez B, Weltjens I, Vanstreels E, Rieger M, Schafer M, Muller-Auer S, Gabel C, Fuchs M, Dusterhoft A, Fritzc C, Holzer E, Moestl D, Hilbert H, Borzym K, Langer I, Beck A, Lehrach H, Reinhardt R, Pohl TM, Eger P, Zimmermann W, Wedler H, Wambutt R, Purnelle B, Goffeau A, Cadieu E, Dreano S, Gloux S, Lelaure V, Mottier S, Galibert F, Aves SJ, Xiang Z, Hunt C, Moore K, Hurst SM, Lucas M, Rochet M, Gaillardin C, Tallada VA, Garzon A, Thode G, Daga RR, Cruzado L, Jimenez J, Sanchez M, del Rey F, Benito J, Dominguez A, Revuelta JL, Moreno S, Armstrong J, Forsburg SL, Cerutti L, Lowe T, McCombie WR, Paulsen I, Potashkin J, Shpakovski GV, Ussery D, Barrell BG, Nurse P, Cerrutti L: The genome sequence of Schizosaccharomyces pombe . Nature 2002, 415: 871–880. 10.1038/nature724

Goffeau A, Barrell BG, Bussey H, Davis RW, Dujon B, Feldmann H, Galibert F, Hoheisel JD, Jacq C, Johnston M, Louis EJ, Mewes HW, Murakami Y, Philippsen P, Tettelin H, Oliver SG: Life with 6000 genes. Science 1996, 274: 546–549. 10.1126/science.274.5287.546

Fukui Y, Miyake S, Satoh M, Yamamoto M: Characterisation of the S. pombe ral2 gene implicated in activation of the ras1 gene product. Mol Cell Biol 1989, 9: 5617–5622.

Harashima T, Heitman J: The Ga protein Gpa2 controls yeast differentiation by interacting with kelch repeat proteins that mimic Gb subunits. Mol Cell 2002, 10: 163–173.

Batlle M, Lu A, Green AL, Xue Y, Hirsch JP: Krh1p and Krh2p act downstream of the Gpa2p Ga subunit to negatively regulate haploid invasive growth. J Cell Sci 2003, 116: 701–711. 10.1242/jcs.00266

Shchelkunov S, Totmenin A, Kolosova I: Species-specific differences in organisation of orthopoxvirus kelch-like proteins. Virus Genes 2002, 24: 157–162. 10.1023/A:1014524717271

Arabidopsis genome initiative: Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana . Nature 2000, 408: 796–815. 10.1038/35048692

Kutuzov MA, Andreeva AV: Protein ser/thr phosphatases with kelch-like domains. Cell Signal 2002, 14: 745–750. 10.1016/S0898-6568(02)00018-9

Cummings L, Riley L, Black L, Souvorov A, Resenchuk S, Dondoshansky I, Tatusova T: Genomic BLAST: custom-defined virtual databases for complete and unfinished genomes. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2002, 216: 133–138. 10.1016/S0378-1097(02)00955-2

Gardner MJ, Hall N, Fung E, White O, Berriman M, Hyman RW, Carlton JM, Pain A, Nelson KE, Bowman S: Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum . Nature 2002, 419: 498–511. 10.1038/nature01097

Katinka MD, Duprat S, Cornillot E, Metenier G, Thomarat F, Prensier G, Barbe V, Peyretaillade E, Brottier P, Wincker P: Genome sequence and gene compaction of the eukaryote parasite Encephalitozoon cuniculi . Nature 2001, 414: 450–453. 10.1038/35106579

Yu J, Hu S, Wang J, Wong GK, Li S, Liu B, Deng Y, Dai L, Zhou Y, Zhang X, Cao M, Liu J, Sun J, Tang J, Chen Y, Huang X, Lin W, Ye C, Tong W, Cong L, Geng J, Han Y, Li L, Li W, Hu G, Huang X, Li W, Li J, Liu Z, Li L, Liu J, Qi Q, Liu J, Li L, Li T, Wang X, Lu H, Wu T, Zhu M, Ni P, Han H, Dong W, Ren X, Feng X, Cui P, Li X, Wang H, Xu X, Zhai W, Xu Z, Zhang J, He S, Zhang J, Xu J, Zhang K, Zheng X, Dong J, Zeng W, Tao L, Ye J, Tan J, Ren X, Chen X, He J, Liu D, Tian W, Tian C, Xia H, Bao Q, Li G, Gao H, Cao T, Wang J, Zhao W, Li P, Chen W, Wang X, Zhang Y, Hu J, Wang J, Liu S, Yang J, Zhang G, Xiong Y, Li Z, Mao L, Zhou C, Zhu Z, Chen R, Hao B, Zheng W, Chen S, Guo W, Li G, Liu S, Tao M, Wang J, Zhu L, Yuan L, Yang H: A Draft Sequence of the Rice Genome ( Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica). Science 2002, 296: 79–84. 10.1126/science.1068037

Galagan JE, Calvo SE, Borkovich KA, Selker EU, Read ND, Jaffe D, FitzHugh W, Ma LJ, Smirnov S, Purcell S, Rehman B, Elkins T, Engels R, Wang S, Nielsen CB, Butler J, Endrizzi M, Qui D, Ianakiev P, Bell-Pedersen D, Nelson MA, Werner-Washburne M, Selitrennikoff CP, Kinsey JA, Braun EL, Zelter A, Schulte U, Kothe GO, Jedd G, Mewes W, Staben C, Marcotte E, Greenberg D, Roy A, Foley K, Naylor J, Stange-Thomann N, Barrett R, Gnerre S, Kamal M, Kamvysselis M, Mauceli E, Bielke C, Rudd S, Frishman D, Krystofova S, Rasmussen C, Metzenberg RL, Perkins DD, Kroken S, Cogoni C, Macino G, Catcheside D, Li W, Pratt RJ, Osmani SA, DeSouza CP, Glass L, Orbach MJ, Berglund JA, Voelker R, Yarden O, Plamann M, Seiler S, Dunlap J, Radford A, Aramayo R, Natvig DO, Alex LA, Mannhaupt G, Ebbole DJ, Freitag M, Paulsen I, Sachs MS, Lander ES, Nusbaum C, Birren B: The genome sequence of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa . Nature 2003, 422: 859–868. 10.1038/nature01554

Bixby KA, Nanao MH, Shen NV, Kreusch A, Bellamy H, Pfaffinger PJ, Choe S: Zn2+-binding and molecular determinants of tetramerization in voltage-gated K+ channels. Nat Struct Biol 1999, 6: 38–43. 10.1038/4911

Murzin AG: Structural principles for the propellor assembly of beta-sheets : the preference for seven-fold symmetry. Proteins 1992, 14: 191–201.

Yu L, Gaitatazes C, Neer E, Smith TF: Thirty-plus families from a single motif. Protein Sci 2000, 9: 2470–2476.

Shchelkunov SN, Safronov N, Totmenin AV, Petrov NA, Ryazankina OI, Gutorov VV, Kotwal GJ: The genomic sequence analysis of the left and right species-specific terminal region of a cowpox virus strain reveals unique sequences and a cluster of intact ORFs for immunology and host range proteins. Virology 1998, 243: 432–460. 10.1006/viro.1998.9039

Perkus ME, Goebel SJ, Davis SW, Johnson GP, Norton EK, Paoletti E: Deletion of 55 open reading frames from the termini of vaccinia virus. Virology 1991, 180: 406–410.

Russell RB, Sasieni PD, Sternberg MJE: Supersites within superfolds. Binding site similarity in the absence of homology. J Mol Biol 282: 903–918.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ: Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 1990, 215: 403–410. 10.1006/jmbi.1990.9999

Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ: Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 1997, 25: 3389–3402. 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389

Kurahashi H, Akagi K, Inazawa J, Ohta T, Niikawa N, Kayatani F, Sano T, Okada S, Nishisho I: Isolation and characterization of a novel gene deleted in DiGeorge syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 1995, 4: 541–549.

Chen Y, Derin R, Petralia RS, Li M: Actinfilin, a brain-specific actin-binding protein in postsynaptic density. J Biol Chem 2002, 277: 30495–30501. 10.1074/jbc.M202076200

Adams JC, Zhang L: Localisation of mouse and human muskelin (MKLN1) genes by FISH and physical mapping. Cytogenet and Cell Genet 1999, 86: 19–21.

Marchler-Bauer A, Panchenko AR, Shoemaker BA, Thiessen PA, Geer LY, Bryant SH: CDD : a database of conserved domain alignments with links to domain three-dimensional structure. Nucleic Acid Res 2002, 30: 281–283. 10.1093/nar/30.1.281

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ: CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 1994, 22: 4673–4680.

Felsenstein J: PHYLIP – Phylogeny Inference Package (Version 3.2). Cladistics 1989, 5: 164–166.

Seki N, Ohira M, Nagase T, Ishikawa K, Miyajima N, Nakajima D, Nomura N, Ohara O: Characterization of cDNA clones in size-fractionated cDNA libraries from human brain. DNA Res 1997, 4: 345–349.

Taylor A, Obholz K, Linden G, Sadiev S, Klaus S, Carlson KD: DNA sequence and muscle-specific expression of human sarcosin transcripts. Mol Cell Biochem 1998, 183: 105–112. 10.1023/A:1006824331819

Spence HJ, Johnston I, Ewart K, Buchanan SJ, Fitzgerald U, Ozanne BW: Krp1, a novel kelch related protein that is involved in pseudopod elongation in transformed cells. Oncogene 2000, 19: 1266–1276. 10.1038/sj.onc.1203433

Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, Derge JG, Klausner RD, Collins FS, Wagner L, Shenmen CM, Schuler GD, Altschul SF, Zeeberg B, Buetow KH, Schaefer CF, Bhat NK, Hopkins RF, Jordan H, Moore T, Max SI, Wang J, Hsieh F, Diatchenko L, Marusina K, Farmer AA, Rubin GM, Hong L, Stapleton M, Soares MB, Bonaldo MF, Casavant TL, Scheetz TE, Brownstein MJ, Usdin TB, Toshiyuki S, Carninci P, Prange C, Raha SS, Loquellano NA, Peters GJ, Abramson RD, Mullahy SJ, Bosak SA, McEwan PJ, McKernan KJ, Malek JA, Gunaratne PH, Richards S, Worley KC, Hale S, Garcia AM, Gay LJ, Hulyk SW, Villalon DK, Muzny DM, Sodergren EJ, Lu X, Gibbs RA, Fahey J, Helton E, Ketteman M, Madan A, Rodrigues S, Sanchez A, Whiting M, Madan A, Young AC, Shevchenko Y, Bouffard GG, Blakesley RW, Touchman JW, Green ED, Dickson MC, Rodriguez AC, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, Myers RM, Butterfield YS, Krzywinski MI, Skalska U, Smailus DE, Schnerch A, Schein JE, Jones SJ, Marra MA, Mammalian Gene Collection Program Team: Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2002, 99: 16899–16903. 10.1073/pnas.242603899

Nagase T, Nakayama M, Nakajima D, Kikuno R, Ohara O: Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. XX. The complete sequences of 100 new cDNA clones from brain which code for large proteins in vitro. DNA Res 2001, 8: 85–95.

Chang-Yeh A, Jabs EW, Li X, Dracopoli NC, Huang RC: The IPP gene is assigned to human chromosome 1p32–1p22. Genomics 1993, 15: 239–241. 10.1006/geno.1993.1048

Wolff T, O'Neill RE, Palese P: NS1-Binding protein (NS1-BP): a novel human protein that interacts with the influenza A virus nonstructural NS1 protein is relocalized in the nuclei of infected cells. J Virol 1998, 72: 7170–7180.

Sasagawa K, Matsudo Y, Kang M, Fujimura L, Iitsuka Y, Okada S, Ochiai T, Tokuhisa T, Hatano M: Identification of Nd1, a novel murine kelch family protein, involved in stabilization of actin filaments. J Biol Chem 2002, 277: 44140–44146. 10.1074/jbc.M202596200

Nagase T, Kikuno R, Ohara O: Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. XXI. The complete sequences of 60 new cDNA clones from brain which code for large proteins. DNA Res 2001, 8: 179–187.

Hattori A, Okumura K, Nagase T, Kikuno R, Hirosawa M, Ohara O: Characterization of long cDNA clones from human adult spleen. DNA Res 2000, 7: 357–366.

Gupta-Rossi N, Storck S, Griebel PJ, Reynaud CA, Weill JC, Dahan A: Specific over-expression of deltex and a new Kelch-like protein in human germinal center B cells. Mol Immunol 2003, 39: 791–799. 10.1016/S0161-5890(03)00002-6

Wang S, Zhou Z, Ying K, Tang R, Huang Y, Wu C, Xie Y, Mao Y: Cloning and characterization of KLHL5, a novel human gene encoding a kelch-related protein with a BTB domain. Biochem Genet 2001, 39: 227–238. 10.1023/A:1010203114697

Soltysik-Espanola M, Rogers RA, Jiang S, Kim TA, Gaedigk R, White RA, Avraham H, Avraham S: Characterization of Mayven, a novel actin-binding protein predominantly expressed in brain. Mol Biol Cell 1999, 10: 2361–2375.

Nagase T, Kikuno R, Ishikawa KI, Hirosawa M, Ohara O: Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. XVI. The complete sequences of 150 new cDNA clones from brain which code for large proteins in vitro. DNA Res 2000, 7: 65–73.

Hernandez MC, Andres-Barquin PJ, Holt I, Israel MA: Cloning of human ENC-1 and evaluation of its expression and regulation in nervous system tumors. Exp Cell Res 1998, 242: 470–477. 10.1006/excr.1998.4109

Kim TA, Lim J, Ota S, Raja S, Rogers R, Rivnay B, Avraham H, Avraham S: NRP/B, a novel nuclear matrix protein, associates with p110(RB) and is involved in neuronal differentiation. J Cell Biol 1998, 141: 553–566. 10.1083/jcb.141.3.553

Hirosawa M, Nagase T, Ishikawa K, Kikuno R, Nomura N, Ohara O: Characterization of cDNA clones selected by the GeneMark analysis from size-fractionated cDNA libraries from human brain. DNA Res 1999, 6: 329–336.

Lai F, Orelli BJ, Till BG, Godley LA, Fernald AA, Pamintuan L, Le Beau MM: Molecular characterization of KLHL3, a human homologue of the Drosophila kelch gene. Genomics 2000, 66: 65–75. 10.1006/geno.2000.6181

Nomura N, Ohara O: Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. IX. The complete sequences of 100 new cDNA clones from brain which can code for large proteins in vitro. DNA Res 1998, 5: 31–39.

von Bulow M, Heid H, Hess H, Franke WW: Molecular nature of calicin, a major basic protein of the mammalian sperm head cytoskeleton. Exp Cell Res 1995, 219: 407–413. 10.1006/excr.1995.1246

Wiemann S, Weil B, Wellenreuther R, Gassenhuber J, Glassl S, Ansorge W, Bocher M, Blocker H, Bauersachs S, Blum H, Lauber J, Dusterhoft A, Beyer A, Kohrer K, Strack N, Mewes HW, Ottenwalder B, Obermaier B, Tampe J, Heubner D, Wambutt R, Korn B, Klein M, Poustka A: Toward a catalog of human genes and proteins: sequencing and analysis of 500 novel complete protein coding human cDNAs. Genome Res 2001, 11: 422–435. 10.1101/gr.GR1547R

Nemes JP, Benzow KA, Moseley ML, Ranum LP, Koob MD: The SCA8 transcript is an antisense RNA to a brain-specific transcript encoding a novel actin-binding protein (KLHL1). Hum Mol Genet 2000, 9: 1543–1551. 10.1093/hmg/9.10.1543

Bomont P, Cavalier L, Blondeau F, Ben Hamida C, Belal S, Tazir M, Demir E, Topaloglu H, Korinthenberg R, Tuysuz B, Landrieu P, Hentati F, Koenig M: The gene encoding gigaxonin, a new member of the cytoskeletal BTB/kelch repeat family, is mutated in giant axonal neuropathy. Nat Genet 2000, 26: 370–374. 10.1038/81701

Itoh K, Wakabayashi N, Katoh Y, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Engel JD, Yamamoto M: Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain. Genes Dev 1999, 13: 76–86. 10.1101/gad.13.17.2328

Velichkova M, Guttman J, Warren C, Eng L, Kline K, Vogl AW, Hasson T: A human homologue of Drosophila kelch associates with myosin-VIIa in specialized adhesion junctions. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 2002, 51: 147–164. 10.1002/cm.10025

Braybrook C, Warry G, Howell G, Arnason A, Bjornsson A, Moore GE, Ross MT, Stanier P: Identification and characterization of KLHL4, a novel human homologue of the Drosophila Kelch gene that maps within the X-linked cleft palate and Ankyloglossia (CPX) critical region. Genomics 2001, 72: 128–136. 10.1006/geno.2000.6478

Nagase T, Nakayama M, Nakajima D, Kikuno R, Ohara O: Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. XX. The complete sequences of 100 new cDNA clones from brain which code for large proteins in vitro. DNA Res 2001, 8: 85–95.

Nakayama M, Nakajima D, Nagase T, Nomura N, Seki N, Ohara O: Identification of high-molecular-weight proteins with multiple EGF-like motifs by motif-trap screening. Genomics 1998, 51: 27–34. 10.1006/geno.1998.5341

Ohinata Y, Sutou S, Mitsui Y: A novel testis-specific RAG2-like protein, Peas: its expression in pachytene spermatocyte cytoplasm and meiotic chromatin. FEBS Lett 2003, 537: 1–5. 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00036-X

Zhou HJ, Wong CM, Chen JH, Qiang BQ, Yuan JG, Jin DY: Inhibition of LZIP-mediated transcription through direct interaction with a novel host cell factor-like protein. J Biol Chem 2001, 276: 28933–28938. 10.1074/jbc.M103893200

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

SP carried out genome surveys, assigned domain organisations, identified the three subgroups of BTB/kelch proteins and prepared tables and figures. JCA carried out additional database searches and sequence analysis, searched other eucaryotic and Arabidopsis genomes, prepared tables and figures and wrote the paper.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Prag, S., Adams, J.C. Molecular phylogeny of the kelch-repeat superfamily reveals an expansion of BTB/kelch proteins in animals. BMC Bioinformatics 4, 42 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-4-42

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-4-42